Abstract

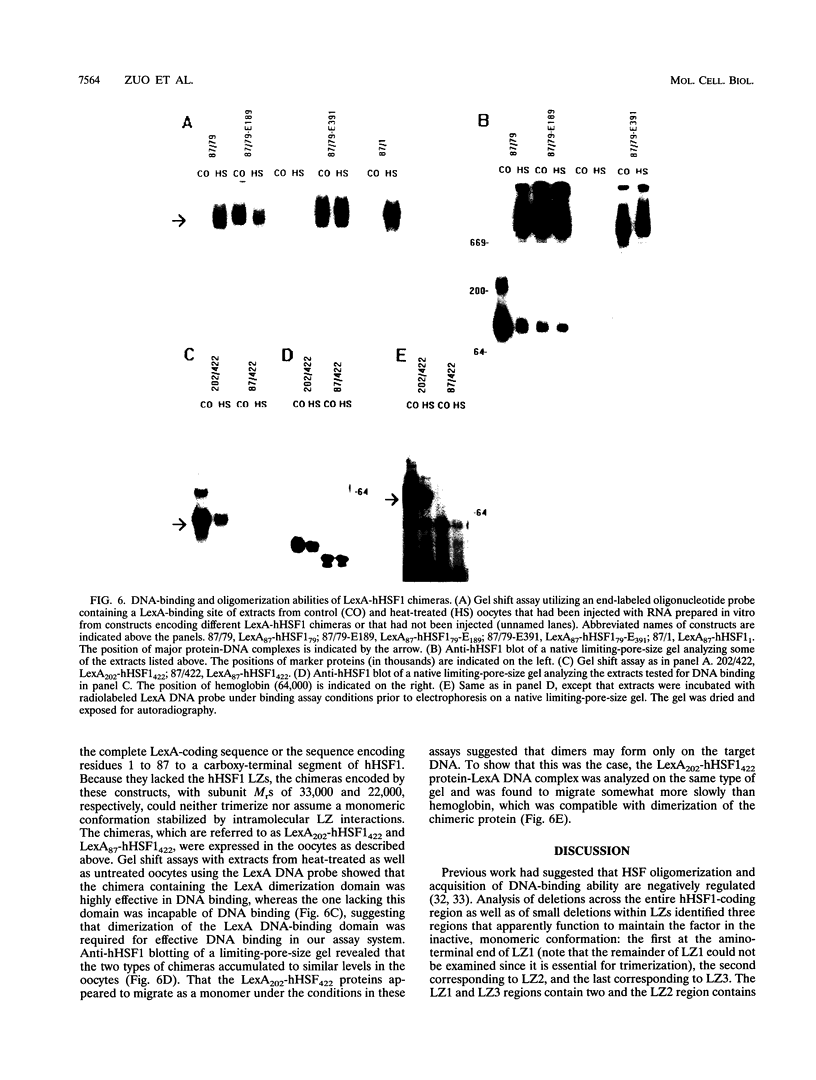

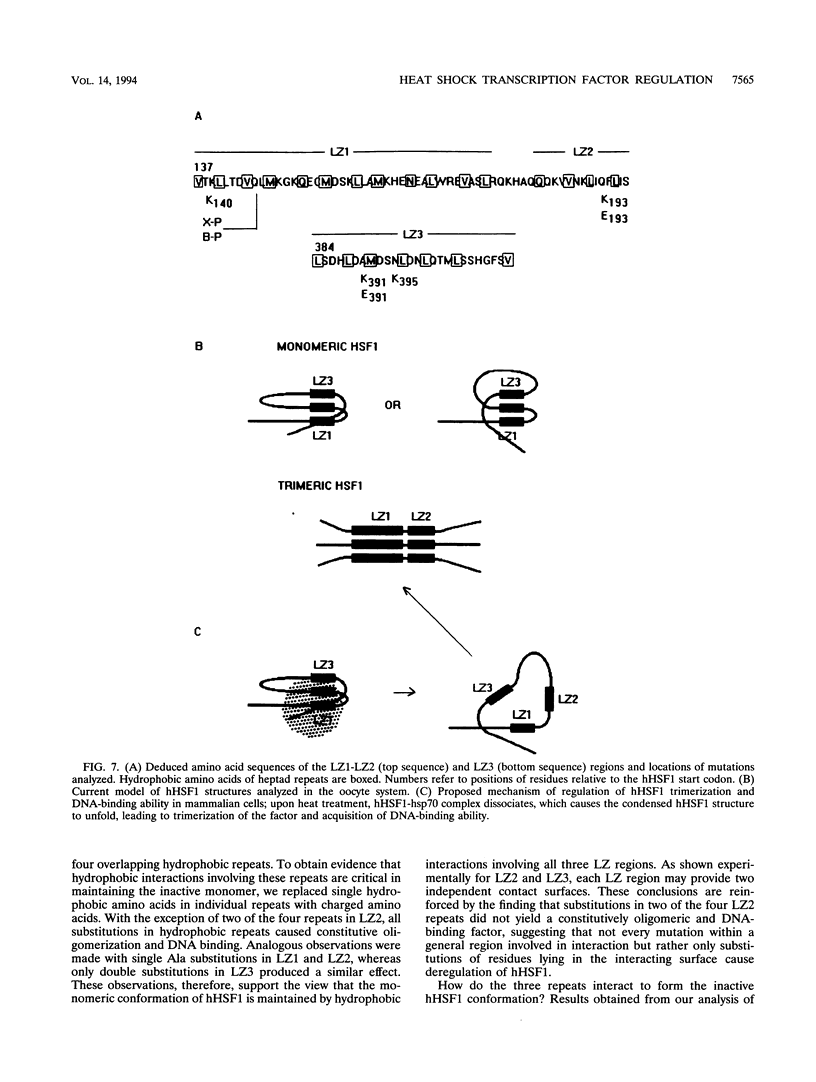

Heat stress regulation of human heat shock genes is mediated by human heat shock transcription factor hHSF1, which contains three 4-3 hydrophobic repeats (LZ1 to LZ3). In unstressed human cells (37 degrees C), hHSF1 appears to be in an inactive, monomeric state that may be maintained through intramolecular interactions stabilized by transient interaction with hsp70. Heat stress (39 to 42 degrees C) disrupts these interactions, and hHSF1 homotrimerizes and acquires heat shock element DNA-binding ability. hHSF1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes also assumes a monomeric, non-DNA-binding state and is converted to a trimeric, DNA-binding form upon exposure of the oocytes to heat shock (35 to 37 degrees C in this organism). Because endogenous HSF DNA-binding activity is low and anti-hHSF1 antibody does not recognize Xenopus HSF, we employed this system for mapping regions in hHSF1 that are required for the maintenance of the monomeric state. The results of mutagenesis analyses strongly suggest that the inactive hHSF1 monomer is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions involving all three leucine zippers which may form a triple-stranded coiled coil. Trimerization may enable the DNA-binding function of hHSF1 by facilitating cooperative binding of monomeric DNA-binding domains to the heat shock element motif. This view is supported by observations that several different LexA DNA-binding domain-hHSF1 chimeras bind to a LexA-binding site in a heat-regulated fashion, that single amino acid replacements disrupting the integrity of hydrophobic repeats render these chimeras constitutively trimeric and DNA binding, and that LexA itself binds stably to DNA only as a dimer but not as a monomer in our assays.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abravaya K., Myers M. P., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev. 1992 Jul;6(7):1153–1164. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J., Ananthan J., Voellmy R. Key features of heat shock regulatory elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Sep;8(9):3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J., Mestril R., Lawson R., Klapper H., Voellmy R. The heat shock consensus sequence is not sufficient for hsp70 gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Jan;5(1):197–203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthan J., Goldberg A. L., Voellmy R. Abnormal proteins serve as eukaryotic stress signals and trigger the activation of heat shock genes. Science. 1986 Apr 25;232(4749):522–524. doi: 10.1126/science.3083508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler R., Dahl G., Voellmy R. Activation of human heat shock genes is accompanied by oligomerization, modification, and rapid translocation of heat shock transcription factor HSF1. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Apr;13(4):2486–2496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler R., Welch W. J., Voellmy R. Heat shock gene regulation by nascent polypeptides and denatured proteins: hsp70 as a potential autoregulatory factor. J Cell Biol. 1992 Jun;117(6):1151–1159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann R. P., Mizzen L. E., Welch W. J. Interaction of Hsp 70 with newly synthesized proteins: implications for protein folding and assembly. Science. 1990 May 18;248(4957):850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.2188360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr C. M., Kim P. S. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell. 1993 May 21;73(4):823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clos J., Rabindran S., Wisniewski J., Wu C. Induction temperature of human heat shock factor is reprogrammed in a Drosophila cell environment. Nature. 1993 Jul 15;364(6434):252–255. doi: 10.1038/364252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clos J., Westwood J. T., Becker P. B., Wilson S., Lambert K., Wu C. Molecular cloning and expression of a hexameric Drosophila heat shock factor subject to negative regulation. Cell. 1990 Nov 30;63(5):1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90511-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland C. S., Doms R. W., Bolzau E. M., Webster R. G., Helenius A. Assembly of influenza hemagglutinin trimers and its role in intracellular transport. J Cell Biol. 1986 Oct;103(4):1179–1191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDomenico B. J., Bugaisky G. E., Lindquist S. The heat shock response is self-regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Cell. 1982 Dec;31(3 Pt 2):593–603. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberger T. E., Brandl C. J., Struhl K., Harrison S. C. The GCN4 basic region leucine zipper binds DNA as a dimer of uninterrupted alpha helices: crystal structure of the protein-DNA complex. Cell. 1992 Dec 24;71(7):1223–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn G. C., Chappell T. G., Rothman J. E. Peptide binding and release by proteins implicated as catalysts of protein assembly. Science. 1989 Jul 28;245(4916):385–390. doi: 10.1126/science.2756425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M. J., McCammon K., Sambrook J. Expression of wild-type and mutant forms of influenza hemagglutinin: the role of folding in intracellular transport. Cell. 1986 Sep 12;46(6):939–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C. J., Bohm A. A., Nelson H. C. Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the heat shock transcription factor. Science. 1994 Jan 14;263(5144):224–227. doi: 10.1126/science.8284672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower L. E. Cultured animal cells exposed to amino acid analogues or puromycin rapidly synthesize several polypeptides. J Cell Physiol. 1980 Mar;102(3):407–427. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges R. S., Saund A. K., Chong P. C., St-Pierre S. A., Reid R. E. Synthetic model for two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coils. Design, synthesis, and characterization of an 86-residue analog of tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 1981 Feb 10;256(3):1214–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P. M., Schlesinger M. J. The effect of amino acid analogues and heat shock on gene expression in chicken embryo fibroblasts. Cell. 1978 Dec;15(4):1277–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R. E., Schuetz T. J., Larin Z. Heat-inducible human factor that binds to a human hsp70 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Apr;7(4):1530–1534. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy B., Choe S., Cascio D., McRorie D. K., DeGrado W. F., Eisenberg D. Crystal structure of a synthetic triple-stranded alpha-helical bundle. Science. 1993 Feb 26;259(5099):1288–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.8446897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan A. D., Stewart M. Tropomyosin coiled-coil interactions: evidence for an unstaggered structure. J Mol Biol. 1975 Oct 25;98(2):293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea E. K., Klemm J. D., Kim P. S., Alber T. X-ray structure of the GCN4 leucine zipper, a two-stranded, parallel coiled coil. Science. 1991 Oct 25;254(5031):539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1948029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleros D. R., Welch W. J., Fink A. L. Interaction of hsp70 with unfolded proteins: effects of temperature and nucleotides on the kinetics of binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jul 1;88(13):5719–5723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. A regulatory upstream promoter element in the Drosophila hsp 70 heat-shock gene. Cell. 1982 Sep;30(2):517–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R. Speculations on the functions of the major heat shock and glucose-regulated proteins. Cell. 1986 Sep 26;46(7):959–961. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perisic O., Xiao H., Lis J. T. Stable binding of Drosophila heat shock factor to head-to-head and tail-to-tail repeats of a conserved 5 bp recognition unit. Cell. 1989 Dec 1;59(5):797–806. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peteranderl R., Nelson H. C. Trimerization of the heat shock transcription factor by a triple-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coil. Biochemistry. 1992 Dec 8;31(48):12272–12276. doi: 10.1021/bi00163a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price B. D., Calderwood S. K. Ca2+ is essential for multistep activation of the heat shock factor in permeabilized cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Jun;11(6):3365–3368. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran S. K., Giorgi G., Clos J., Wu C. Molecular cloning and expression of a human heat shock factor, HSF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Aug 15;88(16):6906–6910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran S. K., Haroun R. I., Clos J., Wisniewski J., Wu C. Regulation of heat shock factor trimer formation: role of a conserved leucine zipper. Science. 1993 Jan 8;259(5092):230–234. doi: 10.1126/science.8421783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarge K. D., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Mar;13(3):1392–1407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz T. J., Gallo G. J., Sheldon L., Tempst P., Kingston R. E. Isolation of a cDNA for HSF2: evidence for two heat shock factor genes in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Aug 15;88(16):6911–6915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon L. A., Kingston R. E. Hydrophobic coiled-coil domains regulate the subcellular localization of human heat shock factor 2. Genes Dev. 1993 Aug;7(8):1549–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Lewis M. J., Pelham H. R. Heat shock factor is regulated differently in yeast and HeLa cells. Nature. 1987 Sep 3;329(6134):81–84. doi: 10.1038/329081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Nelson H. C. Trimerization of a yeast transcriptional activator via a coiled-coil motif. Cell. 1989 Dec 1;59(5):807–813. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Pelham H. R. Purification and characterization of a heat-shock element binding protein from yeast. EMBO J. 1987 Oct;6(10):3035–3041. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. E., Craig E. A. Self-regulation of 70-kilodalton heat shock proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Apr;10(4):1622–1632. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voellmy R., Rungger D. Transcription of a Drosophila heat shock gene is heat-induced in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):1776–1780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood J. T., Clos J., Wu C. Stress-induced oligomerization and chromosomal relocalization of heat-shock factor. Nature. 1991 Oct 31;353(6347):822–827. doi: 10.1038/353822a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood J. T., Wu C. Activation of Drosophila heat shock factor: conformational change associated with a monomer-to-trimer transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Jun;13(6):3481–3486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G., Seto D., Parker C. S. Isolation of the gene encoding the S. cerevisiae heat shock transcription factor. Cell. 1988 Sep 9;54(6):841–853. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Lis J. T. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science. 1988 Mar 4;239(4844):1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.3125608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimarino V., Tsai C., Wu C. Complex modes of heat shock factor activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Feb;10(2):752–759. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]