Abstract

In patients with congenital heart disease, the right heart may support the pulmonary or the systemic circulation. Several congenital heart diseases primarily affect the right heart including Tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of great arteries, septal defects leading to pulmonary vascular disease, Ebstein anomaly and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. In these patients, right ventricular dysfunction leads to considerable morbidity and mortality. In this paper, our objective is to review the mechanisms and management of right heart failure associated with congenital heart disease. We will outline pearls and pitfalls in the management of congenital heart disease affecting the right heart and highlight recent advances in the field.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, Right heart

Introduction

Over the past five decades, major advances have been made in both diagnosis and management of congenital heart disease (CHD). Despite having complex congenital heart disease, the majority of children are now surviving into adulthood. The population of adults with CHD is estimated to grow by approximately 5% each year and the number of adults with CHD has now surpassed children with CHD [1].

In patients with CHD, the right ventricle (RV) may function as either the sub-pulmonary or the systemic ventricle as in transposition of great arteries (TGA). Among CHD more commonly affecting the right heart, we find atrial septal defects (ASD), Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), pulmonary stenosis (PS), Ebstein anomaly, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), and pulmonary valve atresia. In many of these patients, prevention of “irreversible” right heart failure (RHF) will require timely corrective surgery or when not possible, surgical palliation. In recent years, guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology help guide the management of patients CHD and right heart failure [2,3]. An excellent book on congenital diseases in the right heart has also been recently edited by Redington, Van Arsdell and Anderson.

In this paper, we will discuss the mechanisms and management of RHF in patients CHD. We will also highlight new development in the field as well as promising areas of research. We will not extensively discuss magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of CHD as this will be covered in a separate section of this special edition. We will also not cover right heart failure in the context of left heart disease.

Definition of Right Heart Failure in Patients with CHD

Right heart failure represents a complex clinical syndrome characterized by the inability of the right heart to sufficiently eject blood or fill at sufficiently low pressure to meet the needs of the body. In patients with CHD, both systolic and diastolic RV dysfunction often occurs. As the RV dilates, tricuspid regurgitation (TR) may also contribute to the heart failure syndrome. Cardiac arrhythmias may also be a prominent feature of patients with CHD and RHF especially in patients with previous ventriculotomy, patients with severe right atrial enlargement or in patients with ARVC [4,5]. As was shown by the study of Bolger et al., the syndrome of right heart failure in patients with CHD not only involves hemodynamic perturbation but also neurohormonal (e.g., B-type natriuretic perptide, atrial natriuretic peptide) and inflammatory activation (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α, cytokine) [6].

Selected CHD Affecting the Right Heart

Isolated septal defects are the most frequent cardiac congenital abnormalities after bicuspid aortic valve. Atrial septal defects (ASD) are most common septal defects encountered in adulthood. Ostium secundum defects account for 70% of all ASD. Sinus venosus ASD and ostium primum defect represent 5% and 10% of all ASD respectively [7]. It is now accepted that long-standing right heart volume overload and dilatation in the setting of an ASD is detrimental and leads to increased morbidity (heart failure, arrhythmia, and thromboembolic events) and mortality [7]. Overt congestive cardiac failure, or pulmonary vascular disease may develop in up to 5% to 10% of affected (mainly female) individuals [2]. Atrial arrhythmias associated with atrial and ventricular dilatation occur more commonly in older individuals.

Pulmonary valve stenosis is the main cause of congenital right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction occurring in 80% to 90% of cases. It represents 10% to 12% of all cases of CHD in adults [1]. Chronic right ventricular pressure overload (RVPO) often leads to adaptive remodeling of the RV characterized by ventricular hypertrophy without significant chamber enlargement. RV failure may occur in some patients with severe obstruction especially in patients with concomitant pulmonary regurgitation and often late in the course of the disease. In patients with increased intracardiac gradients, it is also important to exclude double chambered right ventricle (DCRV) which is due to aberrant hypertrophied muscular bands. DCRV is most often associated with ventricular septal defect (VSD) and the RV cavity is divided into a proximal high-pressure and a distal low-pressure chamber [8]. The obstruction usually resides below the RVOT and is commonly asymptomatic unless the obstruction is severe or when associated with a significant VSD [8,9].

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) has an incidence of 0.5 per 1000 live births. This is the most frequent cardiac complex malformation, accounting for 5% to 7% of all CHD [10]. Impaired cardiac progenitor cell migration and differentiation during development is involved in the pathogenesis of TOF [11]. Early palliative or corrective procedures are required in newborns. Since the first surgical correction attempted by Lillehei more than 50 years ago, operative mortality has significantly decreased [12]. RV function is commonly abnormal after TOF repair, especially when relief of obstruction of the outflow tract is associated with pulmonary valve regurgitation.

Ebstein anomaly is a complex congenital heart malformation, characterized by an apical displacement of both the septal and the posterior tricuspid leaflets, exceeding 20 mm or 8 mm/m2 [8]. Ebstein anomaly accounts for less than 1% of all cases of CHD in adults. It is commonly associated with other heart defects including ASD. Apical displacement of the tricuspid annulus may result in significant tricuspid regurgitation. Moreover, the atrialized portion of the RV may contribute to ventricular dysfunction. Equally important, patients with Ebstein anomaly may have accessory bypass tracts pathways and preexcitation pathways that often need to be addressed if symptomatic or when considering surgery.

Transposition of great arteries (TGA) accounts for 2.6% to 7.8% of all cases of CHD [13]. In congenitally corrected TGA (cc-TGA), there is both atrio-ventricular discordance and ventriculo-arterial discordance. The RV is connected in series with the left atrium and the aorta. Associated lesions are common in patients with cc-TGA and include VSD, PS and Ebstein anomaly of the systemic tricuspid valve [14]. In patients without associated lesions, survival is decreased as there is a propensity to complete heart block, TR, and the development of RV systolic dysfunction. As will be discussed, microvascular dysfunction also contributes to ventricular dysfunction in cc-TGA. In dextro-transposition of great arteries (d-TGA), there is ventriculo-arterial discordance and the anatomical RV is connected to the aorta and the pulmonary and systemic circulations function in parallel. Complete TGA is incompatible with life without a surgical switch of the circulation either at atrial or great arterial level. Currently, arterial switch is the surgical procedure of choice and restores ventriculo-arterial concordance. Surveillance of late coronary reimplantation is necessary to rule out stenosis or vascular complications. Atrial repair or venous switch operations, i.e. Senning or Mustard procedures, were the first successful interventions leading to long term survival of children with d-TGA. They created atrio-ventricular discordance which allowed the systemic and pulmonary circulations work in series but the right ventricle remained in systemic position. Most of d-TGA adults alive nowadays received one of these atrial switch procedures in childhood and are at a higher risk of late RV dysfunction, atrial arrhythmias, and tricuspid valve insufficiency [15-17]. Moons et al. reported actuarial survival at 10, 20 and 30 years of 91.7%, 88.6%, and 79.3% respectively [18].

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) also known as arrythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia is a myocardial disease characterized by loss of myocardial cells with replacement by fibrous and/or fatty tissue [18]. Although it preferentially affects the RV, it can present with biventricular failure. Ventricular tachyarrhythymias and sudden death are its most feared presentation [19]. The exact prevalence is not known but estimates of 1 in 5,000 cases appear to be conservative. Mutations in desmosomal proteins have been identified and appear to explain 30 to 40% of cases. Depending on the mutation, the mode of inheritance may be autosomal recessive or dominant [20]. RV involvement may include fatty infiltration of the RV, localized RV aneurysms and enlargement, or dysfunction of the RV. Task Force criteria addressing the diagnostic criteria have been developed. ARVC is more commonly seen in adulthood. It is uncommon in childhood and may be seen in older children and adolescents. Prevention of sudden death is most important therapeutic intervention to consider in patients with ARVC [21,22].

Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) associated with CHD belongs to group 1 of clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension [23]. Increased blood flow and pressure in the pulmonary vasculature result in endothelial dysfunction, proliferation, and hypertrophy of muscular cells. Associated vasoconstriction and plexiform lesions in small arteries give rise to increasing pulmonary vascular resistance. The prevalence of PAH in patients with CHD ranges between 1.7 and 12.8 cases per million adults [24,25]. Eisenmenger syndrome is characterized by the development of systemic pressures in the pulmonary circulation. This is a complex entity that can lead to a right to left blood shunting in case of persistent cardiac defect [26]. Compared to patients with idiopathic PAH, survival is better in patients with Eisenmenger physiology. Preservation of the fetal phenotype with equal right and left myocardial mass may explain why RV failure is delayed in Eisenmenger patients. Another hypothesis is that persistent septal defect provides a right to left shunting for blood flow in the presence of suprasystemic pulmonary vascular resistance [27-29].

Overview of the Mechanisms of Right Heart Failure in CHD

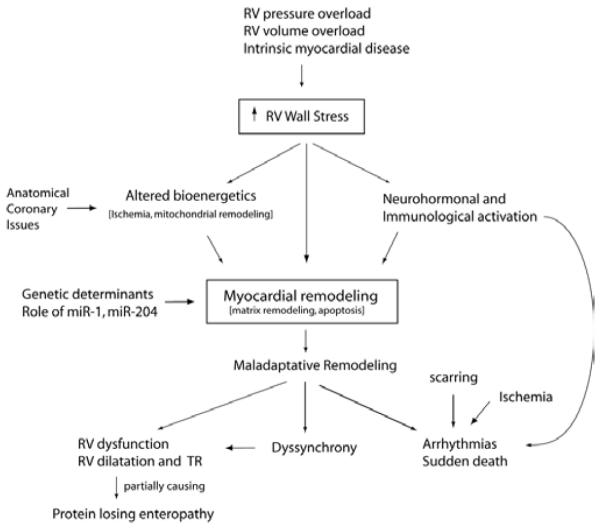

Depending of the specific CHD, several mechanisms may contribute to RHF in CHD including pressure or volume overload or intrinsic myocardial disease (Figure 1). Myocardial ischemia may also contribute to the progression of RV failure; this has been shown in patients with cc-TGA and d-TGA after atrial switch surgery [30-32]. In patients with CHD affecting the right heart, pressure and volume overload may combine to cause progressive RHF. This is often observed in patients with TOF who may have a combination of pulmonary stenosis and regurgitation or in patients with RVPO and progressive TR.

Figure 1.

General mechanisms contributing to RV failure in patients with CHD. Several mechanisms contribute to maladaptative RV remodeling in patients with CHD. The schematic does not take into account associated congenital heart defects that can contribute to the ventricular dysfunction. Please refer to text for further explanation.

In terms of compensation, the RV adapts much better to chronic volume overload than to pressure overload. Slower onset of RV overload as well as development of RV overload in childhood is also usually better tolerated. For example, patients with VSD and Eisenmenger physiology often show a better ventricular compensation than patients with later onset of PAH. Morphologically, patients with VSD and Eisenmenger physiology have thicker and smaller right ventricles. In a recent study, Bogaard et al. compared two experimental models of pulmonary hypertension, one with progressive RV pressure overload by pulmonary artery banding and the other with PAH induced by angioproliferative stimulus [33]. For the same level of ventricular afterload, severe RHF was seen in the second group whereas adaptive myocardial hypertrophy was observed in the banding group. They hypothesized that pulmonary vasculature is able to induce impaired right ventricular remodeling via the release of unidentified mediators [33].

Structural and Functional Remodeling in Patients with RHF and CHD

In response to pressure or volume overload, differences are noted in RV versus left ventricular remodeling. For example, in patients with left heart disease and pressure overload such as hypertension or aortic stenosis, the left ventricle (LV) thickens but rarely dilates. In contrast, patients with PAH that develops in late childhood often have enlarged RV and usually a decrease in RV ejection fraction (RVEF). In the presence of volume overload, the RV also significantly dilates. Atrial enlargement often occurs in RV volume overload states and has been associated with an increased risk of atrial tachyarrhythmias especially in patients with septal defects.

Functional impairments are also common in patients with CHD affecting the right heart. While patients with RV volume overload often have preserved RVEF, recent studies suggest abnormalities in ventricular contractility. Impairment in ventricular contractility was also suggested in patients with RVPO. In the study of Monreal et al., impairment in contraction and relaxation of RV cardiomyocytes were observed in a restrictive VSD experimental model [34]. Previous studies in animals and in adults with PAH have shown that right ventricular contractility measured by ventricular elastance is usually increased but often insufficient to compensate for the increase in afterload and ventriculo-arterial uncoupling which occurs [35]. With disease progression, the RV often dilates and ventricular function decreases further. TR may also lead to further chamber dilatation and progression of disease. Hypoplasic RV chamber may also contribute to ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Diastolic dysfunction has often been noted in patients with CHD affecting the right heart [8]. This often manifested by increased right atrial filling pressure, increased ventricular relaxation or restrictive filling patterns of the right ventricle. Diastolic characteristics of the RV may sometimes be difficult to assess in the presence of severe TR. In patients with TOF, restrictive filling profiles have been associated with prognosis [36,37]. RV restrictive filling pattern in TOF is characterized by the presence of late diastolic pulmonary flow. This occurs in a less compliant RV when end-diastolic RV pressure exceeds pulmonary pressures [36]. Restrictive filling profile in the RV has a different prognostic value depending if it occurs early or late post-operatively. Early post-operatively, a restrictive filling profile is associated with decreased stroke volume and increased post-operative complication [38]. Although the restrictive filling is a marker of worse outcome, it can be beneficial as it helps maintain forward flow and limits pulmonary regurgitation. Therefore, a restrictive filling pattern later in the course may confer a better prognostic value as a less compliant ventricle is protected from further enlargement in the presence of severe pulmonary regurgitation [39].

Ventricular interdependence is also more prominent in patients with right heart disease. The enlarged RV usually changes septal curvature as well as the shape and size of the LV. Severe enlargement of the RV especially when acute, also increases pericardial constrain and impairs LV filling. Physiologically, the LV can show impaired ventricular relaxation and occasionally a decrease in systolic phase indices of the LV such as left ventricular ejection fraction.

Histological and Molecular Remodeling of the Right Heart

In contrast to studies of left ventricular dysfunction, only a few studies have examined the cellular and molecular mechanisms of RV remodeling. In RV pressure overload states, apoptotic inducers such as Bax or transcriptional factor P53 are enhanced in RV myocardium early after experimental pulmonary artery banding [40]. Myocardial hypertrophy in response to chronic pressure overload has also been reported to induce cardiomyocyte death. Active caspase-3 protein level, a key protease of the main apoptotic pathway, is increased in thickened myocardium [41]. At a cellular level, marked down-regulation of the α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) was observed with a reciprocal upregulation of its less active β-isoform (β-MHC). Such shift in cardiac myosin composition is associated with a decrease in RV contractility and has been seen in other pathologic conditions associated with ventricular dysfunction and heart failure [42-44].

In terms of connective tissue remodeling, increased density of connective tissue within the myocardium had been found in experimental models of both volume and pressure overload [45,46]. Late fibrotic replacement of dead cardiomyocytes finally leads to irreversible cardiac failure. RV volume overload has also been associated with overexpression of several growth factors. Angiotensinogen, insulin-like growth factor-I, and preproendothelin-1 may be produced by cardiac fibroblasts in response to mechanical stress [47]. These specific fibroblasts regulate extracellular matrix regeneration and cardiomyocyte differentiation. They may play a key role in the adverse myocardial remodeling that occurs in heart failure [9]. Experimental studies suggest that cardiomyocytes hypertrophy and significant fibrosis can be associated with late impaired contractility [46]. Cytoskeletal remodeling may also induce right ventricular dysfunction via desmin protein upregulation [34].

More recent studies have described micro-RNAs as key regulators in patients with PAH. In the study of Bonnet et al., miR-204 has been implicated in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells proliferation and apoptosis in PAH [48]. Potential involvement of micro-RNAs has also been suggested in the development of CHD. Ikeda et al. have found that miR-1 regulates cardiomyocytes growth via calcium signaling inhibition [49]. Further studies are needed to demonstrate micro-RNAs implication in right heart remodeling in CHD affecting the right heart. It will be interesting to explore micro-RNA biology as a potential new therapy for RV diseases.

Systemic Consequences of the Right Heart Failure Syndrome

As mentioned previously, inflammation is an important part of RHF in CHD. This could contribute to the fatigue and cachexia that sometimes can accompany severe RHF. Cardiac cirrhosis may occasionally be observed in patients with persistent elevated right atrial pressure. Protein losing enteropathy is occasionally seen after the Fontan procedure or in patients with severe RV failure. Its etiology is multifactorial and cannot be simply explained by elevated right atrial pressure alone. This complex condition may lead to profound hypoproteinemia, malnutrition, and immunological deficiencies [50].

Assessment of the Right Heart

Several modalities are now available to allow comprehensive morphological and functional assessment of the RV. While echocardiography remains the mainstay of evaluation of the RV, MRI is emerging as the gold standard and provides essential structural information for planning surgery [8]. MRI allows assessment of RV structure, volumes, systolic and valvular function as well as myocardial perfusion. Morphological features that allow the recognition of the anatomical RV include the more apical insertion of the atrio-ventricular valve, the presence of the moderator band and the tricuspid morphology of the atrio-ventricular valve. Hemodynamic assessment allows accurate measurements of pulmonary and cardiac pressures as well as pulmonary vascular resistance and is especially in patients considered for corrective intervention or surgery.

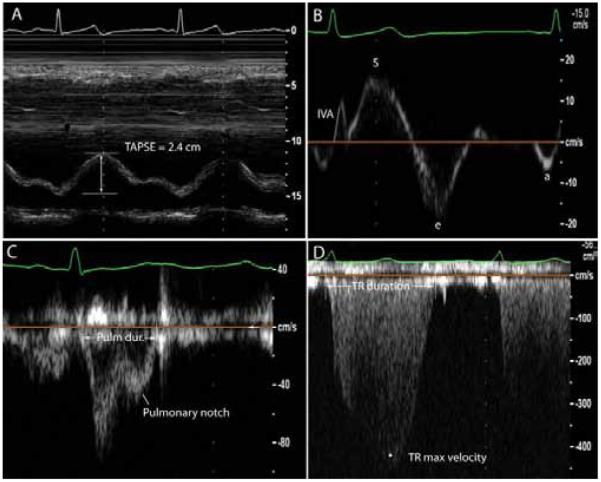

The most commonly used systolic phase indices are RVEF, RV fractional area change (assessed in the 4 chamber apical view by echocardiography), and the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE). In recent years, several functional indices of the RV have been described in the hope of providing either non-geometric or less load dependent indices of right ventricular function [5]. The rationale for using these more novel indices is that their relative load independence would make them better predictors of recovery. This has however yet to be established or well validated in large studies.

Right ventricular myocardial performance index (RVMPI) or the Tei index is a non-geometric index of ventricular function and is calculated as the ratio of isovolumic contraction and relaxation time divided by contraction time. While originally described as a more load independent index of ventricular contraction, studies have shown that RVMPI is also load dependent [51]. A more recent index that has been described by Vogel et al. is the myocardial acceleration of isovolumic contraction (IVA) that has been described as one of the more load independent indices of ventricular function [52-54]. It has been validated in patients with TOF and TGA and enthusiasm surrounds this novel measure. Normal values in humans still need to be better established however and superiority of IVA in predicting outcome still need to be proven. Figure 2 shows common measures of RV function, i.e. TAPSE, IVA, and pulmonary and tricuspid flow useful in the measure of the myocardial performance index. A pulmonary notch is also noted on the pulmonary flow signal which often indicates decreased pulmonary compliance.

Figure 2.

Selected echocardiographic signals and indices used to measure right ventricular function and pulmonary flow. Section A shows tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) in a patient with preserved RV systolic function. Section B shows a tissue-Doppler signal of the proximal right ventricular wall; isovolumic acceleration is measured as the maximal isovolumic velocity divided by the time to peak isovolumic velocity; e is the maximal early diastolic velocity and a represents the maximal late or atrial associated velocity. Section C shows a pulmonary flow signal; a notch is present and usually indicates decreased pulmonary compliance and altered reflection waves. Section D shows a tricuspid regurgitation signal. Both the pulmonary ejection time and the tricuspid regurgitation time are used to measure the right ventricular myocardial performance index (RVMPI).

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging is sometimes used to better assess perfusion and metabolism of the RV but especially in the research setting. Perfusion defects have been noted in d-TGA after Senning procedure and in patients with cc-TGA. In pulmonary arterial hypertension, although not necessarily a congenital disease, interesting studies have shown a decrease in glucose metabolism [55]. Table 1 summarizes some of pearls and pitfalls in managing patients with CHD and right heart failure.

Table 1.

Pearls and Pitfalls in managing in Managing CHD with Right Heart Failure.

| Pearls |

| – The RV is recognized by its morphological features and not by its location (e.g. in ccTGA, the RV is on the left) |

| – If a shunt is suspected and not demonstrated on TTE, pursue contrast imaging or magnetic resonance imaging |

| – Always assess coronary anatomy if a patient is deteriorating or before a corrective surgery e.g. in TOF or TGA post arterial switch |

| – Always exclude associated congenital heart defects |

| – Atrial arrhythmias or ventricular tachycardia often indicate severe hemodynamic compromise and should lead to further assessment |

| – Always consider protein losing enteropathy in the presence of hypoalbuminemia |

| – Close monitoring of patients with RV failure is needed to find the proper window for surgery (cf. table on indications) |

| Pitfalls |

| – Never attempt to close a septal defect in the presence of severe “irreversible” PH |

| – Never manage complex congenital cases without referral to a regional referral center of CHD |

| – Avoid maximal exercise testing in a patient with severe PH and RV failure (context of ASD or VSD) |

| – Avoid cardiac catheterization in patients with mild disease or if surgery is not planned. |

Management of CHD Affecting the RV: Lessons from the Guidelines

The key in managing RHF associated with CHD is finding the appropriate timing for corrective surgery. The ideal timing would allow for functional and structural recovery of the RV while minimizing surgical risk as well as the need for repeat surgeries such as repeated valvular replacements in the growing child. In cases when palliation is necessary, optimal timing of palliation will be necessary to avoid the prolonged systemic complications of RVF syndrome such as cardiac cachexia or protein losing enteropathy. Surgery should always be performed by surgeons trained in CHD surgery. Table 2 summarizes some of the recommendations for the recent guidelines by Warnes et al. about management of adults with CHD; this table is not intended to replace the guidelines but just as a focus overview of some of the key elements of the guidelines relative to CHD and RH failure. (ref15) Most of these recommendations are also valid for patients in childhood.

Table 2.

Management of selected CHD affecting the right heart*.

| CHD affecting the RV | Indication for intervention or medical therapy | Contraindication or pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial septal defects | Closure in the presence of: - right atrial or RV enlargement (I) - paradoxical embolism (IIa) - document orthodoxia or platypnea (IIa) - if tricuspid valve surgery planned (IIa) |

Patients with severe “irreversible” PH PAP > 2/3 systemic pressures PVR > 2/3 of SVR Failure occlusion test of defect |

| Ventricular septal defects | Closure if - Qp/Qs > 2 and signs of LV volume overload (I) -Qp/Qs > 1.5 and reversible PH (IIa) or LV systolic or diastolic dysfunction (IIa) -history of infective endocarditis (I) |

Patients with severe “irreversible” PH cf criteria above |

| RV outflow tract obstruction |

Balloon valvotomy for a domed valve if: -asymptomatic with peak Doppler PG > 60mmHg or mean PG > 40 mmHg and less than moderate PR (I) - symptomatic with peak Doppler PG > 50mmHg or mean PG > 30 mmHg (I) For a dysplasic valve, same criteria but (IIb) recommendation |

Balloon valvotomy not recommended if - peak Gradient by Doppler < 50 mmHg in the presence of normal - PS with severe PR - symptomatic patients with peak gradient < 30 mmHg. |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | Surgery for adults with previous repair of TOF - symptomatic severe PR (I) - severe PR with RV enlargement or dysfunction (IIa) - severe TR (IIa) - significant residual RVOT stenosis (IIa) - sustained arrhythmias (IIa) - residual VSD or severe AR (IIa) |

Always ascertain coronary anatomy before surgery Never forget to stratify the risk of sudden death in patients with TOF |

| Ebstein Anomaly | Tricuspid valve repair and closure ASD if - symptomatic (I) - cyanosis (I) - progressive RV dilatation or RV dysfunction (I) - paradoxial embolism (I) |

Always consider ventricular pre-excitation |

| ccTGA | Moderate or progressive AV valve regurgitation Refer to guidelines for more specific consideration |

Careful use of AV nodal blocking agents |

This table is not intended to summarize the guidelines but mainly as a guideline focusing on criteria of intervention.15 Surgical interval also depends on specific anatomical criteria and should always be clearly individualized. The recommendation in parenthesis are those of the American Heart Association guideline consensus with a class I recommendation being considered beneficial, a class IIa, considered probably beneficial and a class IIb recommendations where the risk benefit ratio is less well established. This table focusses on management of adults with CHD. Most of these recommendations are also valid for patients in childhood.

AV: atrioventricular

PG: pulmonary gradient

This point of non-recovery of the RV has been subject of debate for some time. In adult patients with severe PAH undergoing lung transplantation, the RV usually recovers completely. This suggests that the RV has a significant ability to reverse remodel. In patients with ASD, RV dilatation usually subsides with 2 to 24 months after repair [7]. Some studies have however shown that RV dilatation may persist in some patients for up to 5 years after the repair [56]. Atrial reverse remodeling also occurs after repair of the ASD but is less prominent in patients with late repair (> 40 years old). Normalization of diastolic and systolic RV myocardial velocities has been noted early after device closure (within 1 month) especially in younger patients. In patients with TOF, pulmonary valve replacement in case of dilated RV, often leads to a reduction in RV volumes by 35% to 40% [57]. In both adults and children, studies have shown that normalization of RV volumes is more limited in patients with RV end-diastolic volumes greater than 170 to 200 mL/m2. Whether complete normalization of RV volume is necessary for functional recovery has, however, not yet been determined. In patients with RVOT obstruction, the RV usually completely recovers. Table 2 summarizes some of the indications for surgical repair of selected CHD affecting the right heart.

The surgical technique may also influence the need for reoperation in patients with CHD. For example, Lindeberg et al. recently reported in a 50 years single center of TOF surgical experience that freedom from reoperation was less than 30% 15 years after transannular patch usage whereas it was near to 70% in patients without transannular patch [58].

Medical Therapy

The major advances made in the treatment of CHD and right heart failure have mainly been achieved with the introduction of pulmonary vasodilators in patients with severe pulmonary vascular disease. Neurohormonal blockade has not been shown to be beneficial in patients with RV failure although it is sometimes used in patients with systemic right ventricles. Most of studies are underpowered and clinical endpoint is not always clearly defined. Tables 3 to 5 summarize selected key trials and studies relative to medical therapy of patients with CHD [59-75].

Table 3.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers in RHF.

| Study | Study population | Characteristics | N | Design | Main findings * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dore et al. 2005 [59] | Systemic RV (TGA) |

Majority NYHA I RVEF 42% |

29 | Multicenter RCT crossover design Losartan vs. placebo for 15 weeks |

No difference in peak VO2, exercise duration or NT- proBNP levels. |

| Lester et al. 2001 [60] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) |

Age > 13 yrs NYHA < IV RVEF 48% |

7 | RCT, crossover design. Losartan vs. placebo for 8 weeks |

Beneficial effect: ↑exercise time by 18%, ↓ regurgitant volume by 63.5%, ↑ RVEF 6%‡ |

| Robinson et al. 2002 [61] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) |

NYHA I Age 7 to 21 yrs CI 2.2 L/min/m2 |

8 | Single arm prospective study Enalapril for 1 year |

No difference in exercise duration, peak VO2 or cardiac index |

| Therrien et al. 2008 [62] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) |

Mainly NYHA class I Age > 18 yrs RVEF 44% |

17 | Multicenter RCT Ramipril vs. placebo for 1 year |

No difference in RVEF, RV volume or peak VO2 |

| Hechter et al. 2001 [63] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) |

Age > 26 yrs RVEF 47% |

26 | Retrospective study ACE-I from 6 to 126 months |

No difference in peak VO2, exercise duration |

Unless otherwise specified, the results refer to statistically significant findings (p<0.05). The changes reported refer to relative changes in mean effect size or when indicated by ‡ changes in absolute effect size. Abbreviations as in previous tables. TGA indicates transposition of great arteries; TTPG, trans tricuspid pressure gradient

Table 5.

Trials on endothelin receptor antagonists and sildenafil in CHD affecting the right heart.

| Study | Study Population | n | Study Design | Drug | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galié et al. (BREATH-5), 2006 [69] |

Septal defects >12 years |

37 | Randomized Controlled Trial |

Bosentan | improved exercise capacity and pulmonary hemodynamics |

| Gatzoulis et al. 2005 [70] | Eisenmenger Adults |

10 | Prospective open trial |

Bosentan | improved exercise capacity, pulmonary hemodynamics and RV systolic function |

| Sitbon et al., 2006 [71] | ASD, VSD and Eisenmenger Adults |

27 | Retrospective analysis |

Bosentan | improved functionnal class, exercise capacity and pulmonary hemodynamic |

| Jing et al. , 2010 [72] | Heart septal defects Adults |

34 | Multi-open label trial | Bosentan | improved functionnal class, exercise capacity and pulmonary hemodynamic |

| Uhm et al. 2010 [73] | post-operative (AVSD repair, Fontan) Children |

75 | Retrospective analysis |

Oral Sildenafil | Well tolerated, no significant clinical improvement |

| Zeng et al., 2011 [74] | AVSD, PDA Adults |

55 | Prospective Multicenter trial |

Oral Sildenafil | improved exercise capacity and pulmonary hemodynamics without any side effects on systemic vasculature |

| Schulze-Neick et al., 2003 [75] |

AVSD, PDA, miscellaneous Children |

12 | Prospective trial | Intravenous Sildenafil |

more effective than inhaled NO to improve pulmonary hemodynamics; increased post-operative intrapulmonary shunting and had no significant clinical benefits |

CHD: Congenital Heart Disease; ASD: Atrial Septal Defect; VSD: Ventricular Septal Defect; PDA: Patent Ductus Arteriosus; NO: Nitric Oxyde

Neurohormonal blockade in left heart failure has been shown to improve functional class and survival in adult patients [76]. Both upregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and sympathetic activation in response to low cardiac output are harmful for the failing heart. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have positive effects on cardiac connective tissue remodeling in addition to beneficial hemodynamic effects [77]. Beta-blockers decrease myocyte apoptosis induced by catecholamine excess [78].

With regards to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAS) blockade, although early reports were encouraging, this has not been systematically demonstrated in all studies (Table 3) [59-63]. In a multicenter randomized double blind placebo-controlled crossover clinical trial, Dore et al. did not find any clinical benefit of Losartan in 29 adults with failed systemic RV. They hypothesized that minimal baseline activation of the RAS in this population may explain the lack of effect despite 15 weeks of treatment. Local production of angiotensin II has not been well quantified within the RV myocardium of CHD patients [59]. Moreover, Therrien et al. did not find any functional or geometrical improvement of systemic RV despite one-year Ramipril treatment after atrial switch for TGA [62].

Right ventricular chronotropic response is one of the main mechanisms to adapt to unusual loading conditions. Chronic atrioventricular conduct abnormalities are further commonly observed after surgical repair of CHD. Careful usage of beta-blockers is then required in patients with CHD. Clinical experience of beta-blockade employment in case of a failing right heart has been limited by the small sample size of studies (Table 4) [64-68].

Table 4.

Beta blockade in patients with congenital heart disease.

| Study | Etiology | Patient Characteristics |

N | Study Design | Main findings * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaddy et al. 2007 [64] |

Dilated CM and systemic RV |

Age < 13 yrs LVEF 27% NYHA class II & III |

161 | Multicenter RCT Carvedilol vs. Placebo for 8 months |

No difference. In patients with systemic LV, a trend towards improvement was noted however |

| Doughan et al. 2007 [65] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) | Adults RVEF 35% NYHA class I to III |

60 | Retrospective study. 4 months Carvedilol or Metoprolol for |

Beneficial effect: ↓NYHA class especially if pacemaker or initial NYHA class III Prevents further chamber dilatation |

| Josephson et al. 2006 [66] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) | Adults NYHA mainly class II RV diameter 41.5 mm |

8 | Retrospective study. Median FU of 3 yrs Carvedilol Metoprolol, Sotalol |

Beneficial effect: ↓ NYHA class in 5 patients |

| Giardini et al. 2007 [67] |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) L-TGA |

Age > 18 yrs NYHA class II & III RVEF= 34% |

8 | Single arm prospective Carvedilol for 12 months |

Beneficial effect: ↓ RVED volume by 6%, ↑RVEF 6% ‡. No change in peak VO2. |

| Norozi et al. 2007 [68] |

Tetralogy of Fallot | NYHA I and II Adults LVEF= 57% CI = 3.8 L/min/m2 |

33 | RCT Bisoprolol vs. placebo for 6 months |

No difference in peak VO2, RVEF, ventricular volumes, NYHA class |

Unless otherwise specified, the results refer to statistically significant findings (p<0.05). The changes reported refer to relative changes in mean effect size or when indicated by ‡ changes in absolute effect size. Abbreviations as in previous tables. RVED indicates RV end-diastolic volume

The theoretical possibility of worsening of right-to-left shunting raises questions about the safety of using pulmonary artery vasodilator therapies. Practically, these agents (intravenous prostacyclin and oral sildenafil) have yielded improvements in hemodynamics, exercise tolerance, and/or systemic arterial oxygen saturation in limited case studies (Table 5) [69-75]. Results of the first randomized, controlled trial of medical therapy in adults with Eisenmenger syndrome due to predominantly either ASD or VSD, with oral Bosentan compared with placebo (BREATHE-5, the Bosentan Randomized trial of Endothelin Antagonist THErapy-5), documented therapeutic safety and improvement in symptomatic measures, 6-minute walk distance, and hemodynamics after short-term (4 months) use of Bosentan [69]. The use of these agents should be restricted to centers with demonstrated expertise in CHD-PAH.

All of previous studies on medical therapy in patients with CHD and right HF are limited by the heterogeneity of the patient population, the small sample size and by the lack of long-time follow-up. Functional results from a randomized controlled trial using Valsartan are expected in failed systemic RV from congenitally and surgically corrected TGA patients [79]. There is little evidence that conventional therapies for heart failure can be applied today in adults with CHD. Patients should be referred to clinical research protocols.

Another very important aspect to emphasize in managing patients with CHD and right heart failure is that pregnancy can be contraindicated in patients with CHD and right heart disease and advice should always be sought from an expert in CHD. In general patients with severe right heart failure or severe pulmonary vascular disease should avoid pregnancy.

Resynchronization Therapy and Prevention of Sudden Death

Ventricular dyssynchrony related to CHD can occur in adulthood even following surgical correction of the underlying disease and ventricular dyssynchrony is commonly associated with higher rates of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. There is strong evidence that cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) can improve exercise capacity, functional status and survival in left ventricular failure [80,81]. Decreasing contractility and myocardial blood flow may result in part from disturbance between electrical and mechanical functions in longstanding CHD [82,83]. CRT application in this heterogeneous population has to be defined. Recent studies are summarized in table 6 [84-87].

Table 6.

Resynchronization therapy in patients with RHF.

| Study | Study population | Characteristics | N | Design | Main findings * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janousek et al. 2001 [84] |

Congenital Heart

disease |

Children with acute post-operative HF with conduction delay |

20 | Prospective study |

Beneficial effects. Improvement in hemodynamics (systolic blood pressure) |

| Dubin et al. 2003 [85] |

Congenital Heart

disease |

Chronic RV dysfunction RBBB TOF, aortic stenosis after Ross procedure |

7 | Prospective Multipacing sites, conductance catheter |

Beneficial effect. Atrioventricular augments RV and systemic performance (↑CI by 17±8%,↑ in RV dP/dt ) |

| Janousek et al. 2004 [86] |

Congenital Heart

Disease |

D-TGA (atrial baffle) L-TGA | 8 | Prospective |

Beneficial effect. ↑ RVEF by 9.6%, ↓ RVMPI by 7.7%. |

| Dubin et al. 2005 [87] |

Congenital Heart

Disease and Pediatric |

CHD and dilated CMP and congenital AV block |

103 | Multicenter Study (22 centers) |

Beneficial effects in all 3 groups. Average ↑ in EF 11.9% to 16.1%. Responders had lower baseline EF. |

Unless otherwise specified, the results refer to statistically significant findings (p<0.05). The changes reported refer to relative changes in mean effect size or when indicated by ‡ changes in absolute effect size. Abbreviations as in previous tables. EF indicates ejection fraction, RVMPI indicates RV myocardial performance index

Right bundle branch block is a significant predictor of ventricular arrhythmias in repaired TOF. Lumens et al. have demonstrated hemodynamic conditions and contractility improvement after RV free wall electrical stimulation in a model of PAH related heart failure [88]. Indications of CRT after TOF repair should probably be focused on the infundibulum rather than RV free wall motion because QRS duration may preferentially reflect RVOT abnormalities [89]. Precise definition of pacing sites should be an important factor for success. Between one third to an half of both congenitally corrected and repaired TGA have an increased QRS duration. Reduced myocardial contractility has been correlated with ventricular dyssynchrony in these patients [90,91]. Overall results are limited by the heterogeneity and small patients numbers. Further clinical randomized controlled studies are needed to assess long-term functional benefit of CRT in CHD adults [92].

Predicting sudden death in patients with RV disease remains difficult. Studies have mainly addressed the risk of sudden death in TOF and ARVC [93]. In patients with TOF, prolonged QRS duration (QRS > 180 ms) is a sensitive, although less specific predictor of sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) and sudden death. For symptomatic TOF patients with inducible VT, correction of physiologic abnormalities and timely surgery may further decrease the incidence of VT or sudden death [94]. Implantable defibrillators are considered in patients with ARVC and high risk markers of VT.

Transplantation

In the absence of severe pulmonary vascular disease, patients with CHD and refractory RHF should be considered for heart transplantation. CHD represents approximately 2.5% of cases undergoing heart transplantation per year [95]. There will also be an increasing number of pediatric patients who underwent heart transplantation as children that will represent for retransplantation as adults [96]. In terms of risk, congenital etiology of pre-transplant heart disease results in increased risk of 1 year mortality (relative risk of 2.27) [95]. In patients surviving the first year, the long term risk was better for CHD than non-ischemic but this could represent highly selected patients in the previous era.

Patients with Eisenmenger physiology and refractory RHF should be considered for heart and lung transplantation. Survival rates after 5, 10, 15 and 20 years are 66%, 49%, 35%, and 28% respectively. Survival was similar in heart and lung recipients with or without previous Eisenmenger syndrome [97].

Regenerative Therapy in Congenital Heart Disease Affecting the Right Heart

Stem cell therapy has been mainly studied both experimentally and clinically in the setting of ischemic heart disease and dilated cardiomyopathy. In contrast, there have been a limited number of studies focusing on congenital heart disease affecting the right heart. One of the main reasons may be that the mainstay of therapy is corrective surgery and that stem cell therapy is still at early stages of development. In a recent study by Yerebakan et al., autologous umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation preserves right ventricular function, especially diastolic properties, in a model of chronic RV volume overload [98].

Although many clinical trials have studied cell therapy for left ventricle failure, no attempt was made to treat failed RV by stem cells delivery. Since 2000, a better understanding of cardiac stem cell therapy has led to improvement of cell delivery and choice of cell type. Two major mechanisms of action have to be considered in stem cell therapy: cardiomyocytes substitution and paracrine effects. By now, paracrine effects are the most convincible mechanism of action of stem cell therapy. Activation of paracrine factors may lead to increased angiogenesis, decreased apoptosis, improved ventricular remodeling, and activation of endogenous cardiac progenitor cells [99-101]. These paracrine effects raise a real interest among physicians dealing with CHD because all of them could improve RV function in CHD. Cardiac stem cells, human embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells are the new cell types that are currently studied. At present there is still no consensus on which cell-type is the best for cardiac therapy. In addition, cell delivery techniques need to be improved concurrently. Direct injection or intra-vascular administration may induce stem cells clusters which could promote arrhythmia. Biocompatible scaffold seeded with cells that could be applied to the heart seems to be for the moment the best solution. In conclusion, stem cell therapy is an active research topic that will also involve active investigation in RV failure.

Conclusion

Over the last five decades there have been great advances in the management of CHD affecting the right heart. Among them, we find the development of breakthrough surgeries such as the arterial switch operation for d-TGA, the development of criteria for optimal timing of corrective surgery and the introduction of pulmonary vasodilator therapy for symptomatic relief of patients with Eisenmenger physiology as seminal findings. Future advances in the field will focus on the development of targeted therapy for late or post-operative RV failure. Advances in bioengineering may also lead to development of novel conduits and new biomaterials that can help regenerate the failing RV.

Submit your next manuscript and get advantages of OMICS Group submissions.

Unique features

User friendly/feasible website-translation of your paper to 50 world’s leading languages

Audio Version of published paper

Digital articles to share and explore

Special features

200 Open Access Journals

15,000 editorial team

21 days rapid review process

Quality and quick editorial, review and publication processing

Indexing at PubMed (partial), Scopus, DOAJ, EBSCO, Index Copernicus and Google Scholar etc

Sharing Option: Social Networking Enabled

Authors, Reviewers and Editors rewarded with online Scientific Credits

Better discount for your subsequent articles

Submit your manuscript at: www.editorialmanager.com/clinicalgroup

Acknowledgments

Support This work is support by funds of the National Institute of Health R01 HL095571 (Joseph C. Wu).

Abbreviations

- CHD

Congenital Heart Disease

- RV

Right Ventricle

- TGA

Transposition of Great Arteries

- ASD

Atrial Septal Defect

- VSD

Ventricular Septal Defect

- TOF

Tetralogy of Fallot

- PS

Pulmonary Stenosis

- ARVC

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

- RHF

Right Heart Failure

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- TR

Tricuspid Regurgitation

- RVOT

Right Ventricular Outflow Tract

- RVPO

Right Ventricular Pressure Overload

- DCRV

Double Chambered Right Ventricle

- cc-TGA

Congenitally Corrected Transposition of Great Arteries

- d-TGA

Dextro-Transposition of Great Arteries

- PAH

Pulmonary Artery Hypertension

- LV

Left Ventricle

- VT

Ventricular Tachycardia

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierpont ME, Basson CT, Benson DW, Jr, Gelb BD, Giglia TM, et al. Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:3015–3038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, de Haan F, Deanfield JE, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010) Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2915–2957. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad F, Doyle R, Murphy DJ, Hunt SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2008;117:1717–1731. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad F, Hunt SA, Rosenthal DN, Murphy DJ. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part I: Anatomy, physiology, aging, and functional assessment of the right ventricle. Circulation. 2008;117:1436–1448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolger AP, Sharma R, Li W, Leenarts M, Kalra PR, et al. Neurohormonal activation and the chronic heart failure syndrome in adults with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2002;106:92–99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020009.30736.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation. 2006;114:1645–1653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davlouros PA, Niwa K, Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. The right ventricle in congenital heart disease. Heart. 2006;92:i27–38. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertranou EG, Blackstone EH, Hazelrig JB, Turner ME, Kirklin JW. Life expectancy without surgery in tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:458–466. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Felice V, Zummo G. Tetralogy of fallot as a model to study cardiac progenitor cell migration and differentiation during heart development. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009;19:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lillehei CW, Varco RL, Cohen M, Warden HE, Gott VL, et al. The first open heart corrections of tetralogy of Fallot. A 26-31 year follow-up of 106 patients. Ann Surg. 1986;204:490–502. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198610000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liebman J, Cullum L, Belloc NB. Natural history of transpositon of the great arteries. Anatomy and birth and death characteristics. Circulation. 1969;40:237–262. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso-Gonzalez R, Dimopoulos K, Ho S, Oliver JM, Gatzoulis MA. The right heart and pulmonary circulation (IX). The right heart in adults with congenital heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:1070–1086. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ly M, Belli E, Leobon B, Kortas C, Grollmuss OE, et al. Results of the double switch operation for congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubiszewska B, Gosiewska E, Hoffman P, Teresinska A, Rozanski J, et al. Myocardial perfusion and function of the systemic right ventricle in patients after atrial switch procedure for complete transposition: long-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodge-Khatami A, Kadner A, Berger Md F, Dave H, Turina MI, et al. In the footsteps of senning: lessons learned from atrial repair of transposition of the great arteries. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moons P, Gewillig M, Sluysmans T, Verhaaren H, Viart P, et al. Long term outcome up to 30 years after the Mustard or Senning operation: a nationwide multicentre study in Belgium. Heart. 2004;90:307–313. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2002.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azaouagh A, Churzidse S, Konorza T, Erbel R. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: a review and update. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh N, Haddad H. Recent progress in the genetics of cardiomyopathy and its role in the clinical evaluation of patients with cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:155–164. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283439797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Migliore F, Zorzi A, Silvano M, Rigato I, Basso C, et al. Clinical management of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: an update. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2918–2928. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, Thierfelder L. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Heart fail clin. 2010;6:161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe BS, Therrien J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Pilote L, Martucci G, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension in the congenital heart disease adult population impact on outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelfriet PM, Duffels MG, Moller T, Boersma E, Tijssen JG, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults born with a heart septal defect: the Euro Heart Survey on adult congenital heart disease. Heart. 2007;93:682–687. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.098848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trojnarska O, Plaskota K. Therapeutic methods used in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Cardiol J. 2009;16:500–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hopkins WE, Waggoner AD. Severe pulmonary hypertension without right ventricular failure: the unique hearts of patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:34–38. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, Broberg CS, Kaya MG, Naghotra US, et al. Presentation, survival prospects, and predictors of death in Eisenmenger syndrome: a combined retrospective and case-control study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1737–1742. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopkins WE, Ochoa LL, Richardson GW, Trulock EP. Comparison of the hemodynamics and survival of adults with severe primary pulmonary hypertension or Eisenmenger syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hornung TS, Bernard EJ, Jaeggi ET, Howman-Giles RB, Celermajer DS, et al. Myocardial perfusion defects and associated systemic ventricular dysfunction in congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Heart. 1998;80:322–326. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millane T, Bernard EJ, Jaeggi E, Howman-Giles RB, Uren RF, et al. Role of ischemia and infarction in late right ventricular dysfunction after atrial repair of transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1661–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hauser M, Bengel FM, Hager A, Kuehn A, Nekolla SG, et al. Impaired myocardial blood flow and coronary flow reserve of the anatomical right systemic ventricle in patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries. Heart. 2003;89:1231–1235. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.10.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Henderson SC, Long CS, Kraskauskas D, et al. Chronic pulmonary artery pressure elevation is insufficient to explain right heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:1951–1960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.883843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monreal G, Youtz DJ, Phillips AB, Eyman ME, Gorr MW, et al. Right ventricular remodeling in restrictive ventricular septal defect. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuehne T, Yilmaz S, Steendijk P, Moore P, Groenink M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of right ventricular pressure-volume loops: in vivo validation and clinical application in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:2010–2016. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143138.02493.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redington AN, Rigby ML, Hayes A, Penny D. Right ventricular diastolic function in children. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:329–330. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norgard G, Gatzoulis MA, Josen M, Cullen S, Redington AN. Does restrictive right ventricular physiology in the early postoperative period predict subsequent right ventricular restriction after repair of tetralogy of Fallot? Heart. 1998;79:481–484. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.5.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cullen S, Shore D, Redington A. Characterization of right ventricular diastolic performance after complete repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Restrictive physiology predicts slow postoperative recovery. Circulation. 1995;91:1782–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatzoulis MA, Clark AL, Cullen S, Newman CG, Redington AN. Right ventricular diastolic function 15 to 35 years after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Restrictive physiology predicts superior exercise performance. Circulation. 1995;91:1775–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda S, Hamada M, Hiwada K. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis with enhanced expression of P53 and Bax in right ventricle after pulmonary arterial banding. Life Sci. 1999;65:925–933. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minegishi S, Kitahori K, Murakami A, Ono M. Mechanism of pressure-overload right ventricular hypertrophy in infant rabbits. Int Heart J. 2011;52:56–60. doi: 10.1536/ihj.52.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakao K, Minobe W, Roden R, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Myosin heavy chain gene expression in human heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2362–2370. doi: 10.1172/JCI119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowes BD, Minobe W, Abraham WT, Rizeq MN, Bohlmeyer TJ, et al. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart. Downregulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2315–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI119770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benoist D, Stones R, Drinkhill M, Bernus O, White E. Arrhythmogenic substrate in hearts of rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2230–2237. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01226.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marino TA, Kent RL, Uboh CE, Fernandez E, Thompson EW, et al. Structural analysis of pressure versus volume overload hypertrophy of cat right ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:H371–379. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.2.H371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambert V, Capderou A, Le Bret E, Rucker-Martin C, Deroubaix E, et al. Right ventricular failure secondary to chronic overload in congenital heart disease: an experimental model for therapeutic innovation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1197–1204. 1204.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Modesti PA, Vanni S, Bertolozzi I, Cecioni I, Lumachi C, et al. Different growth factor activation in the right and left ventricles in experimental volume overload. Hypertension. 2004;43:101–108. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000104720.76179.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Courboulin A, Paulin R, Giguere NJ, Saksouk N, Perreault T, et al. Role for miR-204 in human pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Exp Med. 2011;208:535–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda S, He A, Kong SW, Lu J, Bejar R, et al. MicroRNA-1 negatively regulates expression of the hypertrophy-associated calmodulin and Mef2a genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2193–2204. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01222-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feldt RH, Driscoll DJ, Offord KP, Cha RH, Perrault J, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy after the Fontan operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:672–680. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheung MM, Smallhorn JF, Redington AN, Vogel M. The effects of changes in loading conditions and modulation of inotropic state on the myocardial performance index: comparison with conductance catheter measurements. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2238–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel M, Sponring J, Cullen S, Deanfield JE, Redington AN. Regional wall motion and abnormalities of electrical depolarization and repolarization in patients after surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Circulation. 2001;103:1669–1673. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.12.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogel M, Schmidt MR, Kristiansen SB, Cheung M, White PA, et al. Validation of myocardial acceleration during isovolumic contraction as a novel noninvasive index of right ventricular contractility: comparison with ventricular pressure-volume relations in an animal model. Circulation. 2002;105:1693–1699. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013773.67850.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vogel M, Derrick G, White PA, Cullen S, Aichner H, et al. Systemic ventricular function in patients with transposition of the great arteries after atrial repair: a tissue Doppler and conductance catheter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oikawa M, Kagaya Y, Otani H, Sakuma M, Demachi J, et al. Increased [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation in right ventricular free wall in patients with pulmonary hypertension and the effect of epoprostenol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1849–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Graham TP., Jr Ventricular performance in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1991;84:2259–2274. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.6.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salehian O, Horlick E, Schwerzmann M, Haberer K, McLaughlin P, et al. Improvements in cardiac form and function after transcatheter closure of secundum atrial septal defects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindberg HL, Saatvedt K, Seem E, Hoel T, Birkeland S. Single-center 50 years’ experience with surgical management of tetralogy of Fallot. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dore A, Houde C, Chan KL, Ducharme A, Khairy P, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockade and exercise capacity in adults with systemic right ventricles: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Circulation. 2005;112:2411–2416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lester SJ, McElhinney DB, Viloria E, Reddy GP, Ryan E, et al. Effects of losartan in patients with a systemically functioning morphologic right ventricle after atrial repair of transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1314–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson B, Heise CT, Moore JW, Anella J, Sokoloski M, et al. Afterload reduction therapy in patients following intraatrial baffle operation for transposition of the great arteries. Pediatr Cardiol. 2002;23:618–623. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Therrien J, Provost Y, Harrison J, Connelly M, Kaemmerer H, et al. Effect of angiotensin receptor blockade on systemic right ventricular function and size: a small, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hechter SJ, Fredriksen PM, Liu P, Veldtman G, Merchant N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in adults after the Mustard procedure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:660–663. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaddy RE, Boucek MM, Hsu DT, Boucek RJ, Canter CE, et al. Carvedilol for children and adolescents with heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1171–1179. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doughan AR, McConnell ME, Book WM. Effect of beta blockers (carvedilol or metoprolol XL) in patients with transposition of great arteries and dysfunction of the systemic right ventricle. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:704–706. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Josephson CB, Howlett JG, Jackson SD, Finley J, Kells CM. A case series of systemic right ventricular dysfunction post atrial switch for simple D-transposition of the great arteries: the impact of beta-blockade. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giardini A, Lovato L, Donti A, Formigari R, Gargiulo G, et al. A pilot study on the effects of carvedilol on right ventricular remodelling and exercise tolerance in patients with systemic right ventricle. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Norozi K, Bahlmann J, Raab B, Alpers V, Arnhold JO, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of beta-blockade in patients who have undergone surgical correction of tetralogy of Fallot. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:372–379. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Galie N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, et al. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gatzoulis MA, Rogers P, Li W, Harries C, Cramer D, et al. Safety and tolerability of bosentan in adults with Eisenmenger physiology. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sitbon O, Beghetti M, Petit J, Iserin L, Humbert M, et al. Bosentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart defects. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jing ZC, Strange G, Zhu XY, Zhou DX, Shen JY, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of bosentan in Chinese patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uhm JY, Jhang WK, Park JJ, Seo DM, Yun SC, et al. Postoperative use of oral sildenafil in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:515–520. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeng WJ, Sun YJ, Gu Q, Xiong CM, Li JJ, et al. Impact of Sildenafil on Survival of Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0091270011418656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schulze-Neick I, Hartenstein P, Li J, Stiller B, Nagdyman N, et al. Intravenous sildenafil is a potent pulmonary vasodilator in children with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2003;108:II167–173. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087384.76615.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pfeffer MA, Lamas GA, Vaughan DE, Parisi AF, Braunwald E. Effect of captopril on progressive ventricular dilatation after anterior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:80–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807143190204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Communal C, Singh K, Pimentel DR, Colucci WS. Norepinephrine stimulates apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes by activation of the beta-adrenergic pathway. Circulation. 1998;98:1329–1. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van der Bom T, Winter MM, Bouma BJ, Groenink M, Vliegen HW, et al. Rationale and design of a trial on the effect of angiotensin II receptor blockers on the function of the systemic right ventricle. Am Heart J. 2010;160:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Young JB, Abraham WT, Smith AL, Leon AR, Lieberman R, et al. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2685–2694. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gatzoulis MA, Till JA, Somerville J, Redington AN. Mechanoelectrical interaction in tetralogy of Fallot. QRS prolongation relates to right ventricular size and predicts malignant ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Circulation. 1995;92:231–237. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scherptong RW, Hazekamp MG, Mulder BJ, Wijers O, Swenne CA, et al. Follow-up after pulmonary valve replacement in adults with tetralogy of Fallot: association between QRS duration and outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Janousek J, Vojtovic P, Hucin B, Tlaskal T, Gebauer RA, et al. Resynchronization pacing is a useful adjunct to the management of acute heart failure after surgery for congenital heart defects. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dubin AM, Feinstein JA, Reddy VM, Hanley FL, Van Hare GF, et al. Electrical resynchronization: a novel therapy for the failing right ventricle. Circulation. 2003;107:2287–2289. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070930.33499.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Janousek J, Tomek V, Chaloupecky VA, Reich O, Gebauer RA, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: a novel adjunct to the treatment and prevention of systemic right ventricular failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1927–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dubin AM, Janousek J, Rhee E, Strieper MJ, Cecchin F, et al. Resynchronization therapy in pediatric and congenital heart disease patients: an international multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2277–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lumens J, Arts T, Broers B, Boomars KA, van Paassen P, et al. Right ventricular free wall pacing improves cardiac pump function in severe pulmonary arterial hypertension: a computer simulation analysis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H2196–2205. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00870.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uebing A, Gibson DG, Babu-Narayan SV, Diller GP, Dimopoulos K, et al. Right ventricular mechanics and QRS duration in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot: implications of infundibular disease. Circulation. 2007;116:1532–1539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cecchin F, Frangini PA, Brown DW, Fynn-Thompson F, Alexander ME, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (and multisite pacing) in pediatrics and congenital heart disease: five years experience in a single institution. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chow PC, Liang XC, Lam WW, Cheung EW, Wong KT, et al. Mechanical right ventricular dyssynchrony in patients after atrial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thambo JB, Dos Santos P, Bordachar P. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with congenital heart disease. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease) Circulation. 2008;118:e714–833. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Michaud J, Horduna I, Dubuc M, Khairy P. ICD-unresponsive ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1827–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Aurora P, Christie JD, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult heart transplant report--2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hunt SA, Haddad F. The changing face of heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fadel E, Mercier O, Mussot S, Leroy-Ladurie F, Cerrina J, et al. Long-term outcome of double-lung and heart-lung transplantation for pulmonary hypertension: a comparative retrospective study of 219 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yerebakan C, Sandica E, Prietz S, Klopsch C, Ugurlucan M, et al. Autologous umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation preserves right ventricular function in a novel model of chronic right ventricular volume overload. Cell transplant. 2009;18:855–868. doi: 10.3727/096368909X471170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Perez-Ilzarbe M, Agbulut O, Pelacho B, Ciorba C, San Jose-Eneriz E, et al. Characterization of the paracrine effects of human skeletal myoblasts transplanted in infarcted myocardium. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Lee CW, Barr S, et al. Marrow-derived stromal cells express genes encoding a broad spectrum of arteriogenic cytokines and promote in vitro and in vivo arteriogenesis through paracrine mechanisms. Circ Res. 2004;94:678–685. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000118601.37875.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vieira JM, Riley PR. Epicardium-derived cells: a new source of regenerative capacity. Heart. 2011;97:15–19. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.193292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]