Abstract

Body dissatisfaction in women in the United States is common. We explored how women from various racial and ethnic groups used figural stimuli by exploring differences in current and preferred silhouette, and their discrepancy. We surveyed 4,023 women ages 25-45 in an on-line investigation. Participants were identified using a national quota-sampling procedure. Asian women chose a smaller silhouette to represent their current body size, which did not remain significant after adjusting for self-reported BMI. After controlling for BMI, African American women selected a smaller silhouette than White women to represent their current size. Both African American and women reporting “Other” race preferred larger silhouettes than White women even after controlling for BMI. The discrepancy score revealed lower body dissatisfaction among African American than White women. Understanding factors that promote body satisfaction differentially across racial and ethnic groups could become a tool in appropriately tailored interventions designed to prevent eating disorders.

Keywords: body image, figural stimuli, body mass index, race, ethnicity

Body dissatisfaction in women in the United States is ubiquitous and has been referred to as normative discontent (Millstein, Carlson, Fulton, Galuska, Zhang, Blanck et al., 2008; Rodin, Silberstein, & Striegel-Moore, 1985). The measurement of the concepts of body image and body satisfaction in women is complex and has often failed to consider important cultural factors such as race and ethnicity.

Body satisfaction and ethnicity

Few studies conducted with adults (Arugete, Debord, Yates, & Edman, 2005; Harris, 1994; Miller, Gleaves, Hirsch, Green, Snow & Corbett, 2000) have reported differences in body satisfaction across ethnic groups revealing the importance of incorporating culture and race in the evaluation of body image. When evaluating findings, important elements such as temporal trends, method of assessment, age of sample, and publication bias should be taken into consideration (Roberts, Cash, Feingold, & Johnson, 2006). Two intriguing patterns were reported by Cash, Morrow, Hrabosky, and Perry (2004). They conducted a cross sectional examination of multiple facets of body image over a 19 year period in both male and female college students. Significant changes in body image emerged over this observation period, especially in women. Non-Black women reported increasingly negative evaluations of their appearance and more weight preoccupation from the 1980s to the early and mid 1990s. In contrast, Black women did not report any changes in body image over this interval, but a decline in weight satisfaction was observed from the early to mid 1990s. Opposite results emerged between 1993 and 2001. During this period, ratings from both Black and non-Black women showed an improvement in the overall body satisfaction and fewer weight concerns.

A meta-analysis by Grabe and Hyde (2006) examined 98 studies of body dissatisfaction across ethnic and racial groups published between 1960 thru 2004. Consistent with previous literature (i.e., Roberts et al., 2006), Grabe and Hyde (2006) reported that White women reported greater body dissatisfaction than Black women. Hispanic women also reported greater body dissatisfaction than Black women. The differences were largest during adolescence and young adulthood. No differences were found in the comparison between White and Asian-American, White and Hispanic, Black and Asian-American and Asian-American and Hispanic women.

Other aspects of the body image such as skin color, facial features and hair texture are also relevant to of the appraisal of body satisfaction in some ethnic groups (Roberts et al., 2006). Developing easy-to-administer measures to capture the complexity of body dissatisfaction is challenging, and various approaches have strengths and limitations.

Measurement of body dissatisfaction

One widely used approach to assess body dissatisfaction, the use of figural stimuli, was introduced by (Stunkard, Sorensen, & Schulsinger, 1983). The approach requires the respondent to select which silhouette is closest to how they currently perceive themselves and which silhouette they would prefer to look like. From these two responses, three variables are derived current silhouette, preferred silhouette, and a silhouette discrepancy score (current-preferred), which has been interpreted as a measure of body dissatisfaction (Bulik Wade, Heath, Martin, Stunkard & Eaves, 2001).

Application of Silhouettes for Research Purposes

The silhouette-based approach has been widely used in epidemiologic investigations as an adjunct measurement to self-reported height and weight and as an independent and simple-to-administer measure of body satisfaction. Although criticisms of the instrument include cultural insensitivity [because the silhouettes have not been appropriately culturally adapted to reflect differences of body shape and composition across ethnic groups (Patt, Lane, Finney, Yanek, & Becker, 2002)], limited response options, and being a rather coarse measure, more sophisticated methods of body size estimation have little evidence of significantly greater reliability or validity and are often impractical in large epidemiologic studies (Bulik et al., 2001). Other concerns raised by Gardner and colleagues (Gardner, 2001; Gardner, Friedman, & Jackson, 1998) include the fact that the presentation method is likely to produce spuriously high test-retest reliability coefficients, because respondents can readily recall which figure they selected initially and the figural scale focuses on the whole body and is unable to capture nuances in body dissatisfaction (e.g., satisfied with waist but dissatisfied with thighs). Although, alternate versions of figural stimuli have been tested for their utility across racial and ethnic boundaries and to adapt to the increasing body size in the U.S. population (Patt et al., 2002), clear use guidelines do not yet exist. Sex-specific BMI norms for the silhouettes in Caucasian populations have been established by Bulik et al. (2001) to enrich the yield of the figural stimuli research.

The goals of this study were to explore several aspects of the figural stimuli methodology across racial and ethnic groups. Specifically, we: (1) determined the extent to which women across racial and ethnic groups used the stimuli in a similar manner; (2) explored racial and ethnic differences in current, preferred silhouette as well as in the discrepancy measure; and (3) determined the extent to which any observed differences were due to BMI.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The study sample comprised 4,023 female U.S. residents, ages 25-45, with computer access, who consented to participate in an online “eating habits” survey. The study was a cooperative effort between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Self magazine (Reba-Harrelson, Von Holle, Hamer, Swann, Reyes, & Bulik, in press). Neither UNC nor Self magazine was identified in any way with the survey. Participants completed the online survey in exchange for the incentive of being entered into a drawing with a monetary prize. The survey included many questions about eating and dieting as well as a figural stimuli question taken from a previously fielded questionnaire (Bulik, Tozzi, Anderson, Mazzeo, Aggen, & Sullivan, 2003; Neale, Mazzeo, & Bulik, 2003; Slof, Mazzeo, & Bulik, 2003).

The Equation Research Company organized the survey in which 100,000 people in a marketing research online survey panel were sent email invitations to participate. Quota sampling in the context of this study refers to a sampling method in which the first of a predetermined number of participants are selected, the number being 4,000 for this survey. After the number of participants exceeded approximately 4,000, the survey was terminated. The quota sampling strategy stratified on four age groups: 25-29, 30-34, 35-39 and 40-45 to match 2006 U.S. Census data (http://www.census.gov/acs/www/). Following completion of the sample, post-stratification weights were created for age, race, and ethnicity. Post-stratification weights ensure that the proportions for age, ethnicity, and race in the sample match that of the U.S. Census proportions.

An invitation email was sent and dissemination was completed once the quota sample of 4,023 women who consented to participate in the current study completed their questionnaires. In total, 4,686 women responded to the survey. Two-hundred and eighty-six were excluded due to failure to complete the questionnaire, 94 were excluded due to not answering the screening question to establish eligibility (e.g., age within the targeted age band), and 283 were terminated once the pre-determined quota was reached. The invitation email contained a link to the survey and an online consent form. Participants completed the survey confidentially. UNC researchers were not able to access any identifying information provided by participants. De-identified data were sent to UNC, where all data analysis was performed. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UNC Chapel Hill.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Participants self-reported their racial and ethnic identity. We followed current race and ethnicity classifications used by the National Institutes of Health. Race response options included: (1) White, (2) Black or African-American (AA), (3) Asian, (4) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (NH/PI), (5) American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/NA), or (6) Other. Only one selection was allowed for the question regarding race. Ethnicity was defined as Spanish, Hispanic, or Latina group membership (e.g., all participants were classified as either Hispanic or non-Hispanic). Further delineation within the ethnicity groups divided the non-Hispanic group into ‘White’ and ‘non-White’. This division was not possible for those indicating Hispanic ethnicity because of small sample size for the non-white Hispanic group. Other demographic variables measured were age, education level, socioeconomic status, partner status, height, and weight.

Current Silhouette and Preferred Silhouette

The figural stimuli we used are shown in the Appendix. Each woman was asked the following questions: ‘Which silhouette is closest to what you currently look like?’ and ‘Which silhouette would you prefer to look like?’ (see Appendix). Participants were to select one of the nine silhouettes used in a previously fielded questionnaire (Bulik et al., 2003; Neale et al., 2003; Slof et al., 2003) in response to each of the above questions. Silhouettes were given a value of 1 to 9 with 1 being the smallest value and 9 being the largest. Participants did not see the numbers and were asked to choose based on the visual cues of the silhouette only.

Statistical Analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative statistics were used in this descriptive study. We performed range and value checking for the main variables to examine missing data or implausible values. We examined percent distributions for preferred silhouette by racial and ethnic status. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3.

To determine the level of bias in the study quota sample we conducted two comparisons to alternate samples. First, we compared our dataset to the U.S. Census Data from 2006 for women ages 25-45, examining distributions of race and relevant demographic variables, such as education and income (U. S. Census, 2006). The main differences between the Self unweighted sample and the U.S. Census data include over-representation of whites and non-Hispanics, women with post-secondary education, and women in a lower income bracket in the Self unweighted sample. Once weighted, the racial and ethnic differences across the two surveys declined.

Secondly, we compared the Self data to the Virginia Twin Registry (VTR) dataset (Neale et al., 2003; Slof et al., 2003). Separate regressions were performed using VTR and Self data to compare the regression coefficients. After controlling for age at interview, there was less than 15% difference between regression coefficients indicating similarity between the two survey silhouette measures. This comparison is described in more detail in (Reba-Harrelson et al., in press).

Analyses included comparisons of the mean current silhouette and silhouette discrepancy scores by race and ethnicity using multivariable linear regressions. For each silhouette score the first model included race or ethnicity as a covariate and the post-stratification weight variable as another covariate in all models to control for non-response (Berinsky, 2006). The second model adjusted for BMI as a categorical variable according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cut points: underweight (< 18.5), normal weight (18.5 - 24.9), overweight (25.0 - 29.9), and obesity (≥ 30.0).

For the preferred silhouette response variable, we used a non-parametric analysis because it provided better model fit than a multivariable linear regression. We computed Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) row mean scores statistics to examine patterns in preferred silhouette scores across race and ethnicity. Each racial group was compared to the ‘White’ group using this approach with and without BMI as a control variable. A significant statistic signals a location shift in the distribution of the preferred silhouette score across the compared groups, either race or ethnicity.

Results

Demographics

Demographic characteristics for the sample have been previously described (Reba-Harrelson et al., in press). Four women were excluded from the 4,023 participants in the sample because of implausible height values. There were 4,019 participants yielding a weighted estimate of 4,015 women after applying the remaining post-stratification weights. This group reported a mean age of 35.19 (SD = 5.87) years and a mean BMI of 29.26 (SD = 8.36) kg/m2. The BMI distributions by race and ethnicity are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean BMI by Race and Ethnicity.

| Characteristics | N (%) | BMI (kg/m2) (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 3,007 (74.89) | 29.18 (8.34) |

| Black or African-American | 542 (13.49) | 31.30 (8.84) |

| Asian | 184 (4.59) | 23.76 (4.49) |

| American Indian, Alaska Native | 36 (0.90) | 31.17 (7.81) |

| Other | 238 (5.93) | 29.74 (7.91) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 8 (0.20) | 24.72 (4.53) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 536 (13.35) | 30.08 (8.41) |

| Non-White/non-Hispanic | 772 (19.24) | 29.24 (8.46) |

| White/non-Hispanic | 2,706 (67.41) | 29.10 (8.31) |

Current Silhouettes

Arithmetic mean current silhouette scores by race and ethnicity are presented in Table 2. We estimated the difference between the mean current silhouette chosen by racial and ethnic groups relative to the referent with linear regression models and then repeated the analysis controlling for self-reported BMI as also reported in Table 2. Asian women chose a significantly smaller current silhouette, −1.16 (p < .01) units less than the referent White women, although this was no longer significant after controlling for BMI. African American women chose a significantly smaller current silhouette, −0.26 units (p < .01), less than the referent when controlling for BMI. As noted previously in the methods, models with and without BMI as a control variable include the post-stratification weight as a covariate. No statistically significant differences emerged in current silhouette choice between Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups.

Table 2. Means and Comparisons of Current Silhouettes and Silhouette Discrepancy Mean Scores.

| Current Silhouette |

Silhouette Discrepancy |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression |

Regression |

|||||||||||||

| Not adjusted for BMIa | Adjustment for BMI | Not adjusted for BMIa | Adjustment for BMI | |||||||||||

| β | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | β | SE | p | |||

| Mean (SD) |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Mean (SD) |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

|||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||||||

| Black or African-American | 5.90 (1.72) | −0.01 | 0.14 | .95 | −0.26 | 0.09 | <.01 | 1.80 (1.19) | −0.31 | 0.10 | <.01 | −0.46 | 0.08 | <.01 |

| Asian | 4.80 (1.31) | −1.16 | 0.21 | <.01 | −0.01 | 0.13 | .95 | 1.40 (0.97) | −0.80 | 0.16 | <.01 | −0.11 | 0.12 | .53 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 4.50 (1.51) | na | na | na | na | na | na | 1.20 (1.03) | na | na | na | na | na | Na |

| American Indian, Alaska Native | 5.80 (1.44) | 0.16 | 0.28 | .76 | −0.08 | 0.18 | .76 | 2.10 (1.19) | 0.23 | 0.21 | .41 | 0.08 | 0.16 | .76 |

| Other (Please specify) | 6.00 (1.58) | −0.10 | 0.21 | .76 | −0.05 | 0.13 | .82 | 2.10 (1.22) | −0.26 | 0.15 | .16 | −0.17 | 0.12 | .24 |

| White | 5.70 (1.63) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2.00 (1.20) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ethnicity | Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 7 |

Model 8 |

||||||||||

| Hispanic | 5.90 (1.55) | 0.03 | 0.36 | .95 | −0.11 | 0.22 | .76 | 2.10 (1.17) | 0.07 | 0.26 | .88 | 0.03 | 0.20 | .94 |

| Non-White/non-Hispanic | 5.60 (1.67) | −0.17 | 0.20 | .60 | −0.22 | 0.13 | .16 | 1.70 (1.15) | −0.26 | 0.15 | .16 | −0.26 | 0.11 | .04 |

| White/non-Hispanic | 5.70 (1.64) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.90 (1.21) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Note. ‘na’ = ‘not applicable’ because this group had a sample size too small for regression analysis.

No other covariate in the model except the post-stratification weight value

Preferred Silhouettes

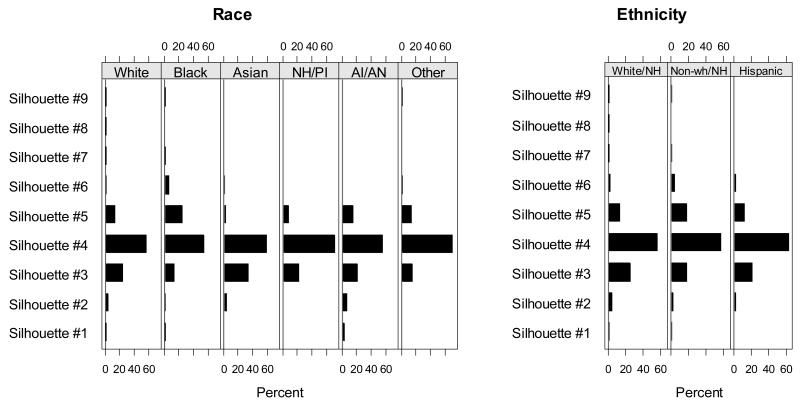

The distribution of preferred silhouette scores for women across racial and ethnic groups is presented in Figure 1. The distribution of preferred silhouette scores were compared across race and ethnicity first without and then with adjustments for self-reported BMI. First, in the uncontrolled model, proportionately more women in the African American group chose Silhouettes 5 -7 and women in the “Other” groups chose Silhouettes 4-5 relative to the White group. Before controlling for BMI, tests indicated significant location shifts in the distribution of preferred silhouettes for African Americans (CMH = 115.61, p < .01), the “Other” group (CMH = 19.98, p < .01), and Asians (CMH = 8.85, p < .01). For all racial groups, less than one percent of the population selected each of the preferred Silhouettes 7-9. In contrast, Asian women chose proportionately less of Silhouettes 5-7 than women in the White group. The significant differences in the distributions of preferred silhouettes for African American and “Other race” women persisted after controlling for BMI; however, the differences in the Asian women were no longer significant. No significant differences emerged in preferred silhouette between Hispanic groups.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of “preferred” silhouette by race and ethnicity

Discrepancy Scores (Current – Preferred Silhouettes)

For clarity, the silhouette discrepancy score was computed by taking the absolute value derived from subtracting the preferred silhouette from the current silhouette. Larger numbers indicate a greater discrepancy in the direction of current body size being more extreme than the preferred body size. This score is generally considered to be a measure of satisfaction with current body size. The mean discrepancy score of the referent group was 2.00 (SD = 1.20) (see Table 2). The higher the absolute value, the greater the discrepancy between current and desired size. Comparing across racial groups and not controlling for BMI, Asian women and African American women reported significantly smaller silhouette discrepancy scores, −0.31 (p < .01) and −0.80 (p < .01) units less than the referent, respectively (Table 2). Controlling for BMI this significant difference persisted only for African American women with a discrepancy score difference of −0.46 units (p < .01). Comparing across ethnic groups we found no statistically significant mean discrepancy scores between Hispanic women and the referent group, White/non-Hispanic.

Discussion

We compared the use of figural stimuli across women of differing racial and ethnic groups. Through the exploration of racial and ethnic differences in current and preferred silhouette as well as in the discrepancy measure, we were able to observe the manner in which the stimuli were used by women across racial and ethnic groups and evaluate differences in desired body size and satisfaction while accounting for the influence of BMI.

Our findings relative to current silhouette indicated that while Asian women chose a smaller silhouette to represent their current body size that selection appears to reflect the fact that they do tend to be smaller overall as indexed by their self-reported BMI. Women with similar self-reported BMI report similar current silhouettes across Asian and White ethnic groups. In contrast, even after controlling for BMI, African American women selected a smaller silhouette than White women to reflect their current size. This result shows that differences do exist in how the stimuli are interpreted across groups with African American women perceiving their body size as smaller than White women with equivalent BMIs. This corroborates previous findings with adolescent African American females who perceive themselves as thinner than similarly sized White adolescent females (Parnell, Sargent, Thompson, Duhe, Valois, & Kemper, 1996). We did not observe any differences by ethnicity.

Both African American and “Other” race women preferred larger silhouettes than the referent White group even after controlling for BMI. Both social and cultural norms are said to influence the acceptance of larger body size in African American females and greater thin-ideal internalization in White women (Becker, Yanek, Koffman, & Bronner, 1999; Parnell et al., 1996; Powell & Kahn, 1995).

Our measure of body satisfaction—the discrepancy score revealed lower body dissatisfaction among African American women. On this measure we did not detect statistically significant differences by ethnicity. Higher discrepancy scores may put women at risk for engaging in high risk weight control practices in order to control their weight or attain their ideal body size. Although previous research has focused on eating disorders as being concentrated largely within the White, non-Hispanic population, accumulating information suggests that eating disorders do not discriminate and that Hispanic women are also at risk for eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors (Alegria, Woo, Cao, Torres, Meng, & Striegel-Moore, 2007; Cachelin, Rebeck, Veisel, & Striegel-Moore, 2001; Franko, Becker, Thomas, & Herzog, 2007; Reba-Harrelson et al., in press).

Important elements have to be considered in the evaluation of the body image perception and satisfaction across race and ethnicity. Self-identification in a specific ethnic group and the internalization of the dominant culture contribute to the complexity of the manifestation of body satisfaction (Harris, 1994). Understanding the complexity of body image and satisfaction requires an appreciation of biological/genetic differences in body shape and size, any within-race and within-ethnicity normative concepts of body image, as well as how each of these elements interact with those of the dominant culture. More detailed qualitative research may further enrich our understanding of racial and ethnic differences in the perception of and satisfaction with body size and shape as a first step in developing culturally sensitive interventions for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating.

The limitations of this study must be considered. First, participants were volunteers who completed an online survey. The appropriateness of this approach was verified through comparisons with other population-based data. Although this remains a limitation, there are advantages to online sampling, including access to individuals in distant locations and the simplicity of data collection, saving both researcher time and economic resources (Kraut, Banaji, Bruckman, Cohen, & Couper, 2003; Wright, 2004). Second, as with all self-reported data there is potential for participants to over-report or under-report and impact the accuracy of response data. Of particular concern is the accuracy of self-reported height and weight. Adult woman tend to underestimate their weight and overestimate their height and the underestimation increases with age (Brunner Huber, 2007; Meyer, McPartlan, Sines, & Waller, 2009). Although objective measures are always preferred, especially when studying women with eating and body image concerns (Meyer et al., 2009), in large studies, and on-line studies such as these, such measures are impractical. Given that we observed some racial and ethnic differences, and given that our sample sizes for some ethnic groups were small, we must evaluate our results with caution (Brunner Huber, 2007). Larger studies validating self-report height and weight across racial and ethnic groups are required. Third, participants had to have internet access to complete the survey, which could skew the reflection of the general population. However, comparisons were made to the U.S. population data and our sample demonstrates accuracy in the majority of the demographic variables. Fourth, our definitions of race and ethnicity were imperfect. The appropriate classification of both race and ethnicity is a subject of much debate. Our adherence to a common yet imperfect classification approach adopted by the US government, although sound, did not enable us to explore more subtle differences across racial and ethnic groups. Moreover, we included a racial categorical variable of “Other” and these individuals we are simply unable to classify. Future studies may need to allow for more nuanced racial and ethnic categories to more accurately reflect the cultural diversity of the population. For example categories should reflect the reality of ethnic minority groups (e.g., Latinos) which is comprised of a variety of races. Fifth, we did not assess sexual orientation and are therefore unable to draw any conclusions about the impact of sexual orientation on body satisfaction. Sixth, since BMI norms for these silhouettes are only available on white women, we were not able to compare results of women from other races or ethnicities to external samples.

Bearing these limitations in mind, our results do illustrate differences across races in both body size preference and satisfaction. A more detailed and qualitative approach to understanding these differences could aid identifying protective and risk factors associated with body dissatisfaction. Future research on race/ethnicity and body dissatisfaction should include a comprehensive assessment of the acculturation process which considers the duration of living in United States, language of preference, and other cultural values. Our results could be brought to bear on the observation that anorexia nervosa has been shown to be less common in African American women (Striegel-Moore, Dohm, Kraemer, Taylor, Daniels, Crawford et al., 2003). It is plausible that the more favorable perception of one’s body size serves as a protective factor against engaging in unhealthy dieting and weight control practices that may lead to disordered eating or a frank eating disorder. Understanding factors that promote body satisfaction differentially across racial and ethnic groups could become a tool in appropriately tailored interventions designed to prevent eating disorders.

Appendix: Figural stimuli

References

- Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng XL, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(Suppl):S15, 21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arugete MS, Debord KA, Yates A, Edman J. Ethnic and gender differences in eating attitudes among black and white college students. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DM, Yanek LR, Koffman DM, Bronner YC. Body image preferences among urban African Americans and whites from low income communities. Ethnicity and Disease. 1999;9:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky A. American Public Opinion in the 1930s and 1940s - The analysis of quota-controlled sample survey data. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:499–529. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner Huber LR. Validity of self-reported height and weight in women of reproductive age. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2007;11:137–144. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Tozzi F, Anderson C, Mazzeo S, Aggen S, Sullivan PF. The relation between components of perfectionism and eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:366–368. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Wade TD, Heath AC, Martin NG, Stunkard AJ, Eaves LJ. Relating body mass index to figural stimuli: population-based normative data for Caucasians. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2001;25:1517–1524. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Rebeck R, Veisel C, Striegel-Moore RH. Barriers to treatment for eating disorders among ethnically diverse women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:269–278. doi: 10.1002/eat.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Morrow JA, Hrabosky JI, Perry AA. How has body image changed? A cross-sectional investigation of college women and men from 1983 to 2001. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1081–1089. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, Herzog DB. Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:156–164. doi: 10.1002/eat.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RM. Assessment of body image in children and adolescents. In: Thompson JK, Smolak L, editors. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RM, Friedman BN, Jackson NA. Methodological concerns when using silhouettes to measure body image. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1998;86:387–395. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.86.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabe S, Hyde JS. Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction among women in the United States: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:622–640. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SM. Racial differences in predictors of college women’s body image attitudes. Women’s Health. 1994;21:89–104. doi: 10.1300/J013v21n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Banaji M, Bruckman A, Cohen J, Couper M. Psychological research online: Opportunities and challenges. 2003. Retrieved November 7, 2009, from www.apa.org/science/apainternetresearch.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, McPartlan L, Sines J, Waller G. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height: relationship with eating psychopathology among young women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:379–381. doi: 10.1002/eat.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Gleaves DH, Hirsch TG, Green BA, Snow AC, Corbett CC. Comparisons of body image dimensions by race/ethnicity and gender in a university population. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:310–316. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<310::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstein RA, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Zhang J, Blanck HM, Ainsworth BE. Relationships between body size satisfaction and weight control practices among US adults. Medscape Journal of Medicine. 2008;10:119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale BM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM. A twin study of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination of the eating inventory (Three Factor Eating Questionnaire) Twin Research. 2003;6:471–478. doi: 10.1375/136905203322686455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell K, Sargent R, Thompson S, Duhe S, Valois R, Kemper R. Black and white adolescent females’ perceptions of ideal body size. Journal of School Health. 1996;66:112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patt M, Lane A, Finney C, Yanek L, Becker D. Body image assessment: comparison of figure rating scales among urban Black women. Ethnicity and Disease. 2002;12:54–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AD, Kahn AS. Racial differences in women’s desires to be thin. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;17:191–195. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199503)17:2<191::aid-eat2260170213>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reba-Harrelson L, Von Holle A, Hamer R, Swann R, Reyes M, Bulik C. Patterns and prevalence of disordered eating and weight control behaviors in women ages 25-45. Eating and Weight Disorders. doi: 10.1007/BF03325116. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Cash TF, Feingold A, Johnson BT. Are black-white differences in females’ body dissatisfaction decreasing? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1121–1131. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, Silberstein L, Striegel-Moore R. Women and weight: A normative discontent. In: Sonderegger T, editor. Psychology and gender: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 1985. pp. 267–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slof R, Mazzeo S, Bulik C. Characteristics of women with persistent thinness. Obesity Research. 2003;11:971–977. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore R, Dohm F, Kraemer H, Taylor C, Daniels S, Crawford P, Schreiber GB. Eating disorders in white and black women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1326–1331. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard A, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. In: Kety S, Roland L, Sidman R, Matthysse S, editors. The Genetics of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Raven Press; New York: 1983. pp. 115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census, B. American Community Survey. 2006. Retrieved November 6, 2009, from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/ [Google Scholar]

- Wright K. Making the most of online learning. Nursing Times. 2004;100:74–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]