Heart Failure (HF) is a progressive, life-limiting condition that affects more than 5 million people in the US, with about 550,000 new cases each year. Once HF is diagnosed, the one-year mortality rate is 20% and the 5-year mortality rate over 50%.1

There is a preponderance of evidence indicating that HF exacts a tremendous physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual toll on the people diagnosed with it2–8 and the family members who care for them.2, 9, 10 Multiple research teams have examined the experience of patients with late-stage HF. Participants have repeatedly reported that they experience a wide array of troubling symptoms and are not adequately informed about their disease and its management. Furthermore, evidence indicates that communication, especially about prognosis and treatment planning is particularly problematic, and is associated with adverse outcomes and increased suffering.2, 5, 9, 11, 12

The integration of palliative care (PC) consultation services into late-stage HF care has been suggested as a mechanism for improving the experience of HF patients and their loved ones13–18 for several reasons. First of all, PC practitioners are committed to providing care in physical, psychosocial, and spiritual domains. Palliative care is a philosophy of care intended to improve the quality of life of patients confronting life-limiting illnesses and their families, by preventing and alleviating distress. It is not intended to hasten death, and is appropriate throughout the disease course in conjunction with therapies directed at prolonging life.19, 20 Similarly, the goal of hospice care is to improve the quality of life of patients with life-limiting illness and their families. However, hospice care is tailored to those no longer pursuing primarily curative treatments with life expectancies likely measured in months.21 Palliative care clinicians care for people who choose hospice as well as for those who do not.

Secondly, PC services are now more widely available in the hospital setting; with about 70% of academic medical centers reporting some type of PC program.22 In addition, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that hospital-based PC services are associated with positive outcomes.23–25

However, it is the potential of PC consultations to improve communication around prognosis and treatment planning that is most strongly associated with the calls for increased involvement of PC services in late-stage HF. Much has been written in the PC literature about the central role of communication in high quality palliative care.26–29 In fact, the most common reason that referring clinicians request consultations with PC services is to establish goals of care.30–32 Goals of care discussions involve eliciting patient and family goals, values, and preferences, communicating prognostic information, and articulating potential options for, and outcomes of, treatment, in the context of that patient and family situation.

Increasing numbers of researchers and clinicians have heeded the calls for the integration of PC and HF care for patients with late-stage HF, and initial reports suggest that clinicians are satisfied with collaborative efforts.33–35 However, there is little reported about the perspectives of HF patients and their families on the involvement of PC in their care. We do not know what patients and families expect from PC consultations, what their experiences of these consultations are, and what they feel the role of PC in HF is and should be. The purpose of this study was to address this gap by describing the perspectives of a group of persons with HF and their family members who had been referred to an inpatient PC consultation service. If clinicians in both PC and HF have a better understanding of the experience of HF patients referred for PC consultation, then they can design and implement interventions that would better serve patients with HF and the people who care for them.

Methods

Design

A qualitative descriptive research design was chosen as it is well-suited to describing the experiences and perspectives of participants. In qualitative descriptive research, the investigator remains close to the data and the surface of words and events, seeking an accurate portrayal of the participants' experiences and their perceptions of the phenomenon under investigation.36–38 This study received approval from the university's Institutional Review Board.

Sampling Design and Setting

Purposeful sampling, using a criterion sampling technique39 was used to recruit patient and family member participants over a 9 month period from the inpatient PC consultation service of a 750 bed tertiary academic medical center in upstate New York. The medical center features inpatient and outpatient HF services, and is a designated heart transplant center. In 2010 the inpatient PC service received close to 1000 consult requests, with about 15%, or 150 of those requests for patients with a primary diagnosis of HF. The patient/family member dyad was the population of interest for the study because it is customary for family members to participate in consultations with the PC service.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patient participants

In order to be considered eligible for participation patients were required to be English-speaking adults with a primary diagnosis of HF, who were referred to the inpatient PC consultation service for goals of care discussions. At the time of enrollment, they needed to have either the capacity to give consent or a designated proxy who could provide consent. Persons who were referred to PC for reasons not related to HF, and those lacking capacity to consent or without a designated proxy to provide consent were excluded from the study.

Family member participants

In order to be considered eligible for participation, family members were required to be English-speaking adults, and identified by the patient participant as being involved in either the planning or delivery of his/her care. Any family member whom the patient participant did not want to be involved was not considered eligible.

Data Collection

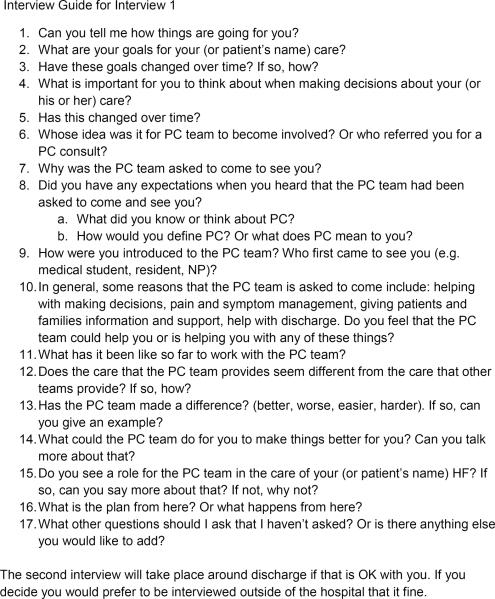

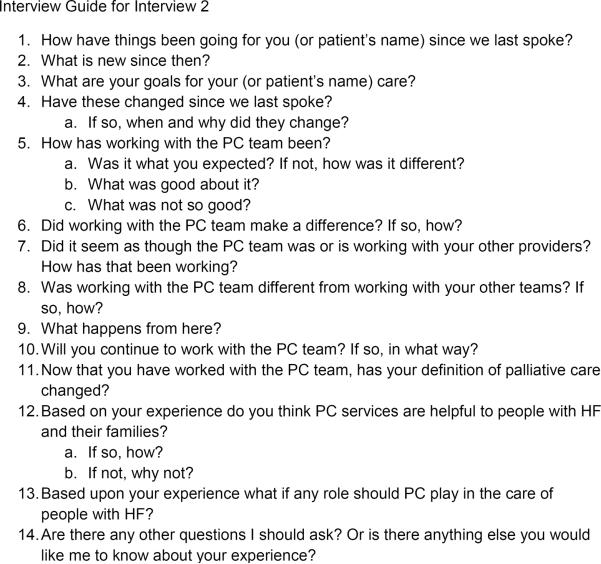

The primary method of data collection was in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted by a single researcher (MM) using interview guides (Figures 1 and 2).36 When possible, 2 interviews per patient/family member dyad were conducted. The main purpose of the second interview was to capture within case changes in perspectives over time. The first interview took place within 48 hours after the PC consult. The second interview was completed around discharge. Interview times were adjusted according to participants' needs and desires. Field notes were recorded after each interview. Data collection and analysis were on-going, simultaneous, and continued until saturation was achieved.40, 41 Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim by and entered into ATLAS-ti, the data management software used in the study, along with field notes as soon as possible after the interviews. Demographic and other clinical information were extracted from the medical record.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to identify themes and patterns in the data.36, 42 Interview transcripts were first read to get a sense of the whole, and then coded line-by-line, using a start list of codes inductively developed from the data.42 Related codes were grouped together into categories. As the analysis proceeded, patterns and relationships, both within and across cases, were sought. This was facilitated by the use of matrices, which displayed coded and categorized data in cells.42 Themes, or expressions describing some aspect of the participants' experience, were derived from this analysis.42, 43

The criteria used to demonstrate that threats to validity or trustworthiness had been adequately addressed are those specified by Lincoln and Guba44 and Maxwell.45 Strategies such as the use of purposeful sampling to guide data collection; the careful documentation (i.e. audit trail) of the entire research process, asking readers with expertise in qualitative methods to conduct parallel analyses; and inviting later participants to provide feedback on themes derived from the data (member checking) were instrumental in maximizing the trustworthiness of the study findings.

Results

Sample Description

During the recruitment period 37 eligible patient participants were identified, and 24 of those were enrolled. The most common reasons given for nonparticipation were the patient and/or family member feeling too overwhelmed, stressed, or fatigued to talk. There were no appreciable differences between the group of participants and those who declined participation. Although the patient/family member dyad was the population of interest, in several cases family members did not participate. Primary reasons for family member non-participation included: request by the patient participant that family members not be approached; inability, due to weather, distance, or lack of transportation, of family members to come to the hospital; and lack of family involvement in patient care. The final sample size was 40 participants; 24 patients and 16 family members. In 3/24 cases, family members participated in interviews without patients because patients had cognitive deficits or reported feeling too fatigued to participate. In 11/24 cases only 1 interview was completed because the initial PC consultations happened very close to the patients' deaths or discharges. In total 40 interviews were completed.

All of the patient participants (Table 1) fit the criteria for NYHA Stage III or IV HF or ACC/AHA HF Class C or D. Most had multiple co-morbidities and had been hospitalized more than once in the previous year. Seven patient participants had ICDs upon admission. Three patient participants had left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), 2 as destination therapy, and 1 as potential bridge to transplant, and 2 were heart transplant recipients. Most participants had significant functional impairment, spent most of their time sitting or lying, and required assist with activities of daily living, but were generally mentally alert and able to take in adequate nutrition. The majority of family member participants (Table 2) were married Caucasian females, either the spouse or adult child of the patient participant.

Table 1.

Patient Participant Characteristics

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number Patient Participants | 24 | |

| Age | Range: 26–93 years | |

| Median: 71 years | ||

| Average: 70 years | ||

| Sex | Male | 15(62.5%) |

| Female | 9 (37.5%) | |

| Race | Caucasian | 20 (83%) |

| African American | 4(17%) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 15(62.5%) |

| Widowed | 5(21%) | |

| Single | 4(16.5%) | |

| Living Arrangement | Lives alone | 6 (25%) |

| With family member | 18(75%) | |

| PC Performance Score (Scale:0–100) | Range: 20–70 | |

| Median: 50–60 | ||

| Hospital Days | ||

| Admission to PC referral | Range: 0–134 | |

| Median: 7 days | ||

| PC consult to D/C or death | Range: 1–23 | |

| Median: 3.5 | ||

| Average: 6 | ||

| Discharge Disposition | Home with VN services | 10(41.6%) |

| Home without services | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Long term care facility | 8 (33.3%) | |

| Acute care facility transfer | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Inpatient hospice | 1 (4.2%) | |

| Death | 3(12.5%) |

Table 2.

Family Member Participant Characteristics

| Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number FM participants | 16 | |

| Age | Range: 29–76 years | |

| Median: 53 years | ||

| Average: 54 years | ||

| Sex | Male | 2(12.5%) |

| Female | 14(87.5%) | |

| Race | Caucasian | 14(87.5%) |

| African American | 2(12.5%) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 14(87.5%) |

| Single | 2(12.5%) | |

| Relationship to Patient | Spouse | 6 (37.5%) |

| Adult Child | 8 (50%) | |

| Son or daughter in-law | 2 (12.5%) |

Study Findings: Organized into 4 Main Themes

Theme 1: Participants had little previous knowledge of PC and formed impressions based on their interactions with the team

1a) The surprise consult

The majority of participants were unprepared for the PC consult. They reported having no or little previous understanding of the term palliative care, and being unaware of the existence of the PC consultation service and/or that a referral had been made.

Those participants, for whom the PC consult was unanticipated, generally reacted initially with suspicion, caution, and/or skepticism. For example, one participant reported that she initially suspected that her cardiologist had enlisted the PC team to convince her to consent to the placement of an LVAD, an intervention she had previously declined. “At first I felt [the HF team] had an agenda. I felt they were introducing me to [PC] to try and persuade me into getting the [LVAD].”

Those participants, for whom the PC consult was expected, generally welcomed it. As one family member said, “I was very interested in talking with them…We want to look at every avenue we possibly can to give Mom the best care and help.”

1b) Forming impressions

After meeting with the PC team nearly all of the participants offered definitions of PC, with many, but not all equating PC with hospice or end-of-life care. They reported that their definitions were based on information from the referring team and/or their interactions, over time, with the PC team. The following is an excerpt from an interview with the family members of a patient who had recently been transferred to the inpatient PC unit. In this case the “stage was set” for PC, meaning that the referring team laid the foundation for the consult so that participants had baseline expectations of the PC team.

[Cardiologist] sat down and said basically… “Decide whether you want us to do everything we can to prolong her life or whether you want us to do everything we can to make what's left of her life more comfortable.” And when he did that he went into and discussed palliative care and the concept behind it…

After meeting with the PC team, the patient chose to redirect to a comfort care approach, reinforcing for this family that PC is synonymous with end-of-life or comfort care.

In the following example, the patient and family experienced a “surprise” consult, meaning that they had no introduction from the referring team, and had never heard the term palliative care. The family member based his definition of PC on his interactions with the PC team. “PC is basically a way to help comfort the family and patient through difficult times… [They] come in here with bad news when you are on your last leg and try to smooth things over and keep you calm and collected.”

In several cases, participants expanded or modified their definitions over time. For example, one patient participant defined PC as “kinda like hospice” during his first interview. By the second interview he described PC this way: “a supportive talking, an all-around help thing. They customize their care to whatever you need.” Similarly, a family member participant who had defined PC as hospice during the first interview, reported that “hospice and PC are different…in PC all of the medical treatment can continue.”

1c) “They come from a different world.”

When asked to compare the PC team to other hospital-based teams, participants generally emphasized differences between them. They attributed these differences primarily to the unique style and focus of the PC team. They described clinicians from the PC service as “listening”, being “more compassionate”, “spending more time”, and having a holistic focus. As one family member said just before her husband was transferred to a chronic care facility,

[PCT] come from a different world …the way they talk to us. Not that others don't care, but [PCT] really, really care. [PCT] goal is the patient, all around, their physical, mental, emotional status. With other nurses and doctors I think that first and foremost they focus on the physical.

1d) Outcomes of PC: “They made it better.”

Participants were asked what they felt were the results of having the PC team involved in their hospitalization. Nearly all reported that working with the PC team had a positive impact on their hospital experience. They felt informed, supported, and reassured as illustrated by the following excerpts:

They straightened out a lot of things for us that we really didn't understand before…different things to help…a different understanding. (Patient (P); interview 2)

I can breathe knowing that he is comfortable. He was in pain and he was comfortable… he is being cared for in a humane, kind, loving way. (Family member (FM); interview 2)

Participants' perceptions of their relationships with the referring team providers influenced whether they viewed the overall outcome of the PC team's involvement as additive or corrective. If patients and family members reported that the care from their cardiology team was good, which in most cases they did, then the PC service was largely seen as additive, or enhancing the good baseline care they were getting from their HF team. For example one patient explained, “Well physically I have a gigantic support team, but the rest of it I don't have anybody filling…I needed a soul to talk to…that really helped me a lot.”

However, if participants were dissatisfied with the care from the referring team, then the PC team was viewed as corrective, addressing perceived deficits in care or clearing up misunderstandings. In the following example, the patient participant felt that the cardiac surgery team was not supportive of her goal, which was to have heart valve repair surgery so that she could participate in a clinical trial. She was unaware that a referral had been made to PC but assumed the reason for the consult was a discrepancy between her goals and those of the referring team. During the first interview she expressed doubts as to whether the PC team would be able to help her, “I am not dying. What can they really do?” By the second interview her opinion had changed. She reported that the PC team explained her options, assisted her with articulating her goals, and then advocated for her to get the surgery.

The [cardiac] team and I were not jiving at all…I knew one thing and they wanted it another way… I think they [cardiac surgery] thought I wasn't going to have any chance at all…The main thing was [PCT] pulled it together, gave me the information which I had tried for weeks to get…I chose this [surgery]… and [PC team] have given me a chance…

Theme 2: Participants described the overall role of PC as one of support

The concrete manifestations of that support included: emotional support in the form of being present, listening, providing reassurance, providing validation; working the system in order to realize patient and FM goals; providing information about treatment/care options, likely outcomes of options, and what to expect; and transitioning to comfort care.

2a) Emotional support

Participants spoke at length about the importance to persons with HF and their family members, of emotional support. Most reported that this piece was lacking in their usual HF care. As one family member participant who had been taking care of her husband with an LVAD reported, “Not only did I feel listened to but then I spent an hour afterward talking about my difficulties in handling the situation…there's a lot of emotional and mental pieces to be worked out that are not supported…”

2b) Working the system

The majority of participants reported that the PC team was involved in activities such as: advocating for them with other agencies or providers, facilitating complicated discharges, coordinating care, arranging and conducting family meetings, and overcoming obstacles in order to assist them in reaching their goals. They used terms such as “customizing care”, “navigating through the available services”, “making it work for me”, “giving me a chance”, and “bringing everybody together”. The term working the system was used to describe these activities. Below are two interview excerpts to illustrate how participants described this phenomenon.

They help families get navigate through the available services and get a plan in place; that is the biggest hurdle. (FM; interview 2)

[PC] are the people that can get things done for you…They are on your side even if you are skeptical that the hospital is on your side…Every person is custom. (P; interview 2)

2c) Providing information

The majority of participants reported that the PC team conveyed information during their hospital stay. Providing information did not make the PC team unique, however, as most clinicians offer information. Rather, differences in the nature and scope of the information distinguished the PC service from other services. According to the participants PC clinicians took a broader approach, discussing all available options, including the option of PC, and what to expect (prognostic information) with respect to the individual patient's situation. This was very much appreciated by the participants. For example, one family member reported during the second interview, that before meeting with the PC team, she and her family felt ill-equipped to make decisions related to her mother's care, as they were unaware of available options. “That is the piece of the puzzle that seemed so overwhelming to us, but it's really not. Once we knew the options we easily came to the decision that she wasn't ready for hospice care.” Another family member, the wife of a man with an LVAD, shared a similar perspective. “They are giving me the options, giving me what's going to happen and what options I have for handling it…”

2d) Transitioning to comfort care

Several participants reported that the PC team was instrumental in facilitating a “smooth” or “easy” transfer from aggressive, disease treatment-driven care to comfort care. A family member, whose mother had been transferred to the PC unit, described it this way: “[PC] is a gift; Mom not in any pain, awake and aware and got to say goodbye to everybody… We're all gonna remember this as a very nice thing.”

Theme 3: Participants had a sense of prognosis which directed treatment goals

All of the participants reported having an understanding of patient prognosis. However, in only half of the cases were the participants' understanding of patient prognosis in agreement with their understanding of the clinician's prognosis. In the concordant cases, that is those cases in which the participants reported agreeing with their understanding of the clinician's prognosis, participants discussed changes over time in their patient care goals based on a shared or agreed understanding of prognosis. With one exception, they all redirected to a comfort care approach. For example, when one patient participant who had been transferred from another facility for an evaluation to determine LVAD eligibility, was asked about her redirection to a comfort care approach she replied, “This is a new goal because I had no idea I was this sick.”

However, in the discordant cases, that is those cases in which participants reported that they disagreed with clinician estimates of prognosis, none of the participants demonstrated changes in goals over time, and all pursued a plan of care that reflected their own understanding of prognosis, which was always more optimistic than that of the clinicians. For example, an elderly woman admitted with an exacerbation of her CHF, and her daughters all disagreed with providers from both the referring and PC teams that she was an appropriate candidate for hospice. Her daughter explained during interview 2, “We certainly recognize that down the road we might be facing that point [hospice]. We don't think we are there yet… she's still gotta lot of life left in her.” They elected to pursue their goal of a “tune-up” followed by discharge home, which was the goal they came in to the hospital with.

Theme 4: The conflation of PC and hospice was a barrier to PC in HF care

Although participants were not asked about hospice in HF care many announced that hospice would not work for them. When asked about the reasons that hospice was not an option for them, participants discussed their understanding of the “rules” of hospice. They explained that these rules were “deal-breakers” for HF patients primarily because they hindered aggressive management of their HF symptoms. For example, one family member reported that when her mother had another exacerbation of HF, which was characterized by severe shortness of breath, the interventions that had been successful in controlling her symptoms would no longer be an option. “If Mom had another episode and wanted the full treatment of IV lasix and the rest of it to bring her back to where she needs to be, that would be inaccessible to her.”

Many participants felt that PC is synonymous with hospice care. In those cases the majority of participants predicted that PC would have no place in their current plan of care. Several suggested however, that PC might play a role “down the road” if the current treatment plan failed and/or their disease became “really fatal.” For those participants who did not define PC as hospice or strictly end-of-life care, continued PC involvement was welcomed, even if participants predicted hospice would not be an option.

Discussion

The findings from this study provided an inside look at the experience of a group of people with HF and their family members who were referred to an inpatient PC team. One striking aspect of their experience was feeling “caught off-guard” for the initial consult. Patients and families' lack of awareness of PC as an option in the management of advanced HF has been previously reported.46, 47 In this study however, not only were participants unaware of the availability of PC, in many cases they were also unaware that a referral had been made and for what reason. This was not viewed as an auspicious start to the relationship.

Those participants who had discussed the referral with the HF team reported that the “stage had been set” for the initial consult. However, the stage was often set by the referring team for PC as strictly end-of-life or hospice care. The conflation of PC and hospice has been identified as a barrier to PC.48–50 The findings shed light on why this is so. Hospice was problematic because the participants believed that electing hospice care was tantamount to declining aggressive symptom management. It is not difficult to understand then, if participants felt that the hospice and PC were synonymous, they were not inclined toward PC.

The findings related to prognosis and its influence of treatment goals and plans, specifically the frequent disagreement between participants' understanding of patient prognosis, and their understanding of the clinician estimates of prognosis, may be better understood in the context of some other recent studies. For example, Evans and colleagues51 and Zier and colleagues52 examined the perspectives of surrogate decision makers of patients in an intensive care setting. They too reported that despite finding prognostic discussions helpful, their participants often doubted clinician estimates of prognosis, and did not use this information alone to determine the direction of care. However, these studies did not include the perspectives of patients, nor did they target perspectives of family members of persons with HF.

Finally, given the evidence that PC improves patient/family satisfaction with care23–25, it was not surprising that the participants indicated that working with the PC team improved their hospital experience. This study however, increased understanding of how the PC service increased participants' satisfaction with care. Many participants focused on improvements in communication processes that they associated with an increase in the quality of care they received. That said the role of the PC service described by the participants encompassed much more than communication. They spoke at length about a primarily supportive role of PC in HF care. Participants wanted the PC team to work with their HF team and fill in the perceived gaps in their current health care.

The study contains certain limitations. In several cases because the initial consult happened very close to patient death or discharge, only one interview was completed. In other cases patients participated without family members. In those cases the perspectives of family members are missing. In addition, only hospitalized patients and their family members who had been referred to one PC service were included. Furthermore, clinicians were not observed or interviewed. Therefore, questions remain about clinicians' definitions of palliative care, their perceptions of patient prognosis, and whether and how they introduced PC.

The research implications of this study are numerous. For example, participants indicated that they were most satisfied with care when they felt that clinicians from both HF and PC worked collaboratively. Therefore, studies to inform the design of an intervention that integrates PC into the care of late-stage HF patients are indicated. Studies comparing the experience of persons with HF who receive the collaborative intervention to that of those who receive usual care could then be conducted.

Results from the study suggest a few practice changes that would improve the experience of hospitalized HF patients and their family members. For a start, Hupcey, Penrod, and Fenstermacher 53urge clinicians to view PC as a philosophy of care that allows for the unpredictable trajectory of HF, rather than a system of care delivery introduced at a specific point in an illness trajectory. This would likely be a more palatable way to introduce PC.

In addition, an explicit and systematic approach to communicating about the referral would benefit patients and family members. Both the referring team providers and PC team members could set the stage for palliative care and ensure that everyone is on the same page, something several participants suggested. Furthermore, clinicians from both HF and PC services could work together to define appropriate “triggers” or indications for referring HF patients for PC consults in their settings. Finally the findings from this study underscore the need to examine current hospice guidelines and modify them to accommodate people with HF.

Conclusion

The majority of patients with HF are never referred for a PC consult. Two of the barriers to referral discussed by the participants in this study are the lack of awareness of the availability of PC and the conflation of PC and hospice. Despite these barriers nearly all participants reported that the PC team improved their hospital experience. Discussions of the role of PC in HF care brought to light gaps in the way we are currently providing care to persons with late-stage HF, and the unique ways in which those gaps are made manifest in the lives of patients with HF and their family members. With the collective energy of health care consumers, researchers, clinicians, and policy makers, care can be improved so that it better meets the needs of patients with HF and the people who love them. A deeper understanding of their perspectives is a step in that direction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Ruth L. Kirchstein National Research Service Award, Fellowship # 1F31 NR012084-01; and Sigma Theta Tau International Epsilon XI Chapter Research Award. The author would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Margaret Kearney, and Susan Ladwig, and of course the participants, to this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldred H, Gott M, Gariballa S. Advanced heart failure: Impact on older patients and informal carers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49:116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, Kutner JS, Peterson PN, Wittstein IS, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2007;13:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennestedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortis JD, Williams A. Palliative and supportive needs of older adults with heart failure. International Nursing Review. 2007;54:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedmann E, Thomas SA, Liu F, Morton PG, Chapa D, Gottleib SS. Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial Investigators. Relationship of depression, anxiety, and social isolation to chronic heart failure outpatient mortality. American Heart Journal. 2006;152:940.e1–940.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walke LM, Byers AL, Tinetti ME, Dubin JA, McCorkle R, Fried TR. Range and severit of symptoms among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:2503–2508. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westlake C, Dyo M, Vollman M, Heywood JT. Spirituality and suffering of patients with heart failure. Progress in Palliative Care. 2008;16:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, Parker C, Seamark D, Gariballa S, et al. Characteristics and views of family carers of older people with heart failure. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2006;12:380–389. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.8.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dracup K, Evangelista LS, Doering L, Tullman D, Moser DK, Hamilton M. Emotional well-being in spouses of patients with advanced heart failure. Heart and Lung. 2004;33:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs JS, McCoy AS, Gibbs LM, Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM. Living with and dying from heart failure: The role of palliative care. Heart. 2002;88(Suppl 2):36–39. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.suppl_2.ii36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: Prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ. 2002;325:929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams KF, Lindenfeld J, Arnold JMO, Baker DW, Barnard DH, Baughman KL, et al. HFSA 2006 comprehensive heart failure practice guideline. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2006;12:e1–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.11.005. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekelman DB, Hutt E, Masoudi FA, Kutner JS, Rumsfeld JS. Defining the role of palliative care in older adults with heart failure. International Journal of Cardiology. 2008;12:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, Grady K, Hershberger RE, Kutner J, et al. Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2004;10:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart S, McMurray JJ. Palliative care for heart failure. BMJ. 2002;325:915–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuart B. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;10:210–228. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care [Accessed 10/10/09];Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. (2nd edition). 2009 at http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/whatispc.asp. [PubMed]

- 20.World Health Organization [Accessed October 10, 2009];Definition of palliative care. 2009 at http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en.

- 21.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [Accessed 8/25/12];Facts and figures on hospice care. (2011 edition). at http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/2011_Facts_Figures.pdf.

- 22.Center to Advance Palliative Care [Accessed November 11, 2009];New analysis shows hospitals continue to implement palliative care programs at a rapid pace: A new subspecialty fills the gap for an aging population. 2008 Apr 14; , from http://www.capc.org/newsandevents/releases/news.

- 23.Finlay IG, Higginson IJ, Goodwin DM, Cook AM, Edwards AG, Hood K, et al. Palliative care in hospital, hospice, at home: Results from a systematic review. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13(Suppl 4):257–264. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higginson IJ, Finlay I, Goodwin DM, Cook AM, Hood K, Edwards AG, et al. Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2002;23:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glare PA, Sinclair CT. Palliative medicine review: Prognostication. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11:84–103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21:507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: Patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2007;3:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homsi J, Walsh D, Nelson KA, LeGrand SB, Davis M, Khawam E, et al. The impact of a palliative medicine consultation service in medical oncology. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2002;10:337–342. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manfredi PL, Morrison RS, Morris J, Goldhirsch SL, Carter JM, Meier DE. Palliative care consultations: How do they impact the care of hospitalized patients? Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2000;20:166–173. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weissman DE. Consultation in palliative medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:733–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson PM, Paull G, Introna K, Cockburn J, Davis JM, Rees D, et al. Integrated, collaborative palliative care in heart failure: The St. George Heart Failure Service experience 1999–2002. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19:68–75. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson MJ, Houghton T. Palliative care for patients with heart failure: Description of a service. Palliative Medicine. 2006;20:211–214. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1120oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zapka JG, Hennessy W, Lin Y, Johnson L, Kennedy D, Goodlin SJ. An interdisciplinary workshop to improve palliative care: Advanced heart failure-clinical guidelines and healing words. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2006;4:37–46. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kearney MH. Levels and applications of qualitative research evidence. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:145–153. doi: 10.1002/nur.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powers BA. Generating evidence through qualitative research. In: Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, editors. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice. Lippincott, Williams, Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed Sage Publications; London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing qualitative research. 4th ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods: Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health. 1995;18:179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:855–866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maxwell JA. Validity: How might you be wrong? In: Maxwell JA, editor. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horne G, Payne S. Removing the boundaries: Palliative care for patients with heart failure. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18:291–296. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Hazeldine C, et al. Improving end-of-life care for patients with chronic heart failure: “Let's hope it'll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won't”. Heart. 2007;93:963–967. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodlin SJ, Trupp R, Bernhardt P, Grady KL, Dracup K. Development and evaluation of the ”Advanced Heart Failure Clinical Competence Survey”: A tool to assess knowledge of heart failure care and self-assessed competence. Patient Education & Counseling. 2007;67:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fogg J. Heart failure and palliative care: Implications in practice. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2009;12:531–536. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0010. doi:10.1089/jpm.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powers BA, Norton SA, Schmitt MH, Quill TE, Metzger M. Meaning and practice of Palliative Care for hospitalized older adults with life-limiting illness. Journal of Aging Research. 2011;volume 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/406164. article ID 406164, 8 pages. doi: 10.4061/2011/406164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans LR, Boyd EA, Malvar G, Apatira L, Luce JM, Lo B, et al. Surrogate decision-makers' perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. American Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2009;179:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-969OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zier LS, Burack JH, Micco G, Chipman AK, Frank JA, Luce JM, et al. Doubt and belief in physicians' ability to prognosticate during critical illness: The perspective of surrogate decision makers. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36:2341–2347. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180ddf9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.Ob013e318180ddf9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hupcey JE, Penrod J, Fenstermacher K. A model of palliative care for heart failure. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. 2009;26:399–404. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333935. Retrieved from http://ajhpm.sagepub.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]