Abstract

Background

To promote effective genome-scale research, genomic and clinical data for large population samples must be collected, stored, and shared.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with 45 members of a Seattle-based integrated healthcare delivery system to learn about their views and expectations for informed consent in genome-scale studies.

Results

Participants viewed information about study purpose, aims, and how and by whom study data could be used to be at least as important as information about risks and possible harms. They generally supported a tiered consent approach for specific issues, including research purpose, data sharing, and access to individual research results. Participants expressed a continuum of opinions with respect to the acceptability of broad consent, ranging from completely acceptable to completely unacceptable. Older participants were more likely to view the consent process in relational – rather than contractual – terms, compared with younger participants. The majority of participants endorsed seeking study subjects’ permission regarding material changes in study purpose and data sharing.

Conclusions

Although this study sample was limited in terms of racial and socioeconomic diversity, our results suggest a strong positive interest in genomic research on the part of at least some prospective participants and indicate a need for increased public engagement, as well as strategies for ongoing communication with study participants.

Keywords: Informed consent, participant views, genomic research, biobank, research ethics

Genome-scale studies are a powerful tool for advancing our understanding of how genes affect biology and, ultimately, human health; at the same time, the scope, speed, and uncertain outcomes of such research challenges prevailing approaches to human subjects protections and informed consent. Conceptions of risk and harm are central to the paradigm of participant protections grounded in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. The ethical conduct of research involving human participants requires at least three things: (1) the benefits researchers hope to realize from the study must outweigh the potential harms to participants; (2) would-be participants must be given sufficient information about what is entailed in study participation (including risks and possible harms) to make a reasoned choice about whether to take part; and (3) participation must be voluntary and free of coercion.

Genome-scale research is exploratory in nature. In general, these studies seek to identify associations between genotypes (one’s genetic makeup) and phenotypes (one’s observable or measurable physical characteristics, health/disease status, etc.) to identify targets for further research aimed at understanding disease biology and identifying potential therapeutic approaches. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and similar large-scale research approaches therefore require large numbers of participants and unprecedented depth of information on each participant. To better understand gene-environment interactions, in particular, researchers often seek additional risk-related data (e.g., eating habits, exercise, environmental and occupational exposures, education level, and/or socioeconomic status).

To facilitate timely translation of discovery research findings into health applications, current federal policies (National Institutes of Health 2003, 2007) strongly encourage data sharing within the research community through repositories such as the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) (Mailman et al. 2007) and the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB) (Thorn, Klein, and Altman 2010), thereby increasing the potential for participants’ study data to be used by others, for study purposes beyond what participants may believe they agreed to. Furthermore, despite the best efforts of bioinformaticians to render such data fully de-identified (and safe from re-identification), such strategies cannot deliver absolute protection (Ohm 2010).

Much expert ink has been spilled on these issues (Greely 2007; Maschke 2010; McGuire and Gibbs 2006; Rothstein 2010), but relatively little is known about the views of research participants and members of the general public with respect to informed consent. We conducted focus groups with members of a large integrated healthcare delivery system to learn about their views and expectations about a variety of issues that come up in GWAS and similar kinds of genomic research. This report describes our findings related to the following questions: What do potential research participants believe ought to be addressed in the informed consent process for genome-scale studies? What approaches to providing study information do they prefer? When do they think researchers should seek study subjects’ consent for changes in research plans?

METHODS

We conducted 6 focus groups with randomly selected members of Group Health Cooperative, a large integrated healthcare delivery system based in Seattle, Washington, from March – August 2008. To be eligible to participate, individuals needed to be current Group Health members; be competent to provide informed consent; be able to communicate in English; and be able to attend the focus group session in person. We held 2 separate sessions each with members aged 18 – 34; members aged 35 – 50; and members older than 50 years. Age stratification was performed to explore whether age-related differences in views might exist, particularly around privacy and confidentiality. The study design and materials were reviewed and approved by the Group Health Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Within each age group, candidates were identified at random through a query of administrative data. Initial recruitment was by letter, followed by up to 3 telephone calls. Of those who were reached by telephone and determined to be eligible, 31% agreed to participate. We offered refreshments and a $50 cash payment, as well as parking reimbursement or cab fare, to encourage participation. Individuals who agreed to participate were mailed an informational packet that included a welcome letter with a number to call with questions, logistical information, and a copy of the consent form. At the beginning of each session, one of the facilitators reviewed the consent materials with the group and answered any questions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

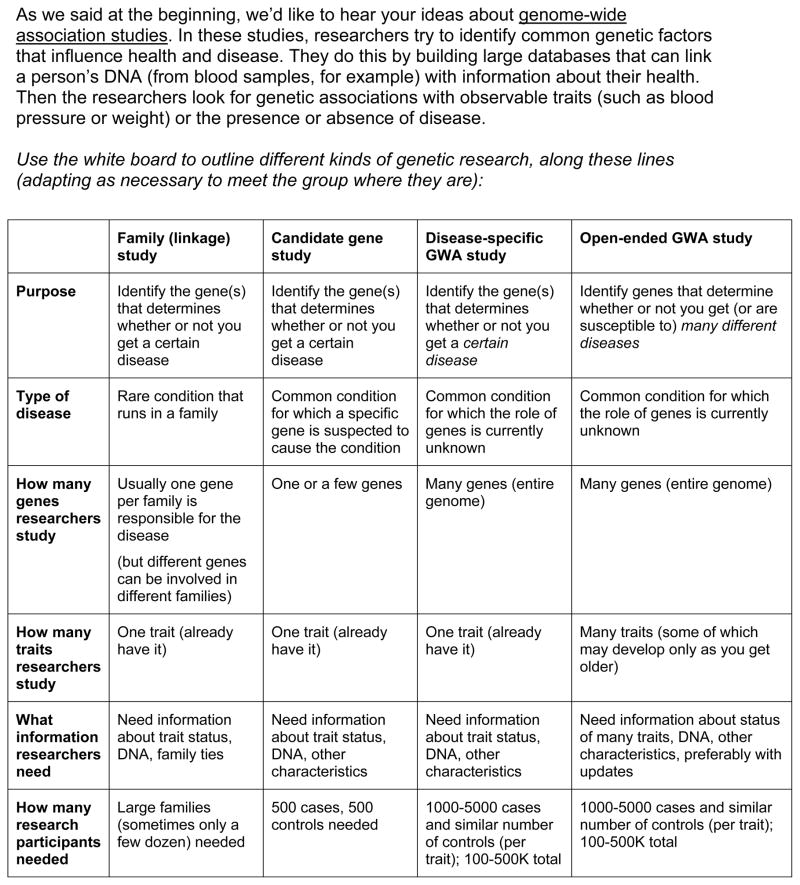

Each two-hour discussion was co-facilitated by two members of the research team using a written guide that had been pilot-tested with 5 health plan members (see Figures 1–3 for excerpts from the moderator’s guide as well as Trinidad, Fullerton, Bares, et al. 2010). Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed. Following each focus group, we wrote detailed field notes. These were revised in round-robin fashion by the 2 or 3 investigators present at the session (a note-taker plus facilitators); the field notes were then reviewed by another team member who did not attend, with the aim of providing an outside perspective and identifying any needed changes to the discussion guide. For the current analysis, two members of the research team (SBT and SMF) did several close readings of the transcripts to gain a sense of major themes with respect to informed consent, re-consent, return of research findings, and risk. One of us (SBT) then grouped the findings into the more specific subcategories described below, with detailed review and discussion with another team member (SMF); two other team members familiar with the data (JMB and WB) reviewed the analysis. A more detailed description of methods has been published previously (Trinidad et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Warm-up

Figure 3.

Topic 2 – How Participants’ Information may be Used*

RESULTS

A total of 45 participants took part in these discussions. The mean age of participants was 45 years, and 40% were female (age and sex breakdowns for the different age categories are shown in Table 1). The large majority of participants were white (89%) and college-educated (78% had earned at least a bachelor’s degree). Words that appear within quotation marks in this section are direct quotations from focus group participants. In what follows, “participants” is used to refer to focus group participants, and “study subjects” refers to notional participants in genetic research. Where differences regarding views about informed consent were identified among age groups, those are noted; other age differences have been reported previously (Trinidad et al. 2010).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Age 18–34 | Age 35–49 | Age≥50 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 14 | 15 | 45 |

| Age range (actual) | 18–34 | 37–49 | 51–84 | 18–84 |

| Mean age (years)* | 27.1 | 42.8 | 62.7 | 44.8 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 7 | 10 | 10 | 27 (60%) |

| Female | 9 | 4 | 5 | 18 (40%) |

| Race** | ||||

| White | 14 | 13 | 13 | 40 (89%) |

| American Indian/ Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 (11%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Black | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 (4%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 16 | 14 | 12 | 42 (93%) |

| Declined | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (7%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 10 | 13 | 12 | 35 (78%) |

| Household income>$75k | 4 | 12 | 7 | 23 (51%) |

excludes 4 participants who declined to provide age

some participants reported multiple categories

Desired informational content

“Informed consent” can be understood as having two parts: the informational content to be shared with all potential subjects, and the process by which researchers provide that information, answer questions, and document study subjects’ agreement to take part. Following a brief educational presentation about how GWAS are conducted, we asked focus group participants what they would need to know in order to decide whether to take part in such a study. Participants’ first responses often had to do with the purpose of the research and the hoped-for benefits of the study to society. For example, one participant answered, “Where you want to go with [the research].” Another stated, “I would want to know the specifics of what the information was going to. I couldn’t see myself putting my information out there without knowing what it was for.”

Focus group participants also wanted to know up front which data about study subjects would be shared, and with whom. One session included this exchange:

Participant A: “My concern would be much less around what the research is about than where does the information go?”

Participant B: “And who has access to it?”

Another commented, “I wouldn’t have a problem [with data sharing], as long as I knew to what extent I was being examined and by, in general, what types of individuals.” Introducing a theme that recurred throughout these discussions, one participant stated that the legitimacy of proposed uses of study data “depends on how [the study subject] understood what was going to be done with that information.”

Participants placed less emphasis on the disclosure of potential risks, the main category of which they identified as breach of privacy. They were skeptical of promises that subjects’ personal information would be protected, citing news reports of “stolen laptops” and unauthorized access to credit-card databases or banking records. Participants also noted that a person’s study participation could pose a risk to her descendants. One participant, who had told the group that he had a child with autism, said,

“My concerns [about participating] are probably my son’s. I just don’t see anything really being figured out in my lifetime, where I’m getting spammed [with marketing from commercial interests] based on future diseases I may have. But I am sort of throwing out, you know, everybody that comes after me is linked too. So it’s definitely kind of a heavy consideration.”

Tiered consent: offering categorical options

With respect to the approach researchers should use in obtaining informed consent from study subjects, participants suggested – without prompting from the facilitators – a model that would allow study subjects to give permission for different study elements independently, sometimes referred to as “tiered consent.” The more different directions future investigations could take, the more some participants felt it would be important for subjects to have an opportunity to weigh in. One participant remarked, “I’m much more inclined to do something which is very specific and not go any further with it. To me, this is just getting so complex. I mean, I feel like – I’m a simple person, and this is way too complex for me … It just seems like it’s so complex that it can break down.”

Some participants thought tiered consent may be appropriate when researchers want to be able to use data or samples for purposes other than those contained in the aims of the primary study. For example, subjects enrolled in a diabetes study could choose whether to permit no additional use of their data; use of their data in diabetes research only; or use in any other health-related research. One participant introduced the idea this way: “Maybe you have a two-step process, where it’s either ‘I consent to this [particular study],’ or you have some super-waiver [that grants consent for any other study]. And some people may choose to [sign the broader version], but I wouldn’t want to change the game after you’ve already signed up for it.” Another stated, “I would almost want to see, on my initial consent form – it could get complicated, but – ‘Are you ok with this specific study that we are going to do? Sign here.’ And ‘If you’re ok with us sharing [data with other researchers], sign here as well.’ And ‘If you’re ok with us [studying] hypertension [in addition to diabetes]…’ I think I might want to agree to each thing.”

If researchers wish to share data with outside collaborators or submit data to a repository such as dbGaP, participants suggested that the consent form could give study subjects the ability to allow open sharing vs. none, or to prohibit sharing with certain kinds of organizations, such as for-profit corporate entities. Many participants expressed distrust of for-profits and pharmaceutical manufacturers. Tiered consent was also proposed for the inclusion of specific elements from the medical record, such as., whether information about reproductive health, sexual history, substance abuse, or mental illness could be shared. One participant remarked that tiered consent could have the unintended effect of limiting subjects’ participation – “You might end up alerting people to things they hadn’t thought about, and make them less likely to do it, because they hadn’t considered some of that information before” – but went on to say that enabling more informed choices was nevertheless a good thing.

Likewise, participants saw tiered consent as an appropriate approach to ascertaining study subjects’ desires regarding access to their individual research findings: “Couldn’t there be a box that you’d check, ‘I want to know,’ or ‘I don’t want to know?’” Although most participants indicated that they would wish to receive information about themselves resulting from their study participation, others were ambivalent, particularly with regard to findings for which no effective medical intervention is currently available (e.g., an increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease).

Open consent: broad permissions at the outset

Views were more mixed with respect to open consent., in which participants would be asked to give general permission for undefined future research. Very few participants were completely comfortable with this form of consent, despite the fact that they understood that association studies are strongest when comprehensive data are available and unanticipated research questions can be pursued:

“I think of the weird thing about [dental] plaque and how plaque, they’re finding, relates to heart attacks and atherosclerosis and stuff. And it’s like, who would ever have thought there was a link between that …. I don’t know. I just think there are things that seem unrelated that could relate. But then you get into this kind of fishy weirdness of, ‘Why are they testing this if I signed up for that?’”

Regardless of the scientific value of comprehensive data collection, some participants said that they would be unwilling to sign a broad consent: “I probably wouldn’t sign it, because I don’t know what ‘anything’ means.”

If the initial consent process clearly stated that the data could be used for anything, participants took a caveat emptor view:

“The onus is on the individual. You have to assess those risks at the time. You know, how did I know when I bought a car that my car was going to be a total lemon and break down at 55,000 miles when the warranty expired at 50,000 miles? That’s just – you take certain risks if you want to participate in a study.”

Another participant commented:

“If [subjects] originally sign a consent form for one study, then you can’t share that information beyond that study unless you warn the person, because that’s not what they signed up for in the first place. But if [subjects] signed up knowing that it could be used for anything – if you can get people to do that – then that would be a different scenario …. If I was signing a broad document like that, I would understand that I was basically signing a blanket, and it would just be going wherever, and I’d have no control.”

Although participants considered such an approach technically acceptable, they believed that few prospective subjects would agree to this kind of wide-open future use.

Participants also commented on possible risk-management implications of open consent approaches:

“If I [signed a broad consent], I would know [that I had no control over my study data]. I don’t know if everybody else would know that, and maybe [the institution] would be exposing themselves to a lot of problems in the future if in fact there was a problem, because that’s when people come back and say, ‘Well, I didn’t understand what I was signing!’.”

Even if broad consent had been obtained up front, some participants doubted that it would protect the institution from legal liability or negative publicity if something went wrong.

There appeared to be a difference in perceptions of informed consent, particularly broad consent, between the eldest group (participants aged 50 and older) and the two younger groups (aged 18 – 49, collectively). Older participants tended to view the informed consent process as one part of an ongoing trust relationship between the research subject and the researchers, with the informed consent form standing as proof of the researchers’ intentions toward subjects, rather than an authoritative document describing the allowable parameters of the study. They often spoke in terms of the relationship between the subject and the researcher, describing the consent process as a matter of “common courtesy.” One participant, talking about how study subjects can receive assurance that nothing untoward is being done with their study data, said, “It all comes down to a matter of trust.” Participants in the older groups were more likely to find broad consent acceptable, and to consider IRB review of future studies sufficient protection of subjects’ interests. In contrast, younger participants were more likely to construe the consent form in a literal way, such that activities not explicitly spelled out in the consent form could not be carried out (legally or ethically), even if human subjects review were conducted. One participant in the younger group used the word “contract” in speaking about the consent form: asked whether it would be acceptable for researchers to use GWAS data to study a non-health-related topic, such as ancestry, he said, “Well, if that wasn’t part of the contract, I would have a problem with that.”

Re-consent: when additional permission is appropriate

Almost all participants believed that researchers should seek study subjects’ consent prior to implementing a substantive change in study procedures – for example, if data were to be used to study a different disease, or if data were to be provided to a for-profit entity that had not been named in the original consent. One participant commented that if researchers wanted to submit study data to dbGaP:

“The key would be that they would come and ask for your permission, If you signed up for something and it was done, then ask for permission [for sharing], and if you give your permission, then yes. But without asking, I don’t think so. I think that’s a huge ethical breach.”

Another commented, “I think most people would say yes, but I think they deserve to be asked.”

Participants articulated a number of different rationales for this position. In some cases, the desire for re-consent was grounded in the right of the individual participant to choose what could be done with her information. For example, participants who found certain kinds of research morally objectionable (e.g., research seeking to connect race with intelligence or alcoholism) wanted to be able to opt out of such studies. Participants said that investigators should not presume that a person who is willing to take part in one study would naturally be willing to sign up for another: for example, an individual who signs up for a GWAS on breast cancer because a friend had the disease may not be equally willing to contribute to studies that do not “hit the heartstring” for her. Participants also commented that, given that study data submitted to dbGaP would remain accessible indefinitely, changes could very easily occur over time – in subjects’ personal values, their health status, the state of scientific knowledge, or governance structures and policy – that might cause them to weigh their participation differently. For this reason, they wanted researchers to check in with study subjects regarding specific changes as they came up. Another set of arguments in favor of re-consent, more commonly articulated among participants in the over-50 sessions, was rooted in a sense of the researchers’ regard for the participants and their contribution. Asking for additional permissions was perceived as respectful, “courteous,” and “the right thing to do”; it was also seen as a way of keeping research subjects involved in the ongoing activities of the study.

Participants also articulated pragmatic reasons for seeking re-consent. If re-consent were not obtained, the objections of a single disaffected study participant could result in a lawsuit or negative publicity for the researcher and the institution. Given that possibility, some participants thought it would be “better to be safe than sorry.” A few participants were of the opinion that a single, clear policy (i.e., always ask for permission) would obviate the effort and expense involved in keeping track of individual study subjects’ wishes.

Participants’ preference for re-consent, though strong, was not absolute: there were situations in which participants felt that it would be unnecessary and inappropriate for researchers to seek additional permissions. For example, participants thought that re-consent was not needed if the researcher wanted to study a different gene variant from the one(s) named in the original consent, with study goals otherwise the same. The change was immaterial, from their point of view, and the re-consent process would be an unreasonable expense for the research institution. In addition, some felt that such contact could be burdensome to research subjects: “In this day and age, you’ve already got millions of pieces of paper. You don’t need another one!”

Although participants believed that most study subjects would likely grant re-consent, they wanted researchers to respect the preferences of the rare individual who would not wish to have his information used in a way that had not been described in the initial consent process.

“I don’t think that people who do consent to a [genetic study] would have any problem at all helping the greater study. I don’t think the majority of them would. However, there might be personal opinions or personal experiences where they’d say, ‘Well, I did want to help with this initial one, but this secondary one, I don’t feel comfortable with’ … I don’t know if it would be right to [use the data without re-consent].”

As another participant put it,

“I think everybody is going to have a different line. That’s why I would want to see it specified. Basically, I know I would say yes to everything, but I would feel weird if something had been done that I hadn’t said yes to – even though I would have said yes if I had been asked. I just want to be asked.”

DISCUSSION

This study provides new insights into prospective research participants’ views about the possible risks and harms of participation in genome-scale studies and what the informed consent process for such research should look like in the light of such risks. Many of the possible risks to study subjects identified by our focus group participants echo those described in the expert literature, with privacy considerations at the top of the list. However, this study suggests that prospective study subjects may weigh the likelihood of harm and the severity of potential injury differently from regulators or human-subjects professionals and, indeed, from each other. In the interest of subject protection, great emphasis has been placed on providing complete information about the potential negative consequences to individual subjects. However, our participants considered information about study purpose, potential outcomes of the study, and how and by whom study data could be used to be at least as important as information about risks and possible harms.

With respect to the form of the informed consent process, our findings provide additional support to several previously published empirical investigations. Our results are consistent with those reported by McGuire and colleagues, in which focus group participants (aged 18–70, mostly white, with less formal education than our study population) were found to prefer a tiered approach to consent for wide data-sharing but were likely to consent to narrower sharing when given the choice (McGuire et al. 2008). Findings from this study are also consistent with Beskow and colleagues’ results regarding variation in informational needs and interests among study participants reviewing an online consent form (Beskow et al. 2010).

Our findings are somewhat discordant with a study reported by Simon and colleagues, in which 54% of focus group participants and 41% of survey respondents indicated a preference for broad consent (Simon et al. 2011). However, that study also identified the concerns voiced by our participants about limited informational content and lack of individual control; and the authors note that another interpretation of their data – in which participants could be construed to favor choice-promoting approaches over approaches that offer less individual control, such as broad consent – is possible. Consistent with our results, Simon and colleagues also found that participants 55 and older were more likely to favor broad consent.

Participants in our study valued “being asked” about new uses of existing study data, including sharing with other researchers and use in other investigations. Contrary to an earlier survey study with older adults (Wendler and Emanuel 2002) but consistent with another recent study with Group Health research participants similar to the Wendler and Emanuel population (Ludman et al. 2010), our findings suggest that the majority of these study subjects felt that re-consent for the use of existing, de-identified study data is appropriate and would likely grant re-consent for additional uses of existing study data. Efforts to secure such additional permissions still face practical hurdles, including the time, effort, and cost involved in locating study subjects (or, in some states, next of kin for deceased subjects), providing information, and securing written consent. However, our results indicate that such efforts may be a worthwhile investment, particularly for institutions that seek to build ongoing trust relationships with their study populations.

Some limitations to the generalizability of our findings should be noted. Our participants are not a nationally representative sample in terms of race/ethnicity, educational level, or household income: most participants were white, well-educated, and economically secure. In addition, individuals who are unwilling to participate in research, or who hold strongly negative views with respect to genetic research, may have been less likely to take part in these focus groups. However, given that the vast majority of participants in genetic research are of European descent (Need and Goldstein 2009) and that little is known about the propensity of different populations and subgroups to take part in genome-scale research (Sterling, Henderson, and Corbie-Smith 2006), our sample may be fairly representative of the population most likely to volunteer for GWAS and similar studies.

The results of this study lead us to a few recommendations. Consent forms should explain – not merely state – the purpose of the study, so that participants can gauge their own interest in the problem that the research aims to address. While the consent process should describe as clearly as possible the scope of the planned investigation, investigators should avoid providing overly specific parameters that do not affect risks or benefits (e.g., the names of specific genetic variants).

It is still unclear how the informed consent process should account for risks and harms in genome-scale research. Possible risks to subjects in genome-scale research are difficult to predict and are likely to change as science advances; known harms are generally regarded as unlikely by participants in this study as well as genetic researchers (Edwards et al. 2011) and IRB professionals (Lemke et al. 2010). The consent process should of course describe known risks and potential risks, and outline possible harms; it should also describe the measures taken to mitigate them (Lunshof et al. 2008). Researchers and institutions should not make promises that they cannot keep. In particular, the consent process should not guarantee the protection of subjects’ privacy and confidentiality, though assurances should be provided that the researchers will do their best to protect participants’ interests. If the likelihood of a given harm is unknown, this should be stated explicitly. The consent process should help subjects understand that this field is moving rapidly, and that the potential risks to individuals are therefore subject to change. More investigation is needed to identify the best ways to explain a situation in which some risks are unknown, while other risks are known but are unlikely to result in harm.

We believe that further research is needed to determine how best to facilitate ongoing participant control over specific elements of research (Trinidad et al. 2011); however, when the scope of a study has changed materially, we recommend that additional permissions be sought when practicable. These efforts can be costly and time-consuming, and their adoption will therefore require greater flexibility on the part of funders and researchers in terms of funding parameters and project timelines.

Participants in these discussions expressed a great deal of interest in learning about the progress of research. They may not be representative in this respect – they did agree to take part in a two-hour discussion about research participation – but investigations aimed at developing low-cost tools for keeping interested study subjects informed could be worthwhile in terms of increasing trust and engagement in research. In this area, researchers and human-subjects professionals may be able to learn from marketing scholarship on customer loyalty and “stickiness,” including strategies that seek to leverage each encounter as an invitation to further engagement (Holland and Menzel Baker 2001).

Throughout these discussions, we were struck by a pervasive theme: while participants were supportive of genomic research and generally willing to participate in a very broad range of study types, they did not have a laissez-faire attitude about consent. On the contrary, the large majority of these participants were interested in understanding study goals, finding out about what might be learned along the way, and being kept abreast of how their contributions may be used to advance knowledge. The informed consent process remains an important part of the picture, but the days of consent as a one-time exchange of data and permission are drawing to a close (Mascalzoni et al. 2008) – not only because the science is a moving target, but also because a growing body of data shows that participants want to be kept informed over time.

Figure 2.

Setting the Stage – Intro to GWAS

Table 2.

Key findings

|

Acknowledgments

The eMERGE Network was initiated and funded by NHGRI, in conjunction with additional funding from NIGMS through grant no. U01-HG-004610. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Group Health Cooperative members who took part in these discussions. We thank Kelly Ehrlich, Darlene White, Cheryl Wiese, and Dorothy Oliver for their help in carrying out the focus groups.

Contributor Information

Susan Brown Trinidad, University of Washington.

Stephanie M. Fullerton, University of Washington

Julie M. Bares, University of Washington

Gail P. Jarvik, University of Washington

Eric B. Larson, Group Health Research Institute

Wylie Burke, University of Washington.

References

- Beskow LM, Friedman JY, Hardy NC, Lin L, Weinfurt KP. Simplifying informed consent for biorepositories: stakeholder perspectives. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010;12(9):567–72. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ead64d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KL, Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Lewis SM, Starks H, Quinn Griffin MT, Wiesner GL. Attitudes toward genetic research review: Results from a survey of human genetics researchers. Public Health Genomics. 2011 doi: 10.1159/000324931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greely HT. The uneasy ethical and legal underpinnings of large-scale genomic biobanks. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2007;8:343–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland Jonna, Baker Stacey Menzel. Customer participation in creating site brandloyalty. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 2001;15(4):34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke AA, Trinidad SB, Edwards KL, Starks H, Wiesner GL. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a national survey of professionals involved in human subjects protection. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics : JERHRE. 2010;5(1):83–91. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman EJ, Fullerton SM, Spangler L, Trinidad SB, Fujii MM, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Glad you asked: participants’ opinions of re-consent for dbGaP data submission. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics : JERHRE. 2010;5(3):9–16. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunshof JE, Chadwick R, Vorhaus DB, Church GM. From genetic privacy to open consent. Nature reviews Genetics. 2008;9(5):406–11. doi: 10.1038/nrg2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, Hao L, Kiang A, Paschall J, Phan L, Popova N, Pretel S, Ziyabari L, Lee M, Shao Y, Wang ZY, Sirotkin K, Ward M, Kholodov M, Zbicz K, Beck J, Kimelman M, Shevelev S, Preuss D, Yaschenko E, Graeff A, Ostell J, Sherry ST. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(10):1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascalzoni Deborah, Hicks Andrew, Pramstaller Peter, Wjst Matthias. Informed consent in the genomics era. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9):e192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschke KJ. Wanted: human biospecimens. The Hastings Center report. 2010;40(5):21–3. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2010.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AL, Gibbs RA. No longer de-identified. Science. 2006;312(5772):370–371. doi: 10.1126/science.1125339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AL, Hamilton JA, Lunstroth R, McCullough LB, Goldman A. DNA data sharing: research participants’ perspectives. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2008;10(1):46–53. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f1e00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Final NIH Statement on Sharing Research Data. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Policy for Sharing of Data Obtained in NIH-Supported or Conducted Genome-Wide Association Studies. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Need AC, Goldstein DB. Next generation disparities in human genomics:concerns and remedies. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2009;25(11):489–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm P. Broken promises of privacy: Responding to the surprising failure of anonymization. UCLA Law Review. 2010;57(6):1701–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein MA. Is deidentification sufficient to protect health privacy in research? The American journal of bioethics : AJOB. 2010;10(9):3–11. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2010.494215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CM, L’Heureux J, Murray JC, Winokur P, Weiner G, Newbury E, Shinkunas L, Zimmerman B. Active choice but not too active: Public perspectives on biobank consent models. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2011 doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821d2f88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling R, Henderson GE, Corbie-Smith G. Public willingness to participate in and public opinions about genetic variation research: a review of the literature. American journal of public health. 2006;96(11):1971–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. Pharmacogenomics and bioinformatics:PharmGKB. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11(4):501–5. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Genomic research and wide data sharing: views of prospective participants. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010;12(8):486–95. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e38f9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Ludman EJ, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Research ethics. Research practice and participant preferences: the growing gulf. Science. 2011;331(6015):287–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1199000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Emanuel E. The debate over research on stored biological samples: what do sources think? Archives of internal medicine. 2002;162(13):1457–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.13.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]