Abstract

Mouse serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is frequently measured and interpreted in mammalian bone research, however; little is known about the circulating ALPs in mice and their relation to human ALP isozymes and isoforms. Mouse ALP was extracted from liver, kidney, intestine, and bone from vertebra, femur and calvaria tissues. Serum from mixed strains of wild-type (WT) mice and from individual ALP knockout strains were investigated, i.e., Alpl−/− (a.k.a. Akp2 encoding tissue-nonspecific ALP or TNALP), Akp3−/− (encoding duodenum-specific intestinal ALP or dIALP), and Alpi−/− (a.k.a. Akp6 encoding global intestinal ALP or gIALP). The ALP isozymes and isoforms were identified by various techniques and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography. Results from the WT and knockout mouse models revealed identical bone-specific ALP isoforms (B/I, B1, and B2) as found in human serum, but in addition mouse serum contains the B1x isoform only detected earlier in patients with chronic kidney disease and in human bone tissue. The two murine intestinal isozymes, dIALP and gIALP, were also identified in mouse serum. All four bone-specific ALP isoforms (B/I, B1x, B1, and B2) were identified in bone tissues from mice, in good correspondence with those found in human bones. All mouse tissues, except liver and colon, contained significant ALP activities. This is a notable difference as human liver contains vast amounts of ALP. Histochemical staining, Northern and Western blot analysis confirmed undetectable ALP expression in liver tissue. ALP activity staining showed some positive staining in the bile canaliculi for BALB/c and FVB/N WT mice, but not in C57Bl/6 and ICR mice. Taken together, while the main source of ALP in human serum originates from bone and liver, and a small fraction from intestine (<5%), mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP, including all four isoforms, B/I, B1x, B1, and B2, and two intestinal ALP isozymes dIALP and gIALP. We suggest that the genetic nomenclature for the Alpl gene in mice (i.e., ALP liver) should be reconsidered since murine liver has undetectable amounts of ALP activity. These findings should pave the way for the development of user-friendly assays measuring circulating bone-specific ALP in mice models used in bone and mineral research.

Keywords: alkaline phosphatase, bone, glycosylation, hypophosphatasia, knockout mice, mineralization

Introduction

Alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1, ALP) is a family of enzymes that is present in most species from bacteria to man [1]. ALP catalyses the hydrolysis of a wide range of phosphomonoesters, in vitro at an alkaline pH, and is present in practically all tissues in the human body, anchored to the cell membrane lipid bilayer via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) moiety [2].

Mice are often used as animal models to study genetic and molecular control of bone and mineral metabolism, gastrointestinal physiology and other cellular and hormonal mechanisms in order to elucidate biological functions. Less attention has been given to markers of bone remodeling (turnover) suitable for skeletal research on rodents. Some assays have, however, been developed for determination of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRACP5b) [3], carboxy-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) [4–5], amino-terminal procollagen type I propeptide (PINP) [6], and osteocalcin [7] in mouse and rat serum. However, no commercial assay has been successfully developed for determination of mouse serum bone ALP [8], and most “in-house” methods assume that mice have approximately the same constitution of ALP isozymes and isoforms as humans [9].

In humans, there are four gene loci encoding ALP isozymes, i.e., intestinal ALP (IALP) encoded by the ALPI gene, placental ALP (PALP) encoded by the ALPP gene, germ cell ALP (GCALP) encoded by the ALPP2 gene, and tissue-nonspecific ALP (TNALP) encoded by the ALPL gene (Table 1). The tissue-specific ALPs (i.e., IALP, PALP, and GCALP) are clustered on chromosome 2, bands q34.2 – q37, and are 87 – 98% homologous to each other, but only about 50% identical to TNALP, which is located on chromosome 1, bands p36.1 – p34 q37 [10–12]. The highest levels of human TNALP is expressed in bone and liver, and account for about 95% of the total ALP activity in serum, with a ratio of approximately 1:1 in healthy adults [13]. While the TNALP gene is not highly polymorphic, the TNALP isozyme exists as numerous isoforms in biological fluids differing primarily in the extent and type of glycosylation [14–16]. At least six different TNALP isoforms can be separated and quantified by weak anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), in serum from healthy individuals: one bone/intestinal (B/I), two bone (B1 and B2), and three liver ALP isoforms (L1, L2, and L3). A fourth bone-specific ALP isoform, identified as B1x, has also been demonstrated in serum from patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) [17–18], and in extracts of human bone tissue [19].

Table 1.

Nomenclature and accession numbers of the human and mouse ALP isozymes and genes.

| Gene | Protein name (abbreviation) | Tissue distribution | Function | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human genes: | ||||

| ALPL | Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase; “liver-bone-kidney type” ALP (TNALP) | Developing nervous system, skeletal tissue, liver and kidney | Skeletal mineralization | NM_000478 |

| ALPP | Placental alkaline phosphatase (PALP) | Syncytiotrophoblast, a variety of tumors | Unknown | NM_001632 |

| ALPP2 | Germ cell alkaline phosphatase (GCALP) | Testis, malignant trophoblasts, testicular cancer | Unknown | NM_031313 |

| ALPI | Intestinal alkaline phosphatase (IALP) | Gut, influenced by feeding and ABO blood group status | Fat absorption Detoxyfication of lipopolysaccharide | NM_001631 |

| Mouse genes: | ||||

| Alpl (Akp2) | Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase; “liver-bone-kidney type” ALP (TNALP) | Developing nervous system, skeletal tissues and kidney | Skeletal mineralization | NM_007431 |

| Akp3 | Duodenum-specific intestinal alkaline phosphatase (dIALP) | Gut | Fat absorption Detoxyfication of lipopolysaccharide | NM_007432 |

| Alppl2 (Akp5) | Embryonic alkaline phosphatase (EALP) | Preimplantation embryo, testis, gut | Early embryogenesis | NM_007433 |

| Akp-ps1 | ALP pseudogene, pseudoALP | Not transcribed | NG 001340 | |

| Alpi (Akp6) | Global intestinal alkaline phosphatase (gIALP) | Gut | Under investigation | AK008000 |

LPS = Lipopolysaccharide

Fifty-two amino acids, out of 524 amino acids for the entire protein, are different between mouse and human TNALP on the protein level, and they contain the same putative N-linked residues. The mouse ALP genome is very similar to the human in organization, but there are some differences in the expression of the genes (Table 1). Five ALP loci have been described in the mouse genome: TNALP (Alpl, a.k.a Akp2), embryonic ALP (EALP, Alppl2, a.k.a. Akp5), two different IALP, i.e., the duodenum-specific IALP (dIALP) (Akp3 gene) and a global IALP (gIALP) (Alpi, a.k.a. Akp6 gene), and a putative pseudo-ALP. In humans, the TNALP isozyme is mostly expressed in liver, kidney and bone, but TNALP is also expressed in the placenta during the first trimester of pregnancy and in the neural tube during development [20–21]. In mice, the TNALP gene Alpl is also expressed in the placenta and primordial germ cells [22–23]. IALPs are encoded by the mouse Akp3 and Alpi genes and the Alppl2 gene encodes for EALP, all three located on chromosome 1 [24]. EALP appears to be related to the human PALP and GCALP isozymes and is expressed under the early embryonic period, but is not detectable after embryonic day seven. IALPs expression is restricted to the intestine, but can also be expressed in thymus and embryonic stem cells. The ALP pseudogene (Akp-ps1) has high homology to EALP and IALP, but the gene is not transcribed [23–25].

This study was primarily designed to characterize the circulating and tissue-derived mouse ALP isozymes and isoforms. Here we report that no ALP activity is detectable in mouse liver, and nor did we detect any liver ALP in the circulation. Furthermore, mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP (including all four bone isoforms B/I, B1x, B1, and B2) and both IALP isozymes, i.e., dIALP (Akp3) and gIALP (Alpi). We used tissues and serum from wild-type (WT) mice and ALP knockout mice models to investigate the localization and properties of the murine isozymes in relation to the known composition of circulating human ALP isozymes and isoforms.

Materials and Methods

Tissue sources and serum from WT and ALP knockout mice

Liver, kidney, intestine, and bone from vertebra, femur and calvaria were obtained from 20 BALB/c WT female mice, 7 to 9 weeks old. The different organs/tissues were divided into four groups (one group contained the same organ from five mice). A separate group of mouse intestines, isolated in 7 segments in a total from 8 WT mice, were also collected and ingesta/feces washed out with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Additional mouse tissues and serum were also collected from four different WT mice strains, 8-week-old males (5 in each group): C57Bl/6J and BALB/c male mice (Jackson laboratory, Sacramento, CA, USA) and FVB/N and ICR male mice (Taconic Farm Inc., Oxnard, CA, USA). The ApoE-TNALP transgenic (Tg) (+) mouse line (used as positive control for Western blot analysis and ALP histochemical staining) was reported previously [26]. Sera from ALP knockout mouse strains (corresponding protein name) were also assessed: i.e., Alpl+/+, Alpl+/− and Alpl−/− (TNALP); Akp3+/+ and Akp3−/− (dIALP); and Alpi+/+ and Alpi−/− (gIALP). The genetic background of the Alpl knockout line is hybrids of C57Bl/6 and 129/Sv+/+, and both the Akp3 knockout and Alpi knockout lines have C57Bl/6 backgrounds. Mouse blood was collected by cardiac acupuncture from mice anesthetized with Avertin (0.017 mL/g body weight), and the serum samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. Commercially available preparations, pooled from mixed strains of WT mice (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), were also assessed.

Separation and quantitation by HPLC

Serum and extracts from the different tissue samples were determined by a previously described HPLC for separation and quantitation of ALP isozymes and isoforms [27–28]. In brief, the ALP samples were separated using a gradient of 0.6 M sodium acetate on a weak anion-exchange column, SynChropak AX300 (250×4.6 mm I.D.) (Eprogen, Inc., Downers Grove, IL, USA). The effluent was mixed on-line with the substrate solution [1.8 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) in a 0.25 M diethanolamine (DEA) buffer at pH 10.1] and the ensuing reaction took place in a packed-bed post-column reactor at 37°C. The formed product (p-nitrophenol) was then directed on-line through the detector set at 405 nm. The areas under each peak were integrated and the total ALP activity used to calculate the relative activity of each of the detected ALP isoforms.

Measurements of ALP activity and protein concentration

Total ALP was measured by a kinetic assay in a 96-well microtitre plate format. In brief, a total volume of 300 μL solution was added per well, containing 1.0 M DEA buffer (pH 9.8), 1.0 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM pNPP. The time-dependent increase in absorbance at 405 nm (reflecting p-nitrophenol production) was determined on a Multiscan Spectrum microplate reader (Thermo Electron Corp., Vantaa, Finland). The relation between the enzymatic activity units kat and U is 1.0 μkat/L corresponds to 60 U/L. Total protein concentrations were measured by the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) [29].

ALP histochemical staining, Northern and Western blot analysis

ALP histochemical staining was processed as previously described [21], and pictures were taken by a Nikon TE300 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). Total RNA for Northern blot analysis was extracted from WT mouse liver and kidney tissues and subjected to Northern blot hybridization as previously described [30]. To detect mouse TNALP mRNA, 1.1 kb cDNA fragment from 3′ region of mouse TNALP cDNA (NM_007431) was used as a probe, while a probe of mouse L32 ribosomal protein was used as standard. Protein samples for Western blot analysis were extracted from WT mouse liver and kidney tissues and subjected to SDS PAGE by standard methods. The blotted membrane was processed for immunostaining as reported elsewhere [30]. Mouse and human TNALP were detected with rat anti-TNALP antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and a β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used for control purposes.

Purification of GPI-specific phospholipase D (GPI-PLD)

GPI-PLD was purified from commercially available human serum (Sigma). Serum was incubated with 9% polyethylene glycol for 1 hour, centrifuged at 2600 g for 15 minutes to remove insoluble materials. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, centrifuged through a Vivaspin 20 concentrator, MWCO 300 kDa (Vivascience AG, Hannover, Germany), concentrated with aquacide and dialyzed in “Buffer A” (i.e., 50 mM Tris, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.75). This solution was applied to a DEAE Sepharose column, eluated with 0.010–0.500 M NaCl (total volume 500 mL) in Buffer A. Each fraction was tested for GPI-PLD activity as reported elsewhere [19] and the fractions containing GPI-PLD was pooled, concentrated with aquacide and dialyzed in Buffer A. The solution containing GPI-PLD was applied to a Concanavalin A column and eluated with 0–1.0 M glucose in Buffer A. The fractions containing GPI-PLD was pooled, concentrated with aquacide, dialyzed with Buffer A and stored at 70°C.

Extraction and solubilization of ALP from tissues and organs

Tissue and organs were rinsed five to seven times with PBS at 4°C until no visible blood remained. ALP was extracted from the tissue/organs in isotonic saline with 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM benzamidine, 0.01 mg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 0.02% sodium azide for 72 h before centrifugation at 4000 g for 15 min as reported elsewhere [19]. GPI-PLD (approximately 2000 U/mL) was added to cleave ALP from insoluble membrane fragments to a final concentration of 25% together with 0.01% NP-40 and 5 μM zinc acetate and incubated for 16 h at 37°C with constant shaking. To separate the anchorless ALP from anchor-intact ALP, the preparation was incubated 1:1 with 20 mM Tris, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 20 μM zinc acetate and 4% Triton X-114, pH 8.3 for 30 min in a 37°C water bath and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min to separate the two phases. The upper phase containing anchorless ALP was collected and stored at −70°C until analysis.

Migration of ALP isozymes and isoforms in a native gel

Extracts from the different tissue samples (with and without neuraminidase) were separated on a Tris/glycine polyacrylamide gel 4–12%. The samples, 20 μL, were treated with 5 μL neuraminidase 20 U/mL in a 20 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.6 containing 20 μM zinc acetate, and incubated for 2 h in 37°C in a water bath. After electrophoresis, the samples were stained in the gel using 1.0 M 2-methyl-2-amino-1,3-propanediol buffer containing 3 mM MgCl2, 4.4 mM naphthyl phosphate and 1 g/L Variamine Blue RT salt (4-aminodiphenylamine diazonium sulphate).

Lectin precipitation

Extracts from the different tissue samples were incubated with Concanavalin A (Con A) from Canavalia Ensiformis (4 and 8 mg/mL), Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) from Triticum Vulgaris (1 and 3 mg/mL) or Peanut agglutinin (PNA) from Arachis hypogaea (2 and 5 mg/mL). Con A indicates terminal α-D-mannosyl and α-D-glucosyl residues; WGA, sialic acid and N-acetyl-glucosamine; and PNA, galactose-β(1–3)-N-acetylgalactosamine. Six aliquots of each tissue sample were incubated with each lectin, in a total volume of 0.1 mL for 30 min at 37°C. After precipitation, the samples were centrifuged at 7500 g for 10 min and the remaining ALP isoform activity was measured in the supernatant.

Heat inactivation and inhibition of ALP

Heat inactivation was performed at 56°C for 15 min and 65°C for 10 min [31] and the remaining ALP activity was measured. ALP was measured in tissue and serum samples in the presence of known inhibitors, i.e., 10 mM L-phenylalanine, 10 mM L-homoarginine, 100 μM tetramisole hydrochloride [32] and 3.3 M urea [33] in a total volume of 300 μL.

Chromatographic anion-exchange separation of mouse serum ALP

Sera from WT mice were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, diluted 1:1 with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.6 applied to a Blue Sepharose column and eluted with 0–0.25 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.6. The fractions containing ALP were pooled and applied to a Q-Sepharose column and eluted with 0.05–0.20 M sodium acetate (total volume 300 mL) in a buffer of 20 mM Tris and 10 μM zinc acetate at pH 7.6. Fractions, with approximately 3.0 mL, were collected and stored at 20°C until further analysis.

Results

HPLC analysis of ALP from mouse and human serum

Identical bone ALP isoforms (B/I, B1, and B2) were detected in mouse serum as in human serum (Fig. 1), but in addition, it was possible to detect the B1x bone isoform in mouse serum, which in humans has only been detected in patients with CKD and in human bone tissue [17–18]. Three liver ALP isoforms can normally be detected in human serum. A peak with ALP activity was detected with similar retention time as human liver ALP in mouse serum; however, subsequent experiments demonstrated that this peak was of intestinal origin (Alpi) and not of liver origin. The total ALP activity was not significantly lower in the Akp3−/− knockout mice in comparison with the Akp3+/+ WT mice. In the Akp3−/− mice all four bone ALP isoforms were detected, but the B/I peak that consists partly of dIALP was significantly lower compared with the WT mouse. A late peak was detected in both WT and Akp3−/− mice. Serum from the Alpi−/− mice contained the same isoforms as the WT mouse but the late peak was not detected. In the Alpl+/− mouse the same isoforms was detected as in the WT mouse but the peak area was about half of the peak area for the WT mouse. Some IALP activity was detected at retention times 5.32 min and 6.90 min for the Alpl−/− mouse, but other peaks were under the detection limit due to too low ALP activities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chromatographic ALP profiles of human serum, mouse serum, WT and knockout mouse serum. Total ALP activities, peak identities and retention times are as follows:

Human serum: Total ALP 2.0 μkat/L, B/I 4.88 min, B1 6.92 min, B2 10.47 min, L1 13.92 min, L2 16.05 and L3 17.93 min.

Mouse serum: Total ALP 3.6 μkat/L, B/I 4.87 min, B1x 5.95 min, B1 7.10 min, B2 10.28 min and IALP (Alpi) 16.72 min.

Akp3+/+: Total ALP 1.3 μkat/L, B/I 4.92 min, B1x 5.87 min, B1 6.72 min, B2 12.68 min and IALP (Alpi) 19.35.

Akp3−/−: Total ALP 1.7 μkat/L, B/I 4.93 min, B1x 5.87 min, B1 6.73 min, B2 12.23 min and IALP (Alpi) 19.13 min.

Alpi+/+: Total ALP 6.17 μkat/L, B1x (including B/I) 5.83 min, B1 7.03 min, B2 12.33 min and IALP (Alpi) 17.95 min.

Alpi−/−: Total ALP 3.9 μkat/L, B1x (including B/I) 5.85 min, B1 7.07 min and B2 12.20 min.

Alpl+/+: Total ALP 28.5 μkat/L, B/I 5.15 min, B1x 6.12 min, B1 7.63 min and B2 13.05 min.

Alpl+/−: Total ALP 13.2 μkat/L, B/I 5.12 min, B1x 6.27 min, B1 7.68 and B2 13.05 min.

Alpl−/−: Total ALP 0.05 μkat/L.

HPLC analysis of ALP from mouse tissue extracts

HPLC analysis of kidney tissue extracts demonstrated one early peak at the void volume and no later peaks. All the three bone tissue extractions (i.e., vertebra, femur and calvaria) contained four bone ALP isoforms B/I, B1x, B1 and B2 with retention times corresponding to the human bone ALP isoforms. Intestinal segments from WT mice revealed different fractions of IALP activity. Intestinal segment 1 (duodenum), with the foremost highest ALP activity, separated as three fractions, i.e., two minor peaks at 5.33 min and 6.95 min, and one major at 10.40 min. Intestinal segments 2, 3 (jejunum) and segment 4 (ileum) had one major peak at 11.60 min, but no earlier fractions with ALP activity. These results confirm that mice have more than one IALP isozyme and/or isoform (Fig. 2).

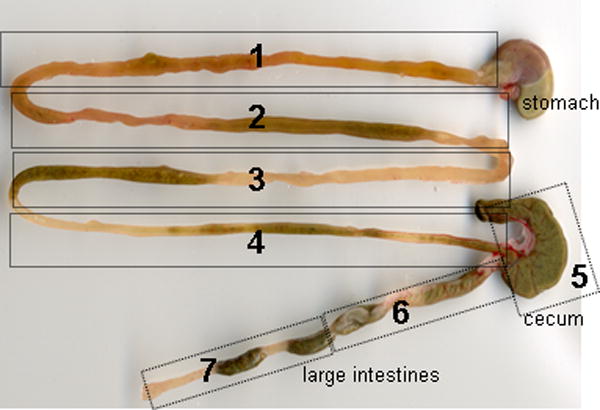

Fig. 2.

Chromatographic ALP profiles of tissue extracts from mouse intestinal segments. Total ALP activities and retention times are as follows: Segment 1 (duodenum): Total ALP 240 μkat/L, 5.33 min, 6.95 min and 10.40 min. Segment 2 (jejunum): Total ALP 39.8 μkat/L, 11.67 min. Segment 3 (jejunum): Total ALP 20.90 μkat/L, 11.43 min. Segment 4 (ileum): Total ALP 16.30 μkat/L, 11.62 min. These results confirm that mice have more than one IALP isozyme and/or isoform originating from the Akp3 and Alpi genes.

ALP in mouse tissue extracts

Significant amounts of ALP activity were extracted from all tissues except from the liver samples, which had remarkably low amounts of ALP activity (Fig. 3). Analysis of liver tissue extracts from four WT mice strains, i.e., C57Bl/6, BALB/c, FVB/N, and ICR (5 mice in each group), confirmed the low ALP activities ranging from 0.2 nkat/mg to 0.5 nkat/mg protein. The minimal detection limit for this analysis is 0.1 nkat/mg protein and the relation between the enzymatic activity units kat and U is 1000 nkat/L corresponds to 60 U/L. The ALP activity per mg protein (for tissues other than liver) ranged between 30 nkat/mg protein (calvaria and vertebra) to 100 nkat/mg protein (femur). In mouse intestine, ALP activity was found in all 7 intestinal segments but with very low activities in segments 6 and 7. The ALP activity ranged between 0.4 nkat/mg protein (segment 6 and 7) to 150 nkat/mg protein (segment 1) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(Top panel) ALP activities in pooled tissue extracts from 20 WT mice. (Middle panel) ALP activities in pooled tissue extracts from intestinal segments of 8 WT mice. (Bottom panel) Intestine of WT mouse. Segment 1 contains the major part of duodenum; segments 2 and 3 are jejunum; segment 4 is ileum; segment 5 is cecum; segments 6 and 7 contains colon.

ALP histochemical staining, Northern and Western blot analysis of WT mice strains

ALP histochemical staining of liver tissues from four WT mice strains and from ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) mice expressing human TNALP (used as positive control) are presented in Fig. 4. Some portal arteries in the portal triad showed ALP activity in all of the four strains analyzed. In C57Bl/6 and ICR mice, no ALP activity was detected in other cells, while in BALB/c and FVB/N mice, bile canaliculi showed faint but clear ALP activity. Hepatocytes of ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) were strongly positive as well as their bile canaliculi. These staining patterns were consistent within the five animals we analyzed for each strain and no recognizable variation was found among the individual mice.

Fig. 4.

ALP histochemical staining of liver tissues from four WT mice strains: (A, B) C57Bl/6; (C, D) BALB/c; (E, F) FVB/N; and (G, H) ICR. (I, J) ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) expressing human TNALP under control of a liver-specific promoter (positive control). Some portal arteries in the portal triad showed ALP activity in all of the four strains analyzed (black arrowheads). In C57Bl/6 and ICR mice, no ALP activity was detected in other cells, while in BALB/c and FVB/N mice, bile canaliculi showed faint but clear ALP activity (open arrowheads). Hepatocytes of ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) were strongly positive as well as their bile canaliculi. PV = portal vein. BD = Bile duct.

A, C, E, G and I: Scale bar 100 μm. B, D, F, H and J: Scale bar 50 μm.

Results from the Northern and Western blot analysis are presented in Fig. 5. The mouse TNALP gene was expressed at high levels in kidney and embryonic stem (ES) cells (used as positive control), while only trace amounts of mRNA were detected in the liver samples from each WT mice strain. Mouse TNALP was not detected significantly in liver samples from the four WT mice strains, while human TNALP was highly expressed in the liver from ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) mice and mouse TNALP was detected in normal kidney.

Fig. 5.

Northern and Western blot analysis of four WT mice strains. (Left panel) Northern blot analysis. Each lane was loaded with 20 μg of total RNA. Total RNA from D3 ES cells was included as a positive control. The mouse TNALP gene was expressed at high levels in kidney and ES cells, while only trace amounts of mRNA were detected in the liver samples. (Right panel) Western blot analysis. Each lane was loaded with 100 μg of protein except that the ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) sample was 75 μg. Mouse TNALP was not detected significantly in liver samples from the four WT mice strains, while human TNALP was highly expressed in the liver from ApoE-TNALP Tg (+) mice and mouse TNALP was detected in normal kidney.

Migration of ALP from mouse tissue extracts in a native gel

ALP from tissue extracts showed different migration patterns through a native gel, which indicates that they differ in charge and shape (Fig. 6). ALP from femur, vertebra and calvaria migrated a longer distance in the gel than the kidney and intestinal samples. After treatment with neuraminidase, all three bone samples migrated a more similar distance as the kidney and intestinal samples, which indicates that the differences in migration is due to terminal sialic acid residues.

Fig. 6.

Migration of ALP from mouse tissue extracts in a native gel. (A) kidney, (B) intestine, (C) femur, (D) vertebra, and (E) calvaria. * = ALP treated with neuraminidase prior to sample application. After treatment with neuraminidase, all three bone samples migrated a more similar distance as the kidney and intestinal samples, which indicates that the differences in migration is due to terminal sialic acid residues.

Lectin precipitation

The effect of dose-dependent lectin precipitation with WGA, Con A and PNA are shown in Fig. 7. WGA binds to sialic acid and N-acetyl-glucosamine. After incubation with 1 mg/mL WGA, intestinal and kidney samples were less precipitated than the different bone samples and serum, thus these isoforms do not contain as many sialic acid residues. The bone tissue extracts (vertebra, femur and calvaria) had residual ALP activities between 33–80% after WGA precipitation (1 mg/mL) and serum had 50% of remaining ALP activity. No further precipitation was observed with increasing WGA concentrations. Precipitation with Con A (4 mg/mL), that binds to terminal α-D-mannosyl and α-D-glycosyl residues, showed that all tissue extracts and mouse serum had remaining ALP activities between 43–66%. About the same results were observed with increasing Con A concentrations. ALP forms, that have the α-linked galactose terminally linked or β-galactose-(1-3)-N-acetylgalactosamine conjugated, are precipitated by PNA. PNA had little or no effect, 80–100% remaining ALP activity, on all the investigated tissue extracts and mouse serum.

Fig. 7.

Dose-dependent lectin precipitation on the different tissue samples; (◆) calvaria, (■) femur, (▲) vertebra, (×) intestine, (○) kidney, (●) serum. Each data point is expressed as a mean of six samples. (Top panel) WGA, 1 and 3 mg/mL; (middle panel) Con A, 4 and 8 mg/mL; (bottom panel) PNA, 2 and 5 mg/mL. These data show that circulating mouse serum consists of some IALP but mostly of bone ALP with terminal sialic acid residues.

Heat inactivation and inhibition of ALP activity

The results of the heat inactivation (56°C for 15 min and 65°C for 10 min) and the inhibitors (L-phenylalanine, L-homoarginine, tetramisole and urea) for the mouse serum and tissue extracts are presented in Fig. 8. In brief, heat inactivation at 65°C and L-phenylalanine had a substantial inhibitory effect on the intestine tissue extract and intestinal segments, whereas heat inactivation at 56°C, tetramisole, L-homoarginine, and urea had a larger inhibitory effect on the bone and kidney tissue extracts. The duodenum extracts (segment 1) were resistant to heat inactivation at 56°C, while intestinal segments 2, 3 and 4 (jejunum and ileum) lost 35–60% of there activity. Intestinal segments 5, 6 and 7 were not further investigated due to lack of ALP activity. Taken together, circulating mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP (including all four isoforms, B/I, B1x, B1, and B2) and IALP (including the two isozymes dIALP (Akp3) and gIALP (Alpi)), which is in agreement with the WT mouse serum HPLC profile in Fig. 1.

Fig. 8.

Heat inactivation of mouse tissue samples from pooled extract of 20 WT mice; incubation at 56°C for 10 min, and incubation at 65°C for 15 min. Inhibition with 100 μM tetramisole, 10 mM L-homoarginine, and 3.3 M urea and 10 mM L-phenylalanine. These data show that circulating mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP and some IALP, which is in agreement with the WT mouse serum HPLC profile in Fig. 1.

Chromatographic anion-exchange separation of mouse serum ALP

The yield of ALP activity after HPLC separation was too low to collect fractions from the investigated tissue samples for further analysis; therefore, a corresponding chromatographic anion-exchange (Q-Sepharose) method was developed to collect fractions containing ALP activity for subsequent inhibition studies of mouse serum. HPLC analysis of the late eluting peak (fraction 94 in Fig. 9), showed one single peak with a retention time corresponding to the late eluting peak for serum from mixed strains of WT mouse in Fig. 1. Inhibition analysis of this late eluting peak demonstrated that ALP in this fraction was inhibited by L-phenylalanine but not by tetramisole and L-homoarginine, thus demonstrating that this peak is of intestine origin. Taken together, and considering HPLC analysis of the Alpi+/+ and Alpi−/− knockout mice in Fig. 1, these results demonstrate that the late eluting peak during HPLC analysis of serum from WT mice is IALP originating from the Alpi gene.

Fig. 9.

Mouse serum ALP, from mixed strains of WT mice, separated on an anion-exchange Q-Sepharose column with a 0.05–0.2 M sodium acetate gradient. Fractions, with approximately 3.0 mL, were collected and analyzed with respect to ALP activity. HPLC analysis of the late eluting peak (fraction 94), showed one single peak with a retention time corresponding to the late eluting peak for serum from WT mouse (Fig. 1). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the late eluting peak from WT mice is IALP originating from the Alpi gene.

Discussion

Mouse serum ALP is frequently measured and interpreted in mammalian bone and mineral research, however; little is known about the circulating ALPs in mice and their correspondence to the human ALP isozymes and isoforms. The present work demonstrates that mice have identical bone ALP isoforms (B/I, B1x, B1, and B2) in serum as previously reported for humans [16]. Interestingly, the B1x bone isoform that has previously only been detected in patients with CKD and in human bone tissue [17–18] is present in WT mice. The human bone ALP isoforms have different catalytic properties due to structural differences in their posttranslational N-linked glycosylation [16]. Whatever biological significance of the variability in catalytic efficiencies for these bone isoforms might be, their occurrence seems to extend across mammalian species.

In agreement with the isoform profile revealed by HPLC, the lectin precipitation experiments also indicate that mice express different bone ALP isoforms with different anatomical distributions. The calvaria extracts precipitated differently to the applied lectins WGA, Con A and PNA, and this could be explained by different amounts of the detected bone ALP isoforms B/I, B1x, B1, and B2. Some anatomical differences have previously been reported in humans; cortical bone had approximately two-fold higher activity of B1 compared with B2 and, conversely, B2 was approximately two-fold higher in trabecular bone compared with B1 [19, 34].

In humans, the main sources of ALP are bone and liver. Despite numerous attempts with different extraction times and different WT mice strains, we could not extract any significant amounts of ALP from different WT mice strain livers, nor was any TNALP detectable by Western blot analysis. Histochemical staining confirmed the lack of ALP in WT mice hepatocytes for all strains except that some positive staining was detected in the bile canaliculi for BALB/c and FVB/N WT mice strains, which is in agreement with the previous findings of Hoshi et al. [35] who investigated the immunolocalization of TNALP in WT ddY mice. Only trace amounts of TNALP mRNA were detected in WT murine livers. These findings are important as it demonstrates that measuring ALP in mice is not informative when studying hepatocytes and liver function. The TNALP expression in bile canaliculi could, however, provide some information although that the expression varies with genetic background. Others have proclaimed liver ALP activity in mice, however, those results could be explained by decreased clearance rates of other ALP sources since ALP is cleared from the circulation by the hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptor [36]. Another explanation could be that the gIALP isozyme encoded by the Alpi gene has been erroneously interpreted as liver ALP activity. In mice, the gene coding for TNALP is named Alpl (i.e., the l denoting liver ALP), a nomenclature that should be reconsidered since WT mouse liver has undetectable amounts of ALP activity. We suggest the new gene nomenclature Alpb for mice and ALPB for humans, where the letter “b” denotes bone, which would be a more accurate classification concerning the genetic and physiological significance of ALP in bone in contrast to liver.

There is no immunoassay available to determine bone-specific ALP in mouse serum. In this study we show that serum consists mostly of bone ALP, including all four bone isoforms, and both IALP isozymes, i.e., dIALP (Akp3) and gIALP (Alpi), but no liver ALP. The major difficulty with available human bone-specific ALP immunoassays is the documented cross-reactivity between the bone and liver ALP isoforms, which is not surprising considering that they have identical protein cores and differ only by posttranslational glycosylation [37]. The recognized cross-reactivity would not be of concern during the development of mouse bone-specific ALP immunoassays since mice lack circulating liver ALP. Current commercially available monoclonal antibodies/immunoassays for human bone ALP have, however, no affinity for mouse bone ALP [8]. Our data should help to pave the way for the development of user-friendly assays measuring circulating bone-specific ALP in mice models used in bone and mineral research.

Our set of experiments, including histochemical staining, heat inactivation, inhibitors, lectins, HPLC, and Q-Sepharose anion-exchange chromatography on tissue extracts and serum from WT and knockout mice, are conclusive and demonstrates that the late eluting peak in HPLC analysis is gIALP encoded by the Alpi gene. The present work demonstrates also that different parts of the intestine (i.e., duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum and colon) have different amounts of IALP activity and, furthermore, HPLC analysis confirms our earlier data indicating that the IALP isozymes dIALP and gIALP are expressed differently throughout the intestine [30]. Duodenum (segment 1) had the highest activity and the activity decreased along the entire mouse intestine. HPLC analysis of the seven examined segments showed three different fractions in duodenum (segment 1), two early peaks and one later peak. Jejunum (segments 2 and 3) and ileum (segment 4) showed only the later peak. The later peak in these intestinal tissue extracts had the same retention time as the late peak appearing in the HPLC analysis of mouse serum (Fig. 1), i.e., the gIALP isozyme.

Results from the HPLC analysis of serum from Akp3 knockout mice show that the B/I peak decreased considerable in the Akp3 knockout mouse, indicating that this peak contain a large amount of dIALP. This corresponds to the early peak in the HPLC analysis of segment 1 and to the results by Narisawa and colleagues [30] who demonstrated that Akp3 is expressed in segment 1 but not in segments 2, 3 and 4 in WT mice. Akp3 was not detected in any intestinal tissue segments in Akp3 knockout mice, but Alpi was expressed in all segments. Akp3 starts expression at approximately day 15 day, but Alpi is expressed since embryonic stages. Our data indicate that when the Akp3 gene is knocked out, the expression of Alpi is upregulated, which is in agreement with previous qPCR, immunohistochemical and Western blot analysis [30].

Tetramisole and L-homoarginine inhibited ALP from mouse serum and intestine to a much lesser extent than ALP from bone and kidneys, whereas L-phenylalanine had a greater effect on ALP activities from intestine than serum, bone and kidney. Comparable inhibitory effects of these substances have been described for human ALP isozymes and isoforms [2]. Human IALP is more resistant to heat inactivation at 56°C, urea, tetramisole and L-homoarginine in comparison with the TNALP isozyme/isoforms. These results for mouse ALP can be explained by a difference in amino acid structure between TNALP and IALP [8], in addition to differences in glycosylation patterns as shown in the present study with the lectin precipitation experiments.

Differences were observed between mouse bone ALP and ALPs from kidney and intestine when tissue extract samples were run through a native gel. The difference between mouse bone ALP and IALP could be expected due to the difference in the amino acid structure, but the large difference between bone and kidney forms was not expected. As mentioned above, the kidney and bone isoforms of ALP are transcribed from the same gene, so the difference should probably be the difference in their glycosylation pattern. In humans, all ALP forms, except IALP, have sialic acids residues linked to them. Similar effects of neuraminidase could be observed on most mouse tissue extracts (Fig. 6). Neuraminidase had a large effect on bone ALP but, as expected, not on IALP. Furthermore, no effect was observed on kidney ALP after neuraminidase treatment, which reveals that both IALP and kidney ALP from mice lacks sialic acid residues.

In conclusion, the present work demonstrates that mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP, including all four bone ALP isoforms (B/I, B1x, B1, and B2), and both IALP isozymes, i.e., dIALP (Akp3) and gIALP (Alpi), but no liver ALP. In mice, the gene coding for TNALP is named Alpl (i.e., l stands for liver ALP), which should be reconsidered since WT mouse hepatocytes has insignificant amounts of TNALP mRNA and ALP activity as demonstrated by histochemical staining, Northern and Western blot analysis, and activity assays. We suggest the new gene nomenclature Alpb for mice and ALPB for humans, where the letter “b” denotes bone, which would be a more accurate classification concerning the genetic and physiological significance of ALP in bone in contrast to liver. Our data confirm the results of Narisawa el al. [30] that when the Akp3 gene is knocked out, the Alpi expression is upregulated. There is no immunoassay available to determine bone-specific ALP in mouse serum. The well-known cross-reactivity between human bone and liver ALP would not be of concern during the development of mouse bone-specific ALP immunoassays since mice do not have significant amounts of circulating liver ALP. Current commercially available monoclonal antibodies/immunoassays for human bone ALP have, however, no affinity for mouse bone ALP [8]. Our data should pave the way for the development of assays measuring circulating bone-specific ALP in mice models used in bone and mineral research. Whatever biological significance of the variability in catalytic efficiencies for these bone isoforms might be, their occurrence seems to extend across mammalian species.

Highlights.

ALP was extracted from mouse tissues. Serum from wild-type mice and different ALP knockout mouse models were also investigated

All mouse tissues, except liver and colon, contain significant ALP activity, which is surprising since human liver contains vast amounts of ALP

Mouse serum consists mostly of bone ALP (four bone ALP isoforms) and both intestinal ALP isozymes Akp3 and Alpi

These results should pave the way for the development of assays measuring bone-specific ALP in mouse serum

The bone ALP isoforms have variable catalytic efficiencies and their occurrence seems to extend across mammalian species

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the County Council of Östergötland in Sweden, and grant DE012889 from the National Institutes of Health, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McComb RB, Bowers GN, Jr, Posen S. Alkaline phosphatase. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millán JL. From biology to applications in medicine and biotechnology. Weinheim, Germany: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmgH & Co. KGaA; 2006. Mammalian alkaline phosphatase. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alatalo SL, Peng Z, Janckila AJ, Kaija H, Vihko P, Väänänen HK, et al. A novel immunoassay for the determination of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b from rat serum. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:134–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava AK, Bhattacharyya S, Castillo G, Miyakoshi N, Mohan S, Baylink DJ. Development and evaluation of C-telopeptide enzyme-linked immunoassay for measurement of bone resorption in mouse serum. Bone. 2000;27:529–33. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoegh-Andersen P, Tanko LB, Andersen TL, Lundberg CV, Mo JA, Heegaard AM, et al. Ovariectomized rats as a model of postmenopausal osteoarthritis: validation and application. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R169–80. doi: 10.1186/ar1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale LV, Sells Galvin RJ, Risteli J, Ma YL, Harvey AK, Yang X, et al. PINP: A serum biomarker of bone formation in the rat. Bone. 2007;40:1103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava AK, Castillo G, Wergedal JE, Mohan S, Baylink DJ. Development and application of a synthetic peptide-based osteocalcin assay for the measurement of bone formation in mouse serum. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:255–9. doi: 10.1007/s002230001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narisawa S, Harmey D, Magnusson P, Millán JL. Conserved epitopes in human and mouse tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Second report of the ISOBM TD-9 workshop. Tumour Biol. 2005;26:113–20. doi: 10.1159/000086482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava AK, Bhattacharyya S, Li X, Mohan S, Baylink DJ. Circadian and longitudinal variation of serum C-telopeptide, osteocalcin, and skeletal alkaline phosphatase in C3H/HeJ mice. Bone. 2001;29:361–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin D, Tucker DF, Gorman P, Sheer D, Spurr NK, Trowsdale J. The human placental alkaline phosphatase gene and related sequences map to chromosome 2 band q37. Ann Hum Genet. 1987;51:145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1987.tb01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith M, Weiss MJ, Griffin CA, Murray JC, Buetow KH, Emanuel BS, et al. Regional assignment of the gene for human liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase to chromosome 1p36. 1-p34. Genomics. 1988;2:139–43. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris H. The human alkaline phosphatases: what we know and what we don’t know. Clin Chim Acta. 1990;186:133–50. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90031-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnusson P, Degerblad M, Sääf M, Larsson L, Thorén M. Different responses of bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms during recombinant insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and during growth hormone therapy in adults with growth hormone deficiency. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:210–20. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosjean O, Koyama I, Goseki M, Roux B, Komoda T. Human tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatases: sugar-moiety-induced enzymic and antigenic modulations and genetic aspects. Biochem J. 1997;321:297–303. doi: 10.1042/bj3210297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnusson P, Farley JR. Differences in sialic acid residues among bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms: a physical, biochemical, and immunological characterization. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;71:508–18. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halling Linder C, Narisawa S, Millán JL, Magnusson P. Glycosylation differences contribute to distinct catalytic properties among bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms. Bone. 2009;45:987–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnusson P, Sharp CA, Magnusson M, Risteli J, Davie MW, Larsson L. Effect of chronic renal failure on bone turnover and bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms. Kidney Int. 2001;60:257–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haarhaus M, Fernström A, Magnusson M, Magnusson P. Clinical significance of bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms, including the novel B1x isoform, in mild to moderate chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3382–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnusson P, Sharp CA, Farley JR. Different distributions of human bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms in serum and bone tissue extracts. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;325:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishman L, Miyayama H, Driscoll SG, Fishman WH. Developmental phase-specific alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes of human placenta and thier occurrence in human cancer. Cancer Res. 1976;36:2268–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narisawa S, Hasegawa H, Watanabe K, Millán JL. Stage-specific expression of alkaline phosphatase during neural development in the mouse. Dev Dyn. 1994;201:227–35. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002010306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahnel AC, Rappolee DA, Millán JL, Manes T, Ziomek CA, Theodosiou NG, et al. Two alkaline phosphatase genes are expressed during early development in the mouse embryo. Development. 1990;110:555–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narisawa S, Fröhlander N, Millán JL. Inactivation of two mouse alkaline phosphatase genes and establishment of a model of infantile hypophosphatasia. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:432–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<432::AID-AJA13>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manes T, Glade K, Ziomek CA, Millán JL. Genomic structure and comparison of mouse tissue-specific alkaline phosphatase genes. Genomics. 1990;8:541–54. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90042-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waymire KG, Mahuren JD, Jaje JM, Guilarte TR, Coburn SP, MacGregor GR. Mice lacking tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase die from seizures due to defective metabolism of vitamin B-6. Nat Genet. 1995;11:45–51. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millan JL, McKee MD, Karsenty G. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1093–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnusson P, Löfman O, Larsson L. Methodological aspects on separation and reaction conditions of bone and liver alkaline phosphatase isoform analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:156–63. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnusson P, Löfman O, Larsson L. Determination of alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes in serum by high-performance liquid chromatography with post-column reaction detection. J Chromatogr. 1992;576:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80177-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, et al. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narisawa S, Hoylaerts MF, Doctor KS, Fukuda MN, Alpers DH, Millán JL. A novel phosphatase upregulated in Akp3 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1068–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00073.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss DW, Whitby LG. A simplified heat-inactivation method for investigating alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes in serum. Clin Chim Acta. 1975;61:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(75)90398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishman WH, Sie HG. Organ-specific inhibition of human alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes of liver, bone, intestine and placenta; L-phenylalanine, L-tryptophan and L homoarginine. Enzymologia. 1971;41:141–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahr M, Wilkinson JH. Urea as a selective inhibitor of human tissue alkaline phosphatases. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;17:367–70. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magnusson P, Larsson L, Magnusson M, Davie MW, Sharp CA. Isoforms of bone alkaline phosphatase: characterization and origin in human trabecular and cortical bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1926–33. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoshi K, Amizuka N, Oda K, Ikehara Y, Ozawa H. Immunolocalization of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase in mice. Histochem Cell Biol. 1997;107:183–91. doi: 10.1007/s004180050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blom E, Ali MM, Mortensen B, Huseby N-E. Elimination of alkaline phosphatases from circulation by the galactose receptor. Different isoforms are cleared at various rates. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;270:125–37. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magnusson P, Ärlestig L, Paus E, Di Mauro S, Testa MP, Stigbrand T, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Report of the ISOBM TD9 workshop. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:228–48. doi: 10.1159/000067254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]