Abstract

Membrane protein manipulation is a challenging task owing to limited tertiary and quaternary structural stability once the protein has been removed from a lipid bilayer. Such instability can be overcome by embedding membrane proteins in detergent micelles formed from amphiphiles with carefully tuned properties. This study introduces a class of easy-to-synthesize amphiphiles, which are designated CGT (Chae’s Glyco-Triton) detergents. Some of the agents are well suited for membrane protein solubilization and stabilization.

Integral membrane proteins reside in lipid bilayers and play central roles in a variety of cellular processes including nutrient exchange, signal transduction, and cell-to-cell communication. The fact that more than half of all pharmaceutical agents in development target membrane proteins underlines the importance of these bio-macromolecules’ roles in normal and disease states of cells.1 Despite the tremendous efforts, however, the set of membrane proteins with known structure is far smaller than the set of soluble proteins for which high-resolution structures are available. This difference is mainly due to the inherent physical properties of membrane proteins, which makes them difficult to manipulate.2 Detergents serve as indispensable tools in membrane protein experiments. These amphipathic molecules self-assemble to form micelles that interact with the hydrophobic portions of membrane proteins in an aqueous medium. The resulting protein detergent complexes (PDCs) are water-soluble because the hydrophobic patches of proteins are effectively shielded by detergent molecules.3

Successful membrane protein ‘solubilization’ is a requirement for the multi-step process that leads to structural information on these difficult targets. A large number of conventional detergents are available, but only a small number are widely used in membrane protein manipulation, including OG (n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside), DDM (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) and LDAO (lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide). However, even membrane proteins solubilized with these popular agents are prone to aggregation and denaturation.4 This protein instability in detergent micelles can originate from various factors, including the absence of the lateral pressure characteristic of a native lipid bilayer, the absence of specific interactions of lipid molecules with the protein, and micelle inhomogeneity. Therefore, novel classes of amphiphiles that have ability to preserve native structure are of great importance for the future success of membrane protein research.

Several types of amphiphilic molecules have been devised to circumvent the limitations of conventional detergents.5 Examples include tripod amphiphiles (TPAs)5a,b, amphiphilic polymers (amphipols)5c,d hemifluorinated surfactants (HFSs)5e,f, nanodiscs5d,g, rigid hydrophobic group-bearing amphiphiles5h–l and amphipathic peptides5n–o. We recently developed maltose-neopentyl glycol (MNG) amphiphiles, which have enabled the growth of high-quality crystals of several GPCRs via the lipidic cubic phase (LCP) system6a–h, and glucose-neopentyl glycol (GNG) amphiphiles, which have facilitated the crystal structure determination of a sodium-pumping phosphatase.7a,b These successful examples indicate the pivotal roles that novel agents can play in membrane protein studies. It is, however, unlikely that any single detergent will be a 'magic bullet' for all membrane proteins. The number of currently useful tools and the scope of their utility are seriously limited, hampering the advance of membrane protein research.

Most studies of new amphiphiles over the past few decades have focused on the stabilization of membrane proteins after they have been extracted from the native bilayer, with little information on the abilities of such amphiphiles to solubilize proteins from the membrane-embedded state. It is noteworthy that popular detergents for membrane protein crystallization (e.g. DDM, OG and LDAO) are often also effective for protein solubilization from the native membrane. Thus, we seek new amphiphiles that are effective both at extracting membrane proteins from the bilayer and at maintaining the extracted protein in a stable form.

Triton X-100 (TX-100) is a nonionic detergent with a polyethylene oxide chain as a hydrophilic group and an aromatic hydrocarbon with a branched alkyl substituent as a hydrophobic group. This agent is widely used in a number of commercial and industrial products such as detergents, emulsifiers, solubilizers, dispersing and wetting agents.8a,b Such wide use originates from its excellent ability to solubilize various entities with the hydrophobic surfaces including membrane proteins,9a,b carbon nanotube,9c–e influenza vaccine,9f liposomes,9g and native membranes.9h Its hydrogenated analogue of TX-100, which does not absorb light in the 280 nm region, has also been used in biochemical studies.10a,b TX-100 is heterogeneous due to the variable length of oligo-ethylene oxide unit (on average 9.5), which may be unfavorable for membrane protein studies, particularly crystallogenesis experiments. Polyethylene oxide-bearing agents such as TX-100 and Brij 35 are sensitive to oxidation11a–d, thereby necessitating careful storage.

On the other hand, carbohydrate-containing detergents such as alkyl glucosides and maltosides are chemically homogeneous and stable relative to oxidation. Furthermore, carbohydrate-containing detergents have proven to be mild relative to polyethylene oxide-bearing counterparts in terms of avoiding the disruption of native membrane protein structure, making the former widely used for membrane protein research.12a,b These considerations led us to synthesize and evaluate glucose- or maltose-containing TX-100 analogues. We show that these new amphiphiles are favorable for solubilization and stabilization of large, multi-subunit membrane protein assemblies containing components that are fragile once removed from a lipid bilayer.

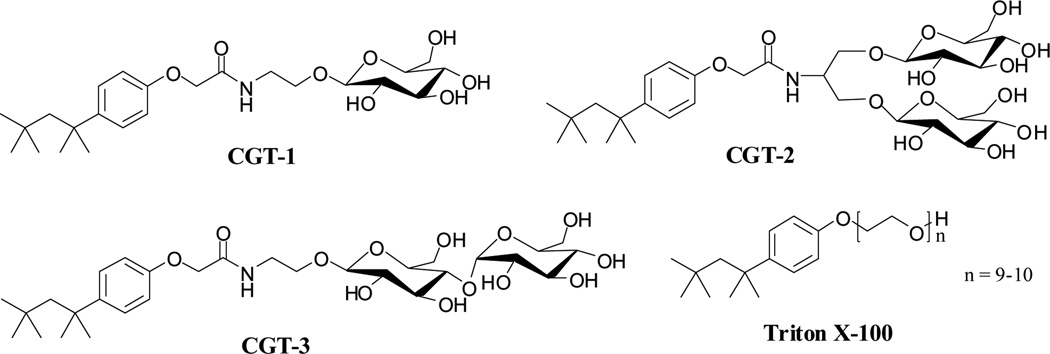

The new analogues of TX-100 we developed are designated CGT-1, CGT-2 and CGT-3 in Fig 1. Each CGT detergent contains the hydrophobic unit found in TX-100, but the hydrophilic unit is based on a carbohydrate: glucose in CGT-1, branched diglucoside in CGT-2, or maltose in CGT-3. The branched diglucoside was introduced because this headgroup displayed favorable behavior for membrane protein stabilization in a previous study, which focused on a different type of hydrophobic unit.5b Carbohydrate units were connected to the hydrophobic moiety by using 2-ethanolamine (CGT-1 and CGT-3) or serinol (CGT-2) as a linker. All CGT compounds were prepared via straightforward chemical reactions (3 steps) and in high overall yields (> 85%) (see supporting information for details). This route is amenable to multi-gram-scale synthesis.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of new amphiphiles (CGT-1, CGT-2 and CGT-3) and conventional Triton X-100.

CGT-1, containing only one glucose unit, was not soluble in aqueous media and was not characterized further. The other two agents, CGT-2 and CGT-3, were highly soluble (> 20 wt %). Solubilization experiments employing a hydrophobic UV-absorbing dye, orange OT13, were used to determine critical micelle concentrations (CMC) for these new detergents, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) allowed us to estimate the hydrodynamic radii (Rh) of the micelles. The data for CGT-2 and CGT-3, previously described TPAs (TPA-2 and TPA-4; Fig S1) and three conventional detergents (DDM, TX-10014a and LDAO14b) are presented in Table 1. The CMC values of CGT-2 and CGT-3 were around 10 times larger than those of DDM and TX-100, and comparable to that of LDAO in terms of molarity. The micelles formed by CGT-2 are smaller than those formed by DDM or TX-100, while the micelles formed by CGT-3 are substantially larger than those formed by DDM or TX-100. This difference is consistent with the general notion that the relative size of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic groups (i.e., molecular geometry) has a substantial impact on self-association behavior.15 The two CGT agents, CGT-2 and CGT-3, each showed one set of micelle distributions, as does TX-10014a in the DLS experiments (Fig S2).

Table 1.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC), hydrodynamic radii (Rh) of the micelles (mean ± SD, n = 5) and protein solubilization yields for CGT amphiphiles (CGT-2 and CGT-3), previously described TPAs (TPA-2 and TPA-4) and three conventional detergents (DDM, TX-100 and LDAO).

| MWa | CMC (mM) |

CMC (wt %) |

Rh (nm)b | SY (%)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGT-2 | 661.7 | ~2.6 | ~0.17 | 2.6 ± 0.10 | ~30 |

| CGT-3 | 631.7 | ~1.9 | ~0.12 | 5.4 ± 0.09 | ~85 |

| TPA-2 | 659.8 | ~3.6 | ~0.24 | 2.0 ± 0.06 | ~50 |

| TPA-4 | 629.7 | ~4.0 | ~0.25 | N.D. | ~95 |

| DDM | 510.1 | ~0.17 | ~0.0087 | 3.5 ± 0.04 | ~70 |

| TX-100 | ~625 | ~0.22 | ~0.01 | 4.2d | > 95 |

| LDAO | 229.4 | 1-2 | ~0.023 | 2.0d | ~100 |

Molecular weight of detergents.

Hydrodynamic radius of micelles as determined at 0.5 wt %. TPA-2 was used at 1.0 wt % to obtain strong signal.

Solubilization yield of R. capsulatus photosynthetic superassembly from the native intracytoplasmic membranes.

These values were obtained from the literatures.14

N.D. = Not Determined.

In order to evaluate the new detergents as biochemical tools, we utilized the photosynthetic superassembly of Rhodobacter (R.) capsulatus. The multi-subunit, pigment-protein complex is comprised of the very labile light harvesting complex I (LHI) and the more resilient reaction center complex (RC); the robust light harvesting complex II was genetically deleted.16 The photosynthetic superassembly is an intricate supra-molecular machine that functions to carry out a sequential series of light-harvesting and electron-transfer reactions. These complexes from purple, non-sulfur bacteria served as early models for analogous systems found in higher plants. The detailed understanding of the early events of excited-state energy transfer and charge separation in photosynthesis were enabled by the ability to study the structure and function of these complexes in vitro – most commonly solubilized and stabilized by detergent micelles.

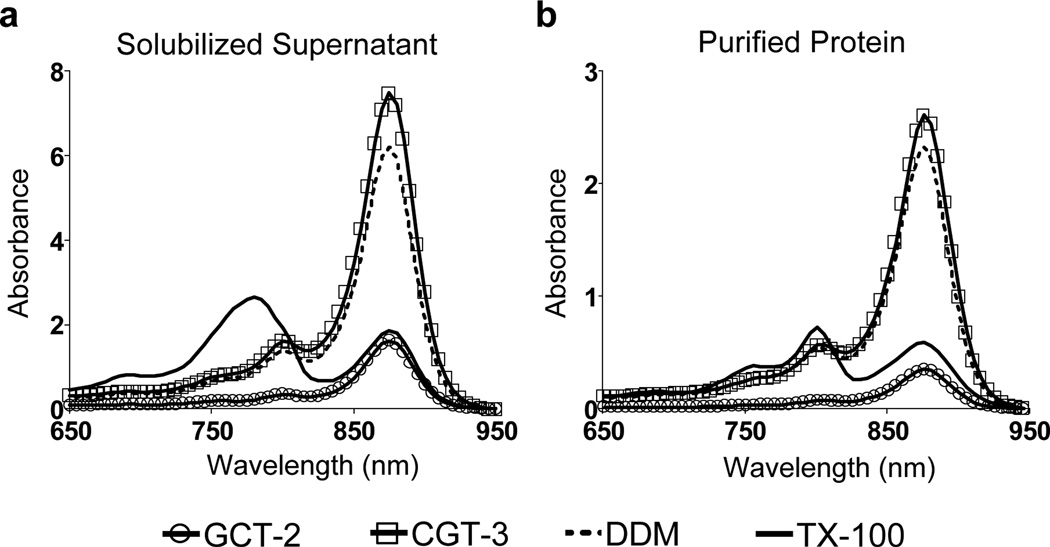

The LHI-RC complex contains 30–40 protein molecules from 5 different components, rendering it challenging to maintain the native quaternary structure. This complex includes various types of cofactors such as bacteriochlorophyll and bacteriopheophytin, giving rise to a highly structured UV-Visible spectrum. We used the absorption spectrum of the complex to evaluate detergent efficacy for protein stabilization.5b The prominent absorbance peak at 875 nm indicates the structural integrity of LHI-RC complex while, alternatively, strong absorbance at ~800 nm and ~760 nm represent the intact RC but denatured LHI, or denatured LHI and RC, respectively. Thus, such characteristic absorption spectra allowed us to determine solubilization and stabilization propensities of the newly-synthesized detergents via convenient optical spectrophotometry. In a previous study, we found that DDM was one of the best among conventional detergents for the stabilization and solubilization of the LHI-RC complex,5b which is consistent with the extensive use of the agent in membrane protein research.17 We included DDM, LDAO and TX-100 as control agents for the present comparative study.

The assay began by the treatment of intracytoplasmic R. capsulatus membranes enriched in LHI-RC complexes with 1.0 wt % each agent for the protein solubilization. The cellular debris was then removed via ultracentrifugation. The spectra of the resulting supernatant and resuspended pellet following solubilization were used to quantify the fraction of superassembly that was solubilized and to assess the stability of the LHI-RC complex in the micelles of the detergent employed. As can be seen in Fig 2a, TX-100-solubilized protein underwent significant structure degradation (intact RC but denatured LHI), although TX-100 extracted most of the complex (> 95%; Fig S3 & Table 1); only a small peak at 875 nm was remained for the solubilized sample. On the other hand, CGT-2, with a branched diglucoside headgroup, was not efficient at solubilizing the LHI-RC complex (~30%), b ut this new detergent appeared to be effective at maintaining native structure for the fraction of complex that was solubilized. The maltose-containing analogue, CGT-3, displayed the most favorable balance: the LHI-RC solubilization efficiency was excellent (~85%; vs. ~70% with DDM), and native structure of the solubilized LHI-RC complex was maintained as effectively as with DDM.

Figure 2.

Spectra of R. capsulatus superassembly (a) solubilized and (b) purified in individual detergents. Detergents were used at 1.0 wt % for the protein solubilization and at 1xCMC for protein purification. The superassembly was purified via Ni-NTA affinity column.

Solubilized protein was subjected to immobilized metal affinity chromatography for initial purification with the binding of the entire complex facilitated by a seven-membered histidine tag on the C-terminus of the M-subunit of the RC; each detergent was used at its CMC. The spectra of the purified proteins in individual detergents showed a trend similar to that seen before purification (Fig 2 & Fig S4). TX-100 destroyed most of the LHI, but RC remained intact. LDAO displayed similar behavior (Fig S4). CGT-3 preserved the native structure of LHI-RC complex as effectively as DDM during the course of purification.

In summary, we have described new carbohydrate-containing TX-100 analogues, which are designated CGT detergents, and provided a preliminary assessment of their utility as tools for membrane protein manipulation. The quaternary stability of a photosynthetic reaction center superassembly was significantly enhanced for analogues bearing diglucoside or maltoside headgroup, relative to TX-100 itself. The best new detergent, CGT-3, was more effective than conventional detergents (DDM and LDAO) as well as previously reported TPAs5b, TPA-2 and TPA-4, in solubilization efficiency and stabilization efficacy. It is interesting to note that maltose-containing amphiphiles such as TPA-4 and CGT-3 outperformed diglucose-containing amphiphiles such as TPA-2 and CGT-2 in terms of disrupting lipid bilayers and solubilizing superassemblies from the membrane. More molecule sets are needed with analogous comparisons in the future whether the relative merits of these two hydrophilic groups are universal in the context of membrane protein manipulation. Our data raise the possibility that CGT-3 will prove to be a useful biochemical research tool because of its ease of synthesis and its efficacy in membrane protein solubilization and stabilization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant number 2008-0061856 and 2012R1A1A1040964 to P.S.C., K.H.C.), and NIH grant P01 GM75913 (S.H.G., P.D.L., M.J.W).

Footnotes

† Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental detail of the amphiphiles’ synthesis and their evalution for membrane proteins.

Contributor Information

Pil Seok Chae, Email: pchae@hanyang.ac.kr.

Philip D. Laible, Email: laible@anl.gov.

Samuel H. Gellman, Email: gellman@chem.wisc.edu.

Notes and references

- 1.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacapere JJ, Pebay-Peyroula E, Neumann JM, Etchebest C. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) White SH, Wimley WC. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moller JV, le Maire J. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18659–18672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:32403–32406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bowie JU. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Serrano-Vega MJ, Magnani F, Shibata Y, Tate CG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:877–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711253105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) McQuade DT, Quinn MA, Yu SM, Polans AS, Krebs MP, Gellman SH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:758–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chae PS, Wander MJ, Bowling AP, Laible PD, Gellman SH. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1706–1709. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot J-L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:15047–15050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Popot J-L, et al. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2011;40:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Breyton C, Chabaud E, Chaudier Y, Pucci B, Popot J-L. FEBS Lett. 2004;564:312–318. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Abla M, Durand G, Pucci B. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:2084–2093. doi: 10.1021/jo102245c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nath A, Atkins WM, Sligar SG. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2059–2069. doi: 10.1021/bi602371n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhang Q, Ma X, Ward A, Hong W-X, Jaakola V-P, Stevens RC, Finn MG, Chang G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7023–7025. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Chae PS, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16750–16752. doi: 10.1021/ja1072959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Howell SC, Mittal R, Huang L, Travis B, Breyer RM, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9572–9583. doi: 10.1021/bi101334j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Hovers J, et al. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2011;28:171–181. doi: 10.3109/09687688.2011.552440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Chae PS, et al. Chem.-Eur. J. 2012;18:9485–9490. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Schafmeister CE, Miercke LJW, Stroud RM. Science. 1993;262:734–738. doi: 10.1126/science.8235592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) McGregor C-L, Chen L, Pomroy NC, Hwang P, Go S, Chakrabartty A, Privé GG. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Zhao X, Nagai Y, Reeves PJ, Kiley P, Khorana HG, Zhang S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:17707–17712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607167103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Chae PS, et al. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:1003–1008. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rasmussen SGF, et al. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rosenbaum DM, et al. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rasmussen SGF, et al. Nature. 2011;477:540–541. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kruse AC, et al. Nature. 2012;482:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Haga K, et al. Nature. 2012;482:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Manglik A, et al. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Nature. 2012;485:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Chae PS, Rana RR, Gotfryd K, Rasmussen SGF, Kruse AC, Cho KH, Capaldi S, Carlsso E, Kobilka B, Loland CJ, Gether U, Banerjee S, Byrne B, Lee JK, Gellman SH. Chem. Comm. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c2cc36844g. DOI:10.1039/C2CC36844G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kellosalo J, Kajander T, Kogan K, Pokharel K, Goldman A. Science. 2012;337:473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.1222505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Ying GG, Williams B, Kookana R. Environ. Int. 2002;28:215–226. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen HJ, Tseng DH, Huang SL. Biores. Technol. 2005;96:1481–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Kanoh H, Kanaho Y, Nozawa Y. Lipids. 1991;26:426–430. doi: 10.1007/BF02536068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sasaki T, Sonoyama M, Demura M, Mitaku S. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:1131–1137. doi: 10.1562/2005-03-22-RA-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Randhawa P, Park J-S, Sharma S, Kumar P, Shin M-S, Sekhon SS. J. Nanoelec. Optoelec. 2012;7:279–286. [Google Scholar]; (d) Islam MF, Rojas E, Bergey DM, Johnson AT, Yodh AG. Nano Lett. 2003;3:269–273. [Google Scholar]; (e) Li J, Zhang Q, Li H, Chan-Park MB. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:668–673. [Google Scholar]; (f) Heinig K, Vogt C, Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1997;359:202–206. [Google Scholar]; (g) Goni FM, Urbaneja M-A, Arrondo JLR, Alonso A, Durrani AA, Chapman D. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;160:659–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Gurtubay JIG, Goni FM, Gomez-Fernandez JC, Otamendi JJ, Macarulla JM. J. Bioenerg. Biomemembr. 1980;12:47–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00745012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Fernandez J, Demott M, Atherton D, Mische SM. Anal. Biochem. 1992;201:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tiller GE, Muller TJ, Dockter ME, Struve WG. Anal. Biochem. 1984;141:262–266. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Ashani Y, Catravas GN. Anal. Biochem. 1980;109:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mitsuda K, Kimura H, Murahashi T. J. Mater. Sci. 1989;24:413–419. [Google Scholar]; (c) Manhas MS, Kumar P, Mohammed F, Khan Z. Coll Surf A. 2008;320:240–246. [Google Scholar]; (d) Shukla P, Upadhyay SK. Indian J. Chem. 2008;47:1037–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Newstead S, Ferrandon S, Iwata S. Prot. Sci. 2008;17:466–472. doi: 10.1110/ps.073263108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Raman P, Cherezov V, Caffrey M. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2006;63:36–51. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schott H. J. Phys. Chem. 1966;70:2966–2973. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Paradles HH. J. Phys. Chem. 1980;84:599–607. [Google Scholar]; (b) Osawa M, Tong KI, Lilliehook C, Wasco W, Buxbaum JD, Cheng HYM, Penninger JM, Ikura M, Ames JB. J. Mol. Chem. 2001;276:41005–41013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israelachvili JN, Mitchell DJ, Ninham BW. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. II. 1976;72:1525–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laible PD, Kirmaier C, Udawatte CS, Hofman SJ, Holten D, Hanson DK. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1718–1730. doi: 10.1021/bi026959b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caffrey M, Li D, Dukkipati A. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6266–6288. doi: 10.1021/bi300010w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.