Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Cryptosporidiosis is a very important opportunistic infection and is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in HIV/AIDS patients. The objective of this study is to evaluate Ziehl-Neelsen staining, auramine phenol staining, antigen detection enzyme linked immunosorbent assay and polymerase chain reaction, for the diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis.

Materials and Methods:

The study was designed to determine the efficacy of modified Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN), Auramine-Phenol (AP) staining, antigen detection enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of cryptosporidia in 671 HIV-seropositive patients, 353 HIV-seronegative patients including 198 children with diarrhea and 50 apparently healthy adults.

Results:

Cryptosporidium was detected in 26 (3.9%), 37 (5.5%), 32 (4.8%) and 40 (6%) HIV-seropositive and 8 (2.3%), 10 (2.9%), 9 (2.6%) and 9 (2.6%) HIV-seronegative patients by ZN staining, AP staining, antigen detection ELISA and PCR, respectively. None of the healthy controls were infected with Cryptosporidium. Based on criteria of ‘true positive’ samples, i.e. positive by any two of the four techniques out of ZN, AP, antigen detection ELISA and PCR, sensitivity of ZN and ELISA was 79.06% and 95.35% respectively. AP and PCR were found to be 100% sensitive. Specificity of ZN and ELISA was 100% while specificity of AP and PCR was 99.59% and 99.39% respectively.

Conclusions:

Auramine phenol staining is a rapid, sensitive and specific technique for diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis.

KEY WORDS: Antigen detection, auramine phenol, Cryptosporidium, polymerase chain reaction, Ziehl Neelsen staining

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidium has emerged as an important cause of diarrheal illness worldwide, especially among young children and patients with immune deficiencies.[1] The spectrum of intestinal infection ranges from asymptomatic carrier state to severe diarrhea, depending upon the nutritional and immune status of the host and may also vary with infecting species.[2] In developing countries, the parasite is reported in 24% (range, 8.7-48%) of HIV-seropositive patients and children while in India, it has been reported in 2-36% of such patients.[1–6]

Laboratory diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis conventionally relies on demonstration of oocysts in stool samples by modified Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining. However, microscopic examination of ZN-stained smears is time-consuming, tedious and has low sensitivity of 37-90%.[5,7,8] Immunological methods to detect Cryptosporidium copro-antigen have been developed but variable sensitivity and specificity of these tests has been reported with different kits.[5,9–11] In addition, the detection limit of ZN staining and ELISA has been reported to be as low as 3×105-106 oocysts/ml of feces.[12] PCR assays have been used for diagnosis and shown to be more sensitive (97-100%) and specific (100%) than microscopy and ELISA, with analytical sensitivity of 50-500 oocysts/ml of liquid stool.[12,13] However, need of expertise, cost and availability of reagents has hampered its routine use in the diagnostic laboratories. Thus, one inexpensive approach is to use non-specific fluorescent stains such as auramine-rhodamine or auramine-phenol (AP), which gives yellow fluorescence to Cryptosporidium oocysts. Stained slides can be examined at lower power (×200 and ×400) of fluorescent microscope and appropriately sized (4-6 μm) round or slightly oval structures can be suspected of being Cryptosporidium oocysts. Moreover, detection efficiency of auramine phenol (1×103 oocysts/g) has been reported to be good but there are no reports of its comparison with ELISA and PCR.[14]

Thus, the present study was designed to evaluate two staining techniques (ZN and AP), antigen detection ELISA and PCR for the detection of intestinal cryptosporidia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study was carried out on stool samples collected during 2008-2009 in the Department of Parasitology, PGIMER, Chandigarh. The study group included 1074 individuals comprising 671 HIV-seropositive patients with or without diarrhea and attending the immunodeficiency clinic, 353 HIV-seronegative patients including 198 children with diarrhea and 50 HIV-seronegative and apparently healthy individuals without any history of diarrhea. All the subjects were attending the inpatient and outpatient departments of PGIMER, Chandigarh. After obtaining informed consent from each patient, the demographic characters and relevant symptoms were recorded on preplanned proforma.

Stool specimens and processing

Fecal samples were collected in clean, wide-mouthed plastic containers. All samples were subjected to formalin-ether concentration (centrifugation at 500×g for 10 min) and examined as wet saline and iodine preparation and permanent staining for the detection of parasites. Two dried smears were prepared from fecal concentrate for special staining of coccidian parasites. A portion of unconcentrated stool samples was stored at –20°C without any preservative for antigen detection and PCR.

Special staining for intestinal coccidia[12]

Two air-dried smears prepared from stool concentrate were fixed with methanol and then stained separately by cold-strong Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast stain, ZN) and Auramine ‘O’-phenol (fluorescent stain, AP) staining techniques. ZN-stained smears were examined under oil immersion of light microscope, while AP -stained smears were examined under 20x or 40x objectives of fluorescent microscope (excitation wavelength 350 nm, emission wavelength 450 nm).

Antigen detection

Cryptosporidium antigen was detected by using a commercial ELISA kit for stool samples (IVD Research Inc. CA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction

Stool samples from all the patients and healthy individuals were tested for the presence of Cryptosporidium DNA by nested PCR.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from stool samples stored at –20°C by using QIAmp DNA stool mini-kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions with some modifications i.e. initial boiling in 10% PVPP for 10 min to remove PCR inhibitors and samples were heated at 90°C for 5 min in lysis buffer to release Cryptosporidium DNA out of hard oocyst walls.

Nested PCR[15]

The primer pairs used in this nested PCR detect all the Cryptosporidium species known to cause infections in humans. In this 834-bp segment of the Cryptosporidium small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene was amplified by nested PCR. The primers, reaction mixture and incubation conditions were similar to as used earlier.

PCR products were analyzed using 1% agarose gel by ethidium bromide staining.

Statistics

Data was analyzed using SPSS for Windows Version 16.0 (TEAM EQX). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive values of different diagnostic techniques were determined by standard formula. Significance testing was done using Chi square test with GraphPad software.

RESULTS

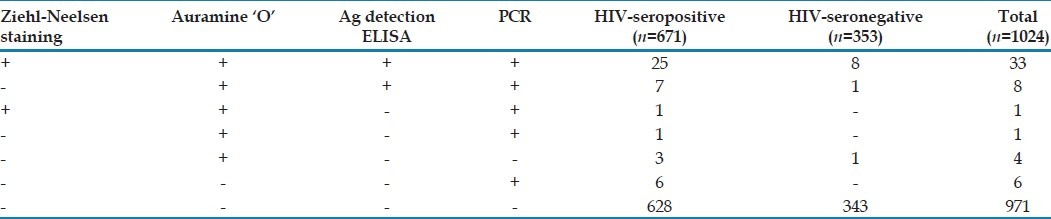

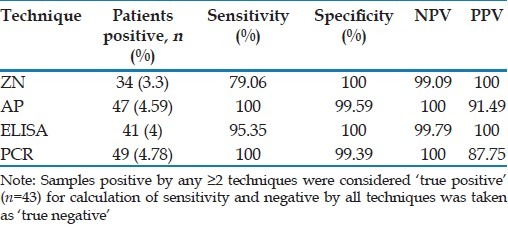

Cryptosporidium was detected in 26 (3.9%), 37 (5.5%), 32 (4.8%) and 40 (6%) HIV-seropositive and 8 (2.3%), 10 (2.9%), 9 (2.6%) and 9 (2.6%) HIV-seronegative patients by ZN staining, AP staining, antigen detection ELISA and PCR, respectively. None of the healthy controls was infected with Cryptosporidium [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Cryptosporidium positivity by any one or more techniques

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of modified Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN), Auramine phenol (AP), antigen detection (ELISA) and PCR for detection of Cryptosporidium in HIV-seropositive patients (n=671) and HIV-seronegative patients with diarrhea (n=353)

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of various techniques

For the assessment of these parameters, the criteria of ‘true positive’ was formulated on the basis of positivity by any two or more of the techniques (ZN staining, AP staining, ELISA and PCR), which was taken as “Gold Standard”. Thus a total of 43 samples were ‘true positive’ for Cryptosporidium. On comparison of different techniques based on “gold standard”, sensitivity of ZN staining and antigen detection ELISA was 79.06% and 95.3% respectively [Tables 1 and 2]. AP staining and PCR were 100% sensitive. Specificity of both ZN staining and Ag detection ELISA was 100% while specificity of AP staining and PCR was 99.6% and 99.4% respectively.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, reports of comparison of these four techniques i.e. modified ZN staining, rapid AP staining, antigen detection ELISA and PCR for the diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis are lacking. In the present study we have evaluated these four techniques in HIV-seropositive, HIV-seronegative and healthy subjects so as to find out the best, cheap and reliable method for the diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis.

In our study, Cryptosporidium was detected in 26 (3.9%) HIV-seropositive and 8 (2.3%) HIV-seronegative patients by ZN staining. In previous studies from India, it was reported in 3.7-36.22% of HIV-seropositive patients,[4–7] and 0.06-13% of HIV-seronegative patients with diarrhea.[5,14,16,17] In our study, ZN staining has been found to be 100% specific with sensitivity of 79.06% which is in accordance with previous studies where ZN staining has been found to be 98.9-100% specific with sensitivities ranging from 37-90%.[5,7,8] With ZN staining, difficulties arise due to poor uptake of stain by oocysts sometimes, in discriminating between Cryptosporidium oocysts and other spherical objects of similar size (yeasts) staining dull red.

Cryptosporidium oocysts stained with AP appear ring-shaped (4-6 μm in diameter) and exhibit a characteristically bright yellow fluorescence. In the present study, AP staining had 100% sensitivity, which is in accordance with earlier studies and may be attributed to the fact that it stains oocyst outer wall as well as internal structures and phenol accelerates AP penetration through oocyst walls.[12] Cryptosporidium oocysts stain against a dark background and the smears can be easily examined under 20X or 40X objective.[12,18,19] In our study, the specificity of AP was 99.6% which is similar to that reported by Kang and Mathan.[19] Thus AP is better than ZN due to high sensitivity and almost comparable specificity; lower screening time per smear (30 sec vs. 7 min) and screening at low magnification (×400).

Oocysts might not be detectable in clinical samples from all cryptosporidiosis cases and in such cases copro-antigen detection assays and PCR-based methods (nested PCR being more sensitive) have high diagnostic index.[12] Antigen assays have an advantage of not requiring skills in microscopic identification of organisms and their specificity has been reported to be high.[12] However, variable sensitivities (66.3-100%) and specificities (93-100%) have been reported using different kits.[20,21] In our study, Cryptosporidium antigen detection ELISA was 100% specific with a s ensitivity of 95.35%. The commercially available copro-antigen detection ELISA formats use monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) which recognize different sets of surface epitopes and mAbs used in these ELISA kits may not react or react weakly with antigens of different Cryptosporidium species. In addition the cost of test per sample has been reported to be much more than microscopic examination. Thus, ELISA appears to offer no increase in sensitivity over microscopy especially in comparison to AP.[12]

PCR-based methods are reported to be more sensitive than conventional and immunological assays for detecting Cryptosporidium oocysts in feces.[5,12] Similar to previous studies from India[5] and other parts of the world,[8] PCR showed high sensitivity (100%) while specificity was 99.4%. Thus, PCR is less specific (99.4%) than ZN (100%), ELISA (100%) and AP (99.6%) but has high sensitivity similar to AP staining. Moreover, the cost of PCR, time taken for each reaction and expertise is highest amongst all the four techniques used in the current study. Molecular methods are restricted to specialist laboratories, but are necessary to determine Cryptosporidium species/genotypes and subtypes.

In conclusion, this study shows that AP, a simple fluorescent staining, is highly sensitive, specific, cost-effective and less time-consuming. Thus for the diagnosis of intestinal cryptosporidiosis we can rely on AP staining technique. However, for the identification of Cryptosporidium species/genotypes molecular techniques are indispensable.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The work has been supported by institutional Research Grant of Post Graduate of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nichols G. Epidemiology. In: Fayer R, Xiao L, editors. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. 2nd ed. New York: CRC Press; 2008. pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren CA, Guerrant RL. Clinical disease and pathology. In: Fayer R, Xiao L, editors. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. 2nd ed. New York: CRC press; 2008. pp. 235–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushen OY, Kohli A, Pinkerton RC, Dupnik K, Newman RD, Sears CL, et al. Heavy cryptosporidial infections in children in northeast Brazil: Comparison of Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi M, Chowdhary AS, Dalal PJ, Maniar JK. Parasitic diarrhoea in patients with AIDS. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaushik K, Khurana S, Wanchu A, Malla N. Evaluation of staining techniques, antigen detection and nested PCR for the diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis in HIV seropositive and seronegative patients. Acta Trop. 2008;107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulkarni SV, Kairon R, Sane SS, Padmawar PS, Kale VA, Thakar MR, et al. Opportunistic parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients presenting with diarrhoea by the level of immunesuppression. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuli L, Singh DK, Gulati AK, Sundar S, Mohapatra TM. A multiattribute utility evaluation of different methods for the detection of enteric protozoa causing diarrhea in AIDS patients. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan UM, Pallant L, Dwyer BW, Forbes DA, Rich G, Thompson RC. Comparison of PCR and microscopy for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in human fecal specimens: Clinical trial. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:995–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.995-998.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graczyk TK, Owens R, Cranfield MR. Diagnosis of subclinical cryptosporidiosis in captive snakes based on stomach lavage and cloacal sampling. Vet Parasitol. 1996;67:143–51. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayalakshmi J, Appalaraju B, Mahadevan K. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunoassay for the detection of Cryptosporidium antigen in fecal specimens of HIV/AIDS patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:137–8. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.40427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehl KS, Cicirello H, Havens PL. Comparison of four different methods for detection of Cryptosporidium species. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:416–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.416-418.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith H. Diagnostics. In: Fayer R, Xiao L, editors. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. New York: CRC Press; 2008. pp. 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong J, Olano JP, McBride JW, Walker DH. Emerging pathogens: Challenges and successes of molecular diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:185–97. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malla N, Sehgal R, Ganguly NK, Mahajan RC. Cryptosporidiosis in children in Chandigarh. Indian J Med Res. 1987;86:722–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao L, Bern C, Limor J, Sulaiman I, Roberts J, Checkley W, et al. Identification of 5 types of Cryptosporidium parasites in children in Lima, Peru. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:492–7. doi: 10.1086/318090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajjampur SS, Gladstone BP, Selvapandian D, Muliyil JP, Ward H, Kang G. Molecular and spatial epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in children in a semiurban community in South India. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:915–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01590-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pal S, Bhattacharya SK, Das P, Chaudhuri P, Dutta P, De SP, et al. Occurrence and significance of Cryptosporidium infection in Calcutta. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:520–1. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanscheid T, Cristino JM, Salgado MJ. Screening of auramine-stained smears of all fecal samples is a rapid and inexpensive way to increase the detection of coccidial infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang G, Mathan MM. A comparison of five staining methods for detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in fecal specimens from the field. Indian J Med Res. 1996;103:264–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia LS. In Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. 5th ed. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2007. Intestinal protozoa (Coccidia and Microsporidia) and Algae; pp. 57–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Division of Parasitic Diseases. Cryptosporidiosis. [Last accessed on 2010 Jul 8]; http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/DPDx/HTML/Cryptosporidiosis.htm . [Google Scholar]