Abstract

Purpose

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatment self-efficacy is the confidence held by an individual in her or his ability to follow treatment recommendations, including specific HIV care such as initiating and adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART). The purpose of this study was to explore the potential mediating role of treatment adherence self-efficacy in the relationships between Social Cognitive Theory constructs and self- reported ART adherence.

Design

Cross-sectional and descriptive. The study was conducted between 2009 and 2011 and included 1,414 participants who lived in the United States or Puerto Rico and were taking antiretroviral medications.

Methods

Social cognitive constructs were tested specifically: behaviors (three adherence measures each consisting of one item about adherence at 3-day and 30-day along with the adherence rating scale), cognitive or personal factors (the Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale to assess for depressive symptoms, the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) to assess physical functioning, one item about physical condition, one item about comorbidity), environmental influences (the Social Capital Scale, one item about social support), and treatment self-efficacy (HIV Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale). Analysis included descriptive statistics and regression.

Results

The average participant was 47 years old, male, and a racial or ethnic minority, had an education of high school or less, had barely adequate or totally inadequate income, did not work, had health insurance, and was living with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome for 15 years. The model provided support for adherence self-efficacy as a robust predictor of ART adherence behavior, serving a partial mediating role between environmental influences and cognitive or personal factors.

Conclusions

Although other factors such as depressive symptoms and lack of social capital impact adherence to ART, nurses can focus on increasing treatment self-efficacy through diverse interactional strategies using principles of adult learning and strategies to improve health literacy.

Clinical Relevance

Adherence to ART reduces the viral load thereby decreasing morbidity and mortality and risk of transmission to uninfected persons. Nurses need to use a variety of strategies to increase treatment self-efficacy.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, social cognitive theory, self-efficacy, adherence

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has evolved into a chronic condition in regions of the world where healthcare systems provide treatment. HIV-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is now a chronic disease similar to other chronic illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension that require daily medications in order to control the associated pathology and optimize health (Volberding & Deeks, 2010). Regular adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) can reduce morbidity, mortality, and the likelihood of transmission of HIV to uninfected persons (Panel on Retroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2012). Irregular adherence, however, can result in viral mutations, which render classes of antiretroviral medications inefficient and, if the virus is transmitted to another person, increases the spread of resistant strains of HIV type 1. Recent developments have offered the possibility of once daily dosing, and pharmaceutical combinations include more than one active medication in one pill. This has significantly reduced adherence barriers related to complex regimen and dosing patterns. However, ART adherence remains challenging for many persons, and thus the benefits of ART are not fully realized (Phillips, 2011; Protopopescu et al., 2009). Approaches to optimizing medication adherence may be improved by placing medication adherence within the larger framework of chronic disease self-management.

Social Cognitive Theory suggests that perceived self-efficacy is a significant determinant of behavior that operates partially independently of underlying skills (Bandura, 1986). Effective chronic disease self-management requires considerable skills and is associated with improved outcomes, reduced mortality and disability, improved quality of life, and reduced healthcare costs (Richard & Shea, 2011). HIV treatment self-efficacy is defined as the confidence held by an individual in her or his ability to follow treatment recommendations and includes any actions that the person living with HIV does to promote health, including specific HIV care such as initiating and adhering to ART; attending health-related appointments; and more general health-promoting practices related to nutrition, exercise, and sleep, along with avoiding use or abuse of cigarettes, alcohol, and medications (Johnson et al., 2007). The purpose of this article was to explore the potential mediating role of treatment adherence self-efficacy in the relationship between Social Cognitive Theory constructs and ART adherence in a large sample of persons living with HIV or AIDS (PLWHA) in the United States and Puerto Rico taking ART to treat their HIV disease.

Self-efficacy has been described as an antecedent skill for optimum treatment adherence (Shay, 2008). If it can be demonstrated that self-efficacy is a mediator or antecedent to treatment adherence, then nursing interventions can focus on increasing self-efficacy rather than treatment of lifelong comorbid conditions such as depression or improving limited financial resources. By improving treatment self-efficacy and, therefore, adherence to ART, PLWHA will receive greater benefit from existing treatments and decrease the transmission of the virus to uninfected others.

Background

Adherence describes the complement of actions taken to comply with intervention recommendations and is different from other behavior change outcomes (McBride et al., 2012). Growing recognition by healthcare providers that consumers are not following recommendations has led to a proliferation of strategies to improve treatment adherence. Observations indicate that treatment adherence has been declining steadily, but perhaps consumers are becoming more open with their health-care providers about adherence behaviors. This transition in dialog about whether clients are adhering to recommendations as part of their decision making may symbolize a shift toward a shared patient-provider decision-making framework. Current methods of improving adherence for chronic health problems are complex, with limited effectiveness. Haynes, Ackloo, Sahota, McDonald, and Yao (2008) argue that high priority should be given to fundamental and applied research concerning innovations to assist patients to follow recommended treatment options for chronic medical disorders.

Persons with higher initial levels of depression participating in chronic disease self-management programs had the greatest improvements in health distress compared to controls (Ritter, Lee, & Lorig, 2011). Factors related to treatment adherence for persons living with chronic illnesses include depression, social support, and self-efficacy (Shay, 2008). A meta-analysis of 12 studies of chronically ill patients, which did not include PLWHA, showed that depressed patients were three times more likely to be nonadherent with their medical treatment as nondepressed persons (DiMatteo, Lepper, Croghan, 2000). A meta-analysis found that depression and HIV treatment nonadherence has been consistent across samples over time and was not limited to clinical signs of depression (Gonzalez, Batchelder, Psaros, & Safren, 2011). Strong social support, especially practical support, was also related to better treatment adherence (DiMatteo, 2004) in chronically ill persons. In the United States and Puerto Rico, HIV infection has disproportionately impacted sexual minorities and injection drug user groups, both of whom have high rates of depression and limited social support. Men who have sex with men show higher rates of depression than other groups (Alvy et al., 2011), and injecting drug users often report limited social support and economic resources (Magnus et al., 2009).

Theoretical Framework

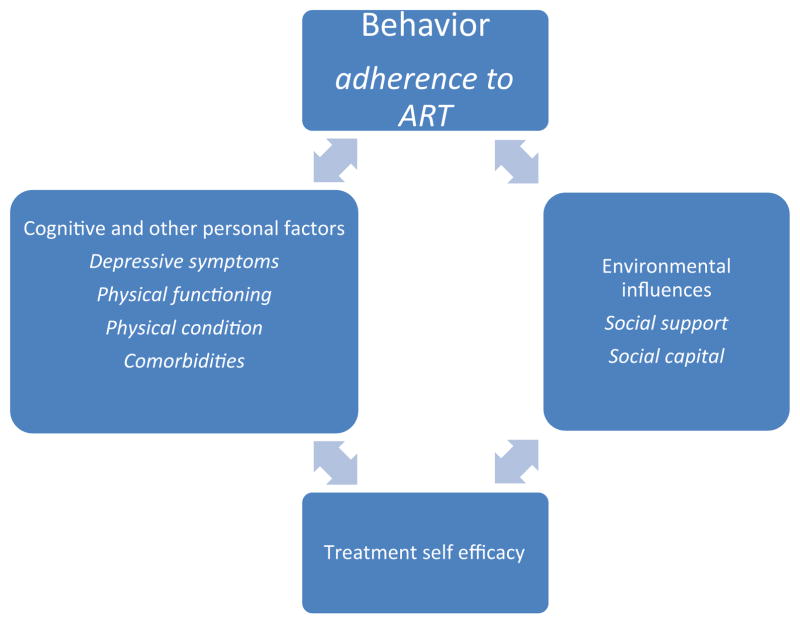

Social cognitive theory posits a model of triadic reciprocality where behavior, cognitive and other personal factors, and environmental influences operate interactively as determinants of each other (Bandura, 1986). Figure 1 presents the social cognitive triadic model with the three constructs and specific variables being tested and treatment self-efficacy as an antecedent mediator of the desired behavior: adherence to ART. Self-efficacy appraisals reflect the level of difficulty that individuals believe they can surmount to perform a specific behavior (Bandura, 2006); such as taking prescribed medications as directed by a healthcare provider.

Figure 1.

Social cognitive triadic model.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Methods

Sample and Setting

Data for this cross-sectional secondary analysis come from the International Nursing Network for HIV/AIDS Research Study V: Exploring the Role of Self-compassion, Self-efficacy and Self-esteem for HIV-positive Individuals Managing Their Disease. In the primary study, there were 16 sites from five countries and Puerto Rico; data collection started in August 2009 and ended in July 2011, and each site recruited approximately 100 to 300 participants (N = 2,182). Inclusion criteria were: adults (>18 years of age), living with HIV/AIDS, and receiving services from infectious disease clinics or AIDS service organizations. Prior to recruitment at study sites, the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, San Francisco, reviewed and approved the overall protocol, and each site also received approval from their local human subjects review committees.

This research study included 1,414 participants from the primary study who lived in the United States (California, Massachusetts, Washington, Illinois, New York, Ohio, North Carolina, Texas, Hawaii, and New Jersey) or Puerto Rico and who reported currently taking antiretroviral medications. The average participant was 47 years old, male, and a racial or ethnic minority, had an education of high school or less, had barely adequate or totally inadequate income, did not work, had health insurance, and was living with HIV/AIDS for 15 years (see Table 1 for additional information).

Table 1.

Demographic and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Information for Persons Taking HIV Antiretroviral Therapy (N = 1,414)a

| Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr); range: 18–74 yr | 46.6 (8.9) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1,019 (71.1) | |

| Female | 372 (26.3) | |

| Transgender | 28 (2) | |

| Race Asian/Pacific Islander | 61 (4.3) | |

| African American/Black | 567 (39.5) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 348 (24.3) | |

| Native American | 28 (20) | |

| White/Angelo | 374 (26.1) | |

| Education level | ||

| 11th grade or less | 350 (24.4) | |

| High school or GED | 569 (39.7) | |

| 2 yr college/AA | 312 (21.8) | |

| 4 yr college/BS/BA | 148 (10.3) | |

| Master’s degree or doctorate | 45 (3.1) | |

| Self-reported income adequacy | ||

| Totally inadequate | 334 (23.3) | |

| Barely adequate | 777 (54.2) | |

| Enough | 302 (21.1) | |

| Do not work for pay | 1140 (79.5) | |

| Has health insurance | 1,128 (78.7) | |

| Self-reported HIV indicators | ||

| Average year diagnosed with HIV/AIDS (range 1980–2011) | 1996 | |

| Diagnosed with AIDS | 653 (45.5) | |

| Don’t know viral load | 323 (22.8) | |

| Don’t know CD4 T cell count cubic millimeter of blood. A normal CD4 count in a healthy, HIV-negative adult can very but is usually between 600 and 1,200 CD4 Cells per mm3 | 418 (29.6) | |

Percentages might not add up to 100% due to some missing data.

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma; AA = associate of arts degree; BS = bachelor of science degree; BA = bachelor of arts degree.

Data Collection Procedures

Each site adhered to the common protocol, and all participants gave written informed consent before completing a pen-and-paper, cross-sectional survey. After completing the survey, all data were entered into an electronic database using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) programs and were de-identified. The de-identified data were sent to the coordinating center, cleaned, entered into the master database, and stored until all sites completed data collection and entry. Instruments were scored based on the instructions provided by the author. Original data were stored at each individual site.

Instruments

Treatment self-efficacy was measured by the HIV Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) which assesses a person’s confidence to carry out health-related behaviors (sticking to a treatment plan, including keeping appointments, adhering to medication) over the past month. This measure, which includes two subscales (Perseverance and Integration), has been associated with adherence to ART (Johnson et al., 2007; Webel et al., 2012). Subjects were asked, “How confident are you that you can. ..” on 12 items, with ratings from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident).

Cognitive and Other Personal Factors

Depressive symptoms were measured by the 20-item Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is a widely used nondiagnostic screening tool that measures the current level of depressive symptoms in community populations (Radloff, 1977). Items are rated 0 = never or rarely to 3 = mostly or all of the time. A total score can range from 0 to 60.

Physical functioning was measured using the Medical Outcome Study–Short Form, which is a multipurpose generic measurement of health status that contains 12 items that measure eight aspects of general health to include physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health issues, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health (Jones et al., 2001; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1995). The instrument uses a Likert scale of 1 to 3 for physical function items; 1 to 5 for bodily pain, social function, and general health perception items; 1 to 6 for vitality and mental health; and a dichotomous scale (yes or no) for the presence of role function items (Resnick & Nahm, 2001); higher scores indicate a better level of functioning.

Physical condition was measured with a single-item question asking participants about their perceived physical condition at the present time on a 10-point scale (1 = very poor, 10 = excellent). Comorbidity was measured by asking participants if they had other health conditions, such as tuberculosis, malaria, high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, or hepatitis, using a yes or no option and, if answered “yes,” to list the comorbidity.

Environmental Influences

Social capital was measured on the Social Capital instrument, which has eight subscales, including participation in the local community, social agency, feelings of trust and safety, neighborhood connections, friends and family connections, tolerance of diversity, value of life, and workplace connections; these items were summed to create a total social capital score. In our analysis, the three workplace connections items were dropped, as were two work-related questions that are part of the social agency dimension, due to low anticipated employment status, since the average unemployment rate in persons living with HIV/AIDS ranges from 62% to 74% (Cunningham et al., 2006), with the approval and recommendation of the scale’s authors. Participants were asked to rate each of the items on a 1–4 Likert-type scale, with higher scores being consistent with more social capital (Onyx & Bullen, 2000; Webel et al., 2012). Social support was measured with one question asking participants about their current perceived social support on a 10-point scale (1 = very poor, 10 = excellent).

Behavior

The behavior of interest was taking ART and was measured with three items. These items included 3-day visual analog, 30-day visual analog, and 30-day adherence rating scales.

The 3-day Visual Analog Scale for Medication Adherence is a one-item visual analog scale that is based on Walsh and colleague’s 30-day adherence assessment (Walsh, Mandalia, & Gazzard, 2002). Participants were asked to mark what percentage of the time they were able to take medications exactly as prescribed in the past 3 days, on a scale of 0% of the time to 100% of the time.

The 30-day Visual Analog Scale for Medication Adherence is a one-item visual analog scale adapted from Walsh and colleagues (Thames et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2002). Participants were asked to mark what percentage of the time they were able to take medications exactly as prescribed by their doctor in the past 30 days, on a scale of 0% of the time to 100% of the time.

The 30-day Adherence Rating is a one-item self-rating of ability to take all medications as prescribed using a 6-point scale from “very poor” to “excellent.” In a study of 643 visits by 156 study participants, Lu and colleagues (2008) compared both time frame and question format to data from Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) caps. Results showed that 1-month recall correlated more closely with MEMS caps than did 3- or 7-day recall. The study also found the 6-point scale to be more accurate than either frequency or percent responses.

Additional data were collected about demographic and illness-related characteristics, including age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, adequacy of income, health insurance, date first learned of HIV diagnosis, current CD4 T cell count, viral load, HIV transmission route, and general health. Table 1 present sample characteristics, and Table 2 presents the range, means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s α computed for this sample on each of the instruments used to measure the variables of interest.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the Instruments

| Name | Mean (SD) | Range | Cronbach’s α coefficients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment adherence self-efficacy | 95.99 (23.67) | 12–120 | 0.94 |

| Cognitive and other personal factors | |||

| Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale | 20.95 (11.62) | 0–57 | 0.86 |

| Physical functioning – SF 12 | 43.08 (10.3) | 10–67 | 0.81 (items 2a & 2b) |

| Physical condition | 6.85 (2.11) | 1–10 | Single item |

| Comorbidity | 0.68 (0.46) | 0–1 | Single item |

| Environmental influences | |||

| Social Capital Scale | 79.11 (16.92) | 2–120 | 0.88 |

| Social Support Scale | 7.20 (2.61) | 1–10 | Single item |

| Behavior: Adherence with HIV treatment | |||

| 3-day Visual Analog Scale for Medication Adherence | 90.05 (19.34) | 0–100 | Single item |

| 30-day Visual Analog Scale for Medication Adherence | 87.57 (19.35) | 0–100 | Single item |

| 30-day adherence rating | 3.99 (1.20) | 0–5 | Single item |

Results

Treatment self-efficacy was operationalized by the concepts identified on the HIV-ASES. Johnson et al. (2007) reported two factors on the HIV-ASES (Integration and Perseverance), but a principal components factor analysis with this sample found one factor with an eigenvalue of 7.807, which explained 65% of the variance; therefore, further analyses were computed using a total score.

Adherence to ART was operationalized by a factor score created by saving the factor yielded by the three adherence items: percentage correctly taken in the past 3 days, percentage taken correctly in the past 30 days, and self-rated adherence for the past 30 days. The eigenvalue for this factor was 2.3, which explained 78% of item variance, and item factor loadings were .92, .88, and .85.

Cognitive and other personal factors were operationalized by depressive symptoms measured by the CES-D, and physical health, which was operationalized by the factor yielded by three scores: the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) physical functioning scale, self-rated physical condition, and comorbid conditions. The eigenvalue for this factor was 1.6, which explained 53% of item variance, and item factor loadings were .83, .82, and .47.

Environmental influences were operationalized by a factor score created from saving the factor yielded by two measures: social capital and social support. The eigenvalue for this factor was 1.4, which explained 68% of item variance, and factor loadings were both .82.

Regression Analysis

The question addressed by the regression analyses was whether adherence self-efficacy had a direct effect on adherence to ART or whether its effect would be mediated by cognitive and other personal factors (depressive symptoms and physical health) and environmental factors (social capital and support). It may have been the case that increased adherence self-efficacy would be associated with lower depressive symptoms and better physical health and higher social capital and support and through those pathways predict increased adherence to ART. Conversely, adherence self-efficacy may have predicted increased adherence to ART controlling for its relationship with depressive symptoms, physical health, or social capital and support.

Mediation, or a diminution of the relationship between adherence self-efficacy and adherence to ART, would be demonstrated if the partial correlation between these two variables dropped substantially, or completely, when the three potential mediators were entered as a block of predictors prior to adherence self-efficacy entering the regression model.

As a single predictor, adherence self-efficacy yielded a moderately strong relationship with adherence to ART (r = .48, p < .001). As a set of predictors, the three potentially mediating variables yielding statistically significant associations with adherence (R2 = .09, df = 3, 1,155, p < .001), with the partial correlation (pr) .09 for social support (p = .002), −.17 for depressive symptoms (p < .001), and −.07 for physical health (p = .03). In the second step of the model, adherence self-efficacy was added in Block 2 of the regression. Adherence self-efficacy largely retained its direct effect on adherence to ART, with a pr of .42 (p < .001); thus, the decrease in the strength of the association between adherence self-efficacy and adherence to ART with the potential mediators in the model was negligible. Additionally, two of the three mediators, physical health and social support, no longer retained significance. The pr for the depressive symptoms dropped from −.17 to −.10, but retained significance (p < .001). The model provided support for adherence self-efficacy as a robust predictor of ART adherence behavior, serving a partial mediating role between environmental influences and cognitive or personal factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression Model Predicting Human Immunodeficiency Virus Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy

| R2 | Partial correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | ||

| Variables entered | ||

| Social support/capital | 0.09* | 0.09** |

| Physical health | 0.07*** | |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.17* | |

| Block 2 | ||

| Variables entered | ||

| Social support/capital | ns | |

| Physical health | 0.25* | ns |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.10* | |

| Adherence self-efficacy | 0.42* | |

Note. ns = not significant.

p < .01;

p = .02;

p = .03.

Discussion

Perceived self-efficacy is associated with chronic disease self-management, although the exact nature of the relationship remains elusive (Ritter et al., 2011). Most would agree that treating depressive symptoms and increasing social capital are beneficial. However, mental health treatment may not be accessible due to health insurance limitations or the reluctance of a client to engage in addressing long-standing psychological issues. The recent worldwide recession has decreased community stability and trust and worsened individual social capital, especially in highly marginalized populations. But access to effective ART treatment is widely available to persons living in the United States and Puerto Rico through publicly supported insurance programs such as Medicaid. Nurses and other healthcare providers can focus their interventions on promoting treatment self-efficacy through evidence-based interventions such as those that use informational motivation techniques while being sensitive to the possible receptiveness of referrals for mental health and social services support, when patients are agreeable to engage these resources. Corless et al. (2012) found that the importance of regular and positive engagement with the healthcare provider could not be overstated in its contribution to both 3- and 30-day adherence with ART in an international sample.

That the environmental factors did not mediate the relationship between adherence self-efficacy and ART treatment adherence was surprising. Previous analyses have found that individual level social capital was associated with physiological and psychological health in an international sample of HIV-positive adults (Webel et al., 2012). Our data emphasize the centrality of self-efficacy in treatment adherence, and nurses can engage clients to improve those skills. While social determinants of health, such as social support and capital, may add challenges and complexity to the promotion of treatment adherence behavior of HIV-positive clients or patients, they should not be viewed as insurmountable barriers to improving this important health behavior. Rather, nurses can work with these clients or patients to improve internal factors, such as self-efficacy, to improve ART treatment adherence.

Limitations

All data were gathered through self-report. However, the large national sample size increases confidence in the validity of the findings.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Research

Interventions to improve treatment adherence have focused on a number of broad strategies (Hardy et al., 2011, McMahon et al., 2011; Parsons, Golub, Rosof, & Holder, 2007; Weiss et al., 2011); this evidence suggests that targeting treatment adherence alone may also improve ART adherence and reduce some cognitive and other personal barriers to adherence, irrespective of social capital and support. Client teaching has long been the domain of nursing practice, and this research provides evidence as to the value of ensuring that treatment self-efficacy is optimized. Simple interventions to improve treatment self-efficacy may not only impact ART adherence, but also some other, broader health-related outcomes such as health status and quality of life. ART medications reduce HIV viral load, which has a direct impact on promoting the immune status of the infected individual, but also a public health impact, since it decreases transmission of the virus from infected to uninfected persons.

Clinical Resources.

Adherence to HIV Antiretroviral Therapy: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-03-02-09

Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions: Medication Adherence Chapter: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/ma-chapter.htm

Adherence Guide for HIV/AIDS Clinical Care, HRSA HIV/AIDS Bureau June 2012: http://www.aidsed.org/aidsetc?page=cg-406adherence

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants UL1 RR024131, T32NR007081, KL2RR024990, and R15NR011130; International Pilot Award, University of Washington Center for AIDS Research; University of British Columbia School of Nursing Helen Shore Fund; Duke University School of Nursing Office of Research Affairs; Massachusetts General Hospital Institute for Health Professions; Rutgers College of Nursing; and Professional Staff Congress–City University of New York award, Hunter College, City University of New York. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or any other funders.

References

- Alvy L, McKirnan D, Mansergh G, Koblin B, Colfax G, Flores S Project MIX Study Group. Depression is associated with sexual risk among men who have sex with men, but is mediated by cognitive escape and self-efficacy. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(6):1171–1179. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Greenwich CT: Information Age Publishing; 2006. pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Corless IB, Guarino AJ, Nicholas PK, Tyer-Viola L, Kirksey K, Brion J, Holzemer WL. Mediators of antiretroviral medication adherence: A multisite international study. AIDS Care. 2012 Jul 9; doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.701723. [Epub] Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2012.701723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cunningham WE, Sohler NL, Tobias C, Drainoni ML, Bradford J, Davis C, Wong MD. Health services utilization for people with HIV infection: Comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the U.S. population in care. Medical Care. 2006;44(11):1038–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000242942.17968.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M, Lepper H, Croghan T. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J, Batchelder A, Psaros C, Safren S. Depression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2011;58(2):181–187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822d490a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy H, Kumar V, Doros G, Farmer E, Drainoni ML, Rybin D, Skolnik PR. Randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone reminder system to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(3):153–161. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(2):Article No. CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Neilands T, Dilworth S, Morin S, Remien R, Chesney M. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: Validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9118-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Kazis L, Lee A, Rogers W, Skinner K, Cassar L, Hendricks AM. Health status assessments using the Veterans SF-12 and SF-36: Methods for evaluating outcomes in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2001;24(3):68–86. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, Wilson IB. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS & Behavior. 2008;12(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M, Kuo I, Shelley K, Rawls A, Peterson J, Montanez L, Greenberg AE. Risk factors driving the emergence of a generalized heterosexual HIV epidemic in Washington, District of Columbia networks at risk. AIDS. 2009;23(10):1277–1284. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b51da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride C, Bryan A, Bray M, Swan G, Green E. Health behavior change: Can genomics improve behavioral adherence? American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(3):401–405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JH, Jordan MR, Kelley K, Bertagnolio S, Hong SY, Wanke CA, Elliott JH. Pharmacy adherence measures to assess adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Review of the literature and implications for treatment monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;52(4):493–506. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyx J, Bullen JP. Measuring social capital in five communities. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2000;36(1):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012, from http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/Adultand-AdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, Holder C. Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;46(4):43–50. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC. Antiretroviral therapy adherence: Testing a social context model among Black men who use illicit drugs. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2011;22(2):100–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu C, Raffi F, Roux P, Reynes J, Dellamonica P, Spire B, Carrieri MP. Factors associated with non-adherence to long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy: A 10 year follow-up analysis with correction for the bias induced by missing data. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2009;64(3):599–606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Nahm ES. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item short-form health survey in older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2001;9(2):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard A, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2011;43(3):255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter P, Lee J, Lorig K. Moderators of chronic disease self-management programs: Who benefits? Chronic Illness. 2011;7(2):162–172. doi: 10.1177/1742395311399127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay LE. A concept analysis: Adherence and weight loss. Nursing Forum. 2008;43(1):42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames A, Becker B, Marcotte T, Hines L, Foley J, Ramezani A, Hinkin C. Depression, cognition, and self-appraisal of functional abilities in HIV: An examination of subjective appraisal versus objective performance. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2011;25(2):224–243. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.539577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 3. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Phillips JC, Dawson-Rose C, Corless I, Voss J, Tyer-Viola L, Salata R. A cross-sectional description of social capital in an international sample of persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) BMC Public Health. 2012:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-188. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2458-12-188.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weiss SM, Tobin JN, Antoni M, Ironson G, Ishii M, Vaughn A SMART/EST Women’s Project Team. Enhancing the health of women living with HIV: The SMART/EST Women’s Project. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;15(3):63–77. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]