Abstract

Dispositional optimism has been shown to beneficially influence various experimental and clinical pain experiences. One possibility that may account for decreased pain sensitivity among individuals who report greater dispositional optimism is less use of maladaptive coping strategies like pain catastrophizing, a negative cognitive/affective response to pain. An association between dispositional optimism and conditioned pain modulation (CPM), a measure of endogenous pain inhibition, has previously been reported. However, it remains to be determined whether dispositional optimism is also associated with temporal summation (TS), a measure of endogenous pain facilitation. The current study examined whether pain catastrophizing mediated the association between dispositional optimism and TS among 140 older, community-dwelling adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Individuals completed measures of dispositional optimism and pain catastrophizing. TS was then assessed using a tailored heat pain stimulus on the forearm. Greater dispositional optimism was significantly related to lower levels of pain catastrophizing and TS. Bootstrapped confidence intervals revealed that less pain catastrophizing was a significant mediator of the relation between greater dispositional optimism and diminished TS. These findings support the primary role of personality characteristics such as dispositional optimism in the modulation of pain outcomes by abatement of endogenous pain facilitation and less use of catastrophizing.

Keywords: Optimism, Catastrophizing, Pain Facilitation, Temporal Summation, Osteoarthritis

Introduction

A growing literature supports the health promoting effects of positive personality traits and emotions.20, 42, 46, 51 Over the past decade, researchers have begun to examine the important role of positive personality traits and emotions in explaining individual differences in the experience of acute and chronic pain.22, 34, 35, 67 In particular, dispositional optimism, described as a generalized expectancy of positive outcomes, has been linked with lower reports of clinical pain and less pain-related interference as well as less severe pain elicited in laboratory settings.9, 27, 30, 39 It has been shown that greater dispositional optimism is associated with higher levels of positive daily mood and fewer pain-related activity limitations in a sample of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.60 Likewise, studies of psychophysical pain testing have shown that higher levels of dispositional optimism are related to decreased pain severity and distress as well as greater placebo analgesia.23, 24

It may be that dispositional optimism influences pain responses by altering endogenous pain processing. Conditioned pain modulation (CPM), a measure of central pain inhibition15, 28, 29 and temporal summation (TS) of pain, a measure of central pain facilitation,54, 55, 57 are methods frequently incorporated into studies of endogenous pain processing. We recently reported that healthy young adults with higher levels of dispositional optimism demonstrated greater CPM.27 This suggests that dispositional optimism may attenuate pain severity by engaging endogenous pain inhibition. However, to further test this possibility, it was suggested that future studies examine other endogenous pain processes such as TS. TS results in the perception of increased pain despite constant or even reduced peripheral afferent input and is considered a perceptual manifestation of enhanced central excitability.57

Hood and colleagues30 have reported that pain catastrophizing, an exaggerated negative response to actual or anticipated pain,58, 59 mediated the association between dispositional optimism and reports of cold pressor pain severity. More specifically, greater dispositional optimism was associated with lower levels of pain catastrophizing, which, in turn, was associated with lower pain severity. Moreover, pain catastrophizing has also been shown to be related to endogenous pain processing, such that pain catastrophizing was predictive of lower pain inhibitory28 and greater pain facilitatory16, 44 processes in the laboratory. Taken together, it appears that pain catastrophizing may be a viable factor linking dispositional optimism with endogenous pain processes, yet this also remains to be tested. The current study will expand upon the work of Hood and colleagues by examining whether pain catastrophizing also mediates the relationship between dispositional optimism and TS.

The vast majority of studies that have examined the associations between dispositional optimism and pain responses,23, 24, 27, 30 as well as those studies that examined the associations between pain catastrophizing and endogenous pain processing,16, 28, 44 all used young, healthy volunteers. It is unclear whether the findings reported by these studies generalize to populations of older adult with persistent or recurrent pain conditions. If future research reveals similar patterns of associations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, and endogenous pain processing in older samples of adults with chronic pain, it would be important for validating the clinical relevance of these psychosocial constructs.

The goal of the current study was to test the associations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, and endogenous pain facilitation (i.e., TS) in a sample of older, community-dwelling adults with symptomatic osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. We tested the following hypotheses: 1) Dispositional optimism is significantly and inversely related to pain catastrophizing and TS. 2) Pain catastrophizing is significantly and positively associated with TS. 3) Pain catastrophizing mediates the association between dispositional optimism and TS. 4) Although not the primary criterion measure in the current study, it was also hypothesized that clinical OA pain severity is significantly related to greater dispositional optimism and lower levels of pain catastrophizing.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The current study is part of a larger ongoing project that aims to enhance the understanding of racial/ethnic differences in pain and limitations among individuals with knee OA (Understanding Pain and Limitations in Osteoarthritic Disease, UPLOAD). The UPLOAD study is a multi-site investigation that recruits participants at the University of Florida and the University of Alabama-Birmingham. The individuals described in the current sub-study were recruited at both study sites between January, 2010 and April, 2012. The measures and procedures described below are limited to those involved in the current study. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Florida and University of Alabama-Birmingham Institutional Review Boards. All participants provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation. A portion of this study has previously been presented in abstract form at the 31st annual meeting of the American Pain Society in May, 2012.26

Participants were 140 older community-dwelling adults recruited via posted fliers, radio and print media advertisements, orthopedic clinic recruitment, and word-of-mouth referral. Criteria for inclusion into the study were as follows: 1) between 45 and 85 years of age; 2) unilateral or bilateral symptomatic knee OA based upon American College of Rheumatology criteria;1 and, 3) availability to complete the two-session protocol. Individuals were excluded from participation if they met any of the following criteria: 1) prosthetic knee replacement or other clinically significant surgery to the affected knee; 2) uncontrolled hypertension, heart failure, or history of acute myocardial infarction; 3) peripheral neuropathy; 4) systemic rheumatic disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and fibromyalgia; 5) chronic daily opioid use; 6) cognitive impairment (Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) score ≤ 22); 7) excessive anxiety regarding protocol procedures (e.g., refusal to complete controlled noxious stimulation procedures); and, 8) hospitalization within the preceding year for psychiatric illness. The 140 participants in the current study represent the entire sample of adults with knee OA, who met inclusion criteria and were enrolled into the UPLOAD study as of April, 2012. Of these 140 participants, 52% self-identified as African American, while the remaining 48% self-identified as non-Hispanic white.

Procedures

Health Assessment Session (HAS)

Prior to the HAS, individuals completed all study questionnaires described below. The following demographic and health data were obtained during the HAS: self-reported sex, age, and racial identity, as well as a health history that included information pertaining to whether individuals had any mental or physical health disorders that required hospitalization in the past year. At the time of the HAS, the index of cognitive capacity (MMSE) was administered. The MMSE was used to identify any individuals with diminished attention or concentration skills that might interfere with their responses to psychophysical testing or expose them to unexpectedly high levels of noxious stimulation. Additionally, all individuals underwent a bilateral knee joint evaluation by an experienced examiner (i.e., the study rheumatologist or study nurse practitioner). Individuals’ diagnosis of osteoarthritis was confirmed by the study rheumatologist using the American College of Rheumatology criteria for symptomatic knee OA.1

Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) Session

Approximately four weeks following the HAS, individuals completed the QST session. For the 48 hours preceding their QST session, individuals were instructed to refrain from using all PRN (as needed) analgesic medications. None of the individuals in the current study reported analgesic use within the 48 hours preceding QST. For the QST session, all individuals underwent a series of controlled thermal stimulation procedures to assess TS of heat pain. TS of heat pain was assessed using a Medoc Pathway Neurosensory Analyzer (Medoc, Ltd., Ramat Yishai, Israel) with a 30 X 30 mm thermode. The intensity of the thermal stimulus (measured in degrees Centigrade) used for assessing TS across study participants was individually tailored according to subjective reports of a “moderate” pain level. The procedure for individually tailoring the heat pain stimulus was to deliver separate trials of TS with increasing thermal stimulus intensities and then determine which thermal intensity produced a moderate pain rating of ~50 (range: 40–60) on a “0–100” numeric rating scale such that 0 = no pain and 100 = the most intense pain imaginable.19. Individuals listened to recorded instructions describing how to use the 0–100 numerical pain rating scale and verbally rated their pain intensity. Tailoring the stimulus intensity for the quantitative assessment of TS has previously been shown to be effective for minimizing “ceiling effects”, which can act to confound the estimable variance in TS.14, 29

For the purpose of tailoring, all individuals underwent three separate trials of the TS procedure in ascending order using thermal stimulus intensities of 44°C, 46°C, and 48°C as target temperatures with 32°C as the inter-pulse temperature. It should be noted that some individuals were subjected to an additional 50°C stimulus only if that participant did not report pain intensity of ≥ 50 in response to the lower stimulus intensities. For each TS procedure, sequences of 5 consecutive heat pulses of < 1 second duration were delivered with inter-pulse intervals of 2.5 seconds. To minimize inconsistency in heat pain assessment due to differential anatomical locations, TS was tested on the left volar forearm of all individuals as previously described.14, 19 The position of the thermode was altered slightly between temperatures (though it remained on the volar forearm).The inter-trial interval (i.e., time between each testing temperature) was 30 seconds.

For each TS procedure, individuals were informed that the procedure would be discontinued prior to completion of the 5 pulses if a rating of 100 was given, or if they wished to discontinue the task and subsequently said, “Stop”. The temperature of the thermal stimulus for which the mean pain rating across the five pulses was ~50; range: 40–60 (i.e., a “moderate” pain level) on the 0 to 100 scale was selected as the tailored stimulus for the assessment of TS that was included as the primary dependent variable in this study. Individuals were then provided with a 20 minute rest period, following which two additional TS trials were completed at individuals’ volar forearm using the tailored thermal stimulus; these trials were subsequently included for data analysis purposes and are referred to as Trial 1 and Trial 2 in the Results section.

Measures

Temporal Summation (TS) of Heat Pain

Traditional indices derived from the assessment of repeated heat pain stimulation reported in the literature include the use of the first pain rating,54 mean pain ratings,16, 65 the final pain rating,18 the maximum pain rating,57 and the maximum pain rating minus the first pain rating,15 and It is important to note that these indices of repeated heat pain stimulation likely reflect different aspects of heat pain perception such as hyperalgesia or TS, and as a result, are not interchangeable. It can be argued that differences in first pain ratings54 and mean pain ratings16, 65 are perhaps more reflective of heat hyperalgesia, while the maximum pain rating minus the first pain rating may be thought of more as an indicator of TS.15 However, there currently appears to be no consensus regarding which indices are the most appropriate measures for hyperalgesia and TS, respectively. In this study, for which TS was the primary criterion measure, TS indices were obtained by subtracting the first pain rating from the maximum pain rating, as this reflected the Δ change score for the greatest amount of TS obtained for the two tailored TS trials.15

Ethnicity/Race

Individuals provided self-report regarding their Hispanic ethnicity and their racial background using response options consistent with the 2000 U.S. census survey. Individuals who identified their racial background as non-Hispanic and either African American or white were specifically recruited in the current study.

Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)

The LOT-R48 assesses generalized positive outcome expectancies and contains 6 self-report items (plus 4 filler items), each rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). To calculate dispositional optimism scores, the 3 negatively worded items (e.g., I hardly ever expect things to go my way) were reversed scored and summated together with the 3 positively worded items (e.g., I am always optimistic about my future) to create a summary optimism score. Substantial research supports the reliability and validity of the LOT-R instrument.49 The internal consistency (i.e., Cronbach’s α) for the LOT-R in the current study was .70.

Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ)

The CSQ45 is used to measure patients’ use of pain coping strategies. There are seven subscales consisting of six cognitive strategies and one behavioral strategy. Participants use a 7-point scale to rate how often they use each strategy to cope with pain from 0 = never do that to 6 = always do that (scores range from 0–6). Only the six items from the pain catastrophizing subscale were included in the current study (e.g., It is terrible and I feel it is never going to get any better; I feel I can’t stand it anymore). The reliability and validity of the CSQ subscales have previously been shown to be acceptable.32, 45 Cronbach’s α for the CSQ-SF catastrophizing subscale in the current study was .91. Rather than complete a large number of separate and more comprehensive questionnaires (e.g., Pain Catastrophizing Scale58), the CSQ was used to assess a range of pain coping strategies, while minimizing the assessment burden of participants.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D is a 20-item self-report tool that measures symptoms of depression in the past week including depressed mood, guilt/worthlessness, helplessness/hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite and sleep disturbance.43 The CES-D has previously been used in research involving psychiatric and non-psychiatric samples, as well as clinical samples with medical illness.10 The total score ranges from 0 to 60, and this single total score was used in the current study as an estimate of the degree of individuals’ depressive symptomatology. The validity and internal consistency of the CES-D in the general population has been reported to be acceptable.5 Cronbach’s α for the CES-D in the current study was .80.

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index of Osteoarthritis (WOMAC)

The WOMAC was used to assess individuals’ reports of osteoarthritic pain.6 The WOMAC is frequently used in research to assess individuals’ retrospective self-report of knee and hip osteoarthritis symptoms. The subscales of the WOMAC measure pain, stiffness, and physical function. The pain subscale of the WOMAC (WOMAC-pain) was used for the current study’s purposes as a general indicator of osteoarthritic pain severity during the 48 hours preceding evaluation. The WOMAC pain subscale asks individuals about how much pain they experience during five different daily scenarios such as going up and down stairs and while lying in bed. Pain is rated on a scale from 0 = not any to 4 = extreme and scores range from 0–20. The overall WOMAC measure and its respective subscales possess high construct validity and test-retest reliability for both paper and computerized versions of the scale.61 In the current study, Cronbach’s α for the WOMAC pain subscale was .89.

Data reduction and analysis

Pearson’s correlations were used to evaluate the associations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, TS of heat pain, as well as other relevant and continuously-measured study variables such at the CES-D and WOMAC. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine between-group differences (e.g., ethnicity and sex) among criterion measures. Multivariate associations, adjusted for control variables as needed, were examined using multiple regressions. Lastly, the bootstrapping technique and macro created and described by Preacher and Hayes41 for obtaining a 95% percentile confidence interval was utilized to test whether pain catastrophizing significantly mediated the association between dispositional optimism and TS of heat pain. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric resampling procedure that has been shown to be a viable alternative to normal-theory tests of the intervening mediator between the independent and dependent variables.66 The percentile confidence interval was incorporated to help minimize potential of Type I error related to the test of the indirect effect.21 Cohen’s d and Cohen’s f2 effect sizes are presented where appropriate for tests of mean differences (t-tests, ANOVA) and linear relationships (bootstrapping), respectively. Per Cohen’s guidelines, d = .2 is considered a small effect, d = .5 a medium-sized effect and d = .8 a large effect. Similarly, f2 = .02 is considered a small effect, f2 = .15 a medium-sized effect and f2 = .35 a large effect. The probability value for acceptable Type I error was set at < .05. All analyses were two-tailed and completed using SPSS, version 19.

Results

Participant characteristics

Descriptive data for key study variables and participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The study was comprised of older, community-dwelling adults with the majority being women, which was to be expected given that women experience knee OA symptoms at a higher rate than men.31 The racial composition of the study’s sample was relatively equal, and the majority of individuals who participated in this study were recruited from the University of Florida site compared to the University of Alabama at Birmingham site.

Table 1.

Descriptive data for participant characteristics and key study variables.

| Variable | Percent (%) | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | 26 | ||

| Women | 74 | ||

| Ethnicity/Race | |||

| non-Hispanic white | 52 | ||

| African American | 48 | ||

| Site | |||

| UF | 86 | ||

| UAB | 14 | ||

| Age | 56.7 (7.2) | 45 – 74 | |

| CES-D | 9.2 (6.9) | 0 – 34 | |

| LOT-R | 17.6 (4.4) | 4 – 24 | |

| CSQ-catastrophizing | 1.6 (1.2) | 0 – 5.3 | |

| WOMAC-pain | 7.3 (4.5) | 0 – 19 | |

| TS of heat | 12.9 (14.8) | 0 – 75 |

Note: Age measured in years; UF = University of Florida, UAB = University of Alabama at Birmingham; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; LOT-R = Life Orientation Test-Revised; CSQ = Coping Strategies Questionnaire; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index of Osteoarthritis; TS = temporal summation.

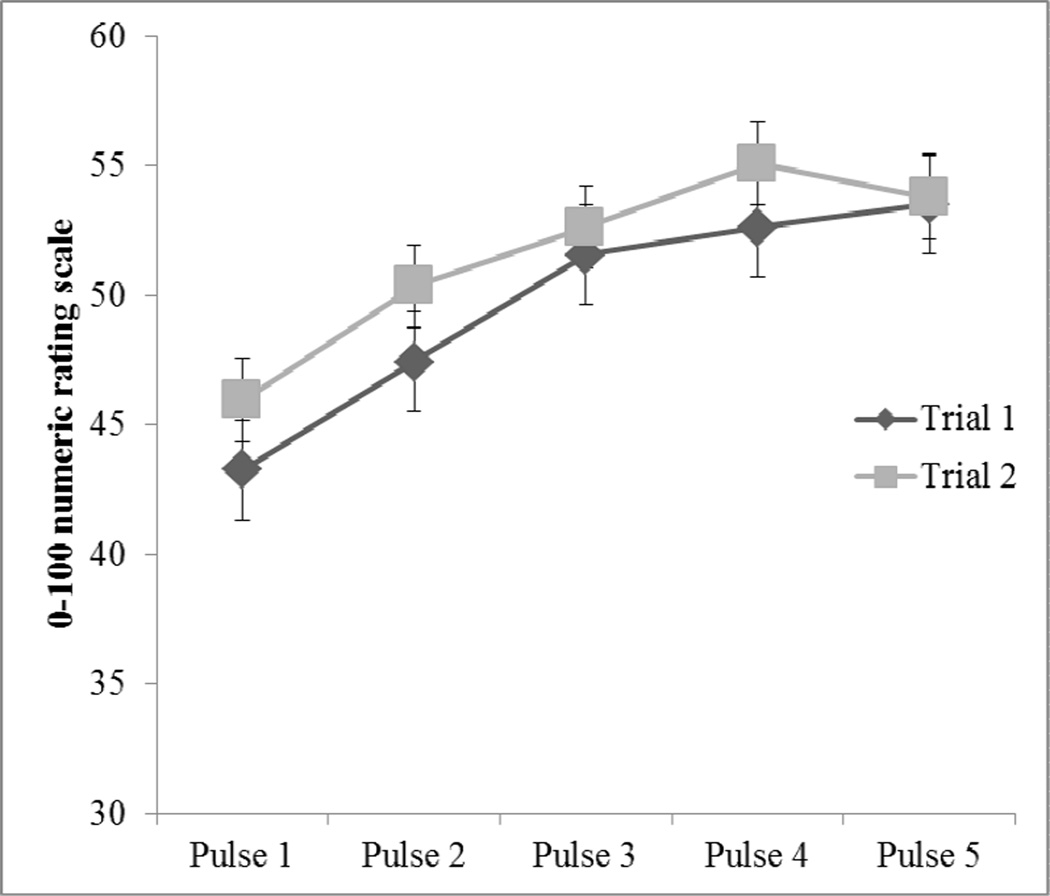

Temporal summation (TS) of heat pain

Paired samples t-tests were completed to compare the first heat pulse pain rating to the highest heat pulse pain rating across the individually tailored and repeated heat pain stimuli. Results revealed that mean highest heat pulse pain ratings were significantly increased from mean first heat pulse pain ratings for Trial 1 t137 = 9.97, p < .001, d = .85 and Trial 2 t137 = 8.80, p < .001, d = .75. These increases in pain ratings represent significant TS of heat pain for both trials (Figure 1). The magnitude of TS (i.e., Δ change scores for Trial 1 and 2) was calculated by subtracting the first pain rating from the highest pain rating. The TS Δ change scores were significantly correlated between Trial 1 and Trial 2 (r = .65, p < .001). As a result, these two TS Δ change scores were averaged together to create an overall TS that was used in subsequent data analysis. Of the four potential tailored thermal intensities (i.e., 44°C, 46°C, 48°C, and 50°C), the percentages of individuals who completed the TS procedure using each of the respective temperatures was as follows: 29% at 44°C, mean TS = 10.71 (17.93); 16% at 46°C, mean TS = 13.14 (14.25); 23% at 48°C, mean TS = 16.30 (12.92); and 32% at 50°C, mean TS = 12.67 (13.51). The overall TS of heat pain did not significantly differ as a function of the different temperatures used to tailor the heat stimulus to a moderate level of pain for each individual in this study (F3,132 = .85, p = .47). This suggests that the tailoring of stimuli was successful in producing a similar magnitude of TS across participants, independent of the intensity of the tailored thermal stimulus used to assess TS.

Figure 1.

Tailored temporal summation of heat pain; NRS = numeric rating scale.

Bivariate associations and examination of statistical covariates

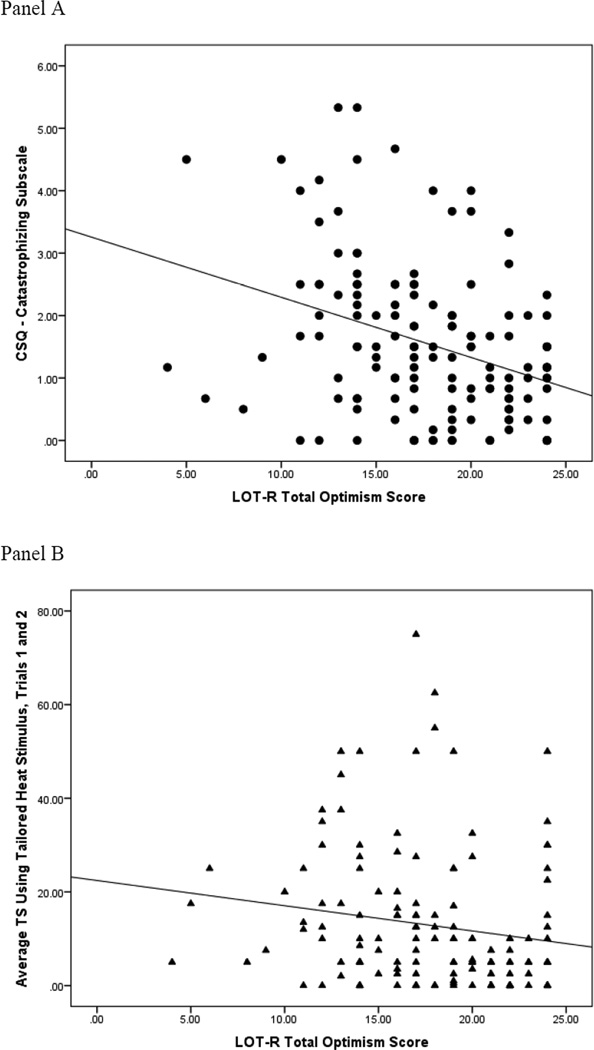

Pearson correlations among continuously-measured variables are shown in Table 2. It was hypothesized that greater dispositional optimism would be associated with lower levels of pain catastrophizing and less TS of heat pain. The LOT-R was significantly and inversely correlated with the catastrophizing subscale of the CSQ (Figure 2, Panel A). Likewise, the LOT-R and TS of heat pain were also significantly and inversely correlated (Figure 2, Panel B). These results indicated that greater dispositional optimism is indeed associated with lower levels of pain catastrophizing and less TS of heat pain.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlations among continuously-measured variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | ||||

| 2. CES-D | −.19* | — | |||

| 3. LOT-R | .14 | −.47** | — | ||

| 4. CSQ-catastrophizing | −.09 | .47** | −.35** | — | |

| 5. WOMAC-pain | −.06 | .42** | −.15 | .53** | — |

| 6. TS of heat | .06 | .03 | −.16* | .21* | −.03 |

p < .05,

p < .01

Note: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression; LOT-R = Life Orientation Test-Revised; CSQ = Coping Strategies Questionnaire; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index of Osteoarthritis; TS = temporal summation.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of the associations between dispositional optimism and pain catastrophizing (Panel A) as well as dispositional optimism and temporal summation of heat pain (Panel B).

Patients’ age did not significantly correlate with any of the key study variables. Reported depressive symptoms on the CES-D were significantly correlated with the LOT-R and the CSQ catastrophizing subscale but not TS of heat pain. Higher levels of clinical pain severity on the WOMAC were significantly and positively correlated with the CSQ catastrophizing subscale. A series of ANOVAs revealed that men and women did not significantly differ on the LOT-R, the catastrophizing subscale of the CSQ, or TS of heat pain. African Americans did not significantly differ from non-Hispanic whites on TS of heat pain or the LOT-R. However, African American patients did report significantly greater pain catastrophizing than non-Hispanic whites on the catastrophizing subscale of the CSQ (F1,138 = 15.09, p < .001, d = 4.43). Ethnic background, CES-D, and the pain subscale of the WOMAC were subsequently included as statistical covariates in multivariate analyses examining the associations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, and TS of heat pain.

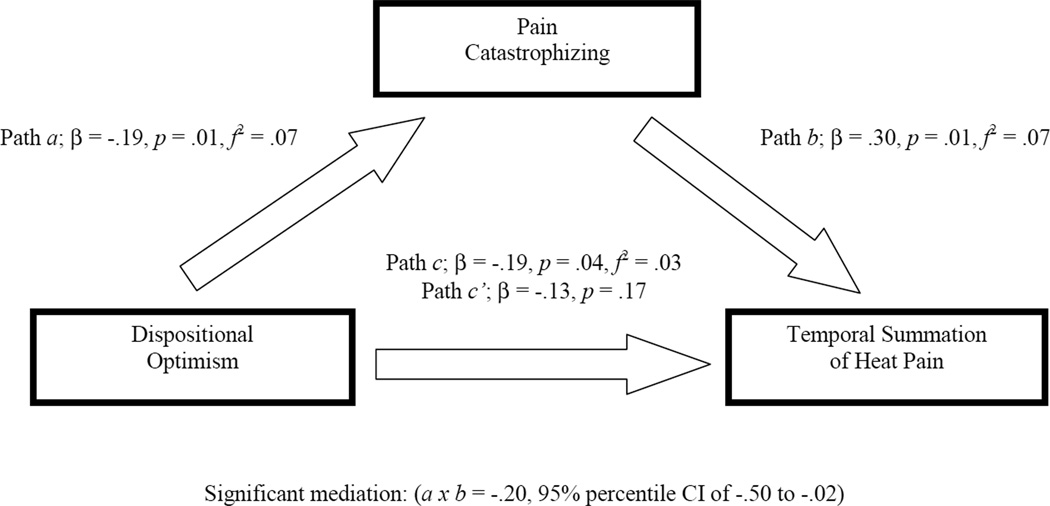

Mediation

To determine if pain catastrophizing significantly mediated the association between dispositional optimism and TS of heat pain, we conducted a bootstrap analysis to estimate the direct and indirect effects (direct effect + indirect effect = total effect). A 95% percentile confidence interval was calculated to determine the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediation) effect. The bootstrapped mediation analysis indicates whether the total effect (path c) of the independent variable (IV; dispositional optimism) on the dependent variable (DV; TS of heat pain) is comprised of a significant direct effect (path c’) of the IV on the DV and a significant indirect effect (path a×b) of the IV on the DV through a proposed mediator (pain catastrophizing). Path a denotes the effect of IV on the mediator, whereas, path b is the effect of the mediator on the DV.

Bootstrapping procedure

The overall mediation model adjusted for covariates shown in Figure 3 accounted for a small, yet significant 9% of the total variance in TS of heat pain (R2 = .09, p = .03). The total effect (path c) of dispositional optimism on TS of heat pain was significant (β = −.19, p = .04, f2 = .03) but the direct effect (path c’) of dispositional optimism on TS of heat pain was not (β = −.13, p = .17). The indirect effect (path a×b) of dispositional optimism on TS of heat pain through pain catastrophizing had a point estimate of −.20 and a 95% percentile confidence interval of −.50 to −.02 with f2 = .16. This confidence interval suggests that, even after controlling for ethnic background, CES-D, and the pain subscale of the WOMAC, the indirect effect of a×b is significantly different from zero (i.e., the null effect) at p < .05. The directions of paths a (β = −.19, p = .01, f2 = .07) and b (β = .30, p = .01, f2 = .07) are consistent with the interpretation that greater dispositional optimism is associated with lower pain catastrophizing, which in turn, is associated with less TS of heat pain. Thus, pain catastrophizing was a significant mediator of the association between dispositional optimism and TS of heat pain. Further, it appears that the total effect of dispositional optimism on TS of heat pain is driven by the indirect effect through pain catastrophizing, rather than the direct effect given the difference in effect size estimates.

Figure 3.

Mediation model representing the indirect association of dispositional optimism with temporal summation of heat pain through pain catastrophizing.

Osteoarthritic pain severity

The LOT-R was not significantly correlated with pain severity on the WOMAC (Table 2); however, the inverse direction of this association was as expected and trended toward significance. The CSQ pain catastrophizing subscale was significantly and positively correlated with WOMAC pain severity. In an adjusted multiple regression analysis controlling for ethnic background and the CES-D, the LOT-R was not significantly associated with WOMAC pain severity (β = −.05, p = .54), yet the association between pain catastrophizing and pain severity remained highly significant (β = .40, p < .001, f2 = .18). Given the lack of a significant association between the LOT-R and the WOMAC pain severity subscale, mediation analyses were not carried out.

Discussion

The present study contributes to a growing body of literature addressing personality characteristics and pain by expanding upon previous research, which has demonstrated the effects of dispositional optimism on endogenous pain processing 27 as well as pain sensitivity 24 and placebo analgesia.9, 23, 39 Specifically, greater dispositional optimism was found to be associated with less pain catastrophizing and less TS of heat pain; further, pain catastrophizing significantly mediated the association between dispositional optimism and TS of heat pain. These associations remained significant even after adjusting for the potentially confounding effects of individuals’ ethnic background, depressive symptoms, and clinical pain severity within the 48 hours prior to completion of the controlled noxious stimulation session. Further, tailoring the stimulus intensity helped to minimize “ceiling effects”, while not systematically affecting TS of heat pain, which represents a methodological strength in this study and further underscores the credibility of the inter-relations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, and TS of heat pain.

Amplified TS has been suggested to represent an important pathophysiologic process that contributes to the development and maintenance of pain states in a number of clinical contexts.17 For example, enhanced TS has been observed in fibromyalgia (FM),7 temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJD),38 and other myofascial pain conditions.47, 50 Whether the TS observed in this sample of older adults with chronic osteoarthritic knee pain is similarly heightened remains unclear, given the lack of comparison made to a control group comprised of healthy older adults. Further, unlike the current study, most previous studies that examined TS in clinical contexts did not tailor the stimulus intensity for each patient to a moderate level of pain, which complicates comparisons with our results. The absence of correlation between TS and the clinical pain indicator in the present study (i.e., WOMAC) is consistent with some prior reports,36, 64 but contrasts with others.2, 56 Although TS has readily been shown to accompany many chronic pain conditions, TS is not an absolute and static phenomenon, but rather one that can be modulated by various neurophysiologic and psychosocial factors.16, 17 In the past, the vast majority of studies that have examined the influence of psychosocial factors on pain facilitatory processes such as TS have focused on risk factors (e.g., fear, anxiety, maladaptive coping strategies) that potentiate TS.16, 25, 44 Conversely, to our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that protective factors such as positive personality traits may help mitigate TS among older individuals with symptomatic OA of the knee. Whether the attenuated TS demonstrated by individuals with greater dispositional optimism translates into less severe reports of pain in everyday life and greater physical functioning is a topic in need of further research.

Pain catastrophizing predicts experimental and clinical pain experiences,40, 63 and the current study’s findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that the protective link between positive personality traits and experimental pain perception operates through lower pain catastrophizing.30 Given that the neurophysiology of TS in humans has not been fully characterized, it remains unclear exactly how dispositional optimism and catastrophizing might influence TS; however, some speculation seems warranted. It has been reported that dispositional optimism may be an important component of psychological resilience.4 Psychological resilience refers to a dynamic process whereby individuals exhibit successful adaptation when they encounter significant adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or other significant sources of stress.34, 40 Psychologically resilient individuals with greater dispositional optimism may be less likely to exhibit maladaptive pain responses such as catastrophizing. Indeed, psychological resilience has previously been shown to predict decreases in pain catastrophizing,40 in the same way dispositional optimism was shown to be related to less pain catastrophizing in this study and others.30 Although no research to date has examined the link between psychological resilience and endogenous pain processing, several functional neuroimaging studies lend credence to the viability of resilience as an explanation for the mediation demonstrated in the current study.13, 52, 55 Psychologically resilient individuals may also simply attend less to their pain, which is important because increased attention to pain has been associated with enhanced processing of nociceptive stimuli perceived to be painful.62 Taken together, the psychological resilience attributed to those with positive personality traits like optimism may impact pain perception by affecting coping strategies and endogenous pain processing as well as their cortical underpinnings. The putative contribution of psychological resilience to endogenous pain processing remains speculative and must be tempered by the fact that, although statistically significant, the relation between dispositional optimism and TS of heat pain was weak with the overall mediation model only accounting for 9% of the variance in TS of heat pain. Similarly, in the previous study conducted by our group,27 the association between dispositional optimism and endogenous pain inhibition (i.e., conditioned pain modulation) was also significant yet small. On balance, the practical relevance of the influence of positive personality traits such as dispositional optimism on endogenous pain processing is yet to be determined.

The current study possesses several limitations that need to be addressed. First, although our study’s model is consistent with prospective findings in which diminished reports of pain catastrophizing significantly mediated individuals’ later experiences of pain,53 the cross-sectional nature of the current study allows for the possibility that the associations among dispositional optimism, pain catastrophizing, and TS of heat pain may be bidirectional or co-occurring. Despite this possibility, similar existing evidence suggests that optimism exerts an indirect effect on health reports through coping strategies,3 and this helps to support the plausibility of the current study’s meditational model. Second, pain catastrophizing was assessed according to the “standard” means of measurement (i.e., recall of catastrophizing in daily life), rather than the “situation-specific” means of measurement (i.e., catastrophizing measured during or directly after the administration of noxious stimulation).11, 12 Standard versus situation-specific measures of pain catastrophizing have been shown to produce differential patterns of relationships with individuals’ pain responses.8 Because pain catastrophizing was only assessed using a standard measure of the CSQ pain catastrophizing subscale, it remains to be determined whether the strength of the associations in this study’s mediation model might differ with the inclusion of a more thorough and situation-specific measure of pain catastrophizing such as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS).58 Third, some level of bias may have been introduced into the study results due to sample selectivity. For example, individuals had to be willing to complete the two session protocol and they were excluded from study participation if they received daily opioid therapy. Fourth, the characteristics of the experimenters (e.g., sex, ethnicity/race) that facilitated the QST sessions were not matched to those of the participants. This is important to note because experimental pain responses have been shown to differ according to whether experimenter characteristics were either matched or unmatched to those of the individual study participants.33 Fifth, the assessment of TS relies upon individuals’ self-report of pain ratings, and as such, TS measurement is susceptible to possible report biases given the subjective nature in which the data are acquired. Future studies examining the association of dispositional optimism with self-report versus reflex-based or brain imaging responses of pain could help distinguish any differential effects of optimism on subjective and objective indices of pain, respectively. Lastly, significant associations were found among key study variables in this sample of older adults with symptomatic OA of the knee. However, results did not reveal a significant association between dispositional optimism and clinical pain reports measured using the pain subscale of the WOMAC. The clinical implications for dispositional optimism in relation to the experience of pain in everyday life among individuals with painful knee osteoarthritis remain unclear. Despite these limitations, the present study does provide novel information related to how positive personality traits might ultimately come to affect individuals’ experience of pain.

In conclusion, the current results, coupled with our previous findings,27 provide mounting evidence that positive personality characteristics such as dispositional optimism may influence endogenous pain processing. One mechanism underlying the link between dispositional optimism and pain facilitatory processes is pain catastrophizing. In light of these findings, a potentially fruitful area of future research may be to address whether cognitive-behavioral treatments that improve pain catastrophizing subsequently affect TS of pain. Indeed, chronic pain patients provided with a trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy have previously been shown to engage in less pain catastrophizing after treatment, which, in turn, was associated with improved pain outcomes.37, 53 Whether the improved pain outcomes in these cognitive-behavioral treatment studies was a function of diminished TS is not known. Further, it remains to be determined whether personality characteristics such as dispositional optimism might interact with cognitive-behavioral treatments that target pain responses such as catastrophizing. For instance, chronic pain patients with higher levels of dispositional optimism may have fewer problems with pain catastrophizing, as suggested in this study, and require less treatment focused on this maladaptive pain response. Conversely, patients with lower levels of dispositional optimism may require additional treatment and assistance in order to effectively manage their pain catastrophizing.

Perspective.

Results from this study further support the body of evidence that attests to the beneficial effects of positive personality traits on pain sensitivity and pain processing. Further, this study identified diminished pain catastrophizing as an important mechanism explaining the inverse relation between dispositional optimism and endogenous pain facilitation.

Acknowledgments

This work supported in part by NIH/NIA Grant R01AG033906-08; NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Florida, UL1 TR000064 and KL2TR000065; NIH/NCATS and NCRR Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, UL1TR000165; NIH Training Grant T32NS045551-06 provided to the University of Florida. The contents are solely the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with this study.

References

- 1.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, Howell D, Kaplan D, Koopman W, Longley S, III, Mankin H, McShane DJ, Medsger T, Meenan R, Mikkelsen W, Moskowitz R, Murphy W, Rothschild B, Segal M, Sokoloff L, Wolfe F. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2010;149:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. Modeling cognitive adaptation: a longitudinal investigation of the impact of individual differences and coping on college adjustment and performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:989–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin DR, Jackson D, III, Okoh I, Cannon RL. Resiliency and optimism: an African American senior citizen’s perspective. J Black Psychol. 2011;37:24–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W. Criterion validity of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in the Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27:231–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of the WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley LA, McKendree-Smith NL, Alarcon GS, Cianfrini LR. Is fibromyalgia a neurologic disease? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:106–114. doi: 10.1007/s11916-002-0006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell CM, Kronfli T, Buenaver LF, Smith MT, Berna C, Haythornthwaite JA, Edwards RR. Situational versus dispositional measurement of catastrophizing: associations with pain responses in multiple samples. J Pain. 2010;11:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello NL, Bradgon EE, Light KC, Sigurdsson A, Bunting S, Grewen K, Maixner W. Temporomandibular disorder and optimism: relationships to ischemic pain sensitivity and interleukin-6. Pain. 2002;100:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devins GM, Orme CM, Costello CG, Binik YM, Frizzell B, Stam HJ, Pullin WM. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Psychol Health. 1988;2:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon KE, Thorn BE, Ward LC. An evaluation of sex differences in psychological and physiological responses to experimentally-induced pain: a path analytic description. Pain. 2004;112:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards RR, Campbell C, Fillingim RB. Catastrophizing and experimental pain sensitivity: only in vivo reports of catastrophic cognitions correlate with pain responses. J Pain. 2005;6:338–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards RR, Campbell C, Jamison RN, Wiech K. The neurobiological underpinnings of coping with pain. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:237–241. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Effects of age on temporal summation and habituation of thermal pain: clinical relevance in healthy older and younger adults. J Pain. 2001;2:307–317. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.25525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards RR, Ness TJ, Weigent DA, Fillingim RB. Individual differences in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC): association with clinical variables. Pain. 2003;106:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards RR, Smith MT, Stonerock G, Haythornthwaite JA. Pain-related catastrophizing in healthy women is associated with greater temporal summation of and reduced habituation to thermal pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:730–737. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210914.72794.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eide PK. Wind-up and the NMDA receptor complex from a clinical perspective. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:5–15. doi: 10.1053/eujp.1999.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell M, Gibson S. Age interacts with stimulus frequency in the temporal summation of pain. Pain Med. 2007;8:514–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Kincaid S, Silva S. Sex differences in temporal summation but not sensory-discriminative processing of thermal pain. Pain. 1998;75:121–127. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritz MS, Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP. Explanation of Two Anomalous Results in Statistical Mediation Analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 2012;47:61–87. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2012.640596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garofalo JP. Perceived optimism and chronic pain. In: Gatchel RJ, Weisberg JN, editors. Personality characteristics of patients with pain. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geers AL, Wellman JA, Fowler SL, Helfer SG, France CR. Dispositional optimism predicts placebo analgesia. J Pain. 2010;11:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geers AL, Wellman JA, Helfer SG, Fowler SL, France CR. Dispositional optimism and thoughts of well-being determine sensitivity to an experimental pain task. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George SZ, Wittmer VT, Fillingim RB, Robinson ME. Fear-avoidance beliefs and temporal summation of evoked thermal pain influence self-report of disability in patients with chronic low back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:92–105. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-9007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodin BR, King CD, Sibille K, Glover T, Bradley L, Fillingim RB. Greater dispositional optimism is related to diminished temporal summation of heat pain in older adults with knee pain with and without radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis. J Pain. 2012;13(4, supp):S105. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodin BR, Kronfli T, King CD, Glover TL, Sibille K, Fillingim RB. Testing the relation between dispositional optimism and conditioned pain modulation: does ethnicity matter? J Behav Med. 2012 Feb 25; doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9411-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodin BR, McGuire L, Allshouse M, Stapleton L, Haythornthwaite JA, Burns N, Mayes LA, Edwards RR. Associations between catastrophizing and endogenous pain-inhibitory processes: sex differences. J Pain. 2009;10:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haack M, Scott-Sutherland J, Santangelo G, Simpson NS, Sethna N, Mullington JM. Pain sensitivity and modulation in primary insomnia. Eur J Pain. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hood A, Pulvers K, Carrillo J, Merchant J, Thomas MD. Positive traits linked to less pain through lower pain catastrophizing. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;52:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter DJ, McDougall JJ, Keefe FJ. The symptoms of OA and the genesis of pain. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34:623–643. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen MP, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Romano JM, Turner JA. One- and two-item measures of pain beliefs and coping strategies. Pain. 2003;104:453–469. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kallai I, Barke A, Voss U. The effects of experimenter characteristics on pain reports in women and men. Pain. 2004;112:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karoly P, Ruehlman LS. Psychological “resilience” and its correlates in chronic pain: findings from a national community sample. Pain. 2006;123:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keefe FJ, Lumley M, Anderson T, Lynch T, Carson KL. Pain and emotion: new research directions. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:587–607. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kindler LL, Valencia C, Fillingim RB, George SZ. Sex differences in experimental and clinical pain sensitivity for patients with shoulder pain. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litt MD, Shafer DM, Ibanez CR, Kreutzer DL, Tawfik-Yonkers Z. Momentary pain and coping in temporomandibular disorder pain: exploring the mechanisms of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronic pain. Pain. 2009;145:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Sigurdsson A, Kincaid S, Silva S. Sensitivity of patients with painful temporomandibular disorders to experimentally evoked pain: evidence for altered temporal summation of pain. Pain. 1998;76:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton DL, Watson A, El-Deredy W, Jones AK. Reproducibility of placebo analgesia: effect of dispositional optimism. Pain. 2009;146:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Reid MC. Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0019384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psych Bull. 2005;131:925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhudy JL, Martin SL, Terry EL, France CR, Bartley EJ, DelVentura JL, Kerr KL. Pain catastrophizing is related to temporal summation of pain but not temporal summation of the nociceptive flexion reflex. Pain. 2011;152:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosentiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB, Steward WT. Emotional states and physical health. Am Psychol. 2000;55:110–121. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarlani E, Grace EG, Reynolds MA, Greenspan JD. Evidence of up-regulated central nociceptive processing in patients with masticatory myofascial pain. J Orofac Pain. 2004;18:41–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartzman RJ, Alexander GM, Grothusen J. Pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:669–681. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: and introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimistic bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smeets RJEM, Vlaeyen JWS, Kester ADM, Knottnerus A. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2006;7:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Staud R, Cannon RC, Mauderli AP, Robinson ME, Price DD, Vierck CJ. Temporal summation of pain from mechanical stimulation of muscle tissue in normal controls and subjects with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. 2003;102:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Staud R, Craggs JG, Robinson ME, Perlstein WM, Price DD. Brain activity related to temporal summation of C-fiber evoked pain. Pain. 2007;129:130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staud R, Robinson ME, Vierck CJ, Cannon RC, Mauderli AP, Price DD. Ratings of experimental pain and pain-related negative affect predict clinical pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. 2003;105:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staud R, Vierck CJ, Cannon RC, Mauderli AP, Price DD. Abnormal sensitization and temporal summation of second pain (wind-up) in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. 2001;91:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tennen H, Affleck G, Urrows S, Higgins P, Mendola R. Perceiving control, construing benefits, and daily processes in rheumatoid arthritis. Can J Behav Sci. 1992;24:186–203. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Theiler R, Spielberger J, Bischoff HA, Bellamy N, Huber J, Kroesen S. Clinical evaluation of the WOMAC 3.0 OA index in number rating scale format using a computerized touch screen version. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:479–481. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tracey I, Ploghaus A, Gati JS, Clare S, Smith S, Menon RS, Matthews PM. Imaging attentional modulation of pain in the periaqueductal gray in humans. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2748–2752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02748.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uysal A, Lu Q. Self-handicapping and pain catastrophizing. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;49:502–505. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valencia C, Fillingim RB, George SZ. Suprathreshold heat pain response is associated with clinical pain intensity for patients with shoulder pain. J Pain. 2011;12:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vierck CJ, Cannon RL, Fry G, Maixner W, Whitsel BL. Characteristics of temporal summation of second pain sensations elicited by brief contact of glabrous skin by a preheated thermode. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:992–1002. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams J, MacKinnon DP. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2008;15:23–51. doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zautra AJ, Johnson LM, Davis MC. Positive affect as a source of resilience for women with chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:212–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]