Abstract

Purpose

According to the World Health Organization, quality of life (QOL) includes physical and mental health, emotional well-being, and social functioning. Using an adaptation of Andersen's behavioral model, we examined the associations between the three dimensions of QOL and needs and health behaviors in a nationally representative sample of adults 65 years and older.

Methods

A representative sample from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) was used. NHANES over-samples persons 60 years and older, African Americans, and Hispanics. Frequencies and distribution patterns were assessed, followed by bivariate and multiple regression analyses.

Results

These older adults reported high levels of QOL. However, associations between needs and health behaviors and QOL varied across dimensions. Activities of daily living (ADL) were associated with all three dimensions. Depression was associated with two dimensions and memory problems with one dimension. Physical activity was linked to social functioning, and health care utilization was linked to emotional well-being.

Conclusions

The differences in associations with different dimensions of QOL confirm that this is a multidimensional concept. Since depression, memory problems, and ADL function were all associated with some dimension of QOL, future interventions to improve QOL in older adults should include screening and treatment for these problems.

Keywords: Quality of life, Social functioning, Emotional well-being, Older adults, NHANES 2005–2006

Introduction

Currently, one in eight Americans is over 65 years of age [1]. By 2050, more than 33 million persons in the United States (US) will be aged 65–74 years, while 30 million will be between 75 and 84 years, and 20.5 million will be over the age of 85 years [1]. The quality of older adults’ lives is receiving increased attention. A recent report from the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [2] noted that QOL decreased in the US population as a whole from 1993 to 2001. Both the increase in the proportion of the population over 65 years of age and the reported decrease in QOL underscore the need to examine factors associated with QOL in older adults.

Quality of life (QOL) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) [3] as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.” The WHO further notes that QOL is a concept with several domains, including physical and mental health, social functioning, and emotional well-being. QOL has been conceptualized in many ways depending on the discipline, paradigm, and time frame of research examining QOL [4]. QOL measurements also vary. Broad measures such as the WHOQOL-BREF instrument include several dimensions of QOL in one scale. Other instruments such as the SF-36 scale are health-related measures. Some are disease specific such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL questionnaire. Finally, there are domain-specific measures such as the Rand Social Support Scale [4].

The broader QOL measures have been most widely used. Proponents of these broad measures note that QOL is an overarching concept that reflects the physical, mental, and social aspects of an individual's life [5]. Others, however, point out that broad QOL measures may obscure important nuances [6]. For example, an elderly person with chronic illnesses may have poor health-related QOL but high non-health-related QOL. Therefore, in any study, it is important to decide whether a broad QOL measure or measures of specific dimensions are most appropriate.

Similarly, there are discussions as to what constitutes old or elderly [7]. Most developed countries have accepted the chronological age of 65 years as a definition of ‘elderly’ or older person. It is often associated with the age at which one can begin to receive pension benefits. This common use of a calendar age to mark the threshold of old age does not assume that biological aging starts at 65. There is great variability in biological aging, and it is generally accompanied by decline in one or more of a person's abilities in the physical and cognitive domains [8]. It is well established that decline in one or more of a person's abilities is associated with reductions in QOL [5]. However, the degree to which and the dimensions of QOL affected will vary depending on the extent of decline in abilities and other factors specific to individuals. Understanding the connections between biological aging, individual factors, and the dimensions of QOL is important for planning of interventions and services to enhance QOL in older adults.

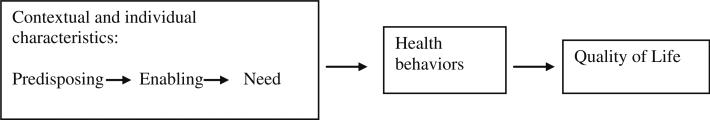

In the study reported here, Andersen's behavioral model [9] was used to assess factors associated with QOL in older adults. The model depicts how contextual and individual characteristics, which include predisposing factors such as demographics, enabling factors such as social, human, and material resources, and need factors such as number of chronic conditions, activities of daily living (ADL), and mental status, influence health behaviors and QOL (Fig. 1). Health behaviors include physical activity and health care utilization while QOL includes the following: health-related QOL (HQOL), social functioning, and emotional well-being. Previous studies have found that both QOL and HQOL are associated with predisposing and enabling factors including age gender, ethnicity, education, income, marital status, and family size [2, 10–15]. In addition, HQOL has been shown to be influenced by the number and severity of chronic diseases, though social functioning was less affected by these [16, 17]. Moreover, lower ADL function, depression, and memory problems have been linked to poorer QOL [15, 18–20]. Finally, health behaviors such as physical activity and health care utilization have been associated with QOL [21–25]. However, the relationship between health care utilization and QOL has varied. Less use of health care services was associated with better QOL in asthma patients and female veterans, but for male veterans and health care services obtained specifically for preventive services, QOL was worse [23–25].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model. Adapted from Andersen's behavioral model [9]. Factors associated with quality of life in older adults in the United States

In summary, all the variables in the Andersen model have been linked to QOL. However, the relationships between the different dimensions of QOL in older adults and various contextual and individual characteristics and health behaviors are not clear. Therefore, this study examined three dimensions of QOL in community-dwelling older adults. We hypothesized that controlling for predisposing factors, a person's needs (number of chronic conditions, ADL function, and mental status), and health behaviors (physical activity and health care utilization) would be linked to HQOL, social functioning, and emotional well-being.

Methods

This descriptive, correlational study used secondary data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2005 to 2006. The NHANES from the National Center for Health and Human Services [26] is a national survey designed to assess the prevalence of major diseases and risk factors for diseases, with the aim of assessing nutritional status and its associations with health promotion and disease prevention. Data are collected through both personal interviews conducted and physical examinations carried out at mobile examination centers. The NHANES examines a nationally representative sample of approximately 5,000 individuals each year from the civilian, non-institutionalized US population. The sample is chosen in four stages; first strata are determined based on geographic location, and then, a random sample of 15 US counties is selected within strata (mainly single counties or contiguous counties). Stratified sampling is used to capture all ages of the US population. To produce reliable statistics, NHANES oversamples persons 60 years and older, African Americans, and Hispanics. For this study, we used data from personal interview modules for individuals 65 years or older. The study included 16 variables. Some were extracted directly from the data set, and others were created as we explain below.

Measures

QOL

In Andersen's behavioral model, outcomes include perceived health and satisfaction [9]. We expanded these outcomes to the broader concept QOL. Participants’ QOL was measured using 3 variables: HQOL, social functioning, and emotional well-being. The HQOL score was a composite of the number of physically and mentally unhealthy days in the past month. In two NHANES questions, participants were asked how many days during the past 30 days their physical health was not good and how many days their mental health was not good. These single items and the composite score have been validated in test–retests and against reported health conditions, physical exams, and broader instruments such as the SF-36 and the WHOQoL-BREF [27, 28]. The distribution of HQOL clearly showed two modes with 56.6% of the sample reporting no days of physical or mental unhealth and 12% reporting 30 unhealthy days. In order to improve the data with respect to the shape of the distribution, a revised HQOL variable was created with 6 levels: no unhealthy days = 0, one to five = 1, six to ten = 2, eleven to fifteen = 3, sixteen to twenty-nine = 4, and thirty = 5.

For social functioning, we created an index using two questions: number of close friends and how often a person attended church or religious services. A social functioning index based on previous NHANES data using four questions has shown a high level of predictability of the social functioning dimension of QOL [29]. However, two of those questions were not available in the NHANES 2005–2006 data, so a two question index was created. After examining distributions of the number of close friends, participants could feel at ease with, could talk to about private matters, and could call on for help, and we assigned a value of 0 for no close friends, 1 for one close friend, 2 for two close friends, 3 for three close friends, and 4 for four or more close friends. For yearly church or religious services attendance, we assigned a value of 0 to never, 1 to once, 2 to two, and 3 for three or more. Thus, the index score for social functioning ranged from 0 to 7 with higher scores representing better social functioning.

The emotional well-being score was also created using two questions. The first question asked whether there was anyone to provide emotional support. A value of 1 was assigned for yes and a value of 0 for no. The second question asked whether more emotional support had been needed in the last year: an answer of no = 1 and a yes = 0. The index score thus had a possible range of 0–2 with higher scores, indicating better emotional well-being.

Health behaviors

Health behaviors are, according to Andersen's behavioral model, defined as actions people do to stay healthy or improve health. For this study, health behaviors included physical activity and health care utilization, both of which have been linked to increased age [9, 21–23]. While the NHANES data included other health behaviors, these two behaviors seemed most likely to be affected by increasing age. Physical activity was operationalized as level of physical activity performed on average each day, ranging from 1 = sits during the day and does not walk about very much, 2 = stands or walks about a lot during the day, but does not have to carry or lift things very often, 3 = lifts load or has to climb stairs or hills often, to 4 = does heavy work or carries heavy load. Health care utilization was coded as number of times a respondent had received any type of health care in the last year: no health care utilization = 0, one visit = 1, two to three visits = 2, four to nine visits = 3, ten to twelve visits = 4 and thirteen or more = 5.

Contextual and individual characteristics

In Andersen's behavioral model, contextual and individual characteristics are conceptualized as factors that impede or enhance individual's health behaviors, most notably health care utilization and subsequent other outcomes related to health and satisfaction [9]. The model divides the characteristics into predisposing demographic, enabling socioeconomic, and need for care factors. In our study, predisposing, enabling and need factors were captured by seven variables. Predisposing factors included demographic variables such as age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Age was a continuous variable from age 65 to age 85 or above. Race/ethnicity was classified as Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other.

Enabling factors were operationalized as social, human, and material resources, including individuals’ immediate social connections such as number of people in the family, marital status, education, and poverty level. Social resources were defined as number of people in the family and marital status. Number of people in the family was the total number of related people in the household including the respondents; scores of 1–6 reflected the actual number and 7 was used for seven or more people. Marital status was coded as married or not married (widowed, divorced, separated, or never married). Human resources included education, coded as a high school degree or more or less than a high school degree. Material resources were based on a poverty income ratio. This ratio, provided in NHANES, was the ratio of the family income to the poverty threshold. A lower number represented a lower income.

Needs factors were operationalized as number of chronic conditions, ADL function, and mental status. We created a score for number of chronic conditions using participants’ answers to questions about whether they had ever been told by a doctor that they had a particular condition. Thirteen conditions, including pulmonary, cardiovascular, cancer, stroke, kidney, diabetes, liver, and arthritis illnesses, were scored for a score range of 0–13. ADL function was the sum of 16 items on the Activities of Daily Living scale, which measures constructs associated with locomotion and transfers, household productivity, social integration, and manipulation of surroundings [30]. Items scored from 1 to 4 where 1 = no difficulty, 2 = some difficulty, 3 = much difficulty, and 4 = unable to do for a total score range from 16 to 64. Higher scores indicated lower ADL function. Mental status was operationalized as memory problems and depression. One question asked whether a person had memory problems or not. Depression was the total score on the depression module in the Patient Health Questionnaire, a self-administered version of the PRIME-MD diagnostic instrument for common mental disorders. The module contains 9 DSM-IV items asking participants whether they have been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the last 2 weeks. Item scores range from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day for a total scale score of 0–27 [31]. Higher scores indicate more depression.

Analyses

Means and percentages were used to summarize the characteristics of study subjects. Linear regression was used to examine associations between the independent variables described earlier and the three QOL dimensions. For each of the three QOL measures, we first examined bivariate relationships by linking each of the needs and health behavior variables to the specific QOL measure. We next constructed multivariate models by linking all the needs and health behavior variables together to the specific QOL measure. Both models controlled for age, gender, race, family size, marital status, education, and poverty index. All descriptive and regression analyses took into account the complex NHANES survey design, including stratification, clustering, and unequal weighting. Hence, analyses were performed in SAS survey procedures using the whole NHANES data set with a subpopulation statement for people 65 years and older.

Results

The 2005 NHANES sample contained 911 adults 65 years or older with no missing values in the 16 variables described earlier (see Table 1). Our initial sample was 1,189, but 278 had missing data on one or more of the 16 variables we extracted or created. Missing data were more common in older people who were less likely to be married and had worse ADL function, more memory problems, lower physical activity levels, and worse QOL in all three dimensions. The majority of the final sample of 911 were female (56.8%), and their average age was 73.6 years. Most identified themselves as white (84.9%), with 8.2% black and 5.1% Hispanics. Their family size was an average of 1.9 people, and 57.8% were married. The majority had a high school degree or more education (72%) and were above the poverty threshold (poverty index 2.67). On average, these older adults reported 2.5 chronic conditions and no difficulty to some difficulty with ADL function (score = 21.27). Only 14% reported memory problems and few had been depressed in the last two weeks (score = 2.22). The average score on physical activity (1.96) indicated that most of the sample stood or walked a lot during the day, but did not have to carry or lift things very often. On average, participants received health care two to nine times a year. The HQOL score was 1.22, indicating an average of more than five but less than ten unhealthy days in the last 30 days. The average score on social functioning was high at 5.16, indicating that most had at least two close friends and had attended church or other religious services more than once in the last year. The average score on emotional well-being was 1.74, indicating that most people had someone to provide emotional support and received all the emotional support they needed in the past year.

Table 1.

Characteristics of adults in the US population 65 years and older

| Overall (n = 911) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual and individual characteristics | ||

| Predisposing | ||

| Demographics | ||

| Gender—female | 56.8% | |

| Age, years | 73.58 (0.24) | (65–85) |

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 5.1% | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.2% | |

| Other | 1.7% | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 84.9% | |

| Enabling | ||

| Social resources | ||

| Number of people in family | 1.90 (0.04) | (1–7) |

| Marital status—yes | 57.8% | |

| Human resources | ||

| Education (≥high school) | 72.0% | |

| Material resources | ||

| Poverty index | 2.67 (0.10) | (0.05–5) |

| Need | ||

| Number of chronic illnesses | 2.46 (0.09) | (0–13) |

| Activities of daily living (ADLs) | 21.27 (0.25) | (16–54) |

| Mental status | ||

| Memory problems—yes | 14.0% | |

| Depression | 2.22 (0.14) | (0–17) |

| Health behaviors | ||

| Physical activity | 1.96 (0.06) | (1–4) |

| Health care utilization | 2.74 (0.05) | (0–5) |

| Quality of life | ||

| Health-related quality of life | 1.22 (0.07) | (0–5) |

| Social functioning | 5.16 (0.08) | (0–7) |

| Emotional well-being | 1.74 (0.03) | (0–2) |

NHANES 2005–2006 (n = 911) Values are expressed as mean (SE) or percent

When examined individually, all the needs and health behavior variables were significantly associated with at least one QOL dimension, controlling for age, gender, race, family size, marital status, education, and poverty index (Table 2). Specifically, lower ADL function, memory problems, and more depression were associated with poorer QOL in all three dimensions. A higher number of chronic conditions were associated with both poorer HQOL and social functioning, while greater health care utilization and lower physical activity were associated with poorer HQOL.

Table 2.

Health-related quality of life, social functioning, and emotional well-being in us adults 65 years and older

| Quality of life |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-related quality of life |

Social functioning |

Emotional well-being |

||||

| Variables Needs or health behaviors | Estimate (SE) | p-value | Estimate (SE) | p-value | Estimate (SE) | p-value |

| Number of chronic illnesses | 0.152 (0.03) | <0.001 | –0.116 (0.04) | 0.008 | –0.003 (0.02) | 0.826 |

| Activities of daily living (ADL) | 0.068 (0.01) | <0.001 | –0.045 (0.01) | 0.002 | –0.011 (0.00) | 0.002 |

| Memory problems | 0.850 (0.26) | 0.006 | –1.102 (0.19) | <0.001 | –0.166 (0.04) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.293 (0.02) | <0.001 | –0.081 (0.02) | 0.001 | –0.050 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Health care utilization | 0.227 (0.06) | 0.001 | –0.023 (0.04) | 0.617 | –0.004 (0.02) | 0.847 |

| Physical activity | –0.257 (0.07) | 0.002 | 0.240 (0.15) | 0.138 | –0.016 (0.03) | 0.595 |

NHANES 2005–2006 (n = 911)

Estimate: regression coefficient (SE); Regression coefficient for each variable (Needs and health behaviors) adjusted for age, gender, race, family size, marital status, education, and poverty index

In the full models, when all needs and health behavior variables were included, poorer HQOL was associated with having a high school degree or higher, lower ADL function, and more depression (Table 3). When full models for social functioning and emotional well-being were analyzed, social functioning was higher in people who were older, female, black, married, with a high school education or higher, and with better ADL function, no memory problems, and greater health care utilization. Emotional well-being was lower in people who were Hispanic and black, with lower ADL function, more depression, and less physical activity.

Table 3.

Multivariate results for health-related quality of life, emotional well-being, and social functioning in US adults 65 years and older (n = 911)

| Variable | Health-related quality of life |

Emotional well-being |

Social functioning |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | p value | Estimate | SE | p value | Estimate | SE | p value | |

| Age | –0.013 | 0.01 | 0.076 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.133 | 0.030 | 0.01 | 0.034 |

| Female | 0.191 | 0.13 | 0.174 | 0.039 | 0.04 | 0.311 | 0.510 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (vs. white) | 0.242 | 0.14 | 0.106 | –0.137 | 0.05 | 0.010 | –0.064 | 0.31 | 0.840 |

| Black (vs. white) | 0.087 | 0.11 | 0.462 | –0.101 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.448 | 0.17 | 0.020 |

| Other (vs. white) | 0.333 | 0.51 | 0.527 | 0.009 | 0.11 | 0.935 | –0.447 | 0.62 | 0.148 |

| Family size | 0.035 | 0.04 | 0.411 | 0.019 | 0.01 | 0.135 | 0.062 | 0.08 | 0.471 |

| Marital status (married vs. not married) | –0.011 | 0.11 | 0.920 | 0.032 | 0.04 | 0.375 | 0.452 | 0.20 | 0.039 |

| Education (≥high school vs. <high school) | 0.237 | 0.09 | 0.018 | –0.024 | 0.03 | 0.480 | 0.518 | 0.21 | 0.030 |

| Poverty index | –0.012 | 0.03 | 0.703 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.285 | 0.071 | 0.04 | 0.105 |

| Number of chronic illnesses | –0.003 | 0.03 | 0.925 | 0.011 | 0.01 | 0.332 | –0.077 | 0.04 | 0.072 |

| Activities of daily living (ADL) | 0.034 | 0.01 | <0.001 | –0.007 | 0.00 | <0.001 | –0.024 | 0.01 | 0.023 |

| Memory problems (yes vs. no) | 0.172 | 0.28 | 0.542 | –0.046 | 0.03 | 0.192 | –0.900 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.263 | 0.02 | <0.001 | –0.035 | 0.01 | <0.001 | –0.040 | 0.02 | 0.134 |

| Health care utilization | 0.043 | 0.05 | 0.387 | 0.014 | 0.01 | 0.223 | 0.123 | 0.05 | 0.030 |

| Physical activity | –0.024 | 0.07 | 0.751 | –0.045 | 0.02 | 0.033 | 0.108 | 0.14 | 0.454 |

Discussion

This nationally representative sample of community-dwelling people 65 years and older reported high QOL in all three dimensions. In bivariate analyses, the need variables, ADL function, memory problems, and depression were associated with all three QOL dimensions, while the number of chronic conditions was associated with HQOL and social functioning. However, in our full models, only ADL function was significantly related to all three dimensions of QOL.

In previous studies, ADL or physical function was associated with social functioning in older women. Our results that memory problems were associated with social functioning, and depression with HQOL and emotional well-being are somewhat different from previous studies where memory problems defined both as working memory and executive function and depression were associated with only HQOL [18–20]. Our finding that number of chronic conditions was not associated with any QOL dimension is also different from previous studies that found number of chronic diseases associated with HQOL in older adults [13, 18, 32]. The differences in results from bivariate and full model analyses suggest that the needs variables may affect each other, a relationship that needs further examination. Future studies are needed to explore how different needs affect each other and different dimensions of QOL. Even so, our findings underscore the importance of diagnosis and treatment of lower ADL function, memory problems, and depression to improve the dimensions of older adults’ QOL.

The two health behaviors examined were associated with one QOL dimension, but neither was associated with HQOL. Less physical activity was associated with better emotional well-being. Thus, these older adults experienced more emotional well-being when they did not have to do higher levels of physical activity such as heavy lifting or strenuous activity on a regular basis. The second health care behavior examined, greater health care utilization, was linked to lower social functioning. This association may have been a function of limited time for social activities when more time is spent on contacts with heath care providers. Another plausible explanation is that higher health care utilization may have been a proxy for more extensive health problems, which themselves could limit social functioning. More in-depth examination of physical activity using other measures as well as health care utilization and QOL is warranted.

There were several limitations to our study. First, the findings were based only on subjects who had complete data. The initial sample was 1,189, but 278 had missing data, When we compared those with missing data and those included in the study, we did find differences. Since people with missing data scored worse on QOL, using only the sample with no missing data provided an estimate of better QOL than it should be for the whole representative sample of community-dwelling older adults. In addition, results presented from regression analyses assumed that data were missing at random; however, we cannot test for that, so our results might have been different if this assumption was not met. In our analysis to examine missing data patterns, we found that people with missing data were older, less likely to be married, had worse ADL function, more memory problems, lower physical activity, and lower QOL. Second, all our QOL measures were generated from population-based measures. Thus, the study was limited to testing associations between variables reflecting computed and transformed QOL measures. While the two item HQOL has been validated against longer HQOL measures [27, 28], our transformations have not been validated. Also, the two-item index we computed for social functioning did not capture the multifunctionality of social functioning. It would have been preferable for the NHANES data to include all four domains in the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index, including church or other religious group membership and membership in other community organizations [33]. Third, in the NHANES survey, memory problems were measured by self-report, rather than an objective measure. Thus, it is possible that older adults underreported or were unaware of their memory problems. Fourth, because the NHANES database limits the response choices for the categorization of age that includes a category of over the age of 85, it is possible that the oldest-old are not adequately represented in our findings. Finally, we used cross sectional data so we are reporting associations, not causal links. Longitudinal analyses are needed to examine temporal relationships of these variables with QOL.

Nevertheless, the study found differences in the contextual and individual characteristics and health behaviors associated with the dimensions of QOL in these community-dwelling adults 65 years and older. The finding that different dimensions of QOL were associated with different factors confirms the emerging consensus that QOL is a multidimensional construct and needs to be measured as such [4]. The findings are also useful for designing interventions to improve QOL in the growing population of older adults. Since depression, memory problems, and ADL function were all associated with some dimension of QOL, future interventions to improve QOL in older adults should include interventions such as screening and treatment for these problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an individual training grant (K01 NR0105556) and a grant from the Rural Healthcare Research Center (R3P20NR009009-05S1) both from the National Institute of Nursing Research, and a grant from the Jeanette Lancaster Fund, School of Nursing University of Virginia. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institute of Health.

Contributor Information

Marianne Baernholdt, School of Nursing and Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA baernholdt@virginia.edu.

Ivora Hinton, School of Nursing, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Guofen Yan, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Karen Rose, School of Nursing, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Meghan Mattos, School of Nursing, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

References

- 1.National Institute on Aging . Why population aging matters: A global perspective. National Institute of Health Publication # 07–6134; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahran HS, Kobau R, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Holt J, Donehoo R, et al. Health-related quality of life surveillance-United States, 1993–2002. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries/CDC. 2005;54(4):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Measuring quality of life: The development of the world health organization quality of life instrument (WHOQOL) World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hambleton P, Keeling S, McKenzie M. The jungle of quality of life: Mapping measures and meanings for elders. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2009;28(1):3–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White SM, Wojcicki TR, McAuley E. Physical activity and quality of life in community dwelling older adults. [Dec 12, 2010];Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009 7(10) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-10. http://www.hqlo.com/content/7/1/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawton M. Quality of life in chronic illness. Gerontology. 1999;45:181–183. doi: 10.1159/000022083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . Health statistics and health information systems. The World Health Organization.; 2010. [Dec 12, 2010]. Definition of older or elderly person. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michael YL, Colditz GA, Coakley E, Kawachi I. Health behaviors, social networks, and healthy aging: Cross-sectional evidence from the nurses’ health study. Quality of Life Research. 1999;8:711–722. doi: 10.1023/a:1008949428041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Medical Care. 2008;46(7):647–653. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandiera FC, Pereira DB, Arif AA, Dodge B, Asal N. Race/ethnicity, income, chronic asthma, and mental health: A cross-sectional study using the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(1):77–84. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815ff3ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skarupski KA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Scherr PA, Zack MM, Moriarty DG, et al. Black-white differences in health- related quality of life among older adults. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(2):287–296. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fryback DG, Dunham NC, Palta M, Hanmer J, Buechner J, Cherepanov D, et al. US Norms for six generic health-related quality-of-life indexes from the national health measurement study. Medical Care. 2007;45(12):1162–1170. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814848f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopman WM, Harrison MB, Coo H, Friedberg E, Buchanan M, VanDen Kerkhof EG. Associations between chronic disease, age and physical and mental health status. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 2009;29(3):108–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borders TF, Aday LA, Xu KT. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among an older population in a largely rural western region. Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20(1):67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaninotto P, Falaschetti E, Sacker A. Age trajectories of quality of life among older adults: Results from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(10):1301–1309. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Ntetu AL, Maltais D. Relationship between multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. [Dec 20, 2010];Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004 2(51) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-51. http://www.hqlo.com/content/2/1/51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortin M, Bravo G, Lapointe L, Almirall J, Dubois MF, Vanesse A. Relationship between multimorbidity and health-related quality of life of patients in primary care. Quality of Life Research. 2006;15(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-8661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lima MG, Barros MBA, Cesar CLG, Goldbaum M, Carandina L, Ciconelli RM. Impact of chronic disease on quality of life among the elderly in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil: A population-based study. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica = Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2009;25(4):314–321. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson CO, Belue R, Schlundt DG, McClellan L. Relationship between symptoms of depression, functional health status, and chronic disease among a residential sample of African Americans. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2006;29(2):133–140. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis JC, Marra CA, Najafzadeh M, Liu-Ambrose T. The independent contribution of executive functions to health related quality of life in older women. BMC Geriatrics. 2010;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics . Older Americans 2008: Key indicators of well-being. US Government printing office; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rust G, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Daniels E, Strothers H, Satcher D. Modifiable determinants of healthcare utilization within the African-American population. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96(9):1169–1177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simmons LA, Anderson EA, Braun B. Health needs and health care utilization among rural, low-income women. Women and Health. 2008;47(4):53–69. doi: 10.1080/03630240802100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams SA, Wagner S, Kannan H, Bolge SC. The association between asthma control and health care utilization, work productivity loss and health-related quality of life. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(7):780–785. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181abb019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallegos-Carrillo K, Garcia-Pena C, Duran-Munoz C, Mudgal J, Duran-Arenas L, Salmeron-Castro J. Health care utilization and health-related quality of life perception in older adults: A study of the Mexican social security institute. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2008;50(3):207–217. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Sept 22, 2009];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2009 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm.

- 27.Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R. The center for disease control and prevention's healthy days measures—population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. [Dec 12, 2010];Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003 1(37):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-37. http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toet J, Raat H, van Ameijden EJ. Validation of the Dutch version of the CDC core healthy days measures in a community sample. Quality of Life Research. 2006;15(1):179–184. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-8484-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford ES, Merritt RK, Heath GW, Powell KE, Washburn RA, Kriska A, et al. Physical activity behaviors in lower and higher socioeconomic status populations. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;133(12):1246–1256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook CE, Richardson JK, Pietrobon R, Braga L, Silva HM, Turner D. Validation of the NHANES ADL scale in a sample of patients with report of cervical pain: Factor analysis, item response theory analysis, and line item validity. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2006;28(15):929–935. doi: 10.1080/09638280500404263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nobrega TC, Jaluul O, Machado AN, Paschoal SM, Filho WJ. Quality of life and multimorbidity of elderly outpatients. Clinics Sao Paulo Brazil. 2009;64(1):45–50. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A 9 year follow-up study of Alameda county residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]