This article discusses the importance of supportive care measures to optimize management and outcomes of older men with advanced prostate cancer.

Keywords: Supportive care, Side effects, Quality of life, Treatment outcomes

Abstract

Optimal oncologic care of older men with prostate cancer, including effective prevention and management of the disease and treatment side effects (so-called best supportive care measures) can prolong survival, improve quality of life, and reduce depressive symptoms. In addition, the proportion of treatment discontinuations can be reduced through early reporting and management of side effects. Pharmacologic care may be offered to manage the side effects of androgen-deprivation therapy and chemotherapy, which may include hot flashes, febrile neutropenia, fatigue, and diarrhea. Nonpharmacologic care (e.g., physical exercise, acupuncture, relaxation) has also been shown to benefit patients. At the Georges Pompidou European Hospital, the Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration has demonstrated that improved outpatient follow-up by supportive care measures can reduce the occurrence of chemotherapy-related side effects, reduce cancellations and modifications of treatment, reduce chemotherapy wastage, and reduce the length of stay in the outpatient unit. The importance of supportive care measures to optimize management and outcomes of older men with advanced prostate cancer should not be overlooked.

Introduction

The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) defines supportive care as “the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment” [1]. By reducing the effects of the disease and its treatment, supportive care contributes to improved patient quality of life, a reduction in therapy discontinuation for side effects, and hence optimization of outcomes [1]. Use of supportive care is of particular importance in senior adults, such as older men with prostate cancer, who may be especially vulnerable to treatment complications or side effects, especially when their health status is impaired as a result of concomitant comorbid conditions, functional losses, malnutrition, cognitive disorders, and geriatric syndromes [2].

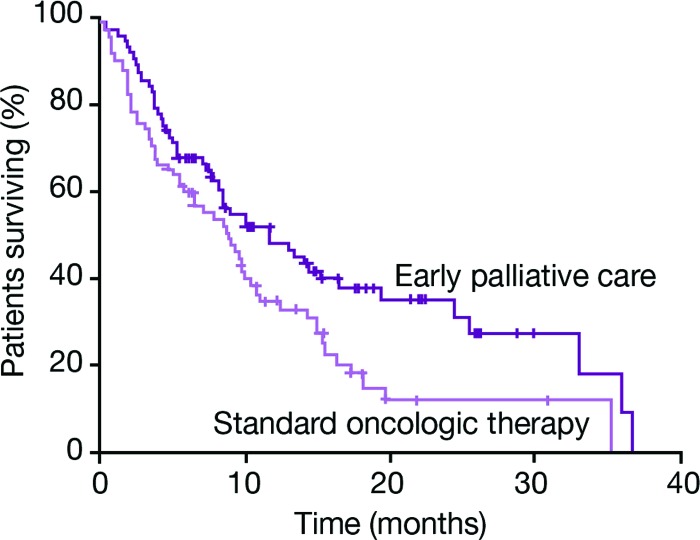

A randomized trial of standard oncologic therapy for second-line metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, administered with or without early palliative care, has demonstrated significantly longer survival (11.6 vs. 8.9 months; p = .02; Fig. 1), fewer depressive symptoms (16% vs. 38%; p = .01), and better quality of life (p = .03) in favor of early palliative care [3]. The early palliative measures were provided by a dedicated palliative care team consisting of board-certified palliative care physicians and advanced practice nurses, and included explanations to the patient about the disease and treatment goals, adequate symptom management (e.g., pain, pulmonary symptoms, fatigue, sleep disturbances and mood), assistance with treatment decision making, establishment of a care plan, and referral to other care providers. This scheme of early palliative care is close to the concept of supportive care defined by MASCC [1]. Interestingly, there was no difference between the groups in the total number of chemotherapy cycles delivered or the time to second-line or third-line chemotherapy administration, but there were significantly less intravenous chemotherapies administered shortly before death in the patients randomized to receive early palliative care [4].

Figure 1.

Early palliative care integrated into standard oncological therapy can prolong survival compared with standard oncologic therapy for second-line metastatic non-small cell lung cancer [3]. Adapted from Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742, with permission.

Supportive care for outpatients with advanced prostate cancer can be broadly divided into pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic measures. Pharmacologic supportive interventions in this setting include, for example, opioid or nonopioid analgesia for patients with painful bone metastases [5, 6], granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for grade ≥3 neutropenia [7], and, where required, antidiarrheals and treatments for depression [8, 9]. Nonpharmacologic measures include physical exercise, acupuncture, yoga, and dietary interventions [10]. Effective delivery of this multimodal approach to supportive care requires a multidisciplinary team (MDT; e.g., oncologist, specialist nurse, primary care providers, pain management team, palliative care expert, psychologist, spiritual care expert, dietician, social worker, kinesitherapist), with adequate communication and cooperation between different members of the care team.

Examples of Supportive Care Organization

The Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration at Georges Pompidou European Hospital

Optimal timing of the assessment of chemotherapy-related adverse events plays a pivotal role in effective supportive care. If this assessment is conducted on the treatment day itself, the patient may face a long wait and/or experience stress and the management of adverse events may be delayed. Furthermore, treatments may be modified, postponed, or cancelled on the day they were due to be administered, which can mean a wasted visit to the outpatient unit and a delay in treatment for the patient—all of which can have a negative impact on quality of life.

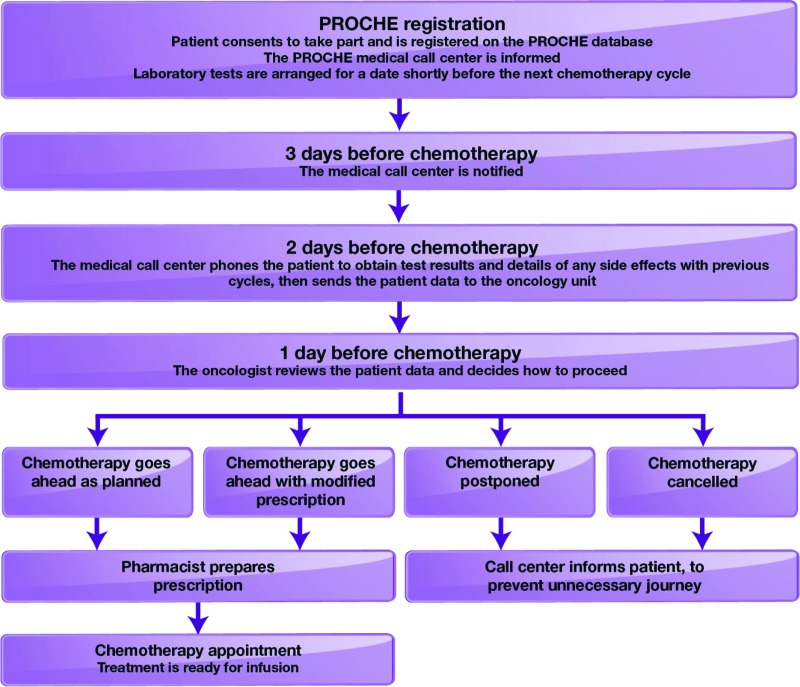

The Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration (PROCHE) was implemented at our institution, the Georges Pompidou European Hospital, to optimize the work of the chemotherapy outpatient unit, reduce unnecessary hospital stays, effectively manage adverse events, and improve patient quality of life and survival [11]. In PROCHE, a nurse-staffed call center acts as an intermediary between the MDT and the patient. Clinical and biological data are collected from the patient 2 days before chemotherapy is scheduled, allowing time for the MDT to review the data and make any necessary changes to the scheduled chemotherapy (e.g., dose modification, postponement, cancellation) prior to the patient's visit [11]. On the scheduled treatment day, the chemotherapy can be prepared in advance to be ready for the arrival of the patient, thereby minimizing waiting times (Fig. 2). Members of the supportive care team (e.g., psycho-oncologist, dietician, social worker) may also organize their time to suit each episode of patient care.

Figure 2.

Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration in practice [11].

Abbreviation: PROCHE, Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration.

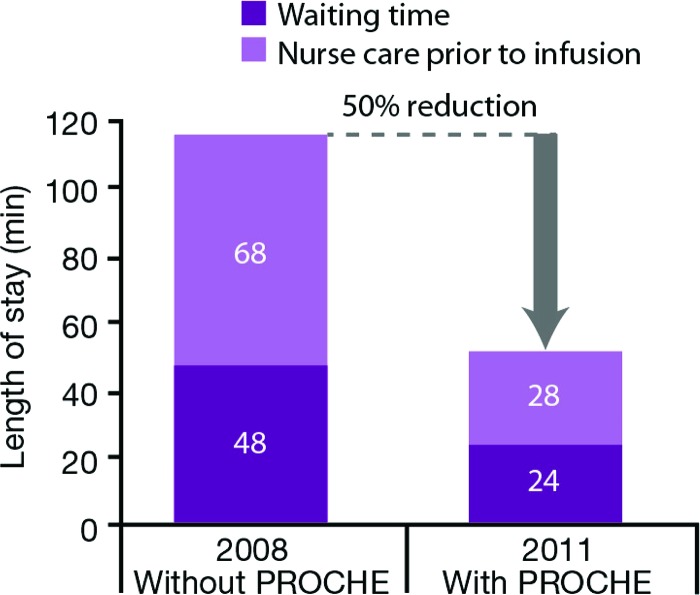

Use of PROCHE has been shown to reduce cancellations and modifications of treatment, reduce the wastage of chemotherapy preparations, and reduce the length of stay in the outpatient unit, allowing more patients to receive treatments each day (Fig. 3) [11]. A reduction in the median rate of modification or cancelation of chemotherapy as a result of inadequate side-effect management has also been shown.

Figure 3.

Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration reduces length of hospital stay [11].

Abbreviation: PROCHE, Program of Optimization of Chemotherapy Administration.

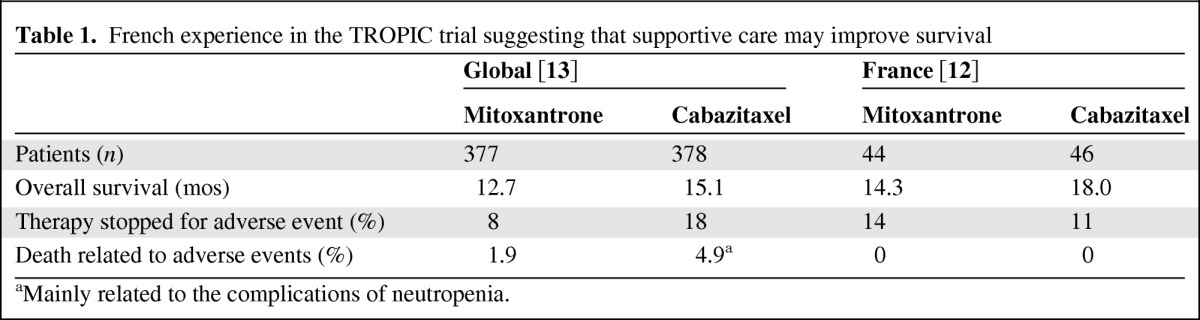

PROCHE was implemented for the majority of French patients participating in the phase III TROPIC trial of prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for advanced prostate cancer. Analysis of the trial results shows that, compared with global data, the cabazitaxel TROPIC arm in France was associated with fewer treatment discontinuations due to adverse events and improved survival benefit versus mitoxantrone, and there were no deaths related to adverse events (Table 1) [12, 13]. These data support the view that cabazitaxel plus best supportive care, including the early detection and management of treatment-related adverse events, may prolong survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer.

Table 1.

French experience in the TROPIC trial suggesting that supportive care may improve survival

aMainly related to the complications of neutropenia.

Other Initiatives and Tools to Evaluate Efficiency of Supportive Cancer Care

A study to improve waiting times for chemotherapy appointments at the Ambulatory Treatment Center (ATC) of the MD Anderson Cancer Center achieved a 26.8% reduction in mean patient waiting times compared with baseline times [14]. Excessive patient waiting time for chemotherapy was found to be a primary source of dissatisfaction among ATC patients. ATC staff members were frustrated by the frequency with which patients arrived physically on time but not ready for treatment. The study aimed to decrease mean patient waiting time from check-in to treatment by 25% in one of the six ATC outpatient units. Following a baseline assessment, a multifaceted plan to reduce overall patient waiting time was developed, incorporating three intervention strategies: increase appointment process efficiency within the ATC, enhance communications with relevant external centers and clinics, and employ an information technology-based communications application in the pharmacy. The interventions achieved a 15% decrease in the mean waiting time for prescheduled appointments (placeholder appointments without accompanying physician treatment orders) and a 29% decrease in mean waiting time for scheduled appointments.

Dynamic scheduling models have been developed to optimize chemotherapy outpatient scheduling and reduce waiting times [15–17]. Although the mathematical modeling of these templates suggests that they can offer improvements to chemotherapy scheduling, there is little evidence so far of their use in real-life practice.

Using specific search terms and selection criteria, Lorenz et al. assessed useful indicators for evaluating supportive cancer care [18]. Of the 133 proposed factors assessed by an expert panel, 92 were judged to be valid and feasible, 67 were identified as potentially useful for inpatient evaluation, and 81 were useful for outpatient evaluation: 26 address screening, 12 address diagnostic evaluations, 20 address management and 21 address follow-up. The final indicators form the Cancer Quality-ASSIST (Addressing Symptoms, Side Effects, and Indicators of Supportive Treatment) criteria to address each stage of illness and critical management; this set of ASSIST indicators can then be used to evaluate supportive care at the group-practice and health care system level, and, if necessary, to improve practice.

Telecare initiatives have shown positive results for improving outpatient palliative care. A U.K. study of telenursing in hospice palliative care addressed the issue of patient support after physician and home-health offices close, when the patient and their caregivers are left to cope alone [19]. Through an innovative partnership between B.C. Nurseline (a provincial teletriage and health information call center), the British Columbia Ministry of Health, and Fraser Health Hospice Palliative Care Program, access to an after-hours palliative care program was created for dying patients and their families. The program resulted in improved symptom management, decreased visits to emergency rooms and enhanced support for families caring for patients at home.

A review of telehealth in palliative care in the U.K. found that telehealth was being used by a range of health professionals in oncology care settings, including specialist palliative care, nursing homes and hospitals, hospices, primary care settings, and directly with patients and carers [20]. The applications used were most commonly out-of-hours telephone support, advice services, videoconferencing for interactive case discussions, and training and education of health care staff. Although the review determined that the current technology was acceptable to patients, it also found that there were challenges associated with integrating telehealth into routine practice.

In centers where these initiatives are not in place, it is vital that the supportive (or palliative) care team educate patients about the treatments they are receiving, any adverse events they may experience, and who to contact (and how) if they have any concerns out of working hours. Consequently, it is vital that the supportive care team have systems in place to ensure that any concerns or adverse events are promptly and appropriately managed when they are reported.

Pharmacologic Supportive Care in Advanced Prostate Cancer

In addition to the optimization of patient experience through optimization of scheduling processes and reducing patient waiting times and treatment cancellations, it is important to control the side effects associated with treatments such as chemotherapy and androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), which can impact patient quality of life.

Hot Flashes Due To Androgen-Deprivation Therapy

Hot flashes are considered to be the most common side effect of ADT, affecting patients receiving hormonal interventions for the treatment of prostate cancer and often persisting long term [21]. The time to onset after antihormone therapy varies from several days to several months, with an average of 2.7 months [22]. The frequency, duration, and intensity of hot flashes are very different depending on the individual—some patients may exceed 10 attacks per day—whereas duration, in most cases, is less than 3 minutes [23].

In the case of prostate cancer, hot flashes are experienced by up to 75% of patients [24] and can cause embarrassment and distress [25]. Hot flashes have a significant impact on quality of life [21] and treatments to reduce their frequency and severity can be beneficial to patients. Pharmacologic interventions for hot flashes include hormonal therapies. Estrogen-receptor modulators or low-dose estrogen have been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes, and there is also evidence for the efficacy of progesterone-based treatments [21]. Antidepressants such as venlafaxine, gabapentine, and pregabalin may also help to reduce hot flashes [23]. Nonpharmacologic interventions for hot flashes may also be used and are discussed later in this article.

Increased Risk of Fractures

The increased risk of fractures caused by ADT-associated reduction in bone density can be a major problem for older patients with advanced prostate cancer [2, 21, 26]. The prevention of osteoporosis is an important consideration; thus, the use of calcium supplementation and bisphosphonates, when indicated, is recommended [2, 8, 26]. Recently, results of a phase III trial showed that denosumab, a RANKL inhibitor, can also significantly reduce the cumulative incidence of new vertebral fractures in men receiving ADT for prostate cancer (of note, 83% were aged 70 years or older), as well as preventing loss of bone density [27].

Chemotherapy-Induced Febrile Neutropenia

It is known that older men will have a decreased bone marrow reserve, and this is likely to make them more prone to myelotoxicity and infections [28]. An increased risk of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia (defined by an absolute neutrophil count of <0.5 × 109/L plus fever or clinical signs of sepsis [29]) has been reported in older patients receiving chemotherapy for different tumor types, such as breast, lung, and hematologic malignancies [28]. The risk of severe neutropenia and febrile neutropenia in older men with advanced prostate cancer is less well documented, probably because of a lower incidence reported in randomized trials. In the Taxotere (TAX) 327 trial, the incidence of febrile neutropenia was 3% in men (median age, 68 years) with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) who were treated with docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) plus prednisone in the first-line setting [30]. A post-hoc analysis of TAX327 identified a higher rate (9%) of grade ≥3 infections with the docetaxel 3-weekly schedule in patients aged ≥75 years, compared with younger men (6% in men aged 65–75 and 3% in those under 65), but no detail regarding G-CSF use was provided [31].

At an even more advanced stage of prostate cancer, the novel taxane cabazitaxel, administered at a dose of 25 mg/m2 in men (median age, 68 years) whose disease progressed during or after docetaxel therapy, was associated with an incidence of febrile neutropenia of 8% [13]. In this trial which randomized 755 men with mCRPC to prednisone daily and either mitoxantrone or cabazitaxel every 3 weeks, primary prophylaxis with G-CSF significantly reduced the occurrence of neutropenia of grades ≥3 in both treatment arms, compared with later therapeutic use [32].

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) has published guidelines for the management of severe (grade ≥3) neutropenia, following an extensive review of the evidence [7]. The guidelines include an algorithm, based on evaluation of predisposing factors, to determine whether prophylactic G-CSF should be offered to the individual patient. The most important of these risk factors appears to be the age of the patient (≥65 years), but other parameters, such as advanced disease and prior episodes of febrile neutropenia, should also be considered. Evaluation of the need for G-CSF should be repeated at each treatment cycle. Similar recommendations have been issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [33] and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [34]. Although no specific trials have been carried out in mCRPC to investigate the use of G-CSF, special attention should be given to patient age, the extension of bone metastases, and prior radiotherapy/chemotherapy to evaluate the risk of febrile neutropenia.

Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea

In the TROPIC trial, diarrhea was the most common nonhematologic side effect observed with cabazitaxel [13]. It occurred mainly after the first cycle and was usually mild in severity (only 6% at grade ≥3). Nevertheless, it is important to manage this side effect as soon as it occurs to avoid dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, especially in older patients with advanced disease.

In the event of diarrhea, the patient should drink 8–10 large glasses of fluid to avoid dehydration, eat frequent small meals (e.g., bananas, rice, applesauce, toast), and stop all lactose-containing products and alcohol [35]. Diarrhea at grade 1 (increase of four stools per day over baseline) or grade 2 (increase of 4–6 stools per day over baseline) can be managed at home with oral loperamide (4 mg following the first episode, then 2 mg every 4 hours or 2 mg after each episode). If this intervention has no effect after 48 hours, subcutaneous octreotide can be prescribed at a dose of 100–500 μg every 8 hours. Patients with grade ≥3 diarrhea should be admitted to hospital for intravenous rehydration. Subcutaneous octreotide should be initiated at a dose of 100–500 μg every 8 hours, and the dose should be increased until it becomes effective.

Nonpharmacologic Supportive Care in Advanced Prostate Cancer

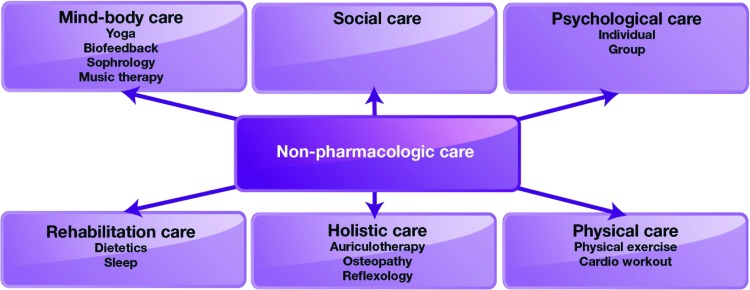

The nonpharmacologic approach to side-effect management is also of crucial importance. It includes social and psychological care, mind-body care (e.g., yoga, biofeedback, sophrology, music therapy), holistic care (auriculotherapy, osteopathy, reflexology), rehabilitation care (which may focus on sleep and dietetics), and physical care, including physical exercise and cardiovascular workout (Fig. 4) [10, 36].

Figure 4.

Nonpharmacologic supportive care used in patients with cancer [10, 36].

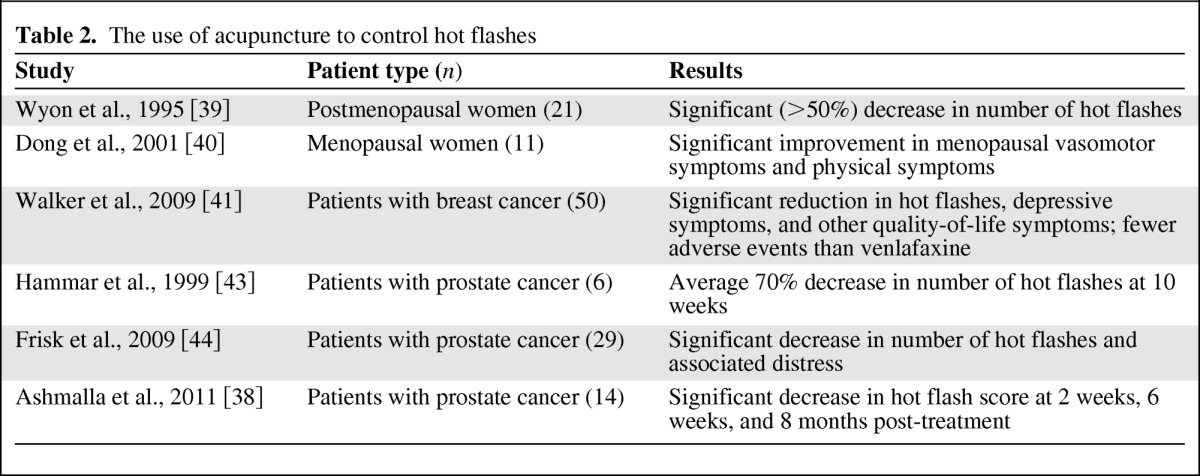

Acupuncture

Hot flashes are common and disabling in patients treated for prostate cancer [24, 25]. Indeed, the side effects of chemotherapy and androgen blockade include hot flashes and, for medical reasons, management with hormone replacement therapy is inappropriate. Quality of life of these patients is impaired, which can cause them to limit or stop their treatment, and survival may be reduced as a result of incomplete treatment.

Difficulties related to the psychotropic treatments frequently used in this indication led to some complementary medicines being evaluated. Acupuncture is one of these complementary therapies; it has shown some efficacy in the treatment of various cancer symptoms, such as neuropathic pain [37]. The mechanism of acupuncture analgesia has been attributed to the release of beta endorphins and serotonin. This release may be of benefit in hot flashes since decreased levels of beta endorphins and serotonin secondary to hormone deprivation may induce central thermoregulation instability [38].

Several promising studies have evaluated the effectiveness of this technique for hot flashes. Two pilot studies showed a reduction of about 50% in vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with 5–8 weeks treatment [39, 40].

In the study by Walker et al. in patients with breast cancer, acupuncture showed comparable efficacy to venlafaxine, which is considered to be the standard treatment for hot flashes [41]. In addition to the efficacy during treatment, there was an extension of benefits for up to 2 weeks from the end of treatment in the acupuncture arm, contrary to the arm treated with venlafaxine. Furthermore, patients treated with acupuncture had no adverse effects, compared with 18 different effects recorded in the reference arm. This technique also seems promising as part of the treatment of prostate cancer patients receiving antihormone therapy because small pilot trials have reported reductions in hot flashes ranging from 70% to 89% over a 6- to 8-month follow-up period, with no adverse effects [38, 42–44].

One pilot study of seven men with prostate cancer offered patients traditional acupuncture twice weekly for 2 weeks and then once a week for 10 weeks [43]. When assessed at 10 weeks, a 70% average reduction in the number of hot flashes was observed. Three months after the last treatment, the number of flashes was 50% lower than before therapy. A multicenter study compared traditional acupuncture with electrostimulated acupuncture in 31 men with hot flashes due to prostate cancer [44]. Hot flashes per 24 hours decreased significantly in both treatment groups (p = .012 for the electrostimulated group and p = .001 with traditional acupuncture). The distress caused by hot flashes also decreased significantly in both groups (p = .003 with electrostimulated and p = .001 with traditional acupuncture). These studies are summarized in Table 2 [38–41, 43–44]. Large randomized placebo-controlled trials are warranted to confirm the results seen in these pilot studies.

Table 2.

The use of acupuncture to control hot flashes

Frozen Gloves and Socks To Prevent Chemotherapy Nail and Skin Toxicity

Nail changes (including hyperpigmentation, splinter hemorrhage, subungual hematoma, subungual hyperkeratosis, orange discoloration, onycholysis) and skin toxicity (erythema and desquamation of the skin of the extremities) have been reported in about 30% of patients treated with docetaxel [45, 46]. It affects patient quality of life and limits the doses of chemotherapy that can be administered. It can be prevented through the use of frozen gloves and socks during each docetaxel infusion [45, 46].

Physical Exercise

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials has shown that exercise can offer many benefits to patients with cancer [47]. Improvements have been recorded in quality of life, psychological wellbeing, physical strength, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, pain, depression, anxiety, and sleeping problems [47, 48]. In prostate cancer, men walking 90 minutes per week at a normal to very brisk pace had a 46% lower risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.41–0.71) compared with shorter durations at an easy walking pace, according to the health professionals follow-up study [49]. In this study, it was also suggested that a modest amount of vigorous activity, such as cycling, tennis, jogging or swimming, for at least 3 hours per week, could substantially improve prostate-cancer-specific survival by 61% (HR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.18–0.84; p = .03) and reduce all-cause mortality by 49% (HR: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.36–0.72).

Yoga

Yoga involves physical postures that develop strength and flexibility to promote relaxation. It is also a meditative practice because the practitioner focuses on the body and breath in each pose [50]. As a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), yoga is often criticized in the literature due to the lack of large randomized trials. For example, a review by Sood et al. found that there was insufficient data to recommend any specific CAM modality for cancer-related fatigue [51]. Therefore, the authors proposed that potentially effective CAM interventions (e.g., acupuncture, massage) should be further studied in large randomized clinical trials and that other interventions should be tested in well-designed feasibility and phase II trials.

However, some research has shown that improvements in patient quality of life can be achieved with yoga. Lorenzo Cohen, a physician involved with CAM, reported data on the efficacy of yoga in lymphoma and breast cancer during radiotherapy [52, 53]. In patients with lymphoma, there was a significant improvement in sleep-related outcomes in the yoga group compared with the wait-list control group [52]. General health perception and physical-functioning scores were significantly better in patients with breast cancer who were randomized to the yoga group compared with the wait-list control group [53].

Bower et al. also demonstrated the impact of this intervention among breast cancer survivors [50]. In this small randomized study comparing 12-week Iyengar-based yoga with health education (control), there was a significant improvement in fatigue and vigor with yoga. This difference persisted over a 3-month follow-up. Despite high levels of fatigue at study initiation, adherence to yoga intervention was excellent, with over 80% of participants attending at least 20 of the 24 yoga classes offered. Both groups also had positive changes in depressive symptoms and perceived stress (p < .05), but no significant changes in sleep or physical performance were observed.

A small feasibility study of yoga for prostate cancer survivors involved a 7-week class-based course of yoga, followed by 7 weeks of self-selected physical activity [54]. Among the 15 prostate cancer survivors taking part, average class attendance was 6.1 of the 7 classes. Significant improvements in stress, fatigue and mood (all p < .05) before and after yoga classes were reported by all participants.

Larger randomized trials of yoga, as well as other CAMs, should be developed in prostate cancer and other advanced diseases to further investigate the potential improvements to patient quality of life.

Conclusion

Overall, a combined pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approach to supportive care in advanced prostate cancer should be used to reduce treatment side effects, improve patient quality of life, and maximize the efficacy of therapies through avoidance of dose reductions and treatment discontinuations. A randomized controlled trial is currently recruiting in New Zealand to compare standard medical management plus evidence-based patient education to multimodal supportive care intervention for men recently diagnosed with localized prostate cancer [55]. In comparison to standard medical care and evidence-based patient education, the multimodal supportive care will involve self-management and a telebased peer support group (teleconferences facilitated by a nurse counselor and an experienced trained peer). The supportive care arm will aim to identify target areas for improvement, evaluate prime concerns, and set self-management goals as well as setting low-cost and easily implemented exercise goals. A similar approach is needed for advanced prostate cancer to further document the benefit of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, such as acupuncture and yoga, in terms of patient quality of life and improvement of psychological distress.

Programs such as PROCHE at the Georges Pompidou European Hospital have the potential to improve treatment outcomes through closer monitoring of patients between planned hospital visits. These programs should be further investigated with evaluation of results in the longer term, optimization of call frequency, and progressive extension to patients receiving oral chemotherapy. A best supportive care MDT with specialists in each area of side-effect management should be formed to oversee different aspects of patient care and thereby improve treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writer Assistance: Assisted, Julie Knight, Succinct Healthcare Communications, provided copyediting/proofreading, editorial, and production assistance.

References

- 1.Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. Welcome to MASCC. Hillerød, Denmark: Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, et al. Background for the proposal of SIOG guidelines for the management of prostate cancer in senior adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:68–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30:394–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akakura K, Akimoto S, Shimazaki J. Pain caused by bone metastasis in endocrine-therapy-refractory prostate cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122:633–637. doi: 10.1007/BF01221197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Adult cancer pain. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Version 1.2012. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf.

- 7.Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, et al. 2010 update of EORTC guidelines for the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients with lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:8–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Prostate cancer. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Version 3.2012. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf.

- 9.Esper P, Redman BG. Supportive care, pain management, and quality of life in advanced prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:375–389. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassileth BR, Gubili J, Yeung KS. Integrative medicine: Complementary therapies and supplements. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6:228–233. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scotté F, Berhoune M, Marsan S, et al. PROCHE: A program to monitor side effects among patients treated in a medical oncology outpatient unit. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl):9152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouessel D, Oudard S, Gravis G, et al. Cabazitaxel for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: The TROPIC study in France. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:731–741. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2012.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kallen MA, Terrell JA, Lewis-Patterson P, et al. Improving wait time for chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Prac. 2012;8:e1–e7. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg B, Denton BT, Erdogan SA, et al. Optimal booking strategies for outpatient procedure centers. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.ise.ncsu.edu/bdenton/Papers/pdf/Berg-2011.pdf.

- 16.Hahn-Goldberg S, Carter MW, Beck JC. Dynamic template scheduling to address uncertainty in complex scheduling problems: a case study on chemotherapy outpatient scheduling. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.iienet2.org/uploadedfiles/SHSNew/Hahn-GoldbergS_paper_SHS2012_Grad.pdf.

- 17.Turkan A, Zeng B, Lawley M. Chemotherapy operations planning and scheduling. 2011. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Available at http://www.optimization-online.org/DB_FILE/2010/02/2543.pdf.

- 18.Lorenz KA, Dy SM, Naeim A, et al. Quality measures for supportive cancer care: The Cancer Quality-ASSIST Project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:943–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts D, Tayler C, MacCormack D, et al. Telenursing in hospice palliative care. Can Nurse. 2007;103:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidd L, Cayless S, Johnston B, et al. Telehealth in palliative care in the UK: A review of the evidence. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:394–402. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al. Guidelines on prostate cancer. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charig CR, Rundle JS. Flushing. Long-term side effect of orchiectomy in treatment of prostatic carcinoma. Urology. 1989;33:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(89)90385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loprinzi CL, Qin R, Balcueva EP, et al. Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of pregablin for alleviating hot flashes, N07C1. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:641–647. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow PKH, Mattair DN, Hortobagyi GN. Hot flashes: A review of pathophysiology and treatment modalities. The Oncologist. 2011;16:1658–1664. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barton D, Loprinzi CL. Making sense of the evidence regarding nonhormonal treatments for hot flashes. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:39–42. doi: 10.1188/04.CJON.39-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Droz J-P, Balducci L, Bolla M, et al. Management of prostate cancer in older men: Recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int. 2010;106:462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernández Toriz N, et al. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:745–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallis AG, Fortpied C, Wedding U, et al. EORTC elderly task force position paper: Approach to the older cancer patient. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1502–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford J, Caserta C, Roila F. Hematopoietic growth factors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for the applications. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v248–v251. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seruga B, Horgan AM, Pond GR, et al. Tolerability and efficacy of chemotherapy in older men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) in the TAX 327 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.12.001. Abstract 4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozguroglu M, Oudard S, Sartor AO, et al. Effect of G-CSF prophylaxis on the occurrence of neutropenia in men receiving cabazitaxel plus prednisone for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) in the TROPIC study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7 suppl) Abstract 144. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Senior adult oncology. [Accessed June 1, 2012]. Version 2.2012. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/senior.pdf.

- 34.Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3187–3205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien BE, Kaklamani VG, Benson AB. The assessment and management of cancer treatment-related diarrhea. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2005;4:375–381. doi: 10.3816/ccc.2005.n.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavares M. National guidelines for the use of complementary therapies in supportive and palliative care. Cardiff, London: The Prince of Wales's Foundation for Integrated Health and the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassileth BR, Keefe FJ. Integrative and behavorial approaches to the treatment of cancer-related neuropathic pain. The Oncologist. 2010;15:19–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashamalla H, Jiang ML, Guirguis A, et al. Acupuncture for the alleviation of hot flashes in men treated with androgen ablation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1358–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wyon Y, Lindgren R, Lundeberg T, et al. Effects of acupuncture on climacteric vasomotor symptoms, quality of life, and urinary excretion of neuropeptides among postmenopausal women. Menopause. 1995;2:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong H, Ludicke F, Comte I, et al. An exploratory pilot study of acupuncture on the quality of life and reproductive hormone secretion in menopausal women. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:651–658. doi: 10.1089/10755530152755207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker E, Rodriguez A, Kohn B, et al. Acupuncture versus venlafaxine for the management of vasomotor symptoms in patients with hormone receptor positive breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28:634–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenner A. Prostate cancer: Acupuncture can alleviate hot flashes in prostate cancer patients. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:530. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammar M, Frisk J, Grimås O, et al. Acupuncture treatment of vasomotor symptoms in men with prostatic carcinoma: A pilot study. J Urol. 1999;161:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frisk J, Spetz AC, Hjertberg H, et al. Two modes of acupuncture as a treatment for hot flushes in men with prostate cancer—A prospective multicenter study with long-term follow-up. Eur Urol. 2009;55:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scotté F, Tourani JM, Banu E, et al. Multicenter study of a frozen glove to prevent docetaxel-induced onycholysis and cutaneous toxicity of the hand. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4424–4429. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.15.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scotté F, Banu E, Medioni J, et al. Matched case-control phase 2 study to evaluate the use of a frozen sock to prevent docetaxel-induced onycholysis and cutaneous toxicity of the foot. Cancer. 2008;112:1625–1631. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knols R, Aaronson NK, Uebelhart D, et al. Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: A systematic review of randomised and controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3830–3842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults (review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD006145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, et al. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the health professionals follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:726–732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Results of a pilot study. Cancer. 2012;118:3766–3775. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sood A, Barton DL, Bauer BA, et al. A critical review of complementary therapies for cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534735406298143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, et al. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2253–2260. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8:43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ross Zahavich AN, Robinson JA, Paskevich D, et al. Examining a therapeutic yoga program for prostate cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012 Jun 27; doi: 10.1177/1534735412446862. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chambers SK, Newton RU, Girgis A, et al. Living with prostate cancer: Randomised controlled trial of a multimodal supportive care intervention for men with prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]