Abstract

The microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH) and soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) enzymes exist in a variety of cells and tissues, including liver, kidney and testis. However, very little is known about brain epoxide hydrolases. Here we report the expression, localization and subcellular distribution of mEH and sEH in cultured neonatal rat cortical astrocytes by immunocytochemistry, subcellular fractionation, western blotting and radiometric enzyme assays. Our results showed a diffused immunofluorescence pattern for mEH, which co-localized with the astroglial cytoskeletal marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The GFAP-positive cells also expressed sEH which was mainly localized in the cytoplasm especially in and around the nucleus. Western blot analyses, revealed a distinct protein band with a molecular mass of ~50 kDa, the signal intensity of which increased about 1.5-fold in the microsomal fraction over the whole cell lysate and other subcellular fractions. The polyclonal anti-human sEH rabbit serum recognized a protein band with a molecular mass similar to that of purified sEH protein (~62 kDa), and the signal intensity increased 1.7-fold in the 105,000×g supernatant fraction over the cell lysate. Although the corresponding mEH enzyme activities generally corroborated with the immunocytochemical and western blotting data a low sEH enzyme activity was detected especially in the total cell lysate and in the soluble fractions. These results suggest that rat brain cortical astrocytes differentially co-express mEH and sEH enzymes. The differential subcellular localization of mEH and sEH may play a role in the cerebrovascular functions that are known to be affected by brain-derived vasoactive epoxides.

Keywords: Astrocytes, Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), microsomal epoxide hydrolase, soluble epoxide hydrolase

Mammals employ various enzymatic pathways to metabolize drugs and chemical compounds. Epoxide hydrolases (EH, EC3.3.2.3) are among the enzymes involved in metabolism of epoxides (DuTeaux et al., 2004; Enayetallah et al., 2004; Lu and Miwa 1980; Minn et al., 1991; Ravindranath et al., 1995; Wixtrom and Hammock, 1985). Although there are several EHs (Enayetallah et al., 2005), the two most studied EHs are the microsomal (EPHX 1; mEH) and soluble (EPHX2; sEH) forms which are known to be distributed largely in the microsomal and soluble fractions, respectively.

The mEH appears to metabolize the xenobiotic epoxides, some of which are otherwise mutagenic, carcinogenic and cytotoxic, into more water soluble diols (Hammock and Ota, 1983). The sEH metabolizes xenobiotics but also endogenous epoxides of sterols and fatty acids (Arand et al., 2005; Chacos et al., 1983; Guengerich, 2003). Some of these endogenous epoxides and/or their vic-diols appear to be the substrates for further metabolism by other enzymes such as cyclooxygenases (Ellis et al. 1990) and the products have multiple biological functions, including blood pressure regulation (Capdevila et al., 2000; Imig et al., 2002), and inflammation (Node et al., 1999). Emerging data demonstrate that sEH may be a potential therapeutic target site for the treatment of certain cancer types, hypertension (Jung et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2004), pain and inflammation (Morisseau and Hammock, 2005; Schmeltzer et al., 2005).

The mEH and sEH enzyme activities and their expression have been well characterized in liver and extrahepatic tissues including, kidney, pancreas, and testis (DiBiasio et al., 1991; Draper and Hammock, 1999; Enayetallah et al., 2005; Hammock and Ota, 1983; Moody et al., 1986). The mEH and sEH immunoreactivities correspond to the proteins with molecular masses of 50 kDa and 62.5 kDa, respectively (DuTeaux et al., 2004).

Immunohistological and immunocytochemical studies have shown that the mEH is distributed mainly in the membranes of endoplasmic reticulum and appears diffused in the cell cytoplasm and nuclear membrane. However, mEH can be dislodged from the membrane under different conditions. The sEH, on the other hand, is shown to be localized mainly in the peroxisomes and lysosomes and appears more “punctate” or granular form (Enayetallah et al., 2005; 2006).

Very little is known about the expression and cellular localization of mEH and sEH in the brain (Schilter and Omiecinski, 1993; Zhang et al. 2007). Nonetheless, previous studies have shown that sEH activity is responsible for the rapid conversion of cytochrome P450-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) in the homogenates of cultured astrocytes from neonatal rat hippocampus or the cortex (Amruthesh et al., 1993; Shivachar et al., 1995). Here we report the differential sub-cellular distribution of mEH and sEH by immunocytochemical double labeling, western blotting, and enzymatic analyses in various subcellular fractions of neonatal rat cortical astrocytes. Our results show that mEH and sEH are colocalized in cells that express astroglial marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The sEH immunoreactivity and enzyme activity were enriched in 105,000×g supernatant, and a minor portion was also found distributed in mitochondrial and nuclear fractions. However, mEH immunoreactivity and enzyme activities were distributed among microsomal, mitochondrial and nuclear fractions. These results suggest that astrocytes co-express both microsomal and soluble EHs which may play a central role in the cerebrovascular functions. The differential distribution of EH proteins and/or enzyme activities in various subcellular fractions of astrocytes may be of great significance for our understanding of the possible role of cytochrome P450-arachidonic acid epoxides in the regulation of various brain diseases, including ischemia, stroke Alzheimer’s and cancer.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was obtained from Atlanta Biological, (Lawrenceville, GA , USA ), penicillin/streptomycin mixture (prepared with 10,000 U/ml of penicillin G sodium and 10,000µg/ml of streptomycin sulfate in saline) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St.Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum was from Nova-Tech (Grand Island, NE). The radioactive compounds [3H]-cis-stilbene oxide (0.555–1.11 Tbq/mmol) and [3H], trans-1, 3-dipenylpropene oxide (tDPPO) were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc (St. Louis, MO). The primary antibodies used were polyclonal anti-goat IgG antibody to mEH (Oxford MI, USA), polyclonal anti-rat IgG antibody to mEH, and rabbit polyclonal anti-human IgG antibody to sEH (Enayetallah et al., 2004). The affinity-purified sEH protein (Enayetallah et al., 2004) was used as a positive control. Mouse anti-Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) cocktail was from Research Diagnostics Inc., {(RDI) Flanders, NJ}. Horse Radish Peroxidase conjugated anti-goat IgG, anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) conjugated secondary antibody probes, Cruz markers, anti β-actin IgG, and Western Blotting Luminol Reagent were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, (Santa Cruz, CA). Auto radiographic hyper film was obtained from Molecular Technologies, (St.Louis, Missouri, USA). All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from BD Biosciences (VWR International, Inc., West Chester, PA) and/or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2 Cell Culture

Primary cultures of rat cortical astrocytes were prepared by dissecting cerebral cortices from 1–2 day-old Sprague Dawley rat pups under aseptic conditions as previously described (Shivachar et al., 1995; Shivachar, 2007). Purity of the astrocytes was assayed Immunocytochemically by staining with Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP).

2.3 Immunocytochemistry

Primary cultures of astrocytes were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and lifted by trypsinization in 0.15% trypsin (Sigma, St.Louis, MO) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing EDTA (1mM). The cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 200 ×g, and the pellet was suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (10,000 U/10µg/ml) for cell counting. Approximately 10,000 cells in 400µl of medium were plated on round, sterile glass coverslips (12mm diameter). Cells were allowed to adhere for 2–3 hrs, then flooded with fresh medium and incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After 24 hr, the medium was removed, the attached cells were washed three times with PBS and then fixed for 10 min in cold (−10 C) methanol. Methanol was aspirated and the coverslip was allowed to air dry completely, wrapped in parafilm, and stored in a humidity-free chamber at −20°C until further use.

Fixed cells were rehydrated with PBS and blocked for 1 h with 5% BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) in PBS. Subsequently, cells were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti - goat mEH IgG, (dilution 1:200) or polyclonal anti-human sEH rabbit serum (dilution 1:250) in 2.5% BSA in PBS. After the incubation, cells were gently washed three times with PBS and incubated with anti-mouse GFAP IgG (cocktail, (dilution, 1:500) in 2.5% BSA-PBS for 1hr at room temperature. The cells were washed and then incubated for an hour simultaneously with the appropriate secondary antibodies (1:500dilution) conjugated with TRITC or FITC. After the incubation (1hr), cells were washed and stained the nuclei with DAPI-10µg/ml (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). To rule out any nonspecific staining, controls were simultaneously incubated by omitting the primary antibody and then with only the secondary antibodies.

The fluorescence was viewed using a Nikon Inverted Fluorescence Microscope ECLIPSE TS100 equipped with CCD camera. Images were captured using MetaVue software (Meta Imaging Software, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The number of cells showing colocalization of GFAP and EH were counted at least in three different fields for percent calculations after merging the images.

2.4 Subcellular fractionation

The whole cell lysate was prepared from astrocytes by homogenizing in 3 volumes of ice-cold 0.25M sucrose solution, containing 3mM MgCl2 and protease inhibitors (pepstatin1µg/ml,aprotinin1µg/ml, leupeptin1µg/ml and PMSF 1mM) and dithiothreitol (10mM). This cell lysate was then centrifuged for 10 min at 600 × g. The pellet (P1) and the supernatant (S1) fractions were subjected to prepare relatively enriched nuclear, mitochondrial, microsomal and soluble fractions by the method of Pacifici et al (1988). Briefly, the P1 fraction was used for isolating nuclei by suspending in the original volume 0.25M sucrose solution and centrifuged for 10 min at 600g. This step was repeated twice and the resulting pellet was then suspended in 2.3 M sucrose, containing 3mM MgCl2 and centrifuged at 50,000×g for 60 min at 4°C in an ultracentrifuge (Kendro Laboratory Products, USA). The pellet was suspended in 1M sucrose containing 1mM MgCl2, centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 min and this step was repeated four times. The final pellet was suspended in 0.25M sucrose solution containing 3mM MgCl2 to constitute the nuclear fraction.

Next, the S1 fraction was centrifuged for 15 min at 9000×g to sediment mitochondria. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 105,000×g for 60 min at 4°C in an ultracentrifuge to separate the microsomal (pellet) from the soluble (supernatant) fraction. The mitochondrial and microsomal pellets were suspended in 0.25M sucrose solution, containing 3mM MgCl2. Aliquots of 105,000×g supernatant, microsomal, mitochondrial, and nuclear fractions thus obtained were stored at −80°C up to 1 week for western blotting and /or enzymatic assay.

2.5 Western blotting

Aliquots of whole cell lysate, nuclear, mitochondrial, and microsomal or the soluble fractions (10µg protein each), dissolved in 5x Laemmeli’s gel loading buffer, were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Affinity purified sEH protein (2ng) was used as positive control. The separated proteins were transferred to a 0.45 µm PVDF (Polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes (Pall Corporation, FL), blocked with 10% nonfat dry milk (w/v) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (v/v) and incubated overnight either with goat polyclonal anti-rabbit mEH IgG (dilution 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-rat mEH IgG (1:500) or rabbit polyclonal anti-human sEH serum (dilution1:1000) for microsomal and cytosolic epoxide hydrolases, respectively. Blots were subsequently washed and incubated for 1h at room temperature with anti-goat or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (dilution 1:2500) in 5% blocking buffer. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Western Blotting Luminol Reagent.

Blots were then stripped for 30 min at 50°C in stripping buffer, pH 6.8 (62.5 mM Tris–HCl, 2% SDS, and 100 mM 2-β–mercaptoethanol), washed three times with PBS and probed overnight with goat polyclonal β-actin IgG (dilution 1:1000) as a further measure of protein loaded. The washed blots were incubated overnight with anti-goat IgG -HRP conjugated antibody and immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the Western Blotting Luminol Reagent.

2.6 Radiometric assay of mEH and sEH activity

The enzyme activities of mEH and sEH were quantitatively estimated in the whole cell lysate, nuclear, mitochondrial, microsomal and soluble fractions using mEH- and sEH-selective radioactive substrates as previously described (Gill et al. 1983; Boran et al. 1995). The sEH activity in the 20-fold diluted samples were measured in sodium phosphate buffer (0.1M, pH 7–4) containing 0.1 mg/ml of BSA in glass tubes. The assay was initiated by mixing 100 µl of the samples with 1ml of sEH –selective substrate [3H]-trans -1,3-Diphenylpropene oxide (tDPPO) dissolved in DMF at 5mM ([S]final=50µM). The reaction mixture was immediately incubated for 50 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 60µl of methanol, and extracted with 200µl of isooctane, which extracts the remaining epoxide from the aqueous phase. The mEH activity in the 20-fold diluted samples were measured in Tris/HCl buffer (0.1M, pH 9.0) containing 0.1mg/ml of BSA in glass tubes. The assay was initiated by mixing 100µl of the cell samples with 1µl of [3H]-cis Stilbene oxide (cSO) dissolved in ethanol at 5mM ([S] final= 50µM). The reaction mixture was immediately incubated for 120 minutes at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 250µL of isooctane, which also extracts the remaining epoxide from the aqueous phase. For both assays control reactions for glutathione-transferase activities were extracted with hexanol in place of isooctane. The activities were followed by measuring the quantity of radioactive diol in the aqueous phase using a liquid scintillation counter (Wallac Model 1409, Gaithersburg, MD).

2.7 Protein analysis

The protein concentrations in the total cell lysate and in the subcellular fractions were measured by the (Bradford, 1970) dye binding method according to the procedure described by manufacturer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

2.8 Data analysis

The Immunoblots were scanned using External Laser Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX, Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Quantity One 1-D Analysis software (Bio-Rad laboratories, CA, USA) was used to analyze the intensities of the immunoreactive protein bands in the immunoblots. Enzyme activity was expressed as mean ± SD specific activity calculated from three independent experiments from three different batches of confluent cell cultures.

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Colocalization of mEH and sEH in rat cortical astrocytes

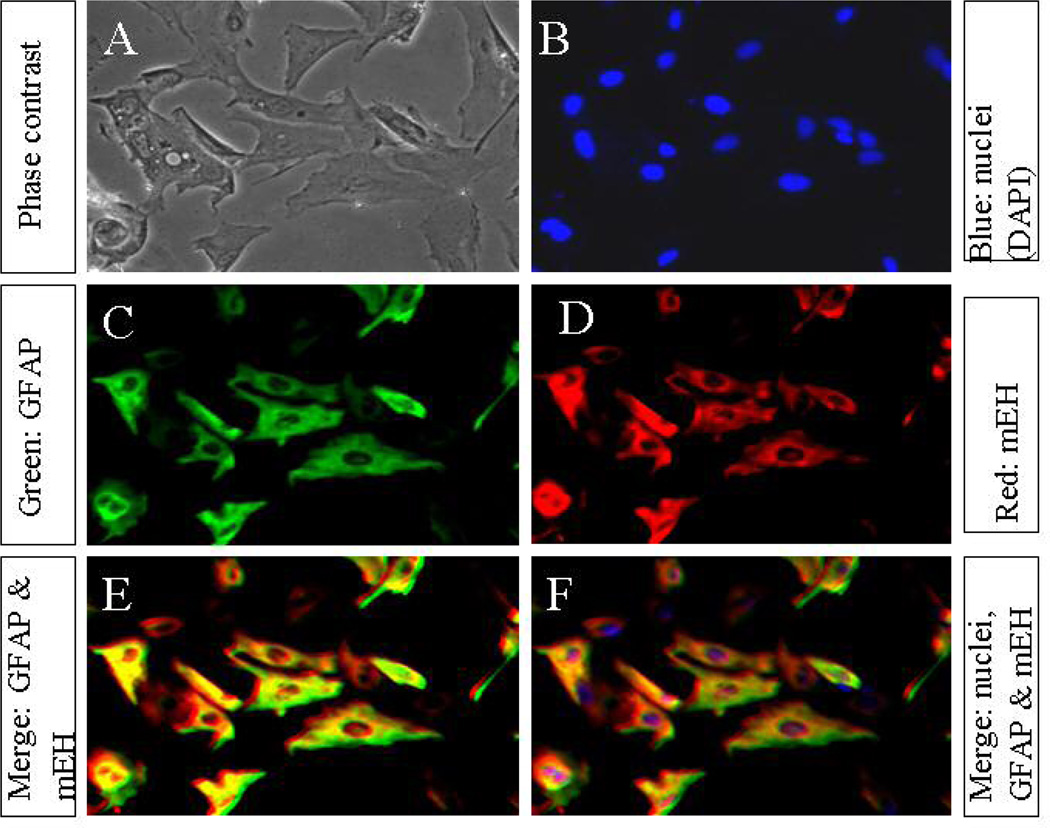

The phase contrast microscopic examination of methanol-fixed cell monolayer revealed that our culture conditions yielded uniform, flat monolayer of polygonal cells (Fig.1, Panel A). Nuclear staining with DAPI showed each cell contained a conspicuous nucleus homogenous in size and shape depicting the normal cell growth (Fig.1, Panel B). Immunocytochemical staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a cytoskeletal protein marker for astrocytes, revealed that more than 95% cells in culture were GFAP-positive (Fig.1, Panel C), and closely resembled the morphology of type-1 astrocytes as previously reported (Amruthesh et al., 1993). We next performed the immunocytochemical double staining to determine whether any of these cells that express GFAP also express EH protein. Immunocytochemical double staining of astrocytes for mEH using TRITC conjugated secondary antibody (Fig.1, Panel D; red fluorescence) showed diffused staining patterns as compared to the high abundance of GFAP (Fig.1, Panel C; green fluorescence). We also noted a very dense mEH staining, especially outside of the nuclear membrane corresponding to the microsomes on the endoplasmic reticular membrane. Merging of images in Panels C and D showed that the cells which were positive for GFAP were also positive for mEH and the cells appeared yellowish red (Fig.3, Panels E and F), indicating 100% co-localization. The controls that were incubated with only secondary antibodies showed no detectable immunofluorescence, indicating specificity.

Figure 1. Immunofluorescence co-localization of GFAP and mEH in cultured astrocytes.

The secondary cultures of neonatal rat cortical astrocytes (10,000 cells, A–F), grown on coverslips, were methanol-fixed, double-stained with immunofluorescent probes for GFAP, and mEH proteins and then visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. (A) Typical phase contrast view of the total number of flat monolayer of polygonal cells in a given field. (B) Nuclear staining with DAPI showing the nuclei (blue fluorescence) in the corresponding field. (C) Shows GFAP-positive cells in the same field, stained green with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. (D) Cells in the corresponding field showing the expression of mEH protein, stained red with TRITC conjugated secondary antibody. (E and F) Co-localization of GFAP- and mEH proteins by merging the images (B, C and D) showing obvious cytosolic co-localization appearing yellowish-red immunofluorescence. The photomicrographs (A–F) at magnification 20X represent a typical field on one of three preparations from three different experiments.

Figure 3. Immunofluorescence co-localization of mEH and sEH in cultured astrocytes.

The secondary cultures of neonatal rat cortical astrocytes (10,000 cells, A–F)), grown on coverslips, were methanol-fixed, double-stained with immunofluorescent probes for mEH, and sEH proteins and then visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. (A) Typical phase contrast view of the total number of flat monolayer of polygonal cells in a given field. (B) Nuclear staining with DAPI showing the nuclei (blue fluorescence) in the corresponding field. (C) Shows mEH-positive cells in the same field, stained red with TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody. (D) Cells in the corresponding field showing the expression of sEH protein in the cytosol as well as the nucleus green with FITCconjugated secondary antibody. (E and F) Co-localization of mEH and sEH proteins in the cytosol, after merging the images (B, and C), which appeared yellowish-red immunofluorescence, while the non-merged nucleus appeared bright green. (F) Colocalization of nuclear stain DAPI with GFAP and sEH (B, C and D), appearing yellowish red cytosol and blue-green nucleus. The photomicrographs (A–F) at magnification 20X represent a typical field on one of three preparations from three different experiments.

We next performed the immunocytochemical double staining to determine whether any of these cells that express GFAP also express sEH protein (Fig.2, Panel A; phase contrast images; Panel B; DAPI staining of nuclei). A high abundance of GFAP was apparent in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 2, Panel C; green fluorescence), implying that they were astroglial cells. Overnight exposure of astrocytes to polyclonal anti-human sEH rabbit serum (1:250 dilutions) showed more prominent fluorescence. Dense staining was seen in and around the nucleus (Fig. 2, panel D; red fluorescence). Merging of sEH and GFAP stained cells resulted in co-localization in few astrocytes and only in the cytosolic region leaving bright non-merged reddish nuclei (Fig.2, panel E). Merging with the DAPI-stained nuclei resulted in purple colored nuclei (fig.2, Panel F), implying colocalization. These results indicate a compartment-specific distribution of sEH expressed in few astrocytes especially in the nucleus and perinuclear membranes.

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence co-localization of GFAP and sEH in cultured astrocytes.

The secondary cultures of neonatal rat cortical astrocytes (10,000 cells, A–F)), grown on coverslips, were methanol-fixed, double-stained with immunofluorescent probes for GFAP, and sEH proteins and then visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy. (A) Typical phase contrast view of the total number of flat monolayer of polygonal cells in a given field. (B) Nuclear staining with DAPI showing the nuclei (blue fluorescence) in the corresponding field. (C) Shows GFAP-positive cells in the same field, stained green with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. (D) Cells in the corresponding field showing the expression of sEH protein, stained the cytosol as well as the nucleus red with TRITC conjugated secondary antibody. (E) Co-localization of GFAP- and sEH proteins in the cytosol, after merging the images (B, and C), appearing yellowish-red immunofluorescence, while the non-merged nucleus appeared bright red. (F) Colocalization of nuclear stain DAPI with GFAP and sEH (B, C and D), appearing yellowish red cytosol and Magenta-colored nucleus. The photomicrographs (A-F) at magnification 20X represent a typical field on one of three preparations from three different experiments.

We next performed the immunocytochemical double-staining for sEH and mEH using the polyclonal antibodies (Fig.3, Panels A–F). The mEH immunoreactivity (Panel C; red fluorescence) was more conspicuous in the cytosol while the sEH immunoreactivity (Panel D; green fluorescence) appeared in some cytosolic regions and heavily concentrated in the nucleus. An overlay with mEH appeared greenish yellow only in the cytosol, showing co-localization of mEH and sEH in the cytosol, but sEH remained green in the nucleus (panel E), indicating only sEH is in the nucleus. Furthermore, merging with DAPI (panel B) yielded purple colored nuclei (Panel F), indicating colocalization of sEH with nuclear-specific stain DAPI. These results clearly indicate that in astrocytes sEH immunoreactivity appeared to be in both cytosol and in the nucleus while mEH is mostly restricted in the cytosol, especially around the nucleus.

3.2 Immunodetection of EHs in astrocyte sub-cellular fractions

To further confirm the immunocytochemical results, we next performed western blot analyses in the various subcellular fractions after separation by SDS-PAGE. Our results show that the goat polyclonal anti-rabbit mEH IgG (Fig.4; Panel A) detected an immunoreactive protein band with molecular mass around 50 kDa in the cortical astroglial cell lysate (lane 1), mitochondrial (lane 2), microsomal (lane 3), and nuclear fractions (lane 4). However, no immunoreactivity was detected in the 105,000 × g supernatant fractions (lane 5). When the immunoreactive bands were normalized by reprobing with antibodies for β-actin (panel B), the ratio of immunoreactive band intensities was increased about 1.5 fold in the microsomal fraction (panel B) over the whole cell lysate.

Figure 4. Representative Immunoblots showing mEH (A) and sEH (D) immunoreactivity.

Cell lysate, from the secondary cultures of neonatal rat cortical astrocytes, was subjected to subcellular fractionation as described previously (Pacifici et al., 1988), the proteins (10µg each) from various fractions were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes for visualizing specific immunoreactivity after incubating with primary and HRP-conjugated secondary mEH and sEH antibodies. (A) Immunoblot showing mEH immunoreactive protein bands in the cell lysate (lane1), mitochondrial fraction (Lane 2), microsomal fraction (lanes 3), nuclear fraction (lane 4), 105,000×g supernatant (soluble) fraction (lane 5), and affinity-purified soluble epoxide hydrolase protein (lane6; 2ng protein), respectively. The mEH protein immunoreactivity was distinct at 50 KDa. The immunoreactivity of β-actin protein was used as loading control after stripping and reprobing the above blot with polyclonal anti-β-actin IgG (1:1000 dilutions) to check the amount of the protein loaded in all the wells as described under Materials and methods Section. (B) The bar graphs depict the ratio of mEH to β-actin in cell lysate, mitochondrial, microsomal, nuclear and soluble fractions corresponding to lanes 1–5, respectively, and expressed as arbitrary units of signal intensity. (C) Immunoblot showing sEH immunoreactive protein bands in the cell lysate (lane1), mitochondrial fraction (Lane 2), microsomal fraction (lanes 3), nuclear fraction (lane 4), 105,000×g supernatant (soluble) fraction (lane 5), and affinity-purified soluble epoxide hydrolase protein (lane 6; 2ng protein), respectively. The molecular mass of affinity purified sEH protein corresponded to ~62 KDa. The immunoreactivity of β-actin protein was used as loading control after stripping and reprobing the above blot with polyclonal anti-β-actin IgG (1:1000 dilutions) to check the amount of the protein loaded in all the wells as described under Materials and methods Section. (D) The bar graphs depict the ratio of sEH to β-actin in cell lysate, mitochondrial, microsomal, nuclear and soluble fractions corresponding to lanes 1–5, respectively, and expressed as arbitrary units of signal intensity. The blots shown are representatives of four repetitions.

We next probed the immunoblot with rabbit polyclonal anti-human sEH rabbit serum. Our results showed an immunoreactive band corresponding to ~62kDa in the whole cell lysate, mitochondrial, nuclear and in the 105,000×g supernatant fractions (Panel C, lanes 1, 2, 4 and 5) and the molecular weight was comparable to that of the purified sEH protein loaded as a positive control (fig.4, panel C, lane 6), indicating the expression of sEH protein in cortical astrocytes. The ratio of sEH/β-actin was enriched mainly in the nuclear and 105,000Xg supernatant fractions about 1.3 and 1.7 fold, respectively, over that of the cell lysate. There was no cross reactivity between polyclonal anti-human sEH IgG and polyclonal anti-rat mEH IgG as the latter failed to recognize the microsomal fraction (Panel C, lane 3)...

To determine whether the EH protein distribution in the subcellular fractions, corresponds to EH enzyme activities in the mitochondrial, microsomal, nuclear and soluble fractions relative to the total cell lysate. Table 1 shows the specific activities of sEH and mEH enzymes in various subcellular fractions of astroglial cell lysate. The crude cell lysate of astroglial cells showed measurable mEH activity in some subcellular fractions corroborating with the results of western blotting and immunocytochemical studies. However, under our assay conditions, a low sEH activity was detected in the total cell lysate, nuclear and soluble fractions.

Table 1.

The distribution of mEH and sEH enzyme activities in various subcellular fractions of astrocytes. The enzyme activities are measured by radiometric assays using mEH- and sEH-selective radioactive cSO, or tDPPO substrates, respectively as described in Materials and Methods section. Results are expressed as specific activity per nmol.min−1.mg−1of cell protein. Values in parentheses represent % specific activity normalized to 100% in total cell lysate for comparison among various subcellular fractions. Values are average specific activity ± SD from three independent experiments from three different cell preparations done in replicates of samples assessed for enzyme activity. ND; not detectable under the experimental conditions used in this study.

| Cellular fractions | [3H] cSO Hydrolysis nmol/min/mg cell protein (% specific Activity) |

[3H] tDPPO Hydrolysis nmol/min/mg cell protein (% specific activity) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Cell Lysate | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.3± 0.1 |

| 3000 × g Pellet (Nuclear) | 0.14 ± 0.04 | < 0.3±0.1 |

| 9000 × g Pellet (Mitochondrial) | 0.13 ± 0.07 | ND |

| 105,000 × g Pellet (Microsomal) | 0.17 ± 0.06 | ND |

| 105,000 × g Supernatant (Soluble) | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.5 ± 0.7 |

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that mEH and sEH are co-localized in neonatal rat brain cells that express the astroglial marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). By immunocytochemistry, western blotting and enzymatic assays with selective substrates, we show that a low sEH is mainly distributed in the 105,000×g supernatant, and a minor portion is also distributed in, mitochondrial and nuclear fractions. On the contrary, mEH immunoreactivity was enriched mainly in microsomal and mitochondrial fractions with no clear enrichment in the enzyme activities in any one of the specific compartments. These results suggest that neonatal rat cortical astrocytes coexpress both mEH and sEH. However, the latter was found distributed mainly in the nuclear fractions of few astrocytes and showed relatively low enzyme activity. .

The results of the present study are consistent with our previous reports showing a rapid metabolic conversion of 14,15-EET to its vic diol by rat hippocampal astrocytes, and rat cortical astrocytes (Amruthesh et al., 1993; Shivachar et al., 1995), Our present results regarding distribution of sEH in more than one subcellular fractions is in agreement with a previous study which demonstrated that sEH is both cytosolic and peroxisomal in human hepatocytes, and in renal proximal tubules, while exclusively cytosolic in cells from various other tissues (Enayetallah et al., 2006). However, the authors did not include the brain tissue in their study. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the co-localization of both sEH and mEH and their relative distribution in various subcellular compartments of cultured astrocytes. The immunocytochemical detection of sEH inside and around the nucleus corroborated with our western blot and enzymatic analyses, suggesting that sEH is indeed distributed in soluble and nuclear fractions.

The immunocytochemical and western blotting data regarding mEH distribution revealed that mEH was enriched in the microsomal fraction. While immunocytochemical data revealed that mEH is more diffused throughout the cytosol, sEH appeared more granular and highly localized, specifically around the nuclear membrane and inside the nucleus. The presence of sEH protein in astrocyte cell lysate corroborated with previous studies documenting the presence of a robust EH activity, hydrolyzing the epoxides from cytochrome P450 epoxygenase metabolism of arachidonic acid to their vic-diols in astrocytes from rat hippocampus (Amruthesh et al., 1993) and from the cortex (Shivachar et al., 1995). The immunoreactivity of a polyclonal serum against human sEH with a protein band corresponding to ~62 kDa molecular mass and mobility similar to that of the purified human sEH positive control, suggests that astrocytes do express the sEH protein. Enrichment in the density of the 62 KDa proteins, and a ~3.6-fold increase in the enzyme activity in the 105,000×g supernatant (soluble fraction) over the cell lysate, suggest its cytosolic localization in astrocytes. These findings are consistent with the previous studies showing the expression of sEH in rat epididymus (DeTeaux et al., 2004) and in an array of human tissues (Enayetallah et al., 2005).

Addition to the cytosolic location of sEH, merging of GFAP and sEH images show a non-merged location for sEH, specifically in the nucleus suggesting nuclear localization, in addition to the cyctoplasm. Furthermore, merging of sEH stained cells with DAPI, which specifically stains nuclei blue, produced a bright purple color suggesting the nuclear colocalization. This was further supported by the double labeling mEH and sEH studies, which clearly showed nuclear localization of sEH.

Our immunocytochemical double staining data suggest that mEH was co-expressed along with GFAP, a cytoskeletal protein marker specific for astrocytes. Our western blot results suggest that the mEH protein band, with molecular mass corresponding to ~49–50kDa, is consistent with a protein identified as mEH in glioma cells (Kessler et al., 2000). Merging of fluorescence images showed a diffused staining pattern, characteristic of its cytoplasmic presence in astrocytes. This is in close agreement with the immunohistological and immunocytochemical studies of Enayetallah et al (2005) wherein they have shown a diffused distribution of mEH in the cell cytoplasm mainly in the membranes of endoplasmic reticulum and to some extent in the plasma membrane. Consistent with this, our immunocytochemical staining data show that expression of mEH was more concentrated around the outer surface of the nucleus and was more diffused towards the margins of the cell cytoplasm. However there was a slight enrichment in the enzyme activity in the microsomal fraction in contrast to the 3.6-fold enrichment in sEH activity in the soluble fraction. Since the mEH activity was assayed using the mEH-selective substrate cSO at pH 9.0, we believe the activity is selective for mEH. Furthermore, in our preparation, the microsomal fraction represents the 105,00×g pellet containing the membrane; it is possible that the mEH may have dislodged from the membrane during subcellular fractionation steps and extensive washing procedure resulting in a loss of protein and activity. The sEH, on the other hand, is shown to be localized mainly in the peroxisomes and lysosomes and appears more “punctate” or granular form (Enayetallah et al., 2005; 2006).

Interestingly, nuclear localization of other drug metabolizing enzymes, such as GST has recently been reported (Stella et al, 2007), wherein a significant amount of alpha GST is found to be electrostatistically associated with the nuclear membrane, our immunocytochemical detection of sEH in the nucleus may not be mere electrostatic association, as the subcellular fractions were extensively washed with 0.32M sucrose buffer as previously described (Pacifici et al. 1988). Although, the role of sEH in the nucleus remains unclear, it is conceivable to speculate that sEH may protect the DNA from the destructive action of reactive epoxides of drugs and endogenous epoxides originated as a result of cytochrome P450 metabolism of arachidonic acid (Shivachar et al., 1995). The presence of sEH in the nucleus is particularly important because astrocytes and neurons are vulnerable to damage by toxic epoxides or their precursor xenobiotics that may pass the blood-brain barrier. Furthermore, pathological oxidative metabolism can generate endogenous epoxides which are typically unstable and chemically reactive. In the human brain, EH activity has been shown to be six to ten times higher than in rat brain (Ghersi-Egea et al., 1993). The interception of potentially noxious compounds to prevent DNA damage could be a possible physiological role of the perinuclear and intranuclear localization of EHs.

Another possible site for EH distribution around the nucleus may be the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Various studies have reported impairment of ER function in the brain diseases including cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases (Paschen and Frandsen, 2001). These findings raise the possibility of sEH and mEH presence in ER, in ER -related brain disorders. Consistent with this, changes in the expression of EHs in astrocytes is seen in case of brain tumors (Kessler et al., 2000), and in the pathologic process of the Alzheimer’s disease (Liu et al., 2006). The expression of EHs in normal rat brain cortical astrocytes might play an important role in brain disorders involving trauma, genetic disorders, chemical insults, and infection /inflammation or epileptic seizures. Involvement of sEH in neuronal survival is evident from a recent study linking human sEH gene EPHX2 to neuronal survival after ischemic injury (Koerner et.al. 2007). However further studies are needed to provide insight into any compartment-specific role for sEH in brain diseases. Thus our study prompts the need for a careful investigation and characterization of endogenous expression of mEH /sEH in other brain cell types, including neurons in various brain areas and holds promise for furthering our understanding of interindividual variability of EHs in response to centrally acting drugs as well as for neurological diseases and pathologies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Texas Southern University graduate program for providing support to cover the cost of this publication. We also thank Kasturi Ranganna, Molecular Biology and Tissue Engineering Core facility, for assistance with fluorescence microscopy.

This study was supported by the grants from National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) –Research Centers for Minority Institutions (RCMI; G12-RR03045 to ACS; Program Director is Barbara E. Hayes) and National Institute of Environmental Safety (NIEHS; R37-ES02710 to BDH).

REFERENCES

- Amruthesh SC, Boerschel MF, Mckinney JS, Willoughby KA, Ellis EF. Metabolism of Arachidonic Acid to Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids, Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acids, and Prostaglandins in Cultured Rat Hippocampal Astrocytes. J.Neurochem. 1993;61:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arand M, Cronin A, Adamska M, Oesch F. Epoxide Hydrolases: Structure, Function, Mechanism, and Assay. In. Methods in Enzymol. 2005;400:569–588. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhan B, Mebrahtu T, Nazarian S, Kurth MJ, Hammock BD. Improved radiolabeled substrates for soluble epoxide hydrolase. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:188–200. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Harris RC. Cytochrome P450 and arachidonic acid bioactivation. Molecular and functional properties of the arachidonate monooxygenase. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacos N, Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Manna S, Martin-Wixtrom C, Gill SS, Hammock BD, Estabrook RW. The reaction of arachidonic acid epoxides (epoxyeicosatrienoic acids) with cytosolic epoxide hydrolase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1983;233:639–648. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuny G, Siest G, Minn A. Subcellular localization of cytochrome P-450, and activities of several enzymes responsible for drug metabolism in the human brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;45:647–658. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90139-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBiasio KW, Silva MH, Shull LR, Overstreet JW, Hammock BD, Miller MG. Xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme e activities in rat, mouse, monkey, and human testes. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 1991;19:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper AJ, Hammock BD. Soluble Epoxide hydrolase in rat inflammatory cells is indistinguishable from soluble epoxide hydrolase in rat liver. Toxicol.Sci. 1999;50:30–35. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/50.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuTeaux SB, Newmann JW, Morisseau C, Fairbairn EA, Jelks K, Hammock BD, Miller MG. Epoxide Hydrolases in rat epididymus: Possible Roles in Xenobiotic and Endogenous Fatty Acid Metabolism. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;78:187–194. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis EF, Police RJ, Yancey L, McKinney JS, Amruthesh SC. Dilation of cerebral arterioles by cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1990;259:H1171–H1177. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enayetallah AE, French RA, Thibodeau MS, Grant DF. Distribution of soluble epoxide hydrolase and of cytochrome P450 2C8:2C9, and 2J2 in human tissues. J Histochem. Cytochem. 2004;52(4):447–454. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enayetallah AE, French RA, Barber M, Grant DF. Cell specific subcellular localization of soluble epoxide hydrolase in human tissues. J. Histochem.Cytochem. 2005;54:329–335. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6808.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enayetallah AE, French RA, Barber M, Grant DF. Cell-specific subcellular localization of soluble epoxide hydrolase in human tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2006;54(3):329–335. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6808.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghersi-Egea JF, Leininger-Muller B, Suleman G, Siest G, Minn A. Localization of Drug-metabolizing enzyme activities to blood-brain interfaces and circumventricular organs. J.Neurochem. 1994;62:1089–1096. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Ota K, Hammock BD. Radiometric assays for mammalian epoxide hydrolases and glutathione S-transferase. Anal. Biochem. 1983;131:273–282. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP. Cytochrome P450 oxidations in the generation of reactive electrophiles: Epoxidation and related reactions. Arch. Biochem.Biophys. 2003;409:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick AM, Fahl WE. Mammalian Glutathione S-Transferase: Regulation of an Enzyme System to achieve chemotherapeutic efficacy. Pharmac. Ther. 1995;66:237–257. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00079-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock BD, Ota K. Differential induction of cytosolic epoxide hydrolase, microsomal epoxide hydrolase, and glutathine S-transferase activities. Toxicol.Appl. Pharmacol. 1983;71:254–265. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(83)90342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Zhao X, Capdevila JH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition lowers arterial blood pressure in angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:690–694. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung O, Brandes RP, Kim IH, Schweda F, Schmidt R, Hammock BD, Busse R, Fleming I. Soluble Epoxide hydrolase is a main effector of Angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:759–765. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153792.29478.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Hamou MF, Albertoni M, Tribolet ND, Arand M, Meir EGV. Identification of the Putative Brain Tumor Antigen BE7/GE2 as the (De) Toxifying Enzyme Microsomal Epoxide Hydrolase. Cancer Research. 2000;60:1403–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner IP, Jacks R, DeBarber AE, Koop D, Mao P, Grant DF, Alkayed NJ. Polymorphism in the human soluble epoxide hydrolase gene EPHX2 linked to neuronal survival after ischemic injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4642–4649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0056-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Sun A, Shin EJ, Liu X, Kim SG, Runyons CR, Markesbery W, Kim HC, Bing G. Expression of microsomal epoxide hydrolase is elevated in Alzheimer’s hippocampus and induced by exogenous β-amyloid and trimethyl-tin. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2027–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu AY, Miwa GT. Molecular properties and biological functions of microsomal epoxide hydrolse. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1980;20:513–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn A, Ghersi-Egea JF, Perrin R, Leininger B, Siest G. Drug metabolizing enzyme in the brain and cerebral microvessels. Brain.Res.Rev. 1991;16:65–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody DE, Silva MH, Hammock BD. Epoxide hydrolysis in the cytosol of rat liver, kidney, and testis. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1986;35:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Epoxide hydrolases: mechanisms, inhibitor designs, and biological roles. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:311–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. Antiinflammatory properties of Cytochrome P450 epooxygenase –derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285:1276–7279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W, Frandsen A. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction--a common denominator for cell injury in acute and degenerative diseases of the brain? J Neurochem. 2001;79(4):719–725. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici GM, Eriksson LC, Glaumann H, Rane A. Profile of drug Metabolizing Enzymes in the nuclear and microsomal fractions from rat liver nodules and normal liver. Arch.Toxicol. 1988;62:336–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00293619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranath V, Bhamre S, Bhagwat SV, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Shankar SK, Tirumalai PS. Xenobiotic metabolism in brain. Toxico. Lett. 1995;82–83:633–638. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilter B, Omiecinski CJ. Regional Distribution and Expression Modulation of Cytochrome P-450 and Epoxide Hydrolase mRNAs in the Rat Brain. Mol.Pharmacol. 1993;44:990–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeltzer KR, Kubala L, Newman JW, Kim IH, Eiserich, Hammock BD. Soluble Epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute Inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. 2005;102:9772–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503279102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivachar AC, Willoughby KA, Ellis EF. Effect of Protein Kinase C Modulators on 14, 15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid Incorporation into Astroglial Phospholipids. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:338–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivachar AC. Cannabinoid inhibition of sodium-dependent, high-affinity excitatory amino acid transport in cultured rat cortical astrocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;73:2004–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella L, Pallottini V, Moreno S, Leoni S, DeMaria F, Turella P, Federici G, Fabrini R, Dawood KF, Bello ML, Pedersen JZ, Ricci G. Electrostatic association of glutathione transferase to the nuclear membrane: Evidence of an Enzyme Defense Barrier at the Nuclear Envelope. J.Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6372–6379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Meijer J, Guengerich FP. Purification of human liver cytosolic epoxide hydrolase and comparison to the microsomal enzyme. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5769–5776. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wixtrom RN, Hammock BD. Membrane bound and soluble fraction epoxide hydrolases: Methodological Aspects. In: Zakim D, Vessey DA, editors. Biochemical Pharmacology and Toxicology Vol. 1: Methodological aspects of drug metabolizing enzymes. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1985. pp. 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yamamoto T, Newman JW, Kim IH, Watanabe T, Hammock BD, Stewart J, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Imig JD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition protects the kidney from hypertension-induced damage. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;15(5):1244–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Koerner IP, Noppens R, Grafe M, Tsai HJ, Morisseau C, Luria A, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Alkayed NJ. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: a novel therapeutic target in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1931–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]