To the Editor

One of the potential etiologies of the recent rise in allergic diseases is changes in environmental exposures such as dietary factors like folic acid. In a mouse model, a maternal dietary supplementation with methyl donors that included folic acid was related to severe allergic lung disease in the offspring.1 These animal model data have been supported by several epidemiologic studies that have found an increased risk of wheezing and lower respiratory tract infections from birth to 18 months of age2,3 and an increased risk of asthma4 associated with maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. In contrast to these studies, more recent studies showed no association between maternal folate supplementation and the risk of allergic diseases in the offspring.5,6

In contrast, in the NHANES, folate status was not a risk factor for allergic outcomes and, in fact, was inversely associated with atopy, wheeze, and elevated IgE levels.7 This latter study demonstrated an inverse relationship between folate and allergic disease as opposed to the positive relationship shown in the studies of in utero effects of folate, suggesting that folate’s effects may differ by age. Although a picture may be emerging that folate levels are associated with increased risk in utero but protection during late childhood and adulthood, the effects of folate in early childhood remain unknown. This question has important implications because intervening in early childhood, rather than pregnancy, by modifying folate intake would preserve the known beneficial effects of folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on the risk of neural tube defects. Therefore, we examined the effects of early childhood folate status on incident aeroallergen and food sensitization, as well as wheezing at school age, in a high-risk birth cohort.

We used data generated from the Childhood Origins of Asthma project, which is a cohort of children at high risk of developing asthma and allergic disease. Details about the study design and characteristics of its subjects (Table I) have been previously published. The Human Subjects Committee of the University of Wisconsin approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from the parents. Outcomes of interest included wheezing, asthma diagnosis, and allergic sensitization. For more details, please refer to the Appendix in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

TABLE I.

Sociodemographic characteristics

| Characteristic | % (n = 138) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 58 |

| Female | 42 |

| Age, mean ± SE | |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 88 |

| Hispanic | 4 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5 |

| Other | 2 |

| Maternal asthma | 43 |

| Paternal asthma | 28 |

| Maternal allergy | 85 |

| Paternal allergy | 79 |

| Income ($) | |

| <20,000 | 4 |

| ≥20,000 | 83 |

| Refused/don’t know | 13 |

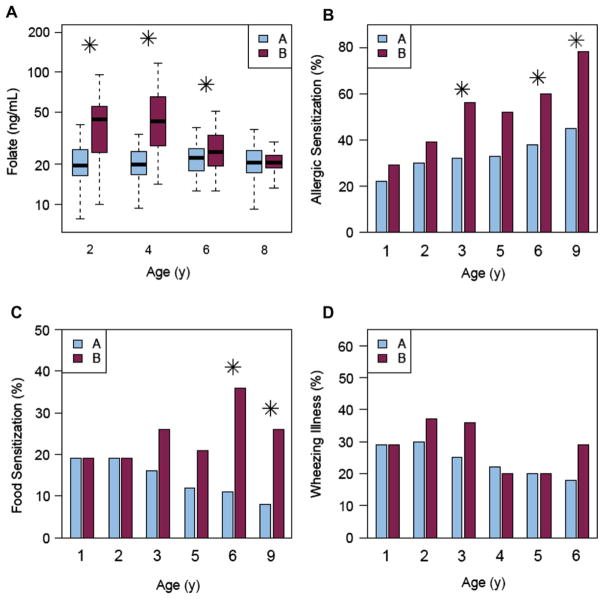

Folate levels were measured in our cohort (n = 138) at ages 2, 4, 6, and 8 years, and model-based clustering (please see References in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org) was used to identify 2 clusters of participants on the basis of the temporal pattern of their folate levels. Cluster A, comprising 75% of the cohort, had stable levels throughout the first 8 years, while cluster B, the remaining 25% of the cohort, initially had higher folate levels but by year 8 was no different than cluster A (Fig 1, A). Cluster B had significantly greater rates of allergen sensitization at ages 3 (P =.03), 6 (P =.05), and 9 years (P =.008) (Fig 1, B). Specifically, cluster B had higher rates of sensitization to seasonal aeroallergens (21% vs 44%; P =.03), perennial aeroallergens (41% vs 68%; P =.02), and foods (8% vs 26%; P =.02) (Fig 1, B and C).

FIG 1.

A, Model-based clustering identification of 2 clusters of participants on the basis of the temporal pattern of their folate levels. Cluster A shown in blue and cluster B shown in red. B, Rates of allergen sensitization in cluster A versus cluster B. C, Rates of food sensitization in cluster A versus cluster B. D, Wheezing illness in cluster A versus cluster B.

These relationships remained significant after adjusting for gender and socioeconomic status. Interestingly, total IgE levels did not differ significantly by folate cluster (data not shown), suggesting that early-life folate status may influence the risk of specific allergic sensitization rather than IgE production in general. In addition, wheezing illness (Fig 1, D) and asthma rates at 6 years (36% vs 39%; P =.74) did not differ between the 2 folate clusters, respectively. Last, a comparison of the characteristics of the children who were included versus those who were excluded from the Childhood Origins of Asthma cohort showed no significant differences (see Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to find that early-life folate status may influence the risk of incident aeroallergen and food sensitization. In addition, our findings suggest that the first few years of life, a critical time period for immune maturation, may be an age at which children may be more vulnerable to potential immune-modulating effects of folate. Our results also support the notion that the effects of folate vary by age. Specifically, higher folate levels in utero and early childhood folate status may increase the risk of allergic sensitization while higher folate levels later in life may confer protection against allergic sensitization.7

Although we observed associations between folate status and allergic sensitization, there were no significant associations between folate status and wheeze or asthma. While it is plausible that folate acts mainly on allergic sensitization, and does not affect the risk of respiratory allergy, the modest sample size of this cohort limits our statistical power to detect effect sizes that might be expected with an outcome such as wheeze. Future studies powered to detect this magnitude of effect are needed before a relationship between early-life folate levels and asthma risk can be ruled out.

Another novel aspect of our findings was that the risk of aeroallergen sensitization associated with higher early-life folate levels was also observed for food sensitization. Higher folate levels were associated with an increased risk of developing any food sensitization to milk, egg, or peanut. Although differences in food sensitization rates were first observed at age 3 years, these differences between the 2 folate groups were not statistically significant until age 6 years. Because of the modest sample size, we were unable to determine whether the risk of food sensitization was also borne out as an increased risk in likely food allergy.

The mechanisms underlying our observations are unclear. Although folate has a myriad of biologic effects, one current hypothesis posits that it may promote DNA methylation since it serves as a methyl donor, thereby suppressing the expression of key immune regulatory genes.1,8 Although these findings point to the potential for folate to act via an epigenetic mechanism in early childhood, folate has many roles in cellular function so that it may act on the pathogenesis of allergic sensitization by other mechanisms.

Other potential confounding factors may include breast-feeding, consumption of high-folate-containing (or folate-fortified) foods. In this study, we found no significant difference between breast-feeding in both clusters (data not shown). Although we cannot ascertain exactly what role diet may have contributed to variability in our findings, in this study dietary folic acid intake would not be considered a true confounder as it is present in the causal pathway; since dietary intake is the major driver of plasma folate levels, our use of plasma folate levels already captures the dietary intake of folic acid. However, it is possible that plasma folate levels are simply a marker in general of a healthy diet and that some other component of a healthy diet—such as another micronutrient—could be the true driver of allergic sensitization risk rather than folate. The observational study design does not allow for the evaluation of this question, and so this limitation could not be controlled for in a natural history study such as Childhood Origins of Asthma.

In summary, we found in a high-risk birth cohort that higher folate levels in early childhood were significantly associated with the increased incidence of both food and aeroallergen sensitization, suggesting that folate may confer the risk of allergy not only in utero but also in the first few years of life. These findings suggest that modification of folate intake in early childhood could reduce the risk of allergic sensitization and support the conduct of larger prospective studies to determine whether these findings are reproducible and whether folate affects the risk of allergic disease as well as the risk of allergic sensitization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants M01 RR03186, R01 HL61879, 1UL1RR025011, and P01 HL70831 5P50ES015903 P01 ES018176-5R01AI070630.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: R. F. Lemanske, Jr has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and Pharmaxis; has received consultancy fees from Merck, Sepracor, SA Boney and Associates, GlaxoSmithKline, American Institute of Research, Genentech, Double Helix Development, and Boehringer Ingelheim; is employed by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health; has received lecture fees from the Michigan Public Health Institute, Allegheny General Hospital, the American Academy of Pediatrics, West Allegheny Health Systems, California Chapter 4 AAP, the Colorado Allergy Society, the Pennsylvania Allergy and Asthma Association, Harvard Pilgrim Health, the California Society of Allergy, NYC Allergy Society, the World Allergy Organization, and the American College of Chest Physicians; has received payment for manuscript preparation from the AAAAI; and receives royalties from Elsevier and UpToDate. D. J. Jackson has received research support from the NIH, Pharmaxis, and AAAAI/GlaxoSmithKline and has received consultancy fees from Gilead. M. D. Evans has received research support from the NIH. R. A. Wood has received consultancy fees from the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America; is employed by Johns Hopkins University; has provided expert testimony for the NIH; and receives royalties from UpToDate. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Boon K, Garantziotis S, Li Z, Tomfohr J, et al. In utero supplementation with methyl donors enhances allergic airway disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3462–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI34378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Haberg SE, London SD, Stigum H, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:180–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.142448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haberg SE, London SJ, Nafstad P, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, et al. Maternal folate levels in pregnancy and asthma in children at age 3 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:262–4. 264.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1486–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magdelijns FJ, Mommers M, Penders J, Smits L, Thijs C. Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e135–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekkers MB, Elstgeest LE, Scholtens S, Haveman A, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, et al. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and childhood respiratory health and atopy: the PIAMA birth cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1468–74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00094511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsui EC, Matsui W. Higher serum folate levels are associated with a lower risk of atopy and wheeze. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1253–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadeau K, McDonald-Hyman C, Noth EM, Pratt B, Hammond SK, Balmes J, et al. Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:845–852.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.