Summary

The cytochrome bc1 complex (bc1) is the mid-segment of the cellular respiratory chain of mitochondria and many aerobic prokaryotic organisms; it is also part of the photosynthetic apparatus of non-oxygenic purple bacteria. The bc1 complex catalyzes the reaction of transferring electrons from the low potential substrate ubiquinol to high potential cytochrome c. Concomitantly, bc1 translocates protons across the membrane, contributing to the proton-motive force essential for a variety of cellular activities such as ATP synthesis. Structural investigations of bc1 have been exceedingly successful, yielding atomic resolution structures of bc1 from various organisms and trapped in different reaction intermediates. These structures have confirmed and unified results of decades of experiments and have contributed to our understanding of the mechanism of bc1 functions as well as its inactivation by respiratory inhibitors.

Keywords: cytochrome bc1 complex, bifurcated electron flow, mechanism of ubiquinol oxidation, crystal structure, control of ISP domain movement

1. Functions of the cyt bc1 complex

Ubiquinol cytochrome c oxidoreductase, commonly referred to as complex III or the cytochrome bc1 complex (cyt bc1 or bc1), is a multifunctional, oligomeric membrane protein complex localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes or the cytoplasmic membrane of prokaryotic organisms. This complex is an integral part of the cellular respiratory chain, contributing to the generation of electrochemical potential. Cyt bc1 is also an essential part of the photosynthetic apparatus in purple bacteria, reducing cyt c2 and returning it to the photosynthetic reaction center for oxidation. In plants, bc1 complexes show integrated mitochondrial processing peptidase activity for cleavage of mitochondrial targeting signal peptides. Cyt bc1 complexes have also been associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Alteration of bc1 either by mutagenesis or by chemical treatment results in changes in function that often lead to devastating consequences.

1.1. Electron-transfer coupled proton-pumping function

The cyt bc1 complex catalyzes the antimycin-sensitive electron transfer (ET) reaction from lipophilic substrate ubiquinol (QH2) to cyt c coupled with proton translocation across the membrane [1]. As a result, for every QH2 molecule oxidized, four protons are deposited to the positive side of the membrane and two molecules of cyt c are reduced. This stoichiometry of the ET reaction is given in the following equation, where QH2 and Q represent lipid-soluble reduced and oxidized ubiquinone, respectively, c3+ and c2+ represent oxidized and reduced cyt c, and H+N and H+P represent protons at the negative and positive side of membrane. The cross-membrane potential thus generated serves as the energy source for various cellular activities such as the production of ATP by ATP synthase.

1.2. Mitochondrial processing peptidase activity

The cyt bc1 complexes from higher organisms also exhibit mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) activity [2]. The MPP activity is readily detected in the purified bc1 complex from plant mitochondria such as spinach; it is inactive (but can be activated with diluted detergents) in the bc1 complex of bovine mitochondria [3]. The MPP activity occurs in the heterodimeric core-1 and core-2 subunits of the mitochondrial bc1 (Mtbc1), which belong to the pitrilysin family of zinc metallopeptidases, whose members include insulin-degrading enzyme and mitochondrial MPP in mammals and in fungi.

1.3. Superoxide generation

Under normal respiration conditions, the ET from QH2 to cyt c catalyzed by the bc1 complex is accompanied by the production of a small amount of superoxide anions presumably through electron leakage to molecular oxygen [4], which increases dramatically when the ET within the bc1 complex is blocked by specific bc1 inhibitors such as antimycin A or when the ET chain becomes over reduced. The most likely site of superoxide anion generation under normal ET conditions is at the site of low-potential cyt b heme (bL heme). Mutations in the cyt b subunit result in not only impaired ET activity but also increased amounts of superoxide anions [5-7]. The role played by the small amount of superoxide anions generated under physiological conditions is not clear but has been speculated to be part of cellular signaling mechanisms [8].

2. Structural organization of cyt bc1 complexes

Complex III was among the earliest discovered ET complexes in mitochondria. Cyt b was detected as early as in 1922 [9] and the first isolation procedure for complex III from bovine heart mitochondria was published in 1962 [10]. An estimated molecular mass of the complex was reported in 1965 [11]. It took another 32 years until the first crystal structure of bovine mitochondrial bc1 (Btbc1) was published in 1997 [12].

2.1. Subunit composition of bc1 in various organisms

The subunit composition of bc1 complexes varies significantly, from three subunits in P. denitrificans and R. capsulatus to as many as eleven subunits in human and bovine mitochondria (Table 1). All bc1 complexes contain three redox subunits: cyt b, having two b-type hemes, a low potential heme bL (Em7 = −90 mV for bacterial bc1 and −30 mV for Btbc1) and a high potential heme bH (Em7 = +50 mV for bacterial bc1 and +100 mM for Btbc1); cyt c1, containing a c-type heme (Em7 = +265 mV for bacterial bc1 and +230 mV for Btbc1); and the iron sulfur protein (ISP), including a high potential 2Fe-2S iron-sulfur cluster (ISC, Em7 = +280 mV for bacterial bc1 and +250 mV for Btbc1). All additional subunits, referred to as supernumerary subunits, have no well-established cellular function except for the subunits core-1 and core-2 in plants, which are metalloproteases, and thus are believed to contribute to the increased stability of these complexes. Indeed, bc1 complexes of eukaryotes carry more supernumerary subunits than those of prokaryotes, consistent with the fact that bc1 complexes of higher organisms are generally more stable [13]. Furthermore, purified complex III contains ubiquinone and various phospholipids [14].

Table 1. Available coordinates of deposited bc1 structures or fragments determined by X-ray crystallography or EM.

| PDB ID |

Orga1 | QP site occupant2 |

Inhibitor Type |

QN site occupant3 |

Reso3 [Å] |

R (free)4 |

No. subunits: found/in vivo |

MW5 (kDa) |

SG | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1RIE | B.T. | - | - | - | 1.5 | ISP-ED | 14.6 | P21 | Iwata [16] | |

| 1SQB | B.T. | Azo | Pm | - | 2.69 | 0.288 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [58] |

| 3L71 | G.G. | Azo | Pm | Q10 | 2.84 | 0.281 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP6 |

| 3L70 | G.G. | Trifloxy | Pm | Q10 | 2.75 | 0.297 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP |

| 1SQP | B.T. | Myx | Pm | - | 2.7 | 0.314 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [58] |

| 1SQQ | B.T. | MOAS | Pm | Q2 | 3.0 | 0.295 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [58] |

| 3L72 | G.G. | Kres | Pm | Q10 | 3.06 | 0.294 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP |

| 3H1K | G.G. | Kres | Pm | Q10 | 3.48 | 0.284 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [108] |

| 3L73 | G.G. | Triaz | Pm | Q10 | 3.04 | 0.293 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP |

| 1L0L | B.T. | Fam | Pf | - | 2.35 | 0.306 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [109] |

| 3L74 | G.G. | Fam | Pf | Q10 | 2.76 | 0.286 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP |

| 2FYU | B.T. | JG144 | Pf | - | 2.26 | 0.283 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [57] |

| 3L75 | G.G. | Fen | Pf | Q10 | 2.79 | 0.275 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry TBP |

| 3H1L | G.G. | Asc | Pf, PN | Asc | 3.21 | 0.295 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [110] |

| 3CWB | G.G. | Croc | Pf | Q10 | 3.51 | 0.319 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [111] |

| 1NU1 | B.T. | NQNO | Pf, PN | NQNO | 3.2 | 0.296 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [109] |

| 1SQV | B.T. | UHDBT | Pf | Q2 | 2.85 | 0.285 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [58] |

| 1P84 | S.C. | HDBT | Pf | Q6 | 2.5 | 0.252 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [24] | |

| 1SQX | B.T. | Stg | Pf | Q2 | 2.6 | 0.281 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [58] |

| 2A06 | B.T. | Stg | Pf | Q10 | 2.1 | 0.258 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [112] |

| 1PP9 | B.T. | Stg | Pf | Q10 | 2.1 | 0.287 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [112] |

| 1PPJ | B.T. | Stg | Pf | Ant | 2.1 | 0.26 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [112] |

| 2BCC | G.G. | Stg | Pf | Q10 | 3.5 | 0.317 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [112] |

| 3BCC | G.G. | Stg | Pf | Ant | 3.7 | 0.321 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [18] |

| 3H1I | G.G. | Stg | Pf | Ant | 3.53 | 0.306 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [110] |

| 3H1J | G.G. | Stg | Pf | Q10 | 3.0 | 0.277 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [18] |

| 1EZV | S.C. | Stg | Pf | Q6 | 2.3 | 0.254 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [19] |

| 1KB9 | S.C. | Stg | Pf | Q6 | 2.3 | 0.249 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [91] |

| 1KYO7 | S.C. | Stg | Pf | - | 2.97 | 0.268 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [87] |

| 3CX5 | S.C. | Stg | Pf | - | 1.9 | 0.263 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [88] |

| 2IBZ | S.C. | Stg | Pf | Q6 | 2.3 | 0.256 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [113] |

| 3CXH | S.C. | Stg | Pf | - | 2.5 | 0.256 | 9 / 10 | 467 | C2 | Hunte [88] |

| 1ZRT | R.C. | Stg | Pf | - | 3.5 | 0.358 | 3 / 3 | 221 | p21 | Berry [20] |

| 2FYN | R.S. | Stg | Pf | - | 3.2 | 0.254 | 3 / 4 | 250 | I4122 | Xia [57] |

| 2QJP | R.S. | Stg | Pf | Ant | 2.6 | 0.277 | 3 / 4 | 250 | I4122 | Xia [21] |

| 2QJK | R.S. | Stg | Pf | Ant | 3.1 | 0.266 | 3 / 4 | 250 | I4122 | Xia [21] |

| 2QJY | R.S. | Stg | Pf | Q2 | 2.4 | 0.251 | 3 / 4 | 250 | I4122 | Xia [21] |

| 2YIU | P.C. | Stg | Pf | - | 2.7 | 0.29 | 3 / 3 | 467 | P21 | Hunte [22] |

| 2YBB | T. T. | Stg | Pf | Q1 | 19.0 | N/A | - | 1,700 | Kiirlbrandt [114] | |

| 1QCR | B.T. | - | - | - | 2.7 | 0.375 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [12] |

| 1BE3 | B.T. | - | - | - | 3.0 | 0.32 | 11 / 11 | 486 | P6522 | Iwata [17] |

| 1BGY | B.T. | - | - | - | 3.0 | 0.36 | 11 / 11 | 486 | P6 5 | Iwata [17] |

| 1L0N | B.T. | - | - | - | 2.6 | 0.297 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [26] |

| 1NTM | B.T. | - | - | - | 2.4 | 0.285 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [27] |

| 1NTZ | B.T. | Q2 | - | Q2 | 2.6 | 0.283 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [27] |

| 1NTK | B.T. | - | - | Ant | 2.6 | 0.27 | 11 / 11 | 486 | I4122 | Xia [27] |

| 1BCC | G.G. | - | - | Q10 | 3.16 | 0.31 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [18] |

| 3H1H | G.G. | - | - | Q10 | 3.16 | 0.291 | 10 / 11 | 486 | p212121 | Berry [18] |

Orga - organisms: B.T. , B. taurus; G.G., G. gallus; M.L., M. laminosus; NOS, Nostoc sp. PCC7120; T.H., T. thermophilus; C.R., C. reinhardtii; P.D.; P. denitrificans; R.S., R. sphaeroides; R.C., R. capsulatus; S.C., S. cerevisiae

QP and QN site occupants: Azo, azoxystrobin; Trifloxy, trifloxystrobin; Myx myxothiazol; MOAS, MOA Stilbene; Kres, iodo-Kresoxim-dimethyl; Triaz, triazolone; Fam, famoxadone; Fen, fenamidone; Asc, ascochlorin; Croc, iodo-Crocacin-D; Stg, stigmatellin; Q2, ubiquinone Q2;Q10, ubuquinone Q10; Q6, ubiquinone Q6; Ant, antimycin.

Reso: resolution or diffraction limit of the crystal in units of Å: 1Å = 10−10 m.

Quality index; predictive power of model. A lower value of R (free) is better

MW: Molecular weight of dimeric bc1 complexes.

TBP, to be published.

in complex with cyt c.

2.2. Structure determination - current status

Crystallographic studies of cyt bc1 complexes have been approached in many different ways. There are currently 47 deposited experimental structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, Table 1). The first crystal structure obtained was for the ISP extrinsic domain (ISP-ED) fragment isolated by enzymatic treatment of bovine bc1 [15, 16]. Remarkably, it was the bovine heart mitochondrial bc1 containing no less than 11 different subunits and having a molecular weight of 490 kDa per dimer whose crystal structure was the first to be determined [12, 17, 18]. Structures of bc1 complexes from yeast and non-oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus were later obtained (PDB IDs: 1EZV, 2QJP, and 1ZRT) [19-21]. More recently, the bc1 structure from the soil bacterium P. denitrificans has also become available [22]. The high sequence similarity of bacterial bc1 complexes to their mitochondrial counterparts makes them excellent model systems for mitochondrial enzymes. It should be mentioned that structures of related b6f complexes from chloroplasts are also available [23], but an in-depth discussion of these works is outside the scope of this review. Because of the structural and functional complexities of the enzyme, all the structures determined by various research groups have provided information that revealed conformational intricacies of the complex and thus are not simply duplications of effort.

Structure determination of bc1 in complex with various respiratory inhibitors has been particularly successful with mitochondrial bc1 (Table 1), providing valuable insight into not only the mechanism of bc1 function but also the mechanisms of inhibition by these inhibitors. Inhibitors such as stigmatellin play a critical role in stabilizing bc1 in certain conformations suitable for crystal formation. For example, yeast bc1 was crystallized in the presence of stigmatellin or HHDBT [19, 24]; bc1 from R. sphaeroides can only be crystallized bound to certain types of inhibitors such as stigmatellin and famoxadone [25]. The functional significance of this conformational stabilization induced by inhibitor binding will be discussed later.

Cyt bc1 complexes isolated from different organisms and with different protocols have been crystallized utilizing various procedures and have yielded different crystal forms. Purification and crystallization procedures can influence the subunit compositions of isolated complexes in solution or in crystalline state. While all eleven subunits of the bovine bc1 have been observed [12, 17, 26, 27], the structures for yeast [19], chicken [18], and R. sphaeroides [21] each have one missing subunit. The structure of the mitochondrial bc1 of S. cerevisiae was determined with a monoclonal Fv fragment bound to the ISP subunit, providing critical contacts for crystal formation [19].

2.3. Overall structure and subunit organization of bc1

The crystal structures of mitochondrial bc1 confirmed the results from electron crystallographic studies [28, 29] that the functional form of bc1 is a dimer, as seen in all structures determined to date, and revealed the cross-talk of ISP subunits between symmetry-related monomers. They also confirmed the biochemically determined subunit composition [30] by showing that all eleven different subunits in bovine bc1 are present in crystals. Structures of the bc1 complex can be divided into three regions: the membrane spanning, the inter-membrane space (periplasm in bacteria or positive side of the membrane), and the matrix (cytoplasm in bacteria or negative side of the membrane) regions (Fig. 1A). There are 13 transmembrane (TM) helices in a monomer of bovine mitochondrial bc1; eight are contributed by the cyt b subunit and one each comes from cyt c1, the ISP, subunits 7, 10, and 11. For bacterial bc1 (Fig. 1B), the total number of TM helices is reduced to 10 or 11 for a monomer, depending on the presence or absence of the only supernumerary subunit. In mitochondrial bc1, supernumerary subunits 1, 2, 6 and 9 are exclusively present in the matrix region. Notice, however, that the subunit 9 is absent in yeast bc1 and none of these subunits are present in bacterial bc1. Subunit 8 is associated with cyt c1 at the intermembrane space side of the membrane for mitochondrial bc1. Again, this subunit is absent in the bc1 of bacteria.

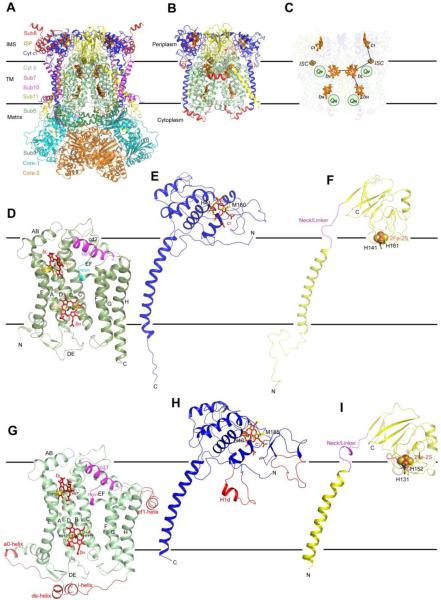

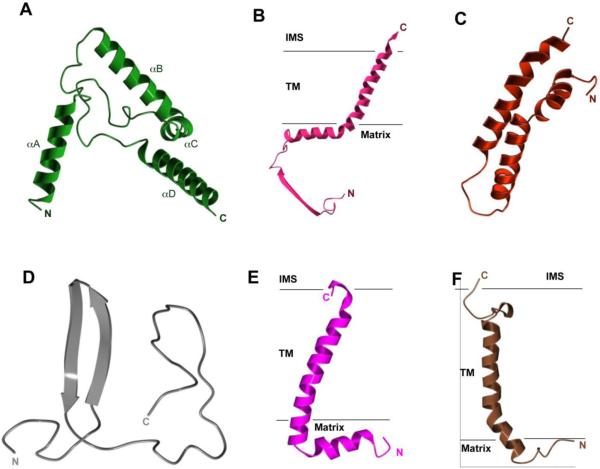

Figure 1. Crystal structures in ribbon representation for mitochondrial and bacterial bc1 complexes.

(A) Structural model of the dimeric bc1 complex from bovine mitochondria. The eleven different subunits are represented as ribbons with the color codes and subunit designations given on the left. Prosthetic groups such as the hemes bL, bH, and c1 are shown as stick models. The Iron-sulfur clusters are shown as van der Waals sphere models. The two black horizontal lines delineate the boundaries of the membrane bilayer. The three regions of the bc1 complex are indicated as IMS (intermembrane space), TM (transmembrane) and Matrix regions, respectively. (B) Structural model of the photosynthetic bacterium R. sphaeroides bc1. Color codes for Rsbc1 are the same as those for Btbc1 except those in red, which represent insertions in cyt b, cyt c1 and ISP subunits in relation to the corresponding subunits in Btbc1. (C) Positions of and distances between iron atoms of prosthetic groups. Hemes bL, bH and c1 as well as 2Fe-2S clusters are labeled. Arrowed lines indicate low and high potential chains for ET. (D) Ribbon diagram showing the structure of monomeric bovine cyt b. Eight TM helices are labeled. The two b-type hemes bL and bH are shown as stick models. The axial histidine ligands to the heme groups are also shown as stick models and labeled. The two conserved and functionally important motifs, the cd1 helix and the PEWY sequence, are shown in magenta and cyan, respectively, and as labeled. (E) Ribbon presentation of the structure of bovine cyt c1. Btcyt c1 has its N- and C-terminus on the positive and negative sides of the membrane, respectively. The heme c1 along with its two axial ligands BtM160 and BtH41 are shown as stick models. (F) Ribbon diagram showing the structure of the bovine ISP subunit. The N-terminus of the ISP is on the negative side of the membrane, whereas the C-terminus is on the positive side. The 2Fe-2S cluster is shown as spheres; the two histidine ligands H141 and H161 for the ISC are shown as stick models and are labeled. The flexible linker or neck between the TM helix and the ISP-ED is shown as a loop in magenta. (G) Ribbon diagram of the structure of Rscyt b. Structural features of the subunit are similarly labeled as those in Btcyt b except for the insertions, which are shown in red. Histidine ligands to the hemes bL (H97 and H198) and to bH (H111 and H212) are shown as stick models. (H) Ribbon representation of the structure of Rscyt c1. Structural features of the subunit are similarly labeled as those in Btcyt c1 except for the insertions, which are shown in red. Heme c1 ligands are given as stick models for M185 and H40. (I) Ribbon diagram showing the structure of RsISP. Structural features of the subunit are similarly labeled as those in BtISP except for the insertions, which are shown in red. Histidine ligands to the RsISC are show as stick models for H131 and H152.

From the first crystal structure of Btbc1 [12], the positions of the iron atoms in prosthetic groups and distances between them were initially obtained by anomalous difference Fourier maps (Fig. 1C) and ET rates between pairs of prosthetic groups, serving as weakly coupled donors and receptors, can be estimated based on the empirical approximation for intraprotein ET transfer (Table 2) [31]. The permissible ET routes thus obtained were mostly consistent with proposed high and low potential chains. Surprisingly, the shortest distance between the iron-sulfur cluster (ISC) and the edge of c1 heme is 27.7 Å, which corresponds to an estimated ET rate of 2.1 × 10−5 s−1. This ET rate does not permit the normal function of bc1. This conundrum was soon resolved, as it was discovered that the distance between the ISC and cyt c1 is not a fixed parameter. Several refined crystal structures of bovine as well as chicken bc1 revealed markedly different positions of the ISP-ED (Table 3), whereas the positions for b and c1 hemes remained unchanged [17, 18].

Table 2. Edge-to-edge distances (Å, upper triangle) and calculated ET rates (s−1, lower triangle) between pairs of prosthetic groups in dimeric bc1 of space group I4122 with the ISP in b-position.

| bH(1) | bL(1) | c1(1) | ISP(1) | bH (2) | bL(2) | c1(2) | ISP(2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bH(1) | - | 7.9 | 41.9 | 29.1 | 26.9 | 21.2 | 56.5 | 48.1 |

| bL(1) | 1.1×108 | - | 27.5 | 22.4 | 21.2 | 8.9 | 40.4 | 34.2 |

| c1(1) | 2.0×10−13 | 5.3×10−4 | - | 27.7 | 56.5 | 40.4 | 49.5 | 54.7 |

| ISP(1) | 1.6×10−5 | 0.85 | 2.1×10−5 | - | 48.1 | 34.2 | 54.7 | 59.8 |

| bH(2) | 4.9×10−5 | 0.83 | 2.4×10−22 | 4.2×10−17 | - | 7.9 | 41.9 | 29.1 |

| bL(2) | 0.83 | 4.7×106 | 7.2×10−12 | 5.4×10−8 | 1.1×108 | - | 27.5 | 22.4 |

| C1(2) | 2.4×10−22 | 7.2×10−12 | 8.0×10−19 | 7.2×10−22 | 2.0×10−13 | 5.3×10−4 | - | 27.7 |

| ISP(2) | 4.2×10−17 | 5.4×10−8 | 7.2×10−22 | 4.2×10−25 | 1.6×10−5 | 0.85 | 2.1×10−5 | - |

The calculated ET rates (ket, s−1), using the empirical expression logket = 15.2 − 0.61R − 3.1 (ΔG-λ)2/λ for weakly coupled donor-acceptor pairs [31], are based on edge-to-edge distances of R in Å, a driving force (ΔG°) under standard conditions of −0.13 eV for the donor-acceptor pairs of bL-bH and bH-c1, of −0.15 eV for the bH-ISP pair, of 0 eV for the pairs of bH-bH, bL-bL, c1-c1, and ISP-ISP, of −0.26 eV for the bL-c1 pair, and −0.28 eV for the bL-ISP pair, and a reorganization energy (λ) of 1.0 eV recommended for protein media.

Table 3. Conformational switch of the ISP-ED for the iron atoms of the ISC in different crystal forms and with different bound inhibitors.

| Space group |

Organism | Ligand at QP site | ISP position |

Normalized ISC ano peaka |

ISC-heme c1 distance (Å) |

Estimated ET rate (s−1) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14122 | B. t. | None | m c | 0.45 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [32] |

| I4122 | B. t. | Azoxystrobin | m c | 0.36 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [57] |

| I4122 | B. t. | MOAS | m c | 0.23 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [57] |

| I4122 | B. t. | Famoxadone | b d | 1.02 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [57] |

| I4122 | B. t. | Stigmatellin | b d | 1.20 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [57] |

| I4122 | B. t. | UHDBT | b d | 0.96 | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Xia [57] |

| P65 | B. t. | None | I1e | - | 23.6 | 0.007 | Iwata [17] |

| P6522 | B. t. | None | c 1 f | - | 7.8b | 2.9×107 | Iwata [17] |

| P212121 | B. t. | Kresoxim-dimethyl | I2 | - | 14.9b | 1361 | BerryTBP |

| P212121 | B. t. | Stigmatellin | b | - | 27.7 | 2.1×10−5 | Berry [112] |

| C2 | S. c. | Stigmatellin | b | - | 26.8 | 7.5×10−5 | Hunte [19] |

| P212121 | B. t. | Azoxystrobin | I2f | - | 14.6b | 2074 | BerryTBP |

| C2 | R. s. | Stigmatellin | b | - | 27.0 | 5.7×10−5 | Xia [21] |

| P21 | R. s. | Stigmatellin | b | - | 27.0 | 5.7×10−5 | Xia [21] |

Normalized anomalous difference Fourier peaks for the Fe atoms in the ISP subunits [58]

Distances are measured from ND2 of H161 of ISP to closest atom on the ring of heme c1

ISC at b-position is of low occupancy

ISC at b-position is of high occupancy

ISC at intermediate-1 position

ISC at c1-position

ISC at intermediate-2 position

TBP. To be published

2.4. Structures of the bc1 subunits essential for ET function

Three subunits are essential for the ET function of bc1: cyt b, cyt c1 and ISP. In eukaryotes, cyt b is the only subunit encoded and synthesized by mitochondria; it is entirely embedded in the membrane and consists of two helical bundles: helices A-E form the first and helices F-H belong to the second. The two b-type hemes are intercalated into the first bundle between the TM helices B and D. As was correctly determined by genetic studies, the heme bL was coordinated by the two histidine residues H83 and H182 (Bt cyt b) and the heme bH was liganded also by two histidine residues H97 and H196. The two b-type hemes are part of the active sites that catalyze opposite reactions: the QP (QO near bL heme) site, located near the inter-membrane space (IMS) in mitochondria or on the periplasmic side in bacteria, provides access to lipid-soluble QH2 for oxidation, and the QN (QI near bH heme) site, situated closer to the matrix (mitochondria) or cytoplasm (bacteria), carries out the reduction of ubiquinone. The two bundles contact each other on the negative side of the membrane, but separate on the positive side, creating a gap that is bridged by the cd helices (cd1 and cd2) and by the EF loop. A hydrophobic pocket below the cd helices and next to the ef helix is the ubiquinol oxidation site or QP pocket (Fig. 1D), which was first visualized by the binding of the QP specific inhibitor myxothiazol [12]. The location of the ubiquinone reduction site or the QN site was inferred from the antimycin-binding pocket of cyt b [12]. There are four prominent surface loops; three are on the positive side (AB, CD, and EF) and one is on the negative side (DE) (Fig. 1D).

Both the cyt c1 and ISP subunits are anchored to the membrane by TM helices with their respective extramembrane domains localized on the positive side of the membrane (Fig. 1E and 1F). Whereas the TM helix of ISP is N-terminal to its extrinsic domain, the one for cyt c1 is C-terminal. The extrinsic domain of the ISP subunit (ISP-ED) was found to be largely disordered in native and completely disordered in myxothiazol-bound bc1 crystals of space group I4122 [12, 32], but was found ordered in different positions in crystals of space groups P212121, P21, P6522, and P65 [17, 18] (Table 3).

When sequences of Mtbc1 and Rsbc1 are compared, the latter often possess more insertions than deletions [21, 33]. Remarkably, the insertions occur only on or near the periplasmic or cytoplasmic side and not within the transmembrane region (Fig. 1B). An understanding of the functions of these additions or deletions may provide insight into the evolutionary process that transformed the bacterial enzyme into its mitochondrial equivalent. When compared to the bovine cyt b, the structure of bacterial cyt b is essentially identical. Rs cyt b features two terminal extensions and two major insertions. The N- and C-terminal extensions are 22 and 29 residues long, respectively; They each contains extramembrane helix named a0 and i, respectively (Fig. 1G). One insertion (de helix) is in the cytoplasmic DE loop and another (ef1 helix) is found after the ef helix on the periplasmic side. Thus, except for the ef1 helix, all extensions and insertions are located on the N-side of the membrane and they likely function to maintain the structural integrity of the quinone reduction site by preventing potential electron leakages and by safeguarding channels for proton influx. On the periplasmic side, there is one large insertion of 18 residues (310-327) between Pro285 and Asn286 (Bt cyt b) containing the ef1-helix, which protrudes from cyt b laterally and runs parallel to the membrane surface. This insertion occurs only in species that belong to the phylum proteobacteria. However, it is functionally important, as the point mutation S322A (Rs cyt b) or deletion of residues 309-326 (Rs cyt b) significantly lowers the enzyme activity [34]. The ef1-helix may play an important role in lipid binding, as features of several potential lipid molecules are visible in the electron density. It also enhances crystal contacts through aromatic stacking interaction between a pair of Trp313 residues from adjacent cyt b subunits [21].

Structure-based sequence alignment revealed that cyt c1 of Rsbc1 has undergone both insertions and deletions relative to mitochondrial complexes [21]. Apart from the two small insertions in the Rs cyt c1 after Glu52 (4 residues) and Ala146 (3 residues), there is one large insertion between Gly109 and Gly127 (Rs cyt c1). It features a short helix (H1d) that protrudes from cyt c1 into the lipid bilayer sealing off a compartment between cyt c1 and cyt b (Fig. 1H). The only insertion in cyt c1 that may replace the function of a supernumerary subunit is the 18-residue insertion starting at position 162 (Rs cyt c1), which is spatially close to the head domain of ISP. This region is characterized by an increased disorder (high B-factor) but features a stabilizing disulfide bridge (Rs cyt c1, Cys145-Cys169), whose existence is in agreement with recently published data [35, 36]. Approximately 8 Å from the ISP-ED (Cα distance from cyt c1 Asn173 to ISP Asp143), this insertion presumably functions as an extended arm to limit its motion. Compared to mitochondrial cyt c1, two large deletions, near residues Thr77 and Ser92 (Rs cyt c1), respectively, result in the loss of bridging interactions between the two cyt c1 subunits within the dimer.

Structure-based sequence alignment shows one insertion in the sequence of Rs ISP. This insertion (residues 97-108) is 20-25 Å from the 2Fe-2S cluster and contributes to the surface of ISP-ED that faces away from cyt c1; it forms a globular structure containing three β-turns and one inverse γ-turn (Fig. 1I). There is an intricate network of interactions employing both main chain and side chain atoms, suggesting a stabilizing role for this insertion. Disruption of this network of interactions by more than one point mutation led to the loss of the ISP subunit in the complex [37].

3. Mechanism of ET-coupled proton pumping from a structural perspective

3.1. Q-cycle and bifurcation of electron flow at the QP site

Unlike other ET complexes of the respiratory chain, the bc1 complex uses ubiquinol to shuttle protons across the membrane and does so via the Q-cycle mechanism [38, 39] that obligates the bc1 complex to have a quinol oxidation site, a quinone reduction site and a bifurcated ET at the quinol oxidation site (Fig. 2). The critical experiments that led to the Q-cycle hypothesis included oxidant-induced cyt b reduction in the presence of the bc1 inhibitor antimycin [40, 41], identification of ISP as an oxidation factor [42], and the reaction stoichiometry of two protons translocated across the membrane for every electron transferred [43]. The identification of two postulated separate quinone reduction and quinol oxidation sites in the crystal structure further validated the “Q-cycle” mechanism [12].

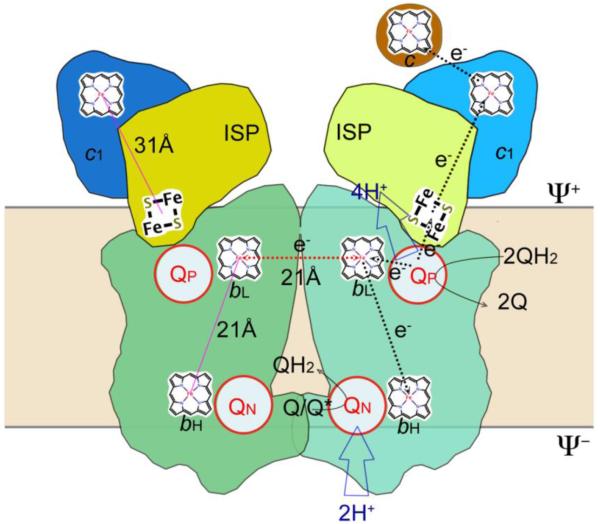

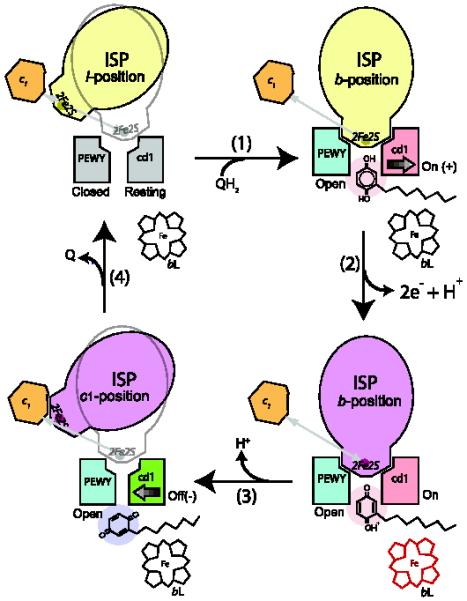

Figure 2. Q-cycle mechanism.

The Q cycle mechanism defines two reaction sites: quinol oxidation (Center P or QP) and quinone reduction (Center N or QN). It takes two quinol oxidation cycles to complete. At first, a QH2 moves into the QP site and undergoes oxidation with one electron going to cyt c via the ISP and cyt c1 (high-potential chain), and another ending in the QN via hemes bL and bH (low-potential chain) to form a ubisemiquinone, and releasing its two protons to the Φ+ site of the membrane. The second QH2 is oxidized in the same way at the QP site but its low potential chain electron ends up reducing the ubisemiquinone radical. Reduced QH2 is released upon picking up two protons from the negative side of the membrane. As a result of the Q cycle, 4 protons are transferred to the Φ+ side, 2 protons are picked up from the Φ− side and effectively only one QH2 molecule is oxidized.

The key step in the Q-cycle mechanism is the separation of the two electrons of the substrate QH2 at the QP site. The first electron of quinol is transferred to the “high-potential chain”, consisting of the ISP, cyt c1 and cyt c. The second electron is concomitantly passed through the “low-potential chain” consisting of hemes bL and bH, to reduce ubiquinone or ubisemiquinone bound at the QN site. This mechanism ensures a proton pumping efficiency of two protons per electron transferred to cyt c.

Although the Q-cycle hypothesis has received much experimental support, it does not explain why the two electrons do not both follow the high potential chain, which is thermodynamically more favorable [44]. In fact, the chemistry underlying the electron bifurcation at the QP site has been hotly debated, resulting in many proposed mechanisms, including the catalytic switch model [45], the double-occupancy Qo site model [46], the proton-gated charge-transfer mechanism [47], the logic-gated fit mechanism [48], a sequential model [49, 50], a concerted model [51-53], more recently, the R-complex model [54], the double-gated model [55], and the proton-transfer gating mechanism [56]. A mechanism named “Surface-affinity modulated ISP motion switch hypothesis” was proposed on the basis of the observed conformational switch of the ISP in the analysis of crystallographic data in the presence of various bc1 specific inhibitors [57, 58]. This and similar models [59] provides a simple explanation for the bifurcated ET at the QP site and its experimental basis will be outlined in the following sections.

3.2. Observed conformational change in the extrinsic domain of the ISP subunit in various crystal forms and in the presence of respiratory inhibitors

In the first Btbc1 structure reported, the ISP-ED is at the b-position [12]. As shown in Table 2, the shortest edge-to-edge distance between the ISC and heme c1 is 27.7 Å; ET along the high potential chain is not permissible under such conditions. Subsequent structure determinations showed ISP-ED in a number of different positions: near cyt c1 (c1-position) or at least two intermediate locations (I1- or I2-positions) (Table 3). When the ISP is at the c1-position (Bt P6522), the shortest edge-to-edge distance of cyt c1 heme to atom ND2 of BtH161 of the ISP, which is a ligand to the ISC, is measured at 7.8 Å, corresponding to an estimated ET rate of 2.9 × 107 s−1. The two intermediate distances found in deposited PDB coordinates are I1-position of 23.6 Å (Bt P65) and I2-position of 14.9 Å (Gg P212121). These distances would give ET rates of 0.007 s−1 and 1361 s−1, respectively.

Crystallographic studies in the presence of various inhibitors have been conducted for Btbc1, resulting in the observation of various conformations of the ISP-ED. Crystallographic studies of binding of QP site inhibitors to bovine bc1 led to the classification of two types of inhibitors: Pf and Pm inhibitors [58]. The Pf inhibitors immobilize or fix the conformation of the ISP-ED at the b-position and include the classic inhibitors stigmatellin, n-undecyl hydroxy dibenzothiazole (UHDBT), HDBT and n-nonyl quinoline N-oxide (NQNO), modern pesticides like famoxadone, 3-anilino-5-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-5-methyl-oxazolidine-2,4-dione (JG144), fenamidone and the natural inhibitor ascochlorin as well as iodo-crocacin-D (a compound optimized from natural crocacin D). Pm inhibitors release the ISP-ED from the b-position. This class of inhibitors contains the well-known natural inhibitor myxothiazol and also the synthetic compounds methoxy-acrylate stilbene and the widely used pesticides azoxystrobin, kresoxim methyl, trifloxystrobin, and triazolone.

Recently, structures of Ggbc1 (chicken bc1) in complex with either Pf or Pm inhibitors have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank (Table 1). In all Pf inhibitor complexes, the ISP-ED is found in the b-position, whereas in all Pm complexes, the ISP-ED is located in the I2-position. These structures are in complete agreement with what has been observed in inhibitor binding studies of Btbc1 [12, 26, 32, 57, 58].

3.3. Domain movement is necessary but not sufficient for bifurcated electron flow

The crystallographically observed inherent mobility of the ISP-ED, as the ISP-ED was not well ordered in the first bc1 structure [12] and the variable distances between the ISC and cyt c1 heme in subsequent structures [17, 18] led to the proposal of ET by domain movement to bridge the 27.7 Å gap [17, 18]. Experimental attempts to immobilize the ISP-ED by mutations or by cross-linking in bacterial and yeast bc1 complexes have invariably inactivated the enzyme [60-67], indicating that the mobility of the ISP-ED is necessary for the bifurcated ET of bc1. However, whether the observed mobility of the ISP-ED is sufficient to guarantee an obligatory electron bifurcation is questionable. First, the observed rate (80,000 s−1) of ET from the ISP to cyt c1 in Rsbc1 [68] is much faster than the turnover rate of the bc1 complex (~900 s−1), meaning that both electrons can potentially follow the high-potential chain. Second, the observed ET rate between the ISP and cyt c1 is independent of pH and the redox potential of the ISP, indicating that the rate is not limited by the electron transfer event according to the Marcus theory. Instead, a gating or control mechanism for ISP-ED movement must be in place [69]. Third, addition of purified ISP-ED to a preparation of bc1 without the ISP-ED only partially restores bc1 activity [70]. Fourth, free motion of ISP cannot explain the total inhibition of bc1 by antimycin, which acts remotely at the QN site. Thus, the mobility of ISP-ED itself is not sufficient to support a bifurcated ET at the QP site.

3.4. Capture and release of the ISP-ED is an inherent property of the cyt b subunit

The ISP subunits assemble into the bc1 dimer with their respective N-terminal TM helices anchored in one monomer while their C-terminal ISP-EDs reach over to interact with the other monomer (Fig. 1A and 1B). A linker region (residues 62-74 in the Bt ISP), whose flexibility is essential for the electron-shuttling function of the ISP, provides the connection between the TM helix and the ISP-ED (Fig. 1F and 1I). The ISP-ED binds to the ISP-docking surface on the cyt b subunit through the small tip area that surrounds the 2Fe-2S cluster and thus forms a part of the QP site. The tip of the ISP features a smooth, rigid, and largely hydrophobic surface suited to fit into a well-defined docking site.

Certain Pf inhibitors (stigmatellin and UHDBT) not only immobilize the ISP-ED but also increase its midpoint potential (Em7). Both observations were explained by the formation of a direct H-bond between an oxygen atom of the inhibitor and the presumably protonated BtH161 - a ligand of the 2Fe-2S cluster. In particular, the formation of this H-bond had been deemed essential for the fixation of the ISP-ED at the b-position. Structural studies of a number of additional inhibitor-bc1 complexes have appeared to support this notion [24, 54, 71]. However, this hypothesis is not compatible with the proposed QP site chemistry for ubiquinol oxidation, which involves the formation of a hydrogen bond between the substrate ubiquinol and the ISP, because ubiquinol cannot act as an inhibitor. Surprisingly, the bc1-famoxadone and bc1-JG144 complexes showed the ISP-ED in the fixed state as observed in the stigmatellin complex, yet there was no direct ISP-inhibitor interaction (Fig. 3A and 3B). It is therefore clear that direct H-bonding between the ISP-ED and the bound inhibitor may contribute to, but does not cause the conformational fixation of the ISP. Instead, the conformational switch of the ISP is an intrinsic property of the bc1 complex.

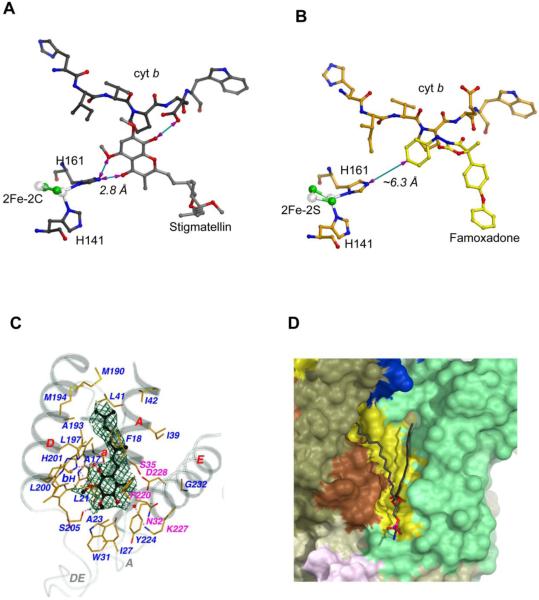

Figure 3. Binding of substrate, inhibitor and lipid molecules to the cyt bc1 complex.

(A) Hydrogen bonding interaction between stigmatellin and the ISP. In this figure, much of the protein structures of cyt b and ISP are omitted for clarity to illustrate the H-bond between stigmatellin and the ISC. All residues, the ISC, and stigmatellin are shown as ball-and-stick models and as labeled. The distance between BTH161, one of the 2Fe-2S ligand, and stigmatellin is shown as 2.8 Å. (B) No hydrogen bonding is observed between famoxadone and the ISP. Binding of famoxadone arrests the ISP-ED motion. But the closest distance between BTH161 and the ISP is >6 Å. (C) Interaction of the protein environment at the QN site of the cyt b subunit with bound substrate ubiquinone with two isoprenoid repeats. Secondary structure elements surrounding the QN pocket, including portions of the N-terminal helix a, TM helices A, D, and E, and extra-membrane loops A and DE, are shown and are labeled. Residues interacting with bound substrate and the bH heme are drawn in stick models and are labeled with carbon atoms in yellow, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, and iron in orange. H-bonds are indicated with pinkish dotted lines. Water molecules are shown as isolated red balls. The residues that are with magenta labels confer inhibitor resistance. The substrate ubiquinone, caged in Fo-Fc electron densities calculated with refined phases after ligand being omitted and contoured at the 3σ level in dark green, are drawn as ball-and-stick models with carbon atoms in black, nitrogen in light blue, and oxygen in red. Additionally, the two bound water molecules are enclosed in the Fo-Fc electron density in cyan calculated with refined phases obtained with the waters omitted and contoured at 3σ. (D) Binding environment of the bound lauryl oleoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) in the structure of Rsbc1. The modeled lipid is located near the N-side and its binding environment is shown.

If the conformational switch or capture-and-release of the ISP-ED is indeed an intrinsic property of bc1, an important question is whether the ISP-ED can undergo the fixed to mobile conformational transition in the absence of inhibitor binding, as this is highly relevant to bc1 function under physiological conditions. Preliminary results from redox-coupled crystallographic studies of Btbc1 [72, 73] showed ISP-ED is in the fixed position when the complex is fully reduced, whereas it is mobile when oxidized. Thus, conformation transition of the ISP-ED can also be achieved with electronic signals, most likely from ET in the cyt b subunit.

3.5. Mechanism of ISP-ED’s capture and release

The ISP binding surface of cyt b has the appearance of a volcanic crater; most residues that contribute to the crater are hydrophobic in nature and only 16 of them have side chains facing the ISP. Of these residues, all but one are located on the CD and EF loops, which connect helices C and D, and helices E and F, respectively (Fig. 1D and 1G). Two structural motifs within the CD and EF loops, the conserved cd1 helix and the PEWY sequence motif, undergo large movements upon binding of QP site inhibitors. Inhibitor binding generally causes the PEWY motif, as measured for residue BtP271 of bovine cyt b, to back away in a unidirectional fashion from the QP pocket by more than 1.5 Å, whereas the direction in which the cd1 helix moves clearly correlates with the type of bound inhibitors when compared to the structure of inhibitor-free bc1. Invariably, the inhibitors that are known to promote the mobile state of the ISP-ED cause a negative shift, whereas all inhibitors that cause the capture of the ISP at the QP site lead to a positive displacement of the cd1 helix; here the positive or negative denotes the direction of the shift relative to the inhibitor-free enzyme. More precisely, the positional shifts of the cd1 helix are roughly parallel to the membrane surface; the positive shift signifies a displacement of the cd1 helix swinging outward away from the QP pocket leading to an expanded QP pocket, and the negative shift indicates an inward displacement. The importance of the cd1 helix in bc1 function is also manifest in its high degree of sequence conservation, which reaches 98.5% identity (averaged over 14 residues), based on an analysis of a 5,355 non-redundant cyt b sequence set, as compared to the cd2 helix (73.5% for 9 residues) or to the whole subunit (75.2% for 379 residues), a fact that has been known for a long time but had no clear explanation [74].

The mechanism that induces this dramatic transition in ISP-ED conformation and how the signal is transmitted from the source (the binding of inhibitor to the QP site) to the target residue(s) that capture the ISP-ED have been investigated [57]. Two possible interaction forces at the ISP-ED binding surface were looked at separately without assuming that they were mutually exclusive: (1) changes in hydrogen bonding patterns and (2) adjustments in van der Waals (vdw) interactions expressed as changes of surface complementarity. It is conceivable that, if the bifurcation of ET requires a control mechanism for ISP-ED conformational switch, the formation of a large number of strong H-bonds between the docked ISP-ED and the docking site would be unfavorable for the switch for energetic reasons. Indeed, in the structures where the ISP-ED is in the fixed conformation or b-position as seen in the complexes of Pf inhibitor famoxadone, stigmatellin, JG144, NQNO, UHDBT, ascochlorin or crocacin as few as seven H-bonds are formed between the ISP and cyt b. While two of them are permanent and found in the neck region of the ISP of all structures, the remaining five H-bonds are made with the ISP-ED as long as the ISP remains docked. Most notably, only carbonyl oxygen atoms of the backbone are employed by the ISP for non-permanent H-bonds. The non-permanent H-bonds disappear when Pm inhibitors like azoxystrobin, MOA-stilbene or myxothiazol are bound. Extensive mutagenesis studies in the cyt b subunit including the RsK287-S151 dyad and ScY278 (RcY302) [7, 57] appear to rule out that the change in H-bonding pattern controls ISP capture and release.

When the van der Waals interactions were examined (expressed in terms of changes in contact area (CA) and in surface complementarity (SC) of the two interacting surfaces between the cyt b and the ISP-ED), it was clear that changes in CA and SC are correlated to the movement of the cd1 helix. As one goes from Pf- to Pm-type inhibitors, there is a decrease in the CA and most notably a nearly 40% loss in SC. Since the ISP-ED has shown no sign of internal plasticity and the cd1 helix is known to undergo a shear motion as inhibitors bind to the QP site, the change in shape complementarity caused by the cd1 motion represents a possible mechanism that could account for the change in binding affinity of cyt b toward the ISP, thus regulating ISP conformational dynamics.

Although the cause and effect relationship is apparent for the binding of different types of inhibitors and the conformational switch of the ISP-ED, the same relationship cannot be said with absolute certainty for the movement of the cd1 helix and the ISP-ED switch. However, circumstantial evidence does exist. (1) Inhibitors such as famoxadone do not contact the ISP-ED directly. Thus capture of the ISP-ED by famoxadone binding likely follows the sequence of inhibitor binding to cyt b, followed by cd1 helix movement, changing the shape of the ISP-ED binding crater, and subsequent ISP-ED arrest. (2) ISP-ED conformational switch can be mediated by changes in redox conditions in the absence of inhibitors. Under such conditions, the reduction of cyt b likely signals the movement of the cd1 helix, leading to capture of the ISP-ED. (3) Even before the role of the cd1 helix was proposed, the activity of bc1 was found to be dependent on the size of the residue at position 155 of the cd1 helix (Rsbc1). The larger the size of the side chain, the less activity the bc1 complex has [75]. Examination of bc1 structure indicates that mutation of residue RsS155 to a larger residue would limit the movement of the cd1 helix, leading to inactivation.

3.6. Affinity controlled ISP conformational switch hypothesis for bifurcated ET at QP site

A control mechanism, called the “binding affinity modulated ISP-ED motion switch hypothesis” has been proposed, allowing modulation of the binding affinity toward the ISP-ED by the cyt b subunit [57, 76] (Fig. 4). The basic principle of the hypothesis is that the cyt b subunit controls the rate of electron flow in the high potential chain by controlling the ISP-ED conformation state and regulating the distance between the ISC and heme c1, thus ensuring the bifurcated flow of the two electrons from ubiquinol. The following sequence of events during the QH2 oxidation may take place: (1) In the absence of any substrate at the QP site, the ISP-ED is capable of sampling the QP site frequently. The binding surface on the side of cyt b is in a resting state in a sense that its shape matches that of the ISP-ED sufficiently well to keep it in proximity but not enough to hold it in a fixed conformation. This state is characterized by the ef helix in the “closed” position and the cd1 helix in the “resting” position. (2) When a substrate QH2 molecule enters the catalytic site (Fig. 4, step 1), it proceeds to the distal part of the QP pocket. To accommodate the QH2 molecule, the ISP-binding crater widens by moving the cd1 switch toward the “on” position and by pushing the ef helix to the “open” position. The reshaping of the ISP-binding site increases its affinity for the ISP-ED to the point of its fixation in situ. As a result, a transient cyt b-QH2-ISP complex forms, which features an H-bond from BtH161 of the ISP to the substrate. The distance from the ISC to heme c1 is now fixed at 27.7 Å. (3) As the first electron is being transferred to the ISP (Fig. 4, step 2), the one-electron carrier remains fixed in place, and the second electron in the Q radical has to enter the low-potential chain, a process that likely occurs simultaneously with the first ET and possibly via residue BtY131, which undergoes a large conformational change when bound with UHDBT [58]. The notion of a concerted ET is supported by the inability to detect an ubisemiquinone radical on the EPR time scale and by the observation of simultaneous reduction of the ISP and bL heme in pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of the ET at the QP site [52]. We speculate that as the second electron moves toward the bH heme (Fig. 4, step 3), the proton translocation is accomplished. It is worthwhile to emphasize that because the reduced ISP is fixed at the b-position, which is at a non-permissive distance from c1 heme for ET, the first electron remains in the ISP. This simple mechanism ensures the bifurcated ET of the two electrons. (4) The Q molecule exits via the proximal binding site in the QP pocket; this event would reverse the pressure on the cd1 helix, retract it to the “off” position, and cause the release of the ISP-ED. The ef helix stays at the open position until the product exits the QP pocket (Fig. 4, step 4).

Figure 4. Control of the ISP-ED motion switch and the proposed mechanism for bifurcation of electron flow at the QP pocket.

The structural components necessary for the control of the ISP conformational switch are illustrated in this cartoon rendition of the QP pocket. The PEWY motif and cd1 helix in gray represent a native (Resting) configuration. The ISPs in yellow and magenta are in oxidized and reduced forms, respectively. The heme bL is red when it is reduced. The PEWY motif in blue stands for the open configuration as in the state with a bound QP site inhibitor. The cd1 helix in red symbolizes the conformation (On) as in the presence of a Pf inhibitor occupying the distal site (pink), and the cd1 helix in green shows the conformation (Off) when a Pm inhibitor is occupying the proximal site (purple). Cyt c1 is shown in orange.

An important concept of this hypothesis is that the ISP-ED remains fixed at the QP site or b-position until the transfers of the second electron and protons from ubiquinol are completed, which effortlessly explains the high fidelity of the bifurcation of the electron pathway. This hypothesis is consistent not only with structural data but also with a great deal of biochemical, biophysical and genetic evidence: (1) it provides a functional explanation for the extraordinary sequence conservation of the cd1 helix. (2) A logical consequence of this hypothesis is that the reduction of b hemes precedes that of cyt c1, as shown by the pre-steady state kinetic analysis [52, 77-79]. (3) It agrees well with the observations that mutations introduced into the ISP-ED binding surface mostly affect the ET kinetics between the ISP and cyt c1 but rarely influence the substrate binding, as in RsK329A of R. sphaeroides [57], ScW142 of yeast [80], RsL286 and RsI292 of R. sphaeroides [81], RsK329 of R. sphaeroides [82], ScY279 of yeast (RcY302 in R. capsulatus) [6, 7] and RsT160 of R. sphaeroides [83]. (4) The hypothesis predicts that limiting the movement of the cd1 helix leads to modification in the activity of the complex depending on the size of substitution, as seen in RsS155 of R. sphaeroides [75] and in RcG158 of R. capsulatus [84]. (5) Since antimycin is known to act remotely at the QN site, it would be difficult to explain how antimycin could completely inhibit steady state bc1 activity, especially in the context of ISP head domain undergoing a free motion. The observed redox-dependency of ISP-ED conformational switch shows an immobilized ISP-ED when bc1 is fully reduced, which readily explains the strict inhibition of bc1 by antimycin.

Despite its simplicity as a control mechanism for bifurcation of electron flow at the QP site, this hypothesis does not adequately define the signaling pathway that triggers the capture and release of ISP-ED under physiological conditions. One possibility is that the ET from hemes bL to bH causes protein conformational changes in the cd1 helix and allows or forces the reduced ISP-ED to move from the b-position to the c1-position to be oxidized [85, 86]. Such a redox-induced conformational change in the cyt b subunit has yet to gain direct experimental support. A second possibility involves the binding of the substrate QH2 to and exit of the reaction product Q from the QP site, leading to capture and release of the ISP-ED [32].

4. Interaction with substrates, lipids, inhibitors and metal ions

4.1. Interaction with cytochrome c

Despite the presumed transient interaction between bc1 and cyt c, the crystal structures of bc1 in complex with either isoform-1 or -2 of cyt c of S. cerevisiae were obtained to 2.97 Å resolution for the oxidized cyt c and to 1.9 Å resolution for the reduced cyt c, respectively [87, 88]. It should be mentioned that in both cases the complex was crystallized in the presence of a bound Fv fragment derived from a monoclonal antibody and QP site inhibitor stigmatellin. As expected, the cyt c binds to the c1 subunit of bc1. Surprisingly, however, the binding is sub-stoichiometric with one cyt c bound to one c1 subunit, while the second site on the bc1 dimer remains unoccupied or possibly exhibits very low occupancy or severe disorder. The binding forces were characterized as mostly nonpolar in nature. The close spatial arrangement of the two cytochromes reduces the distance between the CBC atoms of the two respective heme vinyl groups to 4.5 Å and the distance between the two iron centers to 17.4 Å. Furthermore, the observed interplanar angle of the heme groups is 55°, suggesting a direct and rapid heme-to-heme electron transfer at a calculated rate of up to 8.3 × 106 s−1. In the structure, no direct interaction has been observed between subunit QCR6 and cyt c; the former is a small acidic protein thought to be involved in cyt c binding.

In the reduced state, the dimer structure is asymmetric, as the binding of monovalent cyt c is correlated with conformational changes in the ISP-ED and subunit QCR6 and with a higher number of interfacial water molecules bound to cyt c1. There exists a mobility mismatch at the interface, with disordered charged residues on the cyt c side and ordered ones on the cyt c1 side, which could be significant for transient interactions [88].

4.2. Interaction with ubiquinone at the QN site

Assignments of bound substrate ubiquinone (Q) have only been made to the QN site. Initial indication for bound Q came from the difference density map between antimycin–bound and native crystals [12], as a negative density appeared in a pocket in the TM region of cyt b next to the bH heme site, which represented part of a ubiquinone molecule that is bound in the native crystal but is displaced by bound antimycin A. This suggests that the antimycin binding site partly overlaps the quinone reduction site QN. In the yeast structure [19], a Q6 (ubiquinone with six isoprenoid repeats) was fitted into the electron density in the QN site. In bovine and R. sphaeroides bc1, a Q2 was identified [21, 27, 58].

As no ubiquinone was added, the natural substrate identified in the native bc1 crystal (1NTZ, Table 1) was obviously retained during purification and crystallization. In the refined bovine bc1 structure [27], a piece of electron density was located at the QN site of the cyt b subunit more than 5σ above the mean, into which a ubiquinone molecule with its first two isoprenoid repeats was fitted. The two possible orientations of the planar ubiquinone ring could not be distinguished from the shape of the electron density (Fig. 3C). The average B factor of the bound ubiquinone is twice as large as its immediate protein environment, suggesting most likely a lower than 50% occupancy in the crystal. The quinone ring is nearly perpendicular to the plane of the phenyl ring of BtF220 and to that of heme bH; the former forms an Ar-Ar pair with the ubiquinone (3.0 Å), and the latter has the closest distance of 4.2 Å. There are three H-bonds formed between the bound ubiquinone and the QN site residues BtD228, BtH201 and BtS205; some of these H-bonds are mediated by water molecules. The two isoprenoid repeats that were visible in the electron density are in contact with residues BtP18, BtS35, BtG38, BtM190, BtL197, and the bH heme. The van der Waals surface of the matrix side of these TM helices, particularly in cyt b, features channels leading to the QN site and serving as possible proton uptake pathways. Conformational changes in residues contacting bound quinone, as exhibited in crystal structures of yeast and bovine bc1, implicate possible mechanisms for proton uptake from the matrix into the QN pocket [27].

In the Rsbc1 structure the natural substrate Q bound to the crystalline bc1 is estimated to have 70% occupancy based on the comparison of average B factor of the Q to side chain atoms of surrounding, interacting residues [21]. The quinone molecules are roughly perpendicular to the parallel planes of RsF216 and heme bH on one side and parallel to the plane of RsF244 on the other side. When the six monomeric bc1 structures from a crystallographic asymmetric unit are aligned, the positions and orientations of bound Q are different; the largest positional and rotational displacements are 1.3 Å and 38°, respectively. Residue RsH217 (BtH201) forms H-bonds with Q molecules with the O2-NE2 distances in the range of 2.2–2.4 Å, indicating that the imidazole ring of RsH217 follows the motion of Q, consistent with its observed conformational flexibility.

4.3. Interaction with bound lipid and detergent molecules

Cyt bc1 is an integral part of the cellular membrane and consequently, lipid molecules play an essential role in its function [89, 90]. In eukaryotic cells, a characteristic phospholipid is cardiolipin, which primarily exists in mitochondria and was shown to be essential for the function of bc1 [14]. Crystal structures of bc1 from various species have revealed bound lipid molecules [21, 91]. The roles of these bound lipid molecules are proposed to be two fold: promoting structural integrity of the complex and stimulating enzyme activity. Structural assignment and functional analysis for five crystallographically resolved bound lipid molecules was described for yeast bc1 [91]: two phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), one phosphatidylcholine (PC), one phosphatidyinositol (PI), and one cardiolipin (CL) and one detergent molecule DDM. These molecules are bound to the TM region at the surface of the two monomers and in two large lipophilic clefts that are present at the dimer interface. Their head groups are bound to the protein surface in regions with positive electrostatic potential. The assignments were solely based on the appearance of electron density.

Two lipid molecules have been described in considerable detail in the yeast complex: a PI molecule was found to bind in an unusual interhelical position near the flexible linker region of the ISP and a CL is positioned at the entrance of a proposed proton uptake site. The mutagenesis analysis of the CL site showed that CL binding is critical for the respiratory super complex formation [92].

In crystals of Rsbc1, ordered lipid molecules are often found on the boundary surface between symmetry-related dimers, at the dimer or subunit interfaces, and in surface depressions [21]. One lipid molecule was positively identified on the N-side of the membrane and included in the model. However, additional lipids that are only partially recognizable at both sides of the membrane were excluded in final models. The lipid molecule bound at the cytoplasmic surface of cyt b is modeled as a lauryl oleoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE); its head group aligns with the surface plane of the cytoplasmic leaflet of the membrane and its fatty acid chains flank the TM helices B and G of cyt b (Fig. 3D). The exact identities of the fatty acids are unknown but the assignment as PE is supported by comparing it to the lipids present in bovine and yeast bc1. The phosphate group is hydrogen bonded to two highly conserved consecutive tyrosine residues (RsY117 and RsY118), and the lipid head group is further stabilized by the side chain of RsR358 by forming an ion pair with the lipid phosphate.

At the N-terminal end of the ef1 insertion in cyt b, which is unique to bc1 of bacteria, the side chain of RsW313 forms a stacked pair with its symmetry-mate from a neighboring dimer at a distance of 3.8 Å. This pair is symmetrically flanked by at least six pieces of extra electron density, most likely stemming from bound lipid or detergent molecules [21]. A strontium ion, clearly confirmed by its anomalous signal, sits right above the indole rings of the tryptophan pair. Its exact coordination environment cannot be resolved, but might involve the head groups of two pairs of putative lipid molecules. We observed the tryptophan pair formation in all crystal forms, and the presence of strontium ions seems to strengthen the interaction but is not required.

4.4. Interaction with QN and QP site inhibitors

As a central component of the cellular respiratory chain, the bc1 complex became an easy target for numerous natural antibiotics, as a result of constant battle for survival over the course of evolution. Examples of natural compounds that specifically target the bc1 complex are antimycin A, strobilurin, myxothiazol, and stigmatellin. Many of the earlier functional and mechanistic studies of the bc1 complex were facilitated by the use of these inhibitors, which block ET at selected points [93]. Structural analysis of bc1 complexes also benefited from these inhibitors, as they stabilize certain conformations at a given state. By manipulating differences in uptake between the host and pathogens, some of the inhibitors or their derivatives have been developed into anti-fungal and anti-parasitic agents and are used in agriculture to control fungal or bacterial diseases and in medicine to treat infections.

Historically, bc1 inhibitors were classified based on their effects on bL-heme spectrum and impact on the redox potential of the ISP, due to a lack of understanding of the underlying process [94]. On the basis of structural information, bc1 inhibitors are currently divided into QP site inhibitors (P), the QN site inhibitors (N) and the dual site inhibitors (PN) [58]. An increasing body of structural evidence starting with the first structures of bc1 [12] followed by a number of high resolution inhibitor bound bc1 complex structures suggested that the influence of the inhibitor on the mobility of the ISP-ED was systematic. Accordingly, all known QP site inhibitors can be divided into two subgroups [57, 58], namely those that fix the conformation of the ISP-ED in the b-position (Pf-type) and those that mobilize it (Pm-type). In the latter case, the ISP-ED may be found in the c1-position (PDB IDs: 3L70, 3L71, and 3L72) but could also be anywhere between the b and c1-position (PDB IDs: 1SQP and 1SQQ).

The class of known Pf inhibitors encompasses stigmatellin, UHDBT, HDBT, NQNO, famoxadone, JG144, fenamidone, ascochlorin and iodo-crocacin-D. The class of Pm inhibitors contains the well-known natural inhibitor myxothiazol but also the synthetic compounds methoxy-acrylate stilbene and the widely used pesticides azoxystrobin, kresoxim methyl, trifloxystrobin, and triazolone. This group contains derivatives of strobilurin, whose structure-activity relationship advanced the research in respiratory chain complex III inhibitors. Given the consistency of the mode of binding in this group, it could be expected that all methoxy-acrylates, methoxy-carbamates, oximino-acetates, oximino-acetamides and benzyl-carbamates would belong to this group. The class of N inhibitors is comprised of compounds that occupy the QN site. This group is still rather small and starts with the natural inhibitor antimycin but also contains NQNO and ascochlorin, for which crystal structures were determined (Table 1). No structural information is currently available that would illuminate how a number of natural inhibitors like funiculosin or the important pesticides cyano-imidazole (cyazofamid) and sulfamoyl-triazole (amisulbrom) might bind. The class of PN inhibitors is essentially not a new class, as members of this group are listed in both the P and N class (Table 1). Its presence only underlines the fact that some inhibitors have features (just as the quinol/quinone pair) that allow them to bind to both active sites. This group includes NQNO, ascochlorin and tridecyl-stigmatellin (observed in b6f) [95].

4.5. Interaction with metal ions

When incubated with mother liquor containing 200 μM ZnCl2 for seven days, the crystalline chicken bc1 complex specifically binds Zn2+ ions at two identical sites or one per monomer in the dimer [96]. Zinc binding occurs close to the QP site and is likely to be the reason for the inhibitory effect on the activity of bc1 observable during zinc titration [97, 98]. The Zn2+ ion binds to a hydrophilic area between cytochromes b and c1 (PDB: 3H1K) and is coordinated by GgH212 of cyt c1, GgH268, GgD253, and GgE255 of cyt b, and might interfere with the egress of protons from the QP site to the intermembrane aqueous medium. No Zn2+ was bound at the zinc binding motif of the putative MPP active site of core-1 and core-2 for chicken bc1 after prolonged soaking [96] nor was it found in the native bovine or yeast structures [12, 19].

Crystals of Rsbc1 grown in the presence of strontium ions revealed several Sr2+ binding sites. One site that is not present in mitochondrial bc1 but appears to be conserved in photosynthetic bacteria is on cyt c1 [21]. The strontium ion, confirmed by the appearance of a strong anomalous signal from the data set collected above the strontium absorption edge, is accessible from the periplasm and coordinated by side chains of RsD8, RsE14, and RsE129 as well as by the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of residue RsV9 in a distorted octahedron. At the N-terminal end of the ef1 insertion in cyt b, the side chain of RsW313 forms a stacked pair with its symmetry-mate from a neighboring dimer at a distance of 3.8 Å. A strontium ion, clearly confirmed by its anomalous signal, sits right above the indole rings of the tryptophan pair. In this case the role of strontium ions seems to reinforce the interaction of the tryptophan pair.

5. Structures of supernumerary subunits and their functional implications

Common to all bc1 complexes are the three subunits that contain redox prosthetic groups. In higher organisms, there are additional subunits with more than half of the total molecular mass of the complex, which are called supernumerary subunits. The role of these subunits has been a matter of debate. Since they are not required for the ET function of bc1, it was previously assumed that the additional subunits had structural rather than functional roles. The supernumerary subunits include two large extrinsic proteins named core-1 and core-2, and another four to six smaller subunits of molecular mass under 15 kDa. Most supernumerary subunits are not embedded in the membrane, but peripherally localized at the membrane surfaces, mostly at the matrix side of the membrane.

5.1. Structures of core-1 and core-2 subunits of mitochondrial bc1

The core proteins contribute to more than one-third of the total mass of the bc1 complex. The function of the core proteins in non-plant species is not understood fully. They are, however, required for full activity and stability of the bc1 complex [99]. In yeast, the core proteins were shown to be required for assembly of the complex [100]. In plants, the core proteins have a unique peptidase function [2, 101].

The core-1 and core-2 subunits of bovine bc1 are synthesized in the cytosol as precursor proteins of 480 and 453 amino acid residues, respectively, which are proteolytically processed as they are being transported into mitochondria by removing 34 and 14 residues, respectively, from the N-termini of core-1 and core-2 precursors. Core-1 and core-2 share 21% sequence identity and expectedly, their three-dimensional structures are remarkably similar (Fig. 5A and 5B). Each of the core subunits consists of two structural domains of about equal size and almost identical folding topology, which are also related by approximately two-fold rotation symmetry, even though only about 10% of the residues are chemically identical. Both domains are folded into one mixed β-sheet of five or six β-strands, flanked by three α-helices on one side and one α-helix from the other domain on the other side.

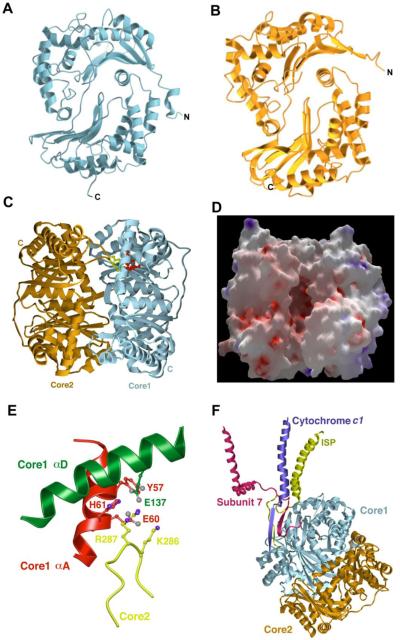

Figure 5. Structures of core proteins of bovine mitochondrial bc1 complex.

(A) Ribbon representation of the structure of the core-1 subunit showing two domains of the α-β structure related by an intradomain approximate twofold rotational axis perpendicular to the plane of the diagram (B) Structure of the core-2 in the form of a ribbon diagram showing in similar orientation as the core-1 subunit in (A). (C) Structure of core-1 (cyan) and core-2 (coral) heterodimer viewed parallel to the intersubunit approximate two-fold rotational axis. The two molecules are associated such that the N-terminal domain of core-1 is facing the C-terminal domain of core-2. The putative zinc-binding motif is shown as ball-and-stick models, which is detailed in (E). (D) Electrostatic potential surface representation of the core-1 and core-2 heterodimer. The surface is shown in the same orientation as in (C). Red surface represents negative potential and blue positive. (E) Structural arrangement of the zinc-binding motif in the core subunits of the bc1 complex. Residues from the two α helices, αA (green) and αD (red) that are separated by more than 50 residues, contribute to the zinc-binding motif. Residues important for Zn binding from these two helices come together in the 3-D structure and are joined by BtR287 and BtK286 from the core-2 subunit (yellow). (F) Attachment of core proteins to the bc1 complex. Core subunits are anchored to the TM region of the complex by recruiting and incorporating peptides from subunit 7 (red) and cyt c1 (blue) into a β-sheet in the core-1 subunit. The ISP subunit (yellow) provides additional interactions with the core-1 subunit.

The overall shape of each core protein resembles a bowl. In the assembled Btbc1 complex, the N-terminal domain of core-1 interacts with the C-terminal domain of core-2, and vice versa (Fig. 5C). Core-1 and core-2 enclose a large, acidic cavity that was also observed by electron microscopy [29] (Fig. 5D). Because the two internal approximate two-fold rotation axes of core-1 and core-2 differ in direction by 14.5°, the two bowls representing these proteins come together in the form of a ball with a crevice leading to the internal cavity (Fig. 5D). The crevice is filled with peptide fragments that were assigned as part of subunit 9, a signal peptide of the ISP subunit [12]. The amino acid residues lining the wall of the cavity are mostly hydrophilic.

Yeast COR1 and QCR2 have sequence homologies of 51% and 50% to the corresponding core-1 and core-2 subunits of bovine bc1, respectively [19]. The differences between the two species are most pronounced in the C-terminal domain of QCR2. The subunit is 68 residues shorter than the corresponding bovine core-2; its N-terminal domain has a five-stranded β sheet, whereas the bovine core-2 is six-stranded. In the bovine complex the cleaved signal peptide of the ISP (subunit 9) is located in the crevice between the core-1 and core-2 proteins [12], the binding of which is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with this β sheet. Polar or charged residues are present at the corresponding positions in yeast [19]. Thus, this cavity formed between COR1 and QCR2 is larger in yeast and open to the bulk solvent and no electron density was found for a retained signal peptide.

The core-1 and core-2 heterodimer of Mtbc1 is thought to be a relic of the broad family of metalloproteases. In particular, the core proteins of mammalian bc1 complexes are homologous to the subunits of the general mitochondrial matrix processing peptidase (MPP), which cleaves signal peptides of nucleus-encoded proteins after import into the mitochondrion. MPP belongs to a family of metalloendoproteases whose members include insulin-degrading enzymes from mammals and protease III from bacteria. Mammalian and fungal MPP are soluble heterodimers of α- and β-subunits localized in the mitochondrial matrix. Both subunits of MPP are required for the protease activity, but the active site is part of the β-subunit. The core-1 protein of the bovine bc1 complex has 56% sequence identity to the β-subunit of rat MPP, 38% to yeast, and 42% to potato, whereas the core-2 protein is 27% identical to the α-subunit of rat MPP, 28% to yeast, and 30% to potato. Interestingly, the sequence identity of the bovine core proteins to the related MPP subunits of yeast is significantly higher than that of the yeast subunits itself [19]. We can therefore expect that the MPPs of these species are similar in structure to the bovine core-1 and core-2 subunits. In plant mitochondria, the MPP activity is membrane-bound and is an integral part of the bc1 complex [2].

The bovine core-1 features a inversed putative Zn-binding motif consisting of two α helices (αA and αD, Fig. 5E) with a modified zinc-binding sequence of BTY57XXE60H61-(X)75-E137, compared to the consensus sequence of HXXEH-(X)74-76-E [102]. In yeast, the motif has a rather different sequence of ScN70XXK73N74-(X)63-Q137. In addition, the yeast subunit lacks the loop ScF64–N73 of its bovine homologue. With the rather conserved zinc-binding motif in the bovine core-1 subunit, it was expected that the heterodimeric core-1 and core-2 may possess proteolytic activity when it is freed from the bc1 complex. Indeed, the core-1 and core-2 heterodimer of bovine bc1, when treated with triton X-100, displays MPP activity that is divalent metal ion dependent [99] and inhibited by N-terminal signal peptide of the ISP precursor [3].

The dimeric core subunits are anchored to the membrane by recruiting peptide fragments from the N-terminus of subunit 7 and C-terminus of the cyt c1 subunit and incorporating the two peptides into the β sheet in the N-terminal portion of the core-1 subunit (Fig. 5F). Additionally, the N-terminal peptide of the ISP subunit stays in close proximity to the crevice between core-1 and core-2, making additional contacts with the core-1 subunit.

5.2. Structures of other supernumerary subunits

In addition to the two core subunits, smaller supernumerary subunits have also been resolved in various crystal structures. For the bovine complex, structures of all eleven subunits were determined, whereas subunit 11 in avian structures and subunit QCR10, the equivalent of subunit 11 in bovine bc1, in yeast is missing (Table 1). Genetic and biochemical characterizations of supernumerary subunits were often carried out in yeast, illuminating some of their biological functions.

Subunit 6 (also named QPK, 13.4 kDa, QCR7 in yeast) was shown to be on the matrix side of the membrane. It is entirely helical and consists of four helices with connecting loops (Fig. 6A). It attaches on the matrix side to exposed residues of helices F, G, and H of one cyt b subunit in one monomer, while also making contact with core-1 and core-2 of the symmetry-related monomer (Fig. 1A). Because of its position in the bc1 complex, this subunit is conceivably necessary to shield the QN pocket of the cyt b subunit from exposure to the aqueous environment on the matrix side, as partial removal of subunit 6 by proteolysis decouples redox-linked proton pumping [103].

Figure 6. Structures of supernumerary subunits of the Btbc1 complex in ribbon presentation.

(A) Subunit 6, (B) subunit 7, (C) subunit 8, (D) subunit 9, (E) subunit 10, and (F) subunit 11.

Subunit 7 (also named QPC, 9.6 kDa, QCR8 in yeast) was identified as a quinol-binding protein, as it forms adducts with various azido-ubiquinone derivatives [104]. In yeast, mutagenesis of QCR8 indicated an important role of this subunit in the assembly of a functional enzyme and in inhibitor myxothiazol binding, suggesting an impaired QP site [105, 106]. The crystal structure shows that subunit 7 contributes to both the matrix and TM regions. The C-terminal 50 residues of subunit 7 form a long, bent TM helix, and its N-terminal part associates with the core-1 protein as part of a β sheet (Figs. 6B and 5F), serving as one of the membrane anchors for the subunits in the matrix region. The TM portion of the subunit is in direct contact with TM helices G and H of the cyt b subunit, forming a hydrophobic depression that could interact with hydrophobic molecules such as ubiquinone.

Subunit 8 (also called hinge-protein, 9.2 kDa, QCR6 in yeast) was previously thought to support ET from cyt c1 to cyt c by mediating contacts between the two components. This is the only supernumerary subunit that is located on the positive side of the membrane. Crystal structures have confirmed its location and its interaction with the cyt c1 subunit. Subunit 8 is entirely helical, consisting of three helices (Fig. 6C); it forms a hairpin like structure, which is stabilized by a couple of disulfide bonds. The subunit is highly acidic with a large number of glutamate and aspartate residues. In the structure, it exclusively interacts with the cyt c1 subunit (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, in the yeast structure of bc1 complexed with cyt c, subunit QCR6 is not in direct contact with the substrate, calling into question the idea that this subunit mediates interaction between cyt c1 and cyt c.