Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests that human γδ T cells act as non-classical T cells and contribute to both innate and adaptive immune responses in infections. Vγ2 Vδ2 T (also termed Vγ9 Vδ2 T) cells exist only in primates, and in humans represent a dominant circulating γδ T-cell subset. Primate Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells are the only γδ T cell subset capable of recognizing microbial phosphoantigen. Since nonhuman primate Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells resemble their human counterparts, in-depth studies have been undertaken in macaques to understand the biology and function of human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. This article reviews the recent progress for immune biology of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in infections.

Keywords: γδ T cells, T cell receptor, T cell responses, Human infections, Tuberculosis, Phosphoantigen, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMBPP), HIV, Pneumonic plague

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that human γδ T cells function as non-classical T cells and contribute to both innate and adaptive immune responses in infections [1–4]. Vγ2 Vδ2 T (also termed Vγ9 Vδ2 T) cells exist only in primates, and in humans represent a major circulating γδ T cell subset that normally constitutes up to 65–90% of total peripheral blood γδ T cells. Since macaque Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells resemble their human counterparts, in-depth studies have been undertaken in nonhuman primates to understand biology and function of human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. This article reviews the recent progress for immune responses of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in infections.

Infection-driven adaptive immune responses of phosphoantigen-specific human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells

A number of laboratories including ours have demonstrated that Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can be activated in vitro by certain low m.w. foreign- and self-nonpeptidic phosphorylated metabolites of isoprenoid biosynthesis [e.g., (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMBPP), isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP)] [7–11] commonly referred to as phosphoantigens. Microbial phosphoantigen HMBPP is produced in the 2-C-methyl-Derythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis of a number of bacteria and protozoa [5]. Infections of humans or nonhuman primates with HMBPP-producing microbes can induce major expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [5]. Typically, Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis both produce HMBPP, and early infections of macaques with these mycobacteria can induce remarkable expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [1]. Surprisingly, BCG re-infection or BCG infection followed by M. tuberculosis challenge can induce rapid recall expansion or adaptive immune responses in macaques [1]. Re-occurrence of clonotypic TCR sequences of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells is also evident during rapid recall expansion, suggesting the memory-like responses [1]. Our new studies provide additional in vivo evidence indicating that rapid recall expansion or adaptive immune response of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can also be induced during re-infection of macaques with Listeria monocytogenes capable of producing HMBPP (Ryan et al., 2010 International γδ T cell conference). In fact, increases in human γδ T cells or Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells were reported in leprosy granulomatous disease and tuberculous meningitis, respectively (see review [6]). Examples for infection-driven expansion of human γδ T cells also include salmonellosis, brucellosis, legionellosis, tularemia, brucellosis, Legionellosis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, Leishmaniasis and others (see review [6]). The notion that human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can mount adaptive immune response in infections is also supported by other human studies [5, 7–12]. However, like CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells appear to be depressed in terms of frequency or effector function during chronically active tuberculosis or chronic phase of AIDS virus infections [13, 14]. It is still debatable as to whether such depressed Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells contribute to the development of active tuberculosis or result from immune dysfunction in chronic tuberculosis.

The extraordinary expansion and recall expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in infections indeed argue against the old simple paradigm that human γδ T cells completely function as innate cells. Notably, human γδ T cells have been long considered innate cells due to the lack of convincing evidence indicating major clonal expansion and adaptive feature for these γδ T cells. Nevertheless, the emerging evidence suggests that human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can have both innate and adaptive immune features in infections.

It is likely that the infections with HMBPP-producing pathogens are the driving forces for adaptive immune response of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. Our new in vivo studies suggest that both HMBPP and infection-driven cytokines are needed for clonal expansion and recall expansion (Ryan et al., unpublished data). This helps to explain at least in part why repeated in vivo treatments of macaques by a phospholigand and IL-2 can induce expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells each time, but not necessarily stimulate greater magnitudes of recall expansion each time after the treatment [15]. The finding derived from small phospholigand and IL-2 treatment cannot rule out the possibility that Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can contribute to adaptive immune response in infections in that Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells do not exactly resemble their αβ T cell counterpart mounting the typical recall or memory responses when exposed to the simple treatment comprised only of very small phospholigand molecule and IL-2. It is also possible that the initial treatment with phospholigand and IL-2 has already reached the maximum activation/expansion potential of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells (up to 80% of T cells are HMBPP/IL2-expanded γδ T cells [15, 16]), and a subsequent treatment will not be able to go beyond the saturated points due to the host self-control mechanism for shutting-down over-expanding T cell clones. A human in vitro study also implicates that HMBPP is different from infection in activation and function of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, as mycobacteria-stimulated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, but not HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, are able to suppress M. tuberculosis replication [17].

Molecular mechanism by which Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells interact with microbial phosphoantigen HMBPP during infections

Primate Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell subset remains the only γδ T cells capable of recognizing a microbial phosphoantigen, whereas no defined microbial antigens can be recognized by γδ T cells from mice and other species [1–4]. While the chemistry of phosphoantigens and their ability to activate Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells have been well described, molecular mechanisms by which HMBPP interacts with γδ T cells remain poorly characterized [18–21]. Most studies done to date have been focused on prenyl pyrophosphates, particularly IPP, but rarely the microbial phosphoantigen HMBPP [22]. Earlier experiments using Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell activation as readouts demonstrated that IPP does not need to undergo cell-entry or processing and that phosphoantigen activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells requires cell–cell contact [18, 23]. A putative molecule, but not MHC class I, class II, or CD1, appears to be required to present IPP for immune activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [18]. Despite decade-long studies, however, there has been no direct evidence indicating that human or macaque Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR (instead of human macaque hybrids) can directly bind to HMBPP or HMBPP complex [24, 25].

We presumed that the development of soluble, tetrameric Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR would provide a useful approach to explore the molecular mechanism by which Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells interact with phosphoantigen HMBPP. We therefore took advantage of our decades-long TCR expertise and MHC tetramer technology [26, 27] to develop high-affinity-binding soluble Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer [28]. We demonstrated that soluble Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer, once labeled with fluorescence, makes it possible to visualize APC presentation of phosphoantigen HMBPP to Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR [28]. We show that exogenous HMBPP is associated with APC membrane in an appreciable affinity, and that the membrane-associated HMBPP is readily recognized by the Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer (Fig. 1) [28]. In fact, the Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer stably binds HMBPP presented on membrane by various APC cell lines from humans and non-human primates but not those from mouse, rat or pig [28]. This finding suggests that Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR is one of the important elements dictating the specific recognition of microbial HMBPP by Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [28]. The Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer also binds the membrane-associated HMBPP on primary monocytes, B cells and some T cells, suggesting that various host immune cells can present HMBPP for activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during infections with HMBPP-producing pathogens [28]. Consistently, endogenous phosphoantigen produced in mycobacterium-infected DC is transported and presented on membrane, and stably bound to the Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer. This is particularly significant for host responses to infections with HMBPP-producing intracellular pathogens, as the infected APC, such as DC or macrophages, can rapidly present HMBPP to Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR for early activation and expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. Interestingly, the capability of APC to present HMBPP for recognition by Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR is diminished after protease treatment of APC. Thus, our studies elucidate that an affinity HMBPP–APC association confers binding to Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR, and that the putative APC membrane molecule presenting HMBPP appears to be a protein or protein-associated component existing in primate APC or T cells but not rodent APC [28]. Thus, the Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer-based studies enhance our understanding of molecular aspects for the interaction between Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells and APC presenting microbial phosphoantigen HMBPP in infections.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry histograms showed that FITC-labeled Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer bound to the membrane-associated HMBPP presented by macaque primary B cells, T cells and monocytes. Large proportions of these cell populations were stained positive by the Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer. No staining was seen for the two controls: (1) cells not pulsed with HMBPP and directly incubated with FITC-labeled Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR tetramer (no HMBPP/Vγ2 Vδ2); and (2) cells pulsed with HMBPP but incubated with the FITC-labeled Vγ1 Vδ2 TCR tetramer control (HMBPP/Vγ1 Vδ2)

Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR appears to play a fundamental role in recognition of HMBPP and subsequent clonal activation/expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during infections

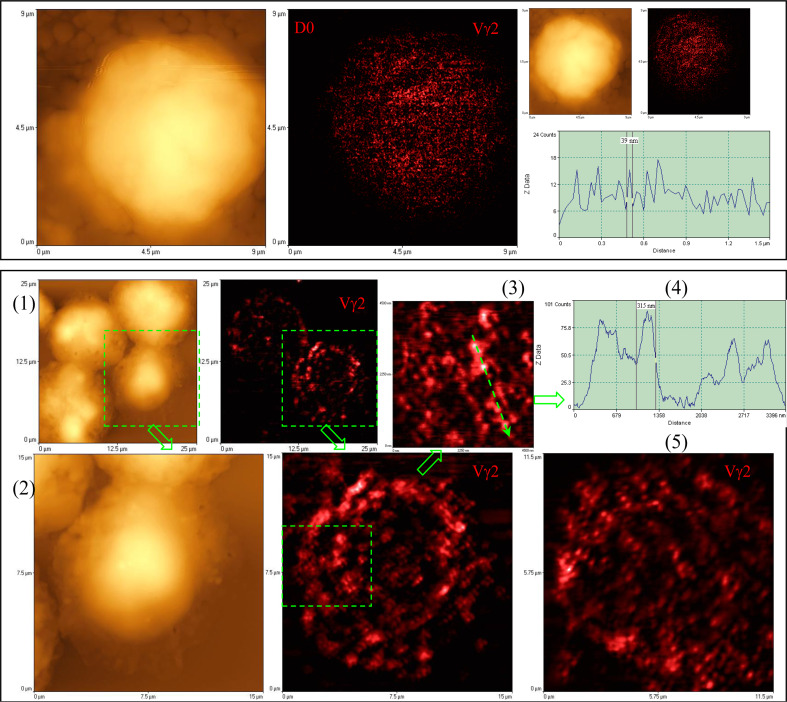

Since Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR dictates the specific interaction with microbial phosphoantigen HMBPP, it would be interesting to see the HMBPP-engaged TCR molecule events driving sequential activation and expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in early infections. We presume that molecular imaging of HMBPP-triggered TCR response would be a best approach to elucidate TCR molecule responses. We have innovatively combined near-field optical microscopy (NSOM) and fluorescent quantum dot (QD) nanotechnology (NSOM/QD), and developed a best-optical-resolution nanoscale molecular imaging (<50 nm) system for visualizing molecule events in immune cells. Such a best-optical-resolution molecular imaging system allows us to show that non-stimulating Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR molecules in resting γδ T cells are distributed individually from each other on the cell surface, with mean sizes of <50–70 nm (Fig. 2) [29]. However, HMBPP pulsation of APC for engaging Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR rapidly induces formation of ~120–300 nm TCR nanoclusters [29]. Such TCR molecule events coincide with the translocation of PKCθ to the membrane for signal transduction and activation (data not shown). Surprisingly, such Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR nanoclusters can be sustained on the membrane during an in vivo clonal expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells after HMBPP/IL-2 treatment and mycobacterial infection. The TCR nanoclusters can array to form nanodomains or microdomains on the membrane of clonally-expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 2) [29]. Interestingly, expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells bearing TCR nanoclusters or nanodomains were able to re-recognize phosphoantigen and to exert better effector function [29]. In contrast, non-specific stimulants cannot induce Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR nanoclustering or nanodomain formation. These nanoscale novel findings suggest that Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR plays a fundamental role in recognition of HMBPP and subsequent clonal activation and expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during infections with HMBPP-producing pathogens.

Fig. 2.

NSOM/QD-based nanoscale imaging shows that Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR arrayed to form high-density TCR nanoclusters, nanodomains and microdomains during the in vivo clonal expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells after HMBPP/IL-2 treatment. Upper panel shows representative NSOM topographic (left) and fluorescence (middle) images indicating the dominance of non-engaging fluorescence TCR dots on the membrane of unstimulated Vγ2 T cells on day 0. The fluorescent intensity profile graph (right) is extracted from a random cross section in the fluorescence image (middle) showing that predominant fluorescence TCR dots here displayed FWHM of ~50 nm. Lower panel shows representative NSOM images of TCR nanoclusters, nanodomains and microdomains on the membrane of clonally expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells on day 4. (2) is enlarged from the boxed area in the low-magnification NSOM image (1). The fluorescence intensity profile (4) is extracted from the cross section part (dashed arrow) in (3) that is enlarged from the boxed area in (2). (5) is the NSOM fluorescence image of another activated/expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell collected on day 4

A critical role of cytokines in adaptive immune responses of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in infections

Some cytokines produced in infections may contribute to the development of adaptive immune responses of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during infections with HMBPP-producing pathogens. This scenario is supported by the studies from us [2] and others [30]. We found that M. tuberculosis and BCG infections of macaques induced major expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells and coincident expression of variant IL-4 (VIL-4) mRNA encoding a protein comprised of N-terminal 97 amino acids (a.a.) identical to IL-4, and unique C-terminal 96 a.a. including a signaling-related proline-rich motif. We then expressed and purified VIL-4 to test the possibility that this variant cytokine can contribute to major expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. The purified VIL-4 induces apparent expansion of phosphoantigen HMBPP-specific Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in dose- and time-dependent manners [2]. The unique C-terminal 96 a.a. bearing the proline-rich motif (PPPCPP) of VIL-4 appears to confer the ability to expand Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, since simultaneously produced IL-4 has only a subtle effect on these γδ T cells. Moreover, VIL-4 seems to utilize IL-4 receptor α for signaling and activation, as the VIL-4-induced expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can be blocked by anti-IL-4R α mAb but not anti-IL-4 mAb [2]. Surprisingly, VIL-4-expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells after HMBPP stimulation appear to be heterologous effector cells capable of producing IL-4, IFN-γ and TNF-α [2]. Thus, mycobacterial infections of macaques induced variant mRNA encoding VIL-4 that functions as growth factor promoting expansion of HMBPP-specific Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells [2]. We presume that other cytokines may also exert similar effects facilitating major expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during mycobacterial infections. In fact, it has been reported that IL-21 can also stimulate marked expansion of HMBPP-specific Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [30]. Our new studies also demonstrate that IL-17, IL-22 and IL-23 can contribute to significant expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells after mycobacterial infection (Ryan et al., 2010 International γδ T cell conference). Human in vitro studies also showed that IL-15 could help to develop antimicrobial function of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in M. tuberculosis infection [31]. Since HMBPP alone or cytokine alone is not able to induce major expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, IL-2 or other cytokines may function as “second or third signal” for sustaining HMBPP/TCR-mediated activation and clonal expansion in infections.

Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells may potentially enhance Ag-specific Ab response and αβ CD4+ or CD8+ T cell responses in infections

It has been long postulated that γδ T cells may bridge innate and adaptive immune responses in infection presumably due to the enriched distribution of γδ T cells in mucosa. Such a hypothesis has not been well tested in mice since mouse γδ T cells do not recognize phosphoantigen HMBPP or other microbial antigens. To address this, we treat macaques with HMBPP compound plus IL-2 regimen to investigate if activation/expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can impact immune responses in infections. We first defined the utility and immune kinetics of the single-dose HMBPP plus 5-day IL-2 treatment regimen in macaques, and found that this regimen could expand macaque Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells from baseline 1 up to 80% in the T cell pool without detectable side effects [16, 29]. The HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells produced IFNγ and other cytokines, readily trafficked to lung, oral and gut mucosa, and sustained their pulmonary accumulation for months [16]. We then investigated whether this well-defined HMBPP/IL-2 therapeutic regimen could overcome HIV-mediated immune suppression to massively expand polyfunctional Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells, and whether such activation/expansion could impact AIDS pathogenesis in simian HIV (SHIV)-infected macaques. HMBPP/IL-2 coadministration during chronic phase of SHIV infection induced massive activation/expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. HMBPP/IL-2 cotreatment during chronic infection did not exacerbate disease, and more importantly it could confer immunological benefits. Surprisingly, although viral antigenic loads were decreased upon HMBPP/IL-2 cotreatment during chronic SHIV infection, HMBPP activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells boosted HIV Env-specific Ab titers. Such increases in Abs were sustained for >170 days and were immediately preceded by increased production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10 during peak expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells displaying memory phenotypes, as well as the short-term increased effector function of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells and CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells producing antimicrobial cytokines. The significance for these findings are twofold: (1) HMBPP/Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell-based intervention is potentially useful for combating neoplasms and HMBPP-producing opportunistic pathogens in chronically HIV-infected individuals; and (2) HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells may function as adjuvant and facilitate B cells producing Abs, and enhance CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells producing antimicrobial cytokines during infections. In fact, these observations in macaques are consistent with the findings in the in vitro human studies. It has been shown that activation of human γδ T cells can stimulate DC maturation [32, 33]. The HMBPP-dependent cross-talk between monocytes and human γδ T cells can drive fast inflammatory cytokine responses and monocyte differentiation to DC, and facilitate development CD4 T helper cells in the presence of additional microbial stimulants [34]. Activated human Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells appear to function as APC in vitro, presenting peptide antigens to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [35, 36]. Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells have also been shown to improve B cells’ ability to produce antibodies in vitro [32]. Further studies are needed to prove the tentative concept that Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells may potentially enhance Ag-specific Ab response and αβ CD4+ or CD8+ T cell responses in infections.

Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells may function as immune regulators influencing other immune cells and their responses in infections

Activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells produce Th1 cytokines and many other cytokines, and therefore may influence other effector cells in host responses to infections. To assess this possibility, we sought to determine whether Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells could have direct impact on other T cell populations in vivo during infections or vaccination. Our studies were focused on two aspects: (1) interplay between CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Treg) and HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells during mycobacterial infection; and (2) Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell-driven immune regulation of potentially inflammatory IL-22+ T cells in tuberculosis.

Foxp3+ Treg cells control immune responses to self- and foreign-antigens and play a major role in maintaining the balance between immunity and tolerance [37–39]. While Treg are beneficial for controlling autoimmunity, allograft rejection, or hypersensitivity, their over-responses in infections may lead to suppression of host anti-microbial immunity [37]. Development of a useful model system may help to identify potential mutual regulatory effects of Treg and other immune cells or elements. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that human recombinant IL-2 administration can lead to an increase in the frequency of circulating CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in cancer patients [40–43]. We and others have also shown that IL-2 plus phospholigand treatment can induce remarkable expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in nonhuman primates [15, 16, 44]. We therefore took advantage of the IL-2-based in vivo model systems to assess potential interplay or mutual regulations between Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells and Treg during early mycobacterial infection in nonhuman primates. A short-term IL-2 treatment regimen induced marked expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells, and subsequent suppression of mycobacterium-driven increases Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in acutely BCG-infected macaques. Surprisingly, activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells by adding phosphoantigen Picostim (similar to HMBPP) to the IL-2 treatment regimen apparently down-regulates IL-2-induced expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells [44]. The down-regulation of IL-2-induced expansion of Treg coincides with the sustained increases in numbers of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells through 42 days after the Picostim/IL-2 treatment and superimposed BCG infection. Consistently, in vitro activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in PBMC by phosphoantigen+IL-2 can down-regulate IL-2-induced expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells, but HMBPP-mediated antagonizing effect appears to require APC (monocytes) or other lymphocytes [44]. Since activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells alone had no inhibiting effect on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in the culture without APC and other cells in PBMC, we sought to determine whether some cytokines produced by phosphoantigen-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells contributed to the down-regulation of the IL-2-induced proliferation of Treg. We set up cytokine-neutralizing experiments in the proliferation assays using anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-4, or anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibodies because HMBPP phosphoantigen stimulation could up-regulate many genes including those encoding those cytokines (Wang et al., data not shown). Surprisingly, while anti-TGF-β or anti-IL-4 neutralizing antibodies did not affect the HMBPP-mediated down-regulation of Treg, anti-IFN-γ neutralizing antibody significantly reduced the ability of HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells to antagonize Treg expansion [44]. This suggests that Th1 network contributed to Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells’ antagonizing effects. Furthermore, activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells by Picostim + IL-2 treatment appears to reverse Treg-driven suppression of immune responses of phosphoantigen-specific IFNγ+ or perforin+Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells and PPD-specific IFNγ+αβ T cells [44]. Thus, phosphoantigen-activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can antagonize IL-2-induced expansion of Treg and subsequent suppression of and anti-microbial T cell responses in mycobacterial infections. The findings from phosphoantigen/IL-2 treatment of macaques in the context of mycobacterial infection provide the first evidence suggesting that certain T cell subsets in the immune system can antagonize Foxp3+Treg and their suppression of Ag-specific T cell responses in infections.

Given the possibility that some over-reacting T effector cells may contribute to inflammation or tissue damages in infections, we sought to determine if HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can regulate those potentially inflammatory cells. In this end, we focused on IL-22+ T cells and their interplay with Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in infection as IL-22 has been shown to play a role in inflammation or autoimmunity [45–47]. We first demonstrated in a nonhuman primate model that M. tuberculosis infection results in apparent increases in numbers of T cells capable of producing IL-22 de novo without in vitro Ag stimulation, and drives distribution of these cells more dramatically in lungs than in blood and lymphoid tissues [18, 19]. Consistently, IL-22+ T cells are visualized in situ in lung tuberculosis (TB) granulomas by confocal microscopy and immunohistochemistry, indicating that mature IL-22+ T cells are present in TB granuloma [18, 19]. Surprisingly, HMBPP activation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells down-regulates the capability of T cells to produce IL-22 de novo in lymphocytes from blood, lung/BAL fluid, spleen and lymph node [18]. Up-regulation of IFNγ-producing Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells after HMBPP stimulation coincides with the down-regulated capacity of these T cells to produce IL-22 de novo. Importantly, anti-IFNγ neutralizing Ab treatment reversed the HMBPP-mediated down-regulation effect on IL-22+ T cells, suggesting that Vγ2 Vδ2 T cell-driven IFNγ-networking function was the mechanism underlying the HMBPP-mediated down-regulation of the capability of T cells to produce IL-22 [18]. These novel findings raise the possibility to ultimately investigate the function of IL-22+ T cells and to target Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells for balancing potentially hyper-activating IL-22+ T cells in severe TB.

Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells can readily traffic to lungs and contribute to host resistance to pathogen-induced lung damages during acute pulmonary infection

Our studies have demonstrated that one of the remarkable immune features for HMBPP-specific Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells is their capability to traffic to lungs and other mucosal surface once they are activated and expanded [16, 48]. However, the possibility that Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells can confer protection against pulmonary infectious diseases has not been tested. Since we reproducibly showed that the HMBPP plus IL-2 treatment can induce prolonged accumulation of Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells in lungs [16, 29, 44, 49], we investigated whether the expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can mediate protection against acutely fatal pneumonic plague in the macaque model of inhalational Yersinia pestis infection. A delayed HMBPP/IL-2 administration after inhalational Yersinia pestis infection overcame acute infection and induced marked expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells [49]. Expanded Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells failed to control extracellular plague bacterial replication/infection, which led to extrathoracic dissemination, septicemia and fatal shock. This appeared to be understandable since an extracellular bacterial infection would usually be controlled by neutralizing antibodies but not T effector cells. Surprisingly, despite the absence of infection control, expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells after HMBPP/IL-2 treatment led to the attenuation of inhalation plague lesions in lungs [49]. Consistently, HMBPP-activated Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells accumulated and localized in pulmonary interstitials surrounding small blood vessels and airway mucosa in the lung tissues with no or mild plague lesions [49]. These infiltrating Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells produced FGF-7, a homeostatic mediator against tissue damages [50]. In contrast, control macaques treated with glucose plus IL-2 or glucose alone exhibited severe hemorrhages and necrosis in most lung lobes, with no or very few Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells detectable in lung tissues. The findings are consistent with the paradigm that circulating Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can traffic to lungs for homeostatic protection against tissue damages in infection. This finding indeed provides the first in vivo evidence in humans and primates indicating that Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells can contribute to anti-microbial immunity.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, much progress has been made over the past years. While infections with phosphoantigen-producing microbes can drive adaptive immune responses of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells in humans and nonhuman primates, Vγ2 Vδ2 TCR appears to be responsible for recognition of phosphoantigen HMBPP presented by APC and subsequent clonal activation/expansion of Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells during infections. IL-2 and other cytokines produced in infections play a critical role in mounting adaptive immune responses of HMBPP-specific Vγ2 Vδ2 T cells. Preliminary data suggest that Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells may potentially enhance Ag-specific Ab response and αβ CD4+ or CD8+ T cell responses in infections. In addition, Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells may function as immune regulators antagonizing CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells and influencing IL-22+ T effector cells in infections. Importantly, Vγ2 Vδ2 T effector cells can readily traffic to lungs and contribute to host resistance to pathogen-induced lung damage during an acute pulmonary infection.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Chen Lab staff for technical supports and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 Grants; HL64560 and RR13601 (both to Z.W.C.).

References

- 1.Shen Y, Zhou D, Qiu L, Lai X, Simon M, Shen L, Kou Z, Wang Q, Jiang L, Estep J, Hunt R, Clagett M, Sehgal PK, Li Y, Zeng X, Morita CT, Brenner MB, Letvin NL, Chen ZW. Adaptive immune response of Vgamma2Vdelta2 + T cells during mycobacterial infections. Science. 2002;295:2255–2258. doi: 10.1126/science.1068819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan Z, Wang R, Lee Y, Chen CY, Yu X, Wu Z, Huang D, Shen L, Chen ZW. Tuberculosis-induced variant IL-4 mRNA encodes a cytokine functioning as growth factor for (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate-specific Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:811–819. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien RL, Roark CL, Jin N, Aydintug MK, French JD, Chain JL, Wands JM, Johnston M, Born WK. Gammadelta T-cell receptors: functional correlations. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thedrez A, Sabourin C, Gertner J, Devilder MC, Allain-Maillet S, Fournie JJ, Scotet E, Bonneville M. Self/non-self discrimination by human gammadelta T cells: simple solutions for a complex issue? Immunol Rev. 2007;215:123–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen ZW, Letvin NL. Adaptive immune response of Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells: a new paradigm. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen ZW, Letvin NL. Vgamma2Vdelta2 + T cells and anti-microbial immune responses. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:491–498. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita CT, Mariuzza RA, Brenner MB. Antigen recognition by human gamma delta T cells: pattern recognition by the adaptive immune system. Semin Immunopathol. 2000;22:191–217. doi: 10.1007/s002810000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieli F, Poccia F, Lipp M, Sireci G, Caccamo N, Di Sano C, Salerno A. Differentiation of effector/memory Vdelta2 T cells and migratory routes in lymph nodes or inflammatory sites. J Exp Med. 2003;198:391–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitard V, Roumanes D, Lafarge X, Couzi L, Garrigue I, Lafon ME, Merville P, Moreau JF, Dechanet-Merville J. Long-term expansion of effector/memory Vdelta2-gammadelta T cells is a specific blood signature of CMV infection. Blood. 2008;112:1317–1324. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poccia F, Agrati C, Castilletti C, Bordi L, Gioia C, Horejsh D, Ippolito G, Chan PK, Hui DS, Sung JJ, Capobianchi MR, Malkovsky M. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus immune responses: the role played by V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cells. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1244–1249. doi: 10.1086/502975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abate G, Eslick J, Newman FK, Frey SE, Belshe RB, Monath TP, Hoft DF. Flow-cytometric detection of vaccinia-induced memory effector CD4(+), CD8(+), and gamma delta TCR(+) T cells capable of antigen-specific expansion and effector functions. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1362–1371. doi: 10.1086/444423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoft DF, Brown RM, Roodman ST. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination enhances human gamma delta T cell responsiveness to mycobacteria suggestive of a memory-like phenotype. J Immunol. 1998;161:1045–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZW. Immunology of AIDS virus and mycobacterial co-infection. Curr HIV Res. 2004;2:351–355. doi: 10.2174/1570162043351147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen L, Shen Y, Huang D, Qiu L, Sehgal P, Du GZ, Miller MD, Letvin NL, Chen ZW. Development of Vgamma2Vdelta2 + T cell responses during active mycobacterial coinfection of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques requires control of viral infection and immune competence of CD4 + T cells. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1438–1447. doi: 10.1086/423939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sicard H, Ingoure S, Luciani B, Serraz C, Fournie JJ, Bonneville M, Tiollier J, Romagne F. In vivo immunomanipulation of V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cells with a synthetic phosphoantigen in a preclinical nonhuman primate model. J Immunol. 2005;175:5471–5480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali Z, Shao L, Halliday L, Reichenberg A, Hintz M, Jomaa H, Chen ZW. Prolonged (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate-driven antimicrobial and cytotoxic responses of pulmonary and systemic Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells in macaques. J Immunol. 2007;179:8287–8296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer CT, Abate G, Blazevic A, Hoft DF. Only a subset of phosphoantigen-responsive gamma9delta2 T cells mediate protective tuberculosis immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:4471–4484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao S, Huang D, Chen CY, Halliday L, Zeng G, Wang RC, Chen ZW. Differentiation, distribution and gammadelta T cell-driven regulation of IL-22-producing T cells in tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000789. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vani J, Shaila MS, Rao MK, Krishnaswamy UM, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. B lymphocytes from patients with tuberculosis exhibit hampered antigen-specific responses with concomitant overexpression of interleukin-8. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:481–482. doi: 10.1086/599843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belmant C, Espinosa E, Poupot R, Peyrat MA, Guiraud M, Poquet Y, Bonneville M, Fournie JJ. 3-Formyl-1-butyl pyrophosphate A novel mycobacterial metabolite-activating human gammadelta T cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32079–32084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eberl M, Altincicek B, Kollas AK, Sanderbrand S, Bahr U, Reichenberg A, Beck E, Foster D, Wiesner J, Hintz M, Jomaa H. Accumulation of a potent gammadelta T-cell stimulator after deletion of the lytB gene in Escherichia coli . Immunology. 2002;106:200–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarikonda G, Wang H, Puan KJ, Liu XH, Lee HK, Song Y, Distefano MD, Oldfield E, Prestwich GD, Morita CT. Photoaffinity antigens for human gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7738–7750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verreck FA, de Boer T, Langenberg DM, Hoeve MA, Kramer M, Vaisberg E, Kastelein R, Kolk A, de Waal-Malefyt R, Ottenhoff TH. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Tanaka Y, Bloom BR, Brenner MB, Band H. V gamma 2 V delta 2 TCR-dependent recognition of non-peptide antigens and Daudi cells analyzed by TCR gene transfer. J Immunol. 1995;154:998–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Lee HK, Bukowski JF, Li H, Mariuzza RA, Chen ZW, Nam KH, Morita CT. Conservation of nonpeptide antigen recognition by rhesus monkey V gamma 2 V delta 2 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3696–3706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen ZW, Li Y, Zeng X, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Shen Y, Lai X, Shen L, Letvin NL. The TCR repertoire of an immunodominant CD8 + T lymphocyte population. J Immunol. 2001;166:4525–4533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei H, Wang R, Yuan Z, Chen CY, Huang D, Halliday L, Zhong W, Zeng G, Shen Y, Shen L, Wang Y, Chen ZW. DR*W201/P65 tetramer visualization of epitope-specific CD4 T-cell during M. tuberculosis infection and its resting memory pool after BCG vaccination. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei H, Huang D, Lai X, Chen M, Zhong W, Wang R, Chen ZW. Definition of APC presentation of phosphoantigen (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate to Vgamma2/Vdelta 2 TCR. J Immunol. 2008;181:4798–4806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Shao L, Ali Z, Cai J, Chen ZW. NSOM/QD-based nanoscale immunofluorescence imaging of antigen-specific T-cell receptor responses during an in vivo clonal V{gamma}2 V{delta}2 T-cell expansion. Blood. 2008;111:4220–4232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermijlen D, Ellis P, Langford C, Klein A, Engel R, Willimann K, Jomaa H, Hayday AC, Eberl M. Distinct cytokine-driven responses of activated blood gammadelta T cells: insights into unconventional T cell pleiotropy. J Immunol. 2007;178:4304–4314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meraviglia S, Caccamo N, Salerno A, Sireci G, Dieli F. Partial and ineffective activation of V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cells by Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:1770–1776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caccamo N, Battistini L, Bonneville M, Poccia F, Fournie JJ, Meraviglia S, Borsellino G, Kroczek RA, La Mendola C, Scotet E, Dieli F, Salerno A. CXCR5 identifies a subset of Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells which secrete IL-4 and IL-10 and help B cells for antibody production. J Immunol. 2006;177:5290–5295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ismaili J, Olislagers V, Poupot R, Fournie JJ, Goldman M. Human gamma delta T cells induce dendritic cell maturation. Clin Immunol. 2002;103:296–302. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberl M, Roberts GW, Meuter S, Williams JD, Topley N, Moser B. A rapid crosstalk of human gammadelta T cells and monocytes drives the acute inflammation in bacterial infections. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000308. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandes M, Willimann K, Bioley G, Levy N, Eberl M, Luo M, Tampe R, Levy F, Romero P, Moser B. Cross-presenting human gammadelta T cells induce robust CD8 + alphabeta T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810059106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meuter S, Eberl M, Moser B. Prolonged antigen survival and cytosolic export in cross-presenting human gammadelta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8730–8735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002769107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3 + T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR. Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity. 2009;30:656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belkaid Y, Tarbell KV. Arming Treg cells at the inflammatory site. Immunity. 2009;30:322–323. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Chua KS, Guimond M, Kapoor V, Brown MV, Fleisher TA, Long LM, Bernstein D, Hill BJ, Douek DC, Berzofsky JA, Carter CS, Read EJ, Helman LJ, Mackall CL. Lymphopenia and interleukin-2 therapy alter homeostasis of CD4 + CD25 + regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:1238–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. IL-2 administration increases CD4 + CD25(hi) Foxp3 + regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Blood. 2006;107:2409–2414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zorn E, Nelson EA, Mohseni M, Porcheray F, Kim H, Litsa D, Bellucci R, Raderschall E, Canning C, Soiffer RJ, Frank DA, Ritz J. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4 + CD25 + regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei S, Kryczek I, Edwards RP, Zou L, Szeliga W, Banerjee M, Cost M, Cheng P, Chang A, Redman B, Herberman RB, Zou W. Interleukin-2 administration alters the CD4 + FOXP3 + T-cell pool and tumor trafficking in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7487–7494. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong G, Shao L, Wang Y, Chen CY, Huang D, Yao S, Zhan X, Sicard H, Wang R, Chen ZW. Phosphoantigen-activated V gamma 2 V delta 2 T cells antagonize IL-2-induced CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + T regulatory cells in mycobacterial infection. Blood. 2009;113:837–845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, Kasman I, Eastham-Anderson J, Wu J, Ouyang W. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Agius E, Booth N, Dunne PJ, Lacy KE, Reed JR, Sobande TO, Kissane S, Salmon M, Rustin MH, Akbar AN. The kinetics of CD4Foxp3 T cell accumulation during a human cutaneous antigen-specific memory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3639–3650. doi: 10.1172/JCI35834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson MS, Feng CG, Barber DL, Yarovinsky F, Cheever AW, Sher A, Grigg M, Collins M, Fouser L, Wynn TA. Redundant and pathogenic roles for IL-22 in mycobacterial, protozoan, and helminth infections. J Immunol. 2010;184:4378–4390. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang D, Shen Y, Qiu L, Chen CY, Shen L, Estep J, Hunt R, Vasconcelos D, Du G, Aye P, Lackner AA, Larsen MH, Jacobs WR, Jr, Haynes BF, Letvin NL, Chen ZW. Immune distribution and localization of phosphoantigen-specific Vgamma2 Vdelta2 T cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:426–436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang D, Chen CY, Ali Z, Shao L, Shen L, Lockman HA, Barnewall RE, Sabourin C, Eestep J, Reichenberg A, Hintz M, Jomaa H, Wang R, Chen ZW. Antigen-specific Vgamma2 Vdelta2 T effector cells confer homeostatic protection against pneumonic plaque lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7553–7558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811250106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jameson J, Ugarte K, Chen N, Yachi P, Fuchs E, Boismenu R, Havran WL. A role for skin gammadelta T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]