Abstract

The goal of facial transplantation is to transform severely deformed features in a single, complex operation. Although nearly 20 have been completed since 2005, there is limited information about the subsequent psychosocial status of recipients. The purpose of this study is to describe such changes as captured on a variety of psychosocial measures three and six months after full facial transplantation among three adults who all completed a comprehensive psychiatric assessment before the procedure. We hypothesized and found that participants experienced significant improvement on quality of life measures of physical and mental health based on the MOS-SF-12. While the recipients experienced a decline in their physical quality of life in the three months immediately after surgery, they had improvement by six months (p=.02). Overall mental health showed steady improvement from the time before surgery to six months later (p=.04). These changes, however, were not reflected in another popular measure of quality of life, the EQ-5D. There were no changes in participants’ self-esteem or dyadic function over the same period of time. As facial transplantation evolves from being a novel surgical procedure to an increasingly common clinical practice, future efforts to delineate the psychosocial changes experienced by recipients might include mixed methods analyses, with both qualitative and quantitative data, as well as collaborative assessment protocols shared among facial transplantation programs.

Introduction

The goal of facial transplantation is to transform severely deformed features in a single, complex operation.1 Because the face is so closely linked with a person’s identity, it is commonly thought that severe, conspicuous disfigurement can provoke hurtful comments and stares, and result in significant difficulties when meeting new people, and in making new friends and relationships.2 Hence there is an expectation that facial transplantation will result in improved quality of life among its recipients.3, 4

Although nearly 20 facial transplants have been completed since 2005, there is limited information about the psychosocial status of recipients. The 38 year old woman who had the first partial facial allograph in 2005 did not have formal psychological testing either before or after the procedure.5 Nonetheless, her quality of life has been described as improved.6 More quantitative data about psychosocial outcomes were collected subsequently for a 45 year old woman who sustained a gunshot wound to her face, with ensuing legal blindness. This patient was found to have decreased depression, improved quality of life and increased societal integration, but no change in anxiety or self-esteem in her first post-operative year. She did experience increased psychological distress 3 months after the procedure which abated with a change in medications.7

The purpose of this study is to describe the changes in a variety of psychosocial measures three and six months after full facial transplantation among three adults. All completed a comprehensive psychiatric assessment as they were being considered for the procedure, which served as the basis for comparison in the post-operative period. We hypothesized that participants would enjoy improvement on measures of quality of life, mood, and aspects of relationships with others.

Methods

The overall facial transplantation protocol including psychosocial evaluations was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. Participants were asked to complete an initial diagnostic interview with the study psychiatrist before the allographic facial transplantation procedure. The initial interview included the following measures:

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID)8: this interview was administered to assess the presence of current and lifetime major psychiatric disorders including the substance use disorders.

Marlowe Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSD)9: this scale was administered to evaluate the propensity to provide socially desirable responses.

Brief Cope10: this 28 item measure was given to characterize coping style.

MOS-SF-1211: this 12 item measure was given to describe the overall physical and mental health status of participants over the past 4 weeks.

EQ-5D-3L and EQVAS12: this measure was given to assess today’s health related quality of life along five dimensions (mobility, self care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) on one of three levels of severity (no problems, some or moderate problems, or extreme problems) in addition to an individual rating of current health related quality of life along a vertical visual analogue scale where the endpoints are labeled “100=best imaginable health state” and “0=worst imaginable health state.”

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)13: this 20 item measure was given to evaluate current depressive symptoms in the past week.

Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES)14: this 10 item scale was given to measure general feelings about self esteem.

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)15: this 32 item measure was given to evaluate satisfaction and quality in personal relationships as perceived by married or cohabiting couples.

Participants were then asked to complete follow-up evaluations three and six months after their surgery. Measures included the following already described: 1. MOS-SF-12, 2. EQ-5D-3L and EQVAS, 3. CES-D, 4. RSES, and 5. DAS.

Measures were scored according to published instructions. An EQ-5D Index score was calculated based on the US population based preference weights.16 Participants were aware that their responses to the measures would analyzed and presented in the aggregate when possible.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS (version 9.3, Cary, NC). Simple descriptive statistics were calculated and are reported as percentages, means, and standard deviations as appropriate. For those variables with multiple, repeat values, random effects linear regression models were were used in order to adjust for correlation within subjects. Time was used as a categorical predictor first, and then as a linear predictor for trend in the second model.

Results

The mean age of the three participants (2 males, 1 female) was 37.3 (SD=14.9) years at the time of initial evaluation. None was married, although one was in a committed relationship at the time of enrollment. None was currently employed but all had a high school diploma. All three sustained catastrophic injury, with two losing their eyesight. Participants completed their baseline assessment an average of 8 months before their face transplantation surgery.

Baseline assessment of psychiatric illness revealed that one participant satisfied diagnostic criteria for a current panic disorder, one satisfied criteria for lifetime but not current polysubstance use disorder, and one had neither current nor lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. All had an active coping style and used emotional support. Two also used acceptance and one endorsed positive reframing, planning and religion as additional coping mechanisms. All three scored in at least the 97th percentile on the Marlowe Crowne Social Desirability scale.

Serial Measures

Serial measures evaluating relationship quality, self esteem, mood, and physical function were collected and tabulated. Table 1 summarizes study results.

Table 1.

Summary of Outcome Measures

| Outcome | Baseline | Three Months | Six Months | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Change over time* | |||

| SF-12 PCS | 44.6 [26.7, 62.6] | 28.9 [11.0, 46.9] | 47.3 [29.3, 65.2] | 0.02/0.79 |

| SF-12 MCS | 48.5 [39.1, 57.9] | 55.7 [46.3, 65.1] | 60.5 [51.0, 69.9] | 0.15/0.04 |

| EQ-5D | 0.68 [.26, 1.09] | 0.59 [.17, 1.01] | 0.73 [.31, 1.14] | 0.27/0.59 |

| EQ-VAS | 80.0 [65.4, 94.6] | 71.7 [57.0, 86.3] | 84.3 [69.7, 99.0] | 0.33/0.62 |

| CES | 6.67 [−5.78, 19.1] | 7.33 [−5.12, 19.8] | 2.33 [−10.1, 14.8] | 0.61/0.41 |

| SES | 27.7 [23.1, 32.3] | 24.7 [20.1, 29.3] | 27.0 [22.4, 31.6] | 0.47/0.80 |

| Dyad, Total | 121 [−18, 260] | 116 [17, 213] | 109 [10, 208] | 0.73/0.37 |

Random effects model, adjusted for correlation within subject. Time used as a categorical predictor first, and then as a linear predictor for trend

Relationships

Dyadic adjustment was measured using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale which has a theoretical range from 0 to 151. To provide some context, a sample of 218 individuals married an average of 13.2 years had an average score of 114.8 (SD=17.8) whereas a sample of 94 divorced individuals had an average score of 70.7 (SD=).15 In this study, one subject was uninvolved in a dyadic relationship and so did not complete the DAS at anytime. One subject had a score of 121 prior to surgery, then scores of 111 and 119, three and six months respectively after surgery. Another subject did not have a significant relationship before surgery, but established a romantic relationship after the procedure and reported scores of 120 and then 99, three and six months respectively after surgery. Changes in the total DAS score were not statistically significant.

Self-esteem

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale ranges from 0 to 30. Scores between 15 and 25 are within the normal range, whereas a score below 15 suggests low self–esteem. In general, participants had normal to high self esteem scores at all time points without statistically significant changes.

Mood

The CES-D has a possible range of scores from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating the presence of more depressive symptoms. One subject had a CES-D score of 0 at all three time points. The two others had some acknowledgement of depressive feelings, but with a different pattern in each case.. Changes in the CES-D over time for the group were not statistically significant.

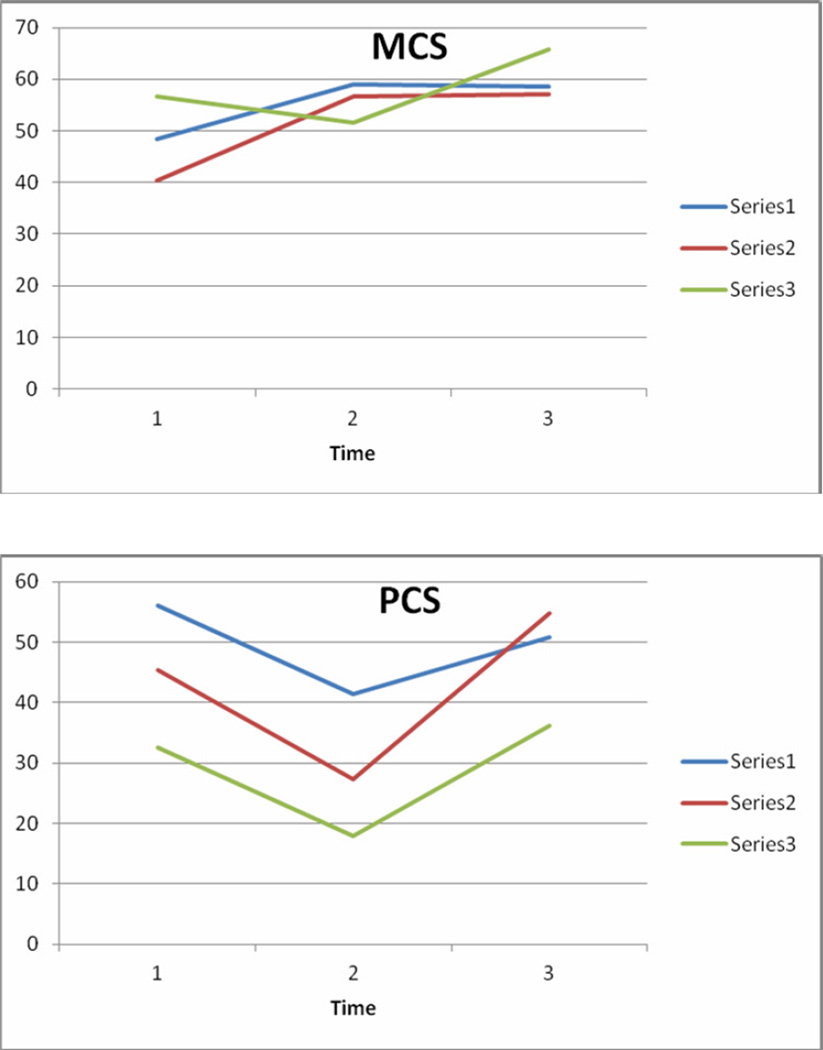

The mental component summary score of the SF-12 (MCS-12) ranges from 0 (worst) to 100 (best), with a national norm mean of 50 (SD=10). The MCS means increased from 48.5 (baseline) to 55.7 (3 months post operatively) and to 60.5 (6 months post-operatively). The trend over time was statistically significant (p=.04). Figure 1 summarizes the change in MCS-12.

Figure 1.

Changes in the SF-12 by Subject

Physical Function

The EQ-5D index score was calculated based on US population based index weights. The index scores range from −0.11 to 1.0, where 0=death and 1.0=perfect health. Both subjects 1 and 2 had consistently high EQ-5D index scores (~.80) whereas subject 3 had worse scores with a noticeable dip 3 months after surgery. The EQ-VAS ranges from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state). Subjects 2 and 3 had similar patterns with no change in estimated health state between the baseline, pre-surgical evaluation and 3 months post-operatively, but with improvement at 6 months. Subject 1 showed the opposite pattern. Overall, changes in the EQ-5D and EQ-VAS were not statistically significant.

The physical component summary score of the SF-12 (PCS-12) ranges from 0 (worst) to 100 (best), with a national norm mean of 50 (SD=10). The overall pattern of the PCS showed a significant decline from baseline (mean=44.6) to 3 months (mean=28.9), with a subsequent upswing at 6 months (mean=47.3) when adjusted for correlation within each subject and time was used as a categorical predictor (p=.02). Figure 1 summarizes the change in PCS-12.

Discussion

This study reports on some of the psychosocial and other quality of life changes in three adults who underwent facial allotransplantations. There were two significant findings, based on the SF-12. First, participants experienced a decline in their physical quality life in the 3 months immediately after surgery, but by 6 months, their physical quality of life as measured on the SF-12 PCS had improved significantly (p=.02). Second, participants’ overall mental health, as measured on the SF-12 MCS, showed significant improvement from baseline to 6 months after the procedure (p=.04).

Several other findings are noted. Participants had very high scores on the Marlowe Crowne Scale, which suggests that they were concerned about “impression management” as they were being considered for the procedure. While understandable, it is possible that their effort to “look good” may have resulted in minimization of problems at baseline and afterwards, making it difficult to measure change. Two adaptive coping styles were common to all three participants: use of active coping and emotional support. Participants reported normal to high self esteem throughout the course of evaluation, exactly as reported in the case study.8 There were no quality of life changes as captured on the EQ-5D or EQ-VAS. Similarly, changes in the total quality of dyadic function were not significant. There was a downward trend in dyadic satisfaction from the time before the procedure to 6 months afterwards (p=.06).

Limitations to the generalizability of results include the small sample size, in addition to the possible response bias already discussed. Others have commented on the dearth of measures tailored to reflect the circumstances of facial allotransplantation.8 Because the procedure is still uncommon, individuals who agree to undergo the surgery may be atypical in ways that are difficult to appreciate. Hence, it is recommended that transplant centers consider selecting several assessment and follow-up measures to be administered collaboratively and consistently to all facial transplantation recipients to strengthen and deepen our knowledge more efficiently. Moreover, future research efforts might use a mixed methods approach that includes both qualitative as well as quantitative evaluation to maximize understanding.

The interaction between psychosocial factors and outcomes for other types of transplantation such as hematopoietic stem cell have been examined.17, 18 Facial transplantation is evolving from a novel surgical procedure to a clinical reality with many unanswered questions.19 This study seeks to clarify some of the unknown psychosocial aspects of facial allotransplantation which have not been consistently evaluated so far. These preliminary data suggest that recipients enjoy improved quality of life with regards to both physical and mental health subsequent to their facial allotransplantation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Endel John Orav, PhD for completing the statistical analysis, Ericka Bueno, PhD, Manager of the Face and Hand Transplantation Programs, and the three patients who completed study measures.

Supported by a research contract (W911QY-09-C-0216) between the Department of Defense and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital under the Biomedical Translational Initiative and K24 AA 000289 (GC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pomahac B, Pribaz J, Eriksson E, Bueno EM, Diaz-Siso R, Rybicki FJ, Annino DJ, Orgill D, Caterson EJ, Caterson SA, Carty MJ, Chun YS, Sampson CE, Janis JE, Alam DS, Saavedra A, Molnar JA, Edrich T, Marty FM, Tullius SG. Three patients with full facial transplantation. NEJM. 2011 Dec 28; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furr LA, Wiggins O, Cunningham M, Vasilic D, Brown CS, Banis JC, Maldonaldo C, Perez-Abadia G, Barker JH. Psychosocial implications of disfigurement and the future of face transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:559–565. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000267584.66732.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker JH, Furr LA, McGuire S, McGuire S, Cunningham M, Wiggins O, Storey B, Maldonaldo C, Banis JC. Patient expectations in facial transplantation. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2008;61:68–72. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318151fa12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prior J, Klein O. A qualitative analysis of attitudes to face transplants: contrasting views of the general public and medical professionals. Psychology and Health. 2011;26:1589–1605. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.545888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubernard JM, Lengele B, Morelon E, Testelin S, Badet L, Moure C, Beziat JL, Dapke S, Kanitaksi J, D’Hauthuillle C, El Jaafari A, Petruzzo P, Lefrancois N, Taha F, Sirigu A, DiMarco G, Carmi E, Bachmann D, Cremades S, Giraux P, Burloux G, Hequet O, Parquet N, Frances C, Michallet M, Martin X, Devauchelle B. Outcomes 18 months after the first human partial face transplantation. NEJM. 2007;357:2451–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petruzzo P, Testelin S, Kanitakis J, Badet L, Lengele B, Girbon J-P, Parmentier H, Malcuis C, Morelon E, Devaulchelle B, Dubernard J-M. First human face transplantation: 5 years outcome. Transplantation. 2012;93:236–240. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823d4af6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffman KL, Gordon C, Sieminow M. Psychological outcomes with face transplantation: overview and case report. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:236–240. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328337267d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV TR Axis I disorders – non patient edition (SCID-I/NP, 11/2002 Revision) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver SC. You want to measures coping but your protocol is too long: consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EuroQuol Group. Health Questionnaire. English version for the US. 1998 http://www.euroqol.org/

- 13.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self reported depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–407. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calculating the US Population-based EQ-5D Index Score. Rockville, MD: 2005. Aug, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/roce/EQ5Dscore.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang G, Orav EJ, McNamara T, Tong MY, Antin JH. Depression, cigarette smoking, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2004;101:782–789. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20431. Published online 30 June 2004 in Wiley Interscience. PMID 15305410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang G, Orav EJ, Tong MY, Antin JH. Predictors of one–year survival assessed at the time of bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:378–385. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.378. PMID 15345782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sieminow M, Ozturk C. Face transplantation: outcomes, concerns, controversies, and future directions. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2012;23:254–259. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318241b920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]