Abstract

Behavior analysts in human service agencies are commonly expected to train support staff as one of their job duties. Traditional staff training is usually didactic in nature and generally has not proven particularly effective. We describe an alternative, evidence-based approach for training performance skills to human service staff. The description includes a specific means of conducting a behavioral skills training session with a group of staff followed by on-the-job training requirements. A brief case demonstration then illustrates application of the training approach and its apparent effectiveness for training staff in two distinct skill sets: use of most-to-least prompting within teaching procedures and use of manual signs. Practical issues associated with applying evidence-based behavioral training are presented with a focus on providing training that is effective, efficient, and acceptable to staff trainees.

Keywords: behavioral skills training, evidence-based practices, most-to-least prompting, staff training

Behavior analysts often share the job duty of training support staff in human service agencies to implement intervention plans for challenging behavior (Macurik, O'Kane, Malanga, & Reid, 2008) or teaching strategies (Catania, Almeida, Liu-Constant, & Reed, 2009; Rosales, Stone, & Rehfeldt, 2009) with consumers. In addition, staff are often trained in general principles and practices of behavior analysis (Lerman, Tetreault, Hovanetz, Strobel, & Garro, 2008). Disseminating information about effective practices among caregivers in this regard has become a professionally expected responsibility of behavior analysts (Lerman, 2009).

The importance of training human service staff was recognized early in the history of behavior analysis as it became clear that making a large-scale impact on consumers required effective training of support staff (Frazier, 1972). Behavioral researchers then began investigating staff training procedures (see Miller & Lewin, 1980; Reid & Whitman, 1983, for reviews of the early research on staff training). Researchers have continued to examine the effects of staff training strategies to allow for more effective and efficient use of behavioral procedures with individuals with disabilities. Despite this existing research, many staff in human service agencies often do not acquire the skills that the procedures are intended to train (Casey & McWilliam, 2011; Clark, Cushing, & Kennedy, 2004; Sturmey, 1998). Hence, if behavior analysts are to successfully fulfill their staff-training responsibilities, additional guidance on best-practice implementation of staff training strategies is warranted.

The purpose of this paper is to describe an evidence-based protocol for training human service staff. Although this training technology has been discussed from several perspectives (e.g., Reid, O'Kane, & Macurik, 2011), the focus here is on describing the basic components of the training protocol for behavior analyst practitioners. Suggestions are also provided for effectively implementing the protocol based on our training experience. Following a summary of the evidence-based training protocol, a brief case demonstration is presented to illustrate its application. Practical issues often related to the overall success of staff training are then offered for consideration.

Before describing the evidence-based training protocol, it should be noted that the focus of this training model is on training performance skills. Staff are trained to perform work duties that they previously could not perform prior to training. The model stands in contrast to approaches that focus primarily on enhancing knowledge or verbal skills, which would allow them to answer questions about the target skills. Though knowledge enhancement is clearly an important function of certain training endeavors, the goal of this protocol is improved performance (Parsons & Reid, 2012). The distinction between training performance versus verbal skills is important because of the different outcomes expected as a function of the training process and because different training procedures are required. Early behavioral research demonstrated that staff training programs relying on verbal-skill strategies (e.g., lectures, presentation of written and visual material) are effective for enhancing targeted knowledge, but often are ineffective for teaching trainees to perform newly targeted job skills (Gardner, 1972). Thus, programs that rely heavily on verbal-skill training approaches typically prove ineffective in creating a meaningful impact on the job performance of human service staff (Alavosius & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1990; Petscher & Bailey, 2006; Phillips, 1998).

A Protocol for Evidence-Based Staff Training

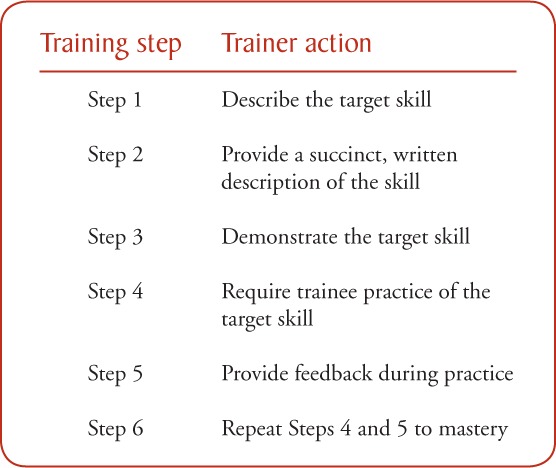

Evidence-based staff training consists of performance- and competency-based strategies (Reid et al., 2003). The phrase performance-based refers to what the trainer and trainees do (i.e., actively perform the specific responses being trained) during the training. The phrase competency-based refers to the practice of continuing training until trainees competently demonstrate the skills of concern (i.e., meet established mastery criteria). Specifically, the training is data-based; observational data are obtained to document that trainees demonstrate the target skills at established proficiency criteria. More recently, this approach to staff training (i.e., instructions, modeling, practice, and feedback until mastery is achieved) has been referred to as behavioral skills training or BST (Miles & Wilder, 2009; Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004). The procedures and literature described here are generally consistent with the research and procedures described as BST, though the specific procedural steps may vary slightly. A basic protocol for conducting a BST session is presented in Table 1. The protocol consists of six steps, each of which is described in subsequent sections. This protocol is designed for training staff using a group format; however, the same basic steps can be used when training an individual staff member though some variations may be needed for individual implementation such as with behavioral coaching (Rodriguez, Loman, & Horner, 2009) and when all training occurs in-vivo or on the job (Miles & Wilder, 2009).

Table 1.

Behavioral Skills Training Protocol for Conducting a Training Session With a Group of Staff

Step 1: Describe the Target Skill

The first training step involves the trainer providing a rationale for the importance of the skill being trained and a description of the behaviors required to perform the skill (Willner, Braukmann, Kirigin, Fixsen, Phillips, & Wolf, 1977). This step is generally referred to as instructions in the BST model. To adequately complete this step, trainers must behaviorally define the target skill using a tool such as a performance checklist of necessary staff actions (Lattimore, Stephens, Favell, & Risley, 1984).

Step 2: Provide a Succinct Written Description of the Target Skill

Following a vocal description of the target skill, trainers should provide each trainee with a written description of the target behaviors that constitute the skill. The performance checklist referred to in Step 1 often serves this function. The trainer may also need to provide a written summary of precisely what staff should do in different situations (Macurik et al., 2008), such as when being trained to implement a plan to reduce challenging behavior. The description should be succinct and focus on exactly what needs to be done to perform the target skill.

Many trainers fail to provide a succinct, written description of the target skill (Reid, Parsons, & Green, 2012, Chapter 4). Instead of providing staff trainees with a written summary, they are referred to a lengthier document (e.g., a formal behavior plan) available in a central location. Our experience suggests that a number of staff typically will not access the plan to review the information when needed. Documents such as plans for challenging behavior frequently contain much more information than what staff need to implement the plan (e.g., background consumer information, assessment processes used to develop the plan), though the information is important for other purposes.

Step 3: Demonstrate the Target Skill

Once trainees have heard and read a description of the actions to perform the target skill, the trainer should demonstrate how to perform the skill. This step, referred to as modeling in BST, can usually be readily accomplished by using a role-play process (Adams, Tallon, & Rimell, 1980), and particularly when two trainers are present. One trainer plays the role of a staff member and the other trainer plays the role of a consumer (if the target skill involves interacting with a consumer). It is critical that role-play demonstrations be well-scripted and rehearsed prior to the training session to ensure an accurate and fluent demonstration of all key components of the target skill. If a second trainer is not available, a trainee can assist in the demonstration. In the latter case, the trainer must provide detailed instructions to the trainee to ensure the trainee knows exactly what should be done during the demonstration. We have also found it helpful for trainer(s) to stop or “freeze” at certain points and describe what is being done and why to help trainees attend to key actions being demonstrated. Alternatively, video models have been effectively incorporated into BST as the demonstration component for teaching staff various skills such as conducting discrete-trial instruction (Catania et al., 2009; Sarakoff & Sturmey, 2004) and use of picture communication systems (Rosales et al., 2009).

Step 4: Require Trainee Practice of the Target Skill

After demonstration of the target skill, trainees rehearse performing the skill in a role play similar to the trainer demonstration (Adams et al., 1980). Instructions are given to organize trainees such that one can play the role of the consumer (again, if relevant) and one can demonstrate the target skill while other trainees observe. All trainees must practice performing the target skill.

The trainee practice step, referred to as rehearsal in BST, is frequently omitted during staff training (Reid et al., 2012, Chapter 4). In many staff training programs, only vocal and written descriptions of the target skill are provided, perhaps supplemented with a demonstration. This omission likely occurs because the practice component requires significant time investment for each trainee to practice the skill. However, practicing the skill is a critical feature for the success of BST and should be required of each trainee to produce effective performance (Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010; Rosales et al., 2009).

Step 5: Provide Performance Feedback During Practice

The fifth step of the training protocol is for trainers to provide feedback to the trainees as they practice performing the target skill. Trainers should circulate among the trainees to observe their performance and provide individualized supportive and corrective feedback (Parsons & Reid, 1995). Supportive feedback entails describing to the trainee exactly what s/he performed correctly and corrective feedback involves specifying what was not performed correctly. Corrective feedback also involves providing instruction about exactly how to perform any aspects of the target skill performed incorrectly in order to facilitate proficient future performance of the skill. Generally we recommend providing feedback following completion of a given role play in contrast to interrupting an ongoing role-play activity to provide feedback.

Observing trainees and providing feedback to each trainee requires time and effort on the part of trainers. This is another reason that it is often beneficial to have two trainers present, and especially if the number of trainees exceeds four or five. Providing individualized feedback is as critical to the training process as the trainee practice component, and must involve each trainee.

Step 6: Repeat Steps 4 and 5 to Mastery

The final step in a BST session is to repeat Steps 4 and 5 until each trainee performs the target skill proficiently (Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010). Trainers should establish a mastery criterion, such as trainees performing 100% of the target steps correctly (Miles & Wilder, 2009) or perhaps a lower percentage but with identification of certain critical steps that must be performed at 100% proficiency (Neef, Trachtenberg, Loeb, & Sterner, 1991). This final step represents the essence of the competency part of BST. A staff training session should not be considered complete until each trainee performs the target skill competently.

On-The-Job Training

The group training protocol is designed to train staff at one time in a situation that differs from the daily work situation. The format is commonly used in human service settings where behavior analysts practice. However, because the training involves a simulated situation (e.g., role plays, no consumers present), the overall training process is not complete. The session must be followed by on-the-job training.

On-the-job, or in-vivo, training increases the likelihood that performance of the target skill acquired during the training session generalizes to the usual work situation (Clark et al., 2004; Smith, Parker, Taubman, & Lovaas, 1992). On-the-job training involves trainers observing each trainee applying the target skill in the regular work environment and providing supportive and corrective feedback as described in Step 5 of the training protocol. Observations and feedback should continue until each trainee performs the target skill proficiently during the typical work routine.

The on-the-job component is another aspect of the training process that can involve a substantial time investment by trainers because they must go to each trainee's worksite for observation and feedback. In this regard, we have found that the amount of time trainers will have to spend at trainee work sites will be minimized if each trainee has previously demonstrated competence during role plays in the training session; proficiency in demonstrating a target skill on the job often parallels the level of proficiency demonstrated during previous role plays.

The on-the-job training component completes the training process. However, it should also be emphasized that although completion of training is often a necessary step to promote proficient staff performance on the job, it is rarely a sufficient step (Reid et al., 2012, Chapter 4). Newly acquired job skills must be addressed from a performance management perspective (Austin, 2000) to ensure they maintain, and particularly with continued presentation of feedback by supervisors and related personnel. Describing effective on-the-job performance management is beyond the scope of this paper; however, a number of resources describe evidence-based approaches to managing daily work performance of staff (e.g., Austin; Daniels, 1994; Reid et al., 2012).

Case Demonstration of Evidence-Based Staff Training

To illustrate how BST can be applied to train staff in a group format in a human service setting, the following case demonstration is presented. The demonstration involved training two sets of skills deemed important by the staff supervisor.

Method

Setting and participants.

The demonstration occurred during ongoing services at an education program for adults with severe disabilities. The primary locations were classrooms in which instructional services and paid work (e.g., contract work, retail manufacturing) occurred. Seven teachers and one teacher's assistant served as participants; six of these participants were women. Participant ages ranged from 30 to 53 years (M = 45 years) and their experience ranged from 1 to 30 years (M = 14). Each teacher was responsible for services in a given classroom and the teacher's assistant worked in one of the classrooms. Each teacher was licensed in special education. Four teachers had a bachelor's degree and three had a master's degree.

Behavior definitions and observation systems.

The skill sets targeted for training were selected by the supervisor of the program (experimenter) based on her view of relevant skill targets. The first skill set pertained to using a most-to-least (ML) assistive prompting strategy (Libby, Weiss, Bancroft, & Ahearn, 2008) while teaching consumers. All participants had previously mastered using a least-to-most assistive (LM) prompting strategy (Parsons & Reid, 1999), which was the most common prompting approach used in the adult education program. The supervisor's intent was to expand the participants' teaching skills by training them to also be able to use the alternative, ML prompting strategy. The second targeted skill involved the use of manual signing in interactions with certain adult students. Only seven participants were involved in this training due to a medical leave. Each participant interacted, or potentially could interact, with a student who responded to and/or used manual signs for communication. However, the participants had not received formal training in manual signing for at least several years, if at all.

The ML prompting protocol involved five teaching components based on previous research on LM prompting (Parsons & Reid, 1999). First, correct order was defined as teaching the steps of a student program in the exact sequence specified in the program task analysis. Second, correct reinforcement was defined as providing a consequence after the last correct step in a program and not providing the same consequence for any incorrectly performed step by the student. Reinforcement could be provided for correct student completion of any step but must be provided for the last correctly completed step. Third, correct error correction was defined as the teacher interrupting a student's error and providing increased assistance sufficient such that the student then correctly completed the step. Correct prompting (modified from prior research to target ML) involved two components. The first component, full physical guidance on the first teaching trial, was defined as the teacher physically guiding the student through all steps of the task analysis. The second component, less assistive prompts on subsequent trials, was defined as the teacher beginning at least one step on the target trial by guiding the student through the step, stopping the guidance at a point earlier than on the previous trial for that step, and not providing more assistance on any step for the target trial relative to the preceding trial. Hence, there were five overall components constituting correct teaching: the three components pertaining to order, reinforcement, error correction, and the two prompting components.

The five teaching components were observed for each participant's teaching session and each component was scored as correct or incorrect for each instructional trial conducted during the session. To be scored as correct, a component had to be performed correctly for each step of the task analysis with which it was used. If a necessary component was omitted (omission error) or a component was performed incorrectly (commission error), then that component was scored as incorrect. Following a teaching session, the percentages of the five teaching components performed correctly were averaged to obtain a percentage correct score for the teaching session. Due to the specific focus on ML prompting, the percentages of the two prompting components performed correctly were also calculated and reported separately. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted during 75% of all teaching sessions, involving each participant and experimental condition. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements on occurrence of a correct teaching component by the number of disagreements plus agreements, multiplied by 100. Agreement averaged 95% (range, 86% to 100%).

The skill set for manual signing involved 35 signs. The signs were selected by the participants' supervisor based on her familiarity with the signs that were used by or with the adult students and that would likely be applicable within ongoing activities. The signs pertained to items (e.g., coffee, key, soda), actions (e.g., come, stop, work), descriptors (e.g., hot, good, slow), and private events (e.g., hungry, pain, thirsty). A correct production of each sign required three components (Fitzgerald, Reid, Schepis, Faw, Welty, & Pyfer, 1984) including (a) movements of the fingers and hand(s), (b) shapes of the fingers and hand(s), and (c) location of the fingers and hand(s) in respect to the body. These components were derived from the pictures and descriptions presented in Sign Language Made Simple (Lewis & Henderson, 1997).

Signs were assessed on a trial-by-trial basis with an observer recording a correct production only if the sign met all three of the adherence criteria. Incorrect production was scored if an error occurred on any one component or if the participant verbally indicated s/he did not know the sign. Interobserver agreement checks were conducted on a sign-by-sign basis during all trials on 36% of assessment sessions, for each participant and condition. Agreement averaged 89% (range, 67% to 100%).

Baseline procedures.

Baseline sessions occurred individually with each participant. The experimenter explained that, as part of the program's professional development activities, participants would be assessed and trained to use an ML prompting strategy and a sample of manual signs. For the ML prompting baseline sessions, the experimenter further explained the participant would be asked to train three skills during role play with an experimenter playing the part of a student. The three skills were wiping the mouth with a napkin (three task-analyzed steps), activating a CD player (four steps), and placing paper in a paper shredder (three steps). The participant was instructed to teach the “student” all task-analyzed steps of a respective skill using three trials with ML prompting and to fade the prompting across successive trials. No feedback was provided to the participant.

During the baseline, the experimenter playing the role of the student followed a set script. The script specified that the “student” should: (1) require full physical guidance for all task-analyzed steps on the first trial of a given skill, (2) require full physical guidance to initiate a step during the second trial and then complete that step independently and subsequently require full physical guidance to complete the other steps on the second trial, and (3) complete the first step independently on the third trial and then make an error on a subsequent step and require partial physical guidance on the remaining steps.

Baseline sessions for assessing manual signing skills involved the following procedures. First, the experimenter informed the participant that one word would be spoken at a time and the participant should make the sign that represented the word. Second, the experimenter said one word and waited for the participant to make a sign or indicate that s/he did not know how to make the sign. Third, this process was repeated for the remaining 34 signs. The presentation order of the words for signs was altered across sessions according to a set format.

Training and post-training procedures.

Training on ML prompting and signing involved the steps of the evidence-based protocol described earlier and occurred in a group format with all participants simultaneously. Each training session lasted a maximum of one hour to accommodate staff 's typical daily planning time and minimize disruption of delivery of consumer services. Three training sessions were conducted for ML prompting across different days, and three sessions were conducted for signing, also across different days. Two trainers (experimenters) conducted the training sessions.

The first training session for ML prompting was initiated by a trainer explaining the rationale for the training, followed by a description of the five components of teaching. A succinct, written handout of the definitions was also provided (see http://www.abainternational.org/Journals/bap_supplements.asp to download these definitions). Any questions posed by the trainees were answered and included reference to the written description. Next, a trainer demonstrated teaching a task-analyzed skill in a role play (i.e., the other trainer in the role of “student”) using the script described previously. The target skill (i.e., decorating cookies with sprinkles) was different than the three skills assessed in the baseline assessment. Following each demonstration trial, the trainer paused to explain what she did and answer participant questions. Subsequently, participants each practiced teaching a trainer using the same target skill (again, decorating a cookie) and received feedback while the other trainees observed. Next, participants practiced teaching each other in a role play. The two trainers circulated among the participants during the role-play practice to observe, score, and provide feedback. The observation, trainee practice, and trainer feedback continued until each trainee demonstrated 100% correct teaching proficiency one time with the target student skill. The second training session involved the same process (i.e., brief vocal description, demonstration, and participant practice with feedback) with two new student skills (i.e., removing trash from a table and placing it into a trash can, playing the game of “cornhole” that involved throwing a bean bag through a hole in a board). The third training session involved continued practice with the student skills covered in the first two sessions until each participant correctly performed 100% of the five teaching components.

Manual sign training began with 15 signs during the first training session. The trainer described the importance of signing with students who used signs for communication. Next, the trainer described how to make each of five signs according to the three criteria noted earlier while the participants followed along with a handout that described making the signs and provided a picture of each sign (see Lewis & Henderson, 1997, for illustrations). The trainer then demonstrated each sign. Subsequently, the participants were divided into small groups. Participants were then instructed to have one participant name the five signs for the others to produce and provide feedback to each other using the handout as a guide, and then to alternate the role of naming the signs. The trainers circulated among the groups to observe, score each sign production, and provide feedback. The trainees continued practicing until each trainee correctly produced 100% of the target signs. Five more signs were then demonstrated by a trainer and subsequently combined with the initial group of five signs for trainee practice and feedback. This process was then repeated for five more signs.

During the second training session, the 15 signs introduced in the first session were described and demonstrated again, along with trainee practice. Next, the process used in the first training session was followed with two more groups of 5 signs. The third training session replicated the second, along with the introduction of the remaining 10 signs in two groups of five. The final component of the third training session involved the participants practicing all 35 signs and receiving feedback from each other as well as a trainer until each participant correctly demonstrated each sign.

Post-training assessments occurred within one week following the last training session and involved conducting individual assessments with participants in the same manner as during baseline. Additionally, at the end of the assessment praise was provided for correct performance and if needed, corrective feedback for performance errors.

On-the-job assessments.

On-the-job assessments were conducted to evaluate whether competent performance established in the training context occurred when trainees used the skills during their routine job duties. For ML prompting, participants were informed that the supervisor would be coming to their classroom to observe their use of ML prompting while teaching a student. Participants were asked to select the student and a skill to teach that differed from the staff training and role-play skills (examples of skills taught in the classrooms included putting materials away in a cabinet, folding washcloths, and rinsing dishes). Upon arrival, the supervisor asked to see the task analysis of the skill and observed the participant's use of ML prompting during teaching. One on-the-job session was conducted for each participant during baseline and one was conducted during post-training. The post-training session occurred four days after the last simulated post-training assessment and included feedback following the session. Interobserver agreement checks occurred during 81% of all on-the-job sessions, across all participants and both experimental conditions. Agreement for occurrence of correct teaching components averaged 97% (range, 82% to 100%).

For the on-the-job sessions with signing, the supervisor informed the participants that she would be coming to their classroom to observe them using a relevant sample of the signs trained. On-the-job sessions only occurred during the post-training condition after the participants had been trained in the manual signs (M = 18 days following the last post-training session, range 14 to 24 days). No baseline session was conducted for signing because the risk of creating an uncomfortable experience for the staff was considered high while the likelihood of correct production of untrained signs was considered very low. Participants were asked to select signs that were relevant for the observed situation and to demonstrate at least five signs (M = 6.1 signs, range of 5 to 8). Interobserver agreement checks occurred during 43% of the on-the-job observations. There were no disagreements between observers.

Experimental design.

The experimental design was a multiple baseline design across behaviors (i.e., ML prompting and signing).

Acceptability measures.

Participants anonymously completed an acceptability survey after the post-training, on-the-job assessments. Participants placed the completed and unsigned form in a folder in a secretary's office to ensure anonymity. Three questions were posed with a 7-point Likert scale response option, with “4” representing the neutral point. The questions sampled how useful the training was (“1” = extremely nonuseful, “7” = extremely useful), how practical the training was in terms of amount of time and work to participate (“1” = extremely impractical, “7” extremely practical) and how enjoyable the training was (“1” = extremely not enjoyable, “7” = extremely enjoyable). A fourth question asked if the participant would recommend the training to his/her colleagues and used a “yes” or “no” response option.

Results

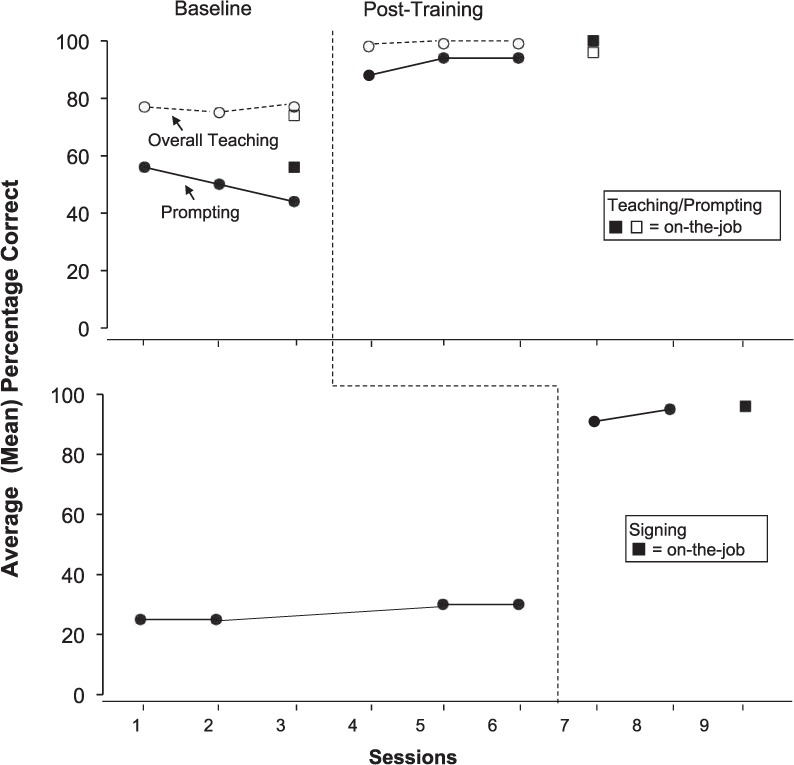

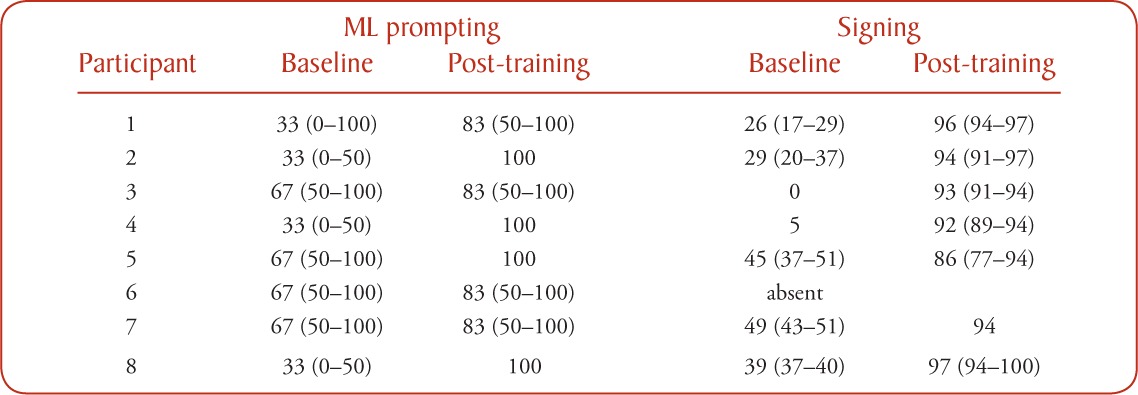

The results are presented in graphic form (Figure 1) for the entire group and in tabular form (Table 2) for the individual participants. The group-based training program appeared effective with both ML prompting and signing skills. The top panel illustrates the average percentage of all five teaching components implemented correctly (open symbols) and the average percentage for the two ML prompting components depicted as an additional data path (closed symbols). During baseline, the average percentage of overall teaching components was relatively high for the group of participants, averaging 76% (range, 75% to 77%). However, the average for the prompting components was considerably lower (M = 50%, range 44% to 56%). During post-training, averages for both skill sets increased, with overall teaching averaging 99% (range, 98% to 99%) and ML prompting 92% (range, 88% to 94%). Similar increases occurred during the on-the-job assessments, with overall teaching increasing from an average of 74% during baseline to 96% in post-training, and ML prompting increasing from a baseline average of 56% to 100% in post-training. As indicated in Table 2, the performance of individual participants corresponded to the group averages depicted in Figure 1 in that all eight participants improved their prompting performances from baseline to post-training.

Figure 1.

Mean percentage correct overall teaching components (open symbols) and most-to-least prompting (closed symbols) (top panel) and signing (bottom panel) for all participants for each assessment session during each experimental condition.

Table 2.

Average Percentage (and Range) of Target Skills Performed Correctly by Individual Participants for Each Experimental Condition

The bottom panel of Figure 1 indicates that the average percentage of correctly produced signs increased from baseline (M = 28%, range 25% to 30%) to post-training (M = 93%, range 91% to 95%). The on-the-job assessment of a sample of relevant signs indicated the participants correctly produced 96% of the assessed signs. As with ML prompting correct signs increased from baseline to post-training for all participants (Table 2).

Participants reported both applications of the training process to be acceptable. For the ML prompting training and the sign training, the average rating for each of the Likert-scale questions was between “6” (very) and “7” (extremely) regarding how useful the training was, how practical the training was, and how enjoyable the training was for the participants. No rating was below “5” (mostly) for any participant for any question. All eight participants indicated they would recommend both the ML prompting and sign training to their colleagues.

General Discussion

Results of the case demonstration appear to support the effectiveness of the training protocol. All participants increased their correct ML prompting and signing skills following training and all displayed proficient use of the newly acquired skills on the job. From a practical perspective, the training did not involve disruptions in consumer services and reportedly was well received by all participants. In considering these results, it should also be noted that due to the case demonstration nature of the evaluation, the amount of evaluative data collected was less than what typically occurs with a more rigorous research process. Hence, the results should be considered with a degree of qualification.

As with any intervention or training, there are practical considerations warranting attention when using this training protocol in human service settings. For discussion purposes, these considerations can be grouped into three categories: effectiveness, efficiency, and acceptability. The degree to which staff training programs effectively establish target skills, minimize the requirements for staff time, and are acceptable to the recipients is generally considered critical to the overall success and continuation of staff training programs (Daniels, 1994; Parsons & Reid, 1999; Phillips, 1998).

Ensuring Effectiveness of Staff Training Programs

As indicated previously, typical staff training endeavors in many human service agencies rely on vocal presentations, perhaps supplemented with written handouts and some modeling. These training programs have been criticized due to demonstrated ineffectiveness for establishing the targeted performance skills (Casey & McWilliam, 2011; Clark et al., 2004; Sturmey, 1998). The evidence-based protocol described here represents an alternative approach that applies the critical components of BST (i.e., instructions, modeling, rehearsal, feedback) to staff training with demonstrated effectiveness.

Though practitioners such as behavior analysts may be skilled at interacting with consumers and implementing behavioral protocols, those same practitioners may not be well-versed in conducting staff training using behavior analytic approaches such as that described here. Practitioners must become skilled in employing effective behavioral strategies for training staff, otherwise training is not likely to effectively equip staff to apply the behavioral procedures of concern (McGimsey, Greene, & Lutzker, 1995; Reid & Parsons, 1995).

Maximizing Time Efficiency of Training

Probably the most significant practical consideration with implementing this type of performance- and competency-based training is the amount of time required for trainers and trainees. Implementing all steps of the training protocol requires more time than traditional training approaches that rely heavily on lectures and related verbal-training processes with no performance criteria. The total time necessary to implement the protocol is increased because of the repeated trainee practice with feedback. This increased time investment is a likely explanation for the continued use of verbal-based training strategies in human service agencies, along with lack of familiarity with the BST alternative (Reid, 2004). Nonetheless, it seems counterproductive to opt for more efficient training processes in lieu of less efficient strategies when only the latter are likely to result in improved performance on the job. Additionally, providing ineffective training ultimately involves further time investment to correct or improve inadequate performance on the job.

In light of practical concerns over the amount of time to conduct BST, efforts must continue to focus on increasing the time efficiency of using this training protocol. Training time with the on-the-job component can be reduced by ensuring trainee skill mastery before terminating a group training session. Incorporating visual media such as videos within the training protocol may also increase efficiency as the demonstrations might occur more quickly, illustrate identical and accurate procedures across trainers, and remain available outside of typical work hours when live trainers are not available. For example, Macurik et al. (2008) prepared a DVD that provided the description of the target skills and demonstrations for implementing treatment plans for consumers with challenging behavior. Staff trainees viewed the DVD when their work schedule permitted. The remainder of the training (i.e., trainee practice, feedback) occurred on the job. Macurik et al. found that the use of the DVD required less trainer time and was as effective as the usual process of conducting a group training session (followed by on-the-job training). However, the time to prepare a training DVD must also be considered and is probably only warranted for procedures that will need to be taught to many staff in order to obtain a reasonable return on the time investment.

Increasing investigative attention is being directed to visual media for staff training purposes, with a number of successful outcomes reported (Catania et al., 2009; Collins, Higbee, & Salzberg, 2009; Moore & Fisher, 2007). However, there have also been reports of inconsistent effectiveness of training approaches relying solely on visual media (e.g., Neef et al., 1991; Nielsen, Sigurdsson, & Austin, 2009). The primary concern in this regard is difficulty with the practice-with-feedback component of BST when using visual media exclusively (Reid et al., 2011), although more interactive media formats may address this concern (Frieder, Peterson, Woodward, Crane, & Garner, 2009). At this point, some caution seems warranted when relying solely on visual media for training purposes. However, it seems that as long as the on-the-job component is still incorporated within the overall training process to ensure trainee competence during the regular work routine, it would not matter if the initial steps of the training protocol were provided through visual media or by a trainer in a live format (e.g., Macurik et al., 2008).

A consideration related to training efficiency is the difficulty of removing trainees from their direct work with agency consumers to attend training sessions. Time to conduct training sessions that involve disruption to consumer services is a noted concern of agency administrators (Test, Flowers, Hewitt, & Solow, 2004). This issue can be addressed in some cases by conducting training during relatively brief, 1 hr maximum segments as illustrated in the case demonstration. Often it is easier to schedule training time in short sessions without causing disruptions to consumer services (e.g., during teacher planning time, immediately following consumer departure for the day) compared to traditional half-day or day-long blocks of time (Parsons & Reid, 2012).

Promoting Staff Acceptance of Training

The long-term survival of staff training programs can be affected by how acceptable the activities are to participating staff (Wolf, Kirigin, Fixsen, Blasé, & Braukmann, 1995). In short, if staff express their discontent with certain agency activities, the activities have an increased likelihood of discontinuation even if those activities have demonstrated effectiveness. In regard to the training protocol discussed here, results of investigations have generally indicated a high degree of staff acceptance of this approach to training (see Reid & Parsons, 2000, for a summary). It has not been experimentally demonstrated why this approach to staff training has generally been associated with such high staff acceptance. However, several reasons seem plausible and might be investigated in future studies. One reason is the performance-based competency requirement. Staff may find training programs more acceptable when they acquire skills that can be immediately used on the job to the benefit of their consumers relative to training that required time and effort without them becoming confident in their ability to immediately implement the new skills. Second, the extensive use of supportive feedback (i.e., descriptive praise) during trainee practice and on-the-job performance may increase acceptance (Daniels, 1994). Finally, active participation in trainee role plays may enhance staff acceptance relative to traditional trainings, which often include long periods of sitting and time listening to a lecture (Reid et al., 2012, Chapter 4).

In considering reports of staff acceptance of BST-based training programs, it should also be noted that research in this area has received some criticism due to its heavy reliance on acceptability surveys (Parsons & Reid, 2012). Staff responses on a survey conducted by their employer is important (Wolf et al., 1995), but may not be a valid indicator of the acceptability of a training program. To illustrate, survey responses do not always correspond with other behavioral measures of acceptance such as choosing to continue participating in a program when given an option (Reid & Parsons, 1995; van den Pol, Reid, & Fuqua, 1983). Continued research is warranted to more carefully evaluate staff acceptance of training programs.

Summary

The importance of relying on evidence-based practices in the provision of supports and services for individuals with disabilities is becoming well-accepted (Detrich, Keyworth, & States, 2008). It seems counterintuitive that support staff would be expected to become skilled in applying such practices when they receive training in ways that are not evidence-based in nature. This paper describes an approach to training performance skills that has an established evidence-base and could help behavior analysts in successfully training relevant work skills to human service staff. Although continued research is warranted to better refine the training technology, and particularly in regard to its efficiency, the technology seems sufficiently well-developed to represent an improved training approach relative to what has historically occurred in many human service agencies.

Footnotes

Action Editor: Linda LeBlanc

References

- Adams G. L., Tallon R. J., Rimell P. A comparison of lecture versus role-playing in the training of the use of positive reinforcement. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1980;2:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Alavosius M. P., Sulzer-Azaroff B. Acquisition and maintenance of health-care routines as a function of feedback density. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:151–162. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J. Performance analysis and performance diagnostics. In: Austin J., Carr J. E., editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 321–349. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Casey A. M., McWilliam R. A. The impact of checklist-based training on teachers' use of the zone defense schedule. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:397–401. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania C. M., Almeida D., Liu-Constant B., Reed F. D. D. Video modeling to train staff to implement discretetrial instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:387–392. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark N. M., Cushing L. S., Kennedy C. H. An intensive onsite technical assistance model to promote inclusive educational practices for students with disabilities in middle school and high school. Research & Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities. 2004;29:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Collins S., Higbee T. S., Salzberg C. L. The effects of video modeling on staff implementation of a problem-solving intervention with adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:849–854. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels A. C. Bringing out the best in people: How to apply the astonishing power of positive reinforcement. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Detrich R., Keyworth R., States J., editors. Advances in evidence-based education: Volume 1, a roadmap to evidence-based education. Oakland, CA: The Wing Institute; 2008. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J. R., Reid D. H., Schepis M. M., Faw G. D., Welty P. A., Pyfer L. M. A rapid training procedure for teaching manual sign language skills to multidisciplinary institutional staff. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1984;5:451–469. doi: 10.1016/s0270-3092(84)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier T. W. Training institutional staff in behavior modification principles and techniques. In: Ruben R. D., Fensterheim H., Henderson J. D., Ullmann L. P., editors. Advances in behavior therapy: Proceedings of the fourth conference of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 171–178. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Frieder J. E., Peterson S. M., Woodward J., Crane J., Garner M. Teleconsultation in school settings: Linking classroom teachers and behavior analysts through web-based technology. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009;2:32–39. doi: 10.1007/BF03391746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J. M. Teaching behavior modification to nonprofessionals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1972;5:517–521. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore J., Stephens T. E., Favell J. E., Risley T. R. Increasing direct care staff compliance to individualized physical therapy body positioning prescriptions: prescriptive checklists. Mental Retardation. 1984;22:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C. An introduction to the Volume 2, Number 2 of Behavior Analysis in Practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009;2:2–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03391742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C., Tetreault A., Hovanetz A., Strobel M., Garro J. Further evaluation of a brief, intensive teacher-training model. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:243–248. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K., Henderson R. Sign language made simple: A complete introduction to American Sign Language. New York: Broadway Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Libby M. E., Weiss J. S., Bancroft S., Ahearn W. H. A comparison of most-to-least and least-to-most prompting on the acquisition of solitary play skills. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1:37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03391719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macurik K. M., O'Kane N. P., Malanga P., Reid D. H. Video training of support staff in intervention plans for challenging behavior: Comparison with live training. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- McGimsey J. F., Greene B. F., Lutzker J. R. Competence in aspects of behavioral treatment and consultation: Implications for service delivery and graduate training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:301–315. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles N. I., Wilder D. A. The effects of behavioral skills training on caregiver implementation of guided compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:405–410. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R., Lewin L. M. Training and management of the psychiatric aide: A critical review. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1980;2:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. W., Fisher W. W. The effects of videotape modeling on staff acquisition of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:197–202. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.24-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N. A., Trachtenberg S., Loeb J., Sterner K. Video-based training of respite care providers: An interactional analysis of presentation format. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:473–486. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen D., Sigurdsson S. O., Austin J. Preventing back injuries in hospital settings: The effects of video modeling on safe patient lifting by nurses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:551–561. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro-Bruzzi D., Sturmey P. The effects of behavioral skills training on mand training by staff and unprompted vocal mands by children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:757–761. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B., Reid D. H. Training residential supervisors to provide feedback for maintaining staff teaching skills with people who have severe disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:317–322. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B., Reid D. H. Training basic teaching skills to paraeducators of students with severe disabilities: A one-day program. Teaching Exceptional Children. 1999;31:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(96)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B., Reid D. H. Reading groups: A practical means of enhancing professional knowledge among human service practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;4:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03391784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petscher E. S., Bailey J. S. Effects of training, prompting, and self-monitoring on staff behavior in a classroom for students with disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:215–226. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.02-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. F. Applications and contributions of organizational behavior management in schools and day treatment settings. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1998;18:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H. Training and supervising direct support personnel to carry out behavioral procedures. In: Matson J. L., Laud R. B., Matson M. L., editors. Behavior modification for persons with developmental disabilities: Treatments and supports. Kingston, NY: National Association for the Dually Diagnosed; 2004. pp. 73–99. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., O'Kane N. P., Macurik K. M. Staff training and management. In: Fisher W. W., Piazza C. C., Roane H. S., editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 281–294. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Parsons M. B. Comparing choice and questionnaire measures of the acceptability of a staff training procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:95–96. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Parsons M. B. Organizational behavior management in human service settings. In: Austin J., Carr J. E., editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 275–294. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Parsons M. B., Green C. W. The supervisor's guidebook: Evidence-based strategies for promoting work quality and enjoyment among human service staff. Morganton, NC: Habilitative Management Consultants; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Rotholz D. A., Parsons M. B., Morris L., Braswell B. A., Green C. W., Schell R. M. Training human service supervisors in aspects of positive behavior support: Evaluation of a state-wide, performance-based program. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2003;5:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Whitman T. L. Behavioral staff management in institutions: A critical review of effectiveness and acceptability. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities. 1983;3:131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez B. J., Loman S. L., Horner R. H. A preliminary analysis of the effects of coaching feedback on teacher implementation fidelity of First Step to Success. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009;2:11–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03391744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales R., Stone K., Rehfeldt R. A. The effects of behavioral skills training on implementation of the Picture Exchange Communication system. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:541–549. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarokoff R. A., Sturmey P. The effects of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:535–538. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T., Parker T., Taubman M., Lovaas O. I. Transfer of staff training from workshops to group homes: A failure to generalize across settings. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1992;13:57–71. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(92)90040-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. History and contribution of Organizational Behavior Management to services for persons with developmental disabilities. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1998;18:7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Test D. W., Flowers C., Hewitt A., Solow J. Training needs of direct support staff. Mental Retardation. 2004;42:327–337. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<327:TNODSS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol R. A., Reid D. H., Fuqua R. W. Peer training of safety-related skills to institutional staff: Benefits for trainers and trainees. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1983;16:139–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1983.16-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner A. G., Braukmann C. J., Kirigin K. A., Fixsen D. L., Phillips E. L., Wolf M. M. The training and validation of youth-preferred social behaviors of child-care personnel. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10:219–230. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. M., Kirigin K. A., Fixsen D. L., Blasé K. A., Braukmann C. J. The Teaching-Family Model: A case study in data-based program development and refinement (and dragon wrestling) Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1995;15:11–68. [Google Scholar]