Abstract

Exposure to a hypoxic challenge increases ventilation in wild-type (WT) mice that diminish during the challenge (roll-off) whereas return to room air causes an increase in ventilation (short-term facilitation, STF). Since plasma and tissue levels of ventilatory excitant S-nitrosothiols such as S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) increase during hypoxia, this study examined whether (1) the initial increase in ventilation is due to generation of GSNO, (2) roll-off is due to increased activity of the GSNO degrading enzyme, GSNO reductase (GSNOR), and (3) STF is limited by GSNOR activity. Initial ventilatory responses to hypoxic challenge (10% O2, 90% N2) were similar in WT, GSNO+/− and GSNO−/− mice. These responses diminished markedly during hypoxic challenge in WT mice whereas there was minimal roll-off in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. Finally, STF was greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than WT mice (especially females). This study suggests that GSNOR degradation of GSNO is a vital step in the expression of ventilatory roll-off and that GSNOR suppresses STF.

Keywords: hypoxia, ventilatory responses, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase, S-nitrosothiols, mice

1. Introduction

Exposure to a hypoxic challenge activates carotid body chemoafferents which send signals into the brainstem in order to increase minute ventilation (Lahiri et al., 2006; Teppema and Dahan, 2010). The hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) diminishes during exposure to an acute hypoxic challenge. This ventilatory "roll-off" involves changes in neuronal activity within the NTS (Gozal et al., 2000a) and direct depressive effects of hypoxia on central neurons regulating respiratory drive (Martin-Body, 1988). The neurochemical processes in the NTS that underlie the HVR and roll-off has received substantial attention (Bonham, 1995; Burton and Kazemi, 2000; Gozal et al., 2000a). HVR is initiated by activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors (NMDARs) with the ensuing increases in intracellular Ca2+ driving increases in neuronal nitric oxide (NO) synthase (nNOS) activity, as well as phospholipase C, protein kinase C and tyrosine kinase phosphorylation cascades (Gozal et al., 1996; Gozal et al., 2000a). The multi-factorial NTS mechanisms generating roll-off include progressive increases in platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB)-mediated activation of PDGF-β receptors (PDGFR-βs), which diminish NMDAR activity and down-stream signaling cascades (Gozal et al., 2000a,b).

Activation of nNOS in the carotid bodies (Haxhiu et al., 1995; Gozal et al., 1996a) and brainstem (Torres et al., 1997) plays a key role in initiating HVR. The nNOS-mediated generation of nitric oxide (NO), could not mediate this response because NO inhibits hypoxic chemotransduction in the brainstem (Vitagliano et al., 1996) and carotid bodies (Lahiri et al., 2006; Yamomoto et al., 2006). However, nNOS also generates S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) such as S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), S-nitrosocysteinylglycine (SNO-CG) and S-nitrosocysteine (SNO-CYS) in tissues including the brain (Do et al., 1996; Kluge et al., 1997; Salt et al., 2000; Hogg et al., 2002; Foster et al., 2003; Gaston et al., 2006). These SNOs increase minute ventilation upon injection into the NTS of conscious rats (Lipton et al., 2001). Moreover, hypoxia generates SNOs in a variety of cells and blood (Gaston et al., 2003; Allen et al., 2009; Ho et al., 2012) and increases S-nitrosylation of functional proteins (Hogg et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2008; Wiktorowicz et al., 2011), including NMDARs (Takahashi et al., 2007). However, exogenous SNO-L-CYS or activation of endogenous S-nitrosylation cascades restore activated NMDARs to normal activity (Choi et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007) thereby promoting ventilatory roll-off (Gozal et al., 2000a). This inhibitory effect would be counter-balanced by the ability of GSNO to directly activate NMDARs via S-nitrosylation-independent events (Hermann et al., 2000; Chin et al., 2006) and by γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT)-mediated conversion of GSNO to SNO-CG, which also potentiates the neuronal excitant effects of NMDA (Salt et al., 2000).

The cessation of a hypoxia challenge can result in ventilatory parameters increasing or remaining above baseline for a substantial time. This short-term facilitation (STF), which occurs in humans (Dahan et al., 1995), rats (Moss et al., 2006), and mice (Kline and Prabhakar, 2001; Kline et al., 2002), is due to a central neural mechanism that drives ventilation independently of peripheral or central chemoreceptor inputs (Millhorn et al., 1980). Although little is known about the underlying neurochemical processes, STF is markedly diminished in nNOS knock-out mice (Kline and Prabhakar, 2001; Kline et al., 2002), suggesting a role for excitatory SNOs rather than NO per se. It is therefore possible that the generation of SNOs and S-nitrosylation events in the brainstem and carotid bodies play crucial roles on the expression of HVR and STF.

GSNO regulates the activities of cell proteins by S-nitrosylation of key cysteine residues (Hess et al., 2005; Foster et al., 2009). GSNO levels are decreased by the thioredoxin reductase-thioredoxin system (Stoyanovsky et al., 2005), γ-GT (Hogg et al., 1997; Salt et al., 2000), and by alcohol dehydrogenase III, which catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of GSNO to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), and is therefore known as GSNO reductase (GSNOR) (Jensen et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2001a; Hedberg et al., 2003; Staab et al., 2008). GSNOR plays a key role in the degradation of tissue GSNO and the abundance of S-nitrosylated proteins in transnitrosation equilibrium with GSNO (Liu et al., 2004; Que et al., 2005; Lima et al., 2009). GSNOR regulates GSNO levels in the lungs (Que et al., 2005), vasculature (Liu et al., 2004) and heart (Lima et al., 2009) and is widely distributed in the brain (Beisswenger et al., 1985; Giri et al., 1989; Galter et al., 2003). However, to our knowledge, the presence of GSNOR in the carotid bodies or brainstem sites involved in ventilatory control has not been established. NADH is critical for GSNOR activity. The cell ratio of free NAD+/NADH is typically high (Williamson et al., 1967; Zhang et al., 2002) and does not favor reductive pathways such as GSNO degradation by GSNOR. However, exposure to a hypoxic challenge greatly increases (1) the ratio NADH/NAD+ in rabbit carotid body primary glomus cells (Duchen and Biscoe, 1992a,b), (2) NADH levels in neurons in the brainstem respiratory center of mice (Mironov and Richter, 2001), and (3) pyridine nucleotide (most-likely NADH) levels in rat diaphragm (Paddle, 1985). Thus hypoxia engenders NADH-dependent increases in the activity of GSNOR in the brainstem (Giri et al., 1989; Galter et al., 2003).

The concepts underlying the present study are that (1) the generation of GSNO initiates HVR but as time progresses the NADH-dependent increase in GSNOR activity and enhanced degradation of GSNO contribute to roll-off, (2) increased GSNOR activity may contribute to attenuating STF during the early stages of return to room air when NADH levels and GSNOR activity gradually return to pre-hypoxia levels, and (3) diminished expression and/or activity of GSNOR may abolish hypoxic roll-off and facilitate STF in males and females and abolish the gender differences in these responses. To address these concepts, this study determined the ventilatory responses during exposure to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2 for 15 min) and upon return to room air in conscious male and female wild-type (WT) C57 black 6 (C57BL6) mice and in GSNOR deficient (heterozygous, GSNOR+/−) and GSNO null (knock-out, GSNOR−/−) mice. This study, which is the first pertaining to HVR, roll off and STF in GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice, provides compelling evidence for key rolls of GSNO and GSNOR in ventilatory responses.

2. Methods

2.1. Mice

All studies were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 80-23) revised in 1996. The protocols were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult male and female C57BL6, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (n=70) were obtained from a breeding colony maintained at the University of Virginia. The status of the menstrual cycle was not accounted for because of reasons explained in our companion manuscript (see Palmer et al., 2012). Genotypes of the mice used in this study were identified by real time PCR (Liu et al., 2004). Functional confirmation of genotype was determined by GSNOR activity assay (Brown-Steinke et al., 2010) using brainstem homogenates.

2.2. Ventilatory Parameters

Ventilatory parameters were continuously recorded in four conscious unrestrained mice at a time using a whole-body chamber plethysmography system (PLY 3223; BUXCO Incorporated, Wilmington, NC, USA) described previously (Kanbar et al., 2010). Parameters were frequency of breathing (fR); tidal volume (VT); ventilation (V̇); inspiratory time (TI); expiratory time (TE); VT/TI, an index of respiratory drive (Moss et al., 2006); peak inspiratory flow (PIF), and peak expiratory flow (PEF). The provided software constantly corrected digitized values for changes in chamber temperature and humidity. A rejection algorithm was included in the breath-by-breath analysis to exclude episodes of nasal breathing. Since there were no differences in body weights between the 3 groups of females and between the 3 groups of males (see Table 1), parameters related to lung volumes such as VT are shown without corrections for body weights.

Table 1.

Body weights and ages of female and male mice

| Gender | Parameter | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Number | 16 | 9 | 17 |

| Body Weight, grams | 21.8 ± 0.6 | 20.9 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.4 | |

| Age, days | 102 ± 2 | 83 ± 3*,† | 98 ± 2 | |

| Male | Number | 16 | 7 | 5 |

| Body Weight, grams | 23.2 ± 0.6 | 24.1 ± 0.4 | 23.0 ± 0.5 | |

| Age, days | 84 ± 3 | 89 ± 3 | 100 ± 3*,† |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05, GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice versus WT mice.

2.3. Hypoxia challenge

Mice were placed in the plethysmography chambers and allowed 45–60 min to acclimatize. The data were continuously recorded (i.e., breath by breath) throughout the acclimatization period and subsequent study. After acclimatization, the mice were exposed to a hypoxic challenge of 10% O2, 90% N2 (Gassmann et al., 2009; Gozal et al., 2000b; Teppema and Dahan, 2010) for 15 min after which time they were re-exposed to room air and data recorded for 5 or 15 min.

2.4. Statistics

The recorded data (1 min bins) and derived parameters, VT/TI and Response Area (cumulative % changes from pre-hypoxia values) were taken for statistical analyses. The 1 min bins collected before hypoxic challenge excluded occasional marked deviations from resting due to abrupt movements by the mice. The data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Student's modified t test with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons between means. A value of P < 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Female mice

3.1.1. Body weights, ages and baseline ventilatory parameters

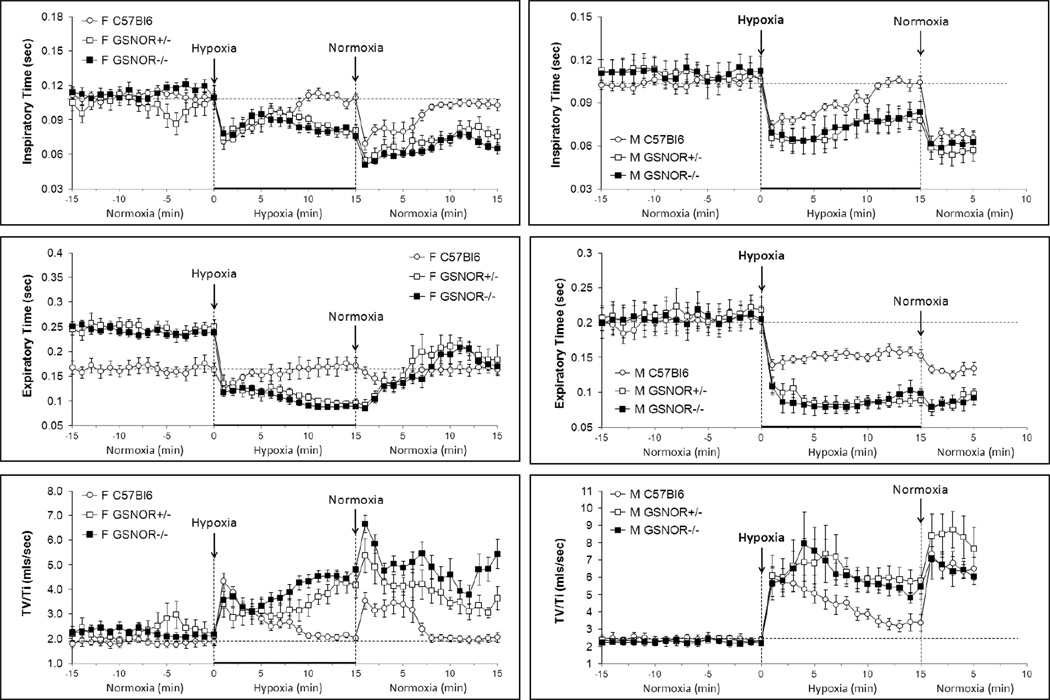

The body weights of female WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were similar to one another (Table 1). The WT and GSNOR−/− mice were similar in age whereas the GSNOR+/− mice were younger. Resting ventilatory parameters recorded before hypoxic challenge are summarized in Figs. 1−4 and Table 2. Resting fR was consistently lower in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice and equivalent between GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (Fig. 1). Resting VT and V̇ were similar in the three groups (Fig. 1). Resting TI was similar in all groups (Fig. 2) whereas resting TE was greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than WT mice and similar between GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (Fig. 2). Resting VT/TI (Fig. 2), PIF and PEF (Fig. 3) were similar in all groups.

Fig. 1.

Changes in frequency of breathing (top panels), tidal volume (middle panels) and ventilation (bottom panels) during exposure to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2 for 15 min) and following return to room-air (normoxia). Left-hand panels: Conscious female C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=9) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=17). Right-hand panels: Conscious male C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=7) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=5).The stippled horizontal lines denote the average resting values immediately before exposure to hypoxia. The data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Table 2.

Ventilatory parameters at key stages of the experiment in FEMALE mice

| Parameter | Stage | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, breaths/min | Pre | 219 ± 8 | 195 ± 7* | 197 ± 6* |

| H1 | 329 ± 14† | 360 ± 52† | 361 ± 24† | |

| H15 | 217 ± 10 | 331 ± 16†,‡ | 388 ± 16†,‡ | |

| N1 | 299 ± 9† | 461 ± 39†,‡ | 480 ± 14†,‡ | |

| N15 | 228 ± 11 | 298 ± 38† | 363 ± 31†,‡ | |

| TV, mls | Pre | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

| H1 | 0.31 ± 0.02† | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | |

| H15 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.04†,‡ | 0.36 ± 0.01†,‡ | |

| N1 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.02†,‡ | 0.34 ± 0.02†,‡ | |

| N15 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.02†,‡ | |

| MV, mls/min | Pre | 45 ± 3 | 45 ± 2 | 47 ± 3 |

| H1 | 102 ± 9† | 86 ± 16† | 94 ± 10† | |

| H15 | 48 ± 3 | 117 ± 18†,‡ | 137 ± 6†,‡ | |

| N1 | 70 ± 4† | 138 ± 20†,‡ | 162 ± 9†,‡ | |

| N15 | 48 ± 5 | 76 ± 13†,‡ | 122 ± 15†,‡,# | |

| Ti, sec | Pre | 0.11 ± 0.003 | 0.10 ± 0.004 | 0.11 ± 0.004 |

| H1 | 0.07 ± 0.002† | 0.07 ± 0.010 | 0.08 ± 0.006† | |

| H15 | 0.11 ± 0.004 | 0.08 ± 0.005†,‡ | 0.08 ± 0.003†,‡ | |

| N1 | 0.07 ± 0.006† | 0.05 ± 0.006† | 0.05 ± 0.005† | |

| N15 | 0.10 ± 0.005 | 0.08 ± 0.007†,‡ | 0.07 ± 0.005†,‡ | |

| Te, sec | Pre | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01* | 0.24 ± 0.01* |

| H1 | 0.12 ± 0.01† | 0.14 ± 0.02† | 0.12 ± 0.01† | |

| H15 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01†,‡ | 0.09 ± 0.01†,‡ | |

| N1 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01†,‡ | 0.08 ± 0.01†,‡ | |

| N15 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.03† | 0.17 ± 0.02† | |

| TV/Ti, mls/sec | Pre | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| H1 | 4.3 ± 0.4† | 3.4 ± 0.5† | 3.6 ± 0.4† | |

| H15 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.5†,‡ | 4.8 ± 0.3†,‡ | |

| N1 | 3.5 ± 0.4† | 5.4 ± 0.7†,‡ | 6.7 ± 0.4†,‡ | |

| N15 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5†,‡ | 5.4 ± 0.6†,‡,# | |

| PIF, mls/sec | Pre | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| H1 | 6.5 ± 0.3† | 5.5 ± 0.9† | 5.7 ± 0.06† | |

| H15 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.8†,‡ | 6.9 ± 0.3†,‡ | |

| N1 | 5.9 ± 0.4† | 9.1 ± 1.1†,‡ | 11.6 ± 0.5†,‡,# | |

| N15 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.4†,‡ | 9.3 ± 0.9†,‡,# | |

| PEF, mls/sec | Pre | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| H1 | 4.9 ± 0.4† | 4.4 ± 0.7† | 4.8 ± 0.5† | |

| H15 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.8†,‡ | 8.1 ± 0.3†,‡ | |

| N1 | 4.0 ± 0.4† | 6.7 ± 0.9†,‡ | 8.4 ± 0.4†,‡ | |

| N15 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.3†,‡ | 6.1 ± 0.7†,‡ |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. H1 and H2 are values at 1 and 15 min time-points during exposure to Hypoxia, respectively. N1 and N2 are values at 1 and 15 min time-points following re-exposure to room air (Normoxia), respectively.

P < 0.05, pre values of GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice versus pre values of C57Bl6 mice.

P < 0.05, significant response.

P < 0.05, GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− response versus C57Bl6 response.

P < 0.05, GSNOR−/− response versus GSNOR+/− response.

Fig. 2.

Changes in Inspiratory time (top panels) and Expiratory Time (middle panels) and Tidal volume/Inspiratory time (VT/TI, index of respiratory drive) (bottom panels) during exposure to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2 for 15 min) and following return to room-air (normoxia). Left-hand panels: Conscious female C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=9) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=17). Right-hand panels: Conscious male C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=7) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=5). The stippled horizontal lines denote the average resting values immediately before exposure to hypoxia. The data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Fig. 3.

Changes in peak inspiratory flow (top panels) and peak expiratory flow (bottom panels) during exposure to hypoxia (10% O2, 90% N2 for 15 min) and following return to room-air (normoxia). Left-hand panels: Conscious female C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=9) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=17). Right-hand panels: Conscious male C57BL6 mice (n=16), GSNOR+/− mice (n=7) and GSNOR−/− mice (n=5). The stippled horizontal lines denote the average resting values immediately before exposure to hypoxia. The data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3.1.2. Effects of hypoxia on ventilatory parameters

Exposure of WT mice to the hypoxic challenge elicited immediate (1) increases in fR, VT and V̇ (Fig. 1, Table 2), (2) decreases in TI and TE (Fig. 2, Table 2), (3) increase in VT/TI (Fig. 2, Table 2), and (4) increases in PIF and PEF (Fig. 3, Table 2). Exposure of GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice to the hypoxic challenge elicited similar initial responses compared to WT mice (Figs 1–3, Table 2) with two exceptions. First, the initial increase in VT was somewhat smaller in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 1, Table 2). Second, although the decreases in TE were greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than WT mice, similar nadir values were reached (Fig. 2, Table 2). In WT mice, the changes in all parameters were not sustained during exposure to the hypoxic challenge and so displayed roll-off (Figs 1–3, Table 2). In contrast, there was minimal roll-off in any tested parameter in GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice. Minimal differences were observed between GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (Figs 1–3, Table 2). As such, the cumulative responses (RC) during exposure to hypoxia were greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice and similar between GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cumulative responses of FEMALE C57Bl6, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice during exposure to hypoxia and subsequent normoxia

| HYPOXIA | NORMOXIA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− |

| Frequency, (breaths/min) × min | +443 ± 64* | +2007 ± 259*,† | +2181 ± 108*,† | +213 ± 53* | +1874 ± 257*,† | +2440 ± 199*,† |

| TV, (mls) × min | +0.56 ± 0.09* | +0.99 ± 0.12*,† | +1.10 ± 0.19*,† | +0.30 ± 0.06 | +0.37 ± 0.14* | +0.61 ± 0.15*,† |

| MV, (mls/min) × min | +261 ± 40* | +800 ± 101*,† | +1012 ± 83*,† | +119 ± 22* | +600 ± 83*,† | +935 ± 130*,†,‡ |

| Ti, (sec) × min | −0.19 ± 0.02* | −0.25 ± 0.02*,† | −0.44 ± 0.05*,† | −0.26 ± 0.03* | −0.42 ± 0.07*,† | −0.62 ± 0.06*,† |

| Te, (sec) × min | −0.10 ± 0.11 | −2.08 ± 0.16*,† | −2.05 ± 0.09*,† | −0.12 ± 0.10 | −1.17 ± 0.13*,† | −1.18 ± 0.13*,† |

| TV/Ti, (mls/sec) × min | +10.3 ± 1.4* | +16.6 ± 1.5*,† | +24.9 ± 3.3*,† | +10.6 ± 2.4* | 20.2 ± 3.6*,† | +36.6 ± 5.7*,† |

| PIF, (mls/sec) × min | +17 ± 3* | +34 ± 4*,† | +41 ± 4*,† | +11 ± 3* | +66 ± 6*,† | +78 ± 8*,† |

| PEF, (mls/sec) × min | +18 ± 2* | +48 ± 9*,† | +52 ± 5*,† | +6 ± 2* | +26 ± 5*,† | +38 ± 7*,† |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05, significant cumulative response.

P < 0.05, GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− versus C57Bl6.

P < 0.05, GSNOR−/− versus GSNOR+/−.

3.1.2. Effects of return to room air on ventilatory parameters

In WT mice, return to room-air resulted in (1) increases in fR, VT and V̇ (Fig. 1, Table 2), (2) decreases in TI and TE (Fig. 2, Table 2), (3) an increase in VT/TI (Fig. 2, Table 2), and (4) an increase in PIF and to a lesser degree an increase in PEF (Fig. 3, Table 2). These responses lasted for about 5–7 min. The responses upon return to room-air were sustained for longer periods of time in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice and most variables had not returned to baseline by 15 min (Figs. 1–3, Table 2), the exceptions being VT and TE in the GSNOR+/− mice (Table 2), which recovered more quickly. Accordingly, RC values during return to room air were greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice for all parameters. Minimal differences were observed between the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (Table 3).

3.2. Male mice

3.2.1. Body weights, ages and baseline ventilatory parameters

The body weights of the male WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were similar to one another (Table 1). The ages of the WT and GSNOR+/− mice were similar whereas the GSNOR−/− mice were older. Resting ventilatory parameters prior to hypoxic challenge are summarized in Figs 1–3 and Table 4. There were no between-group differences in any ventilatory parameter.

Table 4.

Ventilatory parameters at key stages of the experiment in MALE mice

| Parameter | Stage | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, breaths/min | Pre | 221 ± 10 | 206 ± 11 | 205 ± 13 |

| H1 | 314 ± 16* | 424 ± 24*,† | 405 ± 33*,† | |

| H15 | 245 ± 11 | 361 ± 9*,† | 348 ± 21*,† | |

| N1 | 361 ± 21* | 452 ± 38*,† | 463 ± 16*,† | |

| N5 | 351 ± 21* | 411 ± 30*,† | 428 ± 41*,† | |

| TV, mls | Pre | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.02 |

| H1 | 0.44 ± 0.04* | 0.37 ± 0.04* | 0.36 ± 0.02* | |

| H15 | 0.34 ± 0.04* | 0.43 ± 0.03*,† | 0.44 ± 0.03*,† | |

| N1 | 0.45 ± 0.03* | 0.44 ± 0.03* | 0.42 ± 0.03* | |

| N5 | 0.42 ± 0.03* | 0.39 ± 0.05* | 0.37 ± 0.02* | |

| MV, mls/min | Pre | 56 ± 6 | 52 ± 4 | 54 ± 3 |

| H1 | 137 ± 13* | 159 ± 21* | 147 ± 15* | |

| H15 | 85 ± 12* | 157 ± 15*,† | 152 ± 14*,† | |

| N1 | 159 ± 11* | 199 ± 26* | 195 ± 25* | |

| N5 | 144 ± 10* | 160 ± 26* | 155 ± 14* | |

| Ti, sec | Pre | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| H1 | 0.07 ± 0.01* | 0.07 ± 0.01* | 0.07 ± 0.01* | |

| H15 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01* | 0.08 ± 0.01* | |

| N1 | 0.06 ± 0.01* | 0.06 ± 0.01* | 0.06 ± 0.01* | |

| N5 | 0.07 ± 0.01* | 0.06 ± 0.01* | 0.06 ± 0.01* | |

| Te, sec | Pre | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| H1 | 0.14 ± 0.01* | 0.11 ± 0.01* | 0.11 ± 0.01* | |

| H15 | 0.15 ± 0.01* | 0.09 ± 0.01*,† | 0.10 ± 0.01*,† | |

| N1 | 0.13 ± 0.01* | 0.08 ± 0.01*,† | 0.08 ± 0.01*,† | |

| N5 | 0.13 ± 0.01* | 0.10 ± 0.01* | 0.09 ± 0.01*,† | |

| TV/Ti, mls/sec | Pre | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

| H1 | 6.0 ± 0.5* | 6.1 ± 1.2* | 5.7 ± 1.0* | |

| H15 | 3.4 ± 0.3* | 5.8 ± 0.8*,† | 5.5 ± 0.7*,† | |

| N1 | 7.4 ± 0.5* | 8.4 ± 1.8* | 7.1 ± 1.2* | |

| N5 | 6.5 ± 0.7* | 7.7 ± 1.8* | 6.1 ± 0.5* | |

| PIF, mls/sec | Pre | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| H1 | 8.5 ± 0.5* | 9.6 ± 0.7* | 9.9 1.5* | |

| H15 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.6*,† | 7.6 ± 1.5* | |

| N1 | 10.3 ± 0.5* | 12.1 ± 1.6* | 11.1 ± 1.1* | |

| N5 | 8.7 ± 0.6* | 9.1 ± 1.3* | 10.2 ± 1.1* | |

| PEF, mls/sec | Pre | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.4 |

| H1 | 6.0 ± 0.5* | 8.3 ± 0.6*,† | 7.2 ± 0.5* | |

| H15 | 5.1 ± 0.4* | 9.9 ± 0.6*,† | 8.3 ± 0.6*,† | |

| N1 | 8.1 ± 0.5* | 12.5 ± 1.4*,† | 10.9 ± 1.3* | |

| N5 | 6.1 ± 0.4* | 8.8 ± 1.1*,† | 8.4 ± 0.7*,† |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. H1 and H2 are values at 1 and 15 min time-points during exposure to hypoxia, respectively. N1 and N2 are values at 1 and 5 min time-points following re-exposure to room air (normoxia), respectively.

P < 0.05, significant response.

P < 0.05, GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− response versus C57Bl6 response.

3.2.2. Effects of hypoxia on ventilatory parameters

As in female WT mice, exposure of male WT mice to hypoxia elicited immediate (1) increases in fR, VT and V̇ (Fig. 1, Table 4), (2) decreases in TI and TE (Fig. 2, Table 4), (3) increase in VT/TI (Fig. 3, Table 4), and (4) increases in PIF and PEF (Fig. 3, Table 4). Exposure of male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice to hypoxia elicited greater initial increases in fR than in male WT mice but lesser increases in VT such that the increases in V̇ were similar in the three groups (Fig 1, Table 4). The greater initial increases in fR in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were associated with greater decreases in TE than TI (Fig. 2, Table 4). The initial increases in VT/TI (Fig. 2, Table 4), PIF and PEF (Fig. 3, Table 4) were similar in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. In WT mice, roll-off during hypoxia was evident in most variables but was less pronounced for TE (Fig. 2, Table 4) and PEF (Fig. 3, Table 4). As with female mice, there was minimal roll-off in any measured parameter in male GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice (Figs 1–3, Table 4). As such, the RC values during exposure to hypoxia were greater in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in male WT mice. No differences between GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were observed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cumulative responses of MALE mice during exposure to hypoxia and subsequent normoxia

| HYPOXIA | NORMOXIA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− | WT | GSNOR+/− | GSNOR−/− |

| Frequency, (breaths/min) × min | +429 ± 27* | +2860 ± 121*,† | +2779 ± 197*,† | +637 ± 90* | +1172 ± 139*,† | +1230 ± 158*,† |

| TV, (mls) × min | +0.91 ± 0.08* | +2.43 ± 0.25*,† | +2.21 ± 0.20*,† | +0.93 ± 0.13* | +0.82 ± 0.14* | +0.68 ± 0.18*,† |

| MV, (mls/min) × min | +385 ± 33* | +1694 ± 163*,† | +1608 ± 114*,† | +472 ± 38* | +662 ± 75*,† | +594 ± 42*,† |

| Ti, (sec) × min | −0.13 ±0.02* | −0.59 ± 0.03*,† | −0.56 ± 0.07*,† | −0.19 ± 0.02* | −0.27 ± 0.02*,† | −0.25 ± 0.05*,† |

| Te, (sec) × min | −0.27 ± 0.06* | −1.82 ± 0.18*,† | −1.77 ± 0.19*,† | −0.35 ± 0.07* | −0.62 ± 0.06*,† | −0.60 ± 0.07*,† |

| TV/Ti, (mls/sec) × min | +15.6 ± 1.4* | +60.3 ± 13.2*,† | +54.1 ± 10.2*,† | +21.4 ± 2.1* | +30.0 ± 5.1* | +20.3 ± 3.1* |

| PIF, (mls/sec) × min | +17 ± 1* | +61 ± 6*,† | +66 ± 14*,† | +22.0 ± 3.3* | +29.0 ± 3.6* | +31.2 ± 4.5* |

| PEF, (mls/sec) × min | +11 ± 2* | +104 ± 9*,† | +93 ± 6*,† | +15.6 ± 1.5* | +38.5 ± 4.1*,† | +31.7 ± 3.4*,† |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05, significant cumulative response.

P < 0.05, GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− versus C57Bl6.

3.2.2. Effects of return to room air on ventilatory parameters

In WT mice, return to room-air elicited initial increases in fR, VT, and V̇ (Fig. 1, Table 4), decreases in TI and TE (Fig. 2, Table 4), and increase in VT/TI in (Fig. 2, Table 4), PIF and PEF (Fig. 3, Table 4). All responses were still evident after 5 min. Similar responses were observed in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. Differences in actual size of the responses in comparison to WT mice were a reflection of the differences in starting values at the end of the hypoxic challenge (Figs. 1–3, Table 4). RC values upon return to room-air (Table 5) were as follows; fR, greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice because of the differences in starting values; VT, similar in all three groups; V̇, slightly higher in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice; TI and TE, greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice; VT/TI and PIF, similar in all three groups; PEF, greater in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than in WT mice.

3.3. Comparison of ventilatory responses in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice

The fR, VT, TI, TE and VT/TI responses in female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were similar to one another during and after hypoxic challenge. V̇ responses of female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were similar during hypoxia whereas post-hypoxia responses were greater in GSNO−/− than GSNO+/− mice. PIF responses were similar in female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice during hypoxia (except for +7 to +12 min in which values were higher in GSNO−/− than GSNO+/− mice) and upon return to room-air. PEF responses were similar in female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice during and after hypoxic challenge (except for the later stages when values were higher in GSNOR−/− mice). The responses in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were indistinguishable from one another during and after exposure to hypoxia.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

This study demonstrates that whereas the ventilatory responses during and after H-H challenge were similar in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice, the responses during and after hypoxic challenge were markedly different in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice as compared to WT mice. Although the initial responses to hypoxia were in general similar in the three groups, roll-off was smaller in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than WT mice and the responses that occurred upon return to room-air were markedly exaggerated in the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice.

4.2. Age and body weight considerations

The body weights of three groups of female mice and three groups of male mice were similar to one another. The female WT and GSNOR−/− mice were of similar age whereas the GSNOR+/− mice were younger. The male WT and GSNOR+/− mice were of similar age whereas the GSNOR−/− mice were older. Since the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice had similar ventilatory responses, it is evident that body weights and ages are not factors in the different responses of these mice compared to WT mice. Moreover, exposure to the hypoxic challenge and return to room-air resulted in similar changes in body temperature in male WT and GSNOR−/− mice (Palmer et al., unpublished observations) suggesting that metabolic factors do not underlie the differences in ventilatory responses of WT and GSNOR−/− (and probably GSNOR+/−) mice.

4.3. Resting ventilatory parameters in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice

Several resting ventilatory parameters were different in female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice as compared to female WT mice. More specifically, resting fR were lower in the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than the WT mice whereas resting VT tended to be higher in the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice such that V̇ was similar in each group. With respect to respiratory timing, TI was equivalent in the three groups whereas TE was of much longer duration in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. Accordingly, the enhanced duration of passive expiration rather than active inspiration underlay the diminished fR in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. The findings that resting VT/TI, PIF and PEF were similar in female WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice suggests that GSNOR has little tonic affect on central respiratory drive (VT/TI) or the ability to reach maximal inspiratory or expiratory flows. Since expiration in mammals including mice is due to relaxation of diaphragmatic and external intercostal muscles actively recruited during the inspiratory cycle (Detroyer et al., 2005), it is feasible that GSNO promotes relaxation and that this mechanism is under the control of GSNOR. Unlike females, resting ventilatory parameters were similar in male WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. Accordingly, it appears that the GSNOR-dependent processes regulating fR and expiratory duration are gender-dependent.

4.4. Ventilatory responses to hypoxic challenge in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice

The initial ventilatory responses (+1 to + 3 min) elicited by the hypoxic challenge were similar in female WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice (except for somewhat smaller increases in VT in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice). In contrast, several of the ventilatory responses during hypoxic challenge in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were different to those of the male WT mice. The male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice displayed a substantially greater increase in fR than the male WT mice. Since the enhanced fR responses of the GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were accompanied by relatively smaller increases in VT than the WT mice, the initial increases in V̇ were similar in all three groups. The enhanced increases in fR elicited by hypoxic challenge in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice were associated with exaggerated decreases in TE rather than TI. Finally, the initial increases in VT/TI and PIF were similar in all three groups of male mice whereas the increases in PEF were greater in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than male WT mice. It therefore appears that GSNOR plays a key role in the expression of the hypoxia-driven increases in fR in male mice. Whether the exaggerated hypoxia-induced increases in fR in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice are due to greater abundance and activity of GSNO in the blood, carotid bodies and/or brain remain to be determined.

The greater decreases in TE than TI in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice coupled with the more pronounced increases in PEF than PIF raises the possibility that GSNOR plays a key role in regulating the recruitment of internal intercostal and diaphragmatic muscles responsible for hypoxia-induced active expiration (Detroyer et al., 2005) or the efficiency of peripheral neuromuscular processes. However, GSNO diminishes Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus and inhibits excitation-contraction coupling processes in skeletal muscle via S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation processes (Nogueira et al., 2009; Spencer et al., 2009; Dutka et al., 2011). As such, the loss of GSNOR in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice would enhance GSNO concentrations and in theory, diminish the rate and force of contraction of the muscles driving active expiratory ventilation. However, GSNO, SNO-L-CYS and S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP), activate skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors, intracellular Ca2+ release and skeletal muscle contraction via S-nitrosylation events (Suko et al., 1999; Dulhunty et al., 2000; Hart and Dulhunty, 2000). Our in vivo data suggest that relatively greater increases in intracellular SNO formation during hypoxia in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice promote contraction of muscles involved in active expiration. This is supported by evidence that SNAP facilitates neurotransmission in rat diaphragm muscle (Queiroz and Alves-Do-Prado, 2001).

4.5. Ventilatory roll-off in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice

The ventilatory responses of female and male WT mice displayed substantial ventilatory roll-off during the hypoxic challenge. In contrast, roll-off was minimal in female and male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. These findings support the concepts that generation of GSNO in the NTS drives minute ventilation (Lipton et al., 2001), and that an increase in GSNOR activity and enhanced degradation of GSNO is a vital process in roll-off. The early phase of the HVR is critically dependent on NMDAR activation in the NTS (see Gozal et al., 2000a). Accordingly, the ability of SNOs, and in particular, SNO-L-CYS, to S-nitrosylate NMDARs in WT mice would restore normal receptor activity (Choi et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007), promoting roll-off. The inhibitory influence of S-nitrosylation on NMDARs would be counter-balanced by the direct (S-nitrosylation-independent) activation of NMDARs (Hermann et al., 2000; Chin et al., 2006). Thus, an increase in GSNOR activity would promote roll-off by diminishing GSNO levels, allowing SNO-L-CYS-induced S-nitrosylation of NMDARs to dominate the effects of GSNO. As such, hypoxia-induced increase in the S-nitrosylation status of NMDARs in GSNOR+/− or GSNOR−/− mice would be over-ridden by the increased levels of GSNO promoting NMDAR activity.

Intracellular NADH generated during hypoxia elevates cytoplasmic Ca2+ via activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors on intracellular Ca2+ stores (Kaplin et al., 1996). This increase in Ca2+ would activate nNOS-mediated generation of SNOs. The resultant S-nitrosylation events would (1) increase cell Ca2+ entry by activation of store-operated Ca2+-channels, the activation and maintenance of which requires IP3-receptors (Ma et al., 1999), and (2) induce Ca2+-release from IP3 receptor-sensitive stores (Pan et al., 2008). It is likely that this Ca2+ has positive effects on ventilatory control neurons in the brainstem (Teppema and Dahan, 2010) and carotid bodies (Lahiri et al., 2006), and promotes chest-wall and diaphragmatic muscle contractions (Ma et al., 1999). Gozal et al (2000b) reported that PDGF-BB release and PDGFR-β activation in the NTS are key components of roll-off. They found that (1) microinjection of PDGF-BB into the NTS attenuated the early HVR in conscious rats, (2) PDGFR-β tyrosine phosphorylation in the NTS correlated temporally with roll-off, and (3) PDGFR-β+/− mice had similar initial peak HVR to those of wild-type mice whereas roll-off was markedly reduced (Gozal et al., 2000b). Binding of PDGF to its receptors induces dimerization of receptor α-chains (PDGFR-α) and β-chains (PDGFR-β) is a pre-requisite for receptor autophosphorylation and receptor tyrosine kinase activity and subsequent signal transduction (Claesson-Welsh, 1994). The level of tyrosine phosphorylation is regulated by tyrosine kinases and phosphatases (Hunter, 1995). Callsen et al (1999) found that GSNO and SNAP elicited ligand-independent phosphorylation of PDGFRs via cGMP-independent (presumably S-nitrosylation-mediated) inhibition of PDGFR tyrosine phosphatases. Accordingly, SNO-mediated S-nitrosylation events would promote PDGFR-β activity, inhibition of NMDAR activity, and therefore roll-off.

The brain contains GSNO (Do et al., 1996; Kluge et al., 1997) and SNO-CG (Salt et al., 2000). Hypoxia-induced, NOS generation of GSNO presumably occurs in the cytoplasm of GSNOR-containing cells to regulate protein S-nitrosylation and protein trafficking (Iwakiri et al., 2006; Qian et al., 2010). However, it is feasible that GSNO or SNO-CG are released from nerve terminals in the brain (Do et al., 1996; Kluge et al., 1997) including chemoafferents terminating in the commissural NTS, the vast majority of which stain for NADH diaphorase, a marker for NOS (Ruggiero et al., 1996). Upon release, GSNO could activate NTS cells via (1) direct activation of NMDARs (Choi et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007), (2) sequential conversion to SNO-GC (Salt et al., 2000; Lipton et al., 2001) to SNO-L-CYS via a dipeptidase (Lipton et al., 2001), with subsequent cell entry of SNO-L-CYS via the L-aromatic amino acid uptake system (Li and Wharton, 2007), or (3) activation of specific membrane receptors. With respect to such receptors, Janáky et al (2000) provided evidence that reduced glutathione (GSH) acts as an excitatory neurotransmitter at unique plasma membrane receptors. In these receptors, the cysteinyl moiety is crucial for [3H]GSH binding and oxidation or alkylation of the cysteine thiol group of GSH reduces binding affinity. Moreover, GSNO was a potent displacer of GSH binding (Janáky et al., 2000). The possibility that GSNO is an excitatory direct/allosteric activator of these putative GSH receptors would be an important advance in understanding the signaling mechanisms of SNOs. Specific [3H]GSNO binding sites, which are not displaceable by glutamate receptor ligands, exist on synaptic plasma membranes (Taguchi et al., 1995; Talman et al., 1997). Whether these sites are novel “receptors” that also recognizes SNO-L-CYS (Talman et al., 1997) or the GSH receptor sites described by Janáky et al (2000) remain to be determined.

Hypoxia activates NOS activity in brain (Gutsaeva et al., 2008; Mishra et al., 2010), sensory nerves (Henrich et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2003), carotid body (Yamamoto et al., 2006) and diaphragm (Zhu et al., 2003). Hypoxia also elevates SNO levels in the blood (Lipton et al., 2001; Allen et al., 2009). GSNO generated during hypoxia would promote sustained increases in ventilation by increasing intracellular free Ca2+ levels in tissues via (1) direct activation of NMDARs (Hermann et al., 2000; Chin et al., 2006) and (2) and non-NMDAR-mediated processes that potentially involve a novel set of membrane-bound GSH/GSNO receptors (Janáky et al., 2000; Chin et al., 2006). GSNO may directly or indirectly (via conversion to S-nitrosocysteinylglycine and/or SNO-L-CYS) activate carotid body chemoafferent terminals. The latter possibility is supported by evidence that SNO-L-CYS activates cardiopulmonary vagal afferents (Lewis et al., 2006). These positive actions would be counter-balanced by (1) increased NOS-mediated production of the ventilatory depressant, NO (Vitagliano et al., 1996; Gozal et al., 2000a), (2) SNO-L-CYS-mediated normalization of activated NMDARs (Choi et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2007), and (3) an increase in PDGFR-β activity (Callsen et al., 1999). The lack of roll-off in GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice suggest that the hypoxia-induced increase in GSNOR activity plays a key role in the expression of roll-off in WT mice via a decrease in GSNO levels, allowing the counter-balancing inhibitory processes to dominate. However, GSNOR degradation of GSNO results in GSSG formation (Jensen et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2001a), which activates NMDARs (Ogita et al., 1995; Varga et al., 1997; Hermann et al., 2000). Accordingly, GSNOR-mediated conversion of GSNO to GSSG would counter-balance the loss of GSNO activation of NMDARs under hypoxic challenge. The possibilities that (1) hypoxia increases GSNO levels in NOS-positive glomus cells (Lahiri et al., 2006), (2) GSNO acts intracellularly and/or as an excitatory neurotransmitter, and that (3) GSNO levels in the carotid bodies are regulated by GSNOR, are yet to be addressed.

4.6. Post-hypoxia ventilatory responses in WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice

The ventilatory responses that occurred upon cessation of hypoxic challenge (STF) were exaggerated in female GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice as compared to WT mice. In contrast, STF was not potentiated in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice. For example, although post-hypoxia fR and V̇ values were higher in male GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice than WT mice, the actual change from hypoxia values were equivalent in each group, and were equally sustained. GSNOR activity is higher in the lungs of female than male C57BL6 mice, is enhanced by S-nitrosylation, and modulated by gonadal steroids, estrogen and testosterone (Brown-Steinke et al., 2010). Since STF is markedly reduced in nNOS knock-out mice (Kline and Prabhakar, 2001; Kline et al., 2002), it would seem that nNOS produces a ventilatory excitant such as a SNO (Lipton et al., 2001) rather than a depressant such as NO (Vitagliano et al., 1996; Gozal et al., 1996, 2000a). As such, GSNOR activity in female mice may play a major role in degrading GSNO and overall protein S-nitrosylation upon return to room-air such that even partial elimination of GSNOR has a major effect on GSNO levels and the expression of STF. It could also be argued that GSNOR is less influential on GSNO levels in male mice because of relatively reduced GSNOR activity per se. Accordingly, the available GSNOR may not be able to degrade SNOs in males as efficiently as in females, such that STF expression is similar in male WT, GSNOR+/− and GSNOR−/− mice.

4.7. Conclusions and perspectives

SNOs are key regulators of cardiovascular (Liu et al., 2004; Whalen et al., 2007; Lima et al., 2010) and ventilatory control (Lipton et al., 2001; Gaston et al., 2006) systems. S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues (see Jaffrey et al., 2001) has emerged as a key mechanism by which SNOs control the function of cellular proteins (Stamler et al., 1992; Stamler, 1994; Hess et al., 2005; Whalen et al., 2007; Foster et al., 2009; Lima et al., 2010). SNOs levels and protein S-nitrosylation/de-S-nitrosylation status are regulated by multiple enzymes (Benhar et al., 2009) including GSNOR (Liu et al., 2001b; Liu et al., 2004). Inhibition of GSNOR increases intracellular SNO levels (Sanghani et al., 2009) and studies in GSNOR−/− mice have confirmed that GSNOR modulates multiple physiological processes (Liu et al., 2004; Lima et al., 2009; Whalen et al., 2007). GSNOR+/− mice behaved very similarly to GSNOR−/− mice with respect to HVR, roll-off and STF. Although it is often necessary to eliminate both genes expressing a particular protein to elicit a change in response (Zhang et al., 2010), there are examples in which functional changes exist in mice with only one gene copy (heterozygous) for a protein, including PDGFR-β+/− mice (Gozal et al., 2000b), eNOS+/− mice (Wang et al., 2011), and mice heterozygous for α2B-adrenoceptors (Duling et al., 2006). Our findings demonstrating that adult GSNOR+/− mice display differences in key resting ventilatory parameters, HVR, roll-off and STF, suggest that the partial loss of GSNOR may have implications for ventilatory control processes in humans. This would add to evidence that alterations in GSNOR activity/expression may underlie a variety of disorders such as pulmonary hypertension (Wu et al., 2010) and asthma (Que et al., 2005). Further evidence for a role of GSNOR in ventilatory control processes in mice must await pharmacological studies using GSNOR inhibitors that are directed toward understanding the role of this enzyme within the carotid bodies, brainstem and ventilatory control muscles.

Initial ventilatory responses to hypoxic challenge were similar in WT and GSNOR deficient mice.

Ventilatory roll-off occurred during hypoxic challenge in WT but not in GSNOR deficient mice.

Post-hypoxia responses were greater in female GSNOR deficient mice than female WT mice.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an NIH Program Project Grant (1P01HL101871; L.A.P, B.G., S.J.L.) and individual grants from the Department of Defense (W81XWH-07-0134; L.A.P), Galleon Pharmaceuticals (S.J.L), and NIH (R01 HL59337; B.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen BW, Stamler JS, Piantadosi CA. Hemoglobin, nitric oxide and molecular mechanisms of hypoxic vasodilation. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisswenger TB, Holmquist B, Vallee BL. chi-ADH is the sole alcohol dehydrogenase isozyme of mammalian brains: implications and inferences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:8369–8373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhar M, Forrester MT, Stamler JS. Protein denitrosylation: enzymatic mechanisms and cellular functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrm2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham AC. Neurotransmitters in the CNS control of breathing. Respir. Physiol. 1995;101:219–230. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00045-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Steinke K, deRonde K, Yemen S, Palmer LA. Gender differences in S-nitrosoglutathione reductase activity in the lung. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Kazemi H. Neurotransmitters in central respiratory control. Respir. Physiol. 2000;122:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callsen D, Sandau KB, Brüne B. Nitric oxide and superoxide inhibit platelet-derived growth factor receptor phosphotyrosine phosphatases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1544–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Huang B, Liu YC, Shyu KG, Lin PY, Wang DL. Acute hypoxia enhances proteins' S-nitrosylation in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;377:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin TY, Chueh SH, Tao PL. S-Nitrosoglutathione and glutathione act as NMDA receptor agonists in cultured hippocampal neurons. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2006;27:853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y-B, Tenneti L, Le DA, Ortiz J, Bai G, Chen H-SV, Lipton SA. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor-coupled ion channel modulation by S-nitrosylation. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:15–21. doi: 10.1038/71090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson-Welsh L. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor signals. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:32023–32026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Berkenbosch A, DeGoede J, van den Elsen M, Olievier I, van Kleef J. Influence of hypoxic duration and posthypoxic inspired O2 concentration on short term potentiation of breathing in humans. J. Physiol. (Lond) 1995;488:803–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Sarton E, Teppema L, Olievier C. Sex-related differences in the influence of morphine on ventilatory control in humans. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:903–913. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Troyer A, Kirkwood PA, Wilson TA. Respiratory action of the intercostal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:717–756. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do KQ, Benz B, Grima G, Gutteck-Amsler U, Kluge I, Salt TE. Nitric oxide precursor arginine and S-nitrosoglutathione in synaptic and glial function. Neurochem. Int. 1996;29:213–224. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(96)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Biscoe TJ. Mitochondrial function in type I cells isolated from rabbit arterial chemoreceptors. J. Physiol. 1992a;450:13–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR, Biscoe TJ. Relative mitochondrial membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in type I cells isolated from the rabbit carotid body. J. Physiol. 1992b;450:33–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulhunty A, Haarmann C, Green D, Hart J. How many cysteine residues regulate ryanodine receptor channel activity? Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2000;2:27–34. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duling LC, Cherng TW, Griego JR, Perrine MF, Kanagy NL. Loss of α2B-adrenoceptors increases magnitude of hypertension following nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H2403–H2408. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01066.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutka TL, Mollica JP, Posterino GS, Lamb GD. Modulation of contractile apparatus Ca2+ sensitivity and disruption of excitation-contraction coupling by S-nitrosoglutathione in rat muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2011;589:2181–2196. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster MW, McMahon TJ, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation in health and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2003;9:160–168. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster MW, Liu L, Zeng M, Hess DT, Stamler JS. A genetic analysis of nitrosative stress. Biochemistry. 2009;48:792–799. doi: 10.1021/bi801813n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galter D, Carmine A, Buervenich S, Duester G, Olson L. Distribution of class1,III and IV alcohol dehydrogenase mRNAs in the adult rat, mouse and human brain. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1316–1326. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann M, Tissot van Patot M, Soliz J. The neuronal control of hypoxic ventilation: erythropoietin and sexual dimorphism. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1177:151–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston B, Singel D, Doctor A, Stamler JS. S-nitrosothiol signaling in respiratory biology. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:1186–1193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1584PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri PR, Linnoila M, O’Neill JB, Goldman D. Distribution and possible metabolic role of class III alcohol dehydrogenase in the human brain. Brain Res. 1989;481:131–141. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Torres JE, Gozal YM, Littwin SM. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on cardiorespiratory responses in the conscious rat. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;81:2068–2077. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.5.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Gozal E, Simakajornboon N. Signaling pathways of the acute hypoxic ventilatory response in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Respir. Physiol. 2000a;121:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D, Simakajornboon N, Czapla MA, Xue YD, Gozal E, Vlasic V, Lasky JA, Liu JY. Brainstem activation of platelet-derived growth factor-β receptor modulates the late phase of the hypoxic ventilatory response. J. Neurochem. 2000b;74:310–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutsaeva DR, Carraway MS, Suliman HB, Demchenko IT, Shitara H, Yonekawa H, Piantadosi CA. Transient hypoxia stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in brain subcortex by a neuronal nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2015–2024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5654-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JD, Dulhunty AF. Nitric oxide activates or inhibits skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors depending on its concentration, membrane potential and ligand binding. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;173:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s002320001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxhiu MA, Chang CH, Dreshaj IA, Erokwu B, Prabhakar NR, Cherniack NS. Nitric oxide and ventilatory response to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 1995;101:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00020-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg JJ, Griffiths WJ, Nilsson SJ, Höög JO. Reduction of S-nitrosoglutathione by human alcohol dehydrogenase 3 is an irreversible reaction as analysed by electrospray mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1249–1256. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich M, Hoffmann K, König P, Gruss M, Fischbach T, Gödecke A, Hempelmann G, Kummer W. Sensory neurons respond to hypoxia with NO production associated with mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;20:307–322. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A, Varga V, Janáky R, Dohovics R, Saransaari P, Oja SS. Interference of S-nitrosolutathione with the binding of ligands to ionotropic glutamate receptors in pig cerebral cortical synaptic membranes. Neurochem. Res. 2000;25:1119–1124. doi: 10.1023/a:1007626230278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JJ, Man HS, Marsden PA. Nitric oxide signaling in hypoxia. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2012;90:217–231. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg N. The biochemistry and physiology of S-nitrosothiols. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:585–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.092501.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg N, Singh RJ, Konorev E, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. S-Nitrosoglutathione as a substrate for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Biochem. J. 1997;323:477–481. doi: 10.1042/bj3230477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakiri Y, Satoh A, Chatterjee S, Toomre DK, Chalouni CM, Fulton D, Groszmann RJ, Shah VH, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthase generates nitric oxide locally to regulate compartmentalized protein S-nitrosylation and protein trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19777–19782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605907103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janáky R, Shaw CA, Varga V, Hermann A, Dohovics R, Saransaari P, Oja SS. Specific glutathione binding sites in pig cerebral cortical synaptic membranes. Neuroscience. 2000;95:617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen DE, Belka GK, Du Bois GC. S-Nitrosoglutathione is a substrate for rat alcohol dehydrogenase class III isoenzyme. Biochem. J. 1998;331:659–668. doi: 10.1042/bj3310659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbar R, Stornetta RL, Cash DR, Lewis SJ, Guyenet PG. Photostimulation of Phox2b medullary neurons activates cardiorespiratory function in conscious rats. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2010;182:1184–1194. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0047OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplin AI, Snyder SH, Linden DJ. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-selective stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors mediates hypoxic mobilization of calcium. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:2002–2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02002.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Prabhakar NR. Role of nitric oxide in short-term potentiation and long-term facilitation: involvement of NO in breathing stability. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2001;499:215–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1375-9_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Mutant mice deficient in NOS-1exhibit attenuated long-term facilitation and short-term potentiation in breathing. J. Physiol. 2002;539:309–315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S, Roy A, Baby SM, Hoshi T, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing in the carotid body. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006;91:249–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SJ, Owen JR, Bates JN. S-nitrosocysteine elicits hemodynamic responses similar to those of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex via activation of stereoselective recognition sites. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;531:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Whorton AR. Functional characterization of two S-nitroso-L-cysteine transporters, which mediate movement of NO equivalents into vascular cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2007;292:C1263–C1271. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00382.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima B, Lam GK, Xie L, Diesen DL, Villamizar N, Nienaber J, Messina E, Bowles D, Kontos CD, Hare JM, Stamler JS, Rockman HA. Endogenous S-nitrosothiols protect against myocardial injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:6297–6302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901043106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima B, Forrester MT, Hess DT, Stamler JS. S-nitrosylation in cardiovascular signaling. Circ. Res. 2010;106:633–646. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton AJ, Johnson MA, Macdonald T, Lieberman MW, Gozal D, Gaston B. S-nitrosothiols signal the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Nature. 2001;413:171–174. doi: 10.1038/35093117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Que L, Heitman J, Stamler JS. A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans. Nature. 2001a;410:490–494. doi: 10.1038/35068596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Que L, Heitman J, Stamler JS, Steverding D. Nitrosative stress: protection by glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase. Redox. Rep. 2001b;6:209–210. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yan Y, Zeng M, Zhang J, Hanes MA, Ahearn G, McMahon TJ, Dickfeld T, Marshall HE, Que LG, Stamler JS. Essential roles of S-nitrosothiols in vascular homeostasis and endotoxic shock. Cell. 2004;116:617–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ji ES, Xiang S, Tamisier R, Tong J, Huang J, Weiss JW. Exposure to cyclic intermittent hypoxia increases expression of functional NMDA receptors in the rat carotid body. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009;106:259–267. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90626.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HT, Favre CJ, Patterson RL, Stone MR, Gill DL. Ca2+ entry activated by S-nitrosylation. Relationship to store-operated Ca2+ entry. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35318–35324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Body RL. Brain transections demonstrate the central origin of hypoxic ventilatory depression in carotid body-denervated rats. J. Physiol. 1988;407:41–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhorn DE, Eldridge FL, Waldrop TG. Prolonged stimulation of respiration by a new central neural mechanism. Respir. Physiol. 1980;41:87–103. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(80)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov SL, Richter DW. Oscillations and hypoxic changes of mitochondrial variables in neurons of the brainstem respiratory centre of mice. J. Physiol. 2001;533:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0227b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra OP, Ashraf QM, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. Hypoxia-induced activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase in the cerebral cortex of newborn piglets: the role of nitric oxide. Neurochem. Res. 2010;35:1471–1477. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss IR, Bélisle M, Laferrière A. Long-term recurrent hypoxia in developing rat attenuates respiratory responses to subsequent acute hypoxia. Pediatr. Res. 2006;59:525–530. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000203104.45807.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira L, Figueiredo-Freitas C, Casimiro-Lopes G, Magdesian MH, Assreuy J, Sorenson MM. Myosin is reversibly inhibited by S-nitrosylation. Biochem. J. 2009;424:221–231. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogita K, Enomoto R, Nakahara F, Ishitsubo N, Yoneda Y. A possible role of glutathione as an endogenous agonist at the N-methyl-D-aspartate recognition domain in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:1088–1096. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64031088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddle BM. A cytoplasmic component of pyridine nucleotide fluorescence in rat diaphragm: evidence from comparisons with flavoprotein fluorescence. Pflugers Arch. 1985;404:326–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00585343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LA, May WJ, deRonde K, Brown-Steinke K, Lewis SJ. Hypoxia-induced ventilatory responses in conscious mice: Gender differences in ventilatory roll-off and facilitation. Resp. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.11.010. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Zhang X, Song K, Wu X, Xu J. Exogenous nitric oxide-induced release of calcium from intracellular IP3 receptor-sensitive stores via S-nitrosylation in respiratory burst-dependent neutrophils. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;377:1320–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Zhang Q, Church JE, Stepp DW, Rudic RD, Fulton DJ. Role of local production of endothelium-derived nitric oxide on cGMP signaling and S-nitrosylation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2010;298:H112–H118. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00614.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que LG, Liu L, Yan Y, Whitehead GS, Gavett SH, Schwartz DA, Stamler JS. Protection from experimental asthma by an endogenous bronchodilator. Science. 2005;308:1618–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.1108228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz RN, Alves-Do-Prado W. Effects of L-arginine on the diaphragm muscle twitches elicited at different frequencies of nerve stimulation. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2001;34:825–828. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero DA, Mtui EP, Otake K, Anwar M. Central and primary visceral afferents to nucleus tractus solitarii may generate nitric oxide as a membrane-permeant neuronal messenger. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;364:51–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960101)364:1<51::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt TE, Zhang H, Mayer B, Benz B, Binns KE, Do KQ. Novel mode of nitric oxide neurotransmission mediated via S-nitroso-cysteinyl-glycine. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:3919–3925. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghani PC, Davis WI, Fears SL, Green SL, Zhai L, Tang Y, Martin E, Bryan NS, Sanghani SP. Kinetic and cellular characterization of novel inhibitors of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:24354–24362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Posterino GS. Sequential effects of GSNO and H2O2 on the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus of fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibers from the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2009;296:C1015–C1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00251.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab CA, Alander J, Brandt M, Lengqvist J, Morgenstern R, Grafström RC, Höög JO. Reduction of S-nitrosoglutathione by alcohol dehydrogenase 3 is facilitated by substrate alcohols via direct cofactor recycling and leads to GSH-controlled formation of glutathione transferase inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2008;413:493–504. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS. Redox signaling: nitrosylation and related target interactions of nitric oxide. Cell. 1994;78:931–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. Biochemistry of nitric oxide and its redox-activated forms. Science. 1992;258:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1281928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanovsky DA, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Anand D, Mandavia DN, Gius D, Ivanova J, Pitt B, Billiar TR, Kagan VE. Thioredoxin and lipoic acid catalyze the denitrosation of low molecular weight and protein S-nitrosothiols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15815–15823. doi: 10.1021/ja0529135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suko J, Drobny H, Hellmann G. Activation and inhibition of purified skeletal muscle calcium release channel by NO donors in single channel current recordings. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1451:271–287. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Shin Y, Cho SJ, Zago WM, Nakamura T, Gu Z, Ma Y, Furukawa H, Liddington R, Zhang D, Tong G, Chen HS, Lipton SA. Hypoxia enhances S-nitrosylation-mediated NMDA receptor inhibition via a thiol oxygen sensor motif. Neuron. 2007;53:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teppema LJ, Dahan A. The ventilatory response to hypoxia in mammals: mechanisms, measurement, and analysis. Physiol. Rev. 2010;90:675–754. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JE, Kreisman NR, Gozal D. Nitric oxide modulates in vitro intrinsic optical signal and neural activity in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;232:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga V, Jenei Z, Janáky R, Saransaari P, Oja SS. Glutathione is an endogenous ligand of rat brain N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) receptors. Neurochem. Res. 1997;22:1165–1171. doi: 10.1023/a:1027377605054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitagliano S, Berrino L, D'Amico M, Maione S, De Novellis V, Rossi F. Involvement of nitric oxide in cardiorespiratory regulation in the nucleus tractus solitarii. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:625–631. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)84633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Li F, Hiller S, Kim HS, Maeda N, Smithies O, Takahashi N. A modest decrease in endothelial NOS in mice comparable to that associated with human NOS3 variants exacerbates diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018766108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen EJ, Foster MW, Matsumoto A, Ozawa K, Violin JD, Que LG, Nelson CD, Benhar M, Keys JR, Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Stamler JS. Regulation of beta-adrenergic receptor signaling by S-nitrosylation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Cell. 2007;129:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiktorowicz JE, Stafford S, Rea H, Urvil P, Soman K, Kurosky A, Perez-Polo JR, Savidge TC. Quantification of cysteinyl S-nitrosylation by fluorescence in unbiased proteomic studies. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5601–5614. doi: 10.1021/bi200008b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem. J. 1967;103:514–527. doi: 10.1042/bj1030514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Du L, Xu X, Tan L, Li R. Increased nitrosoglutathione reductase activity in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;113:32–40. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09279fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Henrich M, Snipes RL, Kummer W. Altered production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in rat nodose ganglion neurons during acute hypoxia. Brain Res. 2003;961:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, König P, Henrich M, Dedio J, Kummer W. Hypoxia induces production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in glomus cells of rat carotid body. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;325:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Piston DW, Goodman RH. Regulation of corepressor function by nuclear NADH. Science. 2002;295:1895–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.1069300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Heunks LM, Ennen L, Machiels HA, Dekhuijzen PN. Role of nitric oxide in isometric contraction properties of rat diaphragm during hypoxia. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;88:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]