Abstract

Background:

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) being more common in rural areas, the collection of serum may not always be possible or may be hazardous in untrained hands. The alternative, noninvasive samples like saliva and urine which are non invasive and easy to collect need to be evaluated for diagnosis of CE.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to evaluate hydatid antigen detection by ELISA in urine and saliva samples by comparing them with antigen detection in serum for diagnosis of CE.

Materials and Methods:

Serum, saliva and urine samples were collected from 25 clinically and radiologically diagnosed CE patients, 25 clinically suspected cases of CE, 15 other parasitic disease controls and 25 healthy controls. Hydatid antigen detection was done in these samples by Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay using hyperimmune serum raised in rabbits immunized with hydatid antigen.

Results and Conclusions:

The sensitivity of ELISA for antigen detection in serum, saliva and urine was found to be 40%, 24% and 52% respectively. Urine showed significantly higher (p<0.05) sensitivity than that of saliva samples but not significantly higher (p>0.05) than that of serum samples. The specificity was highest for serum (92.5%) followed by saliva (87.5%) and urine (80%). There was no significant difference in antigen detection in patients with single vs multiple cysts. There was no significant difference in antigen detection in patients with hepatic vs extrahepatic cysts in serum or saliva samples but antigen positivity in urine was significantly higher (p<0.05) in hepatic cysts than that in extrahepatic cysts. The results showed that biological fluids like urine and saliva may be used as an alternative or as an adjunct to serum samples by virtue of their noninvasive, easy collection and similar sensitivity and specificity.

KEYWORDS: Antigen, Echinococcosis, hydatid, immunodiagnosis, serodiagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Human echinococcosis is a cosmopolitan zoonosis caused by larval stage of the cestode parasite, Echinococcus granulosus.[1] The annual incidence of cystic echinococcosis (CE) in different parts of the world has been reported to vary from < 1 to 220 per 100,000 persons, in various endemic areas, with mortality rates ranging between 2 and 4%.[2] CE constitutes a significant disease burden in human and livestock in India and has been reported from all parts of the country.[3,4] Although the liver is the most frequently involved site, the cysts can develop in almost all organs of the body.[5]

The diagnosis mainly depends on radiological and immunological techniques, although recently molecular biology techniques have also been applied. Although demonstration of scolices, hooklets or protoscolices in aspirated fluid by microscopy is very specific, yet aspiration of hydatid fluid for diagnosis is not usually recommended, because of the risk of an anaphylactic reaction. Radiological techniques are too expensive and often the radiological picture may mimic other pathologies. Casoni's intradermal skin test is associated with low sensitivity and specificity.[6] Thus, routine laboratory diagnosis of CE is heavily reliant on serological tests.[5]

One of the main problems of hydatid specific antibody detection is that 25 – 40% of surgically confirmed patients fail to show antibodies, whatever may be the technique or antigen employed.[7–11] Moreover, the circulating antibodies persist in the circulation for a long time; even after removal of the cyst by surgery or a clinical cure by chemotherapy.[7] Therefore, the antibody-based serological tests fail to demonstrate whether the infection is recent or old, and are of limited value in monitoring the effect of the treatment or prognosis of the disease.[3]

The circulating hydatid antigen is present in an active or recent infection and is absent in patients treated with surgery or chemotherapy.[7,12] The detection of the circulating antigen may not only help in the diagnosis of an active infection, but also in the prognosis of the cases. Studies have indicated that the detection of the circulating antigen is useful in detecting hydatid disease in antibody-negative patients and also in assessing the status of the infection.[3,12]

The serum is generally used as a specimen for immunological tests. However, the collection of blood samples can be problematic, particularly in remote rural areas and being an invasive procedure may be hazardous and unsafe in untrained hands. Thus, it is important to assess alternative, simple, painless methods of sampling body fluids that give results as accurate as those obtained with blood samples. Saliva and urine have been suggested as possible alternatives and are increasingly being reported as non-invasive means to detect specific antibodies to diagnose various diseases.[13–15] Use of these samples confers clear advantages, such as, easy sample collection, which does not require expert personnel, does not cause trauma to the patients, and minimizes the risk of infection for health workers. There are only a few studies on the use of urine for hydatid antigen detection[12,16] and none on the use of saliva.

The present study reports the use of saliva and urine samples for hydatid antigen detection by ELISA and its comparison with the detection of antigen in the serum samples, for the diagnosis of CE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Fifty patients admitted to or attending the Outpatient Departments and diagnosed with hydatid disease either clinically and/or radiologically, were enrolled for the study. Detailed clinical history and radiological findings were recorded from all the patients. Fifteen patients with other parasitic diseases (five each of cysticercosis, ascariasis, and amebic liver abscess) were also included as other parasitic disease controls. Twenty-five normal healthy subjects who were found negative for intestinal helminthic infections by stool examination and negative for hydatid antibody were included as healthy controls. An informed written consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Samples

Blood, saliva, and urine samples were collected from all the patients and controls. Serum was separated from the blood samples and preserved at -20°C till further use. Unstimulated whole saliva samples were collected from individuals into wide mouthed containers. Immediately after collection, protease inhibitors, aprotinin (sigma), and pepstatin A (sigma) were added at a final concentration of 2 μg (each)/ml to the saliva.[17] Urine samples were collected in sterile containers, and stored at -20°C until further use.[18]

HYDATID ANTIGEN DETECTION

Preparation of rabbit hyperimmune antiserum against hydatid antigen

Two healthy, adult, male, white New Zealand rabbits, six to eight months of age, were used for raising antisera against the hydatid antigen. For the antigen preparation, hydatid cysts were obtained from freshly slaughtered and heavily infected sheep at the local abattoirs. The daughter cysts were taken from intact hydatid cysts dissected from sheep liver, were washed thrice, and suspended in normal saline. The suspension was homogenized thoroughly and sonicated five times (24 seconds each) at 20 KHz, for a total of two minutes, with 30-second intervals. The sonicated material was centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant, the hydatid cyst fluid antigen, was stored at -70°C in 1 ml aliquots, after determining the protein content by the Lowry's method. The rabbits were immunized with 1.5 ml of hydatid antigen, having a protein concentration of 8 mg/ml, with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant, subcutaneously, and then four such injections at one-week intervals, with Freund's incomplete adjuvant. The rabbits were bled from the ear vein, seven days after the last injection, and the serum was checked for the presence of anti-hydatid antibodies, by the gel diffusion test. As gel diffusion showed distinct bands of precipitation, the rabbits were bled from the heart to collect as much blood as possible without sacrificing the animal. The serum was separated, antibodies were purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation, and dialysis[19] and stored at -70°C.

Double sandwich ELISA for detection of hydatid antigen in serum samples

Double antibody sandwich (DS) ELISA for detection of antigen in serum was carried out according to the standard technique,[20] with certain modifications wherever required. The secondary antibody used in the test was purified human anti-hydatid IgG (pooled from five confirmed hydatid disease patients, showing a high titer of antibodies by ELISA). Optimum dilutions of hyperimmune serum to be coated on the wells of the microtiter plates, secondary antibody, and conjugate were predetermined by the checker board titration method, and were 2 μgm / well, 0.3 μgm / well, and 1 : 4500 dilution, respectively. Similarly optimum dilutions of serum, urine, and saliva samples were determined to be 1 : 100, 1 : 20, and 1 : 40, respectively. The DS ELISA was performed using the standard protocol.[21] Briefly, the wells of the ELISA plate were coated with 100 μl of the purified anti-hydatid antibody (diluted to 2 μg / 100 μl) and kept overnight at 4°C. After washing, the blocking of the unbound sites of the wells was done with 2% Bovine serum albumin (BSA). Test and control sera diluted in phosphate buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBST) was added (100 μl each), incubated at 37°C for one hour, and washed thrice with PBST. Next, 100 μl of the secondary antibody was added and incubated at 37°C for one hour. After washing with PBST, 100 μl of anti-human IgG-horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Dakopatts, Denmark) was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After washing, 100 μl of ortho phenylenediamine (OPD) was added to each well and kept at room temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction was stopped with 1M H2SO4, and the plates were read in an ELISA reader at 490 nm and the optical density (OD) was recorded. Five known negative controls were included in each batch of the test and the cut off OD was calculated by adding two standard deviations (SD) to the mean of five negative samples. The cut off OD was found to be 0.153 for the serum samples, 0.053 for the urine samples, and 0.056 for the saliva samples. Samples with OD values equal to or more than the cutoff OD value were considered as positive. For the calculation of sensitivity and specificity, the samples of 25 patients diagnosed as CE on the basis of surgical and radiological findings were taken as true positive, as no gold standard parameter was available for the diagnosis of human hydatidosis. The results were compared between patients and control groups and evaluated statistically by the student's paired’t’ test and Chi-square test.

The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

The Male : Female ratio in the 50 clinically diagnosed/suspected hydatid disease patients was 2.3 : 1 and the mean age was 41.3 years, while two were children. Out of these 50 patients, only 25 patients were clinically and radiologically diagnosed with hydatidosis, out of which four were also confirmed to be CE, after surgery. Eighteen of the clinically and radiologically diagnosed cases had hepatic cysts, while seven had extrahepatic cysts (four lung cysts, one each in the liver and lung, and one each in the kidney and ovary).

The Male : Female ratio in the 25 healthy controls was found to be 1 : 1.3, while the mean age was 38 years. The Male : Female ratio in the other parasitic disease controls was found to be 1.9 : 1, while the mean age was 40 years.

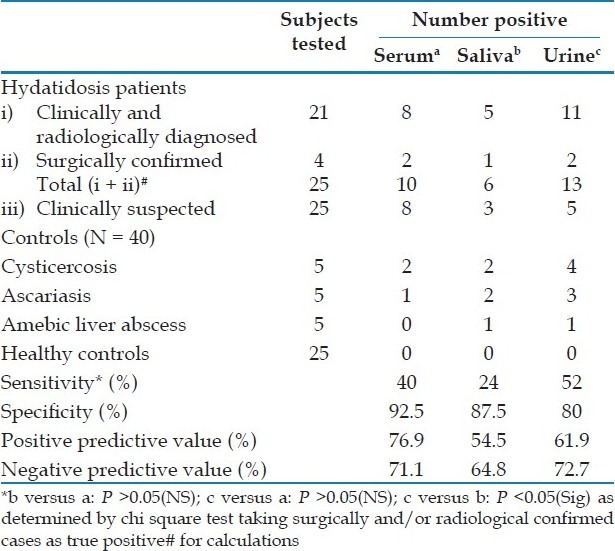

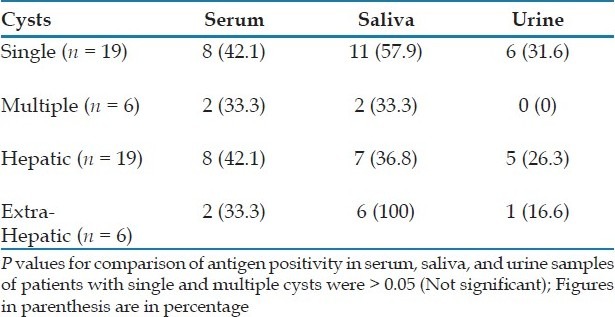

The hydatid antigen was detected in 18 (36%) serum, 9 (18%) saliva, and 18 (36%) urine samples of 50 patients, clinically suspected to be with hydatidosis. Among the four surgically confirmed cases, one was positive for antigen in the serum and urine samples, one only in the serum, one in the urine and saliva, while one patient did not show antigen in any sample [Table 1]. Among the 21 clinically and radiologically diagnosed cases, eight (38.09%) were positive for antigen in the serum, five (23.8%) in the saliva, and 11 (52.38%) in the urine. Overall, the sensitivity of antigen detection was found to be 52% in urine, 40% in serum, and 24% in saliva [Table 1]. The positivity in the saliva and urine samples was not statistically different from that of the serum (P.0.05). However, the positivity in the urine was significantly higher than in saliva (P<0.05). The difference was not statistically significant for saliva versus serum and urine versus serum, but significant for urine versus saliva. The antigen positivity in serum, saliva, and urine, in patients with single hydatid cysts was not significantly different from those in patients with multiple hydatid cysts [Table 2]. Similarly the antigen positivity in the serum and saliva samples of patients with hepatic cysts was not found to be significantly different (P>0.05) from those with extrahepatic cysts. However, antigen positivity in urine was significantly higher in hepatic cysts as compared to extrahepatic cysts [Table 2].

Table 1.

Hydatid antigen detection by ELISA in patients and controls

Table 2.

Antigen positivity in hydatidosis patients with single and multiple cysts and hepatic and extrahepatic cysts

Two out of five (40%) patients with cysticercosis, one out of five (20%) with ascariasis, and none with amebiasis showed antigen in the serum. On the other hand, two out of five (40%) patients with cysticercosis, two out of five with ascariasis (40%), and one out of five patients with amebiasis (20%) showed positive antigen in saliva; and four out of five (80%) patients with cysticercosis, three out of five (60%) with ascariasis, and one out of five (20%) patients with amebiasis showed antigen in the urine. None of the healthy controls was positive for antigen in serum, saliva or urine samples. Thus, the specificity of antigen detection was highest with the use of serum (92.5%) followed by saliva (87.5%) and urine (80%).

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis (CE) mainly depends on the radiological, immunological, and molecular techniques. Radiological techniques are either too expensive or the radiological picture may mimic other pathologies. Therefore, the routine laboratory diagnosis of CE is heavily reliant on serological tests, based on the detection of specific antibodies or circulating hydatid antigens.[3,7] One of the main problems of antibody detection is that around 40% of the surgically confirmed patients fail to show antibodies by various techniques.[3,7–11] Moreover, the antibodies may persist for a long time, even after removal of the cyst by surgery or after clinical cure by chemotherapy.[3,6] On the other hand, the circulating hydatid antigen is present in the active or recent infection and is absent in patients treated with surgery or chemotherapy.[7,12] Therefore, demonstration of the circulating antigen in the serum may indicate recent and active infection and may also help in monitoring the efficacy of chemotherapy.

In the present study, the diagnostic sensitivity of ELISA for antigen detection with the use of serum samples was 40%, which was similar (44%) to that reported by Ferragut et al., 1996,[22] but lower than that reported in other studies.[7,23,24] In other studies, a sensitivity of 55.55% was reported by Counter current immunoelectrophoresis (CIEP),[23] 95% by coagglutination (Co-A),[24] and 72% by Latex agglutination test.[11] The reason for low sensitivity was explained by the formation of Ag-Ab complexes in the serum.[7,25–27] Probably as a result of the breaking down of these complexes in the urine, free hydatid antigen became detectable in the urine, which could be the reason for the higher sensitivity of antigen detection in urine (84%). Thus, either detection of the circulating immune complexes or breakdown of immune complexes, for example, by PEG, before detection of antigen in the serum could be more helpful.

In the present study, the specificity of antigen detection in the serum was 92.5%, which was similar to that (91.7%) reported by Ferragut et al., 1996;[22] false positive reactions were seen in 20% of the cases from other parasitic diseases, but none in the healthy controls.

Detection of hydatid antigen excreted in the urine is the most recent approach for the diagnosis of parasitic infections.[3,16,28] It is believed that the parasite antigens, which are circulating in the serum, are also excreted in the urine. ELISA, Co-A, and CIEP are the common methods employed for urinary hydatid antigen detection. Hydatid antigen detection in urine indicated 43.75% sensitivity in surgically confirmed hydatid disease cases, 40% in ultrasound-proven cases, and 57.14% in clinically diagnosed hydatid disease patients, by CIEP.[29] In this study, no cross reactions were observed with other parasitic diseases, however, 8% false positive reactions were seen in healthy controls. In another study Co-A detected excreted hydatid antigen in 43.8% surgically confirmed cases, 60% ultrasound-proven cases, and 57.1% clinically diagnosed cases of CE.[28] In this study, false positive reactions were observed in 12.5% of other parasitic diseases and 12% of urine samples from healthy controls. In another study, all the cases of CE (confirmed surgically), which had hydatid antigen in the serum also showed antigen in the urine by Co-A, showing 100% sensitivity and specificity of urinary antigen detection.[16] In the present study the sensitivity of ELISA for hydatid antigen detection in urine samples was 50% in surgically confirmed cases, 52.4% in radiologically diagnosed cases, and 20% in clinically suspected cases. False positive reactions were high and seen in 53.3% of other parasitic disease controls, whereas, none of the healthy controls were positive.

There are no previous studies where saliva has been used for detecting hydatid antigen for the diagnosis of CE. In the present study, the sensitivity of ELISA for antigen detection in saliva samples is significantly low (25%) in surgically confirmed cases and 24% in clinically and radiologically diagnosed patients. False positive reactions were seen in 33.3% of other parasitic disease controls. None of the healthy controls were positive.

Various authors have reported hepatic cysts to be more immunogenic than extrahepatic cysts.[1] In the present study, there was no significant difference (P>0.05) in antigen positivity in the hepatic and extrahepatic cysts, either in the serum or saliva samples. However, antigen positivity in the urine was significantly higher (P<0.05) in the hepatic cysts than in the extrahepatic cysts. Also, there was no significant difference in antigen positivity in the serum, saliva or urine samples, from patients with single and multiple cysts.

The present study is the first report to investigate the usefulness of saliva samples for the detection of hydatid antigen for the diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. The results of the present study shows that saliva, when used alone, may not be a suitable sample for the detection of the hydatid antigen. However, if both the serum and urine samples are available for antigen detection, then the sensitivity of the test increases from 40% (only serum) to 72% (18 / 25) and if all the three samples are available, then the sensitivity increases even further to 76% (19/25). We have used the same samples for antibody detection by ELISA. The sensitivity of antibody detection in the serum, saliva, and urine samples was found to be 72, 56, and 84%, respectively, while the corresponding specificity was 76% for all three samples.[15] If antigen detection is combined with antibody detection, the sensitivity for serum, saliva, and urine samples rises to 72, 68, and 88%, respectively.

In conclusion, samples such as saliva and urine can be used either as adjuncts or as alternatives to the serum sample, for the detection of the hydatid antigen, with reasonable sensitivity and specificity, particularly in remote rural areas, where serum collection by venepuncture may not be possible. As hydatidosis is more common in sheep rearing and other rural settings, these observations become more relevant. Further research efforts should be directed toward investigating higher number of urine, saliva, and serum samples for hydatid antigen and antibody detection, to determine the best possible tests for the diagnosis of hydatidosis and also for epidemiological studies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.McManus DP, Zhang WM, Li J, Bartley PB. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1295–304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. WHO informal working group on echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:231–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parija SC. A review of some simple immunoassays in the serodiagnosis of cystic hydatid disease. Acta Tropica. 1998;70:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khurana S, Das A, Malla N. Increasing trends in seroprevalence of human hydatidosis in North India : A hospital based study. Trop Doct. 2007;37:100–2. doi: 10.1177/004947550703700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia LS. Tissue cestodes: Larval forms. In: Garcia LS, editor. Diagnostic medical Parasitology. 5th edition. Washington DC, USA: ASM Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray R, De PK, Karak K. Combined role of casoni test and indirect haemagglutination test in the diagnosis of hydatid disease. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig PS. Detection of specific circulating antigen, immune complexes and antibodies in human hydatidosis from Turkana (Kenya) and Great Britain, by enzyme-immunoassay. Parasite Immunol. 1986;8:171–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1986.tb00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickard MD, Lightowlers MW. Immunodiagnosis of hydatid disease. In: Thompson RC, Unwin A, editors. The Biology of Echinococcus and Hydatid Disease. London: Allen and Unwin; 1986. pp. 217–49. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddison SE, Slemenda SB, Schantz PM, Fried JA, Wilson M, Tsang VL. A specific diagnostic antigen of Echinococcus granulosus with an apparent molecular weight of 8 kDa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:377–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Force L, Torres JM, Carrillo A, Busca J. Evaluation of eight serological tests in the diagnosis of human echinococcosis and follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:473–80. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lightowlers MW, Gorttstein B. Echinococcosis / hydatidosis : Antigens, immunological and molecular diagnosis. In: Thompson RC, Lymbery AJ, editors. Echinococcus and Hydatid Disease. Oxon UK: CAB International; 1994. pp. 355–410. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devi CS, Parija SC. A new serum hydatid antigen detection test for diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:525–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortimer PP, Parry JV. Non-invasive virological diagnosis: Are saliva and urine specimens’ adequate substitutes for blood? J Med Virol. 1991;1:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Needham CS, Lillywhite JE, Beasley NM, Didier JM, Kihamia CM, Bundy DA. Potential for diagnosis of intestinal nematode infection through antibody detection in saliva. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:526–30. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunita T, Dubey ML, Khurana S, Malla N. Specific antibody detection in serum, urine and saliva samples for the diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Acta Tropica. 2007;101:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadaka HA, Khalifa AM, Eldein SZ, Taha K, Eldein KM. Urinary antigen detection for diagnosis of hydatid disease. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2002;32:69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mestecky J. Saliva as a manifestation of the common mucosal immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:184–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connell JA, Parry JV, Mortimer PP, Duncan J. Novel assay for the detection of immunoglobulin G antihuman immunodeficiency virus in untreated saliva and urine. J Med Virol. 1993;41:159–64. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maizels RM, Blaxter ML, Robertson BD, Selkirk ME. Parasite Antigens Parasite Genes: a Laboratory Manual for Molecular Parasitology. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1991. Antibody purification; pp. 44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voller A, Bidwell DE, Barlett A. Enzyme immunoassay in diagnostic medicine: Theory and practice. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;53:55–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravinder PT, Parija SC, Subba Rao KS. Urinary hydatid antigen detection by coagglutination, a cost-effective and rapid test for diagnosis of cystic Echinococcosis in a rural or field setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2972–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2972-2974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferragut G, Nieto A. Antibody response of Echinococcus granulosis infected mice: recognition of glucidic and peptidic epitopes and lack of avidity maturation. Parasite Immunol. 1996;18:393–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1996.d01-125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shariff M, Parija SC. Counter current immunoelectrophoresis test for serodiagnosis of hydatid disease by detection of circulating hydatid antigen. J Med Microbiol. 1991;14:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shariff M, Parija SC. Co-agglutination test for circulating antigen in hydatid disease. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:391–4. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-6-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pini C, Pastore R, Valesini G. Circulating immune complexes in sera of patients infected with Echinococcus granulosae. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;51:572–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig PS, Nelson GS. The detection of circulating antigen in human hydatid disease. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:219–27. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1984.11811805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig PS. Detection of specific circulating antigen, immune complexes and antibodies in human hydatidosis from Turkana (Kenya) and Great Britain, by enzyme-immunoassay. Parasite Immunol. 1986;8:171–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1986.tb00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadaka HA, Khalifa AM, Eldein SZ, Taha K, Eldein KM. Urinary antigen detection for diagnosis of hydatid disease. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2002;32:69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parija SC, Ravinder PT, Rao KS. Detection of hydatid antigen in urine by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1571–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1571-1574.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]