Abstract

Star-shaped polymer micelles have good stability against dilution with water, showing promising application in drug delivery. In this work, biodegradable micelles made from star-shaped poly(å-caprolactone)/poly(ethylene glycol) (PCL/PEG) copolymer were prepared and used to deliver doxorubicin (Dox) in vitro and in vivo. First, an acrylated monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone) (MPEG-PCL) diblock copolymer was synthesized, which then self-assembled into micelles, with a core-shell structure, in water. Then, the double bonds at the end of the PCL blocks were conjugated together by radical polymerization, forming star-shaped MPEG-PCL (SSMPEG-PCL) micelles. These SSMPEG-PCL micelles were monodispersed (polydispersity index = 0.11), with mean diameter of ≈25 nm, in water. Blank SSMPEG-PCL micelles had little cytotoxicity and did not induce obvious hemolysis in vitro. The critical micelle concentration of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles was five times lower than that of the MPEG-PCL micelles. Dox was directly loaded into SSMPEG-PCL micelles by a pH-induced self-assembly method. Dox loading did not significantly affect the particle size of SSMPEG-PCL micelles. Dox-loaded SSMPEG-PCL (Dox/SSMPEG-PCL) micelles slowly released Dox in vitro, and the Dox release at pH 5.5 was faster than that at pH 7.0. Also, encapsulation of Dox in SSMPEG-PCL micelles enhanced the anticancer activity of Dox in vitro. Furthermore, the therapeutic efficiency of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL on colon cancer mouse model was evaluated. Dox/SSMPEG-PCL caused a more significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth than did free Dox or controls (P < 0.05), which indicated that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL had enhanced anticolon cancer activity in vivo. Analysis with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) showed that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL induced more tumor cell apoptosis than free Dox or controls. These results suggested that SSMPEG-PCL micelles have promising application in doxorubicin delivery for the enhancement of anticancer effect.

Keywords: drug delivery, star-shaped polymer, MPEG-PCL, CMC

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem in the developed countries and many developing countries, and one in four deaths in the United States is due to cancer. There will be 1,638,910 new cancer cases and 577,190 deaths from cancer in the USA in 2012.1 During the most recent 5 years for which there are data (2004–2008), overall cancer incidence rates declined slightly in men (by 0.6% per year) and were stable in women, while cancer death rates decreased by 1.8% per year in men and by 1.6% per year in women. So cancer remains a major disease, and the search for ways to improve the life quality of cancer patients is still a focus.

The application of nanotechnology to drug delivery accounts for the main part of nanomedicine.2,3 For example, nanotechnology can improve the solubility of hydrophobic drug to overcome the problem of system administration4,5 and can selectively deliver drugs to target tissues or cells,6 etc. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles have been high-lighted as drug delivery systems.7–10 Nanoparticulate systems, self-assembled from amphiphilic block copolymers, provide a unique core-shell architecture, in which the hydrophobic core can serve as a natural carrier environment for hydrophobic drugs while the hydrophilic shell allows particle stabilization in aqueous solution.11–13 Currently, some anticancer drugs delivered by biodegradable polymer nanoparticles, such as paclitaxel, are in clinical research.14

The concentration at which micelles are formed in solution is known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC). The CMC can characterize the stability of polymeric nanoparticles against dilution with water. Generally, a lower CMC suggests better stability of nanoparticles in water. To our knowledge, intravenously administrated nanoparticles are quickly diluted in the bloodstream. Nanoparticles with high CMC disaggregate during dilution, leading to a fast burst-release of drugs. Thus, polymeric nanoparticles with low CMC attract some attention as drug delivery systems, and some attempts have been made to reduce the CMC of micelles, with use of nuclear cross-linked micelles,15,16 shell cross-linked micelles,17 and so on.

The monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone) (MPEG-PCL) diblock copolymer is composed of a monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol) (MPEG) segment and poly(å-caprolactone) (PCL) segment. PCL is a biodegradable, biocompatible, and semicrystalline polymer with a very low glass transition temperature. PEG is hydrophilic, nontoxic, and nonimmunogenic.18,19 Therefore, the MPEG-PCL copolymer is biodegradable and biocompatible. The MPEG-PCL micelle is nontoxic, easy to produce, monodispersed and appropriately small. MPEG-PCL micelles can increase the water solubility of hydrophobic chemotherapeutic agents, such as curcumin.20 MPEG-PCL also can deliver gene and protein antigen.21,22 So, lowering the CMC of MPEG-PCL can improve its stability during dilution, which can improve its potential application in drug delivery. Compared with linear copolymer micelles, star-shaped copolymer micelles have many characteristic properties that are due to their unique structure. Firstly, the star-shaped copolymers have a smaller hydrodynamic radius and lower solution viscosity in comparison with linear polymers of the same molecular weight and composition. More importantly, the unimolecular micelles prepared from the star-shaped copolymer have greater micelle stability over those prepared from linear polymers In this work, we used the nuclear cross-linking method to improve the stability of MPEG-PCL.

Doxorubicin (Dox) is one of the most widely prescribed and effective anticancer drugs. However, Dox is inappropriate as a chemotherapeutic agent, due to its short- and long-term cardiac toxicity.23,24 Thus, it is interesting to improve the anticancer activity and reduce the systemic toxicity of Dox with development of a drug delivery system.25–28 In this article, we designed a novel self-assembled star-shaped MPEG-PCL (SSMPEG-PCL) micelle with low CMC and encapsulated Dox in the SSMPEG-PCL micelles using a pH-induced self-assembly method without using any organic solvents and surfactants. The Dox loaded SSMPEG-PCL (Dox/SSMPEG-PCL) micelles may be a novel formulation of Dox, with potential application in cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Materials

å-Caprolactone (å-CL), acryloyl chloride, and stannous octoate (Sn(Oct)2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Both 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), also from Sigma-Aldrich, were used without further purification.

All other chemicals and solvents were purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Factory (Chengdu, People’s Republic of China), and they were all analytical reagent (AR) grade.

Synthesis of SSMPEG-PCL micelles

Preparation of MPEG-PCL copolymers

MPEG (molecular weight = 2000) (Sigma-Aldrich) was dried in a one-necked flask under vacuum and magnetically stirred at 105°C for 90 minutes before use. MPEG-PCL (molecular weight = 4000) was prepared by ring-opening of å-caprolactone, initiated by MPEG as reported previously.29

Preparation of acrylated MPEG-PCL (AMPEG-PCL) copolymers

Briefly, 10 g of MPEG-PCL was dissolved in 40 mL methylene chloride, followed by the addition of 0.2 mL of triethylamine. Then, 0.8 mL of acryloyl chloride was dropped into this solution. The system was stirred at a constant speed (600 r/min) at room temperature (20°C). After 24 hours, the reaction products were precipitated using excess cold petroleum ether, three times. The precipitate was dissolved in excess distilled water and purified by dialysis for 72 hours. The final solution was freeze dried.

Preparation of SSMPEG-PCL micelles

AMPEG-PCL (1.2 g) copolymer was dissolved in distilled water (10 mL) at 60°C; then K2S2O8 (4 wt% of polymer) was added into this mixture, with a constant stirring speed (600 r/min). Samples were taken out at different time intervals and purified by dialysis. These samples were examined by nuclear magnetic resonance analysis and gel permeation chromatography, to determine the molecular structure and molecular weight, respectively.

Preparation of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles

Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were prepared by the pH-induced self-assembly method.30 Briefly, 1.4 mL of SSMPEG-PCL micelles prepared in the previous step were placed into a tube, and 0.2 mL of special phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (at pH 7.4 and 10 × the usual concentration) was added into this solution, under stirring. Then, 0.4 mL of Dox aqueous solution (5 mg/mL) was dropped into the above solution. Because of the low solubility of Dox in PBS at pH 7.4, Dox self-assembled into the hydrophobic core of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles. After 20 minutes, Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were obtained.

Characterization of the physicochemical properties of prepared polymer and micelles

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) analysis

1H-NMR spectra (in CDCl3 solvent) were recorded on a Varian 400 spectrometer (Varian Medical Systems Inc, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 400 MHz, to characterize the chemical composition of the reaction products.

Gel permeation chromatography

Gel permeation chromatography (110 HPLC; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to determine macromolecular weight of the SSMPEG-PCL copolymers. SSMPEG-PCL copolymer was dissolved in freshly distilled tetrahydrofuran, at a concentration of 1–2 mg/mL. The tetrahydrofuran was eluted at a rate of 1.0 mL/min through two Waters (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA) Styragel® HT columns and a linear column. The internal and column temperatures were kept at 35°C. The macromolecular weight was calculated from the elution volume of polystyrenes with narrow molecular weight distribution.

Particle size determination

Particle size distribution spectra of micelles were determined using a laser diffraction particle size detector (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The temperature was kept at 25°C during the measuring process. All results were the mean of three test runs.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

The morphology of the prepared micelles was observed under a TEM (H-6009IV; Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan): micelles were diluted with distilled water and placed on a copper grid covered with nitrocellulose. The sample was negatively stained with phosphotungstic acid and dried at room temperature.

Drug loading (DL) and encapsulation efficiency (EE) assay

The EE and DL of the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were determined by a subtraction method. Briefly, 0.2 mL of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle solution was centrifuged through a filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 3 kDa. Free Dox could pass through the filter, but SSMPEG-PCL micelle-encapsulated Dox could not pass through the filter. Unincorporated Dox in the filtered solution was quantified by determining the absorbance at 485 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectramax M5, Molecular Devices Corp, Sunnyvale, CA). DL and EE were calculated as in previous reports,31 using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The micelle solution was stored at 4°C for 1 month to test the stability of SSMPEG-PCL.

CMC assay

The CMC of the MPEG-PCL and SSMPEG-PCL micelles was determined using a fluorescence technique with pyrene as a probe. Pyrene is probably the most widely used fluorescence probe, as its emission characteristics (ratio of intensities of the first [373 nm] and third [384 nm] peaks; I1/I3) are sensitive to the polarity level of its environment. For the measurement of CMC, the micellar solutions loaded with pyrene were prepared as follows: solution of pyrene in ethanol (0.1 mg/mL × 12 μL) was added to each of a series of 10 mL vials, and the ethanol was evaporated at 60°C. Then, 10 mL of different concentrations of prepared micellar solution was added into each vial, and the pyrene concentration in the final solution was kept at 1.2 × 10−4 mg/mL. The stoppered vials were heated for 3 hours at 65°C to equilibrate the pyrene and the micelles and subsequently allowed to cool overnight to room temperature. For fluorescence measurement, using pyrene as the fluorescent probe, excitation was done at 334 nm, and emissions were recorded in the 340-450 nm wavelength range. The slit widths for both excitation and emission were fixed at 3 nm.

Cytotoxicity of SSMPEG-PCL micelles and Dox/SSMPEG-PCL

The cytotoxicity of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles on HEK293 cells was evaluated using the MTT method. Briefly, 293 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well, in 100 μL DMEM medium, in 96-well plates and grown for 24 hours. The cells were then exposed to a series of SSMPEG-PCL micelle solutions at different concentrations for 24 hours and 48 hours, and the viability of cells was measured using the MTT method.

The cytotoxicity of free Dox or micelle-encapsulated Dox on the colon cancer CT-26 cell line was evaluated by the MTT method. Briefly, CT-26 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well, in 100 μL of RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), in 96-well plates and grown for 24 hours. Cells were then exposed to a series of free Dox or micelle-encapsulated Dox solutions at different concentrations for 48 hours. The viability of cells was measured using the MTT method. The results were the mean of six test runs.

Hemolytic test in vitro

The hemolytic study32,33 was performed on SSMPEG-PCL micelles in vitro. Briefly, 0.5 mL of SSMPEG-PCL micelles (100 mg/mL) in normal saline was diluted into 2.5 mL with normal saline and added into 2.5 mL of rabbit erythrocyte suspension (2%) in normal saline, at 37°C. Normal saline and distilled water were employed as negative and positive controls, respectively. After 3 hours, the erythrocyte suspension was centrifuged and the color of the supernatant was compared with that of the controls.

Release of Dox from the SSMPEG-PCL micelles

The in vitro release behavior of Dox from the drug loaded SSMPEG-PCL micelles was studied using a modified dialysis method,34,35 which was shown as following: 0.5 mL Dox-loaded micelle solutions were transferred into a dialysis membrane (MWCO 3000), and 0.5 mL of free Dox solution in water (0.25 mg/mL) was used as the control. Then solutions were dialyzed against 25 mL acetic acid sodium buffer at pH 5.5 and phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, both containing Tween® 20 (0.5%), at 37°C with gentle shaking. A total of 25 mL of the surrounding dialysis medium was removed at predetermined time points for analysis, and 25 mL of fresh buffer at the relevant pH was added to the dialysis medium. The released Dox from Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles was able to infiltrate through the dialysis bag because the molecular weight of the Dox was less than 3000. However, Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles could not come out because their molecular weight was much larger than 3000. The released Dox was quantified by determining absorbance at 485 nm using the spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices Corp). This study was repeated three times, and the results were expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (SD).

Evaluation of the anticancer effect of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles in vivo

Seven-week-old female BALB/c mice (Vital River, Beijing, People’s Republic of China) were used in present study. CT26 cells (1 × 106) were inoculated into the subcutaneous of the mice. When tumors grew up to approximately 100 mm3, mice were randomly divided into four groups (five mice per group). Normal salts (NS), free Dox (Dox: 5mg/kg), Dox/SSMPEG-PCL (Dox: 5mg/kg) or SSMPEG-PCL (Control) were intravenously administered. Tumor volumes were assessed by bilateral vernier caliper measurement every 3 days and calculated according to the equation:

| (3) |

where a represented the shorter and b represented the longer of the two dimensions.

Apoptosis analysis

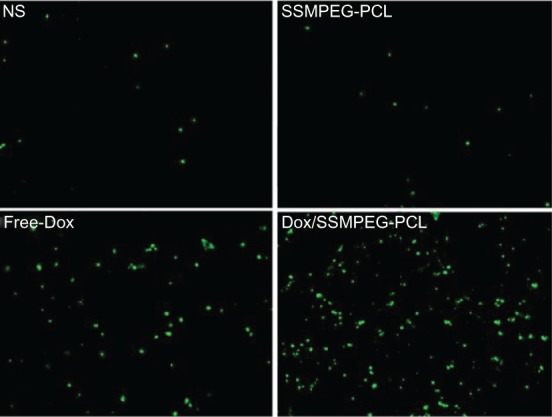

A commercially available terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) kit (Promega Corp, Fitchburg, G3250, WI, USA) was used to analyze apoptotic cells within the CT26 tumors. This analysis was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol; the samples were examined with a fluorescence microscope (×400).

Results and discussion

In this paper, we prepared novel SSMPEG-PCL micelles and used it to deliver doxorubicin with the goal of improving the anticancer effect of doxorubicin.

Preparation and characterization of SSMPEG-PCL micelles

Preparation of SSMPEG-PCL micelles

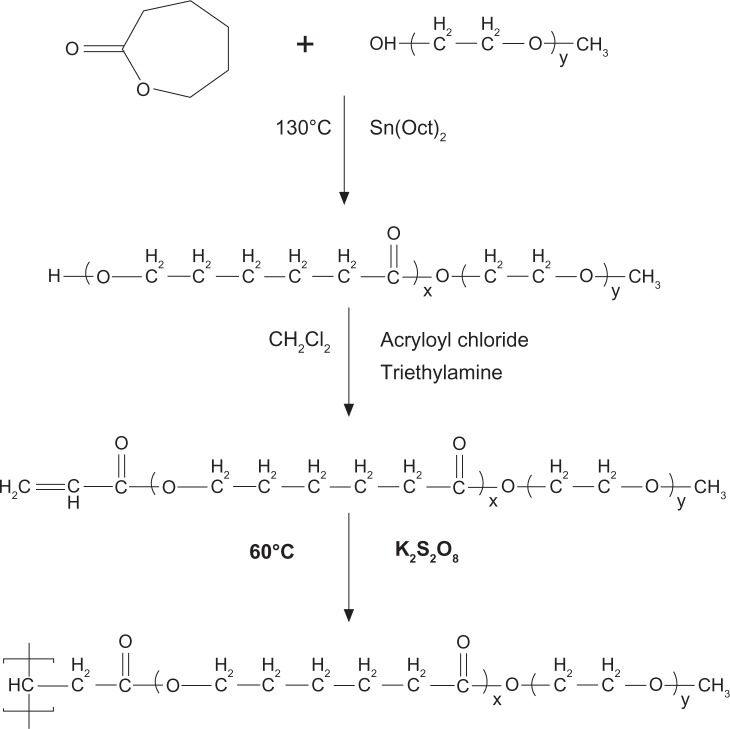

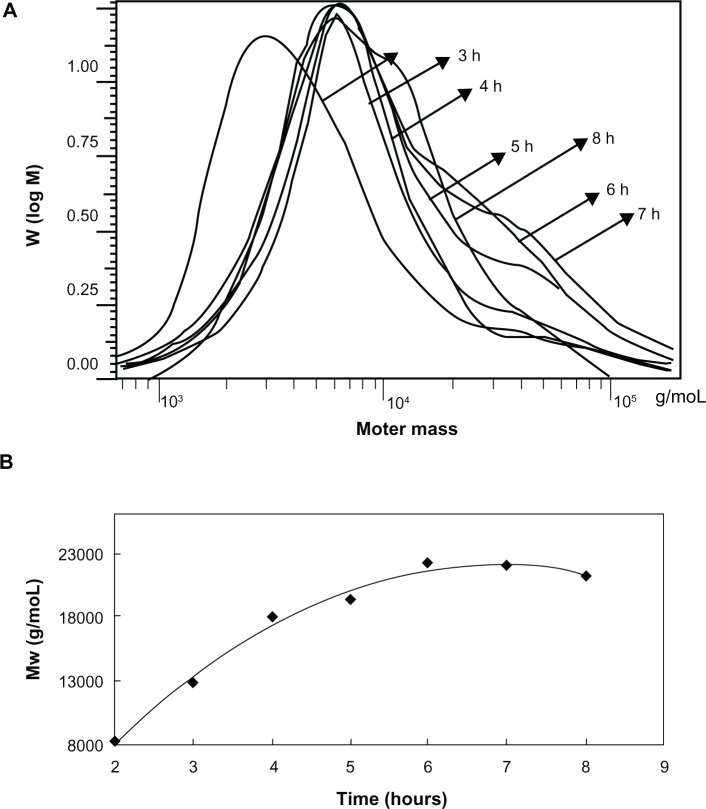

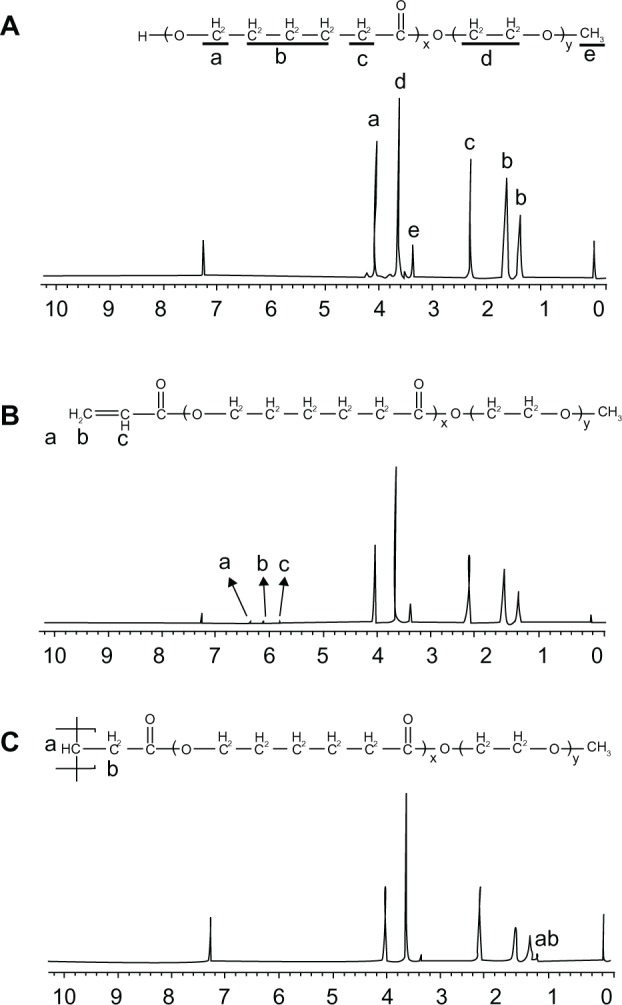

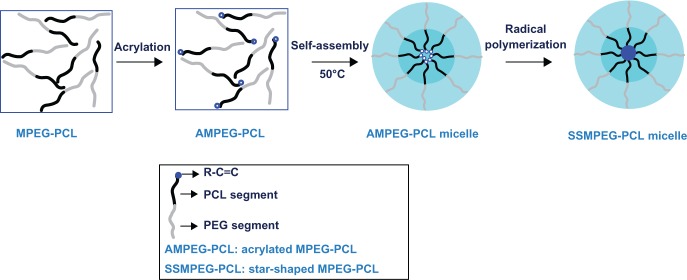

SSMPEG-PCL syntheses were prepared by three steps; and the preparation scheme was presented (Figure1). First, AMPEG-PCL was synthesized. Then, self-assembled AMPEG-PCL micelles were prepared just by heating. Last, SSMPEG-PCL micelles were prepared by radical polymerization of AMPEG-PCL micelles. Also, the chemical reactions involved in preparation of SSMPEG-PCL micelles were presented in Figure 2. To determine the degree of radical polymerization of AMPEG-PCL with time, we determined the molecular weight of SSMPEG-PCL micelles after different polymerization time. As shown in Figure 3, the molecular weight of SSMPEG-PCL increased with time over 6 hours, and no longer increased after 6 hours; this implied that 6 hours may be the rational reaction time for polymerization of AMPEG-PCL. Moreover, 1H NMR was used to determine the structure of MPEG-PCL, AMPEG-PCL and SSMPEG-PCL and results were shown in Figure 4. The 1H NMR spectrum showed that peaks at 1.40, 1.65, 2.32, and 4.06 ppm were assigned to the methylene protons of ¯(CH2)3¯, ¯OCCH2¯, and ¯CH2COŌ in the PCL units, respectively. The sharp peak at 3.65 ppm was attributed to the methylene protons of ¯CH2CH2Ō in the MPEG units in the block copolymer. The very weak peak at 3.38 was attributed to the methyl protons of ¯CH3 in the MPEG units. Compared with the 1H-NMR spectrum of the MPEG-PCL copolymer (Figure 4A), the AMPEG-PCL copolymers (Figure 4B) exhibited distinct resonance signals, a, b, and c. The peaks a, b, and c were the three hydrogens of CH2=CH̄. This indicated that AMPEG-PCL was prepared successfully. Then AMPEG-PCL micelles polymerized into SSMPEG-PCL micelles, using K2S2O8 as initiator. The prepared SSMPEG-PCL copolymers were characterized by 1H-NMR in Figure 4C. Compared with Figure 4B, in Figure 4C, the peaks a, b, and c (CH2·CH̄) were not present in this spectrum. The absence of (CH2 CH̄) strongly demonstrated the exact linkage structures between double bonds, and this indicated that SSMPEG-PCL was successfully prepared.

Figure 2.

Synthesis scheme of star-shaped MPEG-PCL.

Notes: First, MPEG-PCL was prepared by ring-opening of å-caprolactone, initiated by MPEG. Then, MPEG-PCL was acrylated to be AMPEG-PCL; last, AMPEG-PCL micelles were polymerized into SSMPEG-PCL micelles.

Abbreviations: AMPEG, acrylated MPEG; MPEG-PCL, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); MPEG, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL.

Figure 3.

Gel permeation chromatography of SSMPEG-PCL.

Notes: The molecular weight of SSMPEG-PCL increased with time over 6 hours. After 6 hours, the molecular weight no longer increased with the time, which illustrated that the reaction was completed in 6 hours.

Abbreviation: SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL; MW, molecular weight.

Figure 4.

1H-NMR spectra of (A) MPEG-PCL copolymer, (B) AMPEG-PCL copolymer, and (C) SSMPEG-PCL copolymer. (A) The peaks at 1.40, 1.65, 2.32, and 4.06 ppm were assigned to the methylene protons of ¯(CH2)3¯, ¯OCCH2¯ and ¯CH2COŌ in the PCL units, respectively. The sharp peak at 3.65 ppm was attributed to the methylene protons of ¯CH2CH2Ō in the MPEG units in the block copolymer. The very weak peak at 3.38 was attributed to the methyl protons of ¯CH3 in the MPEG units; (B) AMPEG-PCL copolymers exhibited distinct resonance signals a, b, and c compared with the 1H-NMR spectrum of the MPEG-PCL copolymer. The peaks at a, b, and c were the three hydrogens of CH2=CH̄. This indicated that AMPEG-PCL was prepared successfully. Second, AMPEG-PCL was self-assembled into AMPEG-PCL micelles; (C) Then AMPEG-PCL micelles polymerized into SSMPEG-PCL micelles, using K2S2O8 as initiator.

Notes: The peaks of (CH2·CH̄) were not present in this spectrum. The absence of (CH2·CH̄) strongly demonstrated the exact linkage structures between double bonds, and this indicated that SSMPEG-PCL was successfully prepared.

Abbreviations: 1H-NMR, proton nuclear magnetic resonance; MPEG-PCL, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); AMPEG-PCL, acrylated MPEG-PLC; SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL; PCL, poly(å-caprolactone); MPEG, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol).

Characterization of SSMPEG-PCL micelles

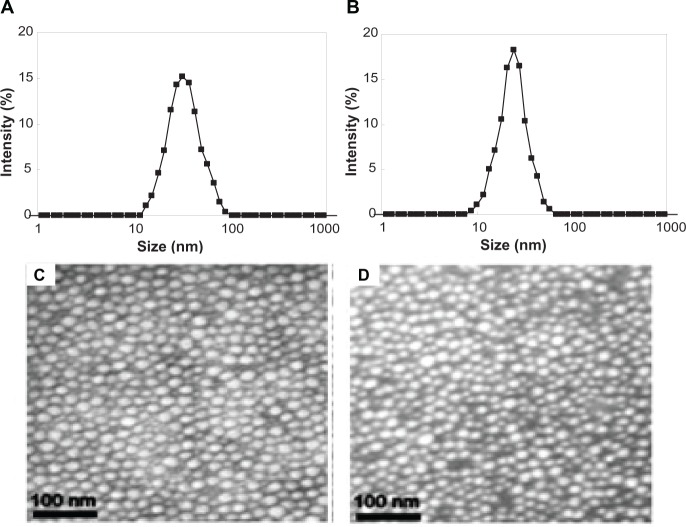

These SSMPEG-PCL micelles were characterized in detail. In Figure 5, the particle size distribution spectrum of freshly prepared AMPEG-PCL micelles and SSMPEG-PCL micelles were presented; this indicated that AMPEG-PCL micelles had a very narrow particle size distribution and had a mean particle size of 35.9 + 1.2 nm (polydispersity index [PDI] = 0.12 + 0.02). According to the TEM image of the AMPEG-PCL micelles (Figure 5C), these micelles were spherical and monodispersed, with a mean diameter of≈23.3 nm. However, SSMPEG-PCL micelles had a more narrow particle size distribution and had a mean small particle size of 25.23 + 2.3 nm (PDI = 0.09 + 0.03). And in the TEM image of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles (Figure 5D), these micelles were spherical and monodispersed with a mean diameter of ≈18.3 nm. It may be that the micelles shrank as a result of radical polymerization, resulting in the particle size decrease. To our knowledge, TEM determines the size of dry particles, while dynamic light scattering determines the hydrodynamic diameter of particles in water. So, the size determined by TEM may be smaller than that exam by dynamic light scattering measurement.

Figure 5.

Characterization of AMPEG-PCL micelles and SSMPEG-PCL micelles. (A) Size distribution of AMPEG-PCL micelles; (B) size distribution of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles; (C) TEM image of the AMPEG-PCL micelles; (D) TEM image of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles.

Abbreviations: AMPEG-PCL, acrylated monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped acrylated monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

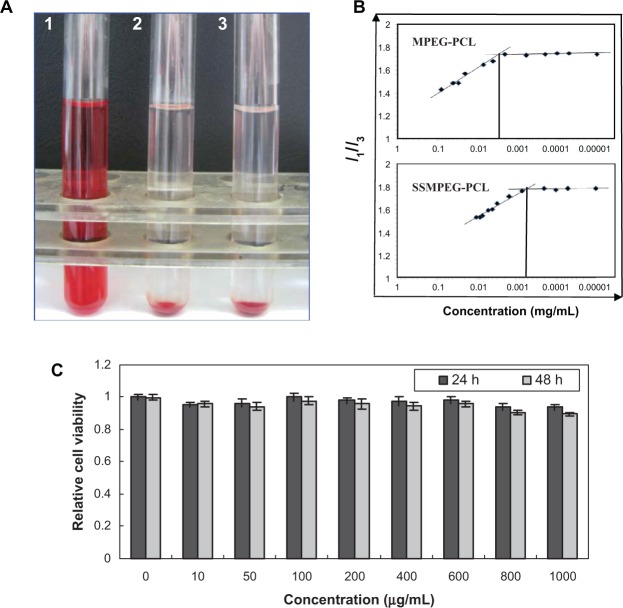

Cytotoxicity of SSMPEG-PCL micelles and hemolytic test in vitro

In the hemolytic study, if the supernatant solution was absolutely achromatic, it was implied that SSMPEG-PCL micelles did not induce any hemolysis. In contrast, SSMPEG-PCL micelles were shown to have induced hemolysis if the supernatant solution was red. The hemolytic study of SSMPEG-PCL micelles was performed, and the result implied that SSMPEG-PCL micelles (100 mg/mL) did not induce hemolysis in vitro (Figure 6A). Moreover, it was found that SSMPEG-PCL micelles did not greatly affect the cell viability of HEK293 cells, at a concentration lower than 1 mg/mL (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Safety assessment of blank MPEG-PCL micelles. (A) Observation of the result of the hemolytic study on MPEG-PCL micelles (1, distilled water used as positive control; 2, SSMPEG-PCL micelles at the concentration of 100 mg/mL; 3, normal saline used as the negative control); (B) CMC of MPEG-PCL and SSMPEG-PCL; (C) cytotoxicity of SSMPEG-PCL micelles on HEK293 cells.

Note: This illustrated that SSMPEG-PCL did not cause hemolysis and had no toxicity in normal cells, which indicated that SSMPEG-PCL was a safe vector.

Abbreviations: MPEG-PCL, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); CMC, critical micelle concentration; SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL.

CMC assay

To determine the stability of SSMPEG-PCL micelles against dilution in water, the CMC of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles was determined by a fluorescence technique using pyrene as a probe. In Figure 6B, the I1/I3 changed as the concentration of micelles, the CMC was determined as the graphical intersection point. It was observed that the CMC value of SSMPEG-PCL (6 × 10−4 mg/mL) was much lower than that of MPEG-PCL (3 × 10−3 mg/mL). This means that SSMPEG-PCL micelles are more stable than MPEG-PCL micelles against dilution. Also, the stability of SSMPEG-PCL micelles against storage at 4°C was studied. Results indicated that the particles size of SSMPEG-PCL micelle did not significantly changed in one month. To determine the stability of SSMPEG-PCL micelles against dilution in water, the CMC of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles was determined by a fluorescence technique using pyrene as a probe. In Figure 6B, the I1/I3 changed as the concentration of micelles, the CMC was determined as the graphical intersection point. It was observed that the CMC value of SSMPEG-PCL (6 × 10−4 mg/mL) was much lower than that of MPEG-PCL (3 × 10−3 mg/mL). This means that SSMPEG-PCL micelles are more stable than MPEG-PCL micelles against dilution. Also, the stability of SSMPEG-PCL micelles against storage at 4°C was studied. Results indicated that the particles size of SSMPEG-PCL micelle did not significantly changed in one month.

Preparation and characterization of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles

Preparation of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles

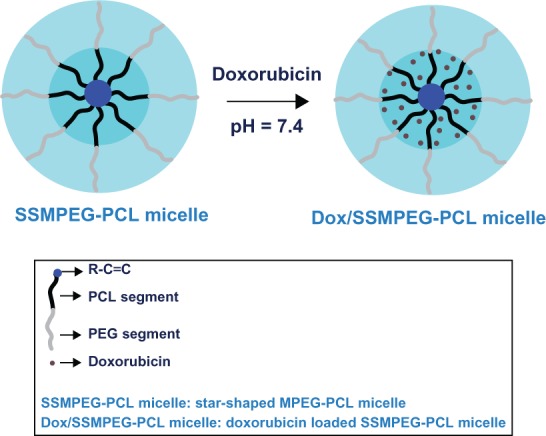

We encapsulated Dox in SSMPEG-PCL micelles by a novel self-assembly procedure (shown schematically in Figure 7). These SSMPEG-PCL micelles had a core-shell structure: a hydrophobic PCL core coated by a hydrophilic PEG shell.30 After empty SSMPEG-PCL micelles were obtained, Dox was loaded into the SSMPEG-PCL micelles by a pH-induced self-assembly method. To our knowledge, Dox can be well dissolved in distilled water (at pH 5–6, the solubility is 10 mg mL−1), but the solubility of Dox in PBS at pH 7.4 is very low. Meanwhile, amphiphilic block polymeric micelles always have a loose structure in water. After Dox aqueous solution was dropped into the SSMPEG-PCL micelles in PBS (pH 7.4), under stirring, the Dox became hydrophobic and self-assembled into the hydrophobic cores of the SSMPEG-PCL micelles. This procedure for preparing Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles was very simple and easy to scale up. Meanwhile, no surfactants, organic solvents, or vigorous stirring were applied in this procedure.

Figure 7.

Preparation scheme for Dox-loaded SSMPEG-PCL nanoparticles.

Notes: Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were prepared in two steps. First, blank SSMPEG-PCL micelles were prepared by a self-assembly method. Then, Dox was incorporated into the SSMPEG-PCL micelles through a pH-induced self-assembly method. Briefly, 0.1 mL of PBS (10×, pH = 7.4) was added into 0.7 mL of blank MPEG-PCL micelle solution (30 mg·mL−1), followed by dropping 0.2 mL of Dox aqueous solution (5 mg·mL−1) into the above MPEG-PCL micelle solution under moderate stirring. After 1 hour, Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were obtained.

Abbreviations: Dox, doxorubicin; SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); Dox/SSMPEG-PCL, Dox-loaded SSMPEG-PCL; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; MPEG-PCL monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); PCL, poly(å-caprolactone); PEG, poly (ethylene glycol).

Characterization of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles

The physicochemical properties of the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were characterized in detail. To determine the drug EE, a filter, with MWCO of 3 kDa, was employed to separate free Dox from the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle solution. This filter only allowed free Dox, but not Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles, to be filtered. After free Dox (1 mg · mL−1) or Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle solution (1 mg · mL−1) was centrifuged with the filter, the lighter red color of the filtered solution implied that the main part of Dox in the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle solution was present as Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles but not free Dox. Further quantitative assay indicated that the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles had a drug EE of 93.6% ± 1.3% and a DL of 4.53% ± 0.5%.

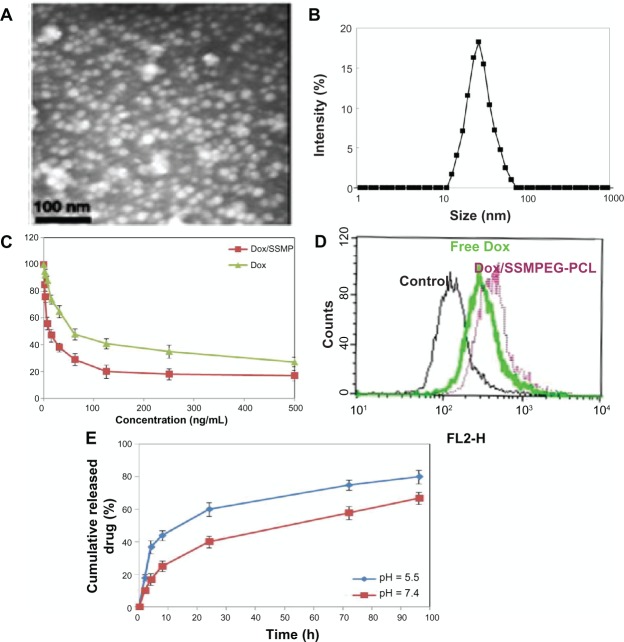

The particle size distribution spectrum of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles is presented in Figure 8 A. These micelles were monodispersed (PDI = 0.129 ± 0.03), and had a mean particle size of 30.1 ± 1.7 nm. The morphology of the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles, determined by TEM is shown in Figure 8B. It was found that the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles were monodispersed and spherical with a diameter of 21 nm.

Figure 8.

Characterization of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles. (A) TEM image of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles; (B) particle size distribution of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles, determined by a laser diffraction size detector; (C) cytotoxicity of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles or free Dox on CT26 cells; (D) cellular uptake of free Dox and Dox/MPEG-PCL micelles in C-26 cells: Dox-derived fluorescence intensity of C-26 cells after 6 hours of exposure to 50 ng/mL of Dox or Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle solution. (E) in vitro release profile of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles at pH 5.5 or 7.4.

Abbreviations: Dox/SSMPEG-PCL, doxorubicin-loaded star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; Dox, doxorubicin.

The in vitro cytotoxicity of SSMPEG-PCL micelle-encapsulated Dox and free Dox was studied on C-26 cells using the MTT method. As shown in Figure 8C, the values of the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of DOX loaded SSPEG-PCL and DOX against CT-26 cells were 16.5 ng and 59.7 ng, respectively. The cytotoxicity of SSMPEG-PCL micelle-encapsulated Dox was stronger than that of free Dox. This result indicates that encapsulation of Dox in SSMPEG-PCL micelles enhanced the cytotoxicity of Dox. Moreover, we tested the cellular uptake of Dox using flow cytometry. In Figure 8D, we found that CT-26 cell uptake of Dox was greater in the Dox-SSMEG-PCL group. So, the enhanced cytotoxicity may be caused by the increased cellular uptake and the specific structure of the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles.

The in vitro release profile of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles was studied using a dialysis method. As shown in Figure 8E, Dox was released from Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles over an extended period. Meanwhile, Dox release from Dox/SSMPEG-PCL was faster at pH 5.5 than that at pH 7.0. This pH-dependent releasing behavior might be mainly due to the protonation of the amino group of Dox at lower pH. This pH-dependent release behavior provides a very interesting possibility for achieving tumor-targeted Dox delivery with nanovectors. It is expected that Dox could be slowly released in plasma under normal physiological conditions (pH 7.4) but quickly released at the solid tumor site (pH 5.5).

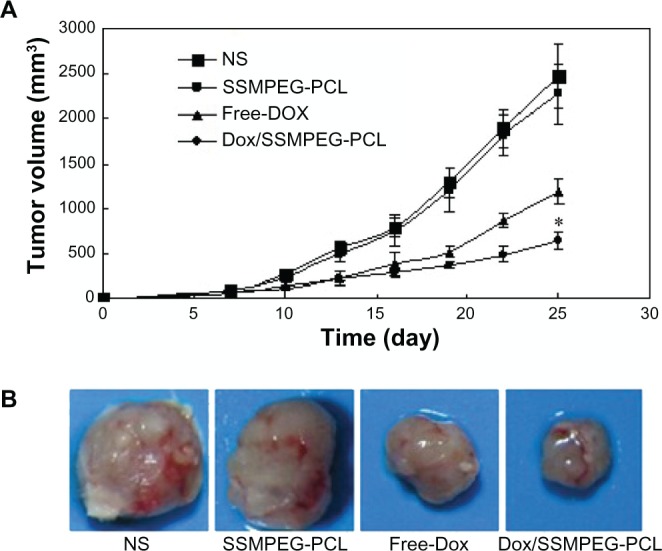

Antitumor effect of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles in vivo

A mouse subcutaneous colon cancer model was employed to study the effect of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles on tumor growth inhibition. Tumor-bearing mice were assigned randomly to four groups and treated with NS, SSMPEG-PCL, free Dox, and Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles by intravenous injection. Tumor volume was recorded every 3 days. The tumor growth curves of each group are presented in Figure 9A. Results indicated that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles treatment resulted in smaller tumor volume compared with the other treatments. A representative tumor in each group is presented in Figure 9B. We can clearly observe that the tumor in the group treated with Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles was smaller than those in of the other groups. This in vivo study indicates that: (1) systemic application of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles (5 mg·kg−1) inhibited the growth of subcutaneous C-26 colon carcinoma in vivo; and (2) encapsulation of Dox in SSMPEG-PCL micelles enhanced the anticancer activity of Dox in vivo.

Figure 9.

Antitumor effect of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL in vivo. (A) Tumor development curve. Female mice were inoculated with C-26 cells on day 0. On day 7, the mice were randomized into four groups, and were injected intravenously with saline (NS), empty SSMPEG-PCL micelles, free Dox, or Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles. (B) Representative photos of tumors in each treatment group on day 25.

Notes: This indicated that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL could more effectively inhibit the growth of colon tumor than free Dox. Asterisk denotes significant differences between treatment groups (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: Dox/SSMPEG-PCL, doxorubicin-loaded star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); Dox, doxorubicin.

To study the mechanism associated with the anticancer activity of Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles in vivo, a TUNEL assay was carried out. As shown in Figure 10, many strongly positive nuclei identified as apoptotic could be observed in the Dox/SSMPEG-PCL-treated tumor tissues, whereas such nuclei were rare in the NS and SSMPEG-PCL groups, through TUNEL assay. This indicated that induction of apoptosis may be one mechanism for the enhanced inhibition of colon cancer by Dox/SSMPEG-PCL in vivo.

Figure 10.

Detection of apoptotic tumor cells by TUNEL assay.

Notes: The assay confirmed that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL (5 mg/kg) induced more cancer cell apoptosis than did saline (NS), empty SSMPEG-PCL micelles (SSMPEG-PCL), and free Dox (5 mg/kg). This indicated that Dox/SSMPEG-PCL induced more cancer cell apoptosis than free Dox, in vivo.

Abbreviations: TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling; Dox/SSMPEG-PCL, doxorubicin-loaded star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); Dox, doxorubicin.

In attempting to improve the stability of MPEG-PCL micelles against dilution, we cross-linked the core of MPEG-PCL micelles, creating SSMPEG-PCL micelles with low CMC than that of MPEG-PCL micelles. Moreover, encapsulation of Dox in SSMPEG-PCL micelles improved the anticancer effect of Dox in vitro and in vivo. These results indicate that SSMPEG-PCL micelles have promising application in anticancer drug delivery. Also, Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelles may be a new doxorubicin formulation and deserve future study.

Conclusion

In this study, SSMPEG-PCL micelles were successfully prepared. These micelles were biodegradable, stable, monodispersed, low toxic, and original. The SSMPEG-PCL micelle shows potential for application as a Dox-delivery system. The Dox/SSMPEG-PCL micelle was shown to enhance anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo, and might be a novel anticancer agent.

Figure 1.

Preparation scheme for star-shaped MPEG-PCL micelles.

Notes: First, MPEG-PCL was acrylated to become AMPEG-PCL; then, AMPEG-PCL self-assembled into AMPEG-PCL micelles. At last, AMPEG-PCL micelles were polymerized into SSMPEG-PCL micelles.

Abbreviations: MPEG-PCL, monomethoxy poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(å-caprolactone); SSMPEG-PCL, star-shaped MPEG-PCL; PCL, poly(å-caprolactone); PEG, poly (ethylene glycol).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20110181120087), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81201785 and No 30671963), CMB 98681, National Science and Technology Major Project (2013ZX09301-304-008) and the National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (2010CB529900).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a delivery system for hydrophobic anticancer drugs. Small. 2007;3(8):1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan R. Polymer conjugates as anticancer nanomedicines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Steeg E, van Esch A, Wagenaar E, et al. High impact of Oatp1a/1b transporters on in vivo disposition of the hydrophobic anticancer drug paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(2):294–301. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svenson S, Wolfgang M, Hwang J, yan J, Eliasof S. Preclinical to clinical development of the novel camptothecin nanopharmaceutical CRLX101. J Control Release. 2011;153(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha R, Kim GJ, Nie S, Shin DM. Nanotechnology in cancer therapeutics: bioconjugated nanoparticles for drug delivery. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(8):1909–1917. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Gao S, Ye WH, Yoon HS, Yang YY. Co-delivery of drugs and DNA from cationic core-shell nanoparticles self-assembled from a biodegradable copolymer. Nat Mater. 2006;5(10):791–796. doi: 10.1038/nmat1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:167–171. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Service RF. Materials and biology. Nanotechnology takes aim at cancer. Science. 2005;310(5751):1132–1134. doi: 10.1126/science.310.5751.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, Amiji M. A review ofstimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J Control Release. 2008;126(3):187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endres TK, Beck-Broichsitter M, Samsonova O, Renette T, Kissel TH. Self-assembled biodegradable amphiphilic PEG-PCL-lPEI triblock copolymers at the borderline between micelles and nanoparticles designed for drug and gene delivery. Biomaterials. 2011;32(30):7721–7731. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou LY, Chan WC. A strategy to assemble nanoparticles with polymers for mitigating cytotoxicity and enabling size tuning. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6(5):767–775. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liechty WB, Peppas NA. Expert opinion: Responsive polymer nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Yang L, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Application of nanotechnology in cancer therapy and imaging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):97–110. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuai X, Merdan T, Schaper AK, Xi F, Kissel T. Core-cross-linked polymeric micelles as paclitaxel carriers. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15(3):441–448. doi: 10.1021/bc034113u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaturanpinyo M, Harada A, Yuan X, Kataoka K. Preparation of bionanoreactor based on core-shell structured polyion complex micelles entrapping trypsin in the core cross-linked with glutaraldehyde. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15(2):344–348. doi: 10.1021/bc034149m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao L, Manners I, Winnik MA. Synthesis and self-assembly of the organic-organometallic diblock copolymer poly(isoprene-b-ferrocenylphenylphosphine): shell cross-linking and coordination chemistry of nanospheres with a polyferrocene core. Macromolecules. 2001;34(10):3353–3360. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Zhang L, Cao Y, Ge H, Jiang X, Yang C. Degradation behavior of poly(epsilon-caprolactone)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(epsilon-caprolactone)micelles in aqueous solution. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(5):1756–1762. doi: 10.1021/bm049845j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gou M, Zheng L, Peng X, et al. Poly(epsilon-caprolactone)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) (PCL-PEG-PCL) nanoparticles for honokiol delivery in vitro. Int J Pharm. 2009;375(1–2):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gou M, Men K, Shi H, et al. Curcumin-loaded biodegradable polymeric micelles for colon cancer therapy in vitro and in vivo. Nanoscale. 2011;3(4):1558–1567. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00758g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang JS, Kim SY, Lee SB, Kim KO, Han JS, Lee YM. Poly(ethylene glycol)/poly(epslon-caprolactone) diblock copolymeric nanoparticles for non-viral gene delivery: the role of charge group and molecular weight in particle formation, cytotoxicity and transfection. J Control Release. 2006;113(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gou ML, Huang MJ, Yong Z, et al. Preparation of anionic poly(epsilon-caprolactone)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) copolymeric nanoparticles as basic protein antigen carrier. Growth Factors. 2007;25(3):202–208. doi: 10.1080/08977190701671613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershman DL, McBride RB, Eisenberger A, Tsai W Y, Grann VR, Jacobson JS. Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3159–3165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae Y, Fukushima S, Harada A, Kataoka K. Design of environmentsensitive supramolecular assemblies for intracellular drug delivery: polymeric micelles that are responsive to intracellular pH change. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42(38):4640–4643. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasongkla N, Shuai X, Ai H, et al. cRGD-functionalized polymer micelles for targeted doxorubicin delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43(46):6323–6327. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CC, Gillies ER, Fox ME, et al. A single dose of doxorubicin-functionalized bow-tie dendrimer cures mice bearing C-26 colon carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(45):16649–16654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607705103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayhew EG, Goldrosen MH, Vaage J, Rustum YM. Effects of liposome-entrapped doxorubicin on liver metastases of mouse colon carcinomas 26 and 38. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78(4):707–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen C, Guo S, Lu C. Degradation behaviors of monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) nanoparticles in aqueous solution. Polym Adv Technol. 2008;19(1):66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gou M, Shi H, Guo G, et al. Improving anticancer activity and reducing systemic toxicity of doxorubicin by self-assembled polymeric micelles. Nanotechnolog y. 2011;22(9):095102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/9/095102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gou M, Zheng X, Men K, et al. Poly(epsilon-caprolactone)/poly(ethylene glycol)/poly(epsilon-caprolactone) nanoparticles: preparation, characterization, and application in doxorubicin delivery. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113(39):12928–12933. doi: 10.1021/jp905781g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gou M, Men K, Zhang J, et al. Efficient inhibition of C-26 colon carcinoma by VSVMP gene delivered by biodegradable cationic nanogel derived from polyethyleneimine. ACS Nano. 2010;4(10):5573–5584. doi: 10.1021/nn1005599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong C, Wang C, Wang Y, et al. Efficient inhibition of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis by drug loaded micelles in thermosensitive hydrogel composites. Nanoscale. 2012;4(10):3095–3104. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30278k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang BL, Gao X, Men K, et al. Treating acute cystitis with biodegradable micelle-encapsulated quercetin. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2239–2247. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Men K, Liu W, Li L, et al. Delivering instilled hydrophobic drug to the bladder by a cationic nanoparticle and thermo-sensitive hydrogel composite system. Nanoscale. 2012;4(20):6425–6433. doi: 10.1039/c2nr31592k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]