Abstract

Background

Contingency management (CM) is efficacious for reducing drug use, but it has rarely been applied to patients with severe and persistent mental health problems. This study evaluated the efficacy of CM for reducing cocaine use in psychiatric patients treated at a community mental health center.

Methods

Nineteen cocaine-dependent patients with extensive histories of mental health problems and hospitalizations were randomized to twice weekly urine sample testing with or without CM for eight weeks. In the CM condition, patients earned the chance to win prizes for each cocaine-negative urine sample. Patients also completed an instrument assessing severity of psychiatric symptoms pre- and post-treatment.

Results

Patients assigned to CM achieved a mean (standard deviation) of 2.9 (1.7) weeks of continuous cocaine abstinence versus 0.6 (1.7) weeks for patients in the testing only condition, p = .008, Cohen’s effect size d = 1.35. Of the 16 expected samples, 46.2% (27.5) were cocaine negative in the CM condition versus 13.8% (27.9) in the testing only condition, p = .02, d = 1.17, but proportions of negative samples submitted did not differ between groups. Reductions in psychiatric symptoms were noted over time in CM, but not the testing only, condition, p = .02.

Conclusions

CM yielded benefits for enhancing durations of abstinence in dual diagnosis patients, and it also was associated with reduced psychiatric symptoms. These findings call for larger-scale and longer-term evaluations of CM in psychiatric populations.

Keywords: dual diagnosis, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, cocaine dependence, contingency management

1. INTRODUCTION

Cocaine use is prevalent in patients with severe and persistent mental illnesses (Mueser et al., 1992; Shaner et al., 1993; Swartz et al., 2006) and negatively impacts outcomes. Substance use in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder has been associated with non-adherence with psychiatric medications (Olfson et al., 2000; Owen et al., 1996), criminal behavior, homelessness, and suicide (Dixon, 1999; Mullen et al., 2000; Wallace et al., 2004).

Contingency management (CM) is efficacious in reducing cocaine use. In CM interventions, patients earn vouchers exchangeable for goods and services or chances to win prizes for submitting negative urine specimens. Controlled studies (Higgins et al., 2003, 2007; Petry et al., 2004, 2005a b c, 2007a; Peirce et al., 2006) and meta-analyses (Lussier et al., 2006; Prendergast et al., 2006) demonstrate that CM is efficacious in enhancing abstinence in patients seeking substance use treatment. The vast majority of CM studies, however, exclude patients with significant and acute mental illnesses.

Although CM has not been evaluated extensively in patients with severe mental health problems, the limited data suggest potential benefits. Ries et al. (2004) found positive effects of a CM approach that used direct access to disability payments as a reinforcer for drug-negative samples. Bellack et al. (2006) randomized dual-diagnosis patients to a group-based behavioral intervention that included vouchers for submitting drug-negative samples or supportive group therapy. Patients in the behavioral intervention reduced drug use compared to those in the supportive therapy group, but the content of the therapy also differed, making it difficult to disentangle the impact of CM.

Several studies have employed reversal designs to isolate the effects of CM on reducing illicit drug use in patients with severe mental health problems. Sigmon et al. (2000) and Sigmon and Higgins (2006) found that the proportion of marijuana negative samples increased from about 10% during a baseline phase to 45% when dual-diagnosis patients were reinforced with large magnitude vouchers. In three patients with schizophrenia, Roll et al. (2004) found that only about 8% of samples were cocaine negative during baseline but 23% tested negative when patients earned vouchers for abstinence.

The purpose of this study was, for the first time, to examine the efficacy of CM for reducing cocaine use in dual-diagnosis patients at a community mental health center. Patients in both groups were reinforced for submitting samples so attendance was expected to be similar between groups. The hypothesis was that CM would decrease cocaine use, as well as psychiatric symptoms.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants were 19 patients receiving treatment at an outpatient mental health clinic between December 2011 and June 2012. Inclusion criteria were age >18 years, cocaine dependence, and English speaking. Potential patients were excluded if they were in recovery from pathological gambling due to potential similarity with the reinforcement procedures (but see Petry et al., 2006).

2.2 Assessments

A research assistant obtained written informed consent, approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board, and conducted study procedures. Demographic and treatment history data were abstracted from clinical records. Patients were administered modules derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (First et al., 1996), and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993), which evaluates severity of past week psychiatric symptoms on a 5-point scale. The Global Severity Index averages overall severity of symptoms, with scores of 0–4; the mean in healthy controls is 0.30 (SD = 0.31; Derogatis, 1993). Participants received a $10 gift card for completing the baseline evaluation and a $20 gift card for the post-treatment evaluation. All but one patient per group completed the post-treatment evaluation (see Supplementary Materials1).

2.3 Randomization

Patients were randomized to one of two 8-week treatments described below after the baseline evaluation. A computerized program stratified patients on opioid dependence and baseline urine sample result.

2.3.1 Standard care

All patients received usual care at the clinic, including individual and group-based psychiatric treatment; substance use treatment was also offered, but not all patients accessed it. In addition, patients were asked to provide urine samples twice per week (e.g., Tuesday and Fridays), which were screened for cocaine using iCup (Instant Technologies, Inc., Norfolk, VA). Patients received a $1 item (e.g., bus token, gift card) for each sample submitted.

2.3.2. Standard care plus CM

These patients received the same care outlined above, including a $1 item for each sample submitted, regardless of results. Additionally, these patients received draws from an urn, with chances of winning prizes, for each cocaine-negative specimen. Number of draws increased by one for each consecutive negative sample, such that the second consecutive negative sample earned 2 draws, the third 3, etc., up to a maximum of 8 draws. In total, patients could earn up to 100 draws. Draws reset to 1 if a cocaine positive sample was submitted or if no sample was provided on a scheduled testing day. After a reset, draws could again escalate for sustained abstinence.

The urn contained 500 cards. Fifty-percent were winning; 250 stated “Good job!” but were not associated with a prize, and 209 were small prizes (choice of $1 McDonald’s coupons, food items, or bus token). Forty were large prizes, worth up to $20 (movie tickets, CDs, watches, etc.), and one was a jumbo prize worth up to $100 (stereo, television, ipod). Cards were replaced following each draw. A variety of prizes in each category were available, and patients were encouraged to suggest desirable prizes.

2.4 Data analysis

Initially, differences in baseline characteristics were evaluated between conditions. The primary dependent measures were percent cocaine-negative samples and longest duration of cocaine abstinence. A week of abstinence was defined as a 7-day period during which all scheduled samples tested negative; if a patient refused or missed a sample, the string was broken. Proportions of negative samples were analyzed in two ways: first, including submitted samples in the denominator (assuming missing samples missing and hence negative), and second, using anticipated samples in the denominator (e.g., 16 samples, assuming missing samples positive). These analyses allow consideration across the full range of possibilities regarding the impact of missing samples. Univariate analyses of variance evaluated group differences in drug use outcomes, controlling for baseline toxicology result, which is known to impact treatment response (Stitzer et al., 2007; Petry et al., 2004, 2012a).

Hierarchial linear models (HLM) evaluated changes in BSI scores from pre- to post-treatment, taking into account within-participants (Level-1) and between-participants (Level-2) values in estimating missing values. Partial regression coefficients estimated intercept and slopes at each level. Models below predicted outcome variable Y from the Level-1 predictor Time and Level-2 predictor Group:

Group was initially coded 0 for standard care, so a significant effect of Intercept (γ10) would indicate that the slope of individuals receiving standard care differed significantly from 0. Models were re-run with CM coded 0 such that significant effects of γ10 indicate changes over time differed significantly from 0 in that condition, and significant effects of slope (γ11) reveal that slopes of the two groups differed. Predictor variables were treated as fixed and entered uncentered, and final estimation of fixed effects (with robust standard errors) is presented.

3. RESULTS

On average, patients were 41.7 ± 9.3 years old with 11.5 ± 4.2 years of education. Forty-two percent were female and 26.3% Hispanic, 68.4% White, and 5.3% multiple races/ethnicities. Primary diagnoses were major recurrent depression (with or without psychotic features) for 47.4%, bipolar disorder for 36.8%, and schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder in the remaining 15.8%. On average, 6.3 ± 11.3 inpatient hospitalizations for psychiatric disorders were documented, and 63.2% were receiving psychiatric disability payments. In addition to cocaine dependence (100%), 36.8% were alcohol dependent, 15.8% marijuana dependent, and 57.9% opioid dependent, all of whom were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance. The two groups did not differ on any baseline characteristics, ps > .28

Number of samples submitted did not differ between groups (Table 1), but less than half the expected samples were remitted. Of submitted samples, about 60% tested cocaine negative, regardless of group. However, CM participants left significantly higher proportions of cocaine negative samples when expected samples were considered, and they achieved significantly longer durations of abstinence. Effect sizes were very large, with Cohen’s ds exceeding 1.

Table 1.

Primary substance use outcomes.

| Variable | Standard care | Contingency management | Group comparison F (16) =, p value | Effect size d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9 | 10 | ||

| Samples submitted | 5.4 (4.5) | 8.0 (5.2) | 1.29, p = .27 | 0.53 |

| Proportion of submitted samples cocaine negative | 60.0 (22.8) | 61.1 (22.5) | 0.01, p = .92 | 0.05 |

| Proportion of expected samples cocaine negative | 13.8 (27.9) | 46.2 (27.5) | 6.65, p = .02 | 1.17 |

| Longest consecutive weeks of cocaine abstinence | 0.6 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.7) | 9.12, p = .008 | 1.35 |

Values represent means (standard deviations).

On average, CM patients earned 29.3 ± 31.3 draws, resulting in $51.12 ± $39.35 in prizes (range $0–$108.78). Three CM patients left 0–1 negative samples and earned 0–1 draw each, and seven left 6 or more negative samples and earned 21–100 draws. In contrast, only one standard care patient submitted more than 6 negative samples.

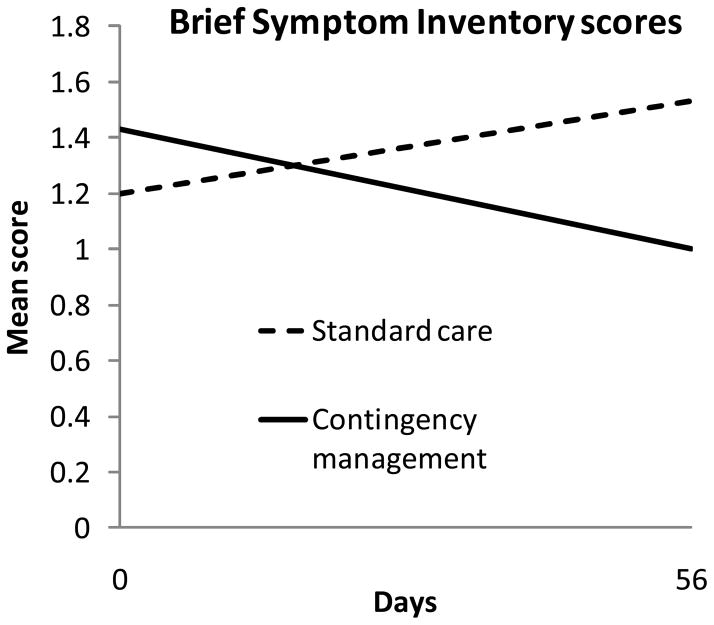

Psychiatric symptoms decreased over time in CM, but not standard care (Figure 1). The β1 coefficient (standard error) for standard care was 0.005788 (0.004506) with T (32) = 1.28, p = .21, indicating no significant change over time in that condition. The respective values for CM were −0.007985 (0.003326), T (32) = −2.40, p = .02, demonstrating a significant negative slope. The treatment condition by time interaction effect was significant, with β1 coefficient of 0.013773 (0.005601), T (32) = 2.46, p = .02. No study-related adverse events occurred.

Figure 1.

Brief Symptom Inventory scores over time by treatment condition. Data are derived from hierarchical linear models analyses as described in the text, and represent group means. Data from patients assigned to the standard care condition are shown in dashed lines, and data from patients assigned to the contingency management condition are shown in solid lines.

4. DISCUSSION

CM evidenced large effect sizes on some, but not all, drug use indices in these patients with severe mental health disorders. Of expected samples, proportions cocaine negative were about three times higher with CM versus standard care, and CM patients were able to achieve on average almost 3 weeks of consecutive cocaine abstinence relative to less than one week in standard care. Seventy percent of patients randomized to CM evidenced a good treatment response of at least 6 cocaine-negative samples versus 11% in standard care.

In concert with the benefits of CM on cocaine abstinence, reductions in psychiatric symptoms were noted. The magnitude of reduction in BSI scores was consistent with that reported with specific psychiatric treatments (Beutler et al., 1991), suggesting potentially clinically significant decreases in psychiatric symptoms with CM. These results indicate that CM has spill-over effects into other areas of functioning. Similar results are reported in primary substance abusing samples. CM has been shown to decrease psychiatric symptoms (Higgins et al., 2003; Petry et al., under review), improve quality of life (Andrade et al., 2012; Petry et al., 2007b), and decrease HIV risk behaviors (Ghitza et al., 2008; Hanson et al., 2008).

Although this study found strong benefits of CM in dual diagnosis patients, some limitations must be noted. The sample size was small, and long-term effects were not evaluated. The intervention was in effect for a brief duration so whether effects could be maintained longer term with (or following removal of) reinforcers cannot be ascertained. Further, effects of CM on proportion of negative samples varied depending how missing samples were considered in the analyses. When missing samples were not included in the denominator, no between group differences were apparent, but benefits of CM were noted when missing samples were factored into the denominator. These contradictory findings depending on how missing samples are handled highlight the need to attain high rates of sample submission to best gauge the impact of treatments on drug use. A $1 incentive for sample submission was insufficient to engender high rates of sample submission in this population.

Despite limitations, this is one of the few randomized studies evaluating CM for reducing illicit drug use in psychiatric patients. It found benefits in this population, for whom CM may have pronounced effects on not only reducing cocaine use but also decreasing ancillary health and mental health service care costs. CM interventions could be adapted to other aspects of psychiatric care including treatment attendance and medication adherence (Petry et al., 2012b). Importantly, benefits can be achieved at fairly low costs, which ultimately may enhance dissemination of CM in this special population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Meg Chaplin, MD, Vamsi Koneru, PhD, and the staff and patients at Community Mental Health Affiliates for their support of and participation in this project, and Trish Lausier for implementing study procedures.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study and preparation of this report was provided by NIDA grants P30-DA023918, R01-DA027615, R01-DA022739, R01-DA13444, P50-DA09241, P60-AA03510, R21-DA031897, and R01-HD075630; NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Clinical Trials Identifier: NCT01478815

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Contributors

Nancy M. Petry designed the study, conducted analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Sheila M. Alessi and Carla J. Rash ensured protocol implementation and data management. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrade LF, Alessi SM, Petry NM. The impact of contingency management on quality of life among cocaine abusers with and without alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2012;21:47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Bennett ME, Gearon JS, Brown CH, Yang Y. A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:426–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, Daldrup RJ, Bergan J, Meredith K, Merry W. Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential, and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:333–340. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring procedures manual-II. Clinical Psychometric Research; Minneapolis, MN: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophr Res. 1999;35(Suppl):S93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Epstein DH, Preston KL. Contingency management reduces injection-related HIV risk behaviors in heroin and cocaine using outpatients. Addict Behav. 2008;33:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson T, Alessi SM, Petry NM. Contingency management reduces drug-related human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors in cocaine-abusing methadone patients. Addiction. 2008;103:1187–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Sigmon SC, Wong CJ, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Donham R, Dantona RL, Anthony S. Community reinforcement therapy for cocaine-dependent outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1043–1052. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dantona R, Donham R, Matthews M, Badger GJ. Effects of varying the monetary value of voucher-based incentives on abstinence achieved during and following treatment among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Addiction. 2007;102:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Bellack AS. Diagnostic and demographic correlates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and major affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PE, Burgess P, Wallace C, Palmer S, Ruschena D. Community care and criminal offending in schizophrenia. Lancet. 2000;355:614–617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, Boyer CA, Walkup J, Welden PJ. Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:216–222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen RR, Fischer EP, Booth BM, Cuffel BJ. Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:853–858. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Kellogg S, Satterfield F, Schwartz M, Krasnansky J, Pencer E, Silva-Vasquez L, Kirby KC, Royer-Malvestuto C, Roll JM, Cohen A, Copersino ML, Kolodner K, Li R. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007a;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T. Contingency management improves abstinence and quality of life in substance abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007b;75:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005a;73:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Barry D, Alessi SM, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. A randomized trial adapting contingency management targets based on initial abstinence status of cocaine-dependent patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012a;80:276–285. doi: 10.1037/a0026883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kolodner KB, Li R, Peirce JM, Roll JM, Stitzer ML, Hamilton JA. Prize-based contingency management does not increase gambling. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Simcic F., Jr Prize reinforcement contingency management for cocaine dependence: integration with group therapy in a methadone clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005b;73:354–359. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, Blaine J, Roll JM, Cohen A, Obert J, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Cowell M, Kirby KC, Sterling R, Royer-Malvestuto C, Hamilton J, Booth RE, Macdonald M, Liebert M, Rader L, Burns R, DiMaria J, Copersino M, Stabile PQ, Kolodner K, Li R. Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs: a national drug abuse treatment clinical trials network study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005c;62:1148–1156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Rash CJ, Alessi SM. Contingency management for drug abuse decreases psychiatric symptoms. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Rash CJ, Byrne S, Ashraf S, White WB. Financial reinforcers for improving medication adherence: findings from a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2012b;125:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treating cocaine users: how low can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99:349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries RK, Dyck DG, Short R, Srebnik D, Fisher A, Comtois KA. Outcomes of managing disability benefits among patients with substance dependence and severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:445–447. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Chermack ST, Chudzynski JE. Investigating the use of contingency management in the treatment of cocaine abuse among individuals with schizophrenia: a feasibility study. Psychiatry Res. 2004;125:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner A, Khalsa ME, Roberts L, Wilkins J, Anglin D, Hsieh SC. Unrecognized cocaine use among schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:758–762. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Higgins ST. Voucher-based contingent reinforcement of marijuana abstinence among individuals with serious mental illness. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Steingard S, Badger GJ, Anthony SL, Higgins ST. Contingent reinforcement of marijuana abstinence among individuals with serious mental illness: a feasibility study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:509–517. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, Petry NM, Peirce J, Kirby K, Killeen T, Roll J, Hamilton J, Stabile PQ, Brown C, Kolodner K, Li R. Effectiveness of abstinence-based incentives: interaction with intake stimulant test results. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:805–811. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Miller DD, Wagner HR, Reimherr F, Swanson JW, Khan A, Stroup TS, Canive JM, McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, McGee M. Substance use and psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia among new enrollees in the NIMH CATIE study. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1110–1116. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace C, Mullen PE, Burgess P. Criminal offending in schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by deinstitutionalization and increasing prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:716–727. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.