Abstract

This article briefly reviews the current state of therapy for older patients with prostate cancer and provides a call-to-action highlighting the need for an improved global standard of care in this patient population.

Keywords: Call to action, Optimizing management, Patient care, Senior adults

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed male cancer in developed countries [1]. With a total of 89,319 deaths in 2008, it represents the third leading cause of male cancer deaths in Europe, after lung and colorectal cancer [2]. It is the second leading cause of male cancer death in the U.S. [3]. Prostate cancer affects predominantly senior adults (i.e., men aged 75 years or older) [4]. According to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Medicare database, median age at diagnosis in the U.S. is 67 years, and about two out of three deaths due to prostate cancer occur at the age of 75 years or older [4].

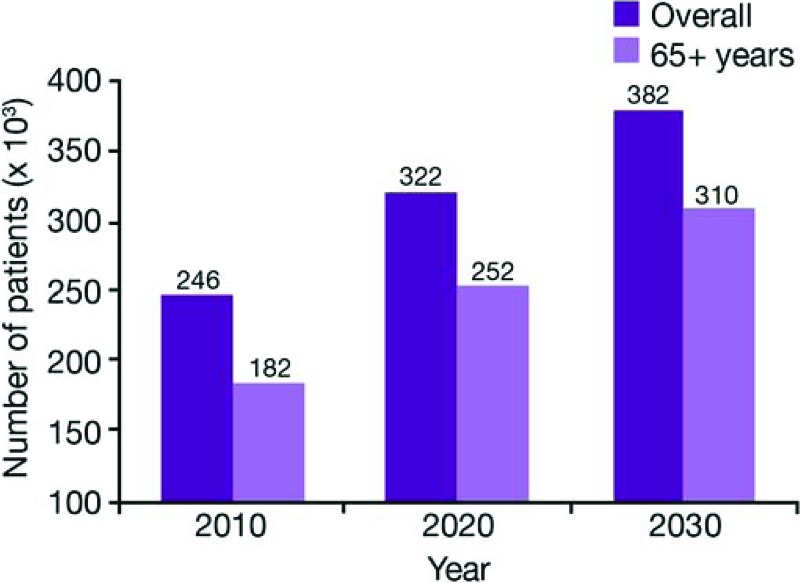

Life expectancy in the population as a whole is increasing [5], and we are seeing exponential aging worldwide. The number of people aged 80 years or older increased from 13.8 million in 1950 to 69.2 million in 2000, and a further increase to 379.0 million is forecast for 2050 [6]. Given this growth in the elderly population, the burden of prostate cancer is expected to worsen dramatically in the future. For example, it is anticipated that prostate cancer incidence in the U.S. will rise by 55% between 2010 and 2030, mainly driven by cancer diagnosis in older men, which is estimated to rise by 70% during the same period (Fig. 1) [7].

Figure 1.

Projected new cases of prostate cancer per year in the U.S. (2010–2030) [7].

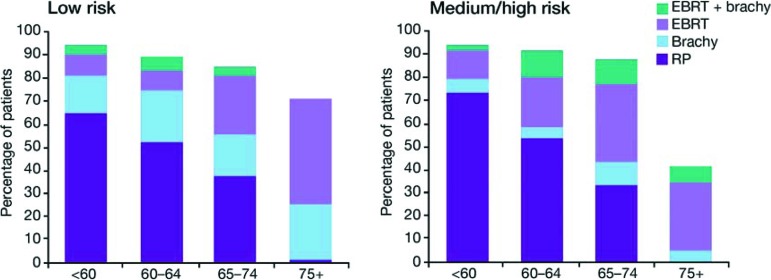

The management of senior adults with prostate cancer is not optimal. Only a minority of men over the age of 75 years with intermediate-risk or high-risk localized prostate cancer receive curative therapy (i.e., radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or brachytherapy), either in the U.S. (Fig. 2) [8] or in Europe [9].

Figure 2.

The age-specific percentage distribution of initial therapy by risk group [8].

Abbreviations: EBRT, external-beam radiotherapy; brachy, brachytherapy; RP, radical prostatectomy.

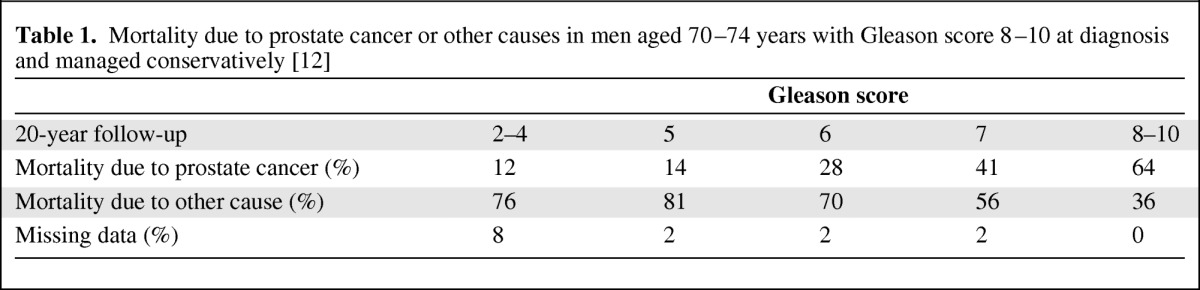

The low rate of curative therapy in senior adults is attributed to the assumption that these older men will die from other causes, not from prostate cancer. However, there is increasing evidence that men over the age of 70 years are more likely to have higher-risk prostate cancer—with higher clinical stage, Gleason score, and tumor volume—than younger men [10]. Without curative treatment, these aggressive tumors may lead to prostate cancer death in a significant number of men [11], which helps to explain the high rate of prostate cancer death at an advanced age. In a 20-year follow-up of a population-based cohort with localized prostate cancer between 1971 and 1984, men diagnosed after the age of 70 years of age with Gleason score 8–10 and managed conservatively (watchful waiting or androgen-deprivation therapy) had a 64% chance of dying of prostate cancer (Table 1) [12]. However, at an advanced stage of the disease, many oncologists are reluctant to give chemotherapy to prolong survival and improve patient's quality of life because of concerns over the tolerability.

Table 1.

Mortality due to prostate cancer or other causes in men aged 70–74 years with Gleason score 8–10 at diagnosis and managed conservatively [12]

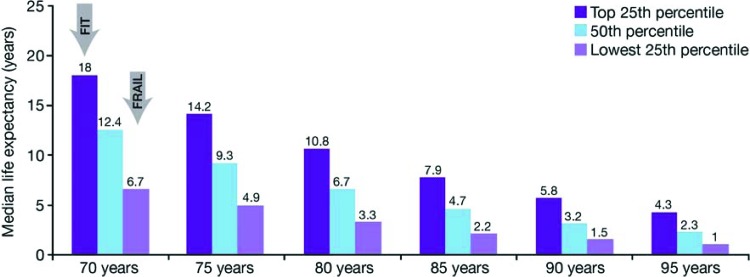

The challenge for the physician is to accurately evaluate the life expectancy of a given patient and balance the risk of dying due to prostate cancer (which depends on the Gleason score and tumor stage) with the risk of dying due to other causes. Life-expectancy estimates provided by Social Security Administration (SSA) tables apply only to populations, not to individuals. Life expectancy is highly variable from one individual to another, and this variability reflects differences in health status. For example, median life expectancy of a 70-year old man in the SSA tables is 12.4 years, but healthy individuals are expected to live for at least 18 years (upper quartile), whereas those with comorbid conditions will live for only 6.7 years (Fig. 3) [13].

Figure 3.

Life expectancy and health status in older men [13]. Adapted from Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750–2756, with permission.

Health status in senior adults mainly depends on the number and severity of comorbidities, and this relationship has been clearly established in localized prostate cancer [14]. The Charlson index, which rates exclusively potentially lethal comorbid conditions [15], has been identified as a much more powerful predictor of nonprostate cancer death than chronological age [16]. Complications of curative therapies such as radical prostatectomy [11, 17] and brachytherapy [18] are also more related to Charlson index than age. Nevertheless, both the functional and the nutritional status of the patient are also important parameters to consider in health status evaluation because the degree of dependence in daily living activities and malnutrition have been shown to significantly influence survival [19, 20].

The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) created a multidisciplinary Prostate Cancer Working Group to perform a systematic review of existing literature and establish recommendations for the management of senior adults with prostate cancer. The consensus of this task force is that senior men with prostate cancer should be managed according to their individual health status, which is mainly driven by the severity of associated comorbid conditions, not according to chronological age [14, 21]. Existing international recommendations [22–25] as well as national guidelines [26] form the backbone for the treatment of localized and advanced prostate cancer. However, it is important to supplement these recommendations with knowledge about the individual patient to determine which treatment strategy is most appropriate for that individual.

Best supportive care measures are also of primary importance to reduce the side effects of therapies and to optimize treatment outcomes, especially in senior adults who may be more affected by treatment complications compared with younger patients [21]. Quality of life is a key driver of treatment success at an advanced age, and it can be significantly improved by early detection and management of treatment side effects [14]. Therefore, active monitoring for any complications should be encouraged.

We can never stress enough the importance of multidisciplinary teams when deciding which treatment options to offer an individual patient. By bringing together surgeons, urologists, radiologists, social workers, and nurses, all of the available expertise can be combined, and varied aspects of individual patient care can be discussed in an evidence-based manner.

This supplement addresses all of these issues. The use of curative therapies—who should receive them and which treatment—is discussed by Heather Payne and Marcus Graefen. Matti Aapro details the emerging treatment opportunities for the management of advanced disease, and Florian Scotté presents his expertise in best supportive care to optimize the efficacy of therapies for senior adults with prostate cancer. The final article provides an overview of the SIOG recommendations for optimal management of prostate cancer in senior adults, which we hope will be useful in your daily practice.

This call to action aims to increase awareness of the growing burden of prostate cancer in senior adults and how improvements can be made to the way we currently treat many of these individuals. It is also a call to every country to systematically integrate training dedicated to senior adults in urology and oncology fellowship programs. Lastly, it is of primary importance that existing prostate cancer guidelines systematically integrate specific recommendations for the management of senior adults to optimize quality of care in this growing segment of the population.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writer Assistance: Assisted, Julie Knight, Succinct Healthcare Communications, provided copyediting/proofreading, editorial, and production assistance.

Footnotes

- (C/A)

- Consulting/advisory relationship

- (RF)

- Research funding

- (E)

- Employment

- (H)

- Honoraria received

- (OI)

- Ownership interests

- (IP)

- Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder

- (SAB)

- Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN 2008. Fast Stats: Estimated Age-Standardised Incidence and Mortality Rates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Prostate. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: preliminary data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population ageing: 1950–2050. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.un.org/

- 7.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton AS, Albertsen PC, Johnson TK, et al. Trends in the treatment of localized prostate cancer using supplemented cancer registry data. BJU Int. 2010;107:576–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houterman S, Jannsen-Heijnen MLG, Vereiji CD, et al. Greater influence of age than co-morbidity on primary treatments and complications of prostate cancer patients: An in-depth population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9:179–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L, Caire AA, Robertson CN, et al. Men older than 70 years have higher risk prostate cancer and poorer survival in the early and late prostate specific antigen eras. J Urol. 2009;182:2242–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez-Salas R, Prapotnich D, Rozer F, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy is feasible and effective in ‘fit’ senior adults with localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010;106:1530–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:2095–2101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285:2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, et al. Management of prostate cancer in older men: Recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int. 2010;106:462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tewari A, Johnson CC, Divine G, et al. Long-term survival probability in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: A case-control, propensity modelling study stratified by race, age, treatment and comorbidities. J Urol. 2004;171:1513–1519. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117975.40782.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1138–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen AB, D'Amico AV, Neville BA, et al. Patient and treatment factors associated with complications after prostate brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5298–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353:205–206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04402-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanc-Bisson C, Fonck M, Rainfray M. Undernutrition in elderly patients with cancer: target for diagnosis and intervention. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, et al. Background for the proposal of SIOG guidelines for the management of prostate cancer in senior adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:68–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Version 3.2012. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.nccn.org/

- 23.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. Guidelines on prostate cancer. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2012. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.uroweb.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59:572–583. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localised prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;177:2106–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prostate cancer: Diagnosis and treatment. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008. [Google Scholar]