Abstract

Due to cell-to-cell variability and asymmetric cell division, cells in a synchronized population lose synchrony over time. As a result, time-series measurements from synchronized cell populations do not reflect the underlying dynamics of cell-cycle processes. Here, we present a branching process deconvolution algorithm that learns a more accurate view of dynamic cell-cycle processes, free from the convolution effects associated with imperfect cell synchronization. Through wavelet-basis regularization, our method sharpens signal without sharpening noise and can remarkably increase both the dynamic range and the temporal resolution of time-series data. Although applicable to any such data, we demonstrate the utility of our method by applying it to a recent cell-cycle transcription time course in the eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Our method more sensitively detects cell-cycle–regulated transcription and reveals subtle timing differences that are masked in the original population measurements. Our algorithm also explicitly learns distinct transcription programs for mother and daughter cells, enabling us to identify 82 genes transcribed almost entirely in early G1 in a daughter-specific manner.

One of the most fundamental processes in biology is the cell cycle, the intricate progression of events necessary for a cell’s division. To better understand how cell-cycle events are regulated, studies in many organisms have monitored the dynamics of various molecular species (e.g., transcript levels, protein levels, nucleosome positions) throughout the cell cycle. Ideally, the dynamics of these species would be studied within individual cells traversing the cell cycle.

Unfortunately, current technology enables accurate, genome-wide quantification of many molecular species only in populations of cells. To provide insight into the dynamics of cell-cycle processes, the cells in such a population should be as synchronized as possible as they progress through the cell division cycle. To effect this synchrony, cells are arrested or selected at one stage of the cell cycle and then released to progress through subsequent division cycles. Molecular species can then be measured in the population at various time points after release (1–5).

Measurements of cell populations would not be substantially different from average measurements of individual cells if the cells in the population were always perfectly synchronized. However, perfect cell synchrony is neither attainable at synchronization nor maintainable after release. Cells exhibit variability even at the time of release, and synchrony deteriorates further over time because individual cells progress through the cell cycle at different rates. Moreover, asymmetric cell division is a major source of synchrony loss in many kinds of cells and especially in budding yeast (6–10). After yeast cell division, newborn daughter cells are smaller than their mothers, and the cycle period of daughters is significantly longer than that of mothers. This is most likely due to mechanisms—not yet well understood—that delay daughter cells in early G1 until they achieve a critical cell size (11). Mother cells are often already larger than this critical size and thus progress more rapidly through G1 (12).

For these reasons, time-series measurements of a population of cells do not accurately reflect the dynamics of individual cells as they traverse the cell cycle, but instead represent the convolved dynamics of all cells in the imperfectly synchronized population. Thus, observed population measurements are only a “blurred” view of the underlying behavior of individual cells, and this view becomes increasingly blurry as the time course progresses.

A few studies have attempted to deconvolve time-series microarray data to survey either transcript levels (13, 14) or peak expression timing (15) during the cell cycle in budding yeast. These approaches modeled variability in cell-cycle progression rate, but ignored the significant synchrony loss caused by asymmetric cell division. As a result, they may not be well suited to budding yeast data and certainly cannot distinguish the cell-cycle transcription programs of mother and daughter cells. Another more recent study (16) developed a transcription deconvolution method for Caulobacter cells that was used to deconvolve the transcription profiles of 10 cell-cycle–regulated genes in that bacterium (see Table S1 for detailed comparisons of these various methods).

Here, we present a branching process algorithm for deconvolving time-series data collected from populations of cells progressing through the cell cycle. The algorithm accounts for the effects of asymmetric division and can estimate separate dynamic profiles for individual mother and daughter cells. Our deconvolved profiles represent the behavior of the average single cell and exhibit increased dynamic range and temporal resolution, but owing to our effective wavelet-based regularization strategy, remain smooth and do not amplify noise. Although our approach applies equally to time-series measurements of various molecular species in various kinds of cells, we demonstrate its utility by producing accurate, high-resolution transcription profiles in mother and daughter yeast cells, genome-wide.

Results

General Algorithm for Deconvolving Time-Series Data from Synchronized Cell Populations.

Our deconvolution algorithm is built upon CLOCCS (characterizing loss of cell-cycle synchrony) (17–19), a framework for quantitatively determining cell-cycle distributions in population synchrony experiments. CLOCCS explicitly models a population of cells using a branching process to account for the division of cells during a synchronized time-series experiment. In the present work, we decomposed the full branching process of CLOCCS into four kinds of intervals: recovery (R) represents the interval immediately following release from synchrony, during which initial cells recover from the synchrony protocol; G1 and daughter-specific G1 (DG1) represent G1 phases of mother and daughter cells, respectively; and post-G1 represents the interval immediately following G1 or DG1, during which mother and daughter cells progress through S, G2, and M. According to this model, after synchrony release, cells progress through the R interval before entering a standard cell cycle (G1 followed by post-G1). At the end of the first cycle, cells divide into mother and daughter cells; mother cells enter another standard cell cycle, while newborn daughter cells instead traverse DG1 before entering post-G1. Every time a cell divides, a new branch appears and this process repeats.

Using morphological markers—such as budding index (17), flow cytometric measurement of DNA content (18), and/or fluorescently tagged molecular markers (19)—CLOCCS accurately estimates the lengths of cell-cycle intervals, the variance in the rate at which cells move through these intervals, and the positions in the cell cycle at which specific events take place, such as when DNA replication starts or ends. Most relevant for our purposes here, CLOCCS parameters can be used to precisely estimate how cells in a population are distributed over the cell cycle at any point in time following synchrony release.

From CLOCCS parameter estimates, our algorithm constructs a convolution kernel to describe how cells in the synchronized population are distributed along the cell cycle for each time point at which molecular species are measured. We choose to represent the convolution kernel as a matrix (H) transforming unobserved average single-cell dynamic profiles (f) into observed population-level time-series measurements (g). This representation, and the formulation of our problem, is illustrated in Fig. 1A in the context of transcription data; although we demonstrate the utility of our algorithm using transcription data, the approach is general and can be applied to population-level measurements of any kind of cell undergoing any kind of dynamic cell-cycle process.

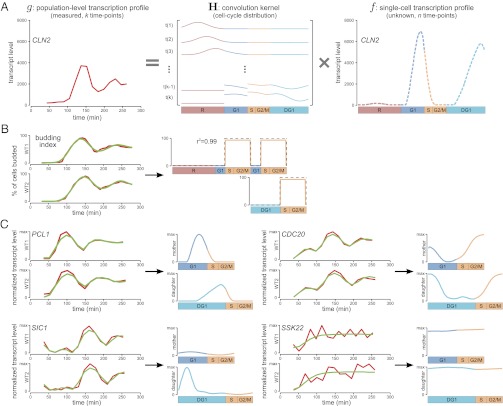

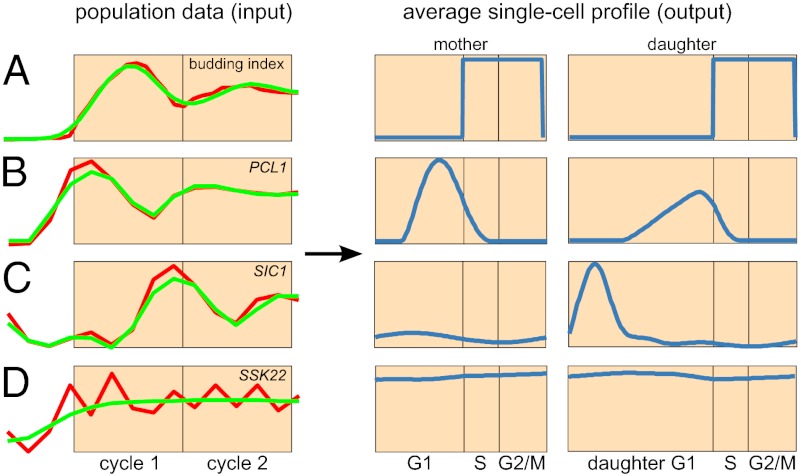

Fig. 1.

Deconvolution recovers average single-cell profiles from population-level data. (A) Algorithm overview. Deconvolution is formulated as an ill-posed discrete inverse problem g = H × f, in which g is a column vector containing the measured population-level time-series data (for example, the transcription profile of the G1 cyclin CLN2; Left, red), H is the convolution kernel calculated from CLOCCS parameters, and f is a column vector representing the components of the unknown dynamic profile of an average individual cell, which is to be estimated. After regularizing using a wavelet basis, our optimization algorithm learns smooth estimates for the four components of f, corresponding to the intervals R, G1, post-G1, and DG1; we consistently color these intervals red, blue, orange, and cyan. Thus, the algorithm takes g as input and learns f as output, yielding an average single-cell profile whose dynamic range and temporal resolution have been dramatically increased (as illustrated here by CLN2). (B) Joint deconvolution of replicate budding index measurements. (Left) The two replicate wild-type budding index measurements in red, along with the fit to those time series learned by our algorithm overlaid in green. (Right) The deconvolved budding profile, learned jointly from the two replicates. The true budding profile is shown as a dashed line for comparison (r2 = 0.99). (C) Joint deconvolution of replicate transcription profiles for four representative genes. Shown for each gene are two replicate measured transcription profiles in red, the fit to those time series learned by our algorithm overlaid in green, and separate deconvolved transcription profiles for mother and daughter cells. To facilitate cross-comparison, all transcription profiles are normalized so that their maximum levels are the same height; consequently, the increased amplitude produced by deconvolution is not apparent (dynamic range before and after deconvolution for these genes is shown later in Fig. 3A). The cyclin PCL1 peaks late in both G1 and DG1, the APC activator CDC20 peaks during mitosis, and the CDK inhibitor SIC1 is transcribed primarily during DG1. For genes whose two replicate profiles are in poor agreement—such as the MAP kinase SSK22 (Pearson’s correlation = 0.14)—our algorithm removes apparent noise; the resultant deconvolved profile smoothly traces the broad trajectory of measured transcript levels across both replicates.

Each row of the convolution matrix H thus corresponds to a time point and each column quantifies the fraction of cells within a given cell-cycle subinterval at each time point. The task of deconvolution can therefore be viewed as an ill-posed discrete inverse problem. We address the ill-posed nature of the problem—and simultaneously tackle the issue of noise in the input data—by using a wavelet-basis regularization approach (see Materials and Methods for a complete description of our algorithm).

Because of the matrix form of the convolution kernel and its utilization of CLOCCS parameters, our deconvolution algorithm can easily be extended to jointly learn profiles from multiple time-series experiments, which makes the learned profiles more accurate and robust (Fig. S1A). We make use of this feature by deconvolving replicate time-series data throughout the remainder of the paper.

Deconvolving Time-Series Yeast Budding Index Data to Assess Algorithm Accuracy.

Perhaps the most important feature of a deconvolution algorithm is the accuracy of its resultant estimates. To assess the accuracy of our method, we first deconvolve measurements of the budding index because the “true” budding profile is known and thus provides a clear basis for evaluation: Yeast cells produce a bud near the start of S phase and remain budded until the end of M phase. Although each wild-type cell is either budded or not budded, time-course budding index measurements appear like damped sinusoids due to synchrony loss in the population over time (Fig. 1B, Left).

We used CLOCCS parameters learned only from flow cytometry data (18) (i.e., without budding index data) to ensure fair assessment of our algorithm’s accuracy. When the two observed population-level budding index measurements are jointly deconvolved, our algorithm predicts the true budding profile nearly perfectly: The originally measured damped sinusoids become square waves with onset near the start of S and offset near the end of M, as desired (Fig. 1B, Right).

Deconvolving Replicate Microarray Data to Reveal Average Single-Cell Transcription Profiles.

Reassured by the performance of our algorithm on budding index data, we jointly learned deconvolved transcription profiles from two replicate cell-cycle time-course microarray experiments in budding yeast (4). Our decision to keep G1 distinct from DG1 allowed us to capture possibly different transcription programs for mother and daughter cells during G1. However, because both mother and daughter cells subsequently enter a single post-G1 interval, our model assumes that both kinds of cells share a common transcription program in cell-cycle phases after G1.

In these experiments, cell populations were synchronized by centrifugal elutriation, so the majority of initial cells were small cells early in G1. From each of the two biological replicates, 15 samples were collected at 16-min intervals for microarray processing, resulting in transcript data covering about two cell cycles. In addition, for each replicate, 32 samples were collected at 8-min intervals for measuring DNA content by flow cytometry and budding index; these data were used to fit CLOCCS parameters to high accuracy (18) (see Table S2 for detailed CLOCCS parameter estimates).

Thus, the inputs to our algorithm were replicate profiles of transcript levels for 5,670 genes across 15 time points at a temporal resolution of 16 min, along with accurate CLOCCS parameter estimates characterizing the synchrony loss of each replicate. The outputs were 5,670 jointly learned transcription profiles at a nominal temporal resolution of less than 1 min, with distinct transcription programs learned for mother and daughter cells. Representative examples are shown in Fig. 1C (as well as Fig. 1A and throughout the paper); deconvolved transcription profiles for all 5,670 genes are available from our website (http://deconvolution.cs.duke.edu). Collectively, these examples highlight the ability of our deconvolution algorithm to not only sharpen transcription signal, but also smooth out experimental noise.

Deconvolution Is Robust with Respect to Uncertainty in Input CLOCCS Parameters.

One potential concern about the output of our algorithm is that because it relies on posterior mean estimates of parameters from CLOCCS, its output might be sensitive to uncertainty in those parameter estimates. To assess this, we generated a set of 100 deconvolved profiles using 100 random realizations from the CLOCCS Markov chain, rather than using the single posterior mean parameterization. These 100 random realizations reflect our posterior uncertainty about the CLOCCS parameters used as input; differences in the resulting 100 outputs reflect our posterior uncertainty in a deconvolved profile with respect to the posterior uncertainty of CLOCCS.

For each gene, we then overlaid the 100 deconvolved profiles generated with 100 different CLOCCS parameterizations on top of one another to form a composite transcription profile. Composite profiles for four representative genes whose transcripts peak at different times in the cell cycle are shown in Fig. 2A. The posterior uncertainty is so minimal that the 100 different profiles in each composite are nearly identical, although the composite profile for DSE3 exhibits slightly higher uncertainty in the middle of DG1. Nonuniform sampling (collecting data more frequently later in the time course when synchrony loss has accumulated significantly) could perhaps be used in the future to ensure that profiles are equally certain in all intervals of the cell cycle. Nevertheless, even with the uniformly sampled data used here, our deconvolution algorithm is robust enough to the posterior uncertainty in CLOCCS parameter estimates that the profiles generated from 100 different parameterizations are essentially indistinguishable.

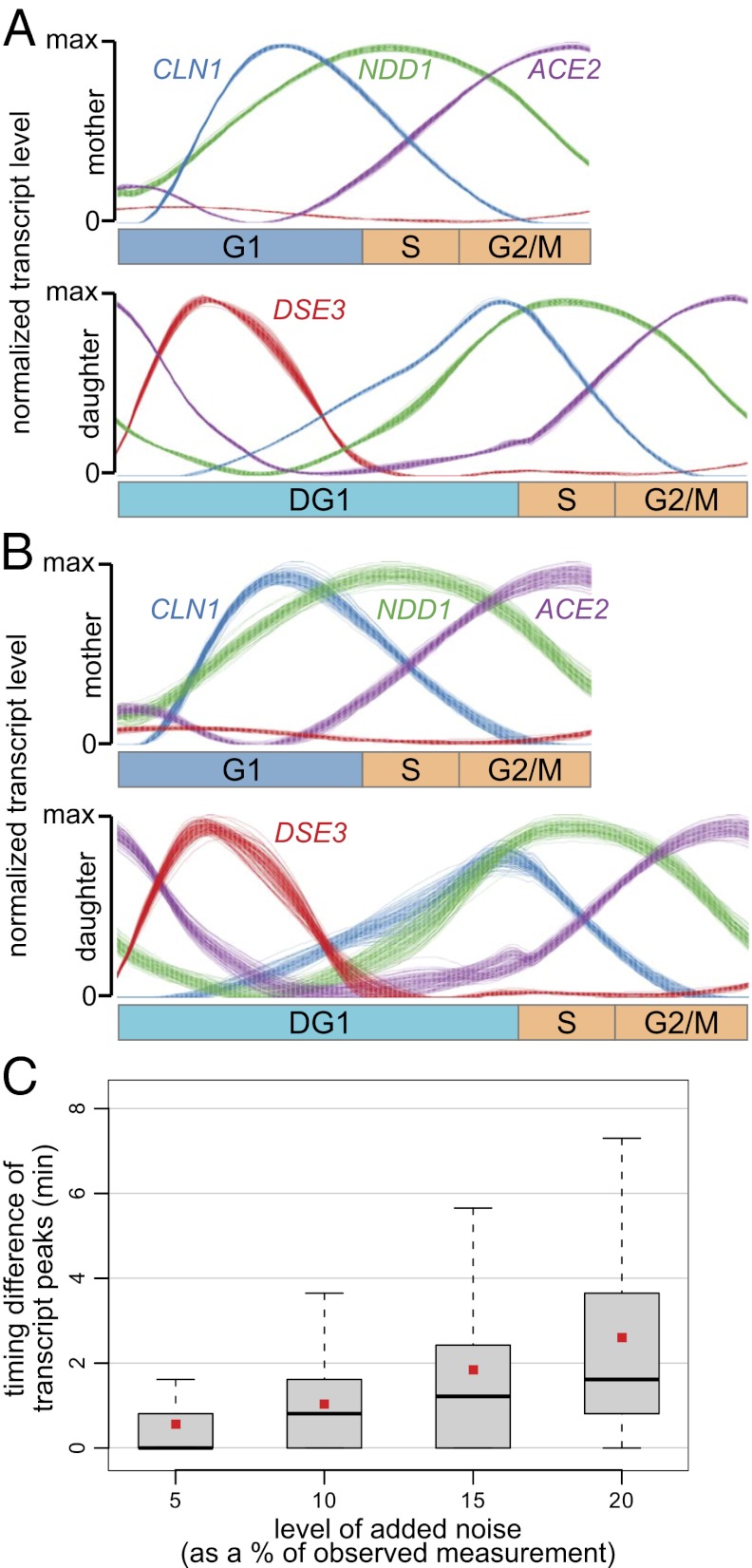

Fig. 2.

Deconvolved profiles are robust to uncertainty in inputs. (A) Robustness of deconvolved profiles with respect to uncertainty in CLOCCS parameter estimates. Shown are 100 overlaid deconvolved transcription profiles for the G1 cyclin CLN1, the S-phase transcriptional activator NDD1, the transcriptional activator ACE2 expressed late in the cell cycle to drive early G1 transcription in a daughter-specific manner, and the daughter-specifically expressed DSE3. The 100 deconvolved transcription profiles for each gene were produced using 100 different CLOCCS parameterizations, each a random realization from the CLOCCS Markov chain. The most noticeable uncertainty in the deconvolved profiles seems to be for DSE3 in the middle of DG1, but even this uncertainty is minimal. Further examples are given in Fig. S2. (B) Robustness of deconvolved profiles with respect to noise in input transcript levels. Shown are 100 overlaid deconvolved transcription profiles for CLN1, NDD1, ACE2, and DSE3. These 100 profiles for each gene were produced by deconvolving 100 different perturbations of the input transcript levels by multiplicative noise at an average of 10%. (C) Effective temporal resolution of deconvolved profiles as a function of measurement noise. The x axis indicates the average level of random multiplicative noise added to input transcript levels at every point in the time series. Box plots display the distribution of timing differences (unsigned) between the transcription peaks of deconvolved profiles with and without noise added. Gray boxes indicate interquartile ranges, thick black bars indicate median values, and small red squares indicate mean values.

Deconvolution Increases Temporal Resolution and Precision of Transcription Profiles.

One particularly compelling property of a good deconvolution algorithm is the increased temporal resolution of its estimates; for example, although the microarray data used in this paper were collected at 16-min intervals, our deconvolved transcription profiles have a nominal temporal resolution of less than 1 min. However, this is by construction; a more meaningful question is, What is the “effective temporal resolution” of our deconvolved profiles?

One way to assess effective temporal resolution is to determine how much the timing of a profile changes as varying levels of noise are added to the input data; this yields a measure of the robustness of timing information to noise in the data. As an example, we show composite transcription profiles for the same four representative genes after input data are perturbed by an average of 10% multiplicative noise in Fig. 2B. We sought to quantify the consequences of such perturbations to the input data on temporal resolution and precision. One simple means of determining how much the timing of a profile changes is to focus on how much the timing of the peak shifts, especially because the peak is typically the most salient feature in a deconvolved profile. We therefore assessed how much peak timing shifted—whether earlier or later (using unsigned timing differences)—as the input data were perturbed by varying amounts of multiplicative noise.

Although the reproducibility of our two replicate microarray experiments was high (4), and although it has been shown that the intrinsic noise level in the gene expression of budding yeast is relatively low (20), we chose to examine the effects of perturbation by multiplicative noise across a broad range, from an average of 5% up to 20% noise. Across this range, the median unsigned peak timing shift ranged from 0.0 up to 1.6 min, and the mean ranged from 0.6 up to 2.7 min (Fig. 2C). As one specific example, if the input replicate transcript levels were all perturbed an average of 10% as in Fig. 2B, the timing of a peak would shift an average of 1 min. This indicates that the peak timing information in our deconvolved profiles is relatively precise and robust to noise in the measured transcript levels.

We observed that the effective temporal resolution of the deconvolved profiles not only is related to the amount of noise in the input data, but also depends on the time at which genes are transcribed during the cell cycle. For instance, when adding 20% noise, although the mean shift in peak timing for all genes is 2.7 min (Fig. 2C), it becomes 4.4 min for genes whose transcript levels peak late in the cell cycle. This suggests that when collecting time-series measurements during the cell cycle, it may again be beneficial to use nonuniform sampling, as suggested above.

Deconvolution Increases Amplitude and Dynamic Range of Transcription Profiles.

Because convolution is a form of smoothing, and deconvolution is therefore a form of sharpening, deconvolution helps restore the dynamic range of transcript level fluctuations whose measured levels have been dampened by the effects of convolution. However, a serious risk of deconvolution is that it will sharpen not only the dampened signal but also any noise in the measurements. For this reason, it is critical that the deconvolution objective be regularized appropriately, which we have achieved in our algorithm through use of a wavelet basis. The result is a deconvolution algorithm that effectively sharpens signal (thereby increasing dynamic range) without sharpening noise (Fig. 1C).

To assess this on a genome-wide scale, we need to quantify the dynamic range of transcription profiles before and after deconvolution. To this end, we developed a simple peak-to-trough ratio (PTR) score. To be robust against the influence of large or small outliers, we defined our PTR score as the ratio between the 80th percentile and the 20th percentile of transcript levels over the course of the cell cycle (ignoring the recovery interval R, during which many stress-response genes are temporarily transcribed at very high levels; see Materials and Methods for further details).

PTR scores before and after deconvolution are illustrated in the density scatterplot of Fig. 3A. Two things are apparent from this scatterplot: The vast majority of genes exhibit a noticeable increase in their PTR score (they appear above the diagonal), as would be expected for a deconvolution method that sharpens transcription profiles; at the same time, owing to the wavelet-based regularization used by our algorithm, and in contrast to most earlier deconvolution methods (e.g., ref. 15), genes can have smoother transcription profiles after deconvolution than before (they can appear below the diagonal).

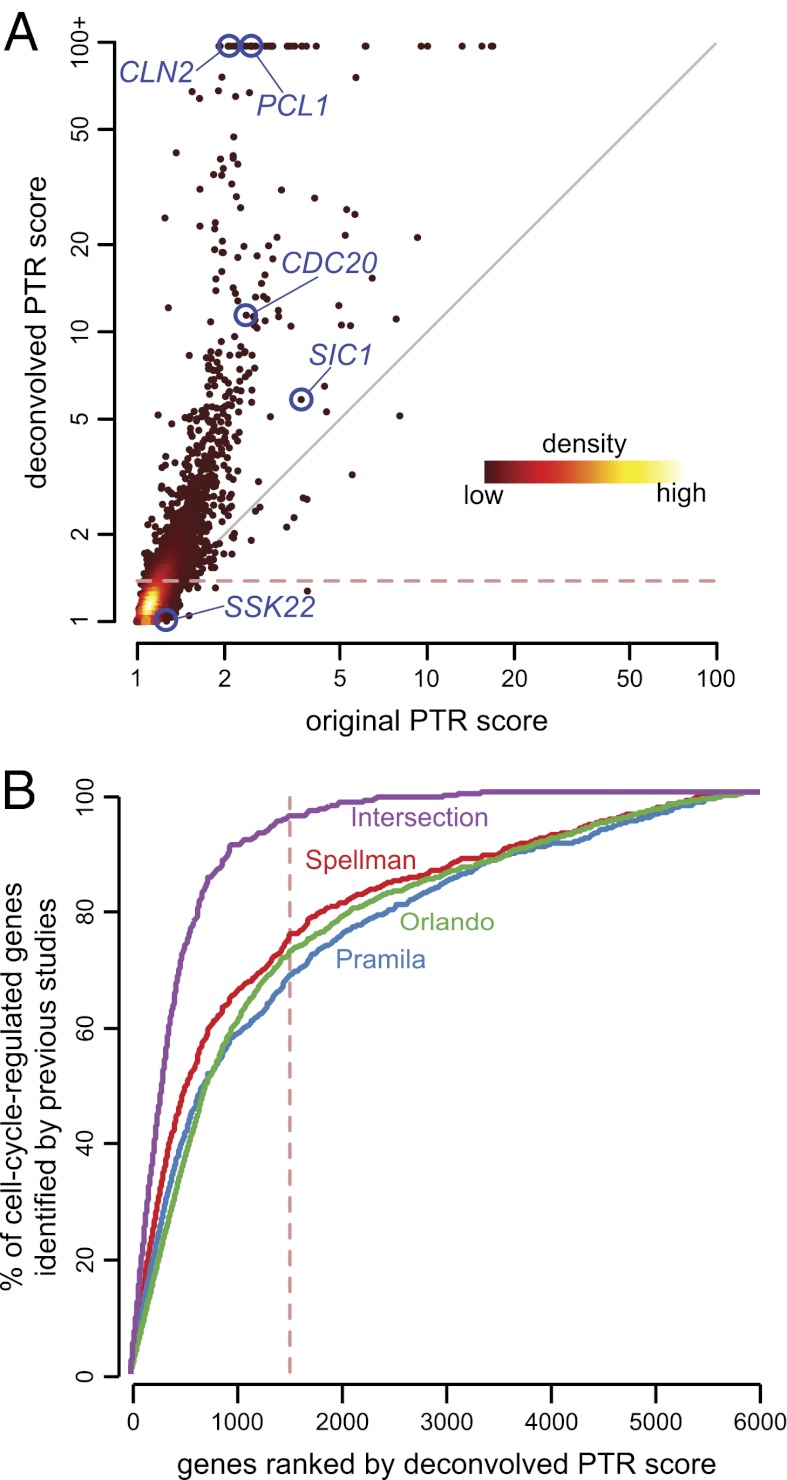

Fig. 3.

Genome-wide analysis of deconvolved transcription profiles reveals a large number of transcripts fluctuating during the cell cycle. (A) Dynamic range of transcription profiles before and after deconvolution. The density scatterplot depicts PTR scores for all 5,670 transcription profiles before and after deconvolution. PTR scores above 100 are shown truncated because the PTR score can become arbitrarily large if the denominator approaches zero. Note that although most genes have increased dynamic range after deconvolution (above diagonal), some genes have decreased dynamic range (below diagonal), owing to our wavelet-based regularization. The five genes whose deconvolved transcription profiles appear in Fig. 1 are highlighted in blue. The dashed red line indicates the deconvolved PTR score threshold corresponding to the 1,500 most strongly cell-cycle–regulated genes. (B) Recovery of yeast genes labeled in previous studies as cell-cycle–regulated. We ranked all 5,670 genes by their deconvolved PTR score. The plot shows the cumulative recall (sensitivity) of recallable genes from previous studies. Genes with the highest 1,500 PTR scores (dashed red line) include 96% of the 440 genes labeled by all three earlier studies as cell-cycle–regulated.

Deconvolution Reveals a Large Number of Transcripts Fluctuating During the Cell Cycle.

The increased dynamic range resulting from deconvolution affords us the opportunity to more sensitively identify transcripts whose levels fluctuate significantly over the course of the cell cycle. Indeed, one nice aspect of our PTR score is that it provides a direct and continuous measure of exactly this. In particular, combining our model-based deconvolution with our PTR score allows us to avoid the Fourier-based periodicity analyses that have been used to label cell-cycle–regulated genes in the past (e.g., refs. 1, 21), with their attendant limitations when applied to sparsely or irregularly sampled time-series data.

Transcripts cannot be categorized in a simple binary fashion as being cell-cycle–regulated or not, because cell-cycle regulation occurs along a continuum from strongly regulated to weakly regulated; moreover, the locations of genes along this continuum are surely condition and strain dependent. For this reason, it makes more sense to simply rank genes in terms of their degree of cell-cycle regulation in our data, for which we use our deconvolved PTR score as a measure. To visualize how well our deconvolved PTR score recovers genes labeled by earlier studies as being cell-cycle–regulated, we plotted the cumulative recall of previously labeled cell-cycle–regulated genes as a function of our deconvolved PTR rank (Fig. 3B).

Bearing in mind that the degree of cell-cycle regulation occurs along a continuum, we chose to focus on the top 1,500 genes for downstream analysis, corresponding to a deconvolved PTR score ≥1.37 (shown in Fig. 3 A and B by a dashed red line). This set includes 73% of the 1,271 periodic genes identified in ref. 4, 69% of the 895 recallable periodic genes identified in ref. 3, 76% of the 709 recallable periodic genes identified in ref. 1, and 96% of the 440 genes in the intersection of the three previous lists. Note that because these previous studies made predictions without the aid of deconvolution, we should not expect to see overwhelming agreement with any individual study.

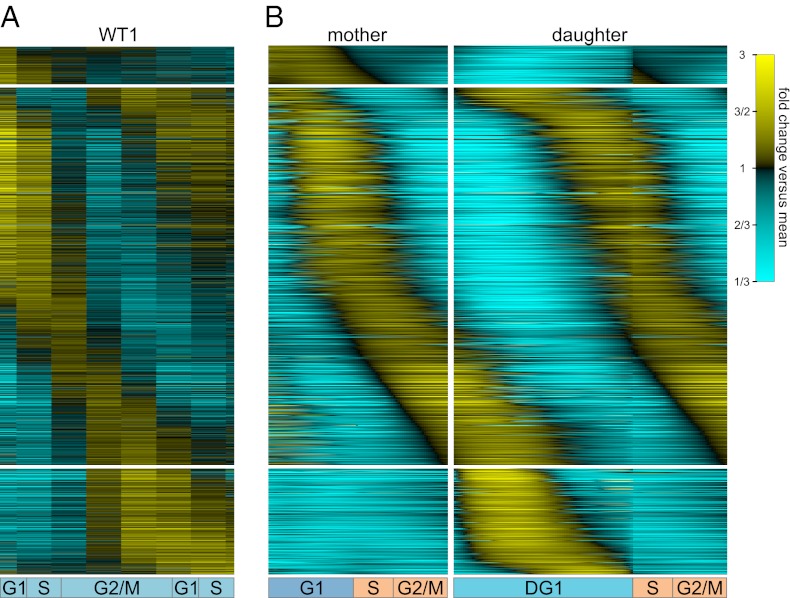

The PTR scores of the top 1,500 genes increased by a factor of 4.7 on average after deconvolution (after capping deconvolved PTR scores at 100). The increased PTR scores following deconvolution allow us to more sensitively identify genes whose transcript levels fluctuate during the cell cycle. Heat maps of transcript levels for the top 1,500 genes before and after deconvolution are shown in Fig. 4 (heat maps of transcript levels learned from single experimental replicates are shown in Fig. S1B).

Fig. 4.

Transcript dynamics of 1,500 most strongly cell-cycle–regulated genes. Heat maps depict the dynamics of transcripts in the measured (A) and deconvolved (B) transcription profiles of the 1,500 most strongly cell-cycle–regulated genes. Corresponding rows in the various heat maps represent the same gene. Note that although our algorithm learns the deconvolved transcription profiles from two independent replicates of the measured data, only WT1 is shown in A for space (WT2 data are nearly identical).

Although we focus on the 1,500 genes whose transcript levels are most strongly cell-cycle–regulated, we reiterate that this is an arbitrary cutoff on a continuum; it is likely that many other genes are weakly regulated over the course of the cell cycle. This raises the prospect that a more significant fraction of the yeast transcriptome may be under cell-cycle control than previously suspected.

Deconvolution Reveals Fine Timing of Transcription Programs.

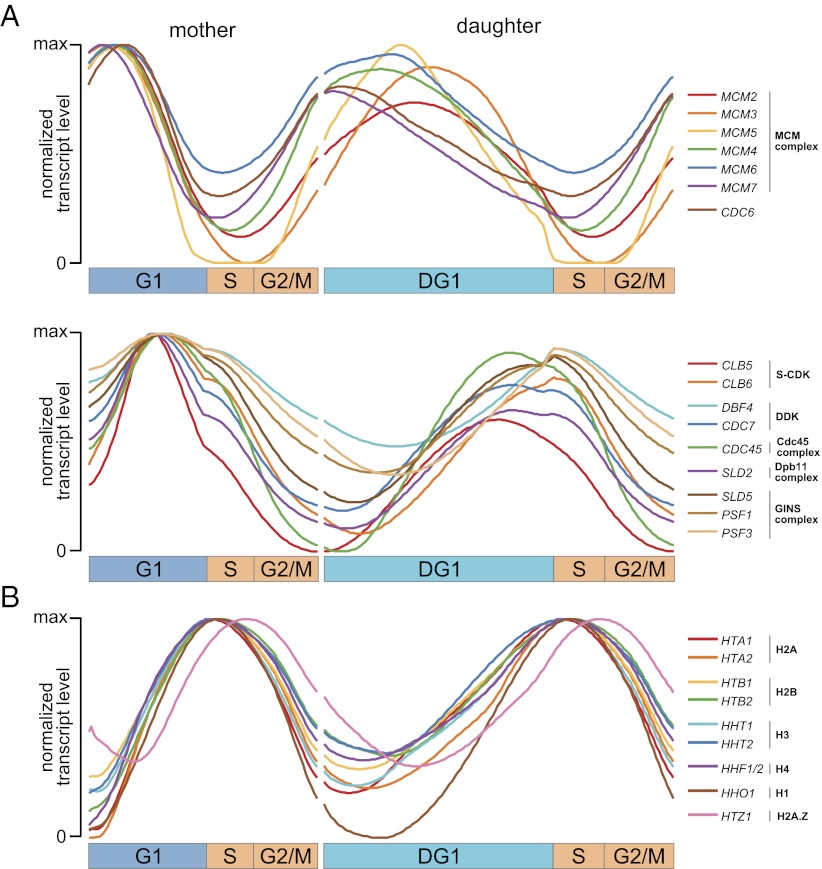

We have shown that our deconvolution algorithm can reliably estimate transcription profiles at fine temporal resolution. This enables us to distinguish subtle timing differences previously obscured in population measurements taken only every 16 min. Fig. 5 provides two examples: the transcription profiles of genes that play key roles in the selection and activation of origins of DNA replication (Fig. 5A) and the transcription profiles of histone genes (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

High temporal resolution of deconvolution reveals fine timing of transcription programs. (A) Normalized deconvolved transcription profiles of genes playing key roles in the origin-selection (Upper) and origin-activation (Lower) steps of DNA replication. Profiles of CDT1, MCM10, SLD3 (in the Cdc45 complex), DPB11 (in the Dpb11 complex), and PSF2 (in the GINS complex) are not shown because their deconvolved PTR scores fall below the PTR threshold of our top 1,500 genes [none of these five are identified as cell-cycle–regulated in any previous study (1, 3, 4) except for PSF2 in ref. 4]. (B) Normalized deconvolved transcription profiles of histone genes in yeast. Note that the only two histone genes with somewhat distinctive profiles are the H2A.Z histone variant which peaks later and the H1 linker histone whose transcript levels approach zero during DG1. Fig. S3 shows an alternative representation of all these profiles.

Origins of replication are selected and activated by the ordered assembly of protein complexes on the genome at discrete stages of the cell cycle. Potential origins are initially marked by the arrival of the origin recognition complex (ORC). During G1, the ORC then associates with Cdt1 and Cdc6 to recruit the helicase MCM complex, forming the prereplicative complex (pre-RC) and licensing potential replication origins for activation. Origins are activated late in G1 by S-CDK and DDK activity, leading to the formation of a massive protein assembly called the preinitiation complex (pre-IC), including the Cdc45 complex, the Dpb11 complex, and the GINS complex. Assembly of the pre-IC eventually leads to the initiation of DNA synthesis, defining the start of S phase (22).

Fig. 5A makes evident that the timing of transcription of genes involved in the selection (pre-RC) and activation (pre-IC) steps of replication is tightly regulated, with transcripts of pre-RC genes peaking together early in G1 (Fig. 5A, Upper) and transcripts of pre-IC genes peaking together later in G1 (Fig. 5A, Lower). The two catalytically distinct MCM subgroups, Mcm2-3-5 and Mcm4-6-7 (23), seem to be transcribed coordinately, especially in relation to the troughs of each profile. Interestingly, the tight regulation evident in mother cells appears to be relaxed in daughter cells, although it should be recalled that daughter profiles are slightly more uncertain. Even so, the transcripts of all of the pre-RC genes still peak before the transcripts of all of the pre-IC genes.

During replication, newly synthesized DNA is complexed with nucleosomes, histone octamers consisting of two copies of each of the four core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (24). Fig. 5B reveals that these core histones are transcribed in remarkably tight coordination, peaking precisely at the start of S phase. In addition, we observe that in both mother and daughter cells, one histone gene peaks distinctly later than the others: HTZ1, the replication-independent histone variant H2A.Z that is not assembled into nascent nucleosomes, but is exchanged for H2A in a subset of nucleosomes afterward (25). The other histone gene with a somewhat distinctive transcription profile is the H1 linker histone HHO1 (26), whose transcript levels uniquely approach zero during DG1, although they peak at essentially the same time as the core histones.

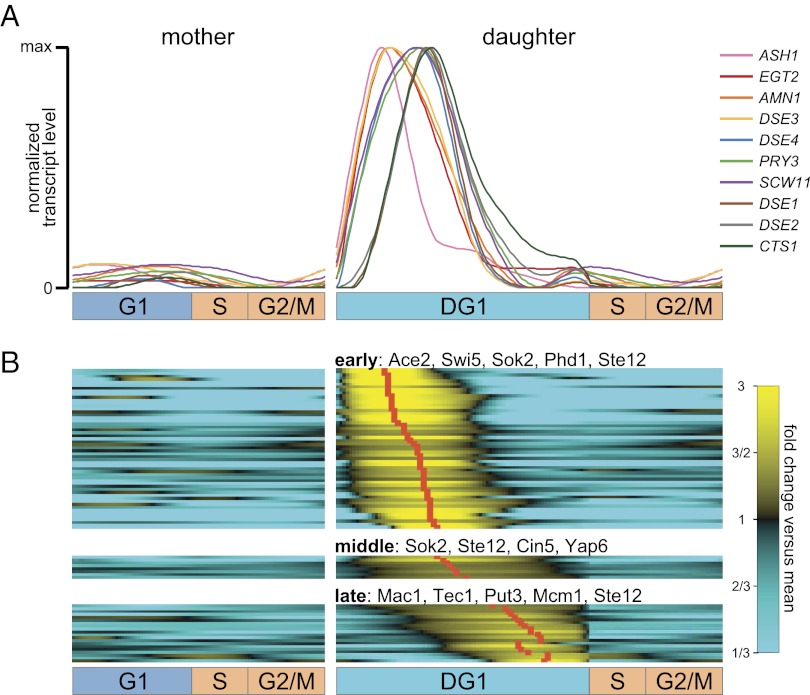

Deconvolution Reveals a Daughter-Specific G1 Transcription Program.

Coupled with our high-resolution estimates, the explicit modeling of asymmetric cell division enables us to monitor and differentiate distinct mother and daughter transcription programs. For example, Colman-Lerner and colleagues (27) identified a set of genes that are transcribed in daughter-specific early G1 and suggested that this daughter-specific transcription may, in part, be due to Cbk1/Mob2-dependent activation and localization of the Ace2 transcription factor to the daughter cell nucleus. As shown in Fig. 6A, our deconvolution algorithm not only correctly predicts the transcription of these genes as daughter specific, but also provides a finely timed view of relevant events in late mitosis and early G1 that are not evident in the input population-level transcription profiles. We observe four distinct sets of transcription dynamics: (i) ASH1 is transcribed to peak levels first, but is also degraded first; (ii) EGT2, AMN1, and DSE3 transcript levels rise very closely on the heels of ASH1, but degrade more slowly; (iii) DSE4, PRY3, and SCW11 transcript levels begin to rise at a similar time, but reach their peaks more slowly; and (iv) DSE1, DSE2, and CTS1 transcript levels begin to rise noticeably later and peak last (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Branching process construction enables deconvolution to reveal a daughter-specific G1 transcription program. Our deconvolution algorithm explicitly learns distinct cell-cycle transcription programs for both mother and daughter cells, enabling us to explore transcriptional behavior of daughter cells that cannot be observed from the population-level transcription profiles. (A) Deconvolved transcription profiles in mother (Left) and daughter (Right) cells of genes previously characterized as daughter-specific by Colman-Lerner et al. (27). (B) Two criteria were used to identify 82 genes transcribed primarily and almost entirely in the DG1 interval (which we call daughter-specific genes). All daughter-specific genes in A were identified by our criteria and thus appear again in this set. According to the timing of transcription peaks in DG1, we classified these genes into three subclusters: early, middle, and late. Up to five overrepresented TFs of each subcluster are shown (full list in Table S3).

This order of transcription timing is consistent with our knowledge about the functions of these genes. Ash1 is one of the earliest regulators of daughter-specific gene expression programs and is required to repress the transcription of HO from the beginning of DG1 to block mating-type switching (28, 29). AMN1 is also transcribed very early in DG1 since Amn1 has been shown to be part of a daughter-specific switch that helps cells complete mitotic exit (30). On the other hand, DSE2 and CTS1 (chitinase) are transcribed later in DG1 as they encode proteins that degrade the cell wall from the daughter side, leading to mother–daughter separation (27, 31, 32).

Among genes that rise to their peaks concomitantly, we observe that their transcript levels may decay at different rates; interestingly, these rates are in rough qualitative agreement with a recent global study of mRNA half-lives (33). For instance, among the closely transcribed genes ASH1, EGT2, AMN1, and DSE3, the half-life of ASH1 is shortest (9.35), the half-lives of AMN1 and EGT2 are close to one other (11.02 and 10.67), and the half-life of DSE3 is longest (24.65). Similarly, the half-life of CTS1 (33.38) is significantly longer than those of the other two closely transcribed genes DSE1 and DSE2 (7.64 and 7.49).

Having confirmed that the known daughter-specific transcripts of Colman-Lerner et al. (27) were primarily transcribed during DG1 after deconvolution (Fig. 6A), we sought to identify other genes that were similarly transcribed primarily during DG1. We established two criteria: The integrated transcript level of a gene across all of DG1 should be at least 30% of the total across all cell-cycle branches (R, G1 + post-G1, and DG1 + post-G1), and the peak transcript level in DG1 should be at least 1.5 times higher than the peak during recovery (R) or in mother (G1 + post-G1) cells. We identified 82 genes satisfying these criteria which we consider to be primarily transcribed in daughter cells during G1 (Fig. 6B). Many known daughter-specific genes are in the list, including all 10 genes of Colman-Lerner et al. (27), all 6 genes identified by Di Talia et al. (ref. 34, Text S1, p. 4) as “strongly and fairly specifically activated by Ace2,” and a remarkable 19 of the 22 genes identified by Di Talia et al. (ref. 34, Text S1, p. 4) as “responding to a greater or lesser extent to both Ace2 and Swi5” (P < 2 × 10−33); these include the cyclin Pcl9 and the CDK inhibitor Sic1 that drives cells out of mitosis (35).

Gene Ontology (GO) (36) enrichment analysis indicates that many of the proteins corresponding to these genes play a role in the processes of transcription elongation (P < 3 × 10−8), completion of separation (P < 2 × 10−7), cytokinetic cell separation (P < 2 × 10−6), and cell wall organization or biogenesis (P < 7 × 10−4), etc. We visually clustered the 82 genes into three clusters and performed transcription factor (TF)-promoter enrichment analysis of the genes in each cluster. Not surprisingly, genes whose transcript levels peak early in DG1 (Fig. 6B, early) share Ace2 and Swi5 as key TFs; also identified are Sok2, Phd1, and Ste12, all regulators of pseudohyphal growth. Genes whose profiles are above average for almost all of DG1 (Fig. 6B, middle) are further enriched for Cin5 (previously called Yap4) and Yap6, yeast AP-1 homologs that both recruit the Tup1/Ssn6 repressor under stress conditions (37). Genes whose onset is a bit later in DG1 (Fig. 6B, late) are enriched for Mcm1, Tec1, and Ste12—all involved in responses to pheromone or pseudohyphal growth—as well as Mac1, a copper-sensing TF, and Put3, a regulator of the proline utilization pathway.

Because it is experimentally difficult to measure mother and daughter transcription programs independently, knowledge of daughter-specific events is still rather limited, and high-throughput identification of daughter-specific genes has been an open problem in the field. Our deconvolution algorithm, with its unique ability to reveal a daughter-specific transcription program from population-level data, provides a method for generating hypotheses in this direction and reveals a much larger list of daughter-specific genes than has previously been identified (27). Along with the recent results of Di Talia et al. (34) and others, this list provides a step toward understanding the nature of mother–daughter cell differentiation (further analysis in SI Text 1).

Similar Conclusions Arise from Deconvolving Separate Transcription Data.

We wanted to see whether our results and conclusions might be dependent on the specific transcription data we were using for deconvolution. To explore this, and to demonstrate more concretely the general applicability of our method, we further deconvolved genome-wide yeast transcription data collected by Granovskaia et al. (5). These data differed from ours in a number of important respects. The cells were synchronized using a temperature-sensitive cdc28-13 mutant strain rather than by elutriation; the data were from a single time-series experiment rather than replicate time-series experiments; and the markers that were collected to characterize synchrony loss in the population were different: Orlando et al. (4, 18) collected budding index plus flow cytometric measurements of DNA content, whereas Granovskaia et al. used indices of the fraction of cells with buds, with nuclei across the bud neck, and with divided nuclei.

As a sanity check, we first confirmed that we could accurately reproduce the true budding index profile (Fig. S4). We then confirmed that the 598 periodic protein-coding genes reported by Granovskaia et al. have deconvolved profiles with sharply attenuated noise, smoother signal, and markedly increased temporal resolution (Fig. S5). Other results are also recapitulated: for example, the later timing of HTZ1 expression compared with other histones (Fig. S6) and the daughter-specific expression of the vast majority of our 82 daughter-specific genes (Fig. S7). Complete deconvolved transcription profiles for the more than 6,000 ORFs from Granovskaia et al. (5) are available from our website (http://deconvolution.cs.duke.edu), in addition to our own profiles.

Discussion

The imperfect synchrony of a synchronized population of cells prevents us from directly using populations to precisely observe the dynamics of processes that occur in single cells. In this study, we present a deconvolution algorithm that efficiently removes the effects of synchrony loss from population-level measurements. When applied to recent replicate microarray data, it robustly recovers precise transcription profiles with markedly increased dynamic range and temporal resolution. Our algorithm is built upon the CLOCCS framework that models three distinct asynchrony sources: imperfect synchronization in the initial cell populations, variance in progression rates of individual cells through the cell cycle, and asymmetric cell division. It should be explicitly noted that our deconvolution method cannot assess variability across single cells, which might be interesting, especially for molecular species at very low concentrations where noise plays an important role. Rather, our method provides a high-resolution view of the transcript levels of the average single cell; alternatively, it learns what would be observed if we were to measure a population of cells that starts and remains in perfect synchrony throughout a time course, with mother and daughter cells perfectly separated from one another following cell division.

Our approach has several algorithmic advantages: (i) Our algorithm optimizes a convex objective function and thus has a unique global optimum. Mature convex optimization techniques and implementations enable an optimal solution to be found efficiently; in practice, we can deconvolve a transcription profile in a few seconds in MATLAB running on standard hardware. (ii) By design, deconvolution algorithms enhance the features of blurred population-level measurements to sharpen underlying signal. However, previous deconvolution methods often end up sharpening noise as well. We avoid this problem by formulating an objective function that is Bayesian l1-regularized using a wavelet basis. Such an approach has been used in the signal and image processing communities, where it has been shown to effectively deblur signals and images while smoothing away noise (38); to our knowledge, however, wavelet-basis regularization has not been applied in a branching process context as we require here. The usefulness of this approach is evident, as about one-third of genes had a PTR that decreased after deconvolution, presumably because the fluctuation in measured transcript levels was due to noise rather than cell-cycle regulation. For example, after deconvolution, the constitutively expressed actin gene ACT1 and almost all ribosomal protein genes are essentially flat over the entire course of the cell cycle (Fig. S8). These observations indicate that our deconvolution algorithm can correctly dampen noise even while sharpening signal. (iii) The extensible design of our convolution kernel approach allows us to learn a single transcription profile from replicate time-series experiments, leading to more accurate and robust estimates.

A further advantage of our deconvolution algorithm is that when applying it to population-level measurements of transcript dynamics across the yeast cell cycle, it can learn distinct cell-cycle transcription programs for mother and daughter cells, because we explicitly model them as distinct within the branching process. Our algorithm identifies 82 genes that appear to be transcribed specifically in daughter cells, and we anticipate this finding will be useful for studying late mitotic and early G1 cell-cycle events, as well as cell differentiation in yeast. Moreover, the ability to distinguish programs for biologically relevant subpopulations is not limited simply to mother and daughter cells in budding yeast; by modifying the underlying branching process model, this feature of our deconvolution algorithm could be extended to other systems and thereby lead to the identification of transcription programs that occur only in distinct subpopulations of cells.

Because mother and daughter cells are permitted by our model to transcribe genes differently during G1, it might be interesting to ask how the transcription programs in G1 and DG1 are related. For example, the transcription program of a gene in G1 may be essentially identical to that in DG1, albeit proceeding at a faster pace so that the profile appears to be compressed, an example being MCM7 (Fig. 5A); or the transcription profile in DG1 may be a delayed-onset version of the G1 profile, preceded by some daughter-specific early G1 profile, an example being MCM3 (Fig. 5A). For each gene, we can calculate two Pearson correlation coefficients: one between the G1 profile and a compressed version of the DG1 profile and the other between the G1 profile and the latter segment of the DG1 profile. Because correlation ignores amplitudes, we also compare the maximum transcript levels in these intervals to ensure rough equivalence. Focusing on the cell-cycle–regulated genes that have clear peaks in G1 and DG1, we observed that about 30% are exclusively in the first category, about 30% are exclusively in the second category, and about 20% can be classified into both categories, like CDC6 (Fig. 5A); the final 20% are not easily categorized (details in Fig. S9).

Our deconvolved estimates show a significant increase in amplitude of cell-cycle oscillation for most of the genes measured. The top 1,500 genes all exhibit transcript levels that are at least 37% higher at the 80th percentile of expression than at the 20th percentile; it seems reasonable to suggest that at least this many genes may therefore be regulated over the course of the cell cycle (nearly twice as many as were labeled cell-cycle–regulated in ref. 1). Although we do not believe all these genes are exclusively cell-cycle–regulated—for example, some genes with significant stress-response regulation are included (Fig. S10)—it suggests that many genes may exhibit previously unrecognized transcriptional regulation during the cell cycle. On the other hand, we also noticed that some well-studied cell-cycle–involved genes like MCM1 and CDT1 are not in our cell-cycle–regulated set (or any previously established sets, for that matter). One explanation may be that their expression does not vary during the cell cycle. Another explanation is that their expression is variable but regulated posttranscriptionally (i.e., we might see fluctuating expression if we monitored protein abundance or, in the case of kinase targets, abundance of phosphorylated protein). A more remote third possibility is that these genes may be transcriptionally regulated, but transcribed at multiple times during a single cell cycle, possibly because they may play multiple roles; due to convolution effects, the transcription profiles of such genes would be greatly muddled in a cell population, and deconvolving them to achieve sufficiently large PTR scores may be difficult, given the level of noise in microarray experiments.

Although we have demonstrated the usefulness of our algorithm by deconvolving genome-wide transcription profiles from two different datasets, the algorithm is general and can be used to deconvolve many other population-level data sources, such as nucleosome occupancy measurements, protein expression profiles obtained by Western blots, or measurements in organisms other than budding yeast. All the algorithm needs as input are synchrony measurements from CLOCCS or some other distribution model (e.g., the cell-type distribution model used in ref. 16) and time-series measurements to be deconvolved.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Data.

We applied our deconvolution algorithm to learn average single-cell transcription profiles jointly from two independent replicates of cell-cycle synchrony experiments in wild-type budding yeast (4). The experiments collected populations of synchronized early-G1 cells by centrifugal elutriation. Two wild-type time-series replicates were collected with 15 samples taken at 16-min intervals in each, starting 30 min after release in the first replicate and 38 min after release in the second. Both replicates covered approximately two complete cell cycles. For each replicate, both budding index and flow cytometry data were collected 32 times at 8-min intervals, starting 30 min after release (18). Budding index was measured by light microscopy to record the number of budded and unbudded cells observed out of at least 200 cells. The DNA content of 10,000 cells per sample was measured by flow cytometry as described in ref. 39. We downloaded the mRNA expression datasets; for genes with multiple probes, we averaged the transcript levels across the probes. Consequently, we were left with measured transcription profiles of 5,670 unique genes [all data available for download from our website (http://deconvolution.cs.duke.edu)].

Deconvolution Model.

Let f ∈ ℝn be a vector of size n, whose elements represent the average levels of some molecular species in individual cells at various points in the cell cycle; let H ∈ ℝt×n be a convolution matrix that transforms values from the individual cell level to the population level; and let g ∈ ℝt be a measured population-level time-series with t time points. Because we require n > t, given the convolution kernel H and a measured profile g, estimating f involves solving an ill-posed discrete inverse problem: Hf = g (Fig. 1B). To avoid overfitting and to ensure a smooth estimate of f, we used a wavelet-basis regularization approach (40). In detail, we split each gene’s average single-cell transcription profile f into four distinct blocks as f = [fR fG1 fDG1 fpost−G1], representing the transcription profile during subintervals R, G1, DG1, and post-G1, respectively. We expect that the estimated profile [fR fG1 fpost−G1] should be smooth because it prevails during the cell-cycle progression of initial cells, and similarly the profile [fDG1 fpost−G1] should be smooth because it prevails during the cell-cycle progression of daughter cells. Using wavelet-basis regularization, one might then imagine formulating the objective function as

|

where || ⋅ ||1 and || ⋅ ||2, respectively, denote l1 and l2 norms, γ is a regularization control parameter, W1 and W2 are orthonormal wavelet-basis matrices, and w simply scales the two regularization terms to account for the different lengths of the intervals they cover; we always set w = 1.5 because the amount of time spent in R + G1 + post-G1 (regularized by W1) is roughly 1.5 times as long as the amount of time spent in DG1 + post-G1 (regularized by W2).

However, when deconvolving microarray transcription data, use of an l2 norm for (Hf − g) is dubious because it represents an assumption of additive Gaussian error whereas transcript-level measurements collected using Affymetrix arrays are generally presumed to exhibit multiplicative Gaussian error. To model multiplicative error, we transformed Hf and g into log-space, yielding a more appropriate objective function:

|

Unfortunately, this objective function is no longer convex. To recover convexity, we approximated this more appropriate objective function using a first-order Taylor series expansion as

|

which is convex and hence has a unique global optimum. When deconvolving microarray transcription data, we require f ≥ 0 because the actual transcript levels are always nonnegative and use Symlet (n = 5) wavelets because of their smoothness and symmetry properties; similar results are obtained with other high-order wavelet bases. When deconvolving budding index data, we instead use the original objective function of Eq. 1, require f ∈ [0, 1] because the fraction of budded cells is always between 0 and 1, and use Haar wavelets because they result in piecewise constant profiles. In each case, we performed constrained optimization of the respective convex function using the MATLAB convex optimization package CVX, version 1.21 (41, 42).

Constructing a Convolution Kernel.

CLOCCS enables us to determine the cell-cycle distribution of a cell population at any given time and to estimate the fraction of cells within any given cell-cycle subinterval. Using the cell-cycle position distributions from CLOCCS (learned parameters characterizing these distributions for each experiment are listed in Table S2), we can construct a convolution kernel H ∈ ℝt×n, where t denotes the number of time-series observations in the population-level measurements g, and n denotes the total number of subintervals along the various cell-cycle branches. Specifically, hij ∈ H quantifies the fraction of cells within a given subinterval j at a given time i. For the purposes of high temporal resolution, n is chosen much larger than t. In our case, t = 15 and n = 258 because we used a total of 258 subintervals for deconvolving transcription profiles: R has 88, G1 has 42, DG1 has 86, and post-G1 has 42. In implementation, we used padding entries and mirror reflections in both directions of f to remove the edge effects caused by circular wavelet packets (43).

Joint Learning from Multiple Replicates.

Our convolution kernel design allows us to learn a robust single transcription profile jointly from multiple experimental replicates. For example, in our case with two replicate experiments, we can construct convolution kernels H1 and H2 for the two replicates using their respective CLOCCS parameter estimates. To ensure the matrices refer to the same points along the branching process, we used the same number of subintervals on the various cell-cycle branches when constructing both H1 and H2. In this manner, corresponding columns in H1 and H2 represent the same fractional population estimate for the same subinterval along the cell-cycle branches under the two experimental conditions. We then constructed a joint convolution kernel  , where t is the transpose operator. Similarly, we can construct a joint population-level time-series

, where t is the transpose operator. Similarly, we can construct a joint population-level time-series  for a gene with two replicates. Although we have two replicates, we need to learn only a single deconvolved profile f. The only thing we need to do is replace g and H within the objective function with gJ and HJ, respectively.

for a gene with two replicates. Although we have two replicates, we need to learn only a single deconvolved profile f. The only thing we need to do is replace g and H within the objective function with gJ and HJ, respectively.

Selecting a Regularization Parameter.

To select a good regularization parameter γ for each gene (or budding index) that avoids both overfitting and oversmoothing, we first determined a region of γ that represents a reasonable trade-off between the fit term ( in Eq. 1 or

in Eq. 1 or  in Eq. 3) and the smoothness term (||[fRfG1fpost−G1]W1||1 + w||[fDG1fpost−G1]W2||1). Next, we selected a gene-specific optimal regularization parameter γ by calculating the maximum curvature on the L-curve (44) within this region. Precise details for selecting the regularization parameter γ are given in SI Text 2.

in Eq. 3) and the smoothness term (||[fRfG1fpost−G1]W1||1 + w||[fDG1fpost−G1]W2||1). Next, we selected a gene-specific optimal regularization parameter γ by calculating the maximum curvature on the L-curve (44) within this region. Precise details for selecting the regularization parameter γ are given in SI Text 2.

Adjustment of Branching Process Construction from CLOCCS.

The branching process model in our deconvolution algorithm would be identical to that of the original CLOCCS branching process if mother and daughter cells separated immediately upon the completion of mitosis and cytokinesis. In budding yeast, however, mother and daughter cells remain attached to one another for a period after cytokinesis, until the cell walls can be enzymatically detached (32). During this time, although the cells have distinct cytoplasmic compartments and may be executing distinct transcription programs, they appear under a microscope to be a single budded cell, which is how they are counted for the purposes of estimating parameters in the original CLOCCS branching process. When producing transcription profiles, we needed to shift the branching times in our branching process by a suitable duration to compensate.

To estimate the duration of this attachment period, we used as biomarkers four genes, DSE1–4 (Daughter-Specific Expression 1–4), known to have daughter-specific transcription profiles. These are specifically transcribed in the daughter cell early in the cell cycle (27). We calibrated the duration of the attachment period to be the smallest duration such that the deconvolved transcription profiles of all four genes are primarily within DG1. The resultant durations for the two wild-type replicate experiments were 26 and 27 min, respectively; in each case, the duration is around one-third of the cell cycle of mother cells and one-fifth of the cell cycle of daughter cells.

Estimating Sensitivity of Profiles to Uncertainty in CLOCCS Parameters.

To assess the robustness of the estimates of our deconvolution algorithm to uncertainty in input CLOCCS parameters, we generated a set of deconvolved profiles for 20 genes, using 100 different parameterizations from CLOCCS rather than using the single posterior mean parameterization listed in Table S2. To obtain these parameterizations, we ran 10 independent CLOCCS Markov chains with 100,000 iterations after a lengthy burn-in period. Then, we randomly selected 10 parameter estimates from the last 1,000 iterations of each of the 10 Markov chains, resulting in 100 random parameterizations.

Estimating Sensitivity of Profiles to Noise in Experimental Data.

To assess the robustness of the estimates of our deconvolution algorithm to noise in the input transcription profiles, we generated a set of deconvolved profiles for four genes, using 100 perturbed input profiles. For each original input profile g = (g1, …, gt), we perturbed the values by multiplicative Gaussian noise at every time point, such that  , where εi ∼ N(0, σ2), where the noise level σ was chosen to be 0.1.

, where εi ∼ N(0, σ2), where the noise level σ was chosen to be 0.1.

Assessing Robustness of Temporal Resolution After Deconvolution to Experimental Noise.

To quantitatively estimate the robustness of temporal resolution after deconvolution to experimental noise, we added random multiplicative noise to the input profile at every time point and computed the unsigned timing difference between the peak transcript level in the original deconvolved profile and that in the deconvolved profile of the same data with added noise. This unsigned peak timing difference provided a measurement of the sensitivity to noise of the temporal resolution achieved by our deconvolution algorithm.

We selected the top 100 genes ranked by PTR scores before deconvolution as our benchmark, because for these genes, the peaks in the deconvolved transcription profiles are usually easy to ascertain. We say the mother and daughter peaks of a deconvolved transcription profile occur where the transcript levels in the mother and daughter cell-cycle intervals are maximal. If the maximal level in one of those intervals is at least twice as high as that in the other interval, we define this to be the dominant peak; otherwise, we say the profile contains two dominant peaks.

For each input profile g = (g1, …, gt), we perturbed the values by multiplicative Gaussian noise at every time point, such that  , where εi ∼ N(0, σ2), and where the noise level σ was chosen to be one of 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, or 0.2. At each noise level, we generated 10 perturbed transcription profiles for each gene, deconvolved these profiles, and computed the unsigned timing differences of their dominant peaks to those of the original deconvolved profile. With 10 perturbed profiles for 100 different genes, we thus had at least 1,000 unsigned peak differences (recall, some profiles contain two dominant peaks) at each noise level. The distributions of these unsigned differences are displayed in Fig. 2C as box plots.

, where εi ∼ N(0, σ2), and where the noise level σ was chosen to be one of 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, or 0.2. At each noise level, we generated 10 perturbed transcription profiles for each gene, deconvolved these profiles, and computed the unsigned timing differences of their dominant peaks to those of the original deconvolved profile. With 10 perturbed profiles for 100 different genes, we thus had at least 1,000 unsigned peak differences (recall, some profiles contain two dominant peaks) at each noise level. The distributions of these unsigned differences are displayed in Fig. 2C as box plots.

Calculation of Peak-to-Trough Ratio Scores.

We used a PTR scoring scheme to quantitatively estimate the dynamic range of transcription of a gene before and after deconvolution. For a measured transcription profile (before deconvolution), the PTR score was calculated as the ratio between the 80th percentile and the 20th percentile of transcript levels after recovery (from the first G1 to the end of the time course). For a deconvolved transcription profile, we first calculated two PTRs (rm and rd) as the ratios between the 80th percentile and the 20th percentile of the transcript levels in mother and daughter cells, respectively. The deconvolved PTR score of a gene was then computed as the weighted geometric mean of the two:  . A higher weight was placed on the PTR score from the mother because we had slightly more confidence in the overall mother profile (more data available for estimating the corresponding entries in f).

. A higher weight was placed on the PTR score from the mother because we had slightly more confidence in the overall mother profile (more data available for estimating the corresponding entries in f).

Identifying Overrepresented Transcription Factors.

According to the deconvolved transcription profiles, we classified daughter-specific genes and stress-response genes into several subclusters by visual inspection. We expect that the genes with coherent transcription patterns may be regulated by common TFs, and therefore certain TFs might be significantly associated with the promoters of the genes in a given subcluster. To test this hypothesis, we used the TF-gene regulation mappings from the YEASTRACT database (45) (direct evidence only, downloaded February 2011) to look for overrepresented TFs binding to promoters of genes within each subcluster. To determine whether a TF is overrepresented in a specified list of genes, we calculated a P value, using a hypergeometric test, and designated it as being overrepresented if the P value is less than or equal to 0.005. To increase the biological significance of the identified TFs, we removed TFs that bound fewer than three, or fewer than 10%, of the genes in a subcluster.

Deconvolving the Transcription Data of Granovskaia et al.

When deconvolving the transcription profiles of Granovskaia et al. (5), we downloaded all data from the Web. Although the authors report transcription profiles from cells synchronized both with α-factor and using cdc28-13 mutants, they report only data characterizing the degree of synchrony for the latter, so we could learn CLOCCS estimates and deconvolve profiles only for the latter experiment. Subsequent analysis of the resulting deconvolved profiles proceeded in the same manner as with our original deconvolved profiles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Edwin Iversen, Joshua Socolar, Merlise Clyde, Laura Simmons Kovacs, Rebecca Willett, David MacAlpine, and Michael Mayhew for helpful discussions at various points during the development of this algorithm or the writing of this paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. G.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Author Summary on page 3731 (volume 110, number 10).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1120991110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Spellman PT, et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(12):3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho RJ, et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol Cell. 1998;2(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pramila T, Wu W, Miles S, Noble WS, Breeden LL. The Forkhead transcription factor Hcm1 regulates chromosome segregation genes and fills the S-phase gap in the transcriptional circuitry of the cell cycle. Genes Dev. 2006;20(16):2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.1450606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orlando DA, et al. Global control of cell-cycle transcription by coupled CDK and network oscillators. Nature. 2008;453(7197):944–947. doi: 10.1038/nature06955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granovskaia MV, et al. High-resolution transcription atlas of the mitotic cell cycle in budding yeast. Genome Biol. 2010;11(3):R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartwell LH, Unger MW. Unequal division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its implications for the control of cell division. J Cell Biol. 1977;75(2 Pt 1):422–435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lord PG, Wheals AE. Variability in individual cell cycles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 1981;50:361–376. doi: 10.1242/jcs.50.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord PG, Wheals AE. Asymmetrical division of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1980;142(3):808–818. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.808-818.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woldringh CL, Huls PG, Vischer NO. Volume growth of daughter and parent cells during the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae a/α as determined by image cytometry. J Bacteriol. 1993;175(10):3174–3181. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3174-3181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bean JM, Siggia ED, Cross FR. Coherence and timing of cell cycle start examined at single-cell resolution. Mol Cell. 2006;21(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen P, Tyers M. How cells coordinate growth and division. Curr Biol. 2004;14(23):R1014–R1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Talia S, Skotheim JM, Bean JM, Siggia ED, Cross FR. The effects of molecular noise and size control on variability in the budding yeast cell cycle. Nature. 2007;448(7156):947–951. doi: 10.1038/nature06072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bar-Joseph Z, Farkash S, Gifford DK, Simon I, Rosenfeld R. Deconvolving cell cycle expression data with complementary information. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(Suppl 1):i23–i30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu P, Wang ZJ, Liu KJ. Polynomial model approach for resynchronization analysis of cell-cycle gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(8):959–966. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowicka M, Kudlicki A, Tu BP, Otwinowski Z. High-resolution timing of cell cycle-regulated gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(43):16892–16897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706022104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegal-Gaskins D, Ash JN, Crosson S. Model-based deconvolution of cell cycle time-series data reveals gene expression details at high resolution. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(8):e1000460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orlando DA, et al. A probabilistic model for cell cycle distributions in synchrony experiments. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(4):478–488. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.4.3859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlando DA, Iversen ES, Jr, Hartemink AJ, Haase SB. A branching process model for flow cytometry and budding index measurements in cell synchrony experiments. Ann Appl Stat. 2009;3(4):1521–1541. doi: 10.1214/09-AOAS264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayhew MB, Robinson JW, Jung B, Haase SB, Hartemink AJ. A generalized model for multi-marker analysis of cell cycle progression in synchrony experiments. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(13):i295–i303. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raser JM, O’Shea EK. Noise in gene expression: Origins, consequences, and control. Science. 2005;309(5743):2010–2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1105891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Lichtenberg U, et al. Comparison of computational methods for the identification of cell cycle-regulated genes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(7):1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwacha A, Bell SP. Interactions between two catalytically distinct MCM subgroups are essential for coordinated ATP hydrolysis and DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2001;8(5):1093–1104. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hereford LM, Osley MA, Ludwig TR, 2nd, McLaughlin CS. Cell-cycle regulation of yeast histone mRNA. Cell. 1981;24(2):367–375. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamakaka RT, Biggins S. Histone variants: Deviants? Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):295–310. doi: 10.1101/gad.1272805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bustin M, Catez F, Lim JH. The dynamics of histone H1 function in chromatin. Mol Cell. 2005;17(5):617–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colman-Lerner A, Chin TE, Brent R. Yeast Cbk1 and Mob2 activate daughter-specific genetic programs to induce asymmetric cell fates. Cell. 2001;107(6):739–750. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sil A, Herskowitz I. Identification of asymmetrically localized determinant, Ash1p, required for lineage-specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. Cell. 1996;84(5):711–722. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cosma MP. Daughter-specific repression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO: Ash1 is the commander. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(10):953–957. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Shirogane T, Liu D, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Exit from exit: Resetting the cell cycle through Amn1 inhibition of G protein signaling. Cell. 2003;112(5):697–709. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doolin MT, Johnson AL, Johnston LH, Butler G. Overlapping and distinct roles of the duplicated yeast transcription factors Ace2p and Swi5p. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40(2):422–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuranda MJ, Robbins PW. Chitinase is required for cell separation during growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(29):19758–19767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller C, et al. Dynamic transcriptome analysis measures rates of mRNA synthesis and decay in yeast. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:458. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Talia S, et al. Daughter-specific transcription factors regulate cell size control in budding yeast. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(10):e1000221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toyn JH, Johnson AL, Donovan JD, Toone WM, Johnston LH. The Swi5 transcription factor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae has a role in exit from mitosis through induction of the cdk-inhibitor Sic1 in telophase. Genetics. 1997;145(1):85–96. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashburner M, et al. The Gene Ontology Consortium Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanlon SE, Rizzo JM, Tatomer DC, Lieb JD, Buck MJ. The stress response factors Yap6, Cin5, Phd1, and Skn7 direct targeting of the conserved co-repressor Tup1-Ssn6 in S. cerevisiae. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e19060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donoho D, Johnstone I, Johnstone IM. Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika. 1994;81:425–455. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haase SB, Reed SI. Evidence that a free-running oscillator drives G1 events in the budding yeast cell cycle. Nature. 1999;401(6751):394–397. doi: 10.1038/43927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansen M. 2001. Noise Reduction by Wavelet Thresholding, Lecture Notes in Statistics (Springer, New York)

- 41.Grant M, Boyd S. 2008. Graph implementations for nonsmooth convex programs. Recent Advances in Learning and Control, Lecture Notes in Control and Information Sciences, eds Blondel V, Boyd S, Kimura H (Springer, London), pp 95–110.

- 42.Grant M, Boyd S. 2010. CVX: Matlab software for disciplined convex programming, version 1.21. Available at http://cvxr.com/cvx.

- 43.Mallat SG. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing. Burlington, MA: Academic; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen P. Analysis of discrete ill-posed problems by means of the L-curve. SIAM Rev. 1992;34:561–580. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teixeira MC, et al. The YEASTRACT database: A tool for the analysis of transcription regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D446–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]