Abstract

Liver stem cells are thought to preside in bile ducts and the canals of Hering. They extend into the liver parenchyma at a time when normal liver cell proliferation is suppressed and liver regeneration is stimulated. In the present study 69 liver biopsies and surgically excised liver tumors were studied for the presence of liver stem cells. It was found that human cirrhotic livers and hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) frequently exhibited isolated single scattered hepatocyte stem cells within the liver parenchyma rather than in the portal tract, bile duct or the canal of Hering. These cells expressed liver stem cell markers. HCCs also contained isolated tumor cell which expressed the same stem cell markers. The markers used were GST-P, OV-6, CK-19, Oct-3/4 and FAT10. They were identified by immunofluorescent antibody staining. HGF, EGF, CK19, AIR, H19, Nanog, Oct-3/4 and FAT10 were identified by RNA-FISH. H19 is a non-coding RNA, which is expressed in most HCCs. Results: Immunohistochemistry and RNA-FISH performed on human livers identified isolated stem cells in liver parenchyma as follows: Stem cells identified by immunohistochemical markers (OV-6 and GST-P) and RNA-FISH markers (HGF, EGF, CK19 and H19) were found scattered in the liver parenchyma of cirrhotic livers and within hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs). Precirrhotic ASH or NASH all stained negative for these stem cells. In HCCs, 13 out of 15 had stem cells located within the tumor (78%). In cirrhotic livers, 12 out of 28 (37%) had liver parenchymal stem cells present. In one case of stage 3 precirrhosis, stem cells were also found. Double staining for the markers showed colocalization of the markers in stem cells. Stem cells were found in 33% of HBV, 47% of HCV, 25% of alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and 17% of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). The frequency of stem cells found in the different disease categories correlates with the frequency of HCC occurring in these different diseases.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor (EGF), Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), Glutathione S-transferase placental (GST-P), O. volvulus 6 (OV-6), AIR (antisense Igf2r)

Introduction

The liver plays a central role in metabolic homeostasis, as it is responsible for the metabolism, synthesis, storage and redistribution of nutrients, carbohydrates, fats and vitamins (Saxema et al., 2003). Importantly, it is the main detoxifying organ of the body, which removes wastes and xenobiotics by metabolic conversion and biliary excretion. The main cell type of the liver that carries out most of these functions is the parenchymal cell, or hepatocyte, which makes up ~80% of cells, in the liver. Although adult hepatocytes are long lived and normally have a low rate of cell division, they maintain the ability to proliferate in response to toxic injury and infection (Cantz et al., 2008). The amazing regenerative capacity of the liver is most clearly shown by the two-thirds partial-hepatectomy model in rodents, which was pioneered by Higgins and Anderson in 1931 (Higgins and Anderson, 1931). Cell division is rarely seen in hepatocytes in the normal adult liver, as these cells are in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (Michalopoulos and DeFrances, 1997; Taub et al., 1999). The degree of replication of these cells correlates with the degree of inflammation and fibrosis in diseases such as chronic hepatitis, hemochromatosis, alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (Libbrecht et al., 2000; Lowes et al., 1999). However, after partial hepatectomy approximately 95% of hepatic cells, which are normally quiescent, rapidly re-enter the cell cycle. The onset of DNA synthesis is well synchronized in hepatocytes, beginning in cells that surround the portal vein of the liver lobule and proceeding towards the central vein (Minuk, 2003). Many growth factors are involved in the regeneration of the liver: hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (Nishino et al., 2008), epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Natarajan et al., 2007), transforming growth factors (TGFs) (Weymann et al., 2009), insulin (Stefano et al., 2006), glucagon (Kothary et al., 1995) and insulin like growth factor (Sanz et al., 2005).

In animal models, in which hepatocytes are directly damaged and thereby induced to undergo necrosis. His resembles simulates growth-factor- and cytokine-mediated pathway up regulation seen after partial hepatectomy (Dabeva et al., 1993; Dabeva and Shafritz, 1993). Proliferation of hepatocytes is also involved in the liver regeneration that occurs after massive hepatocytic necrosis or apoptosis that is induced by hepatic toxins such as CCl4 (Fausto, 1999).

Human hepatic stem cells rather than quiescent hepatocytes are responsible for regeneration when cirrhosis develops, in order to compensate for the regenerative response to liver injury due to the up regulation of p21 in the cirrhotic liver (Kato et al., 2005). P21 inhibits cell cycling at the G2 stage of mitosis in the cirrhotic liver (Ridley et al., 1988). Identification of liver stem cells promises new therapeutic treatments for a wide range of liver pathological conditions (e.g. cirrhosis, hepatocarcinogenesis). It has been speculated that human stem cells could be the precursors of HCC as well as cholangiocarcinomas, which also drive HCC cellular growth (Theise et al., 1999). Indeed, several studies showed that HCC expressed markers of stem cells such as OV6, A6, OV1, AFP, CK7 and CK19 (Bottinger et al., 1997; Chiba et al., 2006; Herrera et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2004; Roskams et al., 1998; Roskams et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2003). Other markers that can be used to identify stem cells are: CD34+, Thy-1+, c-Kit+ and Flt3+ (Burke et al., 2007). HCCs expressing these markers are likely to have significantly more negative prognosis and a higher recurrence after surgical resection and liver transplantation because of the resistance of stem cells to chemotherapy (Sell, 2008).

In this study, we used stem cell marker (OV-6) to identify these cells in the biopsies of different patients (Mishra et al., 2009). GST-P was also used to identify these cells, but GST-P is a marker that identifies oval cells also (Hepatic progenitor cells) in the damaged mammalian liver (Alison et al., 2009). Oval cells are defined as small cells with an oval nucleus and scanty cytoplasm and are considered to be progenitor cells with the ability to differentiate into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes (Farber, 1956; Rountree et al., 2007). They are said to proliferate when the cell cycle of normal hepatocytes is suppressed by up regulation of p21. They are located in the portal tract (Roskams, 2006). In addition, we used two new stem cell markers (EGF and HGF). There was a positive correlation between the causes of the chronic liver disease studied and the frequency of the stem cells found in the cases.

Materials and methods

Immunofluorescent staining

Liver sections were stained with rabbit anti-ubiquitin polyclonal antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Antibody binding was detected with Texas-Red labeled and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson, West Grove, PA). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. The slides were examined using a Nikon-400 fluorescent microscope with a FITC, Rhodamine and a triple color band cube to detect simultaneously FITC, Texas Red and DAPI staining. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Laica fluorescent microscope.

Amplification and cloning of human and mouse probes

The probes were amplified by using Phusion™ Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes Inc., Woburn, MA). The conditions for PCR are: 98 °C 30 s, 98 °C 30 s, 60 °C 30 s, 72 °C 30 s (40 cycles), 72 °C 5mn. The PCR product is separated in a 1% Agarose gel using the NucleoSpin Extract II (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA). The purified PCR products are cloned in the pGMET vectors, overnight at 16 °C, following the instructions of the company (Promega, Madison, WI). JM109 bacteria are transformed with the ligation product (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Positive clones are selected with EcoRI digestion. All the clones are sequenced. Sequence of the primers used to amplify the probe:

Hybridization in situ of RNA (RNA-FISH)

The slides were placed in Xylene 10 mn, in 1:1 Xylene/EtOH 10 mn and finally in 100% EtOH 10 mn (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). They were washed in PBS and placed in digestion buffer (PBS+SDS 0.05%+Proteinase K 10 μg/ml) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), at room temperature for 10mn. They were then fixed in cold fresh-made 4% paraformaldehyde, at 4 °C, 20 mn. They were washed in PBS and placed in 0.1 M PBS/Tween20 0.1%, for 30 mn. They were then placed in the prehybridization buffer (1:1 Formamide/5× SSC) for 2 h at 65 °C. The probe was made using a Fluorescein High-Prime, and using Tetramethyl-rhodamine-5-dUTP, following the instructions of the company (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The probe was incubated with the slides at 65 °C, 16 h. The slides were then washed in 2× SSC, for 30 mn at RT, 1 h at 65 °C in 2× SSC, 1 h at 65 °C with 0.2× SSC, 10 mn at PBS/Tween20 65 °C and 10 mn with PBS/Tween20 at room temperature.

Results

Stains for twelve stem cell markers (Stem Cells/Progenitors cells SCPs) were performed either by RNA-FISH or immunohistochemistry. The control livers stained negative for the stem cells/progenitor cells (SCPs) except in one case in which one parenchyma liver cell stained positive for OV-6 and GST-P. Tables 2–7 give the staining results. The results are broken down as to age, sex, HBV+, HCV+, HCC+, cirrhosis and Mallory–Denk Body formation. Each stain result was broken down to indicate whether the positive cells were present in cirrhosis, HCC or others (non cirrhotic and non HCC).

Table 2.

Summary of the cases positive with hepatitis B virus (HBV).

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | rrhos | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

Ubd |

Nanog |

Oct4 |

Oct3 |

CD133 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | ||||||||

| 44 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | M | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | M | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 69 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 7 Summary of the cases positive with non-alcoholic steaotehepatitis (NASH).

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | Cirrhosis | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | ||||||||

| 14 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 1 showed that of 18 HCCs, there were 14 cases in which SCPs were identified by one or more stains (78%). The high frequency of stem cells in HCC influenced the frequency of stem cells found in the various liver diseases studied. That is at caused the frequency to be higher when the HCC was also present (Tables 2–7).

Table 1.

| Antibodies | Company |

|---|---|

| Goat Anti CK19 | Abcam, Cambridge, MA |

| Rabbit alpha GST-P | Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA |

| Rabbit anti Oct3/4 | Abgen, San Diego, CA |

| Mouse anti OV-6 | R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN |

The high frequency influenced the frequency in stem cells form in the other liver diseases sampled where the frequency of HCC was high (Tables 2–7).

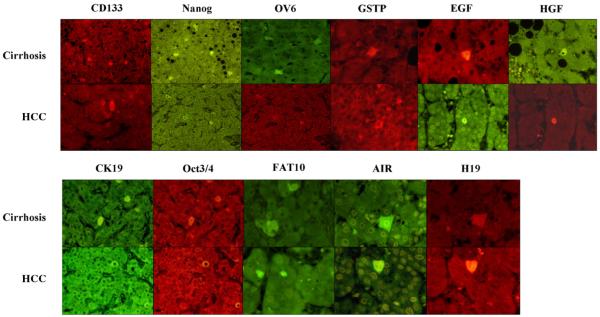

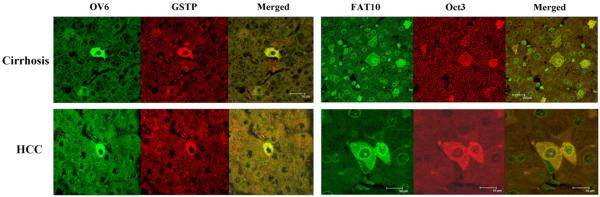

The frequency of positive stem cell markers in the various diseases roughly correlated with the relatively frequency of HCC that develops in the clinical setting i.e. HCV 47%, HBV 35%, cirrhosis 33%, ASH 25%, NASH 16.5% (Table 8). The positive stem cell markers found in cirrhosis and HCCs are illustrated in Fig. 1. All of the RNA-FISH and immunostaining that were positive in cirrhosis and HCCs were double stained which when viewed by confocal microscopy showed that the same cells stained positive for both markers and when merged appeared yellow indicating that the two proteins or mRNAs colocalized (Fig. 2). The individual stem cells were single in the liver parenchyma with few exceptions and had abundant cytoplasm and were polyhedral shaped fitting into liver cell cords and tumor areas period. They resemble the normal liver cells and tumor cells. These cells were not identified as different morphogically from their neighboring cells.

Table 8.

Summary of the cases analyzed for the stem cells.

| Liver disease | # of cases | # of cases with at least 1 positive stem cell marker(s) |

% of cases with at least 1 positive stem cell marker(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | 18 | 14 | 78 |

| Hepatitis C | 17 | 8 | 47 |

| Hepatitis B | 17 | 6 | 35 |

| Cirrhosis | 35 | 13 | 37 |

| ASH | 12 | 3 | 25 |

| NASH | 6 | 1 | 17 |

Fig. 1.

EGF, HGF, CD133, FAT10, AIR and H19 were done by RNA-FISH. Oct4, CK19, GST-P, OV6 and Nanog were done by immunohistochemistry.

Fig. 2.

OV6 and GST-P were done by immunohistochemistry. FAT10 and Oct3 were done by RNA-FISH.

Discussion

The stem cells identified by immunostaining or RNA-FISH were commonly found in HCCs. The frequency, 78% is higher than previously reported by Thorgeirsson and Grisham (Thorgeirsson and Grisham, 2006). These stem cells, which were positive for a host of different stem cell markers, were not located in the portal tracts, bile ducts or canals of Hering. They have been characterized as oval cells or hepatic progenitors cells in animal and human chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis (Theise et al., 1999; Roskams et al., 1998; Roskams et al., 2004; Chiba et al., 2006; Mishra et al., 2009). Instead, they were located and scattered as single cells in the liver parenchyma and in tumors with no relationship to the portal tracts in this present study. They had the morphology of their neighboring hepatocytes in both cirrhosis and in HCCs. They stained positive for CD133 in both HCCs and cirrhosis as described by others (Alison et al., 2009). These results were presented in part in an abstract (Oliva et al., 2009).

| Human primers | |||

| EGF | NM_001963 | Forward | GTAGCCAGCTCTGCGTTCCT |

| NM_001963 | Reverse | CTTTCTCGCTGGGAACCATC | |

| HGF | NM_001010934 | Forward | AGGGATCACTGGAAGCTTGA |

| NM_001010934 | Reverse | TAGTCCCCCTCCCCAAATAC | |

| CK19 | NC_000017. | Forward | AAGGAGGGAGGCTTGGTAAA |

| NC_000017 | Reverse | GGTCTGTGGGTCTGGGTCTA | |

| Oct3/4 | NM_203289.3 | Forward | GGTATTCAGCCAAACGACCA |

| NM_203289.3 | Reverse | CACACTCGGACCACATCCTT | |

| Nanog | NM_024865.2 | Forward | GTGATTTGTGGGCCTGAAGA |

| NM_024865.2 | Reverse | ACACAGCTGGGTGGAAGAGA | |

| Sox2 | NM_003106.2 | Forward | GACAGTTACGCGCACATGAA |

| NM_003106.2 | Reverse | TAGGTCTGCGAGCTGGTCAT | |

| FAT10 | NM_006398 | Forward | AATGCTTCCTGCCTCTGTGT |

| NM_006398 | Reverse | TTTCACTTGTGCCACTGAGC | |

| H19 | NR_002196 | Forward | CCTCATCAGCCCAACATCAA |

| NR_002196 | Reverse | GGGGAAACAGAGTCGTGGAG | |

| AIR | GQ166646 | Forward | AAGTCAGGATCACCAGCCTTT |

| GQ166646 | Reverse | TACACTCACTAGACCCACCCG |

Table 3.

Summary of the cases positive with hepatitis C virus (HCV).

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | Cirrhosis | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

Ubd |

Nanog |

Oct4 |

Oct3 |

CD133 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | ||||||||

| 59 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | M | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 42 | F | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 69 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 4.

Summary of the cases with cirrhosis.

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | Cirrhosis | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

Ubd |

Nanog |

Oct4 |

Oct3 |

CD133 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | ||||||||

| 64 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 75 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65 | M | ? | ? | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | M | ? | ? | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 61 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 61 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | F | ? | ? | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 76 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 69 | F | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5.

Summary of the cases positive with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCCs).

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | Cirrhosis | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

Ubd |

Nanog |

Oct4 |

Oct3 |

CD133 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | ||||||||

| 64 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 75 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65 | M | ? | ? | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 83 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | M | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | M | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | M | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | F | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 67 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 6.

Summary of the cases positive with alcoholic steaotehepatitis (ASH).

| Age | Sex | HBV | HCV | Cirrhosis | HCC | NASH | ASH | MDB |

OV6 |

GST-P |

HGF |

EGF |

CK19 |

H19 |

AIR |

Ubd |

Nanog |

Oct4 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | C | T | O | ||||||||

| 58 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | M | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | |||||||||||||||

| 61 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | M | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | F | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 54 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | F | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIH/NIAAA grant 8116 and the Alcohol Center Grant on Liver and Pancreas P50-011999, including the morphology core.

References

- Alison MR, et al. Stem cells in liver regeneration, fibrosis and cancer: the good, the bad and the ugly. J. Pathol. 2009;217:282–298. doi: 10.1002/path.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottinger EP, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor beta receptor show enhanced tumorigenesis in the mammary gland and lung in response to the carcinogen 7, 12-dimethylbenz-[a]-anthracene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5564–5570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke ZD, et al. Stem cells in the adult pancreas and liver. Biochem. J. 2007;404:169–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantz T, et al. Stem cells in liver regeneration and therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;331:271–282. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0483-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44:240–251. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabeva MD, et al. Models for hepatic progenitor cell activation. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1993;204:242–252. doi: 10.3181/00379727-204-43660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabeva MD, Shafritz DA. Activation, proliferation, and differentiation of progenitor cells into hepatocytes in the D-galactosamine model of liver regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 1993;143:1606–1620. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber E. Similarities in the sequence of early histological changes induced in the liver of the rat by ethionine, 2-acetylamino-fluorene, and 3′-methyl-4-dimethylaminoazobenzene. Cancer Res. 1956;16:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto N. Lessons from genetically engineered animal models. V. Knocking out genes to study liver regeneration: present and future. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G917–G921. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera MB, et al. Isolation and characterization of a stem cell population from adult human liver. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2840–2850. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GM, Anderson RM. Experimental pathology of the liver. I restoration of the liver of the white rat following partial surgical removal. Arch. Pathol. 1931;12:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, et al. Relationship between expression of cyclin D1 and impaired liver regeneration observed in fibrotic or cirrhotic rats. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;20:1198–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, et al. Primary liver carcinoma of intermediate (hepatocyte–cholangiocyte) phenotype. J. Hepatol. 2004;40:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothary PC, et al. Preferential suppression of insulin-stimulated proliferation of cultured hepatocytes by somatostatin: evidence for receptor-mediated growth regulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 1995;59:258–265. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht L, et al. The immunohistochemical phenotype of dysplastic foci in human liver: correlation with putative progenitor cells. J. Hepatol. 2000;33:76–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowes KN, et al. Oval cell numbers in human chronic liver diseases are directly related to disease severity. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;154:537–541. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos GK, DeFrances MC. Liver regeneration. Science. 1997;276:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuk GY. Hepatic regeneration: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2003;17:418–424. doi: 10.1155/2003/615403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra L, et al. Liver stem cells and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;49:318–329. doi: 10.1002/hep.22704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan A, et al. The EGF receptor is required for efficient liver regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:17081–17086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704126104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino M, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor improves survival after partial hepatectomy in cirrhotic rats suppressing apoptosis of hepatocytes. Surgery. 2008;144:374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J, et al. Heretofore unidentified stem cells in human liver disease. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20 Supplement Abstract 1222. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, et al. Ras-mediated cell cycle arrest is altered by nuclear oncogenes to induce Schwann cell transformation. EMBO J. 1988;7:1635–1645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskams T. Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:3818–3822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskams T, et al. Hepatic OV-6 expression in human liver disease and rat experiments: evidence for hepatic progenitor cells in man. J. Hepatol. 1998;29:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskams TA, et al. Nomenclature of the finer branches of the biliary tree: canals, ductules, and ductular reactions in human livers. Hepatology. 2004;39:1739–1745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree CB, et al. A CD133-expressing murine liver oval cell population with bilineage potential. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2419–2429. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz S, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor I by activated hepatic stellate cells reduces fibrogenesis and enhances regeneration after liver injury. Gut. 2005;54:134–141. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxema R, et al. Hepatology. Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver disease. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. Alpha-fetoprotein, stem cells and cancer: how study of the production of alpha-fetoprotein during chemical hepatocarcinogenesis led to reaffirmation of the stem cell theory of cancer. Tumour Biol. 2008;29:161–180. doi: 10.1159/000143402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano JT, et al. Increased hepatic expression of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor in chronic hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3821–3828. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i24.3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub R, et al. Transcriptional regulatory signals define cytokine-dependent and -independent pathways in liver regeneration. Semin. Liver Dis. 1999;19:117–127. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theise ND, et al. The canals of Hering and hepatic stem cells in humans. Hepatology. 1999;30:1425–1433. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Hematopoietic cells as hepatocyte stem cells: a critical review of the evidence. Hepatology. 2006;43:2–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weymann A, et al. p21 is required for dextrose-mediated inhibition of mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2006;50:207–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.22979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao JC, et al. Small epithelial cells in human liver cirrhosis exhibit features of hepatic stem-like cells: immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and immunoelectron microscopic findings. Histopathology. 2003;42:141–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]