Abstract

Background/Objectives

To quantify the occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI) occurring in the early postoperative period following surgical hip fracture repair and estimate the impact on one-year mortality.

Design

This study is a population-based, historical cohort study of patients who underwent surgical repair of a hip fracture. This studyutilized the computerized medical record linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project.

Setting

Academic and community hospitals, outpatient offices and nursing homes in Olmsted County, Minnesota.

Participants

In the 15-year study period (1988–2002), 1116 elderly patients underwent surgical repair of a hip fracture.

Measurements

At the end of the first seven days following hip fracture repair, patients were classified into one of three groups: clinically verified MIs (cv-MI), subclinical myocardial ischemia (sc-MI) and no myocardial ischemia. One-year mortality was compared between these groups. Multivariate models assessed risk factors for early postoperative cv-MI and one-year mortality, respectively.

Results

Within the first seven days following hip fracture repair, 116 (10.4%) patients experienced cv-MIs and 41 (3.7%) had sc-MIs. Overall 1-year mortality rate was 22% and there was no difference between those with sc-MIs and those with nomyocardial ischemia. One-year mortality for those with cv-MI was significantly higher than the other two groups (35.8%). Occurrence of early postoperative cv-MI, male gender, and histories of heart failure or dementia were independently associated with increased one-year mortality; while, pre-fracture home residence and preoperative higher hemoglobin were protective.

Conclusion

Early postoperative, clinically verified, MIs following hip fracture repair exceeds rates following other major orthopedic surgeries and is independently associated with increased one-year mortality.

Keywords: Hip Fracture, Myocardial Infarction, Mortality, Geriatric, Postoperative Complications

INTRODUCTION

Hip surgery (either internal fixation of a fracture or total hip arthroplasty) is the most common non-cardiac major surgical procedure performed in patients age 65 years or older, with an annual incidence of 45 per 100,000 patients.1 Although some studies have described a slight decrease in the incidence of hip fractures since 1997,2 the upcoming changing demographics of the baby boom generation and poor clinical outcomes, common after fragility fractures of the hip, will threaten to overwhelm the medical system.3 Patient morbidity during recovery after hip fracture repair can be minimized with alternative inpatient medical care models,4 yet one-year mortality rates still often exceed 20%.5–9 Prior research links the high degree of fragility and preoperative medical morbidity in this population to excess mortality postoperatively.10–13

Postoperative medical complications such as a pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary infection confer an increased risk of mortality following hip fracture repair.9, 14, 15 Less is known about the frequency or impact of postoperative myocardial infarction (MI) on survival outcomes. Approximately 30% of hip fracture patients will have an elevated troponin level within the first three days after surgery.16–18 This evidence of myocardial ischemia can be associated with increased mortality, but true MI incidence rates, based upon population-based epidemiologic data, have not been generated to assist interpretation of these outcomes.18

Contrary to these clinical outcomes, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care in Non-cardiac Surgery guidelines estimate the risk of a postoperative cardiac complication following major orthopedic procedures to be <5%.19 But with one-year recorded mortality exceeding 20% in patients sustaining hip fractures, it is difficult to reconcile the ACC/AHA theoretical risk of adverse cardiac events to the clinical outcomes associated with this traumatic event. This research effort was initiated to analyze population-based data to understand this apparent dissidence in described cardiac risk. Beginning with the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (UDMI)20 as a case definition, we further evaluated the medical record for clinical agreement with these ischemic criteria to differentiate between those with clinically verified MI (cv-MI) and isolated subclinical myocardial ischemia (sc-MI). The authors hypothesized that contrary to available preoperative guidelines, the occurrence of cv-MI after the surgical repair of hip fracture is greater than 5%. The study will determine for a county-wide population: (1) the rate of early postoperative cv-MI within the first seven days of surgical repair of hip fractures; and (2) the relationship of postoperative cv-MI, sc-MI and survival.

METHODS

Case ascertainment

Clinical data regarding patients with hip fractures, surgical intervention and postoperative MIs were identified for the population within all three hospitals of Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a county-wide computerized medical record linkage system. The Rochester Epidemiology Project enables the recording of all diagnoses and procedures for hospital, emergency room, outpatient, and nursing home care as well as laboratory and death data within Olmsted County, Minnesota.21 Following approval by Mayo Clinic’s and Olmsted Medical Center’s Institutional Review Boards, this data system was used to identify all residents who had provided prior consent for medical record review, sustained a hip fracture and undergone surgical repair between January 1, 1988 and December 31, 2002.22 The determination of hip fracture episodes in all county hospital facilities was accomplished in three phases. First, all patient hospitalizations with the following surgical procedure (ICD-9) codes were identified: 81.51 (total hip replacement), 81.52 (partial hip replacement), 81.53 (revision hip replacement), 79.15 (reduction, fracture, femur, closed with internal fixation), 79.25 (reduction, fracture, femur, open, without internal fixation), 79.35 (reduction, fracture, femur, open with internal fixation), 80.05 (arthrotomy for removal of hip prosthesis), 80.15 (arthrotomy, other, hip), 79.95 (operation, unspecified bone injury, femur), 80.95 (excision, hip joint), 81.21 (arthrodesis, hip), and 81.40 (repair hip, not elsewhere classified). Second, thorough review of each patient’s chart verified clinical documentation of a fracture associated with the indexed hospitalization. Finally, radiology reports of each indexed hospitalization were reviewed to verify presence and determine anatomical fracture location. Only patients with a proximal femur (femoral neck or subtrochanteric) fracture as the primary indication for the surgery were included in the study. Surgical reports or radiographic evidence of fracture were available for all patients. Patients treated nonoperatively were excluded. For patients with more than one hip fracture (94 individuals) during the study period, only the index fracture was included and they were censored at the time of the recurrent fracture. Secondary fractures due to a specific pathological lesion (e.g., malignancy) or high-energy trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights) were excluded.

Criteria for Myocardial Infarction and Death

The determination of postoperative myocardial ischemia occurring within the first seven days of surgery was ascertained in a two-phase process. First, patients who met the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (UDMI)20 criteria for postoperative MI were identified. The UDMI requires trending levels of cardiac biomarkers with at least one above the value of the 99th percentile for local laboratory upper limits of normal, in conjunction with ischemic changes in the electrocardiogram, clinical symptoms or imaging changes consistent with myocardial injury. In the second phase of MI identification, the clinical documentation of the first seven days following hip fracture repair from the respective hospitalization was reviewed in detail. These MI cases were then divided into two groups: 1) clinically verified MIs; and 2) subclinical myocardial ischemia. Patients with subclinical myocardial ischemia (sc-MI) were those who met the UDMI criteria, but their treating medical physician specifically excluded the MI diagnosis. Clinically verified MIs (cv-MI) were those who met UDMI criteria and were diagnosed with MI in the clinical record. Two cases were identified where a clinical diagnosis of MI was neither made nor excluded; rather the significant CK-MB elevations and patient symptoms were not addressed in clinical documentation. These cases were included in the cv-MI group. Deaths were identified either through the clinical record or the National Death Index.

Statistical methods

The data represent all consenting patients who underwent surgical repair of a hip fracture from Olmsted County between January 1, 1988 and December 31, 2002. No statistical sampling was performed. Data were abstracted through extensive review of the inpatient and outpatient medical records, including past medical diagnoses, index hospitalization laboratory and test data, patient symptoms and complaints during the hospitalization, demographic information and data regarding pre-fracture living and functional status. Data were recorded on paper forms by trained research nurses and entered into a SAS data set (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) by data entry specialists.

At the end of the first seven days following hip fracture repair, patients were classified into one of three groups: clinically verified MIs (cv-MI), subclinical myocardial ischemia (sc-MI) and no myocardial ischemia. Utilizing the UDMI for case definition, the rates of postoperative cv-MI and sc-MI in the first seven days following hip fracture repair were determined using the number of each respective cases as the numerator and all incident episodes of hip fracture repair in the study period as the denominator. Descriptive analyses were performed for the total population and for each of the three groups. Comparisons were analyzed with a proportional odds model. Frequency of occurrence of both cv-MI and sc-MI was calculated by day of hospitalization. One-year mortality was assessed for each of the three groups and compared using a Cox proportional hazards model. There was no statistical difference in the 1-year mortality rate between sc-MI and those patients who did not have a MI. Therefore, for all further analyses, the patients with sc-MIs were included in the no MI group.

To assess risk of early postoperative cv-MI, logistic regression analyses were performed including all of the variables in Table 1. Those variables with p-values less than or equal to 0.1 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model assessing risk of cv-MI within 7 days of surgical hip fracture repair. To assess risk of one-year mortality following surgical repair of hip fracture, a Cox proportional hazards model was performed including all variables in Table 1. Those variables with p-values less than or equal to 0.1 were included in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, past medical history and admission laboratory values for Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents who underwent hip fracture repair in 1988–2002

| No MI (N=942) | Clinically Verified MI (N=116) | Subclinical Myocardial Ischemia (N=41) | Total*(N=1099) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery (Mean (SD))Δ | 83.9 (7.5) | 85.0 (7.4) | 86.0 (6.5) | 84.1 (7.4) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 764 (81.1%) | 87 (75.0%) | 31 (75.6%) | 882 (80.3%) |

| Male | 178 (18.9%) | 29 (25.0%) | 10 (24.4%) | 217 (19.7%) |

| Race | ||||

| Other | 6 (0.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (0.7%) |

| White - Caucasian | 936 (99.4%) | 114 (98.3%) | 41 (100.0%) | 1091 (99.3%) |

| Past Medical History | ||||

| Myocardial infarctionΔ | 182 (19.3%) | 52 (44.8%) | 20 (48.8%) | 254 (23.1%) |

| Heart failureΔ | 227 (24.1%) | 49 (42.2%) | 14 (34.1%) | 290 (26.4%) |

| Cerebrovascular accidentΔ | 241 (25.6%) | 47 (40.5%) | 14 (34.1%) | 302 (27.5%) |

| Chronic kidney diseaseΔ | 89 (9.4%) | 21 (18.1%) | 11 (26.8%) | 121 (11.0%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 111 (11.8%) | 13 (11.2%) | 8 (19.5%) | 132 (12.0%) |

| Dementia | 309 (32.8%) | 46 (39.7%) | 16 (39.0%) | 371 (33.8%) |

| Preadmission functional status | ||||

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Dependent or use a wheelchair independently | 101 (10.7%) | 14 (12.1%) | 5 (12.2%) | 120 (10.9%) |

| Walk independently | 839 (89.3%) | 102 (87.9%) | 36 (87.8%) | 977 (89.1%) |

| Preadmission residence | ||||

| Facility (including assisted living) | 347 (36.8%) | 45 (38.8%) | 17 (41.5%) | 409 (37.2%) |

| Home | 595 (63.2%) | 71 (61.2%) | 24 (58.5%) | 690 (62.8%) |

| BMI | ||||

| Missing | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.3 (4.8) | 22.9 (5.3) | 23.8 (5.0) | 23.3 (4.9) |

| Length of hospital stay (Mean (SD)) | 9.9 (7.8) | 12.0 (8.4) | 9.6 (5.0) | 10.2 (7.8) |

| Preoperative laboratory results | ||||

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| Missing | 9 | 6 | 1 | 16 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.2 (1.6) | 12.0 (1.4) | 12.2 (1.2) | 12.2 (1.5) |

| Albumin | ||||

| Missing | 681 | 77 | 32 | 790 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.9) | 2.8 (1.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.2 (3.6) |

| Glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) Δ | ||||

| Missing | 113 | 34 | 7 | 154 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.8 (17.6) | 52.8 (20.0) | 47.6 (16.8) | 55.2 (17.8) |

| Postoperative CK-MB and Troponin I | ||||

| CK-MB | ||||

| Number of patients with values | 5 | 107 | 39 | 151 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.6 (0.7) | 25.5 (26.9) | 10.1 (4.4) | 20.9 (23.8) |

| Median | 6.9 | 17.0 | 10.4 | 13.9 |

| Troponin I | ||||

| Number of patients with values | 1 | 36 | 11 | 48 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.0) | 2.7 (6.5) | 0.2 (0.3) | 2.1 (5.7) |

| Median | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

All data is noted as N (%), unless otherwise indicated as mean, SD

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index

Chronic kidney disease is defined as creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl or requiring ongoing dialysis prior to hip fracture

17 patients died in close proximity to surgery without known diagnosis of MI, but were thought to possibly have had a cardiac event. These were excluded from the analysis given lack of objective information to appropriately classify them.

p < 0.05,

p<0.0001

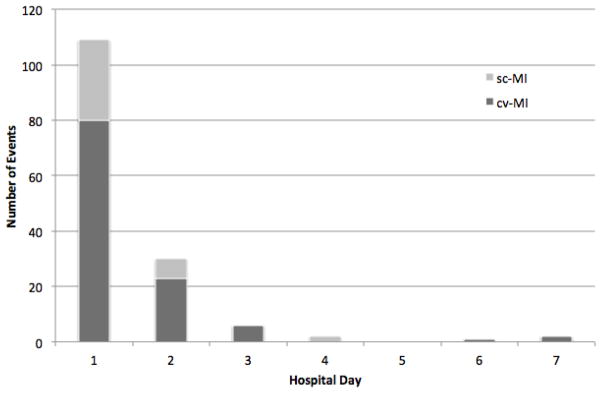

A landmark survival curve was generated using a set point of 7 days post-hip fracture repair. This seven-day landmark was selected since patients are still in the hospital, and therefore under the direct observation of surgeons and medical providers. Patients who were alive on day 7 were separated into two groups: (1) those that experienced an early cv-MI during the first 7 days following hip fracture repair, and (2) those that either did not have acv-MIin this time period. An unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed to estimate one-year survival for each group. An adjusted Kaplan-Meier analysis was also performed including all variables that were statistically significant (p < 0.05) for risk of 1-year mortality.

RESULTS

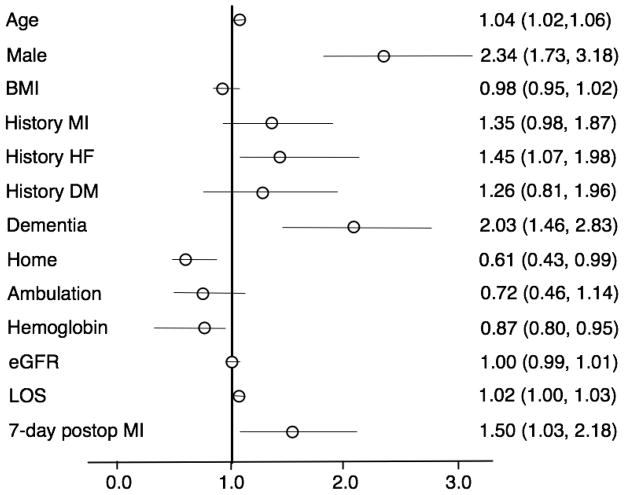

Of the 1,325 hip fractures that were diagnosed in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, 15.75% of them were excluded for the following reasons: nonsurgical treatment of fracture (56), pathologic fracture (20), surgical repair more than 72 hours following fracture (5), age less than 65 (3), multiple injuries (19), admission for other conditions (3), incomplete data (9) and recurrent fractures (94). All patients had previously provided consent for medical record review. Baseline characteristics of the remaining 1,116 patients who underwent surgical repair of hip fractures are detailed in Table 1. There were 157 (14.1%) patients who met the UDMI criteria for postoperative MI. Of these, 116 were clinically verified as MIs by the patient’s treating medical physician. The remaining 41 were considered, in the clinical record, to be consistent with subclinical myocardial ischemia and not reflective of true myocardial necrosis. The rate of cv-MIs during the first seven days following surgical repair of a hip fracture was 10.4%. Figure 1 depicts the occurrence of cv-MI and sc-MI by day of hospitalization through the first seven days.

Figure 1.

Frequency of unique patients with clinically verified MIs and enzymatic leaks by day of hospitalization.

The overall 1-year mortality rate for these study patients was 22.0%. The 1-year mortality rates for those with no MI, sc-MI and cv-MI were 20.2%, 27.5% and 35.8%, respectively. Cox proportional hazards model revealed the following hazard ratios (HR): 1.4 (95% CI 0.76–2.57) for those with sc-MI and 2.07 (95% CI 1.46–2.93) for those with cv-MI compared with those with no MI.

The peak CK-MB/troponin levels for those with no MI, sc-MI and cv-MI are reported in Table 1. Of those with cv-MI, eight were ST segment elevation MIs. Only one patient in the cv-MI group underwent cardiac catheterization and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. None of the cv-MI patients received thrombolytic therapy.

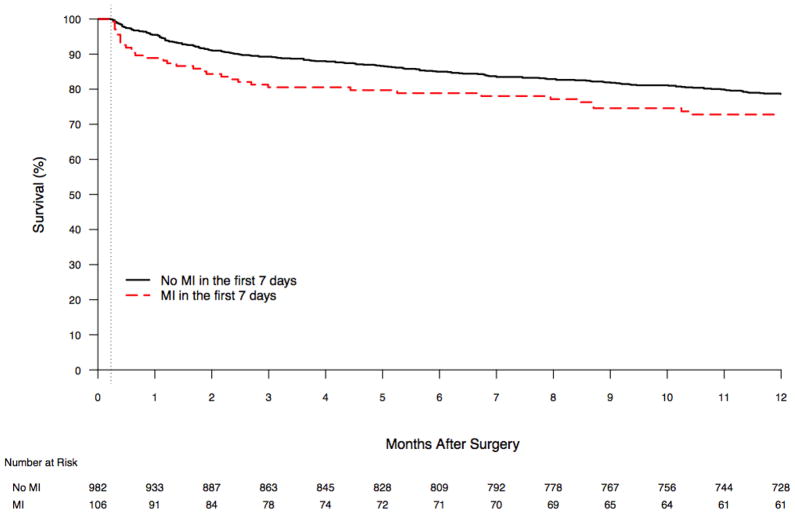

Results for the multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis performed to identify risk factors for one-year mortality are illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 3 depicts the adjusted landmark Kaplan Meier survival curve for those with and without a cv-MI in the first 7 days following surgery.

Figure 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard ratios of one-year mortality. BMI: body mass index; MI: myocardial infarction; HF: heart failure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LOS: length of hospital stay

Figure 3.

Adjusted seven-day landmark Kaplan Meier one-year survival curve adjusted

DISCUSSION

The rate of early postoperative MI within the first seven days of surgery was 10.4%. This is higher than rates reported in other studies.9,24 While we have captured the incidence in a geographically defined region, over 95% of all Olmsted County hip fractures are ultimately managed at one location; St. Marys Hospital, an academic facility. Resource utilization is known to be higher in academic settings compared to other hospitals.25 An MI diagnosis may have been made more often because specialists were more readily available or because laboratory studies were ordered more frequently. The definition of postoperative MI in this study was based on the UDMI guideline, determined primarily on biomarker results with supporting clinical information including electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, or catheterization results, or coronary artery bypass surgical requirement. An objective laboratory and test-based approach for diagnosis of postoperative MI is necessary because of the masking effects of anesthesia and postoperative narcotics for the more traditional clinical signs and symptoms in this postsurgical population, and for this study as the definition of MI is essential to the calculation if the disease incidence.

Local perioperative myocardial surveillance practices may influence postoperative MI study outcomes. Utilizing administrative data Lawrence et al. reported a much lower rate of “serious cardiac complication” of 2% during the hospitalization24. In order to have an MI diagnosed in the Lawrence et al. study, a patient had to first complain of chest pain. This results in an underestimation of MIs since the use of postoperative narcotics, presence of postoperative delirium, and other comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus) can mask the classic ischemic symptoms, creating an atypical presentation of ischemia. In another study, using clinical diagnosis only, physicians recognized only one-third of patients with myocardial injury following hip fracture repair.26 Our study was not limited to identifying patients with symptoms often masked in the immediate postoperative period or by clinician recognition. This may still be an underestimate, however, since routine myocardial surveillance for postoperative ischemia is not used in either hospital system.

The lack of a routine postoperative myocardial surveillance policy increases risk of measurement bias with any change in physician ordering patterns. We performed a secondary analysis to determine if there was a change in the rate of ordering cardiac biomarkers following hip fracture repair over time. From the beginning to end of the study period, there was an increase in the proportion of patients with at least one cardiac biomarker laboratory test completed in the first seven days following surgery (range from 4.4% in 1988 to 32.9% in 2002, p<0.0001). However, when evaluating proportion of patients with an early cv-MI, there was no change from year to year (p = 0.18).

Additional reasons for the possible differences in reported rates of postoperative MI may be attributable to referral bias and differences in ascertainment of follow-up. Patients in the Lawrence study were selected from 20 participating hospitals in 4 states. It is unknown if the surviving hip fracture patients in previously published studies of cardiac events post-hip fracture repair developed an MI and were treated in a non-study hospital. By limiting our study population to a geographically defined region, where the residents receive 99% of all care longitudinally, we are able to eliminate referral bias and can be confident in the completeness of our ascertainment of postoperative complications (100% one-year follow-up).

Research design will also influence study outcomes and could possibly explain the difference in postoperative MI in our series when compared to the published literature. In a study performed in the United Kingdom by Roche et al., the postoperative MI complication rate in post-hip fracture repair patients was 1%, but the details of how MI was defined was not included in the paper.9 Ho et al. investigated factors determining the one-year survival following hip fracture.27 Their research design utilized only administrative data sources to identify postoperative medical conditions and did not evaluate the clinical record for complications. In their cohort of 409 patients, only one was reported to have had a postoperative MI and this case was subsequently removed from their analysis.

While using the UDMI and cardiac biomarker levels as a trigger to investigate the medical record for evidence of MI may have lead us to over estimate the actual incidence of clinically significant ischemia, this is consistent with consensus agreement and current practice. Other studies have evaluated elevated troponin levels measured in the first few days after surgery and their prognostic significance.16–18 In a study reported by Dawson-Bowling, no patient with a normal troponin level postoperatively developed an MI.16 The diagnosis of MI in our study required a clinical presentation and findings in agreement with the UDMI with its detailing of significant changes of cardiac biomarkers, ECG, cardiac imaging, or resultant coronary artery catheterization or surgical bypass. The lack of difference in one-year mortality in our study between those with no myocardial ischemia and those who experienced anbiomarker leak may be related to the relatively small sample size of those with biomarker leaks. Others have identified worse outcomes in this group.16

In non-operative settings, outcomes following MI differ by age and gender.28, 29 We were unable to find any studies evaluating differences in rates of postoperative MI outcomes in hip fracture patients by gender or age. Our study did not identify any such differences in rates between gender or age groups, nor were there any significant by surgical year, suggesting that changes in surgical technique or perioperative medical management did not alter the risk of postoperative MI.

Several studies document the high degree of mortality in the hip fracture population.4, 27, 30–32 Boereboom previously described the early mortality rate in the first 8 weeks following surgery as being related to the hip fracture.4 Katelaris and Vestergaard also attribute the early and excess mortality to complications of the fracture event itself.26,30 One Olmsted County study of hip fracture patients occurring between January 1, 1989 and December 31, 1993 suggested most mortality occurred within 3 months of surgery.31 In a large Medicare Beneficiary Survey study of more than 25,000 hip fracture patients, Tosteson described postoperative mortality in these patients to be limited to the first 6 months, after adjusting for prefracture health status, functional impairments, and comorbid conditions.10 Another investigation reported that mortality in hip fracture patients greater than 85 years old returned to the level of age-matched general population 2–5 years after the fracture; while the mortality in those less than 85 years of age persisted for several years beyond.33 In our study, postoperative MI in the first seven days following surgery was associated with a decrease in one-year survival after controlling for other statistically significant covariates. Most of this survival difference occurred in the first month following surgery. This suggests that previously published trends in early mortality are at least partially explained by myocardial infarctions occurring in the early postoperative period. We did not investigate cause of death. Further study is needed to determine if this increased mortality is a marker for a sicker group of patients or directly related to the myocardial injury.

Population-based epidemiology data on cardiac complications following hip fracture repair has not been frequently reported. As a result, clinicians may be tempted to generalize rates of cardiac complications from similar procedures. The ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guideline classifies orthopedic surgery as an intermediate risk procedure. Therefore, it is assumed that all orthopedic patients will likely have less than a 5% risk of MI or mortality in the year following surgery. For standard elective procedures, this indeed may be so. Published rates of MIs reported from our institution’s Total Joint Registry were 0.4% following elective total hip or knee arthroplasty.7 However, the results from this hip fracture study strongly suggest that the current ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guideline is not applicable for this population of hip fracture patients.

This research has several limitations and is subject to biases inherent in retrospective cohort studies. Identifying hip fracture surgeries performed in all Olmsted County hospitals in Rochester, Minnesota minimized sampling bias. In addition, 100% one-year follow-up was possible with the ability of reviewing all inpatient, outpatient and nursing home records for all respective health care facilities in Rochester, Minnesota. Finally, including only incident cases of both surgical repair of hip fractures and postoperative MI minimized sampling bias. We minimized measurement bias by utilizing objective criteria for defining outcomes and verifying these laboratory findings with clinical assessments in the medical record.

The major weakness of this study is the age of the database used for analysis. There was no significant change in the incidence of postoperative MIs through the 15-year period of the study, indicating that any changes in surgical technique and perioperative medical management did not have a significant influence on this postoperative outcome during the period of the study. However, beyond the end of the study it is difficult to anticipate the impact that changes in perioperative medical care may have on these postoperative MI outcomes. There may have been changes in test ordering frequency or interventions for clinical scenarios concerning for possible or confirmed myocardial ischemia. The lack of data in this regard makes it difficult to translate data from this study to modern care scenarios.

The research population is more than 95% Caucasian and from a single community, bringing into question generalizability. Although prior studies have documented that matched hip fracture incidence rates in Olmsted County are similar to those for U.S. whites generally, and the socio-demographics of the general population of Olmsted County are similar to U.S. whites, our results should be replicated in other populations.8, 21

We chose a rather unorthodox postoperative outcome of a seven-day time period because during these early days following surgery, patients are usually still under the direct care of their surgeons and inpatient medical physicians. Understanding this window of time more thoroughly may provide an opportunity for providers to influence outcomes. In addition, this information is very relevant clinically when providing patients and their families with all of the necessary information regarding the risks and benefits of undergoing surgical intervention. MI following hip fracture repair most commonly occurs during the first week after surgery and may explain some of the excess mortality seen in these patients. The ACC/AHA preoperative cardiac evaluation guideline for major orthopedic surgery underestimates the incidence of MI following hip fracture repair. Further study is needed to deduce which factors, if modified, would increase patient survival by decreasing the ischemic burden in the perioperative period.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of patient-specific risk factors for early postoperative myocardial infarction following hip fracture repair

| Odds Ratio estimate | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Surgery | 1.03 | 0.99 – 1.06 |

| Male | 0.99 | 0.59 – 1.65 |

| Past Medical History | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 3.03 | 1.90 – 4.83 |

| Heart failure | 0.92 | 0.57 – 1.50 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.48 | 0.97 – 2.28 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.82 | 0.44 – 1.53 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) | 1.00 | 0.98 – 1.01 |

The odds ratio for eGFR is reported as a per 1 unit increment (ml/min/m2)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sherine Gabriel for her guidance and mentorship, and Donna K. Lawson, Kathleen Wolfert, and Cherie Dolliver for their assistance in data collection.

Funding for this study was made possible by AHA Grant #03-30103N-04, the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant # R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases) and by Grant Number 1 KL2 RR024151 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Jeanne M. Huddleston, MD – Primary investigator whose primary roles were study concept development, study design, acquisition of study subjects, data abstraction, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Rachel E. Gullerud – Data analyst whose primary roles included statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

FantleySmither – Co-investigator whose roles included interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript.

Paul M. Huddleston, MD – Principle orthopedic surgeon whose primary roles included study concept development and design, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript

Dirk R. Larson, MS – Lead statistician whose primary roles included study design, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

Michael P. Phy, DO – Co-investigator whose primary roles included study concept development, study design and preparation of the manuscript.

L. Joseph Melton, III, MD – Mentor whose primary roles included study concept development, study design, interpretation of data and manuscript editing and revisions.

Veronique L. Roger, MD – Senior investigator and mentor whose primary roles included study concept development, study design, interpretation of data and manuscript editing and revisions. All authors approved the final version submitted.

References

- 1.Popovic JR, Hall MJ Health NCf, Statistics. Advance data from vital and health statistics. Hyattsville; Maryland: 2001. 1999 National Hospital Discharge Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton LJ, 3rd, Kearns AE, Atkinson EJ, et al. Secular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrence. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:687–694. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0742-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsis JA, Phy MP, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Effects of a Hospitalist Care Model on Mortality of Elderly Patients with Hip Fractures. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):219–225. doi: 10.1002/jhm.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:796–801. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boereboom FT, Raymakers JA, Duursma SA. Mortality and causes of death after hip fractures in The Netherlands. Neth J Med. 1992;41:4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eiskjaer S, Ostgård SE. Risk factors influencing mortality after bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the treatment of fracture of the femoral neck. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantilla CB, Horlocker TT, Schroeder DR, et al. Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1140–1146. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melton LJ, 3rd, Therneau TM, Larson DR. Long-term trends in hip fracture prevalence: The influence of hip fracture incidence and survival. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:68–74. doi: 10.1007/s001980050050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, et al. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:1374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38643.663843.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosteson AN, Gottlieb DJ, Radley DC, et al. Excess mortality following hip fracture: The role of underlying health status. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1463–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0429-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poór G, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, et al. Determinants of reduced survival following hip fractures in men. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995:260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceder L, Elmqvist D, Svensson SE. Cardiovascular and neurological function in elderly patients sustaining a fracture of the neck of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63B:560–566. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B4.7298685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nettleman MD, Alsip J, Schrader M, et al. Predictors of mortality after acute hip fracture. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:765–767. doi: 10.1007/BF02598997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosencher N, Vielpeau C, Emmerich J, et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality after hip fracture surgery: The ESCORTE study. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2006–2014. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergqvist D, Fredin H. Pulmonary embolism and mortality in patients with fractured hips—a prospective consecutive series. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson-Bowling S, Chettiar K, Cottam H, et al. Troponin T as a predictive marker of morbidity in patients with fractured neck of femur. Injury. 2008;39:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher AA, Southcott EN, Goh SL, et al. Elevated serum cardiac troponin I in older patients with hip fracture: Incidence and prognostic significance. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ausset S, Minville V, Marquis C, et al. Postoperative myocardial damages after hip fracture repair are frequent and associated with a poor cardiac outcome: A three-hospital study. Age Ageing. 2009;38:473–476. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:e418–499. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2173–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullen MW, Gullerud RE, Larson DR, et al. Impact of heart failure on hip fracture outcomes: A population-based study. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:507–512. doi: 10.1002/jhm.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence VA, Hilsenbeck SG, Noveck H, et al. Medical complications and outcomes after hip fracture repair. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2053–2057. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mechanic R, Coleman K, Dobson A. Teaching hospital costs: Implications for academic missions in a competitive market. JAMA. 1998;280:1015–1019. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katelaris AG, Cumming RG. Health status before and mortality after hip fracture. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:557–560. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho CA, Li CY, Hsieh KS, et al. Factors determining the 1-year survival after operated hip fracture: A hospital-based analysis. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00776-009-1425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, et al. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker RC, Terrin M, Ross R, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes for women and men after acute myocardial infarction. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:638–645. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-8-199404150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture-effect of pre-morbid conditions and post-fracture complications. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1583–1593. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leibson CL, Tosteson AN, Gabriel SE, et al. Mortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: A population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1644–1650. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polsky D, Jha AK, Lave J, et al. Short- and long-term mortality after an acute illness for elderly whites and blacks. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1388–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston AT, Barnsdale L, Smith R, et al. Change in long-term mortality associated with fractures of the hip: Evidence from the scottish hip fracture audit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:989–993. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B7.23793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]