Summary

Purpose

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) resistant to treatment is common, but its neuronal correlates are not entirely understood. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine resting-state default mode network (DMN) functional connectivity in patients with treatment-resistant IGE.

Methods

Treatment-resistance was defined as continuing seizures despite an adequate dose of valproic acid (valproate, VPA). Data from 60 epilepsy patients and 38 healthy controls who underwent simultaneous EEG and resting-state fMRI were included (EEG/fMRI). Independent component analysis (ICA) and dual regression were used to quantify DMN connectivity. Confirmatory analysis using seed-based voxel correlation was performed.

Key Findings

There was a significant reduction of DMN connectivity in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy when compared to patients who were treatment-responsive and healthy controls. Connectivity was negatively correlated with duration of epilepsy.

Significance

Our findings in this large sample of patients with IGE indicate the presence of reduced DMN connectivity in IGE and show that connectivity is further reduced in treatment-resistant epilepsy. DMN connectivity may be useful as a biomarker for treatment-resistance.

Keywords: Independent Component Analysis, Seed-Based Voxel Correlation, Primary Generalized Epilepsy, Dual Regression, Resting-State Functional Connectivity, Valproic Acid

Introduction

Primary or idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) accounts for 15-30% of all epilepsy cases [Jallon & Latour, 2005; Szaflarski et al. 2010b]. Although much progress has been made in discovering the etiology of IGE, the neuronal causes of treatment-resistance remain poorly understood. The treatment armamentarium against IGE is mostly pharmacological, and a combination of one or more drugs will control seizures in more than 80% of patients [Faught, 2004]. Valproic acid (valproate, VPA) in particular is predictive of drug-resistance, with fewer than 10% of patients who fail an adequate dose of VPA achieving seizure control with any combination of other drugs [French et al. 2004; Holland et al. 2010; Szaflarski et al. 2010b]. Drug-resistant patients may undergo vagus nerve stimulation [Kostov et al. 2007; Labar et al. 1999; Ng & Devinsky, 2004] or a ketogenic diet [Groomes et al. 2011], but these therapies are better at reducing seizure frequency than they are at achieving seizure control. Surgery is contraindicated in IGE due to presumed genetic etiology and generalized seizure onset [Engel, 1993; Upchurch & Stern, 2006]. Thus, intractable IGE is characterized by uncontrolled seizures despite treatment with syndrome-appropriate AEDs.

The generalized spike and wave discharge (GSWD) is a hallmark of IGE, and its observation with EEG during “staring spells” is pathognomonic for the absence seizure [Yenjun et al. 2003]. GSWD are thought to arise, in part, from abnormal neuronal circuits [Contreras et al. 1996; Moeller et al. 2008a]. MRI, especially diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of white matter tracts, allows for non-invasive investigation of these circuits in humans. However, because the brains of patients with IGE are grossly normal [Opeskin et al. 2000], structural MRI may not be sensitive enough to detect abnormal connectivity. Using fMRI to study intrinsic, or resting-state brain connectivity provides a measure of these circuits consistent with but independent from measures of structural connectivity [Greicius et al. 2009]. There is evidence that this approach is more sensitive than DTI at detecting abnormal connectivity in IGE [Zhang et al. 2011]. Previous studies of IGE and its subpopulations have found altered resting-state functional connectivity in the default mode network (DMN) [Luo et al. 2011; McGill et al. 2012], dorsal attention network [Killory et al. 2011], and between hemispheres [Bai et al. 2011].

Simultaneous EEG/fMRI allows for temporal alignment of the fMRI hemodynamic response with electrographic features such as GSWD detected on EEG [Gotman et al. 2006]. These multimodal data are useful in the investigation of functional connectivity because analysis of the fMRI signal can be restricted to periods of normal EEG, preventing contamination of the resting-state by GSWD. The opposite is also possible, and several EEG/fMRI studies have reported on fMRI activation and deactivation associated with GSWD in IGE [Aghakhani et al. 2004; Gotman et al. 2005; Laufs et al. 2006; Moeller et al. 2008b; Szaflarski et al. 2010a; Tyvaert et al. 2009]. Deactivation occurs specifically in brain regions that coincide with the default mode network (DMN) [Aghakhani et al. 2004; Gotman et al. 2005; Laufs et al. 2006; Moeller et al. 2008b], a resting-state network thought to support consciousness [Fox et al. 2005; Raichle et al. 2001]. It is probably not a coincidence that deactivation of the DMN during GSWD coincides with transient loss of consciousness during absence seizures [Danielson et al. 2011].

Two recent resting-state studies have found that DMN connectivity is lower in patients with IGE than in healthy controls; further, in these studies, connectivity was negatively correlated with disease duration [Luo et al. 2011; McGill et al. 2012]. Although highly relevant, these existing DMN studies were limited with respect to equipment and experimental population. One study with 15 IGE patients was fMRI-only and thus could not exclude or control for the effects of GSWD on the resting-state [McGill et al. 2012]. A separate 12-patient EEG/fMRI study restricted analysis to periods of normal EEG, but all patients in this study suffered from uncontrolled seizures at the time of scanning preventing the authors from evaluating the effects of disease severity on DMN connectivity [Luo et al. 2011]. Both studies used seed-based voxel correlation to assess DMN connectivity, and we are not aware of any studies that have used independent component analysis (ICA) for this purpose. ICA and seed-based voxel correlation are both tools for detecting functional connectivity, but ICA offers superior separation of structured noise from resting-state fluctuations [Damoiseaux et al. 2006; Ma et al. 2007]. Thus, in this resting-state EEG/fMRI study we investigated DMN connectivity in a heterogenous population of 60 IGE patients and 38 healthy controls using ICA and performed confirmatory analysis using seed-based voxel correlation. Further, we examined the effect of VPA-resistance and uncontrolled seizures on DMN connectivity. We hypothesized that treatment-resistant IGE has a neuronal basis and is thus linked to an observable decrease in DMN connectivity, a putative neuronal marker for treatment-resistant IGE, when compared to treatment-responsive IGE patients and/or healthy controls.

Methods

All patients with IGE evaluated in the Cincinnati Epilepsy Center were approached for participation and enrolled prospectively irrespective of their seizure control, medication status, or demographic characteristics. Enrolled subjects fulfilled all criteria for the diagnosis of IGE based on published criteria [Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1989]. As in our previous studies, diagnosis and treatment were directed by an epilepsy specialist [Szaflarski et al. 2008]. Patients with a history of absence seizures received 24-hour ambulatory EEG to document seizure-freedom. Response to VPA was defined as seizure freedom lasting at least three months during treatment with VPA with at least one VPA level documented as therapeutic. Patients who did not achieve seizure control for three months while receiving VPA with consistently therapeutic VPA levels were considered VPA-resistant. Patients who were not treated with VPA or whose treatment with VPA lasted less than three months due to intolerable side effects were categorized as VPA-unknown. Patients who had one or more seizures in the three months leading up to scanning were categorized as having uncontrolled seizures independent of their VPA status. Most (n=9) patients with uncontrolled seizures also satisfied our criteria for VPA-resistance, but some did not either because they had never tried VPA (n=3) or because they were VPA-responsive but were not being treated in the months leading up to scanning (n=4); see Table 1.

Table 1. Subject Demographics.

Demographics of idiopathic generalized epilepsy patients, subdivided by clinical feature, and healthy controls. Mean age and duration of epilepsy at scanning (± standard deviation) are given in years. The number of medications being taken at time of scanning and number of medications that previously failed to produce seizure control are reported. Seizures- = epilepsy patients whose seizures are controlled. Seizures+ = uncontrolled seizures. VPA+ = epilepsy patients who respond to the drug valproate. VPA− = valproate resistant patients. VPA? = epilepsy patients whose response to valproate is unknown. JME = juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

| Male | Female | Age (years ± SD) | Duration (years ± SD) | # Current Drugs | # Failed Drugs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy (All) | 25 | 35 | 31.5±11.7 | 15.5±12.0 | 1.47 | 1.95 |

| Epilepsy (Seizures−) | 17 | 27 | 32.2±11.3 | 15.1±11.0 | 1.25 | 1.45 |

| Epilepsy (Seizures+) | 8 | 8 | 29.4±13.1 | 16.5±14.6 | 2.06 | 3.40 |

| Epilepsy (VPA+) | 14 | 14 | 27.5±6.7 | 13.2±7.3 | 1.18 | 1.54 |

| Epilepsy (VPA−) | 7 | 6 | 35.6±15.7 | 23.7±17.7 | 2.31 | 3.67 |

| Epilepsy (VPA?) | 4 | 15 | 34.4±13.2 | 13.2±10.9 | 1.32 | 1.47 |

| Epilepsy (JME) | 14 | 16 | 28.1±9.2 | 13.5±9.4 | 1.40 | 2.07 |

| Epilepsy (other IGE) | 11 | 19 | 34.8±13.2 | 17.4±13.9 | 1.53 | 1.83 |

All of the 89 epilepsy patients and 40 healthy control subjects participated in the study after providing informed consent for a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cincinnati. Each epilepsy patient underwent 1-3 consecutive 20-minute EEG/fMRI scans, and each healthy control subject underwent 1-2 consecutive scans. All patients and 20 control participants listened to self-selected music during scanning to increase comfort and compliance. The effect of music-listening on resting-state data is discussed elsewhere [Kay et al. 2012] and was included as a covariate in analysis. Eleven epilepsy patients did not complete the scanning procedure due to claustrophobia (n=3), metallic artifacts (n=1), or not wanting to continue the procedure (n=7). After excluding 25 low-quality scans (23 epilepsy, 2 control) and 37 epilepsy scans with abnormal EEG (i.e. GSWD), resting-state analysis was carried out on 189 scans from 60 idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) patients (122 scans) and 38 healthy controls (67 scans), see Table 1.

EEG Acquisition & Processing

Acquisition and processing of EEG data simultaneous with fMRI was carried out as previously described [Espay et al. 2008; Kay et al. 2012; Szaflarski et al. 2010b]. Briefly, subjects were fitted with an MRI-compatible EEG cap with electrodes arranged according to the international 10/20 system (Compumedics USA, Ltd., El Paso, TX). 64-channels of data, including an ECG channel, were recorded at 10 kHz concurrent with fMRI using an MRI compatible system. Time marks generated by the scanner at the onset of each volume acquisition were used to reduce gradient-related artifacts via an average artifact subtraction method [Allen et al. 2000]. Heartbeat timings generated from the ECG channel were used to reduce the ballistocardiographic artifact via a linear spatial filtering method [Lagerlund et al. 1997]. All EEG data were reviewed by a board certified epilepsy specialist (JPS). Based on this review, 37 scans containing GSWD from 25 patients (14 male, 11 female, age 29.1±12.0 years) were excluded from further analysis.

MRI Acquisition & Processing

Acquisition of MRI and fMRI data was carried out as previously described [DiFrancesco et al. 2008; Kay et al. 2012; Szaflarski et al. 2010b] on a 4 Tesla, 61.5 cm bore Varian Unity INOVA system (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a standard head coil. T1-weighted structural images were acquired for use as an anatomical reference. A modified driven equilibrium Fourier transform (MDEFT) method [Duewell et al. 1996; Uğurbil et al. 1993] was used with an 1100 millisecond inversion delay, 256 mm × 196 mm × 196 mm field of view, 256 × 196 × 196 voxel matrix, 22° flip angle, and TR/TE = 13.1/6.0 ms. T2*-weighted echo-planar functional images with blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast, were acquired with an 256 × 256 mm field of view, 64 × 64 voxel matrix, 90° flip angle, and 5 mm slice thickness in axial orientation without gap. 400 volumes consisting of 30 slices each and TR/TA = 3000/2000 ms were collected during each scan.

Data were reconstructed and corrected for geometric distortion and Nyquist ghosting with the aid of multi-echo reference scans (MERS) [Schmithorst et al. 2001]. Functional scans underwent slice timing correction, motion correction [Jenkinson et al. 2002], rigid-body registration to a high-resolution anatomical scan [Jenkinson & Smith, 2001], and non-linear registration [Andersson et al. 2007a; Andersson et al. 2007b] to an MNI152 standard using FSL [Smith et al. 2004]. Data were spatially blurred with a gaussian kernel of FWHM = 6 mm using AFNI [Cox 1996]. Since residual motion has been shown to have an artifactual effect on resting-state connectivity [Power et al. 2012; Van Dijk et al. 2012] data were lowpass filtered at 0.1 Hz [Cordes et al. 2001], and the six rigid-body motion parameters were regressed out of the data using AFNI in addition to the motion correction performed using FSL. Unfortunately, data on physiologic regressors such as pulse and breathing were unavailable.

The quality of functional to anatomical registration was measured using the mutual information cost function [Jenkinson & Smith, 2001]. 12 functional scans with an outlying cost indicating unsatisfactory registration were excluded from the study. The quality of motion correction was measured using the normalized correlation ratio cost function [Jenkinson & Smith, 2001] of each timepoint to the reference volume. 13 additional scans with outlying costs indicating excessive motion were excluded from the study.

Independent Component Analysis

Group ICA [Calhoun et al. 2001; Schmithorst & Holland, 2004] of all scans followed by dual regression [Filippini et al. 2009] was carried out using GIFT [Calhoun et al. 2009]. To make analysis of the large number of scans in the study computationally feasible, PCA reduction was applied in two steps. Each scan was reduced to 75 temporal components, the number suggested by the GIFT software, prior to temporal concatenation, and the concatenated result was reduced to 50 temporal components prior to ICA. The number of components used in the final reduction was chosen empirically [Schmithorst, 2005] because the number obtained using Bayesian information criterion (BIC) estimation [Calhoun et al. 2001] was very large. This process yielded 50 independent components.

Each independent component is thought to represent either a resting-state network, such as the DMN, or an artifact, such as head motion [Damoiseaux et al. 2006]. The most spatially comprehensive DMN component was identified visually and confirmed [Greicius et al. 2004] via DMN template distributed with GIFT. Component voxels with intensities greater than 99% of the robust range were used as an DMN region of interest (ROI), where the robust range was defined as the 2nd to 98th percentiles of voxel intensities. Voxels with a 50% or greater probability of being white matter, based on the JHU white matter atlas distributed with FSL, were excluded from the DMN ROI [Hua et al. 2008, Wakana et al. 2007].

Back-projection is the process by which a group component is translated onto a single scan. The back-projection of the group DMN component onto each scan was computed using dual regression [Filippini et al. 2009], a technique that normalizes component intensity across scans so as to allow for direct statistical comparisons between scans and between experimental groups. Back-projected component intensities of scans from the same subject were averaged voxelwise to obtain one map of DMN connectivity for each subject in the study. These per-subject connectivity maps were subsequently used in higher levels of analysis as described below.

Seed Based Voxel Correlation

Seed based voxel regression was done using AFNI’s 3dDeconvolve and 3dREMLfit tools [Cox, 1996]. A spherical seed region with a radius of 4 mm centered at MNI coordinates x = 2, y = −58, and z = 24, in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), was selected based on a previously reported seed region [McGill et al. 2012]. For each subject, the average fMRI time course within the seed region was used as the regressor of interest. Each subject’s fMRI time course was regressed voxelwise against the subject’s seed region time course. The t-values of the corresponding regression coefficients at each voxel were used as each subject’s connectivity map. 3dREMLfit was used to achieve prewhitening via an autoregressive (AR) model. No global signal regressor was used, as inclusion of a global signal regressor has been shown to introduce an unwanted bias [Weissenbacher et al. 2009].

The average of all subjects’ connectivity maps underwent a voxelwise one-sample t-test, and the resultant t-values were used as a group DMN connectivity map. Voxels in the group DMN connectivity map with intensities greater than 99% of the robust range were used as an DMN ROI, where the robust range was defined as the 2nd to 98th percentiles of voxel intensities. As above, voxels with a 50% or greater probability of being white matter, based on the JHU white matter atlas distributed with FSL, were excluded from the DMN ROI [Hua et al. 2008; Wakana et al. 2007].

Voxelwise Analysis

High-level analysis was performed using R [R Development Core Team, 2011; Whitcher et al. 2011]. Each analysis was repeated separately with data from ICA and dual regression and with data from seed-based voxel correlation. Voxelwise analysis using a two-sample t-test was carried out on subjects’ DMN connectivity maps to compare patients with uncontrolled seizures to healthy controls; age [Sambataro et al. 2010] and music-listening [Kay et al. 2012] were included as co-regressors. Voxelwise regression using a linear model with duration of epilepsy as the explanatory variable was carried out on DMN connectivity maps of patients with uncontrolled seizures. Resultant t-maps were masked with a dilated DMN ROI and corrected for multiple comparisons with cluster-based thresholding using AFNI.

Region of Interest Analysis

For ROI analysis, each subject’s DMN connectivity map was summarized by averaging voxels within the group DMN ROI. The resultant value was used as a measure of DMN connectivity for each subject. Linear models were used to assess the effect of epilepsy, duration of epilepsy, VPA-resistance, and uncontrolled seizures on connectivity.

Results

Voxelwise Analysis

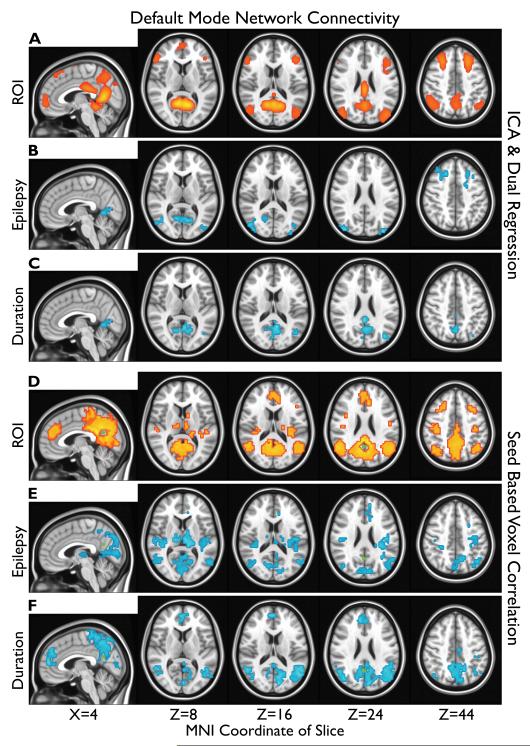

DMN ROIs are shown in Figure 1A, D. A significant (α=0.05) reduction in voxelwise DMN connectivity was observed in IGE patients with uncontrolled seizures compared to healthy controls (Figure 1B, E). No significant increases in DMN connectivity were observed within the DMN ROIs. Affected regions and Brodmann areas (BAs) included lingual gyrus/cuneus (BA 18, 19, 30, and 31), lateral occipital cortex (BA 19 and 39), and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, BA 6, 8, and 9) for analysis with ICA (Figure 1B). See Table S1 for a complete list of regions, BAs, and coordinates from Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Default mode network (DMN) regions of interest (ROIs) (A, D) and changes in connectivity related to epilepsy (B, C, E, F) are overlayed on the MNI152 standard brain in radiological orientation. Connectivity is shown in red, and reduced connectivity is shown in blue. MNI coordinates of slices are shown at bottom. Results from independent component analysis (ICA) are at top (A, B, C) and seed-based voxel correlations are at bottom (D, E, F). The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) seed region is shown in green (D, E, F). A, D: The top 1% of z-value in the group DMN independent component (z>0.84) or t-values in the group (n=98) PCC correlation map (t>15.18). B, E: Clusters (>36) of significantly (α=0.05, one-sided t<−1.68) reduced connectivity in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy (n=16) v.s. healthy controls (n=38). C, F: Clusters (>36) of significantly (α=0.05, one-sided t<−1.77) reduced connectivity correlated with duration of epilepsy in patients with uncontrolled seizures (n=16).

Voxelwise DMN connectivity exhibited a significant (α=0.05) negative correlation with duration of disease in epilepsy patients with uncontrolled seizures (Figure 1C, F). No significant positive correlations between DMN connectivity and duration were observed within the DMN ROIs. Affected regions and BAs included hippocampus (not shown, BA 36 and 37), lingual gyrus/cuneus/posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and lateral occipital cortex for analysis with ICA (Figure 1C). See Table S1. No significant voxelwise negative correlation between DMN connectivity and duration of disease was observed in epilepsy patients whose seizures were controlled (data not shown).

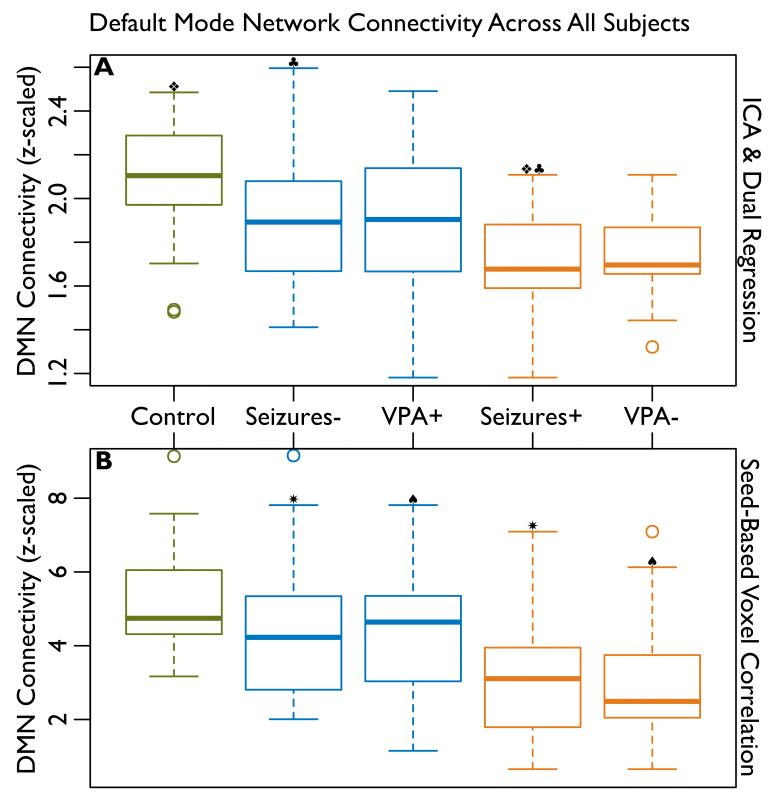

Region of Interest Analysis

The differences in DMN connectivity among IGE patients and between patients and healthy controls are summarized in Figure 2 and the differences between epilepsy patients and healthy controls, while controlling for age and music-listening, in Table 2. The difference in connectivity between healthy control subjects and all epilepsy patients was not statistically significant (α=0.05, p=0.64). However when epilepsy patients with uncontrolled seizures were considered separately, their connectivity was observed to be significantly reduced when compared to healthy controls using ICA (p=0.019). VPA-resistant patients also trended toward reduced connectivity (p=0.094).

Figure 2.

Average connectivity within default mode network (DMN) regions of interest (ROIs, see Figure 1) for healthy control subjects (Control, n=38), epilepsy patients whose seizures are controlled (Seizures−, n=44), patients who respond to the drug valproate (VPA+, n=28), patients with uncontrolled seizures (Seizures+, n=16), and patients resistant to valproate (VPA−, n=13). The effects of age and music listening have been regressed out of connectivity in healthy controls. The effect of duration has been regressed out of connectivity in epilepsy patients. The symbols, ❖, ♣, ✷, and ♠ indicate significant (α=0.05) differences, see Tables 2 and 4. A: DMN connectivity measured using independent component analysis (ICA). B: DMN connectivity measured using seed-based voxel correlation.

Table 2. The Effect of Epilepsy v.s. Healthy Controls.

Region of interest (ROI) analysis of default mode network (DMN) connectivity in epilepsy patients compared to healthy control subjects, with age and music-listening as covariates. Sample size (n), effect size, standard error (SE), degrees of freedom (DF), and two-sided p-values are shown.

| Healthy Control Subjects (n=38) v.s. | Effect Size | SE | DF | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA & Dual Regression |

All Epilepsy (n=60) | −0.035 | 0.075 | 94 | 0.642 |

| Seizures− (n=44) | 0.031 | 0.074 | 78 | 0.674 | |

| Seizures+ (n=16) | −0.220 | 0.091 | 50 | 0.019 | |

| VPA+ (n=28) | 0.013 | 0.087 | 62 | 0.880 | |

| VPA− (n=13) | −0.163 | 0.094 | 47 | 0.094 | |

| Seed-Based Voxel Correlation |

All Epilepsy (n=60) | −0.011 | 0.443 | 94 | 0.981 |

| Seizures− (n=44) | 0.306 | 0.437 | 78 | 0.486 | |

| Seizures+ (n=16) | −0.966 | 0.517 | 50 | 0.068 | |

| VPA+ (n=28) | 0.412 | 0.473 | 62 | 0.387 | |

The effects of VPA-resistance (v.s. responsiveness) and uncontrolled seizures (v.s. controlled seizures) on DMN connectivity in IGE patients without controlling for duration of disease are shown in Table 3 and when controlling for duration of disease in Table 4. A significant (p=0.024) reduction in connectivity was observed for patients with uncontrolled seizures. VPA-resistance also trended toward reduced connectivity, but this trend was diminished (p=0.19) when the effect of duration was taken into account.

Table 3. The Effect of Treatment-Resistance (v.s. Response).

Region of interest (ROI) analysis of default mode network (DMN) connectivity for VPA-resistance (VPA−) compared to response (VPA+) and for uncontrolled seizures (Seizures+) compared to controlled (Seizures−) in epilepsy patients. Sample size (n), effect size, standard error (SE), degrees of freedom (DF), and two-sided p-values are shown.

| DMN in Epilepsy Patients | Effect Size | SE | DF | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA & Dual Regression |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −0.215 | 0.093 | 58 | 0.024 |

| VPA− (n=13) v.s. VPA+ (n=28) | −0.281 | 0.114 | 39 | 0.018 | |

| Seed-Based Voxel Correlation |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −1.211 | 0.507 | 58 | 0.020 |

| VPA− (n=13) v.s. VPA+ (n=28) | −1.479 | 0.590 | 39 | 0.017 | |

Table 4. The Effect of Treatment Resistance (v.s. Response), Adjusted for Duration.

Region of interest (ROI) analysis of default mode network (DMN) connectivity for VPA-resistance (VPA−) compared to response (VPA+) and for uncontrolled seizures (Seizures+) compared to controlled (Seizures−) in epilepsy patients, with duration of disease as a covariate. Sample size (n), effect size, standard error (SE), degrees of freedom (DF), and two-sided p-values are shown.

| DMN in Epilepsy Patients | Effect Size | SE | DF | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA & Dual Regression |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −0.200 | 0.086 | 57 | 0.024 |

| VPA− (n=13) v.s. VPA+ (n=28) | −0.152 | 0.114 | 38 | 0.189 | |

| Seed-Based Voxel Correlation |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −1.212 | 0.513 | 57 | 0.021 |

| VPA− (n=13) v.s. VPA+ (n=28) | −1.451 | 0.652 | 38 | 0.032 | |

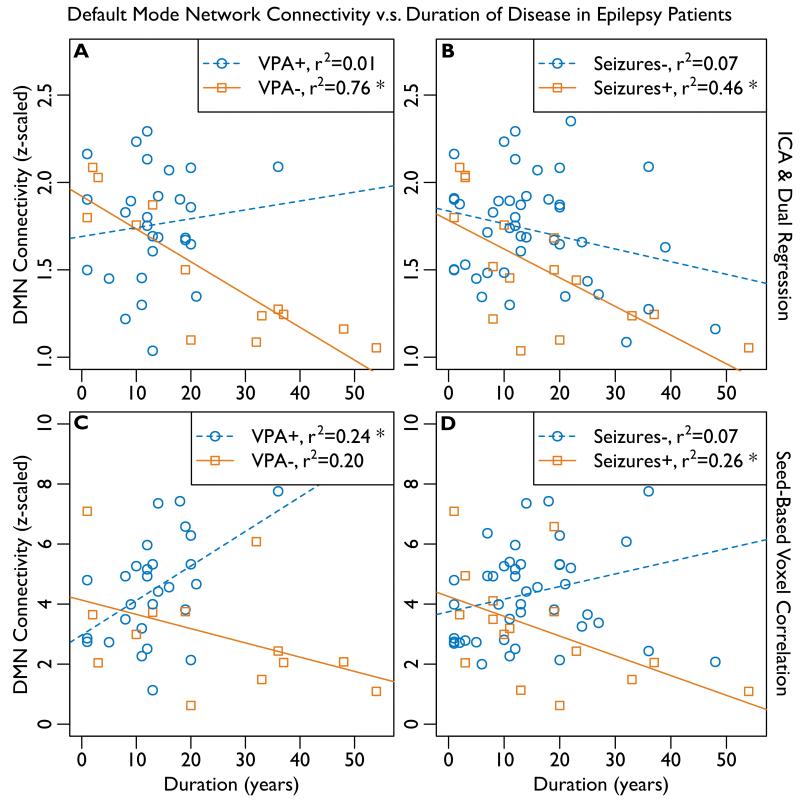

The correlation between DMN connectivity and duration of disease in IGE patients is summarized in Figure 3 and shown in Table 5. The difference in the correlation between DMN connectivity and duration of disease among IGE patients is shown in Table 6. The correlation between connectivity and duration was observed to be significantly negative in patients with VPA-resistance (p<0.001) and uncontrolled seizures (p=0.004) using ICA whereas this correlation was either not significant or, paradoxically, positive in VPA-responders (p=0.56) and patients whose seizures were controlled (p=0.086). Using ICA, the difference in the magnitude of correlation (i.e. difference in slopes of the best fit lines) was significant (p=0.013) for VPA-resistant v.s. VPA-responsive patients, and it trended toward significance (p=0.15) for patients with uncontrolled v.s. controlled seizures.

Figure 3.

Average connectivity within default mode network (DMN) regions of interest (ROIs, see Figure 1) is correlated with duration of epilepsy. The coefficient of determination, r2, is given; significant (α=0.05) correlations are indicated with “*”, see Tables 5 and 6. The results of independent component analysis (ICA) are shown at top (A, B). The results of seed-based voxel correlation are shown at bottom (C, D). A, C: Patients who responded to the drug valproate (VPA+, n=28) are compared to patients resistant to valproate (VPA−, n=13) at left. B, D: Patients whose seizures are controlled (Seizures−, n=44) are compared to patients with uncontrolled seizures (Seizures+, n=16) at right.

Table 5. The Relationship Between Connectivity & Duration.

Region of interest (ROI) analysis of default mode network (DMN) connectivity v.s. duration of disease in epilepsy patients. VPA− = valproate non-responders, Seizures+ = uncontrolled seizures. Sample size (n), effect size, standard error (SE), degrees of freedom (DF), and two-sided p-values are shown.

| DMN v.s. Duration of Epilepsy | Effect Size | SE | DF | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA & Dual Regression |

All Epilepsy (n=60) | −0.011 | 0.003 | 58 | 0.001 |

| Seizures− (n=44) | −0.007 | 0.004 | 42 | 0.086 | |

| Seizures+ (n=16) | −0.016 | 0.005 | 14 | 0.004 | |

| VPA+ (n=28) | 0.005 | 0.009 | 26 | 0.556 | |

| VPA− (n=13) | −0.019 | 0.003 | 11 | <0.001 | |

| Seed-Based Voxel Correlation |

All Epilepsy (n=60) | −0.002 | 0.020 | 58 | 0.939 |

| Seizures− (n=44) | 0.042 | 0.023 | 42 | 0.072 | |

| Seizures+ (n=16) | −0.066 | 0.030 | 14 | 0.042 | |

| VPA+ (n=28) | 0.115 | 0.040 | 26 | 0.008 | |

| VPA− (n=13) | −0.047 | 0.029 | 11 | 0.126 | |

Table 6. Differences in the Relationship Between Connectivity & Duration.

Region of interest (ROI) analysis comparing the difference in the slope (effect size from Table 5) of the linear relationship between default mode network (DMN) connectivity and duration of epilepsy. The slope is compared between VPA-resistant (VPA−) v.s. VPA-responsive (VPA+) patients and between patients with uncontrolled seizures (Seizures+) v.s. controlled seizures (Seizures−). Sample size (n), effect size, standard error (SE), degrees of freedom (DF), and two-sided p-values are shown.

| Differences in DMN v.s. Duration of Epilepsy | Effect Size | SE | DF | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA & Dual Regression |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −0.009 | 0.006 | 56 | 0.151 |

| VPA− (n=13) v.s. VPA+ (n=28) | −0.024 | 0.009 | 37 | 0.013 | |

| Seed-Based Voxel Correlation |

Seizures+ (n=16) v.s. Seizures− (n=44) | −0.108 | 0.037 | 56 | 0.005 |

Discussion

In this study we examined the effect of resistance to VPA and the effect of uncontrolled seizures on resting-state DMN functional connectivity. We found that VPA-resistance and uncontrolled seizures are associated with a greater reduction in DMN connectivity than epilepsy alone. These findings confirm that the DMN [Luo et al. 2011; McGill et al. 2012] is among the resting-state features [Bai et al. 2011, Killory et al. 2011] that differ between IGE patients and healthy controls.

Previous resting-state fMRI studies have found that DMN connectivity is reduced in IGE patients v.s. healthy control subjects, and that this reduction is correlated with duration of disease [Luo et al. 2011; McGill et al. 2012]. However, we are not aware of any previous studies that specifically investigated the effect of treatment-resistance on connectivity in IGE. Our results suggest that reduced DMN connectivity in patients with IGE as a whole is due predominantly to the presence of treatment-resistant patients within the study population. When treatment-resistant and treatment-responsive patients are considered separately, treatment-resistance is associated with significantly lower connectivity whereas, depending on the technique used, it may not be possible to distinguish between treatment-responsive patients and healthy controls; see Figure 2 and Tables 2-4. These findings are consistent with a neurological contribution to the etiology of treatment-resistance and suggest that reduced DMN connectivity may be useful as a biomarker for treatment-resistance.

It is notable that DMN connectivity declines with duration of epilepsy [Luo et al. 2011; McGill et al. 2012], and that this diminishing effect is significantly more pronounced in treatment-resistant patients (Figure 3 and Tables 5-6). This finding suggests a cumulative effect of epilepsy on the brain and, if replicated, might weigh in favor of a clinical decision to treat aggressively. It would be interesting to learn if uncontrolled seizures have a uniform effect on connectivity or if seizure or GSWD frequency is negatively correlated with DMN connectivity. Lack of detailed information on seizure load (number of seizures per unit of time) or GSWD frequency during 24 hour monitoring did not allow for these analyses in this study.

This study investigated a cross-section of IGE that included newly diagnosed patients as well as patients who had lived with epilepsy for more than 50 years. As such, it was not possible to directly examine whether reduced DMN connectivity is an outcome of treatment-resistance or a predictor of it. We came close to this question by including treatment-resistance and duration of disease in the same model (Tables 3 and 4). Using ICA, we found that the effect of uncontrolled seizures on connectivity remains significant even after controlling for the effect of duration. Although the effect of VPA-resistance was significant on its own, it did not reach our threshold for significance (α=0.05) after controlling for duration. This could have been due to the small number of VPA-resistant patients in the study (n=13) or to a confounding correlation between VPA-resistance and duration. VPA-resistant patients were observed to be older (by 8.1±3.5 years, p<0.05) and to have had epilepsy for a longer period of time (by 10.5±3.9 years, p<0.01) than VPA-responders. Although including duration in the model of connectivity v.s. VPA response was appropriate (F=7.85, p=0.008), its collinearity with VPA-resistance precipitated a drop in statistical power from 0.96 to an unsatisfactory level of 0.60. A prospective study of newly-diagnosed drug-naïve IGE patients would help resolve this confound and establish whether DMN connectivity can predict treatment-resistance. At least one such study [Moeller et al. 2008b] has demonstrated deactivation of DMN regions during GSWD in a drug-naïve population.

We had not expected to observe a correlation between VPA status and age or duration, and no such correlation was observed for uncontrolled v.s. controlled seizures (p>0.4). We postulate that, due to the less favorable adverse effects profile of VPA compared to newer drugs, nowadays clinicians are postponing treatment with VPA until other treatment options have been exhausted. This bias was especially evident in women of childbearing age (χ2=4.86, p=0.053); fortunately, we were able to recruit a similar number of men (n=21) and women (n=20) who had tried VPA. Response to VPA among those who had tried it was also similar between men (14/21) and women (14/20; Table 1).

Drugs represent another possible confound in our study, as these neuromodulatory agents could plausibly modulate the DMN independently from their effects on epilepsy [e.g., Szaflarski & Allendorfer, 2012]. Unfortunately, the large number of different anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) combined with the high proportion of patients on AED polytherapy preclude modeling every AED’s effect separately. We instead considered the number of current drugs (taken at the time of scanning) and the number of previously failed drugs (Table 1). As expected, patients who were taking more (p=0.023) or had failed more (p<0.001) medications were more likely to have uncontrolled seizures. On the other hand, number of current drugs was a poor predictor in the model of connectivity vs. uncontrolled seizures and duration (F=1.51, p=0.224). This lack of correlation is unsurprising because there is no reason to expect that all drugs would have the same effect (i.e. increasing or decreasing) on connectivity. We estimate that an additional 54 epilepsy patients would be needed to retain the statistical power of the original model and conclusively refute the possibility that observed differences in DMN connectivity were due to drug effects rather than treatment-resistance. Again, a prospective study would help to resolve these confounds.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of DMN connectivity in IGE to use independent component analysis (ICA) and dual regression. We performed confirmatory analysis using the more common technique of seed-based voxel correlation. These two techniques yielded similar findings. Both showed greater changes in posterior than anterior regions. The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) is considered the “hub” of the DMN [Greicius et al. 2003], and so may have been more severely affected by IGE. Also, posterior DMN regions are larger than anterior ones and thus may have been favored by cluster-based thresholding; ancillary ROI analysis was not affected by this factor. Seed-based voxel correlation showed decreased connectivity in the thalamus associated with uncontrolled IGE whereas ICA did not show thalamus to be part of the DMN. The interpretation of this discrepancy is unclear because thalamus is not classically considered part of the DMN [Raichle et al. 2001]. Nevertheless, thalamus is functionally and structurally connected to DMN regions in cortex [Greicius et al. 2003; Greicius et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2008] and has been observed to modulate DMN connectivity [Jones et al. 2011]. Reduced DMN connectivity in thalamus could arise due to generalized spike and wave discharges (GSWD) produced by cortico-thalamic circuits [Contreras et al. 1996; Moeller et al. 2008a].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23 NS052468) and in part by funds from the Department of Neurology at the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA. The first author received support from the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) at the University of Cincinnati (T32 GM063483). The authors wish to thank Mekibib Altaye, Ph.D. at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center for his assistance in validating our statistical methods.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- Allen PJ, Josephs O, Turner R. A method for removing imaging artifact from continuous EEG recorded during functional MRI. Neuroimage. 2000;12:230–9. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith S. Non-linear optimisation. FMRIB technical report TR07JA1. 2007a www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep.

- Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith S. Non-linear registration, aka Spatial normalisation FMRIB technical report TR07JA2. 2007b www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep.

- Aghakhani Y, Bagshaw AP, Bénar CG, Hawco C, Andermann F, Dubeau F, Gotman J. fMRI activation during spike and wave discharges in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Brain. 2004;127:1127–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Guo J, Killory B, Vestal M, Berman R, Negishi M, Danielson N, Novotny EJ, Constable RT, Blumenfeld H. Resting functional connectivity between the hemispheres in childhood absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2011;76:1960–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e54de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:140–51. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Liu J, Adali T. A review of group ICA for fMRI data and ICA for joint inference of imaging, genetic, and ERP data. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy Proposal for Revised Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;1989(30):389–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ, Steriade M. Control of spatiotemporal coherence of a thalamic oscillation by corticothalamic feedback. Science. 1996;274:771–4. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes D, Haughton VM, Arfanakis K, Carew JD, Turski PA, Moritz CH, Quigley MA, Meyerand ME. Frequencies contributing to functional connectivity in the cerebral cortex in “resting-state” data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1326–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13848–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601417103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson NB, Guo JN, Blumenfeld H. The default mode network and altered consciousness in epilepsy. Behav Neurol. 2011;24:55–65. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2011-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco MW, Holland SK, Szaflarski JP. Simultaneous EEG/functional magnetic resonance imaging at 4 Tesla: correlates of brain activity to spontaneous alpha rhythm during relaxation. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;25:255–64. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e3181879d56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duewell S, Wolff SD, Wen H, Balaban RS, Jezzard P. MR imaging contrast in human brain tissue: assessment and optimization at 4 T. Radiology. 1996;199:780–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.3.8638005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr. Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. 2nd Edition. Raven Press; New York: 1993. Chapters 9-10. [Google Scholar]

- Espay AJ, Schmithorst VJ, Szaflarski JP. Chronic isolated hemifacial spasm as a manifestation of epilepsia partialis continua. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:332–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faught E. Treatment of refractory primary generalized epilepsy. Rev Neurol Dis. 2004;1:S34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF, Mackay CE. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7209–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, Abou-Khalil B, Browne T, Harden CL, Theodore WH, Bazil C, Stern J, Schachter SC, Bergen D, Hirtz D, Montouris GD, Nespeca M, Gidal B, Marks WJ, Jr, Turk WR, Fischer JH, Bourgeois B, Wilner A, Faught RE, Jr, Sachdeo RC, Beydoun A, Glauser TA. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs II: treatment of refractory epilepsy: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2004;62:1261–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123695.22623.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotman J, Grova C, Bagshaw A, Kobayashi E, Aghakhani Y, Dubeau F. Generalized epileptic discharges show thalamocortical activation and suspension of the default state of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15236–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504935102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotman J, Kobayashi E, Bagshaw AP, Bénar CG, Dubeau F. Combining EEG and fMRI: a multimodal tool for epilepsy research. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;23:906–20. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4637–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:72–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groomes LB, Pyzik PL, Turner Z, Dorward JL, Goode VH, Kossoff EH. Do patients with absence epilepsy respond to ketogenic diets? J Child Neurol. 2011;26:160–5. doi: 10.1177/0883073810376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland KD, Monahan S, Morita D, Vartzelis G, Glauser TA. Valproate in children with newly diagnosed idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:149–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua K, Zhang J, Wakana S, Jiang H, Li X, Reich DS, Calabresi PA, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC, Mori S. Tract probability maps in stereotaxic spaces: analyses of white matter anatomy and tract-specific quantification. Neuroimage. 2008;39:336–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallon P, Latour P. Epidemiology of idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2005;46:10–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–56. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):825–41. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Mateen FJ, Lucchinetti CF, Jack CR, Jr, Welker KM. Default mode network disruption secondary to a lesion in the anterior thalamus. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:242–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay BP, Meng X, DiFrancesco MW, Holland SK, Szaflarski JP. Moderating effects of music on resting state networks. Brain Res. 2012;1447:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killory BD, Bai X, Negishi M, Vega C, Spann MN, Vestal M, Guo J, Berman R, Danielson N, Trejo J, Shisler D, Novotny EJ, Jr, Constable RT, Blumenfeld H. Impaired attention and network connectivity in childhood absence epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2011;56:2209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostov H, Larsson PG, Røste GK. Is vagus nerve stimulation a treatment option for patients with drug-resistant idiopathic generalized epilepsy? Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2007;187:55–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labar D, Murphy J, Tecoma E. Vagus nerve stimulation for medication-resistant generalized epilepsy. Neurology. 1999;52:1510–2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerlund TD, Sharbrough FW, Busacker NE. Spatial filtering of multichannel electroencephalographic recordings through principal component analysis by singular value decomposition. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;14:73–82. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs H, Lengler U, Hamandi K, Kleinschmidt A, Krakow K. Linking generalized spike-and-wave discharges and resting state brain activity by using EEG/fMRI in a patient with absence seizures. Epilepsia. 2006;47:444–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C, Li Q, Lai Y, Xia Y, Qin Y, Liao W, Li S, Zhou D, Yao D, Gong Q. Altered functional connectivity in default mode network in absence epilepsy: a resting-state fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:438–49. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Wang B, Chen X, Xiong J. Detecting functional connectivity in the resting brain: a comparison between ICA and CCA. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill ML, Devinsky O, Kelly C, Milham M, Castellanos FX, Quinn BT, DuBois J, Young JR, Carlson C, French J, Kuzniecky R, Halgren E, Thesen T. Default mode network abnormalities in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F, Siebner HR, Wolff S, Muhle H, Boor R, Granert O, Jansen O, Stephani U, Siniatchkin M. Changes in activity of striato-thalamo-cortical network precede generalized spike wave discharges. Neuroimage. 2008a;39:1839–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F, Siebner HR, Wolff S, Muhle H, Granert O, Jansen O, Stephani U, Siniatchkin M. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI in drug-naive children with newly diagnosed absence epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008b;49:1510–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Devinsky O. Vagus nerve stimulation for refractory idiopathic generalised epilepsy. Seizure. 2004;13:176–8. doi: 10.1016/S1059-1311(03)00147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opeskin K, Kalnins RM, Halliday G, Cartwright H, Berkovic SF. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy: lack of significant microdysgenesis. Neurology. 2000;55:1101–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2011 http://www.R-project.org.

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambataro F, Murty VP, Callicott JH, Tan HY, Das S, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS. Age-related alterations in default mode network: impact on working memory performance. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:839–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ, Dardzinski BJ, Holland SK. Simultaneous correction of ghost and geometric distortion artifacts in EPI using a multiecho reference scan. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:535–9. doi: 10.1109/42.929619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ, Holland SK. Comparison of three methods for generating group statistical inferences from independent component analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging data. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:365–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ. Separate cortical networks involved in music perception: preliminary functional MRI evidence for modularity of music processing. Neuroimage. 2005;25:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Allendorfer JB. Topiramate and its effect on fMRI of language in patients with right or left temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Rackley AY, Lindsell CJ, Szaflarski M, Yates SL. Seizure control in patients with epilepsy: the physician vs. medication factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:264. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Lindsell CJ, Zakaria T, Banks C, Privitera MD. Seizure control in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsies: EEG determinants of medication response. Epilepsy Behav. 2010a;17:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, DiFrancesco MW, Hirschauer T, Banks C, Privitera MD, Gotman J, Holland SK. Cortical and subcortical contributions to absence seizure onset examined with EEG/fMRI. Epilepsy Behav. 2010b;18:404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyvaert L, Chassagnon S, Sadikot A, LeVan P, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Thalamic nuclei activity in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: an EEG-fMRI study. Neurology. 2009;73:2018–22. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c55d02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uğurbil K, Garwood M, Ellermann J, Hendrich K, Hinke R, Hu X, Kim SG, Menon R, Merkle H, Ogawa S, et al. Imaging at high magnetic fields: initial experiences at 4 T. Magn Reson Q. 1993;9:259–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch K, Stern JM. Epilepsy surgery in adults. 2006 http://www.medmerits.com/index.php/article/epilepsy_surgery_in_adults.

- Van Dijk KR, Sabuncu MR, Buckner RL. The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;59:431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakana S, Caprihan A, Panzenboeck MM, Fallon JH, Perry M, Gollub RL, Hua K, Zhang J, Jiang H, Dubey P, Blitz A, van Zijl P, Mori S. Reproducibility of quantitative tractography methods applied to cerebral white matter. Neuroimage. 2007;36:630–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenbacher A, Kasess C, Gerstl F, Lanzenberger R, Moser E, Windischberger C. Correlations and anticorrelations in resting-state functional connectivity MRI: a quantitative comparison of preprocessing strategies. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1408–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcher B, Schmid VJ, Thornton A. Working with the DICOM and NIfTI Data Standards in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;44:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yenjun S, Harvey AS, Marini C, Newton MR, King MA, Berkovic SF. EEG in adult-onset idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:242–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.26402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Snyder AZ, Fox MD, Sansbury MW, Shimony JS, Raichle ME. Intrinsic functional relations between human cerebral cortex and thalamus. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1740–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.90463.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Liao W, Chen H, Mantini D, Ding JR, Xu Q, Wang Z, Yuan C, Chen G, Jiao Q, Lu G. Altered functional-structural coupling of large-scale brain networks in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Brain. 2011;134:2912–28. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.