Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Opportunistic parasitic infections are among the most serious infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patients and claim number of lives every year. The present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites and to elucidate the association between intestinal opportunistic parasitic infection and CD4 (CD4+ T lymphocyte) counts in HIV-positive patients.

Materials and Methods:

The study was done on 266 HIV-positive patients presenting with diarrhoea and 100 HIV-positive patients without diarrhoea attending the integrated counselling and testing centre (ICTC) of SMS hospital, Jaipur. Simultaneously, CD4+ T-cell count estimation was done to assess the status of HIV infection vis-à-vis parasitic infections. The identification of pathogens was done on the basis of direct microscopy and different staining techniques.

Results:

Out of 266 patients with diarrhoea, parasites were isolated from 162 (i.e. 60.9%) patients compared to 16 (16%) patients without diarrhoea. Cryptosporidium parvum (25.2%) was the predominant parasite isolated in HIV-positive patients with diarrhoea followed by Isospora belli (10.9%). Parasites were more commonly isolated from stool samples of chronic diarrhoea patients, (77% i.e. 128/166) as compared to acute diarrhoea patients (34% i.e. 34/100) (P<0.05). The maximum parasitic isolation was in the patients with CD4+ T cell counts below 200 cells/μl.

Conclusions:

Chronic diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <200/μl has high probability of association with intestinal parasitic infections. Identification of these parasitic infections may play an important role in administration of appropriate therapy and reduction of mortality and morbidity in these patients.

KEY WORDS: Diarrhoea, CD4+ T-cell counts, Coccidian parasites, HIV

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, a worldwide phenomena, is a serious public health problem.[1] HIV infection has globally claimed over 20 million lives and over 40 million people carry the infection.[2] India remains a low prevalence country with over all HIV prevalence of 0.9%; however, it masks various sub-epidemics in various foci in the country as indicated by the sentinel surveillance data.[3]

Since the beginning of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic, opportunistic infections (O.Is) have been recognized as common complications of HIV infection.[4] The spectrum of O.Is in the HIV-infected patients varies from one region to another. Gastrointestinal infections are very common in patients with AIDS. Diarrhoea is a common clinical presentation in HIV infected patients. Reports indicate that diarrhoea occurs in 30-60% of AIDS patients in developed countries and in about 90% of AIDS patients in developing countries.[5]

The etiological spectrum of enteric pathogens causing diarrhoea includes bacteria, parasites, fungi, and viruses.[6] The presence of opportunistic parasites Cryptosporidium parvum, Cyclospora cayetanensis, Isospora belli, and Microsporidium sp is documented in patients with AIDS.[7] Non-opportunistic parasites such as Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia intestinalis, Trichuris trichura, Ascaris lumbricoides, Strongyloides stercoralis, and Ancylostoma duodenale are frequently encountered in developing countries but are not currently considered opportunistic in AIDS patients.[8]

Cryptosporidiosis and isosporiasis are both caused by protozoan parasites. These diseases are easily spread by contaminated food or water or by direct contact with an infected person or animal. The living conditions of the people have a great influence on the transmission of these parasitic infections in a community. Both cause diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, and stomach cramps. In people with a healthy immune system, these symptoms do not last for more than 14 days but when the immune system is damaged, these symptoms can continue for a long time. Diarrhoea can interfere with the absorption of nutrients and this can lead to weight loss.

The degree of immune-suppression, as defined by the CD4+ T-cell count, determines to a large extent when individuals with HIV infection will develop opportunistic infections. The incidence and outcome of many of these complications, however, can be altered by preventive measures, in particular primary and secondary prophylaxis.

At present, the initiation of primary prophylactic therapies for O.Is is based chiefly on the absolute CD4+ T-cell count which has been shown to be an excellent predictor of the short-term overall risk of developing AIDS among HIV-infected patients.[9] A decrease in CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts is responsible for the profound immunodeficiencies that lead to various O.Is in HIV-infected patients.[10]

There have been reports on frequency of various pathogens causing diarrhoea from different parts of India. However, there appears to be a paucity of data on correlation of CD4+ T-cell counts and the etiology of dairrhoea among the HIV patients in this part of India. Thus, this study was conducted to isolate and identify the opportunistic protozoans affecting the HIV patients and to co-relate the presence of these parasites with the type of diarrhoea and CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study was conducted from Jan 2009 to Dec 2009 in the integrated counselling and testing centre (ICTC), Department of Microbiology, SMS Medical College, Jaipur. The study group included

100 HIV-positive patients presenting with acute diarrhoea

166 HIV-positive patients presenting with chronic diarrhoea

Controls: 100 HIV-positive patients without diarrhoea.

Demographic data including a structured questionnaire was filled.

Inclusion criteria

Diarrhoea was defined as two or more liquid or three or more soft stools per day. The duration and frequency of diarrhoea were noted to classify it as acute if it is lasted for less than 1 month and chronic if it is lasted for more than 1 month.[11]

Exclusion criteria

Persons who received antiparasitic treatment for diarrhea in the past 14 days were excluded.

Stool examination

Patients were given labeled, leakproof, clean sterile plastic containers to collect stool samples (10% formol saline was used to preserve stool samples). The consistency of stool samples was noted. A direct wet mount of stool in normal saline (0.85%) was prepared and examined for the presence of motile intestinal parasites and trophozoites under light microscope. Lugol's iodine staining was used to detect cysts of intestinal parasites. The modified acid fast staining technique was used for coccidian parasites (Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Isospora) after concentration by the formol–ethyl acetate technique.[12] Chromotrope 2R Staining was done by the “Quick Hot Gram Chromotrope 2 R” technique for microsporidial spores. After heat fixing the smear (3 times for 1 second each), all steps of gram staining were done, leaving the safranin step. The slide was placed in warmed (50° to 55°C) chromotrope stain for 1 min and then rinsed in 90% acid-alcohol for 1 to 3 s and in 95% ethanol for 30 seconds. Then it was rinsed twice, 30 s each time, in 100% ethanol. We observed the slide by light microscope in ×40 and ×100 objectives. Microsporidial spores appeared as dark staining violet ovoid structures against a pale green background. This newer method is very quick and highly sensitive for microsporidial spores.[13]

CD4+ T cell estimation

The CD4+ T-cell count estimation of the patients was done by the FACS count (Becten Dickinson, Singapore). Each time the patients gave their stool samples; their most recent CD4+T cell count was done for analysis.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done by using SPSS 13.0 version. Strength of association was measured by using the Chi–square test and its associated P value. Values were considered to be statistically significant when the P value was less or equal to 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 266 patients 184 (69.2%) were males and 82 (30.8%) females. The mean age of the male and female patients was 34.94±11.01 and 35.65±9.03 respectively. In the present study, most of the patients were males and in the age group of 31-40 years. Parasitic infections were detected in 60.9% of the stool samples of HIV-positive diarrhoea patients and in 16% of HIV-positive patients without diarrhoea (controls).

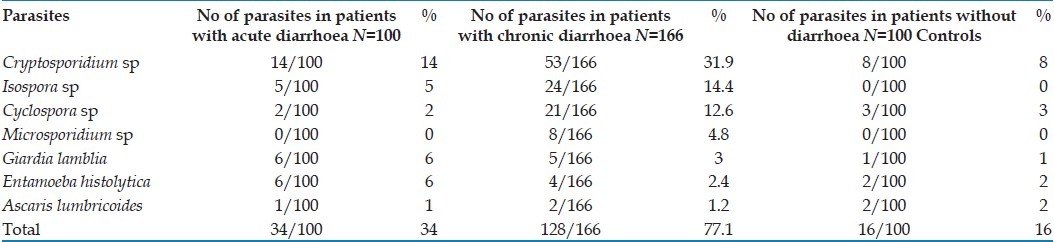

Cryptosporidium was the most common parasite, isolated in 67 (67/266 i.e. 25.2%) HIV-positive diarrhoea patients [Table 1]. Isospora, Cyclospora and microsporidia were isolated in 29 (10.9% i.e. 29/266), 23 (8.6% i.e. 23/266) and 8 (3% i.e. 8/266) diarrhoea patients, respectively. Other parasites like Giardia sp, E. histolytica, and Ascaris sp. were isolated from 11 (4.1% i.e. 11/266), 10 (3.7% i.e. 10/266), and 3 (1.1% i.e. 3/266) diarrhoea patients respectively. These parasites were isolated in 5% (5/100) of HIV-positive patients without (control group) as compared to 9% (24/266) in HIV-positive diarrhoea patients. Parasites were isolated from 34 (34% i.e. 34/100) acute diarrhoea HIV patients and 128 (77% i.e. 128/166) chronic diarrhoea patients in the present study group [Table 1]. There was a statistically significant difference in isolation rate of parasites in HIV positive, acute and chronic diarrhoea patients (P<0.05), the presence of parasites was more commonly associated with chronic diarrhoea. Isolation of coccidian (Cryptosporidium, Isospora, Cyclospora sp) parasites in particular was much higher in chronic diarrhoea (59.03%; 98/166) as compared to acute diarrhoea (21%; 21/100) cases.

Table 1.

Enteric parasites detected from HIV patients with and without diarrhoea

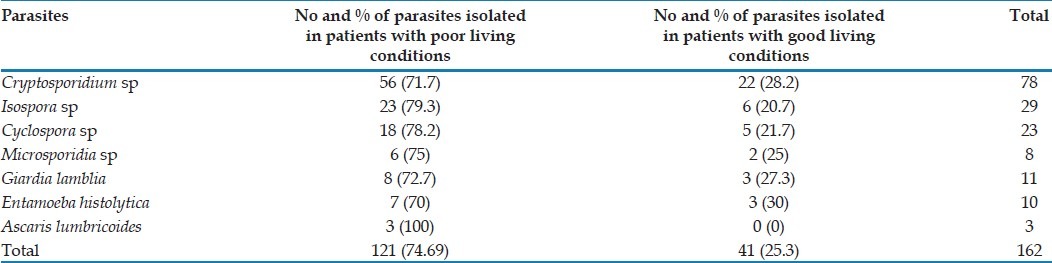

Out of total 162 parasite positive patients with diarrhoea, 121 (74.7%) were living in “poor” living conditions, whereas 41 (25.3%) were living in “good living” conditions [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of parasites in patients with respect to their living conditions

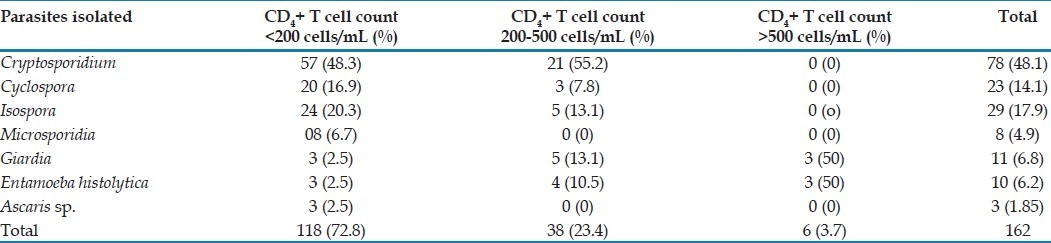

In 118 patients (72.8% of patients positive for parasite) the CD4+ T cells was <200 cells/μl while 38 (23.4%) had CD4+ T-cell count in the range of 200-500 cells/μl and 6 (3.7%) had CD4+ T-cell counts >500 cells/μl, respectively [Table 3]. The presence of opportunistic parasites in the HIV-positive patients with diarrhoea was inversely proportional to the CD4+ T-cell counts in these patients, i.e. the lower the CD4 counts the more were the chances of isolation of parasites in these patients.

Table 3.

Association between parasites isolated and CD4+ T-cell counts of HIV positive patients with diarrhoea

DISCUSSION

This study reports the prevalence of opportunistic and common intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-positive patients with and without diarrhoea. Since diarrhoea is an important manifestation of the intestinal parasitic infestation in HIV-infected patients, we compared the prevalence of these parasites in HIV-positive patients with and without diarrhoea (60.9% compared to 16% in patients with diarrhoea and without diarrhoea respectively) (P<0.05) [Table 1]. This association is in agreement with other studies which have shown that parasites are important etiological agents of diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients.[14–16]

In the present study, enteric parasites were detected in 60.9% of HIV-infected patients with diarrhoea and 16% in HIV-positive patients without diarrhoea. This study corroborates well with other studies which reported a prevalence of intestinal parasites, ranging from 30% to 60% in the HIV-positive diarrhoea patients.[15–18]

Cryptosporidium was found to be predominant (67/266 i.e. 25.2%) enteric parasite associated with diarrhoea. Although there was a difference in isolation rate in acute and chronic diarrhoea cases, it was not as large as with other protozoan parasites (which were more commonly isolated in chronic cases), which corroborates with earlier studies.[19] Cryptosporidium was isolated with a high frequency in both acute (14% i.e. 14/100) and chronic diarrhoea (31.9% i.e. 53/166) patients indicating an existing high risk of infection by this parasite in HIV-positive patients. Earlier studies done in southern India[16,18–20] have noted isolation of Cryptosporidium between 10% and 19% in HIV-positive diarrhea patients. Our study reports 25.2% of Cryptosporidium in stool of HIV-positive diarrhoea patients which is in consonance with other studies conducted in parts of northern India recently.[15,20] The difference in isolation rates in North and South India may be due to difference in levels of general hygiene and geographical location.

Earlier studies[16,19] in Chennai have reported microsporidia in only 6% and 0.98% of diarrhoea patients, though microsporidia was reported from 17% to 18% of HIV diarrhoea patients in Mumbai[21] and in 26.7% stool samples of HIV-positive diarrhoea patients in Varanasi.[15] In the present study, only 3% (8/266) of stool samples from HIV-positive diarrhoea patients were positive for microsporidia species. Lower isolation rates could be due to geographical variation and use of more specific, Chromotrope 2R staining method for parasite detection. Like earlier studies, this parasite was isolated only from stool samples of patients suffering from chronic diarrhoea.[15–17]

Earlier studies have reported Isospora as the most common parasite in stool samples of HIV-positive diarrhea patients.[16,19] In present study, Isospora was isolated from lower number 10.9% (29/266) of HIV-positive diarrhoea patients, slightly lower isolation rate as compared to earlier studies may be due to asymptomatic shedding of oocysts and treatment with trimethoprim sulphamethoxazole for other infections in AIDS cases, which may confer some protection against this parasite. Isospora was more commonly isolated from chronic diarrhoea patients. (14.4% in chronic diarrhoea as compared to 5% in acute diarrhoea patients).

Cyclospora was isolated in 0.98% and 4.9% of HIV positive diarrhoea patients in previous studies done in southern India.[17,18] In a recent study done in Varanasi, Cyclospora was isolated from stools of 24% HIV-positive diarrhoea patients.[15] In our study, Cyclospora was isolated from 8.6% (23/266) of HIV-positive diarrhoea patients. Cyclospora was more commonly associated with chronic diarrhoea patients (21/166 i.e. 12.6%) as compared to acute diarrhoea patients (2/100 i.e. 2%) which corroborates with other studies.[15] The difference in rates as compared to other studies may be attributed to geographical variation and also because of larger number (166/266) of chronic diarrhoea cases which increased the chances of isolation in the present study.

Data from various studies demonstrate striking geographic variations in the prevalence of individual pathogens in HIV-infected patients. These variations may relate both to the prevalence of pathogens within the community, the living conditions of the patients, and to drugs used prophylactically in patients with HIV infection and AIDS.

HIV opportunistic infections, cryptosporidiosis inclusive, tend to vary from one locality to another and from one country to another depending on the level of contamination in the water, food, and contact with animals, which are important factors in the dissemination of the parasite. Finally, the small size (3-5 μm) of oocysts, their resistance to chlorine disinfections, and low infective dose are the major infective potential of C. parvum. Our findings tend to support the view that more common parasites (G. lamblia, E. histolytica, and A. lumbricoides) are not opportunistic in patients with AIDS and identification of these common parasites at comparable levels in cases and controls reflects poor level of environmental hygiene.

In the present study, coccidian parasites were isolated in 59.6% (99/166) of chronic diarrhoea patients as compared to 21% (21/100) of acute diarrhoea patients (P<0.05) thus indicating their role in prolonging the duration of diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients.

In the present study, 77% and 34% is the isolation rate for parasites in chronic and acute diarrhoea patients respectively which corroborates with other studies.[6,9] Thus, there is a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) in the isolation rate of the parasite with respect to type of diarrhoea as seen in earlier studies.[15,19] The higher parasitic isolation in chronic diarrhoea cases (77%) as compared to acute diarrhea (34%) cases was because a majority of parasites isolated in the present study were of the coccidian group which are more frequently encountered in chronic diarrhoea cases except Cryptosporidium which is found with equal frequency in both type of diarrhoea[15–19] [Table 1]. The higher level of immunosuppression in the chronic cases predisposes them to infection by these opportunistic enteric parasites. Also these coccidian parasites are not controlled by empirical antidiarrhoeal drugs which are received by most of the chronic diarrhoea cases, these drugs definitely control the other intestinal parasites which show lower isolation rates in our study.

Out of 162 patients positive for parasites, 74.7% (121/162) lived in “poor” conditions (high degree of crowding, low quality of water supply, improper disposal of excreta and unfinished or semi-finished type of floor), thus indicating that improvement in hygienic conditions decreased the chances of parasitic infections in HIV patients, as reported by other studies.[22]

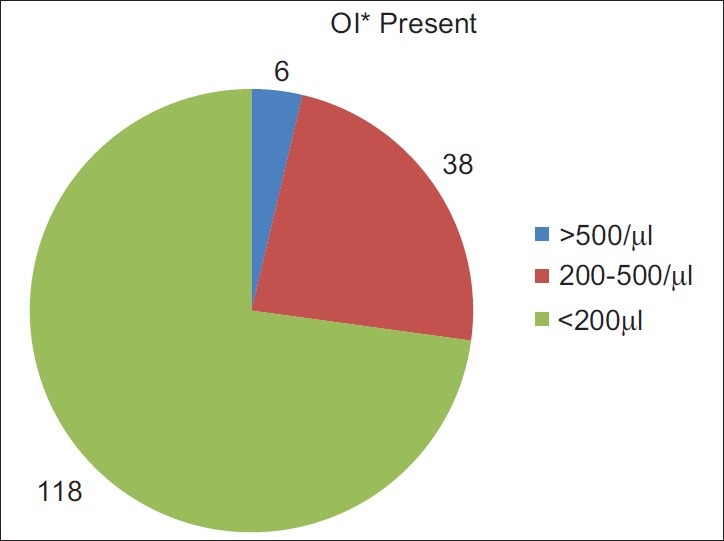

In present study 54% of patients showed CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/μl, 40% and 6% of patients had CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts between 200-500 cells/μl and >500 cells/ml, respectively. 72.8% (118/162) patients testing positive for parasites have CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/μl, while 27.1% (44/162) of patients have CD4+ T-cell counts in the range between 200-500 cells/μl and more than 500 cells/μl, cumulatively [Figure 1]. The median CD4+ count observed in the HIV-positive diarrheal group is 227.8586 cells/μl in our study which correlates with other studies.[15,18,23] In the present study, the relation between the CD4+ T cell counts and the presence of opportunistic parasites in stool samples of HIV-positive diarrhoeal patients is statistically significant (P<0.05) [Table 3]. The maximum isolation (72.8%) was at CD4+ T-cell counts <200/μl. Thus, the lower the CD4+ T-cell counts (<200 cells/μl) more are chances of isolation of these parasites in stool samples.[3]

Figure 1.

Presence of opportunistic infections in relation to CD4+ T-cell counts. *OI: Opportunistic infections

Limitations

There are some limitations of our study. It is possible that some parasites were not detected in this study because techniques such as the water-ether sedimentation method for microsporidia or adhesive tape or anal swab for Enterobius vermicularis were not used. Therefore, the prevalence of other intestinal parasites among the study participants may have been underestimated.

CONCLUSION

The high prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-positive patients warrants urgent need of intervention so as to avoid its consequences. Infection of Cryptosporidium, Isospora, Cyclospora, and microsporidia was significantly higher among HIV-positive subjects with diarrhoea, particular in those with lower CD4+ T-cell counts. Screening for these infections is therefore essential for early diagnosis and treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiwanitkit V. Intestinal parasitic infections in Thai HIV-infected patients with different immunity status. BMC Gastroenterol. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007. UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines on HIV testing manual. National AIDS control Organization. Ministry of health and family Welfare. Govt of India. [Last accessed on 2007 Mar]. Available from: http://nacoonline.org/AboutNACO/Policy-Guidelines/Policies .

- 4.Janoff EN, Smith PD. Perspectives on gastrointestinal infections in AIDS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1988;17:451–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Framm SR, Soave R. Agents of diarrhoea. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:427–47. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitra AK, Hernandez CD, Hernandez CA, Siddiq Z. Management of diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:630–9. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodgame RW. Understanding intestinal spore-forming protozoa: Cryptosporidia, microsporidia, Isospora and Cyclospora. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:429–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas SB. Missing infections in AIDS. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;8(Suppl 1):34–8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90453-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talib VH, Khurana SK, Pandey J, Verma SK. Current concepts: Tuberculosis and HIV infection. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1993;36:503–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein DS, Korvick JA, Vermund SH. CD4+ lymphocyte cell enumeration for prediction of clinical course of human immunodeficiency virus disease: A review. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:352–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talib SH, Singh J. A study on opportunistic enteric parasites in 80 HIV seropositive patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1998;41:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diagnostic procedures for stool specimens. [Last accessed on 2011 Jul 5]. Available from: http://www,dpd.cdc.gov .

- 13.Moura H, Schwartz DA, Bornay-llinares F, Sodre FC, Wallace S, Visvesara GS. A new and improved “quick-hot Gram-chromotrope” technique that differentially stains microsporidian spores in clinical samples, including paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:888–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lew FA, Poles MA, Dieterich DT. Diarrheal disease associated with HIV infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1997;26:259–90. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuli L, Gulati AK, Sundar S, Mohapatra TM. Correlation between CD4 counts of HIV patients and enteric protozoan in different seasons - an experience of a tertiary care hospital in Varanasi (India) BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhya A, Ramakrishnan BS, Kang G, Pulimood AB, Mathan MM, Zachariah A, et al. Enteric pathogens in southern Indian HIV-infected patients with and without diarrhoea. Indian J Med Res. 1999;109:85–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar SS, Ananthan S, Laksmi P. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV infected patients with diarrhoea in Chennai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vajpayee M, Kanswal S, Seth P, Wig N. Spectrum of opportunistic infections and profile of CD4+ counts among AIDS patients in North India. Infection. 2003;31:336–40. doi: 10.1007/s15010-003-3198-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar SS, Ananthan S, Saravanan S. Role of coccidian parasites in causation of diarrhoea in HIV infected patients in Chennai. Indian J Med Res. 2002;116:85–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballal M. Manuals on Indo-US Workshop on diarrhoea and enteric protozoan parasites. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2005. Opportunistic intestinal protozoal infections in HIV infected patients in a rural cohort population in Manipal, Karnataka-Southern India. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samantaray JC, Panda PL. Manuals on Indo-US Workshop on diarrhoea and enteric protozoan parasites. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2005. Spectrum of Intestinal Parasitosis in Immunocompromised Patients Suffering from Diarrhoea: With special reference to Cryptosporidium, Isospora, Cyclospora, microsporidia and Blastocystis. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tellez A, Morales W, Rivera T, Meyer E, Leiva B, Linder E. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in the human population of Leon, Nicaragua. Acta Trop. 1997;66:119–25. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamu H, Petros B. Intestinal protozoa infections among HIV positive persons with and without antiretroviral treatment (ART) in selected ART centers in Adama, Afar and Dire – Dawa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2009;23:133–40. [Google Scholar]