Abstract

Background:

In recent times, soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections seem to loose more and more interest due to the fact that resources are being justifiably diverted to more recent priorities such as HIV/AIDS and malaria. In developing countries, the upsurge of intestinal helminth infections constitutes a problem not only of public health concern but also of development.

Aim:

To find out the prevalence of STH infections in persons visiting the traditional health care centre in west Cameroon.

Materials and Methods:

In order to evaluate the prevalence and intensity of STH infections, in persons visiting the centre of phytomedecine, a parasitological investigation of feces was carried out in 223 stools, using three techniques (direct examination, concentration method of Willis, and Mc Master technique).

Results:

130 stools were collected from male and 93 from female subjects, hence a sex ratio of 1.4:1. Among the 223 stools examined, 97 specimens were found to be positive with one or several parasite species, thus giving a prevalence of 45.3%. The parasitism occurs from early age (1-10 years) reaching 4.5%. The most infected age group was 21-30 years (31%). Female subjects (28.3%) were statistically more infected than males (15.2%). The intestinal nematode species found were Trichuris trichiura (19.2%), Ascaris lumbricoides (13.4%), and hookworm (10.7%). These parasites occurred as single (19.2%) or multiple infections (10.3%). The mean fecal eggs count was 3722±672, 875±462, and 563±283 for A. lumbricoides, hookworm, and T. trichiura, respectively.

Conclusion:

These results show the necessity of the application of suitable measures which are aimed at reducing the extent of STH.

KEY WORDS: Ascaris lumbricoides, Cameroon, hookworm, soil-transmitted helminths, Trichuris trichiura

INTRODUCTION

Soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infection is most prevalent in humid, tropical, and subtropical regions of developing countries where adequate sanitation is lacking and the soil is sufficiently moist to allow survival of worm eggs or larvae, thereby allowing humans to come in contact with them through either soil or contaminated food.[1] These infections are responsible for misery, starvation, and often mortality in man.[2] The outbreak of STH infections is an important issue of public health in developing countries that has recently been neglected in favor of HIV/AIDS and malaria. The WHO reported that more than 1 billion people in the world are infected with intestinal helminths. Surveys conducted in China have revealed that more than 1 million people harbor gastrointestinal (GI) nematodes with both high prevalence and intensity.[3] In Ivory-Coast, about 36% children of school age are infected with GI helminths[4] while in Philippines 67% harbor STH infections.[5] In Cameroon, the Permanent Secretary of the National Programme of schistosomiasis and GI helminthiasis control reported in January 2006 that 2 million people were infected with schistosomes and more than 10 million with intestinal worms. These diseases affected especially school-age children and compromised their growth, intellectual development, and their school performance,; as well as increased the vulnerability of children to other diseases.[6] Thus, researches should be conducted for a better management of this parasitic issues in many countries to reduce or to eradicate if possible some of these infections. Keeping the above facts into consideration, the present study aims at evaluating the prevalence and intensity of intestinal nematodes in cameroonian habitants living in urban zone especially in Dschang and to identify the most common species.

STUDY AREA AND METHODS

Study area

This transversal study was carried out in Dschang situated in the Western Region of Cameroon. The mean altitude is about 1400 m above sea level. The climate is soudano-guinean modified with the altitude. The temperature varies between 15.4°C and 25°C, the relative humidity (RH) range from 64.3% to 97% and the rainfall between 0.4 and 50 mm.

METHODS

Parasitology

Subject consent was obtained from the relevant health and administrative authorities. The subjects involved in this study were recruited between March and August 2005 using the registration number at their arrival in the African Centre of Traditional Phytotherapy of the ALANGO Foundation. The data collected were the name and surname, the age and sex of the subject. Each person received a label plastic container (with an identification number) which had a capacity of 32 ml for the collection of fecal materials. All the stool samples were collected between 8.00 am and 12.00 am.

The specimens collected from each subject were immediately transported in ice bags to the Laboratory of Applied Biology and Ecology (LABEA) of the University of Dschang and were examined 24 h after their emission. For each specimen, a systematic macroscopically analysis was done to register the consistency of the fecal material, element present in the feces such as mucus, blood, and eventually worms (Taenia segment, adults of round worms) were also registered as outlined.[7] Then, feces was analyzed by the flotation technique using a saturated salt solution.[8] The intensity of the parasitic load was done using the Mc Master technique[7,8] and the parasitic stage identification was done using the morphological characteristic such as the form, the length, the nature of the egg shell, and the identification key.[7–9]

Data analysis

The comparison of the prevalence of worms and the mean intensity of infection was made using the chi-square test (χ2) and the analysis of variances (ANOVA) respectively at the P<0.05 significant level.

RESULTS

Subject distribution

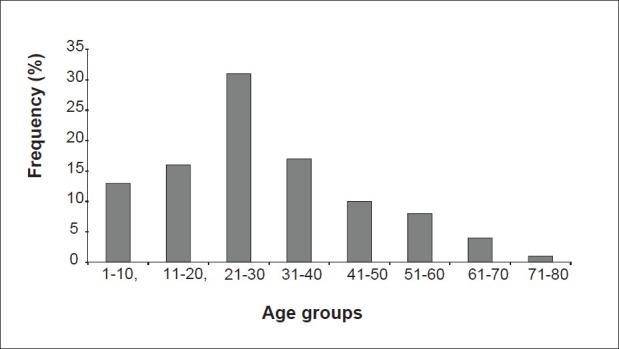

In this work, 223 fecal specimens were collected. Among this, 130 came from the males and 93 from females; hence a sex ratio of 1.4:1. The distribution of the study population according to age groups with the length of 9 years is illustrated in Figure 1. The modal age group was 21-30 (32.5%) years and thus, the young (about 61%) constituted the majority of the studied population.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the entire population of the study according to age groups

Overall prevalence

Out of the 223 fecal sample collected, 97 were positive and giving an overall prevalence of 43.5%.

According to age and sex

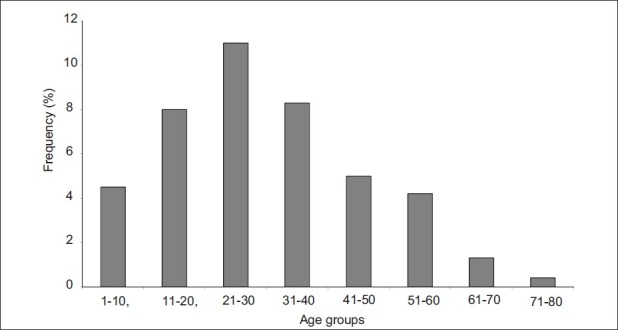

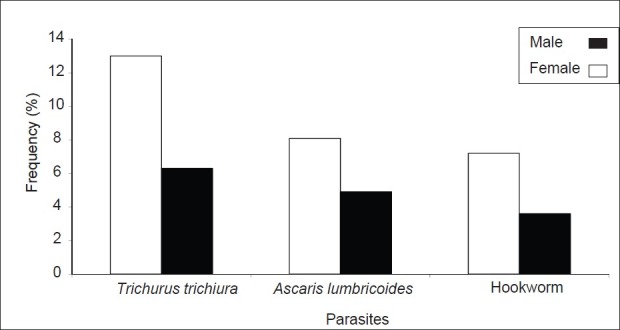

The infection occurred in the earlier ages of (1-10 years) where the prevalence was 4.5%. After, it increased with age and reached the value of 8% in subjects aged (11-20 years). The maximum value was reached in people aged (21-30 years) (11%). Then after, the prevalence decreased in subjects above or equal to 41 years. The cumulative prevalence of the four consecutive age groups (41-50 years, 51-60 years, 61-70 years, and 71-80 years) was 20%. Significant differences were observed between different prevalence of infections (P<0.05). All these data are summarized in Figure 2. Independently of the type of parasite, the prevalence of infection according to the sex is 28.3% for the female and 15.2% for the male [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Variation of the prevalence (%) of nematode infections in the entire population of the study according to age groups

Figure 3.

Variation of the prevalence (%) of nematode infections in the entire population of the study according to sex

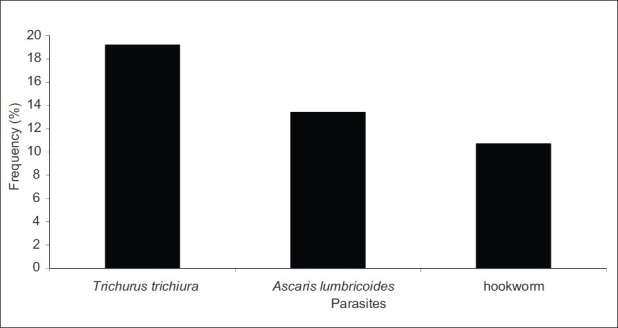

According to the parasite species

The prevalence of each parasitic disease is shown in Figure 4. From this graph it can be seen that trichuriasis is the most prevalent infection (19.2%) followed by ascariasis (13.4%) and ancylostomiasis with the prevalence of 10.7%. A significant difference was observed between the prevalence of infections of trichuriasis and ancylostomiasis (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Variation of the prevalence (%) of each parasite in the entire population of the study

Parasitic combination

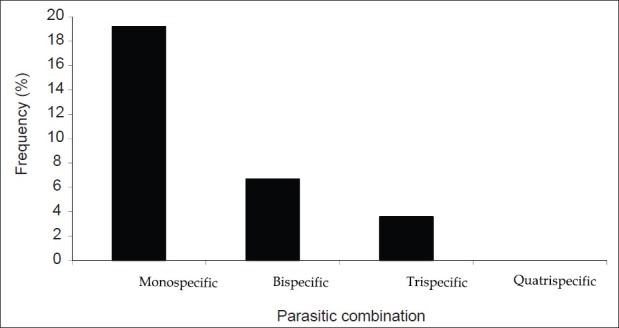

The prevalence of infection by the type of parasitic combination is 19.2% for monospecific parasitism, 6.7%, 3.6%, and 0% for bi-, tri-, and quatri-specific parasitism [Figure 5]. Significant differences were observed between the prevalence of the different parasitic associations (P<0.05). The associations involving two types of parasites species identified in the present study are A. lumbricoides-T. trichiura (2.7%), hookworm-T. trichiura (2.2%), and A. lumbricoides-hookworm (1.8%). For the tri-specific association, we registered A. lumbricoides, hookworm, and T. trichiura in eight cases (3.6%).

Figure 5.

Variation of the prevalence (%) of the type of parasitic combination in the entire population of the study

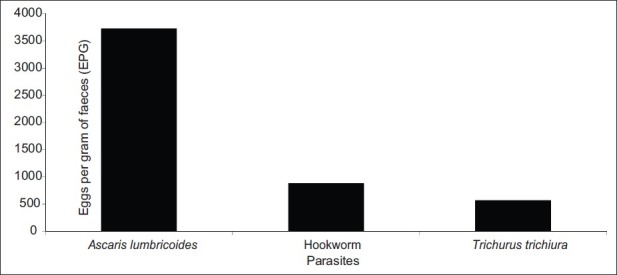

Parasitic burden

Figure 6 illustrated that A. lumbricoides (3722±672) was the intestinal parasite identified which showed the highest parasitic mean intensity in terms of eggs per gram (EPG) of feces followed by hookworm (875±462) and T. trichiura (563± 282). The differences between these parasitic intensity values are statistically significant (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Variation of the parasitic burden in the entire population of the study.

DISCUSSION

The main focus of the present study was to determine the prevalence and intensity of STH and the parasitic intensity in terms of EPG of the persons visiting the centre of phytomedicine for health issues. Results obtained in this work will help to develop measures that could limit the spread of these infections. No specific techniques were used for the detection of pinworm, Strongyloides spp, Schistosoma spp, and Taenia spp. It was noticed that 43.5% of the studied populations were infected by one or several intestinal nematodes. This high prevalence would stimulate more efforts to fight against peril fecal and intestinal worms. The prevalence obtained (43.5%) was higher as that of Menan et al.,[4] who registered a prevalence of 36% in Ivory-Coast and also to that obtained (33.3%) in the same country.[10] Conversely, this prevalence was close to the observations made by Alonzo et al.,[11] who registered a prevalence of 51.6% in Benin and lower to that obtained in Bawa and Nloh, two rural Cameroonian villages.[12] In the present study, we noticed that the prevalence increases with age. Similar observations were made by Menan et al.[4] and Faye et al.,[13] where children aged from 12 to 13 years and 10 to 14 years were more infected with prevalences of 45.5% and 40% respectively than those aged from 6 to 7 years and 0 to 4 years with 33.2% and 28%, respectively. We noticed elsewhere that the prevalence of each nematode identified, differed with the sex of the subjects and the Chi-square test showed a significant difference (P<0.05). In fact, the implication of women in farm work, domestic activities, and in the care of children expose them than other persons (men) to the risk of infection.[14] Trichuriasis was the most prevalent infection. A similar observation was made in urban areas in Abidjan (23.4%), Congo (54.56%), and in ten regions of Cameroon.[4,15,16] This infection was the second in surveys conducted both in Nigeria and Taikkyi.[17,18] Thus, trichuriasis is an urban area infection in tropical and sub-tropical zones.[19] Conversely, studies conducted in Taikkyi township and Nigeria show that ascariasis was the common infection. The prevalence of this disease observed in this study (13.4%) is closer to that obtained in Abidjan (16.5%).[4] Also, these authors registered a high prevalence (50%) of this disease in Gabon. The prevalence of ascariasis varied in inter-tropical zones in Africa. People thought that it is most common in a rain forest region which helps the dissemination of parasitic eggs. The relatively high prevalence of trichuriasis and ascariasis could be also due to the fact that people rear pigs nearer their houses. Secondly, the waste products of their latrine are rejected particularly in the rainy season into the main stream of the Dschang town. Also, this water is used to cultivate vegetables in many parts of the town. Since Trichuris and Ascaris have a similarity in their transmission, their infections may be caused by the uncontrolled defecation of children which is responsible for soil contamination. The prevalence of ancylostomiasis (10.7%) is higher to that reported by Nozais et al.[20] and Thein-Hlains et al.[17] (1.4%). In contrast, this value was low compared to that obtained (84.5%) in Nigeria.[17] This frequency could be due to high humidity conditions of the soil and temperature in tropical areas, which favor the development of the parasite up to infective stage and, on the other hand, to peril fecal and the farm activities done by the population of this region. Given the relatively high prevalence of A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura and the similarity of their transmission routes it is not surprising to find that the association involving A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura was the most prevalent while the one involving A. lumbricoides and hookworm tend to be weak. The same findings were reported in Nigeria.[17] The mean parasitic intensity for each nematode obtained in this work was lower to that obtained in Nigeria but, in any case, it reflected the power of egg output of the different parasites. In fact, Ascaris has a higher egg output (200.000 egg per day), hookworm less (6000 egg/day) and Trichuris lesser (2000 egg per day) as reported.[21] Results obtained in this study show that in spite of the increase in the living standards of the population, the campaign of mass deworming and hygiene done in Dschang, intestinal nematode infections remains a public health issue. We think that it is necessary to promote measures that could help to reduce and to control the extent of intestinal nematodes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express their sincere thanks to all participants and to the personnel of the Centre of Phytomedicine of the ALANGO Foundation for their technical support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yajima AF, Gabrielli AF, Montresor A, Engels D. Moderate and high endemicity of schistosomiasis is a predictor of the endemicity of soil-transmitted helminthiasis: A systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montelmans J. Some economic aspects with respect to veterinary parasitology. Tropicultura. 1986;4:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotez PJ, Zheng F, Long-qi X, Ming-gang C, Shu-hua X, Shu-xian L, et al. Emerging and reemerging helminthiasis and public health of China. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:303–10. doi: 10.3201/eid0303.970306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menan EH, Nebavi NG, Adjetey TA, Assavo NN, Kiki-Barro, Kone M. Intestinales helminthiasis profil in school age children in Abidjan town. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.pathexo.fr/pdt/articles-bull/1997 .

- 5.Belizario VY, Totanesa FI, de Leon WU, Lumampao YF, Ciro RN. Soil-transmitted helminth and other intestinal parasitic infections among school children in indigenous people communities in Davao del Norte, Philippines. Acta Trop. 2011;120(Suppl 1):12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj SM, Sein KT, Anuar AK, Mustaffa BE. Effect of intestinal helminthiasis on school attendance by early primary schoolchildren. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:131–2. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thienpont D, Rochette F, Vanparij OF. Diagnosis of verminosis by coprological examinations. Beerse, Belgium: Janssen Research Foundation; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Euzeby J. Book 1 generality. antemortem diagnostic. Edition technical information of veterinian services. Paris, France: ITSV; 1981. Experimental Diagnostic of animals helminthosis (domesticated animals, laboratory animals, Primates). Practical of veterinary helminthology; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soulsby EJF. Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of domesticated animals. 7th ed. London, United kingdom: Bailliere Tindall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarpaga I. Results of a survey in the rural zone. Thesis of pharmacology. Dakar, Senegal: University of Dakar; 1992. Contribution to the study of the prevalence of intestinal parasitosis in the River Senegal basin. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonzo E, Alonzo V, Forino D, Ioli A. Parasitological research conducted between 1982 and 1991 in a sample of Zinvie (Benin) residents. Med Trop (Mars) 1993;53:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson DJ, Richardson KR, Callahan KD, Gross J, Tsekeng P, Dondji B, et al. Geoheminth infection in rural Cameroonian villages. Comp Parasitol. 2011;78:161–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faye O, N’Dir O, Gay O, Dieng Y, Dieng T, Bah IB, et al. Intestinal parasitosis in the river Senegal basin of. Results of a survey in a rural zone Black Africa Medicine. Med Afr Noire. 1998;45:491–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haswell-Elkins M, Elkins D, Anderson RM. The influence of individual, social group and household factors on the distribution of Ascaris lumbricoïdes within a community and implications for control strategies. Parasitology. 1989;98:125–34. doi: 10.1017/s003118200005976x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atanda HL, Bon JC, Rodier, Kuakuvi N, Porte J, Brunengo P. Intestinal nematodosis Profil in children in congo urban zone. Med Afr. 1981;1:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratard RC, Kouemeni LE, Ekani Bessala MM, Ndamkou CN, Sama MT, Cline BL. Ascariasis and trichuriasis in Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:84–8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thein-Hlaing, Thane-Toe, Than-Saw, Myat-Lay-Kyin, Myint-Lwin A controlled chemotherapeutic intervention trial on the relationship between Ascaris lumbroicoides infection and malnutrition in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:523–8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90242-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holland CV, Asaolu SO, Crompton DW, Stoddart RC, Macdonald R, Torimiro SE. The epidemiology of Ascaris lumbricoides and other soil-transmitted helminths in primary school children from Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Parasitology. 1989;99:275–85. doi: 10.1017/s003118200005873x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oduntan SO. The health of Nigerian children of school age (6-15 years). II. Parasitic and infective conditions, the special senses, physical abnormalities. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1974;68:145–56. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1974.11686933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozais JP, Dunand J, Le Brigant S. Distributions of Ascaris lumbricoides, Necator americanus and Trichuris trichiura in 6 villages of Ivory Coast. Méd Trop (Mars) 1979;39:315–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larivière M, Beauvais B, Derouin F, Traré F. C. H. U. Paris Lariboisière. St Louis: Ellipses; 1987. Medical parasitology; p. 236. [Google Scholar]