Abstract

Speech elicits a phase-locked response in the auditory cortex that is dominated by theta (3–7 Hz) frequencies when observed via magnetoencephalography (MEG). This phase-locked response is potentially explained as new phase-locked activity superimposed on the ongoing theta oscillation or, alternatively, as phase-resetting of the ongoing oscillation. The conventional method used to distinguish between the two hypotheses is the comparison of post- to prestimulus amplitude for the phase-locked frequency across a set of trials. In theory, increased amplitude indicates the presence of additive activity, while unchanged amplitude points to phase-resetting. However, this interpretation may not be valid if the amplitude of ongoing background activity also changes following the stimulus. In this study, we employ a new approach that circumvents this problem. Specifically, we utilize a fine-grained time–frequency analysis of MEG channel data to examine the co-modulation of amplitude change and phase coherence in the post-stimulus theta-band response. If the phase-locked response is attributable solely to phase-resetting of the ongoing theta oscillation, then amplitude and phase coherence should be uncorrelated. In contrast, additive activity should produce a positive correlation. We find significant positive correlation not only during the onset response but also throughout the response period. In fact, transient increases in phase coherence are accompanied by transient increases in amplitude in accordance with a “signal plus background” model of the evoked response. The results support the hypothesis that the theta-band phase-locked response to attended speech observed using MEG is dominated by additive phase-locked activity.

Keywords: Auditory, Speech, MEG, Evoked, Phase, Amplitude

Introduction

Natural speech stimuli give rise to neuronal activity that is phase-locked to the slow modulations of the speech envelope and observable in the neuromagnetic (MEG) and neuroelectric (EEG) response (Abrams et al., 2008; Ahissar et al., 2001; Aiken and Picton, 2008; Deng and Srinivasan, 2010). Phase-locked activity, also referred to as the evoked response (David et al., 2006), appears to be particularly robust within the theta band (3–7 Hz) for these stimuli (Howard and Poeppel, 2010; Luo and Poeppel, 2007; Luo et al., 2010). The neuronal activity underlying the evoked response is not completely understood, but is potentially explained by two competing theories: additive activity and phase-resetting of ongoing oscillations (for review see Sauseng et al., 2007). The additive theory, strictly interpreted, proposes that new phase-locked activity, generated in response to the stimulus, is superimposed on unchanged background activity. The phase-resetting theory, strictly interpreted, proposes that the phase of an ongoing oscillation present in the background activity is reset, effectively time-locking it to the stimulus. Both theories predict phase concentration over repeated trials such that the evoked response emerges upon trial averaging. However, the two theories, under the strict interpretations stated above, lead to different predictions with respect to amplitude (or power) change for the prominent frequencies in the evoked response. Specifically, the additive theory implies that the amplitude of these frequencies will increase over prestimulus levels in the post-stimulus response, while the phase-resetting theory implies that amplitude will remain the same.1 A number of studies have argued in favor of the additive (Hamada, 2005; Jervis et al., 1983; Mäkinen et al., 2005; Shah et al., 2004) or the phase-resetting (Hanslmayr et al., 2007; Jansen et al., 2003; Makeig et al., 2002; Sayers et al., 1974) theory or a combination of the two (Fell et al., 2004; Fuentemilla et al., 2006) on the basis of amplitude change analyses. However, critics point out that this approach depends crucially on the assumption that the amplitude of the ongoing oscillation is unaffected by the stimulus (Sauseng et al., 2007). Otherwise, a decrease in the amplitude of the ongoing oscillation could mask an increase in post-stimulus amplitude caused by additive phase-locked activity, while an increase would suggest an additive phase-locked contribution when only phase-resetting is actually involved. Thus, additive phase-locked activity cannot be distinguished from pure phase-resetting solely on the basis of the amplitude change observed in the post-stimulus response.

In this study, we pursue an analytical approach that allows us to distinguish between additive activity and pure phase-resetting even in the presence of changes in background oscillation amplitude. Specifically, we utilize a fine-grained time–frequency analysis of the response to examine the co-modulation of amplitude change and phase coherence in the post-stimulus theta-band response. The additive activity theory implies that any transient increases in phase coherence observed in the post-stimulus response data will be accompanied by transient increases in amplitude in a manner that can be predicted by a “signal plus background” model. In contrast, the pure phase-resetting theory implies that transient increases in phase coherence will not be reliably associated with transient increases in amplitude. Changes in background oscillation amplitude can be expected to shift the observed amplitude–phase coherence relationship curve relative to that predicted by either theory but have no effect on the relationship characteristics that distinguish the two theories. Thus, amplitude change and phase coherence should be positively correlated in the case of additive activity but uncorrelated in the case of pure phase resetting, regardless of changes in the amplitude of the background oscillation. Using this approach, the change in background amplitude during the post-stimulus response can be estimated from amplitude change values associated with near-zero phase coherence during the period of interest.

This study serves as an investigation of a hypothesis derived from recent research on the discrimination of attended speech stimuli based on phase and power patterns present in the neuromagnetic response arising in the auditory cortex (Howard and Poeppel, 2010; Luo and Poeppel, 2007). Luo and Poeppel (2007) found that spoken, attended sentences can be discriminated on the basis of theta-band phase, but not power, patterns present in single-trial response data. Howard and Poeppel (2010) confirmed these findings and utilized a signal plus background model to demonstrate that the experimental results for both phase and power are consistent with the presence of additive phase-locked theta activity. The modeling results led to the hypothesis that additive phase-locked theta activity is present in the response to attended speech such that a significant positive correlation will be observed between transient changes in phase coherence and amplitude across a large number of trials. Here, we test this hypothesis by examining the theta-band response in a large trial set for evidence of phase coherence and amplitude co-modulation as predicted by the signal plus background model. A finding of significant co-modulation would imply that the phase-locked theta response to the attended speech stimulus cannot be explained as a pure resetting of the ongoing oscillation but must reflect additive activity, even if no significant pre-to-post stimulus amplitude enhancement is observed.

Material and methods

Subjects

Thirteen subjects (6 male, mean age 23 yr, range 19–32 yr) took part in the experiment after providing informed consent. All were right-handed (Oldfield, 1971), English-speakers, reported normal hearing, and had no history of neurological disorders. The experiment was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland.

Stimuli

Three sentences with lengths exceeding 4000 ms were selected from the DARPA TIMIT Acoustic-Phonetic Continuous Speech Corpus (sampling frequency 16 kHz, male speaker, 1) “Maybe it’s taking longer to get things squared away than the bankers expected.”, 2) “His tough honesty condemned him to a difficult and solitary existence.”, 3) “The most recent geological survey found seismic activity.”) Stimuli consisted of an unmodified version of each sentence and a modified version constructed by raising the pitch of the final word. The first 3600 ms (at a minimum) were the same for both versions of the sentence in all cases. For all sentences, the auditory signal onset occurred approximately 110 ms after the stimulus initiation (trigger) point.

Procedure

All stimuli were delivered at a comfortable loudness level (~70 dB) through plastic tubing connected to ear pieces inserted in the ear canals of the subjects (EAR Tone 3A System). Presentation of the experimental stimuli was preceded by pretesting to check subject hearing and head position. The pretest included the binaural presentation of tone stimuli (1000 Hz, 50 ms, mean 137 per subject). The data recorded for these stimuli were used to localize channels reflecting response activity originating in the auditory cortex (see Data processing).

Experimental stimuli were presented diotically using Presentation software version 11.3 (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.). Stimuli were grouped in six blocks, with each of the six stimuli (two versions for each of the three sentences) presented 10 times per block in pseudo-random order. Thus, each sentence was presented 20 times per block, yielding a total of 120 trials for each sentence. The interstimulus (silent) interval was determined mainly by stimulus length and could take on values of approximately 1460, 1475, or 2005 ms. Subjects were instructed to decide if each stimulus was the modified or unmodified version of a sentence and to respond accordingly via a hand-held button press immediately after sentence completion. The sole purpose of this task was to keep subjects alert and attending to the stimuli in order to enhance the phase-locked evoked “signal” to background “noise” ratio (SNR) (Davis, 1964; Gross et al., 1965; Keating and Ruhm, 1971; Picton and Hillyard, 1974; Picton et al., 1971; Satterfield, 1965; Spong et al., 1965), as phase dissimilarity effects cannot be detected in single-trial data at low SNR levels. Subjects were allowed to rest between blocks and were instructed to change hands and then begin a new block (controlled by button press) when they were alert and ready.

Neuromagnetic recording

The neuromagnetic data were acquired in a magnetically shielded room (Yokogawa, Japan) using a 160-channel, whole-head axial gradiometer system (5 cm baseline, SQUID-based sensors, KIT, Kanazawa, Japan). MEG channels included 157 head channels plus 3 reference channels that recorded the environmental magnetic field data for noise reduction purposes. Data were continuously recorded using a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, on-line filtered between 1 and 100 Hz with a notch at 60 Hz.

Data processing

The recorded responses to the pretest tone stimuli were averaged, noise-reduced off-line using the CALM algorithm (Adachi et al., 2001), and base-line corrected. The results were then averaged across all subjects and low-pass filtered (22 Hz filter, 91 point Hamming window) in order to extract the grand average slow-wave response. Because the M100 (also referred to as N1m and N100m) component of the slow-wave response, generated approximately 100 ms after stimulus onset, reflects activity arising in the auditory cortex (Lütkenhöner and Steinsträter, 1998), the topography at the M100 peak (97 ms) was used to determine a set of 80 auditory cortex activity channels, with 20 selected from each quadrant (Fig. 1).

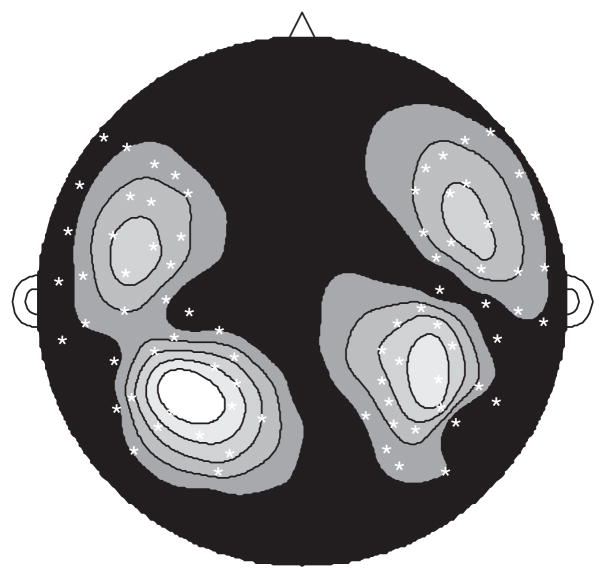

Fig. 1.

Topography of grand-average M100 peak response to 1000 Hz tones based on grayscale map of magnetic field absolute values from highest (white) to lowest (black). Auditory cortex activity channel set (80 channels) is indicated by white “×” marks.

The recorded responses to the experimental stimuli were noise-reduced using the time-shift principle component analysis algorithm (TSPCA) (de Cheveigné and Simon, 2007). Only the first 3600 ms section of each post-trigger response was retained so that the responses to the two versions of a sentence could be combined in subsequent analyses. A pre-trigger response of 900 ms was also retained for each trial, resulting in a total epoch length of 4500 ms.

Power and phase dissimilarity analysis

Post-trigger responses for each sentence were analyzed for power and phase pattern dissimilarity effects using the same methods described in Luo and Poeppel (2007) and Howard and Poeppel (2010). In order to maximize consistency with the analyses performed in these earlier studies, which were based on 21 responses presented in a single block, the first 18 responses (multiple of three required for analysis as explained below) of the first block (20 responses per block) were used in the analysis. Specifically, spectrograms of the 3600 ms response, based on a 500 ms time window and 100 ms steps, were computed for all 157 channels. For each channel, three within-sentence groups were formed, each comprising the spectrogram response data for a particular sentence (18 trials). Three across-sentence groups were also constructed, each comprising the spectrogram response data for six randomly selected trials for each of the three sentences (18 trials in total). Cross-trial phase and power coherence were computed as:

where θknij and Aknij are, respectively, the phase and amplitude for frequency bin i and time bin j in trial n and group k with N=18 (total number of trials) for this analysis. The cross-trial coherence values were used to compute a dissimilarity function for each frequency bin i defined as:

For this analysis, J =32 (total number of time bins) and K =3 (total number of groups). A positive index value means that a phase or power pattern is more dissimilar between the within-sentence groups than between the across-sentence groups. Dissimilarity index values were computed for each of the 157 MEG channels and averaged across all subjects to produce grand average index values for each channel. For each subject, mean dissimilarity index values were computed across the 80 auditory cortex activity channels (see Fig. 1). Grand averages across subjects were then computed for the 80-channel mean dissimilarity index values.

Amplitude and phase modulation analysis

The analysis of co-modulation of phase coherence and amplitude was performed utilizing those subjects whose response data exhibited cross-trial theta-band phase coherence, as reflected in positive theta-band phase dissimilarity index values that significantly exceed the random effects level. Because all negative phase dissimilarity index results are attributable solely to random effects, they were used to establish an upper bound on the random effects range. A conservative criterion for statistical significance was determined by defining the upper bound of random effects as the absolute value of the lower confidence limit on the bootstrap grand average [10,000 iterations, bias-corrected and accelerated method (Efron, 1987)] of the minimum (negative) 80-channel phase dissimilarity index value across all frequencies for each subject, with α=0.001. The resulting random effects level criterion of 0.0074 was then applied to the 80-channel theta phase dissimilarity index value for each subject (i.e.,0.0180, 0.0149, 0.0118, 0.01093, 0.0096, 0.0094, 0.0080, 0.0074, 0.0052, 0.0046, 0.0023, 0.0017, 0.0014) to select those subjects (7 in total) exhibiting significant phase dissimilarity reflective of cross-trial phase coherence. For each selected subject, the analyses were performed on the data from the auditory channel exhibiting the greatest theta phase dissimilarity index value for that subject (auditory channel quadrant locations: 5 left posterior, 2 right posterior). Thus, both subject and channel selection were used to focus the analysis on response data that exhibited the most stimulus-differentiated theta phase patterns, consistent with the presence of a robust phase-locked response in the theta band. The frequency analysis range had an upper limit of 50 Hz such that only frequencies likely to reflect phase-locked responses to speech stimuli were examined.

The first part of the analysis investigated differences in the amplitude of the response data between the pre- and post-stimulus periods. For each subject, the 4500 ms of epoch data retained for each trial of every sentence (360 trials in total) was divided into nine 500 ms segments. Amplitude spectra for the segments of each individual trial were obtained via a 500 point fast-Fourier transform and then averaged over all trials to obtain a mean amplitude spectrum for each segment. The mean amplitude spectrum for the pre-stimulus response (1–1000 ms) was computed by averaging the mean spectra obtained for the first two segments. Similarly, the mean amplitude spectrum for the post-stimulus response (1001–4500 ms) was computed by averaging the mean spectra for segments 3 through 9. The post-stimulus response was also broken down into the onset response (1001–1500 ms) with an amplitude spectrum corresponding to the mean amplitude spectrum of segment 3, and the ongoing response (1501–4500 ms) with an amplitude spectrum computed by averaging the mean spectra for segments 4 through 9. In addition, the ongoing response was broken down into successive one second time periods by averaging the mean spectra for segments 4 and 5, 6 and 7, and 8 and 9, respectively. Percent changes in the mean amplitude of the post-stimulus response relative to the prestimulus response were determined for all post-stimulus segments described above. Grand averages for each of the segments were also obtained by averaging across the subject results. In addition, the mean prestimulus amplitude spectrum for each subject was normalized by dividing by the sum of amplitude values in the frequency range 2≤f≤50, and then averaged across subjects to obtain a grand average.

For each subject, the evoked response for each sentence was computed by averaging the 4500 ms epoch data across the 120 trials. Amplitude spectra for the prestimulus, onset and ongoing periods of the evoked response were obtained by applying a fast Fourier transform (500 points) to successive 500 ms segments and then averaging the results over sentences and the segment groups associated with the response periods as described above. Evoked response amplitude as a percent of the mean prestimulus amplitude was then computed and the results averaged across subjects to determine the grand average. Although the evoked response for the prestimulus period should be zero at all frequencies when computed over an infinite number of trials, it may be greater than zero when computed over 120 trials. To find the expected value of the evoked response for the prestimulus period when computed over 120 trials for comparison with the actual results, prestimulus activity was simulated as 1000 ms of white noise, generated in sets of 120 trials representing data for seven subjects presented with three stimuli. The simulated prestimulus data was then subjected to the same evoked response analysis as the actual prestimulus data to produce the grand average evoked response amplitude as a percent of mean prestimulus amplitude. This process was repeated 1000 times and the results averaged across both repetitions and frequency bins from 2 to 50 Hz to determine the expected value.

The second part of the analysis examined the relationship between phase and amplitude over the course of the response using a spectrogram analysis like that utilized in the power and phase dissimilarity analysis, but with a finer-grained time scale. For each subject, a spectrogram of the 4500 ms epoch obtained for each trial was computed based on a 500 ms Hamming window with 20 ms steps. The mean prestimulus amplitude across trials for sentence k frequency bin f was computed as:

where Afktn is the amplitude for frequency bin f at time bin t in trial n, N is total trials (120) and T is the number of time bins reflecting only the prestimulus portion of the response (26). Mean differences in amplitude relative to the mean prestimulus amplitude (percent) for sentence k were then computed for each frequency f and time bin t as:

Cross-trial phase coherence as a function of frequency and time was computed as:

where θfktn is the phase for frequency bin f at time bin t for trial n of sentence k. Within-subject means for relative amplitude change and phase coherence were found by averaging across sentences. Grand average time–frequency distributions of amplitude change and phase coherence were then determined by averaging across the subject means.

The relationship between phase coherence and amplitude change relative to mean prestimulus amplitude in the theta band was examined using the pool of 8442 phase coherence–amplitude change data points obtained for all subjects (7), sentences (3), and time bins (201) for the 4 Hz and 6 Hz frequency bins as described above. First, the theoretical relationship between phase coherence and amplitude change was derived for a “signal plus background” model in which theta-band responses were simulated as the sum of a 500 ms phase-locked signal and a 1000 ms background oscillation of random phase (both represented as 4 Hz sine waves) for sets of 120 trials. Simulated background data, corresponding directly to the empirical prestimulus data for the 4 Hz frequency bin (7 subjects×3 stimuli× 26 time points×120 trials), were generated by adjusting the amplitude of the background oscillation relative to its mean value to match the empirical data. Signal amplitudes (seven linearly increasing values plus zero) were chosen to produce phase coherence in the range observed experimentally, i.e., 0 to 0.6. A total of 546 sets (7subjects×3 stimuli×26 time points) of 120 trials were generated for each signal amplitude value. Then phase coherence and amplitude change were computed across each trial set using the same methodology previously applied to the empirical data. Phase coherence and amplitude change values were averaged across each 546 data point cluster produced for a given signal level to produce the theoretical model data points. Next, comparable estimates of the empirical amplitude change–phase coherence relationship were derived from the pooled data by binning the empirical data points falling within specific phase coherence and amplitude change boundaries and computing the mean phase-coherence and amplitude change for each bin containing at least 10 points. Bin boundaries were derived as lines through the theoretical model data points with slopes equal to the inverse slope of the linear regression fit to each simulated data cluster resulting from a non-zero additive signal (a linear fit was also applied to this set of slopes to smooth slope progression as a function of additive signal level). Estimates of the amplitude change–phase coherence relationship were computed for the entire epoch period and also for successive time periods 0 (prestimulus), 1 (onset), and 2 through 4 associated with time bin subsets 1–26, 27–76, 77–126, 127–176, and 177–201.

Statistical analysis

Bootstrap resampling (10,000 repetitions) based on the bias-corrected and accelerated method (Efron, 1987) was used to establish confidence limits on all grand average results as determined by specified α values (α values associated with particular results are noted in the Results section). Positivity (negativity) in a grand average result was considered significant if both the upper and lower confidence limits were positive (negative) for the specified α level.

Results

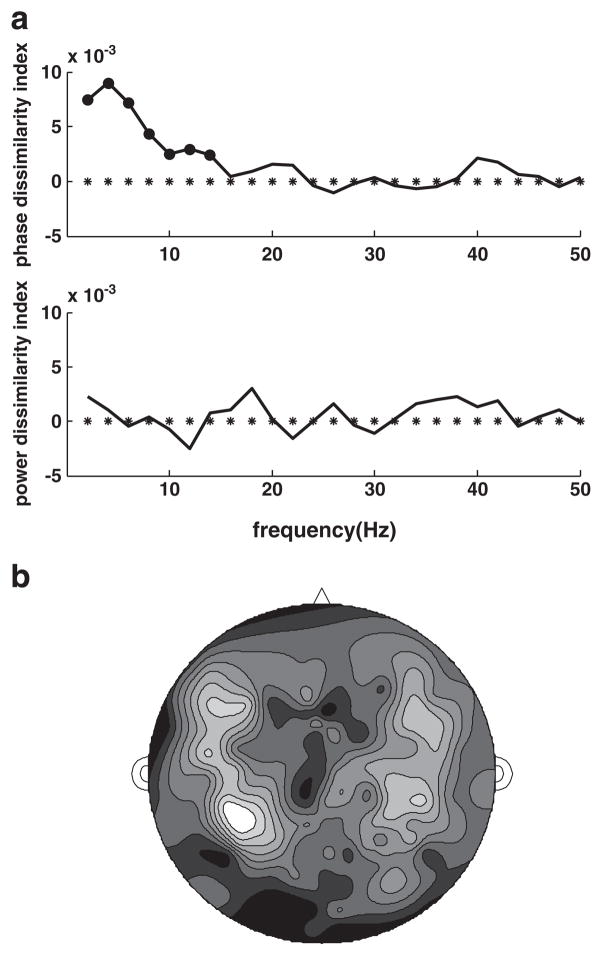

Power and phase dissimilarity

The grand average phase dissimilarity index for the auditory channel mean (80 channels) is significantly greater than zero for frequencies below 15 Hz (bootstrap resampling, α=0.02, p<0.01) and is particularly prominent for delta–theta band frequencies (1–7 Hz), peaking at 4 Hz (Fig. 2a). The power dissimilarity index is not significantly different from zero for any frequency. The topography of the grand average phase dissimilarity for the theta band (Fig. 2b) demonstrates that theta phase dissimilarity is most evident in the auditory channel set and is consistent with bilateral sources located in auditory cortex (see Fig. 1 for comparison). These results are consistent with earlier findings (Howard and Poeppel, 2010; Luo and Poeppel, 2007; Luo et al., 2010) showing that responses to attended spoken sentences in MEG channels reflecting activity in the auditory cortex can be discriminated based on differences in low frequency (<15 Hz) phase but not power patterns present in single-trial data. As observed previously, phase discrimination is strongest in the theta band on average, peaking at 4 Hz, implying that theta band activity is robustly phase-locked to stimulus features that differ in their timing across stimuli.

Fig. 2.

a) Grand averages for phase and power dissimilarity index spectra based on 80 auditory channels. Circle markers indicate results that are significantly greater (less) than zero (p<0.01). b) Topography of grand-average phase dissimilarity in the theta band.

Amplitude and phase modulation

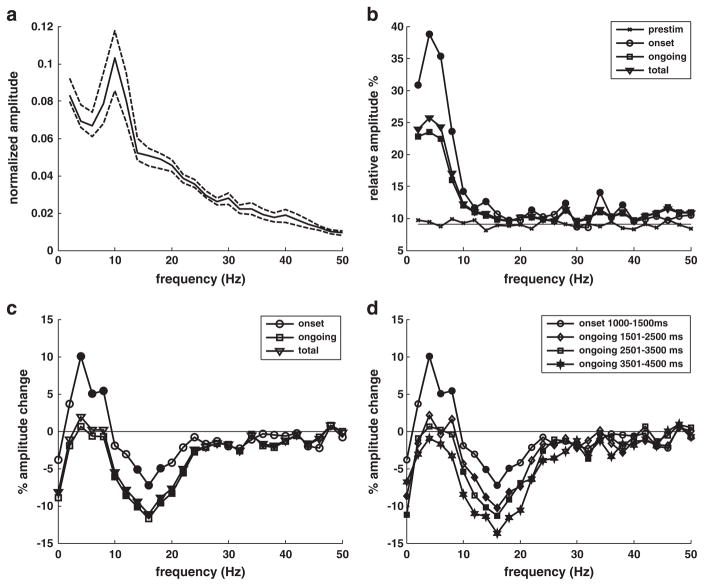

The amplitude and phase modulation analyses that follow were conducted on the response data exhibiting the strongest theta-band phase-locked activity (top channel for the top seven subjects), identified on the basis of the theta phase dissimilarity results as described in Material and methods. The grand average of the normalized amplitude spectra for the prestimulus activity (Fig. 3a) shows the decline with increasing frequency characteristic of cerebral oscillatory activity as well as a prominent peak at ~10 Hz associated with an eyes-closed state of alert readiness (Dockree et al., 2007; Hari and Salmelin, 1997). As expected, the grand average spectrum for the evoked response as a percent of mean prestimulus amplitude shows a peak in the theta band consistent with robust phase-locked activity in the 3–7 Hz frequency range (Fig. 3b). Evoked activity significantly greater than that expected by chance (bootstrap resampling, α=0.02, p<0.01) can be observed consistently at frequencies below 15 Hz for both the onset and ongoing periods. Significant evoked activity is largely absent in the beta band (12–30 Hz) but is observed at low gamma frequencies for both the onset (<40 Hz) and ongoing (<50 Hz) responses.

Fig. 3.

a) Grand average of normalized mean prestimulus amplitude (1–1000 ms) for selected subjects and channels. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence levels. b) Grand average of evoked response amplitude as a percent of mean prestimulus amplitude. Solid line without markers shows expected value of prestimulus evoked response levels based on Monte Carlo simulation. c) Grand average of percent change in amplitude relative to mean prestimulus amplitude. Solid markers indicate values that are significantly different from zero for p<0.01. Total post-stimulus response includes both onset (1001–1500 ms) and ongoing response (1501–3500 ms). d) Same as c but with post-stimulus results broken down into successive periods.

The grand average results for the change in amplitude in the post-stimulus response relative to mean prestimulus amplitudes show a significant increase (bootstrap resampling, α=0.02, p<0.01) for frequencies in the 3–9 Hz range with a 4 Hz peak during onset (1–500 ms) but not during the ongoing (501–3500 ms) response (Fig. 3c). A significant decrease in amplitude is observed for frequencies in the 13–19 Hz range for the onset response, peaking at 16 Hz. The ongoing response displays a similar amplitude decrease, with significant decreases extending from 9 to 25 Hz and also appearing at some frequencies between 30 and 40 Hz. Amplitude changes for the total response are quite similar to those for the ongoing period, which constitutes most of the total. Results for sub-periods of the ongoing response (Fig. 3d) suggest that amplitude change for frequencies below ~30 Hz consistently moves in a negative direction over the course of the response.

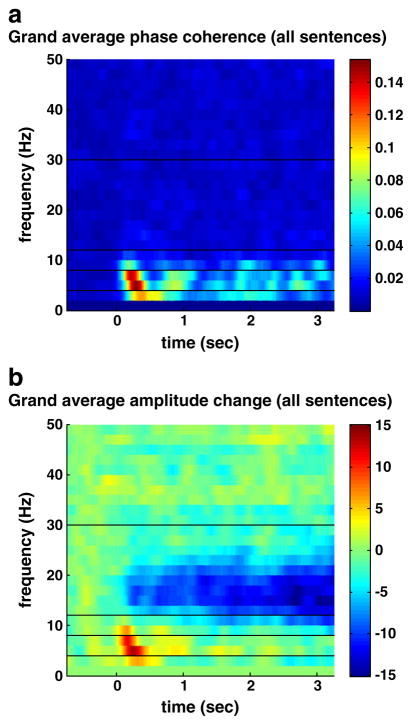

The grand average time–frequency distribution for phase coherence (Fig. 4a) indicates that post-stimulus phase coherence is mainly confined to frequencies below 15 Hz peaking in the theta band at ~4 Hz. The grand average time–frequency distribution for the change in amplitude relative to mean prestimulus amplitude (Fig. 4b) results are consistent with the results from the more coarse-grained time analysis discussed previously (Fig. 3). The time–frequency distributions for phase coherence and amplitude suggest that at low frequencies, particularly in the theta band, phase coherence and amplitude are co-modulated, with points of co-occurring increases appearing not only at onset but also throughout the post-stimulus period.

Fig. 4.

Grand average time–frequency distributions across all sentence stimuli and subjects. a) Phase coherence across 120 trials for each stimulus. b) Percent change in amplitude relative to mean prestimulus level averaged over 120 trials for each stimulus.

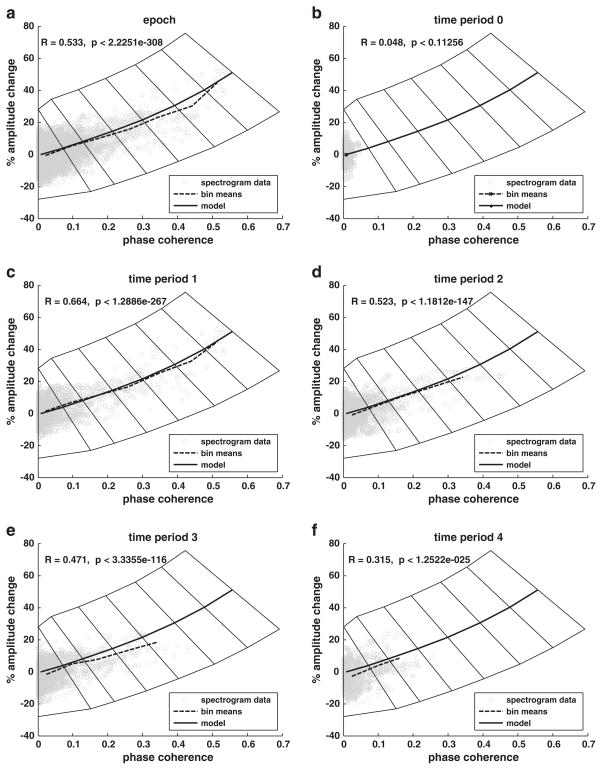

Co-modulation of phase coherence and amplitude in the theta band was investigated by examining amplitude change as a function of phase coherence using the subject time–frequency distribution data obtained for each sentence (Fig. 5). The data covering the full 4500 ms epoch (Fig. 5a) exhibits a significant positive correlation (R=0.533, p<0.001) between amplitude change and phase coherence. Furthermore, the empirical function derived from the binned data is quite similar to the modeled function derived from simulated data constructed from the addition of phase-locked responses to random-phase background activity. The data subset restricted to the prestimulus period (Fig. 5b) exhibits minimal phase coherence and no significant correlation between amplitude change and phase coherence (R=0.048, p<0.113) as expected in the absence of a stimulus. Data subsets covering successive post-stimulus periods (Figs. 5b–f) reveal that the amplitude–phase coherence correlation decreases over time but remains highly significant even for the last post-stimulus period (period 1: R=0.664, p<0.001, period 2: R=0.523, p<0.001, period 3: R=0.471, p<0.001, period 4: R=0.315, p<0.001). The decreasing correlation appears to be associated with decreasing phase coherence and amplitude change over time (see also Fig. 6a).

Fig. 5.

Change in amplitude versus phase coherence for individual subject/stimulus time–frequency distribution data points for the theta band (gray circles). Dashed line connects bin means based on bin boundaries represented as polygons surrounding the solid center line. The solid center line represents the theoretical amplitude change–phase coherence relationship based on the pure additive model. a) Data for entire 4500 ms epoch. b–f) Data for successive time periods across epoch.

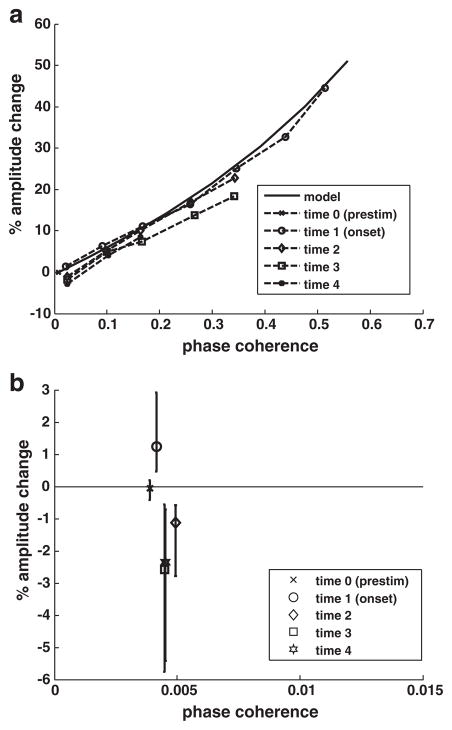

Fig. 6.

a) Composite plot of the amplitude change–phase coherence relationship across successive time periods based on bin means. b) For successive time periods, mean amplitude change for data points for which phase coherence <0.01.

The relationship between phase coherence and amplitude changes remains similar to that predicted by the model for all time periods but with a reduction in amplitude relative to phase coherence after the onset period that appears to increase slightly with time (Fig. 6a). Mean amplitude change and phase coherence for data points with phase coherence values close to zero (<0.01) show mean amplitude change ≈ 0.0 during the prestimulus period, as expected (Fig. 6b). During the onset period, amplitude change is significantly greater than zero (p<0.025) with a mean of 1.2%. For later periods, amplitude change is significantly less than zero (p<0.025) with means of −1.1%, −2.6%, and −2.4% for periods 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Discussion

Summary

The results support the hypothesis that theta-band phase coherence and amplitude are co-modulated across MEG auditory channel responses to an attended spoken sentence in a manner that is consistent with the addition of phase-locked theta activity to randomly-phased background activity. Such co-modulation would not be expected if the stimulus elicited only pure phase-resetting of the ongoing theta oscillation, which would produce increases in phase coherence without concomitant increases in amplitude. The earlier finding that attended spoken sentences could be discriminated on the basis of theta-band phase, but not power, patterns present in single-trials (Luo and Poeppel, 2007) seemed to point to a pure phase-setting response to the stimuli. However, subsequent modeling demonstrated that this result is consistent with an additive phase-locked response (Howard and Poeppel, 2010). The co-modulation results presented here, derived from data that clearly replicate previous phase/power discrimination findings, provide empirical evidence that additive phase-locked activity is not only present in the response, but is, in fact, the predominant factor underlying phase coherence and the associated phase-pattern discrimination effects.

Event-related amplitude change

During the onset response, we observed a significant increase in post-stimulus amplitude relative to the prestimulus baseline in the 3–9 Hz range peaking at 4 Hz. This result is consistent with the findings on post-stimulus amplitude changes in the EEG response to single tones and glides (Cacace and McFarland, 2003) and the MEG response to single tones (Mäkinen et al., 2005). The amplitude increase appears to be mainly attributable to phase-locked activity, with non-phase-locked activity contributing approximately 1.2% to the total 7.7% amplitude increase observed for the 4 and 6 Hz bins (bin average).

During the onset response, we also observed a significant decrease in lower beta-band amplitude that became more pronounced for the ongoing response, extending into the upper alpha and beta bands. This may be related to the motor response that was required following each stimulus presentation. Event-related amplitude decreases (event-related desynchronization) at these frequencies have been observed previously in association with voluntary movement starting about 2 s prior to the movement (Leocani et al., 1997; Pfurtscheller and Lopes da Silva, 1999; Stancák and Pfurtscheller, 1996), which could account for the amplitude decreases observed during the ongoing response. Furthermore, this beta suppression is succeeded by amplitude increases (event-related synchronization) that peak approximately 1 s after movement completion (Pfurtscheller and Lopes da Silva, 1999). Such increases would be reflected in the prestimulus amplitudes used as the baseline in our analysis, which could explain the amplitude decreases relative to baseline observed during the onset response. However, amplitude suppression in this same frequency range has been observed in electrocorticographical (ECoG) responses to spoken syllables recorded in the mid-superior temporal gyrus (STG) during a passive listening task (Edwards et al., 2009), suggesting that the suppression may be attributable, at least partially if not totally, to the auditory stimulus. In addition, the overall shape of the change in amplitude as a function of frequency curve obtained in our experiment closely matches the post-stimulus LFP (local field potential) power enhancement curves obtained in primary auditory cortex of macaques listening to natural auditory stimuli with robust enhancement at theta frequencies and little or no enhancement at lower beta frequencies (Chandrasekaran et al., 2010). This pattern suggests that the MEG data may reflect the summation of power enhancement attributable to phase-locked activity in auditory cortex (concentrated mainly in the theta band) and broadband power suppression in background activity induced by the auditory stimulus. If so, then the apparent lower-beta power suppression would actually reflect the absence of stimulus-evoked power enhancement in lower-beta band relative to adjacent frequency bands rather than suppression concentrated in this band.

Additive activity versus phase-resetting

Several EEG studies have sought evidence of additive phase-locked activity in response to auditory stimuli by looking for coincidental, statistically-significant increases in phase coherence and amplitude relative to prestimulus levels. Jervis et al. (1983) analyzed the responses to a single tone presented 64 times each at two intensity levels to three subjects (inter-tone interval unknown but ≥924 ms). They found significant phase coherence increases at ~1–13 Hz that were consistently significant across stimulus levels and subjects for the 1–7 Hz range. Furthermore, they observed significant amplitude increases at ~1–7 Hz that were consistently significant across stimulus levels and subjects for the 3–5 Hz range. Jansen et al. (2003) utilized pairs of identical tone bursts with an intra-pair interval of ~500 ms and an inter-pair interval ≥8 s, analyzing 25 responses from each of 20 subjects. They found significant phase coherence but no significant amplitude increase at ~2–8 Hz for both tones. In a similar study, Fuentemilla et al. (2006) utilized stimulus trains consisting of three identical tone bursts with an intra-train interval of 584 ms and an inter-train interval of 30 s, analyzing 54 to 88 (mean 71) responses in each of 16 subjects. They found a significant increase in phase coherence for all tones at ~3–16 Hz (analysis did not extend to frequencies below 3 Hz), accompanied by a significant increase in amplitude for the first tone only. The phase coherence and amplitude increases were most prominent at ~3–7 Hz. Despite differences in stimuli and methods, these studies were consistent in finding significant phase coherence in the response to the first (or single) tone in the stimulus for theta band frequencies (3–7 Hz). Furthermore, two of the studies found significant amplitude increases in the theta band response to the first tone, consistent with amplitude increases observed in the MEG response to a single tone (Mäkinen et al., 2005). The failure to find a significant increase in theta amplitude in the response to the first tone by Jansen et al. (2003) is likely attributable to the small number of responses per subject analyzed in that study, given that increases in phase coherence resulting from the addition of a small amount (relative to background) of phase-locked activity are detectible over just a few responses while increases in amplitude are not (Howard and Poeppel, 2010). Similarly, the extended range over which significant increases in phase coherence and amplitude were observed in the response to the first tone in the Fuentemilla et al. (2006) investigation may be attributable to the larger number of responses per subject analyzed in that study, which would provide more sensitivity to the weaker effects found at higher frequencies.

Because our study used continuous speech rather than discrete, repeated tones as stimuli, there is not an exact correspondence between our results and those just described. However, the response to a first/single tone can be considered an onset response to an auditory stimulus and, therefore, comparable to the onset response for speech stimuli. In addition, the envelopes of both the tone trains and the speech signals are dominated by slow modulations such that the responses to the second and third tones may be comparable to the ongoing response for speech stimuli. We observed that, like the response to the first/single tones, the onset response to speech exhibited significant amplitude increase for theta frequencies. Further, like the response to second and third tones, the ongoing response exhibited no significant amplitude increase.

Collectively, these findings suggest that additive power in the theta band contributes to the onset, but not to the ongoing, portion of the response to auditory stimuli containing low frequency modulations of the envelope. Thus, they support the view that enhanced phase coherence during the ongoing period is attributable to pure phase-resetting. However, the co-modulation results contradict this conclusion, indicating that even for the ongoing response, amplitude and phase coherence co-vary in a manner consistent with the presence of additive activity in the theta band. Specifically, both mean amplitude and phase coherence decline during the ongoing response, while crucially, transient phase coherence increases continue to be reliably accompanied by the transient amplitude increases predicted by the additive activity model.

Although the theta-band phase coherence observed in the MEG response to speech cannot be explained as pure phase-resetting of the ongoing theta oscillation present in the prestimulus activity, this does not imply that phase-resetting plays little or no role in the neuronal response. On the contrary, additive activity may reflect not only additional or stronger neuronal activity but also the phase alignment of multiple theta oscillations arising in somewhat different locales that contribute to the composite ongoing theta oscillation. Such phase-resetting would increase the amplitude of the theta oscillation in the post-stimulus response (on average) by reducing cancellation effects associated with phase differences among the reset oscillations (Sauseng et al., 2007; Telenczuk et al., 2010). Differentiation of the possible sources of additive activity requires information on neuronal activity at a granularity that is not, in principle, accessible in MEG/EEG data, which reflect the composite activity of large neuronal populations (Telenczuk et al., 2010). However, more fine-grained views of neuronal activity in response to auditory stimuli obtained via intra-cortical electrodes situated in the primary auditory cortex of awake macaques also found robust theta-band power enhancement in local field potential response (Chandrasekaran et al., 2010) and provided evidence that inhibitory responses to tones involve mainly phase resetting in the delta, theta, and gamma bands, while excitatory responses involve both additive and phase reset activity (O’Connell et al., 2011).

Changes in background activity

Our results are largely explained as evoked activity effects. However, we did observe changes in non-phase-locked theta-band (background) activity that suggest the presence of induced activity effects as well. Specifically, we observed small but significant amplitude decreases during the ongoing response periods that could reflect either a slight suppression of non-phase-locked theta activity following the onset response or the desynchronization of multiple oscillations contributing to the composite background oscillation. Reductions in non-phase-locked activity would shift the amplitude–phase coherence relationship predicted by the additive activity model (as depicted in Fig. 6a) downward and to the right, consistent with our observations for the ongoing periods.

Stimulus- and attention-related considerations

The use of attended speech as stimuli allowed us to readily relate the findings of this investigation to our earlier work on phase dissimilarity effects. However, we have no principled reason to suppose that our findings are specific to the processing of speech or attended stimuli. Indeed, we hypothesize that the co-modulation of theta band phase coherence and mean amplitude in the low frequency response to speech reflects the processing of acoustic features associated with low frequency modulations of the stimulus envelope and are produced by mechanisms that respond to such features in any auditory stimulus. We further hypothesize that attention serves to increase both theta band phase coherence and mean amplitude levels but does not fundamentally alter the co-modulation relationship rooted in these mechanisms.

With respect to stimulus type, our hypothesis is consistent with our earlier finding of robust theta band phase discrimination for time-reversed speech stimuli (Howard and Poeppel, 2010). This result demonstrated that stimuli that are similar to speech in their spectral–temporal characteristics, but that do not involve speech comprehension, produce the same sort of stimulus-driven theta band phase patterns as speech stimuli. Our hypothesis also finds support in a study that examined CSD (current source density) and LFP (local field potential) responses in the rat auditory cortex (A1) to non-naturalistic stimuli, namely, rock music and 1/f distributed random dynamic tone complexes (Szymanski et al., 2011). This study found that for such stimuli, stimulus-dependent phase information is maximal in low frequency (<16 Hz) LFP responses, just as was observed for naturalistic stimuli that include vocalizations (Chandrasekaran et al., 2010; Kayser et al., 2009). Furthermore, Szymanski et al. discovered that the phase-locked LFP responses originate in transient CSD “events”, time-locked to the stimulus, that occur at a frequency of ~2–4 Hz, which is near the peak of phase discrimination for speech. Such convergence of phase-related response characteristics across stimulus types suggests that the response to non-speech stimuli will exhibit the same phase coherence and mean amplitude co-modulation as was observed for speech; however, further investigation is required to determine the validity of this prediction.

With respect to attention, our hypothesis is consistent with findings on the effects of attention on the EEG response to speech (Kerlin et al., 2010). Utilizing methods conceptually similar to, but analytically distinct from, those of Luo and Poeppel (2007), this study confirmed that attended spoken sentences can be robustly distinguished based on phase-locked responses at lower frequencies, with discrimination performance peaking in the theta band (4–8 Hz). Kerlin et al. further discovered that selective attention to a particular stimulus of a simultaneously-presented stimulus pair produces gains in discrimination performance compared with that observed for the single-stimulus, attended condition. The gain was statistically significant for the theta band response. The results demonstrate that selective attention increases discrimination performance that depends on phase coherence but does not fundamentally alter the frequency-related discrimination profile. It seems reasonable to conjecture that task-related attention to a single stimulus, which is known to enhance the auditory evoked response over that observed for the passive listening condition (Keating and Ruhm, 1971), produces gain effects of the same nature. Thus, we would expect unattended stimuli to produce weaker phase coherence than attended stimuli, but not phase coherence increases in the absence of mean amplitude increases, in conflict with our current findings. Verification of this contention requires a replication of our phase coherence–mean amplitude analysis with response data obtained using unattended stimuli.

Conclusion

Based on our analysis of phase coherence–amplitude co-modulation, the theta-band post-stimulus activity associated with attended spoken sentences, as observed at an MEG channel over auditory cortex, seems best explained as the addition of a phase-locked response to non-phased-locked background activity. The exact relationship of the phase-locked response to the auditory signal is not known but, conceivably, can be characterized as a series of theta-dominant responses produced in correspondence to the low frequency (≤8 Hz) modulations of the acoustic envelope (Aiken and Picton, 2008; Howard and Poeppel, 2010). If this is the case, then the phase-locked theta-band response could represent a segmenting of the near-continuous acoustic signal into individual elements, approximately 150–300 ms in length, which provide the basis for speech, melody, rhythm, and prosodic analysis. However, the amplitude decrease over the course of the response to the sentence stimulus observed in this study suggests that the theta-band response reflects more than the serial processing of elements individuated within the signal by salient acoustic edges. One possibility is that the amplitude reduction signifies increasing response selectivity such that the response for a particular element represents not only the element itself but also the pattern of elements that precede it, that is, it represents the element preceded by a predictive context. Thus, the phase-locked theta-band response to an auditory stimulus could reflect not only signal segmentation activities but also pattern integration activities associated with the sequential processing of the acoustic input.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Ding and L. Arnal for valuable comments, J. Walker for excellent technical assistance, and H. Luo for analytical materials. The work is supported by NIH 2R01DC05660 to D. Poeppel.

Footnotes

Although systematic post-stimulus amplitude change is not readily evident in individual trials due to background amplitude variability (Arieli et al., 1996) and cancellation effects for additive activity that is out-of-phase with background activity (Howard and Poeppel, 2010; Mäkinen et al., 2005; Mazaheri and Picton, 2005), it can be observed by averaging pre- and post-stimulus amplitudes over many trials and comparing the results.

References

- Abrams DA, Nicol T, Zecker S, Kraus N. Right-hemisphere auditory cortex is dominant for coding syllable patterns in speech. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3958–3965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0187-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi Y, Shimogawara M, Higuchi M, Haruta Y, Ochiai M. Reduction of nonperiodic environmental magnetic noise in MEG measurement by continuously adjusted least square method. IEEE Trans Appl Supercond. 2001;11:669–672. [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar E, Nagarajan S, Ahissar M, Protopapas A, Mahncke H, Merzenich MM. Speech comprehension is correlated with temporal response patterns recorded from auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13367–13372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201400998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken SJ, Picton TW. Human cortical responses to the speech envelope. Ear Hear. 2008;15:139–157. doi: 10.1097/aud.0b013e31816453dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli A, Sterkin A, Grinvald A, Aertsen A. Dynamics of ongoing activity: explanation of the large variability in evoked cortical responses. Science. 1996;273:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacace AT, McFarland DJ. Spectral dynamics of electroencephalographic activity during auditory information processing. Hear Res. 2003;176:25–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran C, Turesson HK, Brown CH, Ghazanfar AA. The influence of natural scene dynamics on auditory cortical activity. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13919–13931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3174-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David O, Kilner JM, Friston KJ. Mechanisms of evoked and induced responses in MEG/EEG. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1580–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H. Enhancement of evoked cortical potentials in humans related to task requiring decision. Science. 1964;145:182–183. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3628.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cheveigné A, Simon JZ. Denoising based on time-shift PCA. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;165:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Srinivasan R. Semantic and acoustic analysis of speech by functional networks with distinct time scales. Brain Res. 2010;1346:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockree PM, Kelly SP, Foxe JJ, Reilly RB, Robertson IH. Optimal sustained attention to the spectral content of background EEG activity: greater ongoing tonic alpha (approximately 10 Hz) power supports successful phasic goal activation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:900–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E, Soltani M, Kim W, Dalal SS, Nagarajan SS, Berger MS, et al. Comparison of time–frequency responses and the event-related potential to auditory speech stimuli in human cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:377–386. doi: 10.1152/jn.90954.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Dietl T, Grunwald T, Kurthen M, Klaver P, Trautner P, Schaler C, Elger CE, Fernández G. Neural bases of cognitive ERPs: more than phase reset. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1595–1604. doi: 10.1162/0898929042568514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentemilla Ll, Marco-Pallarés J, Grau C. Modulation of spectral power and of phase resetting of EEG contributes differentially to the generation of auditory event-related potentials. Neuroimage. 2006;30:909–916. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross MM, Begleite H, Tobin M, Kissin B. Auditory evoked response comparison during counting clicks and reading. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1965;18:451–454. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(65)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T. A neuromagnetic analysis of the mechanism for generating auditory evoked fields. Int J Psychophysiol. 2005;56:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanslmayr S, Klimesch W, Sauseng P, Gruber W, Doppelmayr M, Freunberger R, Pecherstorfer T, Birbaumer N. Alpha phase reset contributes to the generation of ERPs. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari R, Salmelin R. Human cortical oscillations: a neuromagnetic view through the skull. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:44–49. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MF, Poeppel D. Discrimination of speech stimuli based on neuronal response phase patterns depends on acoustics but not comprehension. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:2500–2511. doi: 10.1152/jn.00251.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen BH, Agarwal G, Hegde A, Boutros NN. Phase synchronization of the ongoing EEG and auditory EP generation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jervis BW, Nichols MJ, Johnson TE, Allen E, Hudson NR. A fundamental investigation of the composition of auditory evoked potentials. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1983;30:43–50. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1983.325165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Montemurro MA, Logothetis NK, Panzeri S. Spike-phase coding boosts and stabilizes information carried by spatial and temporal spike patterns. Neuron. 2009;61:597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating LW, Ruhm HB. Some observations on effects of attention to stimuli amplitude of acoustically evoked response. Audiology. 1971;10:177–184. doi: 10.3109/00206097109072556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin JR, Shahin AJ, Miller LM. Attentional gain control of ongoing cortical speech representations in a “cocktail party”. J Neurosci. 2010;30:620–628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3631-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leocani L, Toro C, Manganotti P, Zhuang P, Hallet M. Event-related coherence and event-related desynchronization/synchronization in the 10 Hz and 20 Hz EEG during self-paced movements. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;104:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(96)96051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Poeppel D. Phase patterns of neuronal responses reliably discriminate speech in human auditory cortex. Neuron. 2007;54:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Liu Z, Poeppel D. Auditory cortex tracks both auditory and visual stimulus dynamics using low-frequency neuronal phase modulation. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(8):e1000445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütkenhöner B, Steinsträter O. High-precision neuromagnetic study of the functional organization of the human auditory cortex. Audiol Neurootol. 1998;3:191–213. doi: 10.1159/000013790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeig S, Westerfield M, Jung TP, Enghoff S, Townsend J, Courchesne E, Sejnowski TJ. Dynamic brain sources of visual evoked responses. Science. 2002;295:690–694. doi: 10.1126/science.1066168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen V, Tiitinen H, May P. Auditory event-related responses are generated independently of ongoing brain activity. Neuroimage. 2005;24:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaheri A, Picton TW. EEG spectral dynamics during discrimination of auditory and visual targets. Cogn Brain Res. 2005;24:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell MN, Falchier A, McGinnis T, Schroeder CE, Lakatos P. Dual mechanism of neuronal ensemble inhibition in primary auditory cortex. Neuron. 2011;69:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G, Lopes da Silva FH. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1842–1857. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton TW, Hillyard SA. Human auditory evoked-potentials. II Effects of attention. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1974;36:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(74)90156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton TW, Hillyard SA, Galambos R, Schiff M. Human auditory attention —central or peripheral process. Science. 1971;173:351–353. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3994.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield JH. Evoked cortical response enhancement and attention in man: a study of responses to auditory and shock stimuli. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1965;19:470–475. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(65)90185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Gruber WR, Hanslmayr S, Freunberger R, Dopplemayr M. Are event-related potential components generated by phase resetting of brain oscillations? A critical discussion. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1435–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers BM, Beagley HA, Henshall WR. The mechanism of auditory evoked EEG responses. Nature. 1974;247:481–483. doi: 10.1038/247481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AS, Bressler SL, Knuth KH, Ding M, Mehta AD, Ulbert I, Schroeder CE. Neural dynamics and fundamental mechanisms of event-related brain potentials. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:476–483. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spong P, Haider M, Lindsley DB. Selective attentiveness and cortical evoked responses to visual and auditory stimuli. Science. 1965;148:395–397. doi: 10.1126/science.148.3668.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancák A, Jr, Pfurtscheller G. Event-related desynchronisation of central beta rhythms in brisk and slow self-paced finger movements of dominant and nondominant hand. Cogn Brain Res. 1996;4:171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(96)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski FD, Rabinowitz NC, Magri C, Panzeri S, Schnupp JWH. The laminar and temporal structure of stimulus information in the phase of field potentials of auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15787–15801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1416-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenczuk B, Nikulin VV, Curio G. Role of neuronal synchrony in the generation of evoked EEG/MEG responses. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:3557–3567. doi: 10.1152/jn.00138.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]