Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) has been widely recognized as an important cell-signaling molecule that regulates various physiological and pathological processes. S-nitrosylation, or covalent attachment of NO to protein sulfhydryl groups, is a key mechanism by which NO regulates protein functions and cellular processes. In this article we discuss the various roles of NO and protein nitrosylation in cancer development, with a focus on cell invasion and anoikis resistance, both of which are key determinants of cancer metastasis. We specially address some of the mechanisms by which NO-mediated S-nitrosylation modulates substrates that have putative effects on key steps of metastasis. We propose that nitrosothiol signaling is a key regulatory mechanism common to several pathways involved in cancer progression and metastasis, and identifying such a mechanism will improve our understanding of the disease process and aid in the development of novel anticancer therapeutics.

Keywords: nitric oxide, S-nitrosylation, cancer, metastasis, anoikis, invasion

I. INTRODUCTION

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule that functions as a messenger and effector in various biological processes.1 It is produced endogenously by NO synthases (NOSs), which exist in 3 isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS), or NOS1; inducible NOS (iNOS), or NOS2; and endothelial NOS, or NOS3.2 Expression of NOS and production of NO have been detected in various human malignant tumors, including those of the brain, breast, lung, prostate, and pancreas and have been linked to disease pathogenesis and progression.3–6 In addition to tumor cells, NO also is produced by neighboring cells, for example, endothelial cells in the microvasculature and immune cells and stromal cells in the tumors.6,7 Because of its lipophilic nature, which allows free diffusion of the molecule across cellular membranes, NO that is produced and released by neighboring cells can also exert its effects on tumor cells. The functional role of NO on tumor progression and metastasis is complex and depends on the activity, source (tumor cells or neighboring cells), and localization of NOS, as well as the concentration and duration of NO exposure, cellular context and sensitivity to NO, and tumor stage.8–10 Among the various reported factors, the level of NO is considered to be a key factor in determining the outcome of its signaling. In general, low levels of NO (<10 nM) are required to maintain physiological function in muscle and endothelial cells. The tumor-promoting role of NO, for example, tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), generally is observed at relatively low (micromolar range) but sustained levels of NO, whereas the tumor-inhibiting role of NO, for example, induction of apoptosis, is seen at acute, extremely high (millimolar range) concentrations.11,12 Several tumor-associated proteins that are targets for NO regulation have been reported,12 including proapoptotic proteins such as caspases and p53, proproliferative proteins such as p21Ras and Akt1, endothelial cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8, and various matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 (for an extensive list of proteins, see Ref. 12).

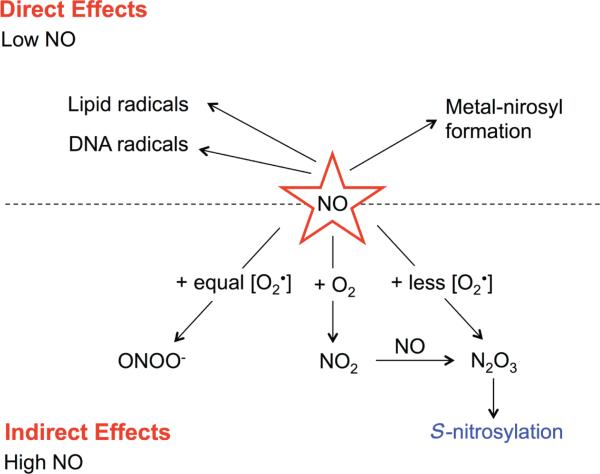

The role of NO in tumor biology may be classified into direct and indirect effects (Fig. 1). Direct effects are defined as those occurring as a result of interactions between NO and specific molecular targets, such as metals, lipids, and DNA, through free radical reactions. Indirect effects do not involve NO, but rather are mediated by reactive nitrogen-oxygen species derived from the reaction of NO with various reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to nitrosative or oxidative stress.13 Subsequently, these stresses induce post-translational modifications of proteins which affect their structure, protein-protein interactions, and functions.14

FIGURE 1.

Chemical biology of nitric oxide (NO). NO and superoxide (O2-) interact to form reactive nitrogen-oxygen species (RNOS). Generation of these RNOS depends on the redox environment and the concentrations of NO and O2-. Equal levels of NO and O2- lead to the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO-). Excess NO results in the formation of dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) and possibly S-nitrosylation. The dashed line separates the direct versus the indirect effects of NO.

In this review, we will summarize the current understanding of the role of NO in cancer metastasis with a focus on anoikis resistance and invasive properties of tumor cells. We will also specially address NO signaling and protein S-nitrosylation (described below) by discussing important substrates that have putative effects on several aspects of metastasis.

II. CHEMICAL BIOLOGY OF NITRIC OXIDE

The unique chemistry of NO allows it to participate in various biological reactions. In the inter-membrane environment, NO reacts with superoxide (O2-) to form various reactive nitrogen-oxygen species products depending on its concentration and redox microenvironment.14 For example, equivalent concentrations of NO and O2- interact to form peroxynitrite (ONOO-), which occurs predominantly at the site of O2- formation because of the more freely diffused NO compared with O2-. An excess amount of NO could lead to formation of dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3), which is the major species involved in S-nitrosylation. In addition, N2O3 is formed from the reaction of NO and O2 (autoxidation), which yields nitrogen dioxide (NO2) intermediate (Fig. 1).

In cancer cells, NO regulates a wide range of proteins through S-nitrosylation, affecting essential steps that dictate cancer phenotypes, such as cell growth and proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion.12 The principal target of cellular NO is the cysteine thiol groups of protein. Although cysteines are found abundantly in most proteins, there seems to be specificity in terms of the cysteine residues that are susceptible to nitrosylation or de-nitrosylation. The determining factors for cysteine susceptibility are hydrophobicity, electrostatic environment, orientation of aromatic residues, proximity of target thiols to the redox center, and protein-protein interactions.15–17 Because protein nitrosylation depends largely on the reactivity between the nitrosylating agent and the redox microenvironment, different sources of NO (different NOS or exogenous NO donors) could induce different S-nitrosylation profiles in the same cell type.

III. CANCER METASTASIS

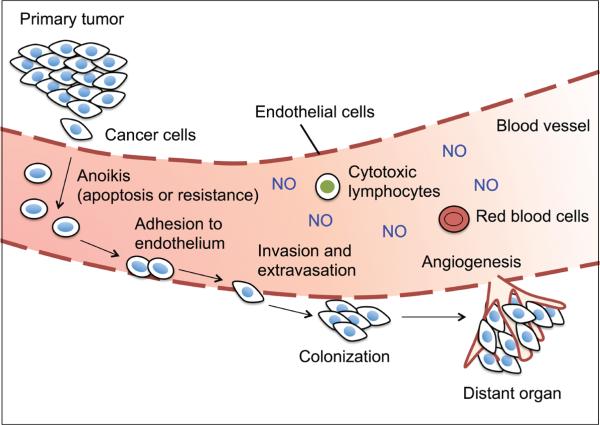

Cancer metastasis, or the capability of tumor cells to leave a primary tumor and form a secondary tumor at a distant site, is the leading cause of cancer-related death.18 It is one of the major challenges of cancer therapy and remains the most poorly understood phenomenon in cancer pathology. Metastasis is a multistep process that can be classified sequentially into 5 major steps19: (1) detachment and migration of tumor cells into the adjacent tissue; (2) invasion of the cells into blood and lymphatic circulation (intravasation); (3) survival of the cells in the circulation (anoikis resistance); (4) invasion and penetration of the cells out of the circulation (extravasation); and (5) colonization, proliferation, and angiogenesis of tumor cells at the distant sites (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Diagrammatic representation of major steps in cancer metastasis. Increased production of nitric oxide (NO) has been associated with many human metastatic tumors.

IV. PROTEIN NITROSYLATION AND ANOIKIS

Survival of a cell is dependent on its interaction with neighboring cells and the ECM. Inadequate or inappropriate interactions between a cell and its surrounding substratum leads to a disruption of cell adhesion that triggers apoptosis, which is referred to as anoikis.20 Thus, anoikis prevents detached cells, which could be potential precursors of metastatic tumor cells, from colonizing elsewhere21 and is, therefore, a critical step in determining tumor metastasis. Resistance to anoikis increases cell survival in the circulation under detachment conditions, facilitating eventual reattachment and colonization of tumor cells at secondary sites. Clinical data indicates a strong correlation between anoikis resistance in advanced cancers and poor survival of patients.22,23

Several signaling molecules have been implicated in anoikis resistance of tumor cells, including phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinase , Jun N-terminal kinases, and caveolin-1 (Cav-1).24–26 Increasing evidence has demonstrated the over-expression of Cav-1 in malignant and aggressive forms of solid tumors including prostate, bladder, colon, breast, ovarian, and lung carcinoma,27–29 but the role of Cav-1 in the regulation of anoikis recently has garnered significant attention in cancer research. Ectopic expression of Cav-1 was shown to prevent anoikis of cancer cells through various mechanisms including p53 inactivation, upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor, activation of Akt, and Mcl-1 stabilization.30–33 Our recent study further demonstrated that NO regulates Cav-1 stability and mediates tumor cell susceptibility to anoikis.34 This study, as well as those reporting S-nitrosylation of apoptosis-regulatory proteins and tumor suppressor PTEN are discussed below.

IV.A. NO and caveolin-1

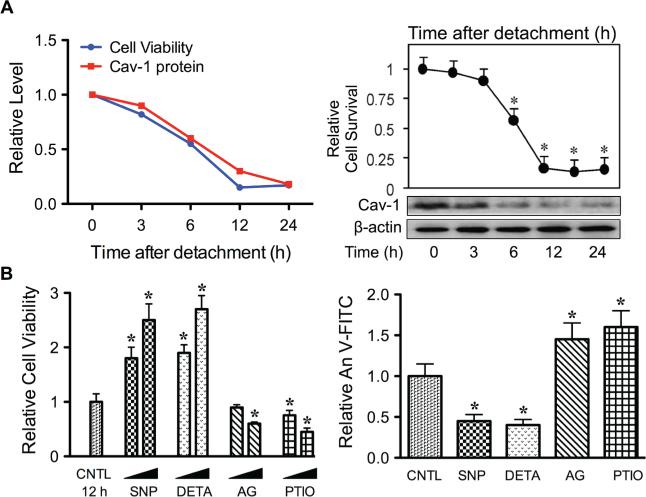

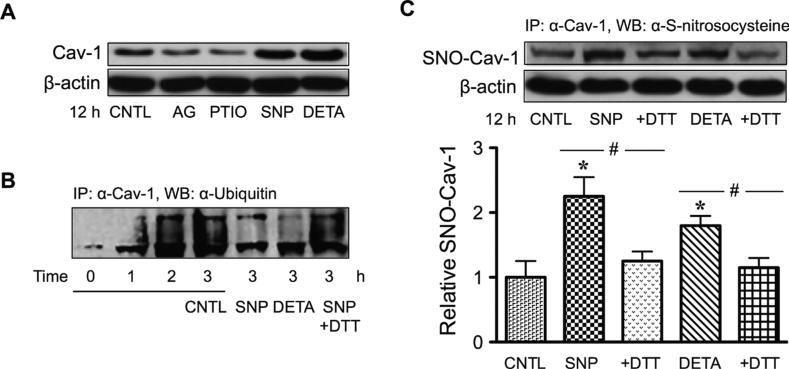

Cav-1 is an essential component of plasma membrane microdomain caveolae that has been linked to anoikis. Upon detachment of human lung cancer cells, expression of Cav-1 gradually decreased over time, with a concomitant decrease in cell survival and an increase in anoikis (Fig. 3A). In contrast, cells overexpressing Cav-1 showed resistance to anoikis, indicating the negative regulatory role of Cav-1 in anoikis. Modulation of cellular NO has a profound effect on anoikis and Cav-1 expression in these cells. For example, the NO donor diethylenetriamine (DETA) NONOate and sodium nitroprusside strongly suppressed cell anoikis, whereas the NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4, 4, 5, 5-tetramethyl-imidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide and iNOS inhibitor aminoguanidine had an opposite effect (Fig. 3B). At the concentrations that modulate anoikis, the NO donors inhibited detachment-induced Cav-1 downregulation, whereas the NO inhibitors promoted it (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, NO was found to exert its effect on Cav-1 through inhibition of protein ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these data indicate that NO promotes anoikis resistance and possibly metastasis by interfering with Cav-1 degradation. The mechanism by which NO inhibits Cav-1 degradation was found to involve protein S-nitrosylation. As shown in Fig. 4C, the NO donors sodium nitroprusside and DETA NONOate were able to induce S-nitrosylation of Cav-1. Inhibition of S-nitrosylation of Cav-1 by dithiothreitol blocked the stabilizing effect of NO on Cav-1.34 Together, these data suggest that NO negatively regulates anoikis, at least in part, through its ability to nitrosylate the protein, which prevents its downregulation via the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway.

FIGURE 3.

Role of nitric oxide (NO) in cancer cell anoikis and its regulation of Caveolin-1 (Cav-1). A: Human lung carcinoma H460 cells were detached and suspended for various times (0–24 hours), and cell survival and Cav-1 expression were determined by the XTT assay and Western blotting, respectively. Micrographs representing Hoechst 33342 nuclear staining of detached cells at 0 (left) and 12 hours (right). Apoptotic cells exhibited condensed nuclei, fragmented nuclei, or both. B: Detached cells were treated with various concentrations of the NO donors SNP (10–100 μM) and DETA NONOate (10–100 μM) and the NO inhibitors AG (100–300 μM) and PTIO (10–100 μM) for 12 hours, and cell viability and apoptosis were determined by XTT (left) and annexin V-FITC (right) assays. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus untreated control.

FIGURE 4.

S-nitrosylation of Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) by nitric oxide (NO). A: Human lung carcinoma H460 cells were detached and treated with AG (300 μM) and PTIO (100 μM) or with SNP (50 μM) and DETA NONOate (50 μM) for 12 hours, after which they were analyzed for Cav-1 expression by Western blotting. B: Effects of NO on ubiquitination of Cav-1. Detached cells were treated with SNP and DETA NONOate for 3 horus in the presence or absence of DTT (1 mM). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cav-1 antibody and the immune complex was analyzed for ubiquitin by Western blotting. C: Effects of NO on S-nitrosylation (SNO) of Cav-1. Detached cells were treated similarly with the test agents, and Cav-1 S-nitrosylation was determined by immunoprecipitation using anti-Cav-1 antibody followed by Western blotting of the immunoprecipitated protein using anti-S-nitrosocysteine antibody. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus untreated control.

IV.B. NO and Apoptosis Regulatory Proteins

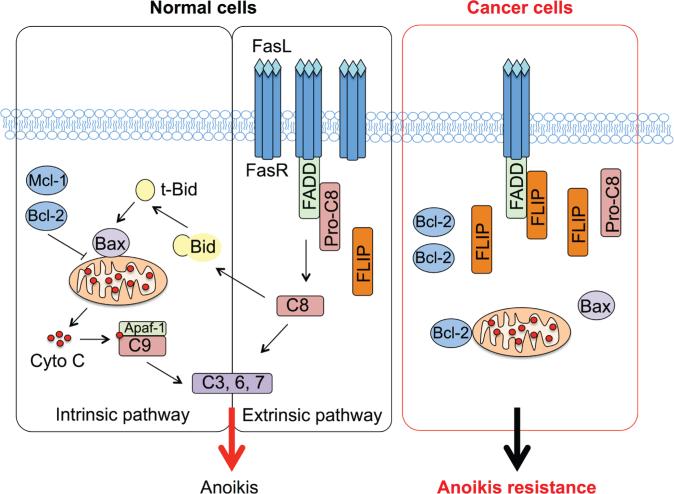

As a subset of apoptosis, anoikis also exerts its effect through the death receptor and mitochondrial death pathways (Fig. 5). The extrinsic death receptor pathway is activated when specific death ligands such as the Fas ligand and tumor necrosis factor-α bind to their membrane receptors, resulting in the formation of a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). Formation of DISC activates initiator caspases (e.g., caspase-8 or FLICE and caspase-10), which subsequently activate effector caspases (e.g., caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7), leading to the cleavage of cellular substrates. Cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) has a higher affinity for the DISC than caspase-8 and inhibits processing of caspase-8 and induction of apoptosis via the death receptor pathway at high levels of expression.35 The intrinsic mitochondrial death pathway is activated in response to a variety of death signals, leading to mitochondria depolarization, which is controlled by the balance of Bcl-2 family proteins, including antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Mcl-1 and proapoptotic proteins such as Bax, Bak, Bok, Bim, Bik, Bad, and Bid. The subsequently released cytochrome C binds to caspase adaptor molecule Apaf-1 and recruits procaspase-9 to form a complex called apoptosome. Apoptosomes then promote the for mation of effector caspases to induce apoptosis.

FIGURE 5.

Diagrammatic representation of the intrinsic mitochondrial and extrinsic death receptor pathways of apoptosis (anoikis). In cancer cells, increased expression of Bcl-2 and c-FLIP promotes anoikis resistance.

Several studies have demonstrated that malignant cells acquire anoikis resistance through an upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins such as c-FLIP36,37 and Bcl-238,39 (Fig. 5). Likewise, during the past years, the suppressive role of NO in apoptosis induced by a variety of agents, including Fas death ligand, chemotherapeutic agents, and heavy metals, has been reported through S-nitrosylation of c-FLIP and Bcl-2.40–42S-nitrosylation of these proteins prevents their downregulation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Accordingly, it has been speculated that NO might exert its antianoikis effect in part through S-nitrosylation of c-FLIP and Bcl-2. To discuss the role of S-nitrosylation in anoikis regulation further, we provide an example of our study dealing with S-nitrosylation of Bcl-2 and its regulation of the mitochondrial death pathway and anoikis resistance.

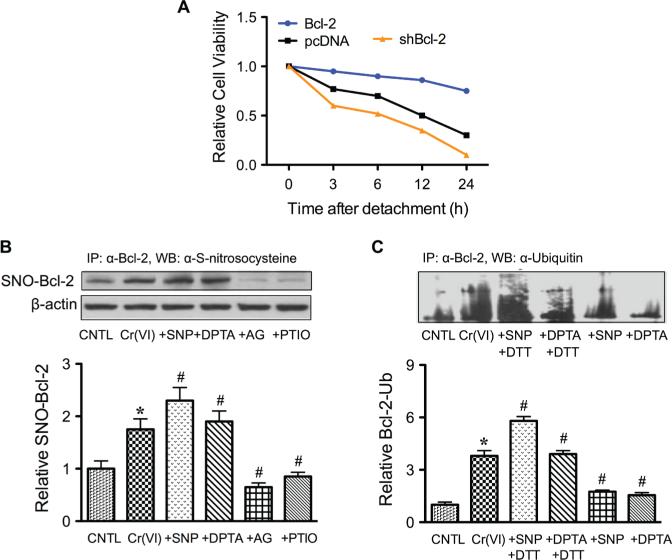

The oncogenic potential of Bcl-2 protein is well characterized, with its overexpression reported in 70% of breast cancer, 30–60% of prostate cancer, 90% of colorectal cancer, and 80% of small-cell lung cancer.43 Bcl-2 was reported to be a key modulator of anoikis resistance in osteosarcoma and pancreatic cancer.38,39 Our recent study of human lung carcinoma cells demonstrated that ectopic expression of Bcl-2 rendered the cells resistant to anoikis.44 In contrast, downregulation of Bcl-2 by siRNA reversed the anoikis resistance (Fig. 6A). Bcl-2 was found to be downregulated through ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation, and NO inhibited this degradation.41,42 The role of S-nitrosylation in the regulation of Bcl-2 was demonstrated in human lung cancer cells treated with carcinogenic metal chromium (VI) [Cr(VI)]. Figure 6B shows that Cr(VI) induced S-nitrosylation of Bcl-2 and that this effect was enhanced by NO donors and inhibited by NO inhibitors. Through site-direct mutagenesis, it was demonstrated that Bcl-2 S-nitrosylation occurred at the cysteine 158 and 229 residues. Inhibition of S-nitrosylation by dithiothreitol inhibited the effect of NO on Bcl-2 ubiquitination (Fig. 6C). Together, these results indicate that NO, through its ability to nitrosylate Bcl-2, interferes with the ubiquitination and degradation process of Bcl-2.

FIGURE 6.

Role of Bcl-2 in cancer cell anoikis and its regulation by nitric oxide (NO). A: Human lung carcinoma H460 cells were stably transfected with Bcl-2 or siRNA plasmid. The cells were detached and suspended for various times (0–24 hours) and cell survival was determined by XTT assay. B: Effects of NO on Bcl-2 S-nitrosylation. H460 cells overexpressing Bcl-2 were either left untreated or pretreated with SNP (500 μg/ml), DTA NONOate (400 μM), AG (300 μM), or PTIO (300 μM) for 1 hour and then treated with Cr(VI) (20 μM) for 3 hours. Cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated by anti-Bcl-2 antibody and the immune complexes were analyzed for S-nitrosocysteine. C: Effects of NO on Bcl-2 ubiquitination. Cells were treated similarly with SNP or DPTA NONOate in the presence or absence of DTT (1 mM). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Bcl-2 antibody and the immune complexes were analyzed for ubiquitin by Western blotting. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

IV.c. NO and PTEN

Abnormal regulation of phosphatases/kinases, including PI3K/Akt, activates prosurvival signaling and suppresses anoikis.45 PTEN, a phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10, negatively regulates the PI3K/Akt pathway. Reduced expression or complete inactivation of PTEN by mutation and deletion is found in many forms of cancers, including glioblastoma, prostate, lung and breast carcinoma, and is associated with cancer cell resistance to anoikis.46,47 Recent evidence suggests that NO signaling and S-nitrosylation regulate PTEN inactivation.48 The physiological NO donor S-nitrosocysteine induces S-nitrosylation of PTEN and leads to its concomitant ubiquitination in cultured neurons, suggesting that the NO signal induces degradation of PTEN by an ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway through protein S-nitrosylation. Although the study was conducted in neurons and not in cancer cells, it demonstrates a regulatory mechanism that may account for the frequently observed loss of PTEN in tumors.

V. PROTEIN NITROSYLATION AND CELL MOTILITY

Cell migration and invasion are the rate-limiting steps of cancer metastasis. To enter lymphatic and blood vessels for dissemination into the circulation, tumor cells must overcome certain barriers including (1) the epithelial basement membrane, (2) the stromal ECM, and (3) the vascular basement membrane.49 At any given time, only a small proportion of tumor cells are invading and disseminating. A number of direct and indirect studies suggest that increased production of NO drives the migration and invasion of these tumor cells through the regulation of multiple proteins. We focus here on the regulatory proteins that, when nitrosylated, affect cancer cell motility.

V.A. NO and caveolin-1

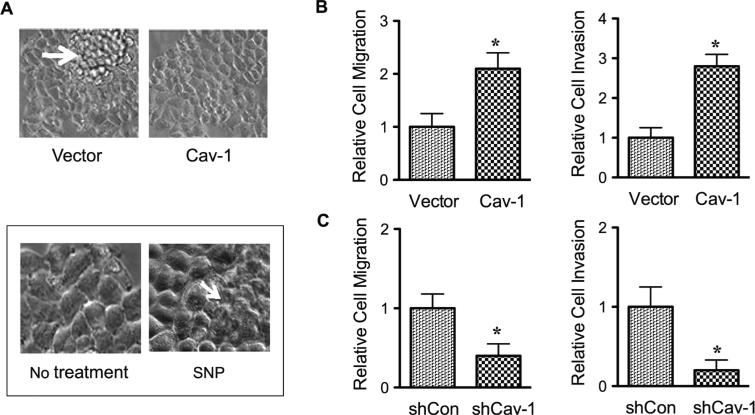

As mentioned earlier, upregulation of Cav-1 by NO-mediated S-nitrosylation is a key mechanism of anoikis resistance in cancer cells. Under normal growth conditions, NO and Cav-1 promote multilayer growth of lung cancer cells (Fig. 7A). Because cell mounding and formation of multilayers of cells is a characteristic of malignancy, this finding suggests that NO promotes malignant transformation through Cav-1 upregulation, although other molecular targets are likely involved. Cav-1 was further shown to regulate cancer cell migration and invasion.50 Ectopic expression of Cav-1 promotes cancer cell migration and invasion (Fig. 7B), whereas knockdown of Cav-1 inhibits the invasive migration (Fig. 7C). Because Cav-1 is subjected to NO regulation, it is likely that S-nitrosylation of Cav-1 is a key mechanism that controls cancer cell invasion, and thus metastasis.

FIGURE 7.

Nitric oxide (NO) promotes malignant transformation and cancer cell invasion through the upregulation of Caveolin-1 (Cav-1). A: Human lung carcinoma H460 cells were stably transfected with Cav-1 or control plasmid. The morphology of control and Cav-1 transfected cells in culture is shown in the upper panel. In the lower panel, the morphology of cells treated with SNP (50 μM) is shown. B and C: H460 cells were stably transfected with Cav-1 or siRNA plasmid. Cell migration (left) and invasion (right) were evaluated by both the wound healing and Transwell invasion assays at 24 hours. Data are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05 versus untreated control”.

V.B. NO and c-Src

Cellular Src (c-Src) is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that consists of 3 distinct functional regions: an N-terminal region, central SH3 and SH2 domains, and a catalytic tyrosine kinase domain. Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of cysteine residues in the C-terminus of the catalytic domain.51 Cysteines 483, 487, 496, and 498 are clustered in the C-terminus of c-Src, which is known to promote cancer cell invasion and metastasis in several human cancers including colon, breast, pancreas, and brain.52 It is interesting that c-Src can be acti vated by stimulation of NO.53,54S-nitrosylation of c-Src at cysteine 498 mediates its tyrosine kinase activity and cell migration in fibroblasts. In breast cancer cells, Rahman et al54 showed that β-estradiol stimulates endothelial NOS expression and NO production. S-nitrosylation of c-Src at cysteine 498 by β-estradiol was shown to disrupt E-cadherin junctions and cell-cell contact and enhance cell invasion in MCF-7 cells. These data provide a functional link between NO and Src family kinases and cancer cell invasion through protein S-nitrosylation.

V.c. NO and Ras

The prototypical Ras proteins are H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-ras4A/4B. All Ras proteins are associated with the inner face of plasma membrane, where they function to facilitate cellular signal transduction initiated by diverse extracellular stimuli. Ras signaling generally is involved in cell growth, differentiation, and survival.55,56 Thus, aberrant activation of Ras signaling can ultimately lead to cancer. Ras is one of the most common human oncogenes, and its mutations are found in approximately 30% of all human cancers. Ectopic expression of Ras in noncancer cells leads to increased cell invasion and acquisition of metastatic phenotype.55 Lim et al57 reported the requirement of H-Ras S-nitrosylation at cysteine 118 in tumor growth. Knockdown of wild-type H-Ras in the oncogenic K-ras–driven pancreatic tumor cell line CFPac1 reduced the growth of tumor xenograft in immunocompromised mice, an effect that may be rescued by wild-type H-Ras but not cysteine 118 mutant H-Ras. In contrast, Raines et al58 demonstrated that S-nitrosylation of H-Ras at cysteine 118 is sufficient to block oncogenically mutated H-Ras activity and disrupt the activation of Raf-1 and propagation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in N293 cells whose intracellular NO production is regulated by nNOS. This finding contradicts several other studies that described the promoting role of NO in cancer invasion. However, the observed inhibitory role of NO may be specific to nNOS-generated NO because the cellular effects of NO are dependent on its source.

V.d. NO and c-FLIP

c-FLIP is an endogenous inhibitor of the extrinsic death-receptor pathway and is widely expressed in various tumors. The role of c-FLIP in apoptosis and anoikis regulation has been well documented.59 Increasing evidence has indicated the role of c-FLIP in the regulation of cancer cell motility. For example, downregulation of c-FLIP by siRNA was shown to impair cancer cell migration and invasion in human cervical cancer HeLa cells.60 Previous studies by our group demonstrated that c-FLIP is nitrosylated at cysteine 254 and 259 in the caspase-like domain.40 Such S-nitrosylation interferes with the ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation process that results in increased expression of the protein, supporting the promigratory role of c-FLIP.

V.E. NO and MMP-9

Penetration of tumor cells through the basement membrane and ECM is a crucial step in tumor cell invasion and metastasis.49 MMPs are responsible for the degradation of the ECM. MMP-9 is among the gelatinases that efficiently degrade native collagen types IV and V, fibronectin, entactin, and elastin and has been implicated in tumor cell invasion.61 Localization of NOS has been shown to determine the site of protein S-nitrosylation.62 In trophoblasts for instance, MMP-9 is nitrosylated and colocalized with iNOS at the leading edges of the migrating cells, where NO production takes place.63 Because MMP-9 activation involves S-nitrosylation, it has been suggested that S-nitrosylation of MMP-9 is the key mechanism responsible for the enhanced migration and invasion of trophoblasts. MMP-9 expression is associated with cancer cell invasion and is elevated in various solid malignancies, including breast, bladder, and colon cancers.64 In addition, increased production of NO has been associated with many invasive tumors. Therefore, it is possible that NO promotes tumor cell invasion through S-nitrosylation of MMP-9.

VI. CONCLUSION

Protein S-nitrosylation has emerged as an important posttranslational modification process similar to protein phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Because it controls the activity and function of a large number of important proteins, dysregulation of protein S-nitrosylation can have a major impact on the pathogenesis of several diseases whose etiology is dependent on the abnormal regulation of NO, including cancer. NO may play a promoting or inhibitory role in cancer development, depending on its concentration, source of NO production, and the presence of other cofactors. This suggests that a broad-spectrum drug that acts as an activator or inhibitor of NO may not be effective against cancers. Considerable efforts have been made over the years to develop therapeutic strategies that target S-nitrosylated proteins in cancer. However, limited progress has been made because of the lack of detailed mechanistic understanding of the nitrosylation process and its dysregulation in cancer. Increasing evidence suggests that several proteins that are important in cancer cell invasion and anoikis are regulated by S-nitrosylation. Because invasion and anoikis resistance are key elements of cancer metastasis, understanding the mechanisms by which these proteins are abnormally regulated through S-nitrosylation will have important implications for cancer pathogenesis and the treatment of metastatic cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL095579.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cav-1

caveolin-1

- c-FLIP

cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein

- Cr(VI)

hexavalent chromium

- c-Src

cellular Src

- DISC

death-inducing signaling complex

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- iNOS (NOS2)

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinease

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS (NOS1)

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

REFERENCES

- 1.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:875–878. doi: 10.1042/bst0240875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomsen LL, Miles DW, Happerfield L, Bobrow LG, Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthase activity in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:41–44. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puhukka A, Kinnula V, Napankangas U, Saily M, Koistinen P, Paakko P, Soini Y. High expression of nitric oxide synthases is a favorable prognostic sign in non-small cell lung carcinoma. APMIS. 2003;111:1137–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2003.apm1111210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakshi A, Nag TC, Wadhwa S, Mahapatra AK, Sarkar C. The expression of nitric oxide synthases in human brain tumours and peritumoral areas. J Neuro Sci. 1998;155:196–203. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:521–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse GM, Wong FC, Tsang AK, Lee CS, Lui PC, Lo AW, Law BK, Scolyer RA, Karim RZ, Putti TC. Stromal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression correlates with the grade of mammary phallodes tumour. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:600–604. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mocellin S, Bronte V, Nitti D. Nitric oxide a double edged sword in cancer biology: searching for therapeutic opportunities. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:317–352. doi: 10.1002/med.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heigold S, Sers C, Bechtel W, Ivanovas B, Schafer R, Bauer G. Nitric oxide mediates apoptosis induction selective in transformed fibroblasts compared to non-transformed fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:929–941. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Donzell D, Espey MG, Roberts DD, Wink DA, Isenberg JS. The biphasic nature of nitric oxide in carcinogen-esis and tumour progression. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng R, Glynn S, Flores-Santana W, Switzer C, Ridnour L, Wink DA. Chapter 5 – Nitric oxide and redox inflammation in cancer. Adv Mol Toxicol. 2010;4:157–182. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer AKV, Azad N, Wang L, Rojanasakul Y. S-nitrosylation. How cancer cells say NO to cell death. In: Benjamin B, editor. Nitric Oxide (NO) and Cancer, Prognosis, Prevention and Therapy. Springer; New York: 2010. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DD, Ridnour LA, Isenberg JS, Flores-Santana W, Switzer CH, Donzelli S, Hussain P, Vecoli C, Paolocci N, Ambs S, Colton CA, Harris CC, Roberts DD, Wink DA. The chemical biology of nitric oxide: implications in cellular signaling. Free Radi cBiol Med. 2008;45:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leon L, Jeannin JF, Bettaieb A. Post-translational modifications induced by nitric oxide (NO): implications in cancer cells apoptosis. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamler JS, Lamas S, Fang FC. Nitrosylation. The prototypic redox-based signaling mechanism. Cell. 2001;78:931–936. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane P, Hao G, Gross SS. S-nitrosylation is emerging as a specific and fundamental posttranslational protein modification: head-to-head comparison with O-phosphorylation. Sci STKE. 2001;86:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.86.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidler I. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisch SM, Screaton RA. Anoikis mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson CD, Anyiwe K, Schimmer AD. Anoikis resistance and tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2008;272:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D, Weiberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakamoto S, Kyprianou N. Targeting anoikis resistance in prostate cancer metastasis. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YJ, Kuo CD, Tsai YM, Yu CC, Wang GS, Liao HF. Norcantharidin induces anoikis through Jun-N-terminal kinase activation in CT26 colorectal cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:55–64. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f18826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dufour G, Demers MJ, Gagne D, Dydensborg AB, Teller IC, Bouchard B, Degongre I, Beaulieu JF, Cheng JQ, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Vallee K, Vachon PH. Human intestinal epithelial cell survival and anoikis. Differentiation state-distinct regulation and roles of protein kinase B/Akt isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44113–44122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins NL, Reginato MJ, Paulus JK, Sgroi DC, Joshua L, Brugge JS. G1/S cell cycle arrest provides anoikis resistance through Erk-mediated Bim suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5282–5291. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5282-5291.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang G, Truong L, Timme TL, Ren C, Wheeler TM, Park SH, Nasu Y, Bangma CH, Kattan MW, Scardino PT, Thompson TC. Elevated expression of caveolin is associated with prostate and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1873–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho CC, Huang PH, Huang HY, Chen YH, Yang PC, Hsu SM. Up-regulated caveolin-1 accentuates the metastasis capability of lung adenocarcinoma by inducing filopodia formation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1647–1656. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patlolla JM, Swamy MV, Raju J, Rao CV. Overexpression of Caveolin-1 in experimental colon adenocarcinomas and human colon cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2004;115:719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravid D, Maor S, Werner H, Liscovitch M. Caveolin-1 inhibits anoikis and promotes survival signaling in cancer cells. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2006;46:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravid D, Moar S, Werner H, Liscovitch M. Caveolin-1 inhibits cell detachment-induced p53 activation and anoikis by upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and signaling. Oncogene. 2005;17:1338–1347. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Ren CH, Tahir SA, Ren C, Thompson TC. Caveolin-1 maintains activated Akt in prostate cancer cells through scaffolding domain binding site interactions with and inhibition of serine/threonine protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9389–9404. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9389-9404.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chunhacha P, Pongrakananon V, Rojanasakul Y, Chanvorachote P. Caveolin-1 regulates Mcl-1 stability and anoikis in lung carcinoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C1284–C1292. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00318.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chanvorachote P, Nimmannit U, Lu Y, Talbott S, Jiang BH, Rojanasakul Y. Nitric oxide regulates lung carcinoma cell anoikis through inhibition of ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28476–28484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guicciardi ME, Gores GJ. Life and death by death receptors. FASEB J. 2009;23:1625–1637. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YN, Koo KH, Sung JY, Yun UJ, Kim H. Anoikis resistance: an essential prerequisite for tumor metastasis. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:306879. doi: 10.1155/2012/306879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mawji IA, Simpson CD, Hurren R, Gronda M, Williams MA, Filmus J, Jonkman J, Da Costa RS, Wilson BC, Thomas MP, Reed JC, Glinsky GV, Schimmer AD. Critical role for Fas-associated death domain-like interleukin-1-converting enzyme-like inhibitory protein in anoikis resistance and distant tumor formation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:811–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dingsheng L, Jie F, Weishan C. Bcl-2 and caspase-8 related anoikis resistance in human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph MG, Melinda MM, Tawnya LB, Subbulakshmi V, Richard JB. ERK/BCL-2 Pathway in the resistance of pancreatic cancer to anoikis. J Surg Res. 2009;152:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chanvorachote P, Nimmannit U, Wang L, Stehlik C, Lu B, Azad N, Rojanasakul Y. Nitric oxide negatively regulates Fas CD95-induced apoptosis through inhibition of ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of FLICE-inhibitory protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42044–42050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chanvorachote P, Nimmannit U, Stehlik C, Wang L, Jiang BH, Ongpipatanakul B, Rojanasakul Y. Nitric oxide regulates cell sensitivity to cisplatin-induced apoptosis through S-nitrosylation and inhibition of Bcl-2 ubiquitination. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6353–6360. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azad N, Vallyathan V, Wang L, Tantishaiyakul V, Stehlik C, Leonard SS, Rojanasakul Y. S-nitrosylation of Bcl-2 inhibits its ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. A novel antiapoptotic mechanism that suppresses apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34124–34134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iyer AKV, Azad N, Wang L, Rojanasakul Y. Role of S-nitrosylation in apoptosis resistance and carcinogenesis. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pongrakhananon V, Nimmannit U, Luanpitpong S, Rojanasakul Y, Chanvorachote P. Curcumin sensitizes non-small-cell lung cancer anoikis through reactive oxygen species-mediated Bcl-2 downregulation. Apoptosis. 2010;15:574–585. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinoistide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollander MC, Blumenthal GM, Dennis PA. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:289–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vitolo MI, Weiss MB, Szmacinski M, Tahir K, Waldman T, Park BH, Martin SS, Weber DJ, Bachman KE. Deletion of PTEN promotes tumorigenic signaling, resistance to anoikis, and altered response to chemotherapeutic agents in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2875–2883. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwak YD, Ma T, Diao S, Zhang X, Chen Y, Hsu J, Lipton SA, Masliash E, Xu H, Liao FF. NO signaling and S-nitrosylation regulate PTEN inhibition in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:49. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bravo-Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luanpitpong S, Talbott S, Rojanasakul Y, Nimmannit U, Pongrakhananon V, Wang L, Chanvorachote P. Regulation of lung cancer cell migration and invasion by reactive oxygen species and caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38832–38840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giannoni E, Buricchi B, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Intracellular reactive oxygen species activate Src tyrosine kinase during cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6391–6403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6391-6403.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:5636–5642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akhand AA, Pu M, Senga T, Kato M, Suzuki H, Miyata T, Hamaguchi M, Nakashima I. Nitric oxide controls Src kinase activity through a sulfhydyl group modification-mediated Tyr-527-independent and Tyr-416-linked mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25821–25826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman MA, Senga T, Ito S, Hyodo T, Hasegawa H, Hamaguchi M. S-nitrosylation at cysteine 498 of c-Src tyrosine kinase regulates nitric oxide-mediated cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3806–3814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campbell PM, Der CJ. Oncogenic Ras and its role in tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Sem Cancer Biol. 2004;14:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kashatus DF, Counter CM. A role for eNOS in oncogenic Ras-driven cancer. In: Bonvanida B, editor. Nitric Oxide (NO) and Cancer: Prognosis, Prevention, and Therapy (Cancer Drug Delivery and Development) Springer; New York: 2010. pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lim KH, Ancrile BB, Kashatus DF, Counter CM. Tumor maintenance is mediated by eNOS. Nature. 2008;452:646–649. doi: 10.1038/nature06778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raines K, Cao GL, Lee EK, Rosen GM, Shapiro P. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase-induced S-nitrosylation of H-Ras inhibits calcium ionophore-mediated extracellular-signal-regulated kinase activity. Biochem J. 2006;397:329–336. doi: 10.1042/BJ20052002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iyer AK, Azad N, Talbot S, Stehlik C, Lu B, Wang L, Rojanasakul Y. Antioxidant c-FLIP inhibits Fas ligand-induced NF-κB activation in a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2011;187:3256–3266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shim E, Lee YS, Kim HY, Jeoung D. Down-regulation of c-FLIP increases reactive oxygen species, induces phosphorylation of serine/threonine kinase Akt, and impairs motility of cancer cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen JH, Lin HH, Chiang TA, Hsu JD, Ho HH, Lee YC, Wang CJ. Gaseous nitrogen oxide promotes human lung cancer cell line A549 migration, invasion, and metastasis via iNOS-mediated MMP-2 production. Toxicol Sci. 2008;106:364–375. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwakiri Y, Satoh A, Chatterjee S, Toomre DK, Chalouni CM, Fulton D, Groszmann RJ, Shah VH, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthase generates nitric oxide locally to regulate compartmentalized protein S-nitrosylation and protein trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19777–19782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605907103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roomi MW, Monterrey JC, Kalinovsky T, Rath M, Niedzwiecki A. Patterns of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1323–1333. doi: 10.3892/or_00000358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Z. Protein S-nitrosylation and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012;320:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]