Abstract

There is an ongoing effort to develop better methods for noninvasive detection and characterization of thrombus. Here we describe the synthesis and evaluation of three new fibrin-targeted PET probes (FBP1, FBP2, FBP3). Three fibrin-specific peptides were conjugated as DOTA-monoamides at the C- and N- termini, and chelated with 64CuCl2. Probes were prepared with a specific activity ranging from 10 – 130 µCi/nmol. Both the peptides and the probes exhibited nanomolar dissociation constants (Kd) for the soluble fibrin fragment DD(E), although the Cu-DOTA derivatization resulted in a 2–3 fold loss in affinity relative to the parent peptide. Biodistribution and imaging studies were performed in a rat model of carotid artery thrombosis. For FBP1 and FBP2 at 120 min post injection, the vessel containing thrombus showed the highest concentration of radioactivity after the excretory organs, i.e. the liver and kidneys. This was confirmed ex vivo by autoradiography which showed > 4-fold activity in the thrombus containing artery compared to the contralateral artery. FBP3 showed much lower thrombus uptake and the difference was traced to greater metabolism of this probe. Hybrid MR-PET imaging with FBP1 or FBP2 confirmed that these probes were effective for detection of arterial thrombus in this rat model. Thrombus was visible on PET images as a region of high activity that corresponded to a region of arterial occlusion identified by simultaneous MR angiography. FBP1 and FBP2 represent promising new probes for the molecular imaging of thrombus.

Keywords: fibrin, copper, positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Thrombosis is implicated in a range of diseases such as stroke, heart attack, and pulmonary embolism, which affect millions worldwide.1 Imaging is at the forefront for identifying and monitoring thromboembolic disease. Depending on the anatomical location, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), gamma scintigraphy, computed tomography (CT), or ultrasound can be used to identify thrombus.2, 3 Despite the success of these individual techniques, no single modality currently allows whole body thrombus detection. As a result, the use of multimodal imaging techniques and the development of molecular imaging probes has become the focus of much research for disease detection.

For instance in ischemic (embolic) stroke, there is a 17–30% cumulative recurrent stroke risk over 5 years, with most recurrences occurring in the first year and within the first 90 days.4, 5 The etiology of stroke strongly impacts treatment: for cardioembolic strokes there is a demonstrated benefit to anticoagulant (warfarin) drug treatment in preventing recurrent stroke,6 but in noncardioembolic strokes warfarin (with its greater risk of hemorrhage) is not superior to aspirin in preventing stroke recurrence.7 Despite the importance of the identification of stroke etiology, some 30–40% of ischemic strokes are “cryptogenic,” that is, of indefinite cause, or in other words, the source of the thromboembolism is never identified.8 Underlying sources of cryptogenic stroke include atherosclerosis in the aortic arch,9 intracranial arteries,10 or vertebral artery stenosis;11 or patent foramen ovale, which allows venous thrombus to embolize to the brain12. Plaque rupture in the arch or other major vessels, in particular, is thought to be a major source of cryptogenic strokes13 but can be difficult to detect with routine methods. A single diagnostic test to identify stroke source is urgently needed and would alter treatment in these patients with cryptogenic stroke.14, 15

Multimodal imaging has become increasingly important in clinical practice and preclinical research.16–19 Examples of dual-modality imaging systems include positron emission tomography (PET) combined with CT and PET combined with MRI. In both cases the modalities are complimentary. For instance, the high sensitivity of PET can identify areas of interest and CT or MRI can be used to provide detailed anatomical information. MR-PET offers the advantage of a fully integrated simultaneous system, unlike CT-PET where the sequential collection of images can result in coregistration problems.20

Different molecular targets such as the coagulation enzymes thrombin and Factor XIII, activated platelets, fibrinogen, and fibrin have been utilized for thrombus imaging.21, 22 Of the constituents of thrombus, fibrin is an excellent marker for diagnostic imaging. Fibrin offers the potential for high disease specificity, as it is present in both forming and constituted clots but not in circulating blood. Fibrin is also a high sensitivity target as it is present in all thrombi: venous and arterial, acute and aged. Several groups have targeted fibrin using peptide-based probes23–31, antibodies32, and nanoparticles33–37 as contrast agents for MR, nuclear, optical or CT imaging38. Peptide-based probes in comparison to antibodies and nanoparticles may be more advantageous for imaging solid thrombi because their small size may allow higher potential to penetrate the clot.

We, and others, have previously used the peptide-based fibrin-targeted probe EP-2104R for thrombus imaging in animal models28, 39–44 and clinical trials45, 46. This MRI probe comprises a cyclic six amino acid peptide for fibrin targeting conjugated to 4 Gd-DOTA moieties for MRI signal enhancement. Advances in multimodal imaging, specifically the development of the simultaneous MR-PET scanner led us to realize the benefits of incorporating a PET reporter into EP-2104R. As a result, we have shown simultaneous PET and MR imaging of thrombus using a dual MR-PET probe based on EP-2104R through the partial exchange of gadolinium (III) for copper-64 (64Cu). That study29 suggested the utility of a PET-only probe based on EP-2104R. Notably, the highest concentration of radioactivity, apart from the liver and kidneys, was in the thrombus. There was low background activity in the thorax, neck, head, and blood, suggesting that such a PET probe may be useful in detecting thrombi in the heart, lungs, or carotid arteries. We also noted that MR angiography could be used to precisely localize PET activity within the thrombus containing blood vessel.

In this report we describe our efforts to design a simplified fibrin-targeted PET probe, building on previous work with EP-2104R. We prepared three new peptide-chelate conjugates for fibrin imaging. Each conjugate employs the DOTA-monoamide chelator for 64Cu labeling. We varied the peptide structure to examine the effects of amino acid substitution on thrombus uptake, off-target uptake, and probe metabolism. In addition to the core peptide structure used in EP-2104R, we identified two other similar sequences that were reported to have both high affinity and specificity for fibrin.27, 39, 47, 48 We present here, the conjugation of these fibrin-specific peptides with 64Cu-DOTA to be used as PET imaging probes in a rat model of arterial thrombosis. Using this model, the three PET probes are compared with respect to their biodistribution, metabolic stability, in vivo uptake by thrombus and in vitro fibrin binding affinity in order to demonstrate their potential utility as new molecular imaging tools.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All chemicals were purchased commercially and used without further purification. The three fibrin-binding peptide precursors (Pep1, Pep2, and Pep3) were a gift from Epix Pharmaceuticals (Lexington, Mass). 64CuCl2 was obtained from the Washington University School of Medicine. Gd-DTPA-BSA was synthesized in-house following a published procedure.49

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) - electrospray mass spectrometry (LC-MS), analytical HPLC and radio-HPLC analyses were performed using Agilent 1100 Series HPLC units with a Agilent diode array detector employing a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (100 mm × 2 mm, 5 micron). Reversed-phase semi-preparative purification was performed on a Dynamax HPLC system with a Dynamax absorbance detector using a Kromasil C18 column (250 mm × 20 mm).

Three different HPLC methods were used depending on whether HPLC was being used for purification (Method 1) or to assess purity under neutral (Method 2) or acidic conditions (Method 3). Method 1 used a flow rate of 10 mL/min and the mobile phase A was 95% H2O and 5% CH3CN with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and mobile phase B was 90% CH3CN and 10% H2O with 0.1% TFA. Starting from 5% B, the fraction of B increased to 20% over 5 min, then from 20 to 80% B over 15 min and then from 80 to 95% B over 1 min. The column was washed with 95% B for 5 min and the %B was then ramped to 5%. The system was re-equilibrated at 5% B over 3 min (total time = 30 min); Method 2 used a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and mobile phase A was 10 mM ammonium acetate and mobile phase B was 90% CH3CN 10% 10 mM ammonium acetate. The gradient mobile phase started from 100% solvent A. The fraction of B increased to 80% over 10 min, then the %B was ramped to 0 and the column was equilibrated over 3 min (total run = 13 min); Method 3 used a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid (FA) in H2O and mobile phase B 0.1% FA in CH3CN. The mobile phase was held at 5% B for 1 min then the fraction of B increased to 95% over 9 min. The column was washed with 95% B for 2 min and the %B was then ramped to 5%. The system was re-equilibrated at 5% B over 2 min (total time = 15 min).

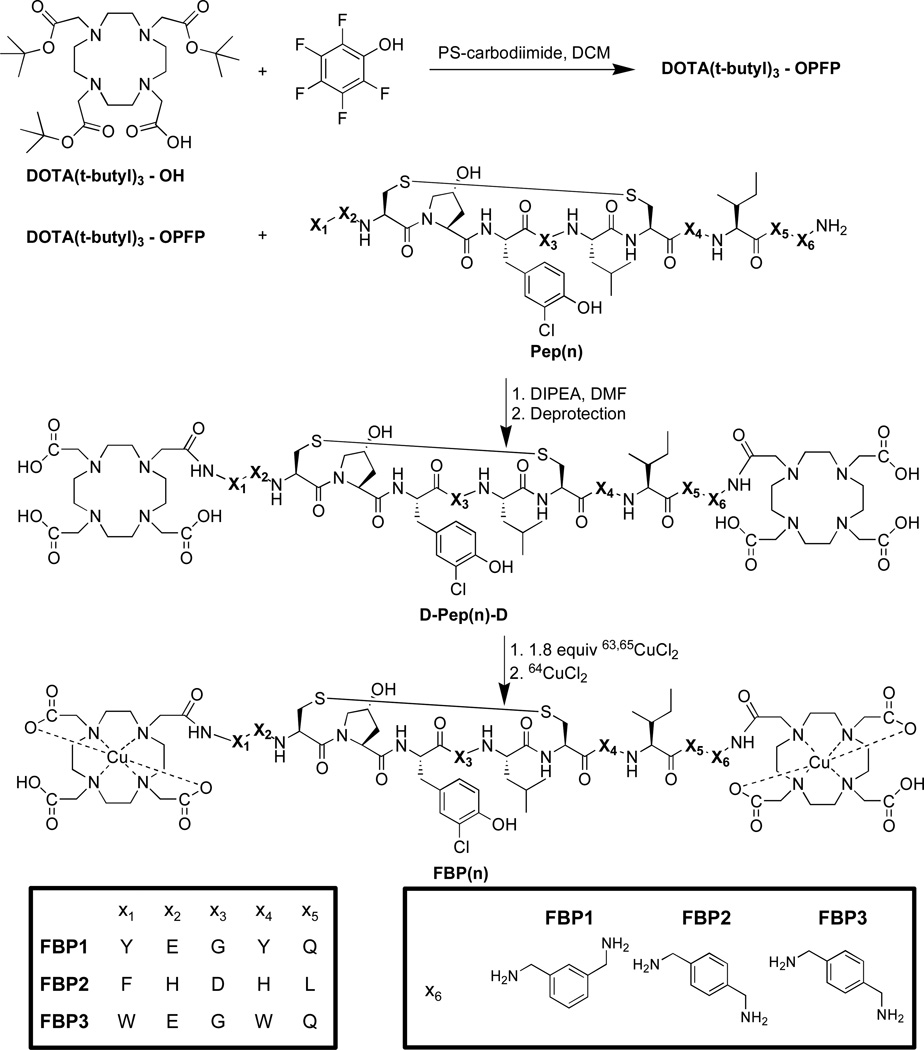

Synthesis

We synthesized three different fibrin-targeted peptides and the corresponding DOTA-monoamide conjugates, and then chelated with the PET isotope copper-64 (64Cu). The synthetic route was the same for each probe. We first conjugated the peptide (Pep(n)) with tri-t-butyl protected DOTA monoacid to give PD-Pep(n)-PD. We then removed t-butyl groups from DOTA resulting in D-Pep(n)-D and our probes, FBP(n), were formed after reaction with 63,65Cu2+ and 64Cu2+. We describe the general synthetic protocol and the specific characterization details for each intermediate and probe.

DOTA(OtBu)3-OPFP ester

Tri-tert-butyl 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetate (DOTA(OtBu)3-OH) (11 mg, 19.2 µmol, 1 eq.) and pentafluorophenol (PFP, 4.2 mg, 23 µmol, 1.2 eq.) were dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM). Polystryrene-carbodiimide resin (PS-DCC, 1.2 eq., 1.26 mmol/g loading capacity) was added to the solution and the reaction vessel was placed on an orbital shaker and monitored by LC-MS using method 3 until all DOTA(OtBu)3-OH was converted to DOTA(OtBu)3-OPFP. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the resin and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product of DOTA(OtBu)3-OPFP was used without further purification as unreacted PFP does not interfere with the next step.

DOTA(OtBu)3-Pep-DOTA(OtBu)3 (PD-Pep(n)-PD)

Three separate reactions were performed in which DOTA(OtBu)3OPFP (5 mg, 6.4 µmol, 1 eq.) and one Pep(n) (Pep1, Pep2 or Pep3) (6.4 µmol, 1 eq.) was dissolved in minimal DMF (< 1 mL). The pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.5 with diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) and stirred for 2 h. Then 0.5 eq. of DOTA(OtBu)3OPFP was added and the pH was increased to 6.5. Again after stirring for 30 min, another portion of DOTA(OtBu)3OPFP (0.5 eq.) was added and the pH was increased to 6.5. The same process was repeated after another 30 min. Finally, another 0.5 eq. of DOTA(OtBu)3OPFP was added and the pH maintained at 6.5. The reaction mixture stirred for another hour and was monitored by LC-MS using method 3. Each of the three reaction mixtures was purified separately by preparative HPLC using method 1. All three products eluted from the column at approximately 60 – 61% B with a retention time of 18.1 min for PD-Pep1-PD, 17.6 min for PD-Pep2-PD and 18.0 min for PD-Pep3-PD. The fractions were collected and lyophilized to give product as a white powder. PD-Pep1-PD: Molecular weight for C126H193ClN22O32S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1313.7 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1314.1. PD-Pep2-PD: Molecular weight for C127H196ClN25O29S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1318.2 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1318.7. PD-Pep3-PD: Molecular weight for C130H195ClN24O30S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1336.7 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1337.2.

DOTA(OH)3-Pep-DOTA(OH)3 (D-Pep(n)-D)

In three separate reaction vessels, each PD-Pep(n)-PD was deprotected separately in a 1 mL solution of TFA, methanesulfonic acid, 1-dodecanethiol and H2O (92:3:3:2). Each reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hr. Cold diethylether was added to precipitate a solid, the mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was removed. The solid was washed with ether and dried to give product as a white solid. D-Pep1-D: Molecular weight for C102H145ClN22O32S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1145.5 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1145.9. D-Pep2-D: Molecular weight for C103H148ClN25O29S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1150.0 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1150.1. D-Pep3-D: Molecular weight for C109H153ClN24O30S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1168.5 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1168.6.

Cu-DOTA(OH)3-Pep-Cu-DOTA(OH)3 (FBP(n))

In separate reaction vessels each D-Pep(n)-D was dissolved in ~1 mL of 10 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc), pH 5.5. The concentration of the stock solution was approximated from the absorbance at 280 nm in comparison with the known extinction coefficient of EP-2104R (ε =5700 M−1 cm−1). The D-Pep(n)-D solutions received a 2.2 fold excess of CuSO4 and were stirred for 1 hr at room temperature. To the mixture was then added one equivalent of diethylenetriamine (dien) to coordinate any excess Cu2+ before purifying by HPLC. Each reaction mixture was purified separately by using a reverse phase C18 analytical column on Agilent 1100 HPLC and eluted using method 2. The fractions were collected, lyophilized, and then re-dissolved in water where the final concentration of FBP(n) was determined using ICP-MS. The masses of all three products were confirmed by ESI-MS with the expected isotopic ratios. FBP1 (99% purity): Molecular weight for C102H141ClCu2N22O32S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1207.0 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1207.3. FBP2 (98% purity): Molecular weight for C103H144ClCu2N25O29S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1122.6 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1211.9. FBP3 (100% purity): Molecular weight for C109H149ClCu2N24O30S2. MS (ESI): calc: 1230.0 [(M + 2H) /2]2+; found: 1230.4.

Preparation of 64Cu-Labeled Fibrin Binding Probes (FBP(n))

The radiolabeled probes were synthesized by first reacting each D-Pep(n)-D with 1.8 equiv of non-radioactive 63,65CuSO4. The reaction was monitored by LC-MS using method 3. A solution of this material ranging in concentration from approximately 50 – 250 µM was prepared in 10 mM NaOAc solution (pH 5.5). 150 µL of the 63,65Cu-D-Pep(n)-D complex solution was combined with a 64CuCl2 (1 mCi) solution (0.4 mL) in 10 mM NaOAc solution (pH 5.5), and stirred at 50 °C for 1 hr. The radiolabeling was monitored by radio-HPLC using method 2. If the reaction was not complete as judged by the appearance of unreacted 64Cu2+, then 50 µL of the 63,65Cu-D-Pep(n)-D complex solution was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for another 30 min at 50 °C. This procedure was repeated until no free 64Cu2+ was visible. The mixture then received one equiv. of dien (based on D-Pep(n)-D) and was stirred for 15 min to coordinate any excess 64Cu2+ before purifying. Each reaction mixture was purified separately using a C18 Sep-Pak column. The Sep-Pak column was first washed with EtOH (6 × 5mL) and then equilibrated with H2O (6 × 5mL). After loading the reaction mixture onto the Sep-Pak column, 64Cu-dien was first eluted with H2O (6 × 3mL) before the probes were eluted with a 1:1 mixture of EtOH:H2O (3 × 1 mL). The EtOH:H2O fractions were combined, the volume was reduced by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, and the radio-labeled FBP(n) was diluted in saline before injection into animals. The radiochemical purity (RCP) in all cases was ≥98%.

Determination of Ki

Fibrin is an insoluble polymer. We have previously shown that these peptides bind both to fibrin and a soluble proteolytic fragment of fibrin termed DD(E).23 The affinity of the peptides and probes in this study was assessed using a DD(E) fluorescence polarization displacement assay that was described previously.23 The displacement of a tetramethylrhodamine labeled peptide (TRITC-Tn6) from DD(E) by a non-fluorescent peptide or probe, Pep(n) or FBP(n), was detected by observing the corresponding change in fluorescence anisotropy. The Kd of the TRITC-Tn6 probe was determined by titrating it with the DD(E) protein and fitting the resultant fluorescence data as described previously.23 This experiment was performed at room temperature using a probe concentration of 0.1 µM in the following assay buffer: Tris base (50 mM), NaCl (100 mM), CaCl2 (2 mM), Triton X-100 (0.01%), pH = 7.8. The anisotropy measurements were made using a TECAN Infinity F200 Pro plate reader equipped with the appropriate filter set for tetramethylrhodamine (ex 535 nm / em 590 nm).

A series of Pep(n) or FBP(n) solutions were prepared through serial dilution. These solutions were then added to a mixture of the DD(E) protein and TRITC-Tn6 peptide. The final concentrations of protein and fluorescent probe used in these experiments were 2 µM and 0.1 µM, respectively. All measurements were performed at room temperature in a 384-well plate from Greiner Bio One. The inhibition constants, Ki of Pep(n) or FBP(n) were then calculated using least-squares regression and the known Kd of the fluorescent probe, as described previously.23

Animal Model

All experiments were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care. Adult male Wistar rats (350–400 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized by isoflurane (4–5% for induction, 1–2% for maintanance; in 30% oxygen – 70% nitrous oxide) or chloral hydrate and were kept under anesthesia throughout the experimental period. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37.5 °C by homeothermic blanket. The right femoral vein was cannulated for contrast agent injection. The right femoral artery was cannulated for blood sampling. A well established crush injury model was used to induce thrombosis in the carotid artery. Intramural thrombus was produced by crushing the right common carotid artery with hemostat clamps for 5 min. Probes were injected within 20 min of thrombus formation. Animals were sacrificed 2 h post-injection for tissue harvest.

Biodistribution Protocol

Male Wistar rats (350 – 400g) (n=6 for all probes) were anesthetized with isoflurane (1 – 2% in 70% N2O and 30% O2) or chloral hydrate, and body temperature was kept at 37.5°C. After surgery to induce thrombosis in the right carotid artery, the femoral vein was cannulated for intravenous delivery PET agent. Each rat was injected with approximately 0.3 – 0.4 mL and 200 – 400 µCi of the dose solution. This relatively high radiochemical dose was needed to insure that there was measurable activity in the clot and contralateral vessel, both of which weighed less than 10 mg. The total activity injected was calculated by subtracting the activity in the syringe before injection from the activity remaining in the syringe after injection as measured on a dose calibrator (Capintec CRC-25PET). After probe injection, serial blood draws were collected from the femoral artery at 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min post-injection into EDTA blood tubes. Blood was weighted and radioactivity in the blood was measured on a gamma counter (Packard, CobraII Auto gamma) to assess clearance of total 64Cu. Animals were euthanized two hours post injection and the organ distribution of 64Cu was quantified ex vivo. The thrombus (located in the right carotid artery), the contralateral carotid artery, blood, urine, intraabdominal organs, brain, left rectus femoris muscle and left femur bone were collected from all animals. The tissues were weighed, and radioactivity in each tissue was measured on a gamma counter, along with a weighed aliquot of the injected dose solution. The radioactivity in each tissue was reported as percent injected dose per gram (%ID/g) which was calculated by dividing the counts of 64Cu per gram of tissue by the total counts of the injected dose. The right and left carotid arteries were further analyzed by autoradiography using a multi-purpose film and a Perkin Elmer Cyclone Plus Storage Phosphor system. For biodistribution data, differences between groups (thrombus vs plasma, etc) were compared using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Uncertainties are expressed as standard error of the mean.

Functional Fibrin Binding Assay

Human fibrinogen (American Diagnostica) was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM sodium citrate (TBS·citrate) prior to use. The fibrinogen concentration was adjusted to 5 mg/mL (based on the absorbance at 280nm and ε280 = 1.512 Lg−1cm−1), and CaCl2 was added (7 mM). The fibrinogen solution (50 µL) was dispensed into the wells of a 96-well polystyrene microplate (Immulon-II). A solution (50 µL) of human thrombin (2 U/mL) in TBS was added to each well to clot the fibrinogen and to yield a final fibrin concentration close to 2.5 mg/mL (7.3 µM based on fibrinogen MWt = 340kDa). The plates were incubated at 37 °C and evaporated to dryness overnight.27

Blood tubes, containing blood collected at 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min post probe injection, were centrifuged (2000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C) to separate plasma. Blood plasma was then incubated in fibrin immobilized wells as well as in empty wells of the microtiter plate, and the plate was incubated for 2 h at RT. The plate was sealed with tape to prevent evaporation and agitated at 300 rpm on a shaker. After incubation, the counts in the supernatant in both the fibrin-containing and empty wells were measured on a gamma counter and divided by the weight of plasma to determine the concentration of unbound probe, [unbound], and total probe, [total], respectively. The amount of 64Cu containing species bound to fibrin, [bound], was calculated from [bound] = [total] − [unbound]. As a positive control, an aliquot of the dose was spiked into blood plasma and used to estimate the total possible fibrin binding by each FBP(n) in the assay (% bound at t=0). The amount of functional probe in the blood at time t was determined by taking the ratio of the % bound to fibrin at time t compared to the % bound at t=0, and multiplying this ratio by the measured total 64Cu %ID/g in the blood.

Urine analysis

Male Wistar rats (n=2) were used to evaluate the metabolic stability of the FBP(n). Each rat was injected with approximately 0.3 – 0.4 mL and 200 – 400 µCi of the dose solution. The total activity injected was calculated by subtracting the activity in the syringe before injection from the activity remaining in the syringe after injection as measured on a dose calibrator. Urine was collected at 120 min, filtered through a 5 µm Millex-LG filter, and analyzed by radio-HPLC (method 2).

MR/PET Imaging

PET data were acquired using the BrainPET, a MR-compatible PET scanner that operates inside of a Magnetom TIM Trio 3T MRI (Siemens), as described previously.29 Animals were imaged in a specially designed acrylic holder built in-house. The PET emission data were acquired in 3D list mode format and binned into sinograms for fast reconstruction.50 The data were reconstructed using a 3D algorithm (OS-OSEM: Ordinary Poisson Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization) with 16 subsets and six iterations, including corrections for variable detector efficiency, photon attenuation from matter, random51 and scattered52 coincidences. In order to correct for the animal’s photon attenuation, first PET images only corrected for detector efficiency were reconstructed. These images were then segmented into tissue and air using empirical determined thresholds and morphologic functions. The linear attenuation coefficient of water for 511 keV photons, 0.096 cm-1, was assigned to all tissue voxels while all air voxels were set to 0. The attenuation maps were then combined with the MR transmit coil attenuation map (derived from CT) and attenuation correction factors were generated in sinogram space. The PET data were reconstructed into 153 256×256 slices (1.25×1.25×1.25 mm3) where each voxel represented the radiotracer concentration in Bq/ml.

MR imaging was performed using the BrainPET’s circularly-polarized transmit coil in conjunction with a home built surface receive coil. 3D gradient echo T1-weighted Time-of-Flight (TOF) MR angiography sequences were performed with an echo time of 5.53 ms, repetition time of 13 ms, flip angle of 18°, field of view = 8.5 × 8.5 cm, bandwidth = 140 Hz/pixel, one average, acquisition time = 4.9 min. Time-of-Flight data was reconstructed into 124 256×256 matrices with an in-plane pixel spacing of 0.332 × 0.332 mm2 and a slice thickness of 0.300 mm. Time-of-flight data was collected before and after the probe’s injection. For anatomical imaging a 3D VIBE sequence was performed with an echo time of 4.8 ms, repetition time of 20 ms, flip angle of 12°, field of view = 10 × 20 cm, bandwidth = 130 Hz/pixel, one average, acquisition time = 3.6 min. The anatomical data consisted of 104 256×128 matrices with an in-plane resolution of 0.7813×0.7813 mm2 and slice thickness of 0.8 mm.

MR and PET data were coregistered with a rigid body transformation using the Vinci software (Max Planck Institute, http://www.nf.mpg.de/vinci3/). First, the VIBE was coregistered to the PET using a normalized mutual information algorithm. Then the higher resolution TOF data was coregistered to the VIBE image in PET space.

For the imaging studies, first baseline MR images were acquired and then the blood pool MR contrast agent Gd-DTPA-BSA (GdDTPA covalently attached to bovine serum albumin)49 was administered i.v. (50 µmol Gd/kg), and the MR scans were repeated. After the Gd-DTPA-BSA was injected, the PET probe was administered i.v. and PET data was acquired for 90 minutes.

RESULTS

Synthesis of Fibrin Binding Probes FBP1, FBP2, FBP3

The fibrin binding probes FBP1, FBP2, and FBP3 were synthesized using the general route shown in Scheme 1. DOTA(t-butyl)3-OH was directly coupled to the N- and C- termini using the PFP ester in DMF in the presence of DIPEA. Intermediates were purified by HPLC and characterized by LC-MS. We found that complexation of D-Pep(n)-D with 64Cu2+ resulted in multiple HPLC species when analyzed using a pH 6.8 ammonium acetate method. This was due to labeling at the C-terminus, N-terminus, as well as complexation of adventitious metals. To eliminate this analytical ambiguity, fibrin binding probes (FBP(n)) were synthesized by first reacting D-Pep(n)-D with 1.8 equiv of non-radioactive CuSO4 before radiolabeling with 64Cu. Labeling with 64Cu now results in a probe where both chelators are coordinated by copper. For the DD(E) binding studies, D-Pep(n)-D was chelated with 2 equiv of non-radioactive CuSO4 and purified by HPLC to give FBP(n). The purity of the non-radioactive FBP(n) was ≥98%.

Scheme 1.

General synthetic protocol for the synthesis of fibrin-binding PET probes FBP1, FBP2 and FBP3.

Radiochemistry

Radiolabeling with 64CuCl2 was carried out in NaOAc solution buffered to pH 5.5. After stirring at 50 °C for 1 h, the solution was removed from heat and stirred for 30 min with one equiv of dien to scavenge any unchelated 64Cu, and to remove any copper weakly coordinated to the peptide backbone itself. Excess dien and 64Cu(dien)2+ were removed from the probes using a C18 Sep-Pak. The radiochemical purity of the final solution was ≥98% as determined by radio-HPLC. The specific activity of the three probes ranged from 10 to 130 µCi/nmol.

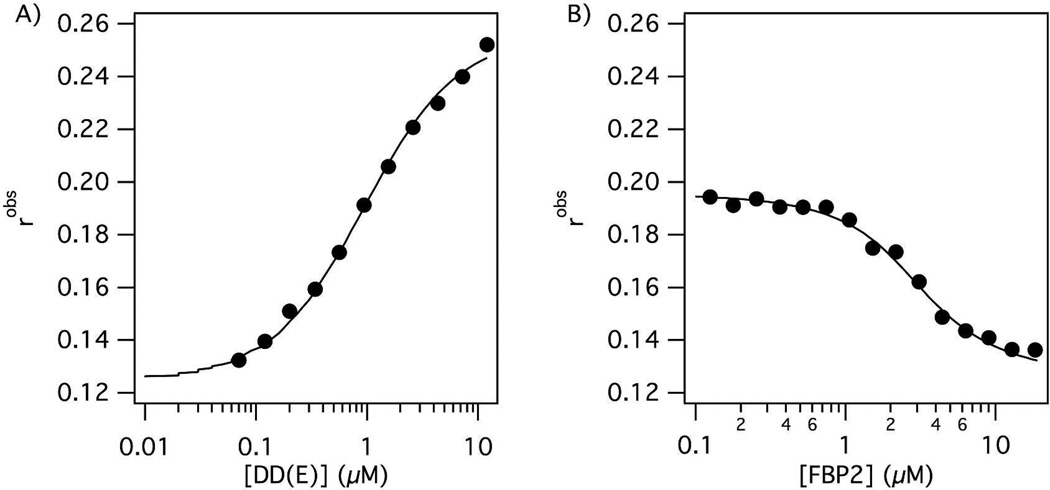

Fibrin Binding Affinity

For our binding studies, we used a soluble proteolytic fragment of fibrin called DD(E), which served as a fibrin surrogate. The fibrin affinities for the probes were determined by competitive displacement of a fluorescently labeled peptide (TRITC-Tn6), which can be followed by fluorescence anisotropy. The Kd of the TRITC-Tn6 probe was first measured by titrating it with DD(E) (Figure 1, panel a). The value was determined to be 0.92 ± 0.03 µM. The competitive inhibition constants (Ki) of the fibrin-binding probes, FBP(n), were then determined by generating a displacement curve (Figure 1, panel b), where the anisotropy of the TRITC-Tn6 probe was plotted as a function of competitor peptide concentration. The concentrations of DD(E) and TRITC-Tn6 used in these experiments were 2 µM and 0.1 µM, respectively. As a comparison, we also measured the affinity of the precursor peptides under the same reaction conditions. Fibrin-binding peptides and probes were used at a concentration range of ~ 0.1 – 18 µM. The results of this competitive assay are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

A) Binding curve of TRITC-Tn6 peptide (0.1 µM) to DD(E) protein fragment. The observed fluorescence anisotropy increases as the concentration of free probe decreases. B) The displacement of TRITC-Tn6 peptide (0.2 µM) from DD(E) (2 µM) by a competitor peptide (FBP2) results in a decrease in observed fluorescence anisotropy which is used to calculate the inhibition constant Ki.

Table 1.

Ki values (nM) determined for fibrin binding probes and peptides through the competitive displacement of a TRITC-Tn6 peptide from DD(E). Assay error is estimated at ±20% based on replicate studies with EP-2104R.

| FBP1 | FBP2 | FBP3 | Pep1 | Pep2 | Pep3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (nM) | 290 | 380 | 320 | 130 | 140 | 160 |

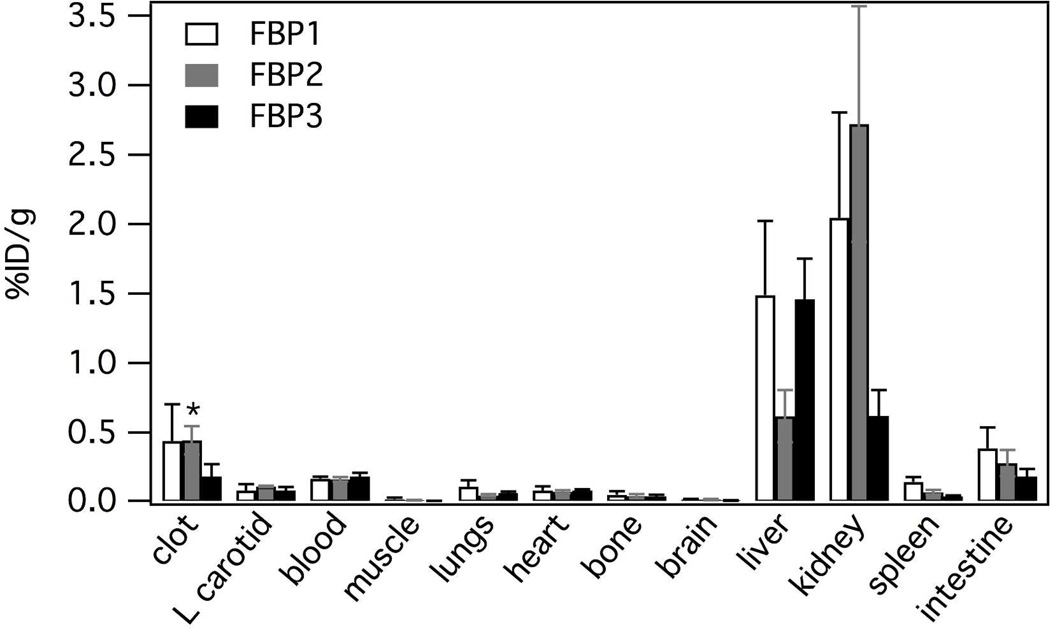

Biodistribution

Radiolabeled FBP(n) probes were investigated in a rat model of arterial thrombosis (n=6). Figure 2 and Table 2 compares the biodistribution of all three radiolabeled probes as % ID/g at 120 min. For all three probes over 70% of the activity was excreted from the animals at 120 min post injection. For FBP1 and FBP2 the kidney had the highest uptake at 120 min post probe injection followed by the liver, while for FBP3, the opposite was true. FBP2 shows the lowest liver accumulation and FBP3 had the lowest kidney uptake of all three probes.

Figure 2.

Biodistribution for FBP1, FBP2 and FBP3 (n = 6) in a rat model of arterial thrombosis at 120 min post probe injection. Error bars = SEM. * activity in the clot following FBP2 injection was significantly higher than in left carotid, blood, muscle, brain, bone, heart, spleen or lungs (p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Biodistribution data in %ID/g for FBP1, FBP2 and FBP3 (n = 6), shown in Figure 2, in a rat model of arterial thrombosis at 120 min post probe injection. Uncertainty is represented as standard error of the mean.

| FBP1 | FBP2 | FBP3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| clot | 0.440 ± 0.264 | 0.445 ± 0.102 | 0.183 ± 0.088 |

| left carotid | 0.083 ± 0.046 | 0.113 ± 0.005 | 0.084 ± 0.024 |

| blood | 0.168 ± 0.015 | 0.164 ± 0.016 | 0.184 ± 0.026 |

| muscle | 0.019 ± 0.011 | 0.012 ± 0.003 | 0.009 ± 0.001 |

| lungs | 0.109 ± 0.047 | 0.048 ± 0.010 | 0.066 ± 0.008 |

| heart | 0.082 ± 0.031 | 0.074 ± 0.011 | 0.082 ± 0.010 |

| bone | 0.052 ± 0.025 | 0.043 ± 0.015 | 0.041 ± 0.011 |

| brain | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.017 ± 0.004 | 0.011 ± 0.003 |

| liver | 1.489 ± 0.533 | 0.617 ± 0.187 | 1.459 ± 0.292 |

| kidney | 2.046 ± 0.757 | 2.722 ± 0.848 | 0.621 ± 0.186 |

| spleen | 0.145 ± 0.035 | 0.071 ± 0.016 | 0.040 ± 0.006 |

| intestine | 0.387 ± 0.151 | 0.278 ± 0.095 | 0.184 ± 0.053 |

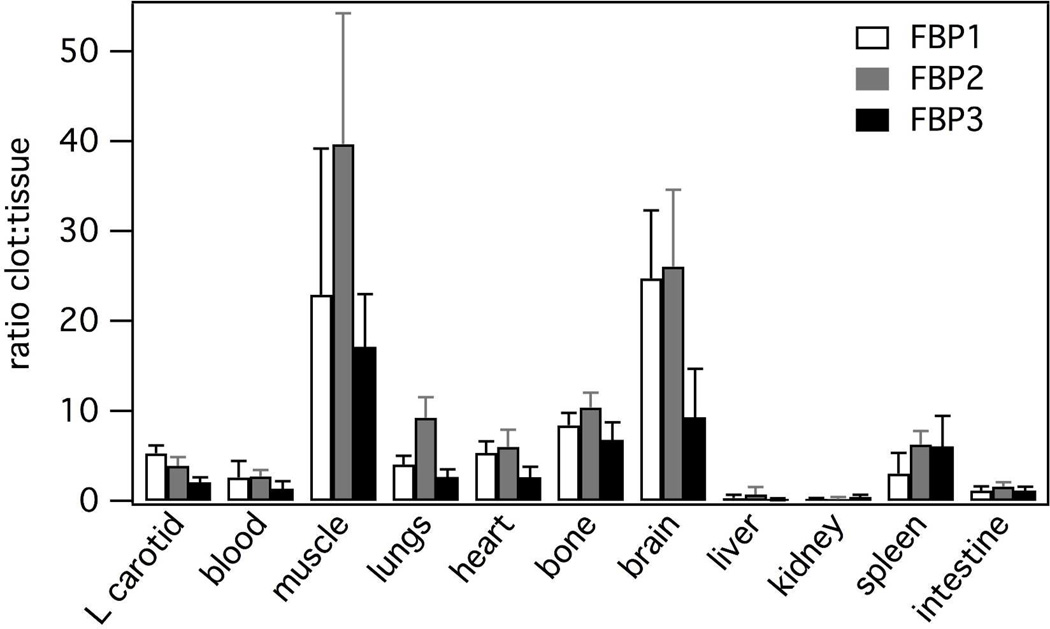

For FBP2 activity in the clot was significantly higher than in contra, blood, muscle, brain, bone, heart, or lungs (p < 0.0001). For FBP1, although the mean %ID/g in the clot was similar to FBP2, the concentration of FBP1 in the clot was not significantly higher than in other tissues. For both FBP1 and FBP2, on an individual animal basis, we always observed a higher concentration of activity in the clot than in the contralateral vessel, blood, muscle, brain, bone, heart, or lungs. For these two probes the thrombus had 4-fold or higher activity than the contralateral vessel, heart, lungs, brain, muscle or bone (Figure 3 and Table 2). The thrombus uptake of FBP1 and FBP2 was also > 2.5-fold higher than the blood. However for FBP3, the 64Cu concentration in thrombus was only 2-fold higher than the contralateral vessel, and there was no difference between the 64Cu concentration in the blood and the thrombus.

Figure 3.

Clot:tissue ratios at 120 min post injection for FBP1, FBP2 and FBP3 (n = 6) indicating the high clot:background for FBP1 and FBP2. Error bars = SEM.

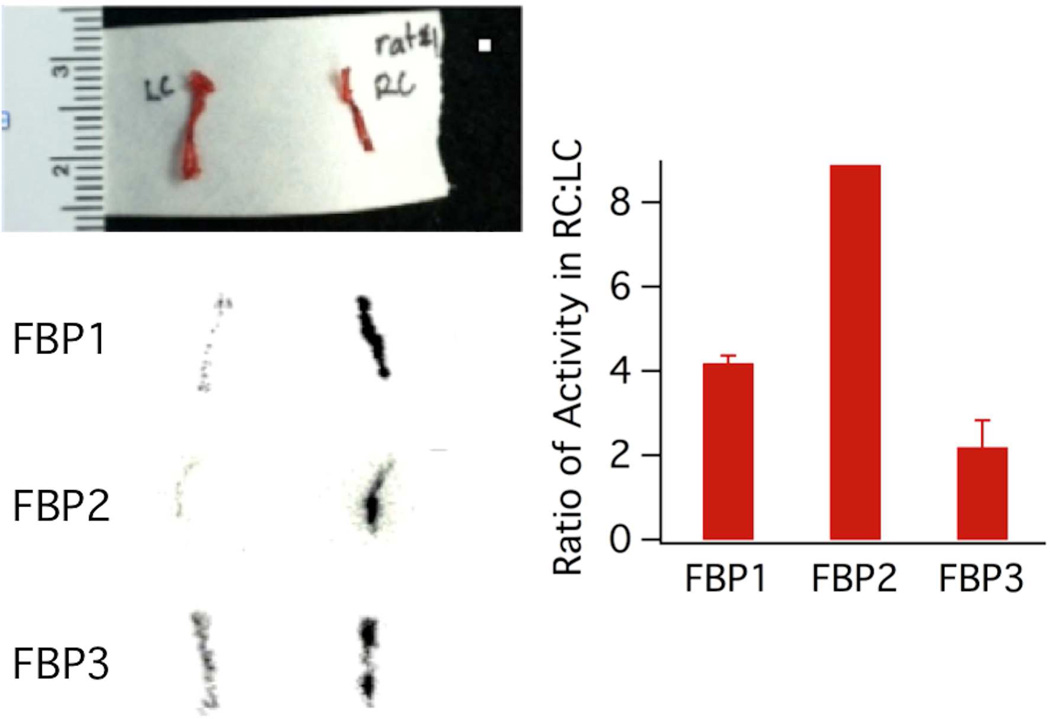

We performed ex vivo autoradiography on the right carotid (RC) and left carotid (LC) arteries in a subset of the rats. Autoradiography of the right carotid and left carotid arteries showed a hyperintense region in the right carotid segment corresponding to the location where the artery was crushed (Figure 4). As shown by the autoradiograph images and the bar graph in Figure 4, the right carotid image is 4.2 times, 8.9 times, and 2.2 times more intense than the LC image for FBP1, FBP2, and FBP3 respectively. These results agree with our biodistribution data with respect to the fact that FBP3 has the lowest clot uptake in comparison to the two other probes.

Figure 4.

Top left: Photograph of excised left (LC) and right carotid (RC) arteries. Bottom left: autoradiography images of arteries excised 120 min following injection of FBP1, FBP2, or FBP3; arterial thrombosis was induced in the RC. Right: bar graph of the ratio of activity in the RC:LC for each image. Error bars = standard deviation.

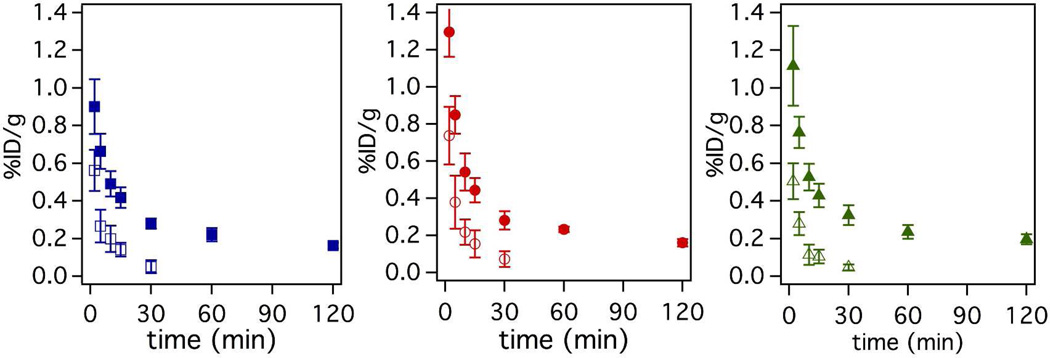

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Serial blood draws taken from 0 – 120 min post probe injection indicated that the activity cleared quickly in the first 30 min and more slowly from 30 – 120 min leaving residual activity in the blood for all probes as shown by the solid symbols in Figure 5. To estimate the amount of intact probe remaining in the blood at a given time point, we performed a functional assay to assess the fibrin binding capacity of the 64Cu-containing species. This was done by incubating blood plasma with immobilized fibrin in a microtiter plate to approximate the amount of functional probe in each serial blood draw. The fraction of probe able to bind to fibrin was compared to the fraction bound of pure probe and then multiplied by the activity in whole blood for each time point to estimate the amount of functional probe. As shown in Figure 5 (solid symbols), residual activity persists in the blood even after 120 min. The functional assay indicates that the activity in the blood represents a fraction of intact probe and that the fraction of intact probe decreases dramatically over the course of the study (Figure 5, open symbols). The functional assay results also show that FBP2 is the most metabolically stable probe followed by FBP1 and FBP3. Functional FBP3 was cleared at a much faster rate than functional FBP1 and FBP2. For instance at 10 minutes post injection only 22% of total activity was intact FBP3 compared to 40% intact for both FBP1 and FBP2.

Figure 5.

Pharmacokinetic data showing mean (n=6) blood clearance of FBP1 (squares), FBP2 (circles) and FBP3 (triangles). Solid symbols indicate total 64Cu activity in the blood, while open symbols indicate functional (intact) probe. Functional is defined as the ability of the probe to bind fibrin in a plate-based assay. Error bars = SEM.

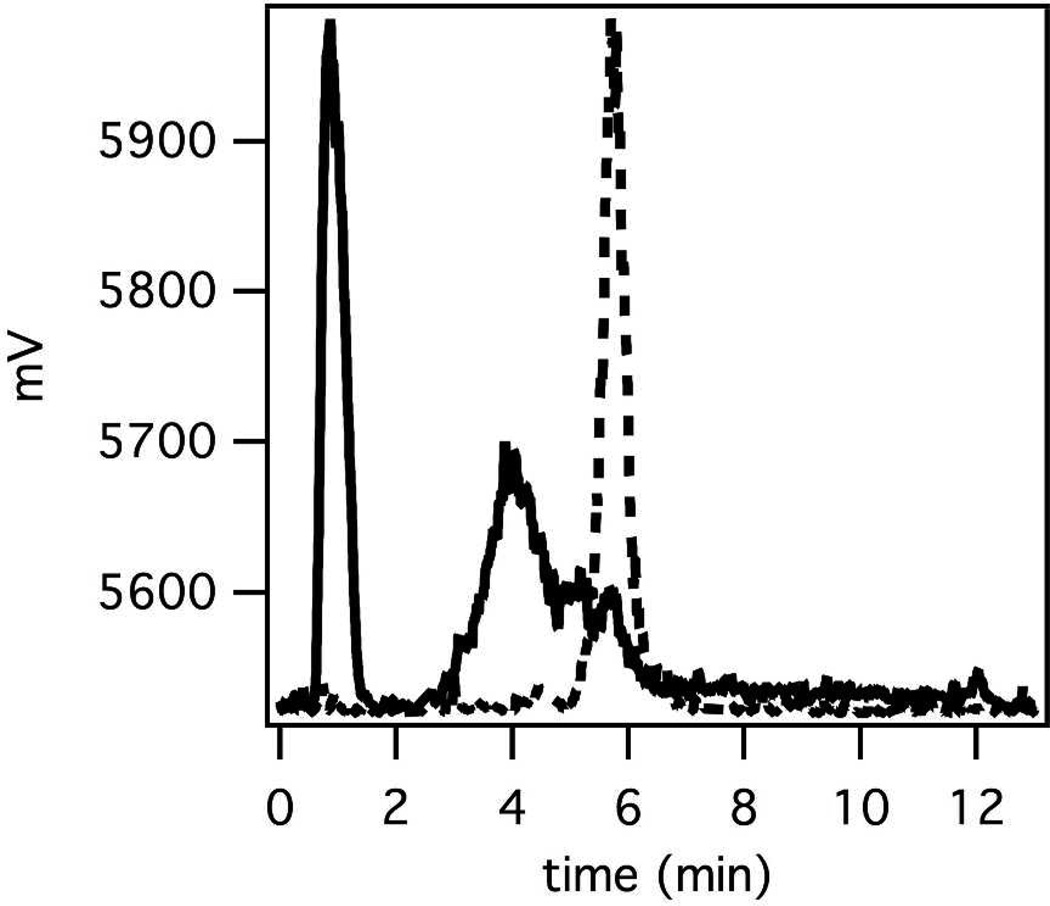

Metabolic Properties

Figure 6 shows representative radio-HPLC chromatograms of FBP2 in saline pre-injection and in urine 120 min post-injection. For all three probes the radio-HPLC analysis of the urine collected at 120 min post probe injection shows metabolites, and little to no measurable 64Cu activity in the urine is from intact probe. The identification of these metabolites and their properties has not been further studied.

Figure 6.

Representative radio-HPLC traces of intact FBP2 (dashed line) and that of urine (solid line) collected at 120 min post probe injection.

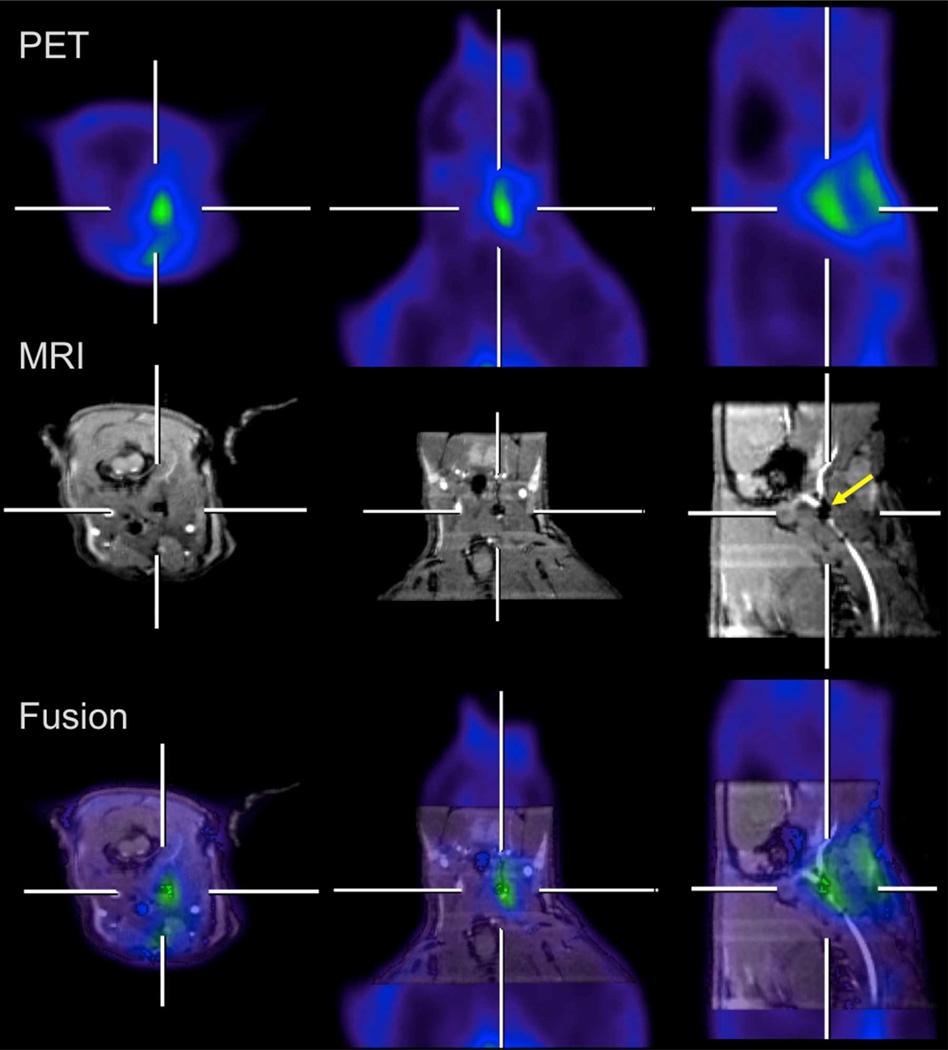

MR-PET Imaging

Figure 7 shows MR-PET images of a thrombus-bearing rat at 60 min after administration of FBP2. A blood pool agent, GdDTPA-BSA,49 was used to visualize the vascular tree on MRI. The images shown are three orthogonal views that bisect the thrombus. The MR angiography images show an occlusion in the right carotid artery (a signal void that is highlighted by a yellow arrow) at the site of crush injury, and this vessel occlusion corresponds to the hyperintense signal shown in the PET images. Fused images clearly show that the hyperintense signal observed with PET overlays with the occlusion in the MR images. Additional increased PET activity is seen superficially at the surgical incision site. Similar images were obtained using FBP1 (data not shown). The crush injury site was clearly visualized indicating FBP1 and FBP2 are useful for imaging thrombus.

Figure 7.

Hybrid MR-PET imaging of FBP2 in a rat model of arterial thrombosis. The crosshairs show where each plane bisects the site of injury in the right carotid (RC) artery. Top: PET images; middle: GdDTPA-BSA enhanced MRI provides positive image contrast to the blood vessels and demonstrate an occlusion in the RC (arrow); bottom: fused MR (grayscale) – PET (color) images showing localization of PET signal to the occlusion in the RC. Additional PET activity is seen superficially at the surgical incision site, presumably due to clotting at the site of tissue injury.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we present the synthesis and evaluation of FBP1, FBP2, and FBP3 as fibrin-targeted PET probes for detecting thrombus in a rat model of arterial thrombosis. For our PET probes, we chose to utilize three previously reported fibrin-specific peptides, each reported as having a high affinity and specificity for fibrin.27, 39, 47, 48 We reasoned that although these three peptides all showed similar high affinity for fibrin, that it was likely that their in vivo efficacy as PET probes would vary due to off-target accumulation or metabolism. We directly compared these peptides conjugated with 64Cu-DOTA with respect to their in vitro fibrin binding affinity and their in vivo thrombus uptake, biodistribution, metabolic stability and imaging efficacy. 64Cu is an ideal PET reporter for our purposes due to fact that it can be produced with high specific activity53 and its half-life of 12.7 h allows for ease of handling during radiochemical syntheses. DOTA was chosen as a chelate because it forms a highly stable 64Cu complex54–56 and is a relatively inexpensive reagent.

Each cyclic peptide contains eleven amino acids, in which six of the amino acids are the same in each peptide. It has previously been shown that retention of these six amino acids and incorporation of a disulfide bond between the cysteine residues are essential for maintaining the fibrin-binding integrity of the peptides.57 A xylenediamine moiety was utilized to introduce a primary amine at the C-terminus and DOTA was coupled to both the C- and N- termini through an amide linkage. We chose to derivatize the peptides in this way because our previous experience with fibrin-targeted peptides has shown that derivatization at both the C- and N-terminus has minimal effect on fibrin-binding ability and protects the peptide from exopeptidase degradation.58

The fibrin affinities of the probes: FBP1, FBP2 and FBP3 and the precursor peptides: Pep1, Pep2 and Pep3 were assessed by measuring the displacement of a fluorescent peptide from the soluble fibrin fragment DD(E). This protein fragment serves as a useful surrogate of the fibrin polymer since it contains the same binding site recognized by these peptides but is fully soluble in aqueous buffers. As expected, the three peptides chosen all exhibited similar and high nanomolar affinity for DD(E). The incorporation of a DOTA moiety at the C- and N- termini of the precursor peptides did not substantially affect the fibrin affinity of the probes. The inhibition constants of the probes, indicate that the affinities for DD(E) are similar and comparable to that of the established MRI probe EP-2104R with a value of 0.2 µM.23

Although all three probes displayed similar fibrin affinity after being derivatized, their fibrin affinity did not always correlate with in vivo efficacy. For example, the biodistribution data for FBP1 and FBP2 showed ~4 fold or higher activity in the thrombus than in any tissue in the head or thorax, whereas the thrombus uptake for FBP3 did not show the same promise. These findings were confirmed by autoradiography studies comparing the right carotid segment containing the thrombus to the control left carotid artery where FBP1 and FBP2 both showed significantly higher activity in the thrombus containing vessel while FBP3 uptake was similar in both vessels. From these results, we determined that FBP3 would not be optimal for thrombus imaging. On the other hand, the results of our biodistribution and autoradiography studies demonstrate that FBP1 and FBP2 would be ideal for imaging thrombus. Our imaging data using simultaneous MR-PET confirmed that these PET probes are indeed very effective at achieving accurate clot detection. Combining the high spatial resolution of MRI with the molecular specificity of PET allowed us to localize the thrombus precisely within the carotid artery.

The differences in efficacy between the probes may be attributed to metabolic stability with respect to peptide degradation and 64Cu release. Our pharmacokinetic data showed that the 64Cu blood clearance profile is very similar for all three probes and is not as expected for small probes with low protein binding. There is a rapid clearance of activity from the blood in the first 30 min, which then slows over the next 90 min leaving residual activity in the blood after 120 min. We speculate that the slow-clearing component of radioactivity is due to 64Cu that has dissociated from the chelator and is now bound to plasma proteins. Although our Cu2+-chelate, DOTA, has a high affinity for 64Cu, it is not ideal, and 64Cu release from DOTA has been reported.59, 60

The results of our ex vivo binding assay confirmed that the slow clearing activity in the blood is not due to intact probe. We found that over time, the amount of functional fibrin-binding probe decreased in all cases. Urine analysis at 120 min reveals minimal intact probe and confirms the presence of low molecular weight metabolites. In comparing the three probes, FBP3 shows the least metabolic stability and in turn the least amount of functional probe at all time points over the 120 min experimental time course. At any given time point the amount of functional FBP3 in blood is a fraction of what is available for FBP1 or FBP2. Therefore, the slower metabolism of FBP1 and FBP2 leaves more functional probe circulating in the blood and allows the potential for greater accumulation in the clot. These results demonstrate why FBP3 performed so poorly in clot uptake measurements despite showing high affinity for fibrin in vitro.

Although our three probes are very similar the subtle differences in peptide sequence had significant effects on metabolism and in turn in vivo efficacy. Despite some metabolism, our best probes, FBP1 and FBP2, proved to be very effective for thrombus detection. Our future work is aimed at further improving our target:background ratio by reducing the metabolism of these two probes. We plan to enhance our already effective probes by modifying the charge, chelates, and linkers in an effort to evaluate the affects on in vivo metabolism.

There are other nuclear medicine approaches for imaging fibrin. Past approaches have relied primarily on antibody or antibody fragment approaches to targeting.61–65 The most promising of these approaches is a Tc-99m radiolabelled humanized monoclonal antibody fragment specific for the D-dimer region of cross-linked fibrin to detect acute venous thromboembolism, that is currently being evaluated in clinical trials.32, 66, 67 It is not possible to compare our probes to these other approaches, since other researchers have focused on the venous system and utilized different animal models than the rat arterial injury model used in this work. Possible benefits of our probes are: 1) the higher spatial resolution of PET compared to SPECT; 2) the combination of PET with either CT or MRI to provide detailed vascular anatomy; and 3) the simple chemical structure of our short peptide-based probes compared to antibodies which may provide benefits of cost of production and pharmacokinetics.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we conjugated 64Cu-DOTA to three fibrin-binding peptides for evaluation as thrombus-targeted PET probes. We have shown that all three probes maintained fibrin affinity after being derivatized with 64Cu-DOTA, however for one of our probes, FBP3, in vitro affinity studies did not correspond with in vivo efficacy studies. These differences were traced to metabolic stability with respect to peptide degradation and/or copper release. The other two probes, FBP1 and FBP2, showed enhanced metabolic stability and very promising results in vivo with a 4-fold or higher thrombus:background ratio. In addition, FBP1 and FBP2 showed accurate detection of arterial thrombus and imaging efficacy in a rat model using hybrid MR-PET imaging. Imaging and biodistribution data show that FBP1 and FBP2 are very effective PET probes for the detection of thrombus, although their metabolism, which leads to persistent residual activity in the blood after 120 min is a limitation. Future work is aimed at the judicious modification of the linker and 64Cu-chelate incorporated in these fibrin-specific probes to enable enhanced in vivo thrombus uptake and metabolic stability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by Awards R01HL109448, T32CA009502, and P41RR14075 from the National Institutes of Health. P.C. has equity in Factor 1A, LLC, the company which holds the patent rights to the peptides used in these probes.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

computed tomography

- PET

positron emission tomography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- FA

formic acid

- DOTA(tBu)3-OH

tri-tert-butyl 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetate

- PFP

pentafluorophenol

- DCM

dichloromethane

- PS-DCC

polystryrene-carbodiimide resin

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- NaOAc

sodium acetate

- dien

diethylenetriamine

- %ID/g

percent injected dose per gram tissue weight

- Pep(n)

fibrin specific peptides, n =1–3

- FBP(n)

fibrin binding probes, n=1–3

- OP-OSEM

ordinary Poisson ordered subset expectation maximization

- TOF

time of flight

- Gd-DTPA-BSA

GdDTPA covalently attached to bovine serum albumin

- RC

right carotid

- LC

left carotid

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:188–197. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet. 2012;379:1835–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris TA. SPECT imaging of pulmonary emboli with radiolabeled thrombus-specific imaging agents. Semin Nucl Med. 2010;40:474–479. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis MS, Burn JP, Sandercock PA, Bamford JM, Wade DT, Warlow CP. Long-term survival after first-ever stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1993;24:796–800. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.6.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillen T, Coshall C, Tilling K, Rudd AG, McGovern R, Wolfe CD. Cause of stroke recurrence is multifactorial: patterns, risk factors, and outcomes of stroke recurrence in the South London Stroke Register. Stroke. 2003;34:1457–1463. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072985.24967.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warfarin versus aspirin for prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation II Study. Lancet. 1994;343:687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, Levin B, Sacco RL, Furie KL, Kistler JP, Albers GW, Pettigrew LC, Adams HP, Jr, Jackson CM, Pullicino P. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1444–1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guercini F, Acciarresi M, Agnelli G, Paciaroni M. Cryptogenic stroke: time to determine aetiology. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Tullio MR, Russo C, Jin Z, Sacco RL, Mohr JP, Homma S. Aortic arch plaques and risk of recurrent stroke and death. Circulation. 2009;119:2376–2382. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.811935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Gongora-Rivera F, Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ, Amarenco P. Autopsy prevalence of intracranial atherosclerosis in patients with fatal stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1142–1147. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Gongora-Rivera F, Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ, Amarenco P. Autopsy prevalence of proximal extracranial atherosclerosis in patients with fatal stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:713–718. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overell JR, Bone I, Lees KR. Interatrial septal abnormalities and stroke: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Neurology. 2000;55:1172–1179. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amarenco P, Cohen A, Tzourio C, Bertrand B, Hommel M, Besson G, Chauvel C, Touboul PJ, Bousser MG. Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch and the risk of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1474–1479. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dressler FA, Craig WR, Castello R, Labovitz AJ. Mobile aortic atheroma and systemic emboli: efficacy of anticoagulation and influence of plaque morphology on recurrent stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrari E, Vidal R, Chevallier T, Baudouy M. Atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta and aortic debris as a marker of poor prognosis: benefit of oral anticoagulants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1317–1322. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beyer T, Freudenberg LS, Czernin J, Townsend DW. The future of hybrid imaging-part 3: PET/MR, small-animal imaging and beyond. Insights Imaging. 2011;2:235–246. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catana C, Procissi D, Wu Y, Judenhofer MS, Qi J, Pichler BJ, Jacobs RE, Cherry SR. Simultaneous in vivo positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3705–3710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711622105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlemmer HP, Pichler BJ, Schmand M, Burbar Z, Michel C, Ladebeck R, Jattke K, Townsend D, Nahmias C, Jacob PK, Heiss WD, Claussen CD. Simultaneous MR/PET imaging of the human brain: feasibility study. Radiology. 2008;248:1028–1035. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483071927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Townsend DW. Dual-modality imaging: combining anatomy and function. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:938–955. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitchler BJJ, M S, Pfannenberg C. Multimodal imaging approaches: PET/CT and PET/MRI. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;185:109–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72718-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindner JR. Molecular Imaging of Thrombus. Circulation. 2012;125:3057–3059. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciesienski KLC, P Molecular MRI of Thrombosis. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2010;4:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s12410-010-9061-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolodziej AF, Nair SA, Graham P, McMurry TJ, Ladner RC, Wescott C, Sexton DJ, Caravan P. Fibrin specific peptides derived by phage display: characterization of peptides and conjugates for imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:548–556. doi: 10.1021/bc200613e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makowski MR, Forbes SC, Blume U, Warley A, Jansen CH, Schuster A, Wiethoff AJ, Botnar RM. In vivo assessment of intraplaque and endothelial fibrin in ApoE(−/−) mice by molecular MRI. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miserus RJ, Herias MV, Prinzen L, Lobbes MB, Van Suylen RJ, Dirksen A, Hackeng TM, Heemskerk JW, van Engelshoven JM, Daemen MJ, van Zandvoort MA, Heeneman S, Kooi ME. Molecular MRI of early thrombus formation using a bimodal alpha2-antiplasmin-based contrast agent. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair SA, Kolodziej AF, Bhole G, Greenfield MT, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. Monovalent and bivalent fibrin-specific MRI contrast agents for detection of thrombus. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:4918–4921. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overoye-Chan K, Koerner S, Looby RJ, Kolodziej AF, Zech SG, Deng Q, Chasse JM, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. EP-2104R: a fibrin-specific gadolinium-based MRI contrast agent for detection of thrombus. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6025–6039. doi: 10.1021/ja800834y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uppal R, Ay I, Dai G, Kim YR, Sorensen AG, Caravan P. Molecular MRI of intracranial thrombus in a rat ischemic stroke model. Stroke. 2010;41:1271–1277. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uppal R, Catana C, Ay I, Benner T, Sorensen AG, Caravan P. Bimodal thrombus imaging: simultaneous PET/MR imaging with a fibrin-targeted dual PET/MR probe--feasibility study in rat model. Radiology. 2011;258:812–820. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Kolodziej AF, Greenfield MT, Caravan P. Heteroditopic binding of magnetic resonance contrast agents for increased relaxivity. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:2621–2624. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uppal RC, K L, Chonde DB, Loving GS, Caravan P. Discrete bimodal probes for thrombus imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10799–10808. doi: 10.1021/ja3045635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris TA, Gerometta M, Yusen RD, White RH, Douketis JD, Kaatz S, Smart RC, Macfarlane D, Ginsberg JS. Detection of pulmonary emboli with 99mTc-labeled anti-D-dimer (DI-80B3)Fab' fragments (ThromboView) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:708–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0624OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai K, Kiefer GE, Caruthers SD, Wickline SA, Lanza GM, Winter PM. Quantification of water exchange kinetics for targeted PARACEST perfluorocarbon nanoparticles. NMR Biomed. 2012;25:279–285. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarthy JR, Patel P, Botnaru I, Haghayeghi P, Weissleder R, Jaffer FA. Multimodal nanoagents for the detection of intravascular thrombi. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1251–1255. doi: 10.1021/bc9001163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan D, Caruthers SD, Hu G, Senpan A, Scott MJ, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Ligand-directed nanobialys as theranostic agent for drug delivery and manganese-based magnetic resonance imaging of vascular targets. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9186–9187. doi: 10.1021/ja801482d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan D, Caruthers SD, Senpan A, Yalaz C, Stacy AJ, Hu G, Marsh JN, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Synthesis of NanoQ, a copper-based contrast agent for high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging characterization of human thrombus. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9168–9171. doi: 10.1021/ja201918u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan D, Pramanik M, Senpan A, Yang X, Song KH, Scott MJ, Zhang H, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Wang LV, Lanza GM. Molecular photoacoustic tomography with colloidal nanobeacons. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:4170–4173. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morawski AML, G A, Wickline SA. Targeted contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Botnar RM, Perez AS, Witte S, Wiethoff AJ, Laredo J, Hamilton J, Quist W, Parsons EC, Jr, Vaidya A, Kolodziej A, Barrett JA, Graham PB, Weisskoff RM, Manning WJ, Johnstone MT. In vivo molecular imaging of acute and subacute thrombosis using a fibrin-binding magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Circulation. 2004;109:2023–2029. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127034.50006.C0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sirol M, Fuster V, Badimon JJ, Fallon JT, Moreno PR, Toussaint JF, Fayad ZA. Chronic thrombus detection with in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and a fibrin-targeted contrast agent. Circulation. 2005;112:1594–1600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.522110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spuentrup E, Buecker A, Katoh M, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC, Jr, Botnar RM, Weisskoff RM, Graham PB, Manning WJ, Gunther RW. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of coronary thrombosis and pulmonary emboli with a novel fibrin-targeted contrast agent. Circulation. 2005;111:1377–1382. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158478.29668.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spuentrup E, Katoh M, Buecker A, Fausten B, Wiethoff AJ, Wildberger JE, Haage P, Parsons EC, Jr, Botnar RM, Graham PB, Vettelschoss M, Gunther RW. Molecular MR imaging of human thrombi in a swine model of pulmonary embolism using a fibrin-specific contrast agent. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:586–595. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31804fa154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spuentrup E, Katoh M, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC, Jr, Botnar RM, Mahnken AH, Gunther RW, Buecker A. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of pulmonary emboli with a fibrin-specific contrast agent. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:494–500. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-379OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stracke CP, Katoh M, Wiethoff AJ, Parsons EC, Spangenberg P, Spuntrup E. Molecular MRI of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis using a new fibrin-specific MR contrast agent. Stroke. 2007;38:1476–1481. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.479998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spuentrup E, Botnar RM, Wiethoff AJ, Ibrahim T, Kelle S, Katoh M, Ozgun M, Nagel E, Vymazal J, Graham PB, Gunther RW, Maintz D. MR imaging of thrombi using EP-2104R, a fibrin-specific contrast agent: initial results in patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1995–2005. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vymazal J, Spuentrup E, Cardenas-Molina G, Wiethoff AJ, Hartmann MG, Caravan P, Parsons EC., Jr Thrombus imaging with fibrin-specific gadolinium-based MR contrast agent EP-2104R: results of a phase II clinical study of feasibility. Invest Radiol. 2009;44:697–704. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181b092a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koerner S, Kolodziej A, Nair S, McMurry T, Nivoroshkin A, Pratt C, Sun W, Wang X, Zhang Z, Caravan P, Uprichard A. Optimization of fibrin-binding peptides as targeting vectors for thrombus-specific MRI contrast agents. Proc. 236th ACS National Meeting; Philadelphia, PA. 2008. MEDI-403. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z, Amedio JC, Caravan P, Dumas S, Kolodziej A, McMurry TJ. Peptide-Based Multimeric Targeted Contrast Agents. 7,238,341. US Patent. 2007

- 49.Schmiedl U, Ogan M, Paajanen H, Marotti M, Crooks LE, Brito AC, Brasch RC. Albumin labeled with Gd-DTPA as an intravascular, blood pool-enhancing agent for MR imaging: biodistribution and imaging studies. Radiology. 1987;162:205–210. doi: 10.1148/radiology.162.1.3786763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong IKC, S T, Kim HK, Kim YB, Son YD, Cho ZH. Ultra fast symmetry and SIMD-based projection-backprojection (SSP) algorithm for 3-D PET image reconstruction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:789–803. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2007.892644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Byars LGS, M, Burbar Z, Jones J, Panin V, Barker WC, Liow J-S, Carson RE, Michel C. Variance reduction on randoms from coincidence histograms for the HRRT. IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Conf Rec. 2005;5:2622–2626. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson CC. New faster, image-based scatter correction for 3D PET. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2000;47:1587–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson CJG, M A, Fujibayashi Y. Chemistry of copper radionuclides and radiopharmaceutical products. Handbook of Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003:401–402. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blower BJL, J S, Zweit J. Copper radionuclides and radiopharmaceuticals in nuclear medicine. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:957–980. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reichert DEL, J S, Anderson CJ. Metal complexes as diagnostic tools. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;184:3–66. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu S. Bifunctional coupling agents for target-specific delivery of metallic radionuclides. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:1347–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uppal R, Medarova Z, Farrar CT, Dai G, Moore A, Caravan P. Molecular imaging of fibrin in a breast cancer xenograft mouse model. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:553–558. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31825dddfb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z, Kolodziej AF, Qi J, Nair SA, Wang X, Case AW, Greenfield MT, Graham PB, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. Effect of Peptide-Chelate Architecture on Metabolic Stability of Peptide-based MRI Contrast Agents. New J Chem. 2010;2010:611–616. doi: 10.1039/b9nj00787c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bass LA, Wang M, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. In vivo transchelation of copper-64 from TETA-octreotide to superoxide dismutase in rat liver. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:527–532. doi: 10.1021/bc990167l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boswell CA, Sun X, Niu W, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Rheingold AL, Anderson CJ. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1465–1474. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bosnjakovic VB, Jankovic BD, Horvat J, Cvoric J. Radiolabelled anti-human fibrin antibody: a new thrombus-detecting agent. Lancet. 1977;1:452–454. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosebrough SF, Kudryk B, Grossman ZD, McAfee JG, Subramanian G, Ritter-Hrncirik CA, Witanowski LS, Tillapaugh-Fay G. Radioimmunoimaging of venous thrombi using iodine-131 monoclonal antibody. Radiology. 1985;156:515–517. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.2.4011916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knight LC, Maurer AH, Ammar IA, Epps LA, Dean RT, Pak KY, Berger HJ. Tc-99m antifibrin Fab' fragments for imaging venous thrombi: evaluation in a canine model. Radiology. 1989;173:163–169. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.1.2781002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris TA, Marsh JJ, Konopka R, Pedersen CA, Chiles PG, Fagnani R, Hagan M, Moser KM. Antibodies against the fibrin beta-chain amino-terminus detect active canine venous thrombi. Circulation. 1997;96:3173–3179. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thakur ML, Pallela VR, Consigny PM, Rao PS, Vessileva-Belnikolovska D, Shi R. Imaging vascular thrombosis with 99mTc-labeled fibrin alpha-chain peptide. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morris TA, Marsh JJ, Chiles PG, Konopka RG, Pedersen CA, Schmidt PF, Gerometta M. Single photon emission computed tomography of pulmonary emboli and venous thrombi using anti-D-dimer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:987–993. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-735OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douketis JD, Ginsberg JS, Haley S, Julian J, Dwyer M, Levine M, Eisenberg PR, Smart R, Tsui W, White RH, Morris TA, Kaatz S, Comp PC, Crowther MA, Kearon C, Kassis J, Bates SM, Schulman S, Desjardins L, Taillefer R, Begelman SM, Gerometta M. Accuracy and safety of (99m)Tc-labeled anti-D-dimer (DI-80B3) Fab' fragments (ThromboView(R)) in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis: a phase II study. Thromb Res. 2012;130:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]