Abstract

Prostate cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related death in men, largely attributable to distant metastases, most frequently to bones. Despite intensive investigations, molecular mechanisms underlying metastasis are not completely understood. Among prostate cancer-derived factors, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), first discovered as an etiologic factor for malignancy-induced hypercalcemia, regulates many cellular functions critical to tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. In this study, the role of PTHrP in tumor cell survival from detachment-induced apoptosis (i.e. anoikis) was investigated. Reduction of PTHLH (encoding PTHrP) gene expression in human prostate cancer cells (PC-3) increased the percentage of apoptotic cells when cultured in suspension. Conversely, overexpression of PTHrP protected prostate cancer cells (Ace-1 and LNCaP, both typically expressing low or undetectable basal PTHrP) from anoikis. Overexpression of nuclear localization signal (NLS)-defective PTHrP failed to protect cells from anoikis, suggesting that PTHrP-dependent protection from anoikis is an intracrine event. A PCR-based apoptosis-related gene array showed that detachment increased expression of the TNF gene (encoding the proapoptotic protein tumor necrosis factor-α) fourfold greater in PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells than in control PC-3 cells. In parallel, TNF gene expression was significantly reduced in PTHrP-overexpressing LNCaP cells, but not in NLS-defective PTHrP overexpressing LNCaP cells, when compared with control LNCaP cells. Subsequently, in a prostate cancer skeletal metastasis mouse model, PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells resulted in significantly fewer metastatic lesions compared to control PC-3 cells, suggesting that PTHrP mediated antianoikis events in the bloodstream. In conclusion, nuclear localization of PTHrP confers prostate cancer cell resistance to anoikis, potentially contributing to prostate cancer metastasis.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death in males worldwide, notwithstanding the improved early detection methods and therapeutic modalities (Jemal et al. 2011). Advanced-stage prostate cancer patients commonly develop metastatic lesions, most frequently in the skeleton, which ultimately account for the high mortality rate as well as severe morbidities (Weilbaecher et al. 2011). In sharp contrast, the molecular mechanism leading to metastasis is not yet completely understood. Metastatic colonization in distant organs requires disseminating tumor cells to have essential cellular functions, such as invasion of extracellular matrices, survival in the bloodstream, extravasation, and adaptation to the new environment (Langley & Fidler 2011), which are mediated by numerous tumor-derived factors. Prostate cancer is uniquely positioned because of its strong propensity to interact with and metastasize to bone. In this regard, prostate cancer cells express numerous bone-modulating cytokines including para-thyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, and others (Deftos et al. 2005). However, contributions of these bone-modulating factors to metastasis remain under investigation.

PTHrP was first discovered as an etiologic factor for malignancy-induced hypercalcemia by increasing osteoclastogenesis (Suva et al. 1987). Later, PTHrP expression was identified in carcinoma cells, such as lung, breast, and prostate cancer cells (Moseley et al. 1987, Iwamura et al. 1993, Downey et al. 1997). Similar to its physiologic counterpart, PTH, PTHrP binds to its cognate PTH/PTHrP receptor (PPR) expressed on osteoblasts and also found in some tumor cells (Downey et al. 1997, Iddon et al. 2000), triggering the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A signal transduction pathway. In addition to autocrine/paracrine effects mediated by receptor binding, PTHrP has been shown to localize to the nucleus, leading to the inhibition of apoptosis in chondrocytes and prostate cancer cells (Henderson et al. 1995, Dougherty et al. 1999). Chondrocytes expressing PTHrP with a deletion of the nuclear localization signal (NLS) showed increased apoptosis (Henderson et al. 1995), indicating that PTHrP functions as an antiapoptotic factor. However, the potential role of PTHrP in tumor cells, particularly in the context of metastatic cascades, is under investigation. For example, tumor cells are triggered to undergo apoptosis when the cells lose attachment to their extracellular matrix, a cellular phenomenon termed anoikis. Evasion of anoikis in the metastatic process (e.g. in the bloodstream) is essential for successful colonization of tumor cells in distant organs (Sakamoto & Kyprianou 2010).

In this study, the function of PTHrP in the context of prostate cancer was examined using an in vitro anoikis model as well as an in vivo experimental bone metastasis model. PTHrP protected prostate cancer cells from anoikis, effects of which were mediated by nuclear localization of PTHrP and reduced expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Prostate tumor cells expressing lower PTHrP resulted in significantly fewer metastatic lesions compared to cells expressing higher PTHrP, potentially mediated by increased anoikis due to loss of intracrine PTHrP activity.

Materials and methods

Cells

PC-3, LNCaP, and Ace-1 prostate carcinoma cells were selected to study the function of PTHrP, because PC-3 cells express high levels of endogenous PTHrP while LNCaP and Ace-1 cells do not express detectable PTHrP. The canine prostate carcinoma cell line (Ace-1) was kindly provided by Dr Thomas Rosol (Ohio State University, USA; LeRoy et al. 2006, Thudi et al. 2011). Cells were maintained as monolayer cultures in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum and 1× penicillin/streptomycin and glutamate (all from Invitrogen). For in vivo bioluminescence imaging, luciferase-labeled PC-3 cells (designated PC-3Luc) were produced by stably transfecting a luciferase-expressing pLazarus retroviral construct as previously described (Schneider et al. 2005). In addition, PTHLH (NCBI reference number: NM_198966) gene expression was reduced in PC-3Luc cells via a lentiviral vector (pLenti4/Block-iT DEST vector; Invitrogen) expressing short hairpin RNA targeting 5′-GGGCAGATACCTAACTCAGGA-3′. An empty vector was used as a control. Lentiviral supernatants were prepared using 293T packaging cells (the University of Michigan Viral Vector Core Laboratory, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), followed by transduction of PC-3Luc cells with polybrene (6 μg/ml). Subsequently, transduced cells were grown in bleomycin selection media (Zeocin 200 μg/ml; Invitrogen), and stable clones were selected and expanded for further experiments.

LNCaP and Ace-1 cells normally express undetectable basal levels of PTHrP. Both cell lines were stably transfected with full-length PTHrP, NLS-defective PTHrP (i.e. amino acids 87–107) (Henderson et al. 1995), or empty pcDNA3.1 vectors, as previously described (Dougherty et al. 1999, Liao et al. 2008).

Measurement of PTHrP

PTHrP expression was measured from the culture supernatant using an IRMA kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX, USA), detecting amino acids 1–87 (Ratcliffe et al. 1991). Briefly, one million cells were seeded in a six-well plate in complete RPMI-1640 media (in triplicate), followed by media change with serum-free RPMI-1640 24 h later. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 48 h and cell-free supernatants collected. The PTHrP assay was performed as suggested by the manufacturer.

Calculation of in vitro doubling time

PTHrP-knockdown and empty vector control PC-3Luc cells were synchronized (by overnight serum starvation), followed by seeding (1 × 105 cells/well, in triplicate) and enumeration at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h later with the aid of a hemacytometer and trypan blue dye. The doubling time (Td) was calculated using the formula: , where Q1 and Q2 are cell numbers at two time points (T1 and T2) respectively.

In vivo tumor growth

All animal experimental protocols were approved and performed in accordance with current regulations and standards of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

For in vivo tumor growth, male athymic mice (Hsd: Athymic nude –Foxn1nu; 4 weeks old; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were anesthetized and 100 μl of cell suspension containing 1 × 106 cells were mixed with 100 μl of growth factor reduced Matrigel (Invitrogen), and injected subcutaneously into both flanks (n = 10 each group). After 3 weeks, bioluminescence imaging was performed to measure tumor size, followed by euthanasia and tumor tissue harvesting.

Anoikis assay and flow cytometry

To induce anoikis in vitro, prostate cancer cells were cultured in suspension as previously described (Minard et al. 2006). Briefly, six-well tissue culture plates were covered with 4% w/v endotoxin-free agarose. Prostate cancer cells were ~80% confluent at the initiation of overnight serum-starvation (for synchronization). Subsequently, cells were trypsinized and counted, followed by seeding of 1 × 106 cells/well in RMPI-1640 media supplemented with 2% v/v fetal bovine serum on regular culture plates or agarose-covered plates (in sextuplicate). After 12–16 h of incubation at 37 ° C, cells were harvested by pipetting (for cells in suspension) or trypsinization (for attached cells), followed by washing with ice-cold PBS and centrifugation.

For flow cytometric analyses, cells were re-suspended in Annexin V binding buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), followed by addition of FITC-conjugated anti-Annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences). Subsequently, cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and analyzed by flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur) with CellQuest analyses software (BD Biosciences).

Apoptotic gene array

PTHrP-knockdown and empty vector control PC-3Luc cells were grown on regular or 4% w/v agarose-covered 10 cm tissue culture plates (in duplicate) for 16 h. Subsequently, cells were lysed and total RNA was prepared (Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen). RNA samples were reverse transcribed (RT2 First Strand Kit; SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD, USA), followed by quantitative PCR-based human apoptotic gene array (SA Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocols (Li et al. 2011). Analyses of data were performed using computer software provided by the manufacturer. A complete list of 84 apoptosis-related genes included in the analyses, detailed protocols, and analysis method can be found at the manufacturer’s website (http://www.sabiosciences.com/rt_pcr_product/HTML/PAHS-012A.html).

In vivo metastasis model

To test the metastatic potentials of PC-3Luc clones, cells were inoculated into the systemic circulation via intracardiac route, as previously described (Park et al. 2011a), followed by in vivo bioluminescence imaging. In brief, male athymic mice (Hsd: Athymic nude –Foxn1nu; 6 weeks old; Harlan Laboratories) were anesthetized and 100 μl of cell suspension containing 2 × 105 cells were injected into the left heart ventricle. Systemic circulation of the tumor cells was confirmed by in vivo bioluminescence imaging immediately after inoculation. Metastatic hind limb tumors were detected and quantified by bioluminescence imaging (Caliper Life Sciences, Alameda, CA, USA). Tumor-bearing hind limb bones were harvested at euthanasia, fixed in 10% v/v buffered formaldehyde and decalcified in 10% w/v EDTA for 2 weeks. Metastatic tumor cells were microscopically confirmed.

Cytokines and antibodies

Recombinant human TNF-α and anti-human TNF-α neutralizing antibodies were purchased from Peprotech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). For western blotting, anti-PTHrP antibody (H-137: a rabbit polyclonal antibody against amino acids 41–177 of human PTHrP) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests were performed by Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism Version 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups and the P < 0.05 level was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided and data expressed as a mean ± S.D.

Results

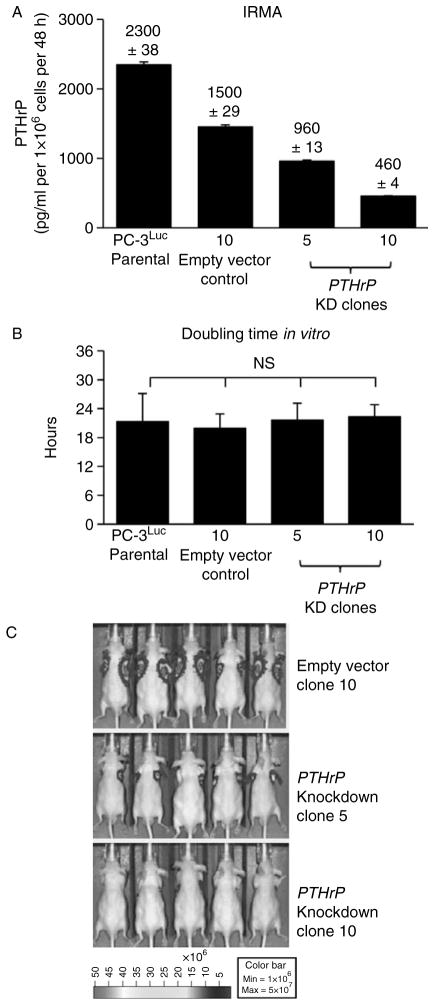

PTHrP-knockdown reduced in vivo tumor growth without affecting in vitro proliferation

As a first approach to investigate the function of PTHrP in prostate cancer cells, PTHLH gene expression was reduced in PC-3Luc human prostate cancer cells using an shRNA technique. Stable clones were confirmed and selected according to level of PTHrP expression (Fig. 1A) in the cell culture supernatants. Two knockdown clones (clone no. 5 and 10) showed more than 50% reduction of PTHrP expression compared to parental PC-3Luc cells, while an empty vector control clone also showed mild reduction, but not to the extent of clones 5 and 10. PTHrP has been shown to regulate cellular proliferation (Dougherty et al. 1999). However, cell enumeration assays demonstrated that PTHrP-knockdown did not affect in vitro cellular doubling time of PC-3Luc cells (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the reduced level of PTHrP expression was sufficient to maintain cellular proliferation, at least in PC-3Luc cells which express high basal levels of PTHrP. In contrast, PTHrP-knockdown resulted in significantly reduced tumor growth in vivo (Fig. 1C), suggesting that PTHrP regulates tumor cell proliferation and/or survival via a mechanism other than direct regulation of cell proliferation.

Figure 1.

Generation of PC-3 prostate cancer cells expressing varying levels of PTHrP. PTHrP expression was reduced in PC- 3Luc cells via lentiviral shRNA. (A) PTHrP protein levels were measured from the culture supernatant by IRMA. Data are average of two measurements ± S.D. Assays were repeated more than three times, and one set of representative data is shown. (B) In vitro doubling time of the PC-3 clones expressing varying levels of PTHrP was calculated by enumeration of viable cells at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h time points (n = 3 each). Data are mean ± S.D. NS, not significant. (C) In vivo tumor size was measured by bioluminescence imaging. Subcutaneous tumors were grown for 20 days (n = 10 per group). Five representative mice are shown. Tumor incidence was 100% in all three groups, determined by microscopic examination of tumor cells upon necropsy.

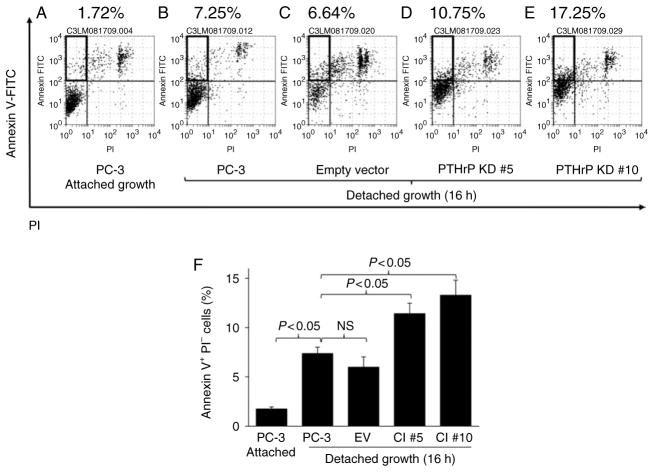

Reduction of PTHrP expression sensitized PC-3Luc cells to detachment-induced apoptosis

In routine maintenance subculturing, differential plating efficiency among PTHrP-knockdown and control clones was noted, leading to a hypothesis that PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells are more prone to detachment-induced apoptosis. To test this, PC-3Luc cells and PTHrP-knockdown clones were grown in suspension for an extended time, followed by flow cytometric analyses of apoptotic cells. Detachment increased the percentage of apoptotic Annexin V+PI− PC-3Luc cells (Fig. 2A and B), and empty vector control cells (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, PTHrP-knockdown clones had a significantly increased percentage of Annexin V+PI− apoptotic cells (Fig. 2D, E and F), indicating that reduction of PTHrP expression inhibits survival of prostate tumor cells in suspension.

Figure 2.

Reduction of PTHrP expression sensitized PC-3 cells to detachment-induced apoptosis. PC-3 cells expressing varying levels of PTHrP were induced to undergo anoikis, followed by flow cytometric analyses of apoptotic cells. Cells were seeded on regular six-well plates as a control, or on agarose-covered plates to induce anoikis (n = 6 each). (A, B, C, D and E) Representative flow cytometric dot plots are shown. Annexin V+PI− cells (marked with boxes in the upper left quadrants) indicate apoptotic cells. (F) Average percentage of apoptotic cells is shown graphically. Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant. NS, not significant.

PTHrP overexpression rescued Ace-1 prostate cancer cells from anoikis

To further investigate the role of PTHrP in anoikis, an alternative approach (i.e. ectopic expression of PTHrP) was employed. An additional prostate cancer cell line, Ace-1, had been previously shown to express undetectable levels of PTHrP (Liao et al. 2008). A PTHrP overexpression vector or empty pcDNA3.1 vector (as a control) was transfected into Ace-1 cells, resulting in Ace-1 PTHrP clone 10 and Ace-1 pcDNA respectively. PTHrP expression was measured and confirmed by IRMA of culture supernatants. The Ace-1 PTHrP clone 10 expressed 282.2 ± 9.83 (pg/ml per 1 × 106 cells per 48 h), while Ace-1 pcDNA control cells expressed undetectable levels of PTHrP. Cells were induced to undergo anoikis by culturing in suspension (Fig. 3). PTHrP overexpressing Ace-1 cells had significantly fewer apoptotic cells compared to Ace-1 pcDNA control cells (Fig. 3A, B, C and D), indicating a causal role of PTHrP in protection from anoikis.

Figure 3.

Ectopic expression of PTHrP rescued Ace-1 prostate cancer cells from anoikis. Ace-1 prostate cancer cells (expressing undetectable basal PTHrP) were engineered to express full-length PTHrP or control vector (pcDNA3.1), followed by anoikis assay. (A, B and C) Representative flow cytometric dot plots are shown. Annexin V+PI− cells (marked with boxes in the upper left quadrants) indicate apoptotic cells. (D) Average percentage of apoptotic cells is shown graphically (n = 6). Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant.

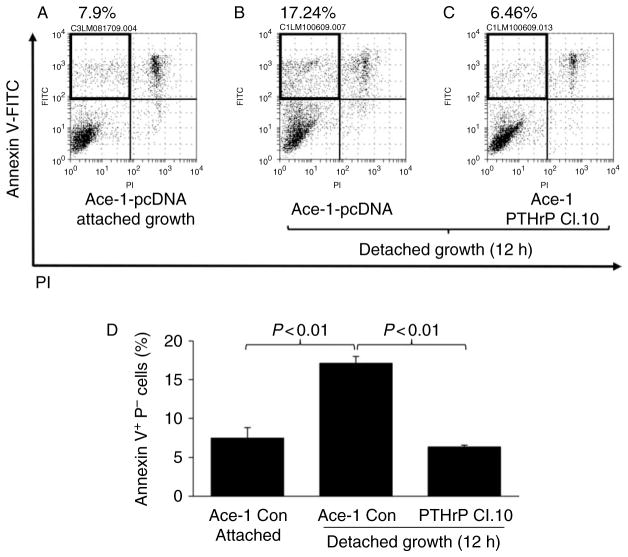

Recombinant PTHrP (1–34) failed to rescue PC-3 cells from anoikis

Data in Figs 2 and 3 demonstrated that prostate tumor cells expressing higher PTHrP have increased survival from detachment-induced apoptosis. Because PTHrP functions primarily via paracrine/autocrine manners through its cognate PTH type 1 receptor (PPR), we next tested whether exogenous PTHrP would rescue the PTHrP-knockdown clones from anoikis. Recombinant PTHrP (amino acids 1 through 34, the functional PPR-binding fragment) or conditioned media from the parental PC-3Luc cell culture which contains full-length PTHrP was added to PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 clones in suspension. Neither recombinant PTHrP (1–34) nor the conditioned media rescued PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells from anoikis (Fig. 4), suggesting that PTHrPdependent survival is not via N-terminus paracrine effects.

Figure 4.

Exogenous PTHrP failed to rescue PC-3 cells from anoikis. PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells were induced to undergo anoikis in combination with recombinant PTHrP (1–34) or conditioned media from the PC-3 cell culture, followed by flow cytometric analyses of apoptotic cells. (A, B, C, D and E) Representative flow cytometric dot plots are shown. Annexin V+PI− cells (marked with boxes in the upper left quadrants) indicate apoptotic cells. (F) Average percentage of apoptotic cells is shown. Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant. NS, not significant.

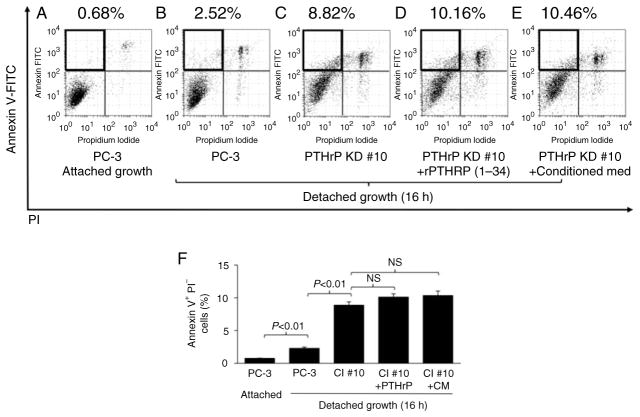

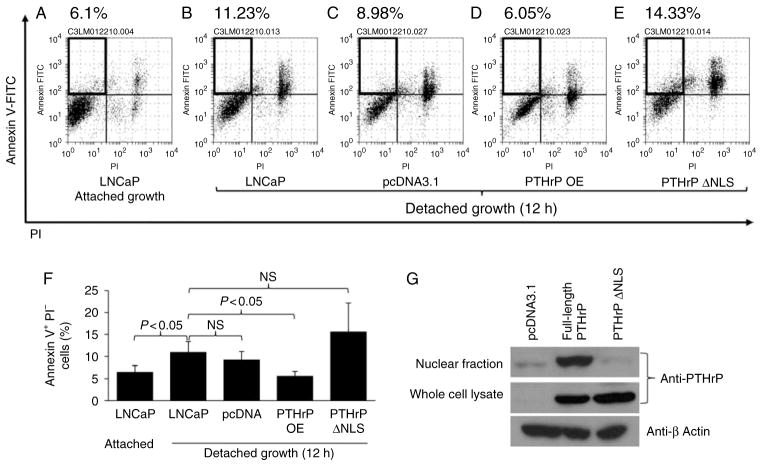

Overexpression of full-length PTHrP, but not NLS-defective PTHrP, rescues prostate cancer cells from anoikis

PTHrP localizes to the nucleus and has been shown to protect colon tumor cells from drug-induced apoptosis (Shen et al. 2007a, Bhatia et al. 2009b). Thismechanism was evaluated on PTHrP- or NLS-defective PTHrP overexpressing prostate tumor cells. Human prostate cancer cells, LNCaP, expressing undetectable basal levels of PTHrP were engineered to express full-length PTHrP (designated PTHrP OE), NLS-defective PTHrP (designated PTHrP ΔNLS), or pcDNA3.1 (as a control) (Fig. 5G). Cells were cultured in suspension to induce anoikis, followed by flow cytometric analyses. Interestingly, NLS-defective PTHrP failed to rescue LNCaP cells fromanoikis, while full-length PTHrP significantly supported LNCaP cell survival in suspension (Fig. 5A, B, C, D, E and F). Overall, Figs 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 demonstrate that PTHrP promotes prostate tumor cell survival from detachment-induced apoptosis via an intracrine manner (nuclear localization) and not a paracrine manner, potentially contributing to tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 5.

Full-length PTHrP, but not NLS-defective PTHrP, protected prostate cancer cells from anoikis. LNCaP prostate cancer cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 (control), PTHrP OE, or PTHrP ΔNLS, followed by anoikis assay. (A, B, C, D and E) Representative flow cytometric dot plots are shown. Annexin V+PI− cells (marked with boxes in the upper left quadrants) indicate apoptotic cells. (F) Average percentage of apoptotic cells is shown (n = 6). Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant. NS, not significant. (G) Western blotting analyses show high nuclear PTHrP in the PTHrP overexpressing clone and very low nuclear PTHrP in the PTHrP ΔNLS clone. Total cellular and nuclear lysates were prepared from the PTHrP OE, PTHrP ΔNLS, and pcDNA control cells, and PTHrP expression was detected by western blotting.

Detachment induced greater TNF-α expression in PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells than in empty vector control cells

To investigate downstream mediators of PTHrP-dependent anoikis, a quantitative PCR-based gene array (detecting 84 human apoptosis-related genes) experiment was performed. Detachment-induced genes were identified by comparing mRNA from cells cultured in an agarose-covered plate with cells cultured on a regular plate (columns (A) and (B) in Table 1). Among 84 apoptosis-related genes tested, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) gene expression was increased more than fourfold in PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells compared to empty vector control PC-3 cells, indicating an inverse correlation of PTHrP nuclear localization with a proapoptotic gene (TNF).

Table 1.

|

Detachment-induced genes (fold)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | (A) PTHrP-KD PC-3 | (B) EV-control PC-3 | (C) Fold changes ((A)/(B)) |

| TNF | 4.829922 | 1.182631 | 4.08 |

| CD40LG | 1.571345 | 0.547906 | 2.87 |

| BAK1 | 1.285206 | 0.693515 | 1.85 |

| TNFSF8 | 1.134455 | 0.688725 | 1.65 |

| GADD45A | 1.387031 | 0.865737 | 1.60 |

| BIRC8 | 2.891865 | 1.830198 | 1.58 |

| PYCARD | 0.612168 | 1.126619 | 0.54 |

| HRK | 1.118837 | 2.993846 | 0.37 |

| CIDEA | 0.53663 | 1.45599 | 0.37 |

| TP73 | 0.185823 | 0.890076 | 0.21 |

PC-3Luc cells were transfected with PTHLH-targeting shRNA or empty lentiviral vectors, and stable clones were selected (designated PTHrP-KD and EV-control respectively). Cells were grown on a regular tissue-culture dish (control) and on agarose-covered plate to induce anoikis. Total RNA was prepared, followed by reverse transcription and quantitative PCR apoptotic gene array. Detachment-induced genes and fold induction in PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells are shown in column (A) (i.e. detachment effects in the PTHrP-knockdown clone = detached PTHrP-KD/attached PTHrP-KD), and those in empty vector control PC-3 cells (i.e. detachment effects in the control clone = detached EV-control/attached EV-control) are shown in column (B). To identify the anoikis genes altered by PTHrP reduction, fold changes comparing PTHrP-knockdown and control PC-3 cells are shown in column (C).

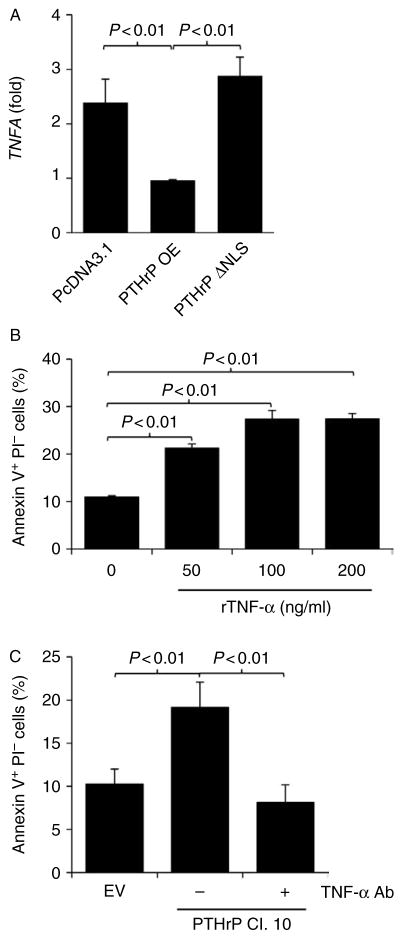

NLS-defective PTHrP failed to decrease TNF in response to detachment

To validate the observation in the gene array data (Table 1), detachment-induced TNF expression was confirmed in an additional cell line (LNCaP) expressing full-length PTHrP or NLS-defective PTHrP. Overexpression of PTHrP in LNCaP cells significantly reduced TNF gene expression, while NLS-defective PTHrP failed to do so, supporting a negative correlation between PTHLH expression and TNF (Fig. 6A). Data from Figs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and Table 1 all together demonstrated that prostate tumor cells expressing higher PTHrP have increased resistance to anoikis by suppressing a proapoptotic gene (TNF).

Figure 6.

NLS-defective PTHrP failed to decrease TNF in response to detachment. (A) LNCaP cells were transfected with empty pcDNA3.1, PTHrP OE, or PTHrP ΔNLS vectors, and stable clones were selected. Cells were grown on regular tissue-culture dishes (control) and on agarose-covered plates to induce anoikis (n = 3 each). Total RNA was prepared, followed by quantitative RT-PCR for TNF and GAPDH (for normalization). Normalized TNF gene expression from detached cells divided by normalized TNF expression from attached cells is shown graphically. Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant. (B) PC-3 empty vector control cells were seeded on agarose-covered plates to induce anoikis (n = 5 each), followed by treatment with human recombinant TNF-α (0– 200 ng/ml, as indicated). Apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometric analyses of Annexin V+PI− cells. Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant. (C) PTHrP-knockdown (clone no. 10) or empty vector control PC-3 cells were seeded on agarose-covered sixwell plates to induce anoikis (n = 5 each). Anti-human TNF-α antibody (0.6 μg/ml) was added to neutralize TNF-α in the culture supernatant. Apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometric analyses of Annexin V+PI− cells. Data are mean ± S.D. P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test was considered statistically significant.

Recombinant TNF-α promotes anoikis and neutralizing TNF-α protects cells from anoikis

The causal role of TNF-α in PTHrP-dependent anoikis was further examined. Recombinant human TNF-α administration promoted anoikis in empty vector control PC-3 cells (Fig. 6B). More importantly, neutralizing TNF-α reduced the percentage of apoptotic PTHrP-knockdown PC-3 cells in an in vitro anoikis experiment model (Fig. 6C). These results establish the causal relationship between TNF-α and PTHrPmediated anoikis in PC-3 cells.

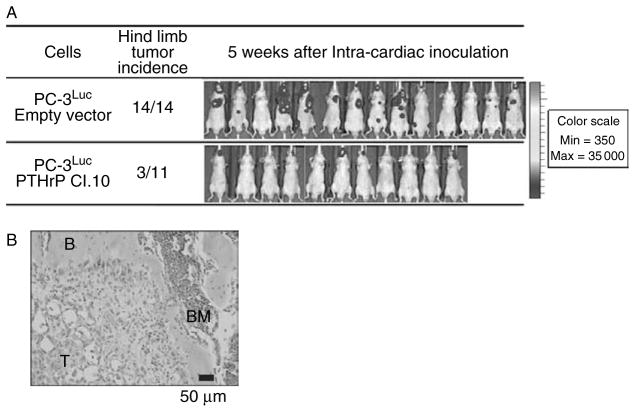

Reduction of PTHrP expression decreased prostate cancer skeletal metastasis

The biological significance of PTHrP-dependent resistance to anoikis was examined using an experimental prostate cancer skeletal metastasis model. Prostate cancer cells expressing high PTHrP were anticipated to produce more metastatic lesions via increased survival in the bloodstream, compared to prostate cancer cells expressing low PTHrP (Fig. 7). In our previous experiments, PC-3 cells develop metastatic lesions predominantly in bones (i.e. hind limbs and mandibles) in an intracardiac injection model (Schneider et al. 2005, Park et al. 2011a). Accordingly, PTHrp-knockdown or empty vector PC-3Luc cells were introduced into the systemic circulation and skeletal lesions were measured via in vivo bioluminescence imaging 5 weeks later. Because of differential in vivo growth rates (Fig. 1C), instead of comparing hind limb tumor size (quantified by photon emission from each lesion), incidence of hind limb metastatic lesions was reasoned to be a more appropriate comparison. PTHrP-knockdown PC-3Luc (clone no. 10) produced significantly fewer hind limb metastatic lesions compared to empty vector control PC-3Luc cells, potentially due to decreased survival from anoikis in the bloodstream.

Figure 7.

Reduction of PTHrP expression decreased prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. (A) PTHrP-knockdown (clone no. 10) or empty vector control PC-3Luc cells were inoculated into the systemic circulation to compare skeletal metastasis in male athymic mice (n = 14 for empty vector transfected group and n = 11 for PTHrP-knockdown clone 10 group). Development of metastatic lesions was determined by bioluminescence imaging. Hind limbs emitting more than 1× 105 photons/s were considered metastases, and mice carrying one or more metastatic hind limbs were counted and presented. There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.01 by Fisher’s exact test) in the incidence of hind limb metastatic lesions between the two groups. The whole body bioluminescence images of all mice in the experiment are shown. Note that not all metastatic lesions appear in colors, because of the normalization of pseudocoloring to the highest bioluminescence signals (mostly mandibular lesions in the control group). (B) A representative microscopic image of a metastatic lesion in the proximal tibia of PC-3Luc empty vector cells. T, tumor cells; B, bone; BM, bone marrow.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that tumor-derived PTHrP promotes prostate cancer metastasis, in part, by conferring resistance to anoikis, and that the PTHrP-dependent protection from anoikis is mediated by nuclear translocalization. Reduction of PTHrP gene expression in PC-3 luc human prostate cancer cells did not alter in vitro cellular proliferation but significantly decreased in vivo tumor growth, suggesting that PTHrP regulates cellular functions (evasion of apoptosis) in addition to previously known effects on proliferation. Indeed, PTHrP-knockdown cells had impaired ability to attach to the culture plates, leading to investigation of the mechanisms of PTHrP protection from anoikis. However, the discrepancy between in vitro proliferation and in vivo tumor growth might be attributable to other cellular functions. First, as wild-type PC-3 cells express high basal levels of PTHrP, reduction of PTHrP-expression to 20–40% (in PRHrp-knockdown clones 5 and 10) may not be sufficient to affect cellular proliferation, but enough to sensitize the cells to apoptotic stimuli. In addition, as PTHrP has been shown to regulate tumor angiogenesis (Liao et al. 2008), effects on in vivo tumor growth could simply be secondary to reduced angiogenesis. Murine endothelial cell-specific CD31/PECAM immunohistochemistry of the tumor tissue confirmed that PTHrP-knockdown tumors had significantly reduced mean vessel density (data not shown). Lastly, because PTHrP functions as a mediator in the crosstalk between the primary tumor and the bone/bone marrow, where a conducive environment is present, prostate tumors expressing low PTHrP may grow slower because of reduced recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells with tumorigenic functions (Park et al. 2011b). On the other hand, subsequent data (Figs 2, 3, 4 and 5) clearly demonstrated that PTHrP nuclear translocalization protects prostate tumor cells from anoikis, partly contributing to suppression of in vivo tumor growth of PTHrP-knockdown cells.

Antiapoptotic effects of PTHrP were first demonstrated in chondrocytes (Henderson et al. 1995), mediated by upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein BCL-2 (Amling et al. 1997). Later, PTHrP was shown to protect LoVo colon tumor cells from apoptosis by upregulating the PI3K/AKT pathway (Shen et al. 2007b). Additionally, PTHrP protected prostate tumor cells (C4-2 and PC-3) from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in an intracrine manner (Bhatia et al. 2009a), of which observations were expanded by our current study. Therefore, PTHrP-mediated protection from apoptosis can be generalized to multiple inducers of apoptosis (e.g. chemotherapy, detachment, etc.), which can account for the correlation between PTHrP expression and metastatic potential of tumor cells (Hiraki et al. 2002, Liao & McCauley 2006). Apoptosis induced by disrupted epithelial cell–matrix interactions was described by Frisch & Francis (1994), and termed ‘anoikis.’ Evasion of anoikis was reasoned, and later proved to be a critical function of metastatic tumor cells (Yawata et al. 1998, Sakamoto et al. 2010). Data from the present study expand the role of PTHrP in protecting prostate tumor cells from anoikis, leading to decreased skeletal metastasis in PTHrP-knockdown cells compared to control PC-3 cells.

Interestingly, the PCR-based gene array data demonstrated that PTHrP prevents anoikis by down-regulating the proapoptotic gene TNF, which was confirmed in an additional human prostate cancer cell line. However, the mechanism of transcriptional down-regulation by nuclear translocalization of PTHrP is unclear and requires further investigation. One potential mechanism underlying PTHrP-regulated gene expression is interaction with RNA. Aarts et al. (1999) demonstrated that nuclear PTHrP interacts with mRNA, which may lead to degradation of transcripts. Recently, deletion of mid-region, nuclear localization, and C-terminus of PTHrP (i.e. protein domains other than N-terminus which are recognized by the cognate receptor) decreases expression of genes essential for skeletal development (Runx1, Runx2 and Sox9) while increasing expression of cell cycle inhibitors (p21 and p16), supporting a role for PTHrP in transcriptional regulation (Toribio et al. 2010). Therefore, despite lack of definitive experimental evidence, nuclear localization of PTHrP may play critical roles in regulating gene expression, resulting in cellular phenotypes such as protection from apoptosis.

The current study has potential clinical significance by providing an additional molecular mechanism contributing to prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Reduction of PTHrP resulted in decreased metastatic lesions in an experimental skeletal metastasis model. Incidence of skeletal metastatic lesions in hind limbs was significantly lower than the empty vector control group, not to mention hind limb metastatic tumor size (as determined by average photon emission from metastatic lesions in each group). However, we reasoned that the comparison of tumor size between two groups may not be an adequate approach to analyze the data, because two clones (empty vector control clone and PTHrP-knockdown clone) had significantly different growth potential in vivo, thus the hind limb tumor size quantification was not included in the data. Instead, as PTHrP-knockdown cells produced significantly fewer metastatic lesions in the hind limbs compared to 100% development of hind limb metastasis in the empty vector control cells, this likely reflects the altered ability for cells to survive the trajectory from injection to tumor cell lodging and growth in bone.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates a role for PTHrP in protecting prostate tumor cells from anoikis in vitro, downregulating TNF gene expression, and supporting metastatic potential of prostate tumor cells in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was financially supported by the US Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Grants (grant numbers W81XWH-10-1-0546 (S I Park) and W81XWH-08-1-0037 (L K McCauley)); and the US National Cancer Institute Program Project Grant (grant number P01CA093900 (L K McCauley)).

The authors thank Janice E Berry, Amy J Koh, and Matthew Eber for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript, and Thomas J Rosol for providing the Ace-1 prostate cancer cells.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Author contribution statement

L K McCauley supervised all experiments and manuscript preparation. S I Park and L K McCauley designed the experiments and analyzed the data. S I Park performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Aarts MM, Levy D, He B, Stregger S, Chen T, Richard S, Henderson JE. Parathyroid hormone-related protein interacts with RNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:4832–4838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amling M, Neff L, Tanaka S, Inoue D, Kuida K, Weir E, Philbrick WM, Broadus AE, Baron R. Bcl-2 lies downstream of parathyroid hormone-related peptide in a signaling pathway that regulates chondrocyte maturation during skeletal development. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;136:205–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V, Mula RV, Weigel NL, Falzon M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein regulates cell survival pathways via integrin alpha6beta4-mediated activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling. Molecular Cancer Research. 2009a;7:1119–1131. doi: 10.1158/ 1541-7786.MCR-08-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V, Saini MK, Falzon M. Nuclear PTHrP targeting regulates PTHrP secretion and enhances LoVo cell growth and survival. Regulatory Peptides. 2009b;158:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deftos LJ, Barken I, Burton DW, Hoffman RM, Geller J. Direct evidence that PTHrP expression promotes prostate cancer progression in bone. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;327:468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty KM, Blomme EA, Koh AJ, Henderson JE, Pienta KJ, Rosol TJ, McCauley LK. Parathyroid hormone-related protein as a growth regulator of prostate carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1999;59:6015–6022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey SE, Hoyland J, Freemont AJ, Knox F, Walls J, Bundred NJ. Expression of the receptor for parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal and malignant breast tissue. Journal of Pathology. 1997;183:212–217. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199710) 183:2< 212::AID-PATH920> 3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell–matrix interactions induces apoptosis. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;124:619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb. 124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JE, Amizuka N, Warshawsky H, Biasotto D, Lanske BM, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Nucleolar localization of parathyroid hormone-related peptide enhances survival of chondrocytes under conditions that promote apoptotic cell death. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15:4064–4075. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraki A, Ueoka H, Bessho A, Segawa Y, Takigawa N, Kiura K, Eguchi K, Yoneda T, Tanimoto M, Harada M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein measured at the time of first visit is an indicator of bone metastases and survival in lung carcinoma patients with hypercalcemia. Cancer. 2002;95:1706–1713. doi: 10.1002/ cncr.10828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iddon J, Bundred NJ, Hoyland J, Downey SE, Baird P, Salter D, McMahon R, Freemont AJ. Expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein and its receptor in bone metastases from prostate cancer. Journal of Pathology. 2000;191:170–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896 (200006)191:2<170::AID-PATH620>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, Benning CM, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ, Abrahamsson PA. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormone-related protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 1993;53:1724–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited – the role of tumor–stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. International Journal of Cancer. 2011;128:2527–2535. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy BE, Thudi NK, Nadella MV, Toribio RE, Tannehill-Gregg SH, van Bokhoven A, Davis D, Corn S, Rosol TJ. New bone formation and osteolysis by a metastatic, highly invasive canine prostate carcinoma xenograft. Prostate. 2006;66:1213–1222. doi: 10.1002/pros.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Koh AJ, Wang Z, Soki FN, Park SI, Pienta KJ, McCauley LK. Inhibitory effects of megakaryocytic cells in prostate cancer skeletal metastasis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26:125–134. doi: 10.1002/ jbmr.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, McCauley LK. Skeletal metastasis: established and emerging roles of parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP) Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2006;25:559–571. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Li X, Koh AJ, Berry JE, Thudi N, Rosol TJ, Pienta KJ, McCauley LK. Tumor expressed PTHrP facilitates prostate cancer-induced osteoblastic lesions. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123:2267–2278. doi: 10.1002/ ijc.23602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard ME, Ellis LM, Gallick GE. Tiam1 regulates cell adhesion, migration and apoptosis in colon tumor cells. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2006;23:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JM, Kubota M, Diefenbach-Jagger H, Wettenhall RE, Kemp BE, Suva LJ, Rodda CP, Ebeling PR, Hudson PJ, Zajac JD, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein purified from a human lung cancer cell line. PNAS. 1987;84:5048–5052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SI, Kim SJ, McCauley LK, Gallick GE. Pre-clinical mouse models of human prostate cancer and their utility in drug discovery. Current Protocols in Pharmacology. 2011a;51Chapter 14(Unit 14):15. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1415s51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SI, Soki FN, McCauley LK. Roles of bone marrow cells in skeletal metastases: no longer bystanders. Cancer Microenvironment. 2011b;4:237–246. doi: 10.1007/ s12307-011-0081-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe WA, Norbury S, Heath DA, Ratcliffe JG. Development and validation of an immunoradiometric assay of parathyrin-related protein in unextracted plasma. Clinical Chemistry. 1991;37:678–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto S, Kyprianou N. Targeting anoikis resistance in prostate cancer metastasis. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2010;31:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mam. 2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto S, McCann RO, Dhir R, Kyprianou N. Talin1 promotes tumor invasion and metastasis via focal adhesion signaling and anoikis resistance. Cancer Research. 2010;70:1885–1895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Kalikin LM, Mattos AC, Keller ET, Allen MJ, Pienta KJ, McCauley LK. Bone turnover mediates preferential localization of prostate cancer in the skeleton. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1727–1736. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Mula RV, Evers BM, Falzon M. Increased cell survival, migration, invasion, and Akt expression in PTHrP-overexpressing LoVo colon cancer cell lines. Regulatory Peptides. 2007a;141:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep. 2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Rychahou PG, Evers BM, Falzon M. PTHrP increases xenograft growth and promotes integrin alpha6beta4 expression and Akt activation in colon cancer. Cancer Letters. 2007b;258:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j. canlet.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suva LJ, Winslow GA, Wettenhall RE, Hammonds RG, Moseley JM, Diefenbach-Jagger H, Rodda CP, Kemp BE, Rodriguez H, Chen EY, et al. A parathyroid hormone-related protein implicated in malignant hypercalcemia: cloning and expression. Science. 1987;237:893–896. doi: 10.1126/science.3616618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thudi NK, Martin CK, Murahari S, Shu ST, Lanigan LG, Werbeck JL, Keller ET, McCauley LK, Pinzone JJ, Rosol TJ. Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) stimulated prostate cancer growth and metastasis and inhibited bone formation in osteoblastic bone metastases. Prostate. 2011;71:615–625. doi: 10.1002/pros.21277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toribio RE, Brown HA, Novince CM, Marlow B, Hernon K, Lanigan LG, Hildreth BE, III, Werbeck JL, Shu ST, Lorch G, et al. The midregion, nuclear localization sequence, and C terminus of PTHrP regulate skeletal development, hematopoiesis, and survival in mice. FASEB Journal. 2010;24:1947–1957. doi: 10.1096/fj.09- 147033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilbaecher KN, Guise TA, McCauley LK. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2011;11:411–425. doi: 10.1038/nrc3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawata A, Adachi M, Okuda H, Naishiro Y, Takamura T, Hareyama M, Takayama S, Reed JC, Imai K. Prolonged cell survival enhances peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:2681–2686. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]