Abstract

The extracellular domain of M2 (M2e), a small ion channel membrane protein, is well conserved among different human influenza A virus strains. To improve the protective efficacy of M2e vaccines, we genetically engineered a tandem repeat of M2e epitope sequences (M2e5x) of human, swine, and avian origin influenza A viruses, which was expressed in a membrane-anchored form and incorporated in virus-like particles (VLPs). The M2e5x protein with the transmembrane domain of hemagglutinin (HA) was effectively incorporated into VLPs at a several 100-fold higher level than that on influenza virions. Intramuscular immunization with M2e5x VLP vaccines was highly effective in inducing M2e-specific antibodies reactive to different influenza viruses, mucosal and systemic immune responses, and cross-protection regardless of influenza virus subtypes in the absence of adjuvant. Importantly, immune sera were found to be sufficient for conferring protection in naive mice, which was long-lived and cross-protective. Thus, molecular designing and presenting M2e immunogens on VLPs provide a promising platform for developing universal influenza vaccines without using adjuvants.

Introduction

Influenza virus is a respiratory pathogen with a segmented negative sense RNA genome, belonging to the family of the Orthomyxoviridae. Influenza virus can cause ~250,000 deaths worldwide annually and a global pandemic could kill millions.1,2 Influenza viruses are continuously evolving, resulting in numerous variants with distinct antigenic surface glycoprotein properties in part due to diverse natural reservoirs including wild birds, chickens, pigs, and humans. On the basis of antigenic differences in the surface proteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase, 16 HA (H1-H16) and 9 neuraminidase (N1-N9) glycoprotein subtypes have been identified in influenza A viruses.3 Vaccination is the most cost-effective measure to prevent influenza disease and its mortality.2 However, there is a limitation of the current vaccines because the antigenic regions of HA are highly susceptible to continuous mutation in circulating epidemic virus strains.4,5 Thus, it is a high priority to develop vaccines inducing broadly cross-protective immunity to different strains of influenza virus.

The influenza A virus M2 protein remains nearly invariant among different strains,6 suggesting that M2 would be a promising candidate antigen for developing universal influenza vaccines. Previous studies have focused on influenza A vaccines based on the small extracellular domain of M2 (M2e), attempting to develop more universal vaccines. Due to poor immunogenicity of the small M2e, various approaches were applied to fuse M2e peptides to carrier proteins or vehicles. Representative carrier molecules or systems include hepatitis B virus core particles,7,8,9,10 human papillomavirus L proteins,11 phage Qβ-derived protein cores,12 keyhole limpet hemocyanin,13 bacterial outer membrane complexes,8,14 liposomes,15 cholera toxin subunit,16 and flagellin.17,18 These M2e conjugate vaccines were used for multiple immunizations of mice, together with potent adjuvants such as complete or incomplete Freund's adjuvant,8,13,19 cholera toxin subunits,20 monophosphoryl lipid A,15,16 or heat-labile endotoxin.7,21,22,23,24 In these previous studies, M2e genetic or chemical conjugate vaccines in the presence of strong adjuvants provided survival protection followed by significant loss in body weight after lethal challenge. M2-based vaccines would be efficacious if their immunogenicity and protective potency should be improved.

The concept of recombinant influenza vaccines based on virus-like particles (VLPs) has been reported by several research groups.25,26,27,28,29 A recent study described influenza M1-derived VLPs containing the wild-type M2 protein (M2WT VLPs) in a membrane-anchored form.30 However, the M2WT VLP vaccines suffered from low levels of M2 proteins incorporated into VLPs and a weak protective efficacy. In an effort to generate recombinant tetrameric M2e vaccines, genetic fusion of M2e to the oligomerization domain of general control nondepressible 4 was reported.31 Nonetheless, this M2e-general control nondepressible 4 vaccine still required the use of adjuvants (monophosphoryl lipid A, Alhydrogel, or cholera toxin subunits).31

In the present study, we genetically engineered a new construct with a tandem repeat of M2e sequences (M2e5x) derived from human, swine, and avian origin influenza A viruses to better cover a broader range of influenza viruses. The M2e5x construct was expressed on a VLP platform in a membrane-anchored form (M2e5x VLPs). Humoral and cellular immunogenicity as well as cross-protective efficacy of M2e5x VLP vaccines were investigated after intramuscular immunization.

Results

Preparation of VLPs containing tandem repeat M2e

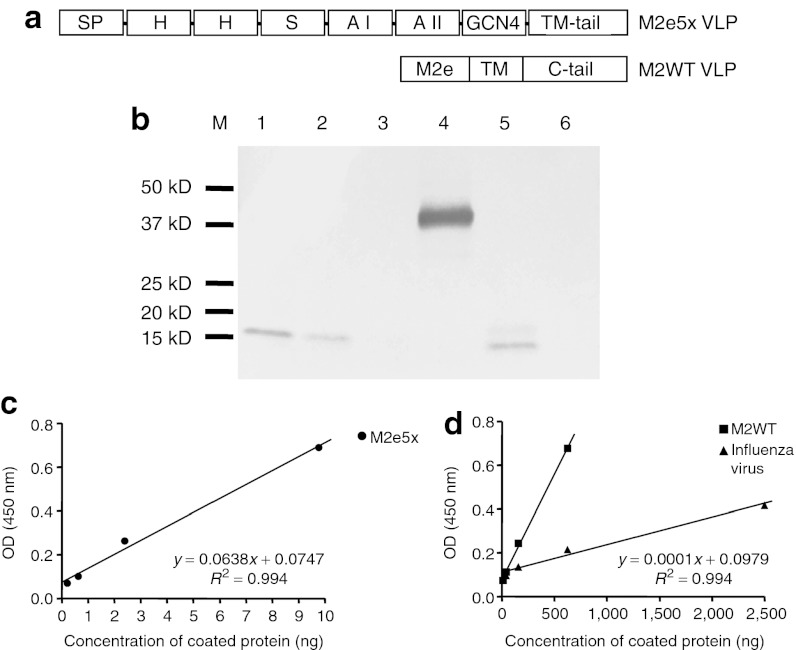

To improve M2 VLP vaccines, a new M2 construct was designed at a molecular level and genetically constructed. A tandem repeat of M2e (M2e5x) was introduced to increase the density and variation of M2e epitopes. The M2e5x is composed of heterologous M2e sequences including conserved sequences derived from human, swine, and avian origin influenza A viruses (Figure 1a). Also, a domain (general control nondepressible 4) known to stabilize oligomer formation was linked to the C-terminal part of M2e5x. The signal peptide from the honeybee protein melittin was added to the N-terminus of M2e5x for efficient expression on insect cell surfaces, thus enhancing incorporation into VLPs.32 Finally, the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail domains were replaced with those derived from HA of A/PR/8/34 virus to increase the incorporation into VLPs (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Characterization of tandem repeat M2e5x and M2WT VLPs. (a) Structures of M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP. SP: melittin signal peptide, H: Human influenza A type M2e, S: Swine influenza A type M2e, A I: Avian influenza A type I M2e, A II: Avian influenza A type II M2e, TM-tail: A/PR8 hemagglutinin transmembrane and tail domains, -: linker. (b) Western blot of influenza H3N2 virus, M2e5x, and M2WT VLPs using mouse anti-M2 monoclonal antibody (14C2). Lanes 1–3: influenza A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2) virus (10, 5, and 1 µg, respectively), Lane 4: M2e5x VLP (100 ng), Lane 5: M2WT VLP (1 µg), and Lane 6: negative (VLPs without M2). M2 reactivity to (c) M2e5x VLP and (d) M2WT VLP and influenza A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2) virus was calculated by ELISA using M2 monoclonal antibody (Abcam 14C2). kD, kilodalton; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; OD, optical density; TM, transmembrane; VLP, virus-like particles.

M2e5x VLPs produced in Sf9 insect cells were found to incorporate M2e proteins into VLPs ~60- to over 100-fold higher levels than the M2WT VLP and influenza virus as determined by western blot using anti-M2 monoclonal antibody 14C2 (Figure 1b). For quantitative comparison of M2e epitopes in VLP vaccines or virus, we compared M2e-specific monoclonal antibody reactivity by ELISA using M2e5x and M2WT VLPs and influenza virus (Figure 1c,d). It was estimated that the reactivity of M2e monoclonal antibody 14C2 to M2e5x VLP was at least 60-fold higher than that to M2WT VLP. Compared with that of A/Philippines/2/82 virus, the reactivity of 14C2 M2 antibody to M2e5x VLP was ~500-fold higher (Figure 1c,d). The M2 antibody 14C2 reactivity to M2e5x VLP was not increased by membrane-disrupting detergent treatment (data not shown), indicating the reactivity to the surface-expressed M2e epitopes on VLPs. These results suggest that the tandem repeat of heterologous M2e may be presented on the VLPs in a conformation highly reactive to M2e-recognizing antibody 14C2.

M2e5x VLPs induce M2e-specific antibody responses

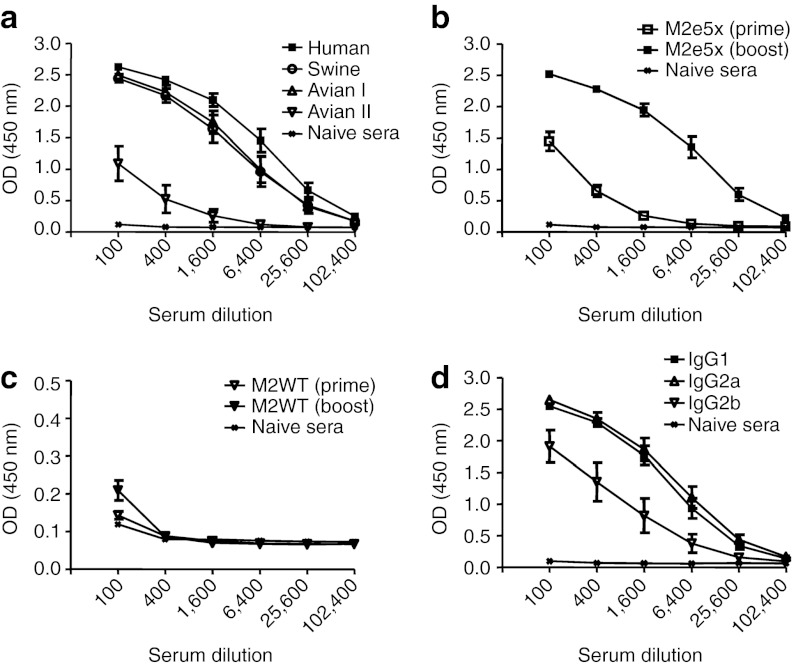

Although the M2 ectodomain (M2e) is highly conserved among human influenza A strains, there are some amino acid replacements in the swine or avian origin influenza viruses.6 Thus, we tested whether M2e5x VLP immune sera would be reactive with M2e peptide sequences of swine or avian influenza A virus (Figure 2). Immune sera collected from mice boosted with M2e5x VLPs showed substantial levels of antibody reactivity to swine and avian type I M2e peptides (Figure 2a). The reactivity to the avian type II M2e peptide was found to be lower than others. This low reactivity might be due to the fact that the avian type II peptide epitope is located at the most proximal region to the membrane in the M2e5x construct (Figure 1a). The reactivity to human type M2e peptide antigen was approximately twofold higher than the other types, probably due to its most external location, implicating positional effects on immunogenicity.

Figure 2.

M2e-specific total IgG and IgG isotype antibody responses. BALB/c mice (N = 8) were immunized with 10 µg of M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP. (a) Peptide-specific ELISA. IgG antibodies specific to M2e were measured in boost immune sera using human, swine, avian I, or avian II type peptide as a coating antigen. (b,c) Total IgG antibody. IgG was detected by the human type M2e peptide as an ELISA-coating antigen to (b) M2e5x VLP and (c) M2WT VLP-immunized sera. (d) IgG isotype responses. (b–d) Sera were serially diluted and ELISA was performed for serum antibodies specific to human type peptide. Error bars indicates mean ± SEM. M2e, extracellular domain of M2; OD, optical density; VLP, virus-like particles.

To determine the immunogenicity of influenza VLPs containing M2e5x and M2WT proteins, groups of mice (eight BALB/c mice per group) were intramuscularly immunized with 10 µg of VLPs twice at weeks 0 and 4. Levels of M2e-specific IgG antibodies were analyzed in immune sera by ELISA using an M2e peptide antigen that is highly conserved among human influenza A viruses. At 3 weeks after priming, M2e-specific antibodies were detected at significant levels in the group of mice immunized with M2e5x VLPs (Figure 2b). In contrast, immunization with M2WT VLPs induced only marginal levels of M2e-specific antibodies (Figure 2c). After boost immunization, antibodies specific to M2e were observed at significantly increased levels, over 60-fold higher compared with those observed after priming in the M2e5x VLP group (Figure 2b). The M2WT VLPs were not highly effective in inducing boost immune responses (Figure 2c).

When we determined IgG isotypes (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b) specific to M2e peptide antigen, the level of IgG1 was found to be similar to that of IgG2a in boost immune sera (Figure 2d). Also, IgG2b isotype antibody was observed at a substantial level. Thus, M2e5x VLP vaccines seem to be effective in inducing balanced IgG1 and IgG2a as well as IgG2b antibody responses.

M2e5x VLP-induced antibody is cross-reactive with different influenza viruses

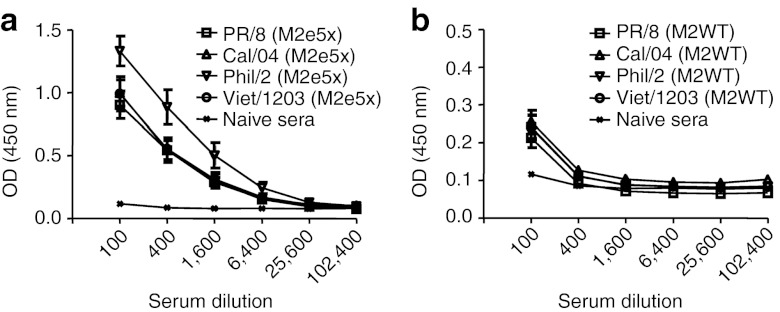

It is important to determine the reactivity of M2e-specific antibodies to different strains of influenza viruses, which may provide correlative insight into the efficacy of cross-protection. We used whole inactivated virus A/California/4/2009 (H1N1), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2), and A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) as ELISA-coating antigens (Figure 3). Immune sera showed high levels of antibody responses cross-reactive to virus particles (Figure 3a). Cross-reactivity to A/Philippines/2/82 virus was approximately fourfold higher than that to the swine origin A/California/2009 virus or other viruses which showed similar binding properties to M2e5x VLP boost immune sera (Figure 3a). In contrast, M2WT VLP immune sera showed low levels of reactivity to viral antigens although these levels were higher than naive sera (Figure 3b). Therefore, these results suggest that M2e5x VLPs are highly immunogenic and capable of inducing antibodies reactive to influenza A virions in the absence of adjuvant regardless of HA subtype.

Figure 3.

IgG antibody responses reactive to influenza viruses. Inactivated influenza viruses, A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), A/California/4/2009 (H1N1), A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2), and reassortant A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1), were used as coating antigen for antibody detection. (a) M2e5x VLP-immunized sera (N = 8). (b) M2WT VLP-immunized sera (N = 8). Sera were collected 3 weeks after prime boost vaccination. Serum was serially diluted and ELISA was performed. Error bars indicates mean ± SEM. a and b are in different scales in the Y-axis due to significant differences in optical density values of antibody responses between M2e5x and M2WT VLP immune sera (P < 0.01). M2e, extracellular domain of M2; OD, optical density; VLP, virus-like particles.

M2e5x VLPs provide protection against both H3N2 and H1N1 viruses

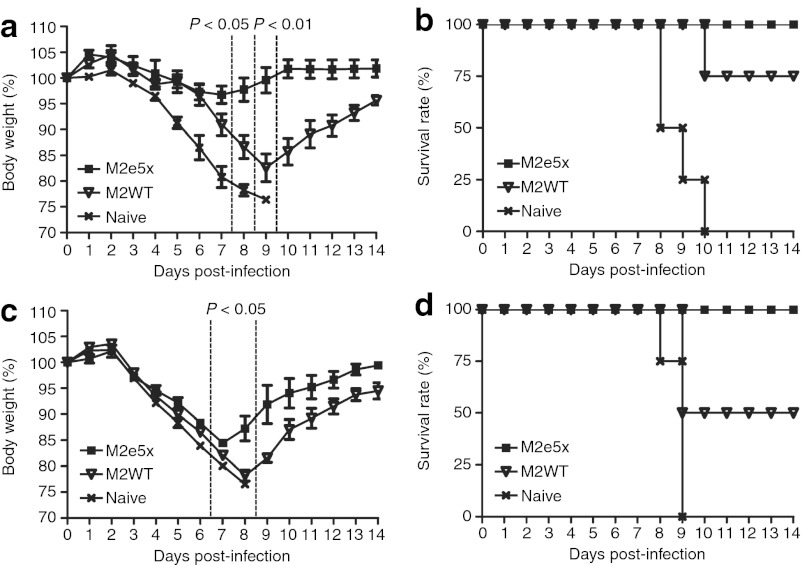

To compare the efficacy of M2e5x VLPs with that of M2WT VLPs in conferring protection against lethal challenge infection, groups of mice were intramuscularly immunized and challenged with a lethal dose (LD) of A/Philippines/82 (H3N2) and A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) influenza viruses at 6 weeks after boosting (Figure 4). In the A/Philippines/2/82 protection experiment, the body weight changes and survival rates were monitored following challenge infection. All naive mice lost over 25% in body weight and had to be euthanized (Figure 4). The M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice showed a slight loss in body weight post-challenge and then recovered to the normal body weight, resulting in 100% protection (Figure 4a). In contrast, M2WT VLP-vaccinated mice showed a significant loss of ~17% in body weight as well as a substantial delay in recovering body weight (Figure 4a). The M2WT VLP group showed 75% protection against lethal challenge with A/Philippines H3N2 virus (Figure 4b). The M2e5x VLP group also showed 100% survival after lethal challenge with A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) influenza virus (Figure 4c,d). Despite a body weight loss of 15%, all mice recovered to normal body weight in the M2e5x VLP group (Figure 4c). However, the M2WT VLP group showed ~22% body weight loss and only a survival rate of 50%, and a delay in recovery of body weight after lethal challenge with A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) influenza virus (Figure 4c,d). These results demonstrate that M2e5x VLPs are superior to M2WT VLPs in conferring cross-protection after intramuscular vaccination.

Figure 4.

M2e5x VLP vaccination induces improved cross-protection. At 6 weeks after boost vaccination, groups of mice (N = 4) were challenged with a lethal dose (4xLD50) of influenza viruses.(a,b) A/Philippines/2/82(H3N2). (c,d) A/California/4/2009 (H1N1). (a,c) Average body weight changes and (b,d) survival rates were monitored for 14 days. Error bars indicates SEM. P value indicates significant difference between M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP groups. LD, lethal dose; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; VLP, virus-like particles.

Intramuscular immunization with M2e5x VLPs induces mucosal antibodies

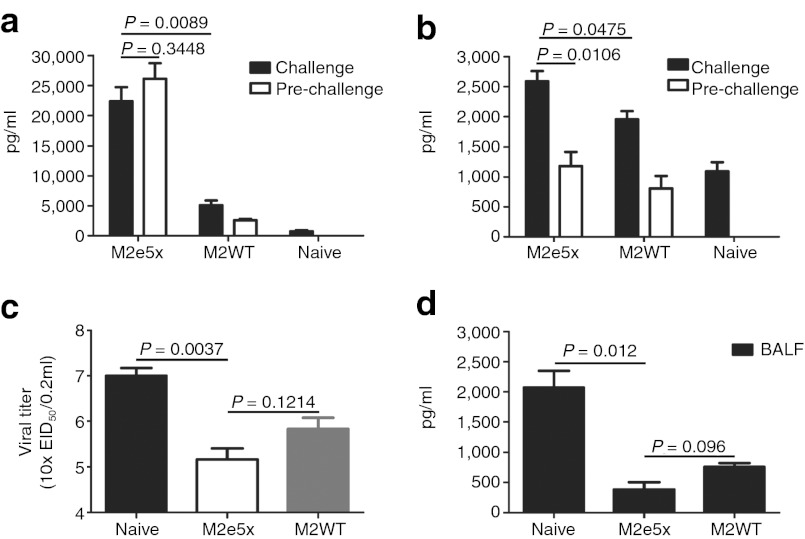

Mucosal immunity is important for conferring protection against influenza virus. We therefore determined M2e-specific IgG and IgA antibody responses in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) (Figure 5a,b). Significant levels of IgG antibody responses specific to M2e were observed in BALF in M2e5x VLP-immunized mice pre-challenge and at day 5 post-challenge (A/Philippines/2/82 virus) (Figure 5a). M2WT VLP group showed low levels of IgG antibodies recognizing M2e antigen pre-challenge and at day 5 post-challenge. Interestingly, a rapid increase in IgA antibodies specific to M2e peptide was observed in BALF post-challenge compared with those in pre-challenge of vaccinated mice (Figure 5b). As expected, both mucosal IgG and IgA antibody responses in the M2e5x VLP group were significantly higher than those in M2WT group (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Antibody responses, virus, and inflammatory cytokine levels in lungs after challenge. Levels of IgG and IgA antibodies were determined in samples collected from M2e5x VLP- or M2WT VLP-immunized mice pre-challenged or at day 5 post-challenge with 4xLD50 of A/Philippines/2/83 (H3N2) virus (N = 3). (a) IgG antibody level in BALF. (b) IgA antibody level in BALF. The antibody level was determined by ELISA using human type M2e peptide as a coating antigen. Lung viral titers and IL-6 cytokine in BALF were determined from M2e5x VLP- or M2WT VLP-immunized mice at day 5 after challenge with 4xLD50 of A/Philippines/2/83 (H3N2) virus (N = 3). (c) Lung viral titers were determined by an egg inoculation assay. (d) IL-6 in BALF. IL-6 was determined by a cytokine ELISA. Data represent mean ± SEM. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; EID, egg infectious dose; IL, interleukin; IM, intramuscular; LD, lethal dose; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; pg, picogram; VLP, virus-like particles.

M2e5x VLP vaccination lowers lung viral titers and inflammatory cytokine levels

To better assess the protective efficacy against A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2), lung viral titers were determined at day 5 after challenge. The group of mice intramuscularly immunized with M2e5x VLPs showed approximately fourfold and 100-fold lower lung viral titers (A/Philippines/2/82 virus) compared with those in the M2WT VLP and naive-challenge control group, respectively (Figure 5c). Therefore, it is likely that M2e-specific immune responses in systemic and mucosal sites can effectively contribute to controlling virus replication after intramuscular immunization.

Proinflammatory cytokines are involved in causing tissue damage, which may lead to death. Cytokines in BALF from M2e5x VLP- or M2WT VLP-immunized mice after challenge were determined (Figure 5d). Significantly higher levels of interleukin (IL)-6 were observed in BALF from naive mice infected with A/Philippines/2/82 virus than M2e5x VLP- or M2WT VLP-immunized mice, indicating lung inflammatory responses probably due to high viral replication (Figure 5d). Therefore, these results indicate that modulation of cytokine production as a result of M2e5x VLP immunization plays a role in improving cross-protection upon lethal challenge.

M2e5x VLPs are an effective vaccine for inducing M2e-specific recall T-cell responses

T-cell responses are known to contribute to broadening cross-protective immunity. After in vitro stimulation of cells with an M2e-specific peptide, cytokine-producing spots of lymphocytes from spleens and lungs were measured as an indicator of T-cell responses (Figure 6). Mice were challenged with A/Philippines/2/82 virus at 8 weeks after boost and cells from tissues were collected before challenge or at day 5 post-challenge to determine recall immune responses of M2e-specific T cells. Over 30-fold higher levels of interferon (IFN)-γ–secreting spleen cells were observed in the M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice compared with those in the M2WT VLP or naive group (Figure 6a). Also, ~17-fold increased levels of IFN-γ–secreting cell spots were observed after challenge compared with those in pre-challenge or naive (Figure 6a). The M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice showed threefold higher levels of IL-4–secreting cell spots than groups of M2WT or infected naive mice (Figure 6b). Also, in lung cells, spot numbers of IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting cells were detected at twofold higher levels in M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice than those in M2WT VLP-vaccinated mice (Figure 6c,d). Compared with those in pre-challenge, M2e5x VLP- and M2WT-vaccinated mice showed 70- and 20-fold increases in IFN-γ–secreting lung cell spots, respectively (Figure 6c). Significant increases in IL-4–secreting lung cell spots were observed after challenge of vaccinated mice but not in naive-challenged mice (Figure 6d). Importantly, the M2WT VLP group showed substantial levels of IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting cell spots in mucosal tissue cells compared with the naive-infected control (Figure 6c,d). It is interesting to note that spots of IFN-γ were higher than those of IL-4 in lung cells (Figure 6c,d) whereas the reverse pattern was observed with spleen cells (Figure 6a,b). However, decreased levels of IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting cells were observed in pre-challenged mice and significant increases of IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting cells were observed in spleen and lung cells of challenged mice when compared with pre-challenged mice (Figure 6). These results provide evidence that M2e5x VLP immunization more effectively induced M2e-specific IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting T-cell recall responses in spleens and lung cells compared with M2WT VLP vaccination.

Figure 6.

Enhanced anamnestic cellular immune responses by M2e5x VLP vaccination. (a) IFN-γ–secreting cells in splenocytes (N = 6). (b) IL-4–secreting cells in splenocytes (N = 6). (c) IFN-γ–secreting cells in lung cells. (d) IL-4–secreting cells in lung cells. Splenocytes and lung cells were isolated from mice pre-challenge or at day 5 post-challenge. Cytokine-producing cell spots were counted by ELISPOT reader. Data represent mean ± SEM. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; VLP, virus-like particles.

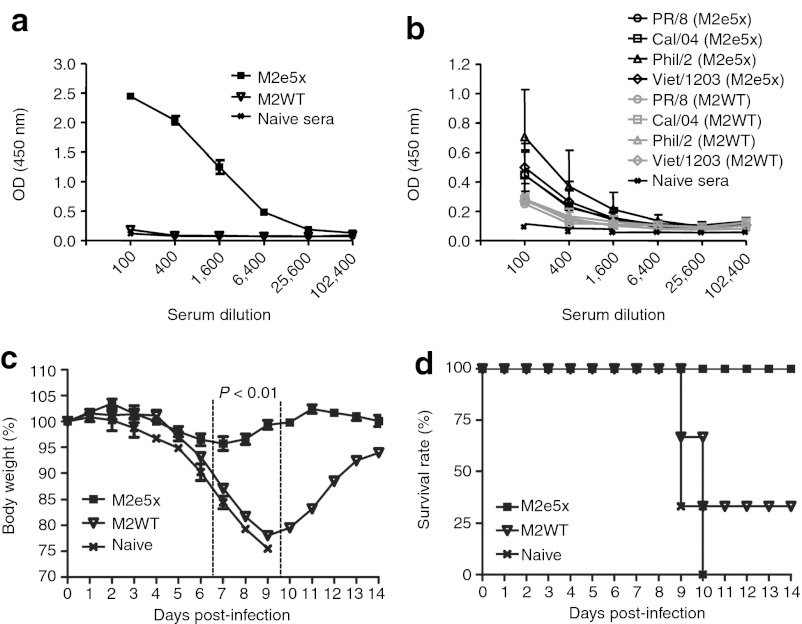

M2e5x immunity is long-lived

One of the goals for vaccination is to induce long-term protective immunity. Thus, we determined the longevity of M2e antibody responses induced by M2e5x VLP vaccination. The M2e-specific antibody responses to M2e5x-immunized sera were maintained at significantly high levels (Figure 7a) and influenza virus M2-specific antibody responses were also maintained at higher levels than that of M2WT VLPs (Figure 7b) for over 8 months, indicating that M2 immunity can be long-lived. To assess the long-term protective efficacy, groups of mice that were intramuscularly immunized with M2e5x or M2WT VLPs were challenged with a LD of A/Philippines/82 (Figure 7c,d) at 8 months after vaccination. Mice that were immunized with M2e5x VLPs (10 µg of total protein) using a prime boost regimen were 100% protected without significant weight loss (Figure 7c,d). However, a group of mice that was immunized with M2WT VLPs (10 µg of total protein) was only 33% protected, and accompanied by severe weight loss up to 22% in surviving mice (Figure 7d). These results indicate that M2e5x VLP vaccines are more effective in inducing long-lasting protection against mortality as well as morbidity after intramuscular immunization.

Figure 7.

M2e5x VLP vaccination induces long-term protection. (a) M2e peptide and (b) influenza virus-specific IgG antibody responses in sera at 8 months after boost immunizations (N = 3). (c) Body weight changes and (d) survival rates after challenge with 4xLD50 of influenza A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2) virus (N = 3). Data represent mean ± SEM. P value indicates a significant difference between M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP groups. LD, lethal dose; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; OD, optical density; VLP, virus-like particles.

M2e5x VLP immune sera play an important role in conferring protection

To further determine the protective role of anti-M2e5x or M2WT immune sera, we carried out an in vivo protection assay. Naive mice were infected with a mixture of immune sera and a LD of different strains of influenza A virus. Immune sera collected at different timepoints, 3 weeks (Figure 8a,b) or 8 months (Figure 8c,d) were used to assess the cross-protective effect of M2 immune sera. In addition, to test the breadth of cross-protection, we extended the protection studies to the following viruses, A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) reassortant virus and A/PR8/34 (H1N1). Naive mouse sera and M2WT VLP immune sera did not confer any protection to mice (Figure 8). In contrast, M2e5x VLP immune sera provided 100% protection to naive mice that were infected with a LD of A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (Figure 8a) or A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) reassortant virus (Figure 8b). Low levels of morbidity (5–10% weight loss) were observed in protected mice. With sera from M2e5x VLP-immunized mice collected at 8 months after boost, naive mice were 100% protected against A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (Figure 8c) or reassortant A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus (Figure 8d). Body weight loss was in the range of 10–18% depending on the virus strain used for infection, implying that these surviving mice experienced more morbidity compared to those treated with M2e5x VLP immune sera collected at 3 weeks after boost (Figure 8a,b). Nonetheless, these results further support the evidence that M2e5x VLP vaccination can induce antibody responses which confer long-term protective immunity to different subtypes of influenza viruses. Therefore, VLPs with a tandem repeat of M2e sequences from multiple strains are a promising universal vaccine candidate compared with the M2WT VLP vaccine.

Figure 8.

M2e5x VLP immune sera confer protection to naive mice. Mice (N = 4) were intranasally infected with 4xLD50 of influenza virus mixed with immune sera (M2e5x or M2WT VLP) or naive sera. Immune sera collected from vaccinated mice at (a,b) 3 weeks and (c,d) 8 months after boost immunization were incubated with influenza viruses, (a,c) A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) and (b,d) reassortant A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1). Body weight and survival rates were monitored for 14 days. P value indicates significant difference between M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP groups. LD, lethal dose; M2e, extracellular domain of M2; VLP, virus-like particles.

Discussion

In this study, we designed and constructed a new influenza M2e5x VLP that contains tandem repeats of M2e consisting of heterologous M2e sequences from multiple strains in a membrane-anchored form. There are few amino acid changes in residues 10-23 of M2e, depending on host species where influenza viruses are isolated.6,23 Thus, an additional strategy was introduced into the M2e5x construct to enhance the breadth of cross-protection by including M2e sequences originated from influenza A viruses of swine and avian species. We found that the heterologous tandem repeats of M2e on VLPs was capable of broadening and extending cross-reactivity after vaccination. Immune sera to M2e5x VLP vaccination were cross-reactive to M2e peptide sequences of swine and avian origins in addition to the human type. This new M2e5x construct with an HA-derived transmembrane domain was found to be incorporated into VLPs at a much higher level compared with the M2 levels in whole influenza virus particles. M2e5x VLP construct described in this study significantly improved the immunogenicity and efficacy compared with M2WT VLP. Therefore, molecular engineering of an M2e vaccine construct and presenting it on VLPs is a promising platform for presenting viral vaccine antigens and developing an effective vaccine.

Intramuscular administration is the common route of influenza vaccination in humans. However, it is known to be difficult to induce heterosubtypic cross-protection by intramuscular immunization with nonreplicating subunit vaccines. Heterosubtypic protection was observed with inactivated influenza virus vaccines in the presence of endotoxin mucosal adjuvants via intranasal immunization but not via intramuscular immunization.33,34 Intranasal immunization with nonreplicating or inactivated subunit vaccines has not been approved for human use yet and its efficacy in humans remain unknown. In clinical studies, some side effects were reported to be associated with intranasal influenza vaccination with an inactivated virosomal vaccine.35,36 Thus, it is highly significant to demonstrate heterosubtypic cross-protection after intramuscular immunization with molecularly designed M2e5x VLP vaccines.

A new approach was applied in the current study to present tandem repeats of M2e on VLPs in a membrane-anchored form, mimicking its native-like conformation because M2 is a membrane protein. The M2e5x VLPs were highly immunogenic and able to induce broad cross-protection in the absence of adjuvants. This is in contrast to previous studies reporting chemical or genetic fusion of M2e to carrier vaccines with multiple immunizations at high doses of M2e vaccines in the presence of potent adjuvants inappropriate for human use. In particular, immune sera to M2e5x VLP vaccination showed cross-reactivity to different strains of influenza virus particles. Protection was observed in the A/Philippines/2/82 H3N2 virus challenge with less body weight loss (~5%), which might be due to the high reactivity of M2e5x VLP immune sera to that virus. Antibodies induced by M2e conjugate vaccines such as M2e-hepatitis B virus core were not able to effectively bind to virus particles despite having high titers to M2e peptide antigens, which may be correlated with weak protection by M2e-hepatitis B virus core immunization.10 It is speculated that cross-reactive binding of antibody to virus is likely to play a role for providing protection. Importantly, long-term protection even after 8 months post-vaccination was observed without significant morbidity (Figure 7c,d). This is a highly encouraging result in a hope toward developing broadly cross-protective influenza vaccines based on conserved M2 immunity via a genetically engineered VLP platform.

Protective immune correlates have not been well understood after influenza M2 vaccination. Serum antibodies specific to M2e were shown to play an important role in providing protection as evidenced by effects of M2e5x VLP immune sera on conferring protection in naive mice (Figure 8). Previous studies demonstrated that alveolar dendritic and macrophage cells,30 and natural killer cells10 were shown to be important for M2e antibody-mediated protection. A recent study also demonstrated that Fc receptors are important for anti-M2e IgG-mediated immune protection.37 Consistent with this previous study, we also observed that Fc receptor was an important immune mediator for conferring protection by M2 immune sera as shown using a Fc receptor knockout mouse model (data not shown). In contrast to antibodies specific to influenza HA proteins, anti-M2 antibodies were reported not to have direct virus neutralizing and hemagglutination inhibition activities.10,38 Protection by non-neutralizing anti-influenza humoral immunity was dependent on opsonophagocytosis of influenza virions by macrophages.39,40,41,42 Therefore, it is suggested that induction of virus-binding antibodies by M2 VLP vaccination contributes to viral clearance, possibly via opsonizing virus by macrophages and dendritic cells through Fc receptors. Levels of serum antibodies reactive to a virus would provide a correlation predicting cross-protection.

There is also a possibility that mucosal immune responses and IFN-γ–secreting T-cell responses induced by intramuscular immunization with M2e5x VLPs contributed to improving the protection against viral challenge infection. We observed significant levels of BALF IgG antibodies but not IgA antibody in the group of M2e5x VLP immunization even before challenge (Figure 5a,b). However, BALF IgA antibodies were rapidly increased to high levels at an early timepoint day 5 post-challenge. Thus, these results suggest that intramuscular vaccination with an immunogenic vaccine such as M2e5x VLPs can prime mucosal immunity, which was shown to induce rapid recall mucosal immunity upon exposure to a pathogen. It is also interesting to note that high levels of spleen and particularly lung cells secreting IFN-γ were rapidly induced at day 5 post-challenge (Figure 6). Therefore, in addition to serum antibodies specific to M2e, it is likely that multiple systemic and mucosal immune parameters contribute to cross-protection after M2e5x VLP intramuscular immunization.

In summary, this study demonstrates several important advances in the field toward developing M2-based universal influenza vaccines. (i) Heterologous tandem repeats of M2e epitope sequences (M2e5x) genetically designed to be expressed in a membrane-anchored form were effectively incorporated into VLPs at a much higher level than that on influenza virions or M2WT VLPs. (ii) Intramuscular immunization with M2e5x VLP vaccines was proven to be effective in inducing cross-protection regardless of HA subtypes. (iii) Immune sera to M2e5x VLP vaccination were highly reactive to influenza virions and sufficient to transfer cross-protection to naive mice. (iv) This protection was achieved in the absence of adjuvant. (v) Intramuscular immunization with M2e5x VLP vaccines was able to elicit antibodies in mucosal sites and IFN-γ–secreting cellular immune responses upon viral challenge. (vi) This cross-protection was found to be long-lived without significant signs of disease. Thus, genetically designed M2e5x VLP vaccines could be more effective in inducing M2e immune responses than live virus infection. As for future directions, it will be important to better understand the immune mechanisms of M2 immune-mediated protection. Results in this study provide evidence that molecular design and genetic engineering approaches would have the potential to develop new M2e VLP vaccines inducing broad cross-protection against human and possibly swine and avian origin influenza viruses.

Materials and Methods

Cells, viruses, and reagents. Spodoptera frugiperda sf9 insect cells (CRL-1711; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in SF900-II serum-free medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 27 °C and used for production of recombinant baculoviruses and VLPs. Ten-days-old embryonated chicken eggs were used for virus propagation and viral titration. Influenza A viruses, A/California/4/2009 (2009 pandemic H1N1 virus) was kindly provided by Richard Webby, mouse-adapted A/Philippines/2/1982 (H3N2) and A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) were generously provided by Huan Nguyen. Reassortant H5N1 virus HA and neuraminidase derived from A/Vietnam/1203/2004, and the remaining backbone genes from A/PR/8/34 virus as described.43 Inactivation of the purified virus was performed by mixing the virus with formalin at a final concentration of 1:4,000 (vol/vol).44 Genes for five tandem repeats of M2 ectodomain (M2e5x) and four sets of M2e peptide (a2-20), human type-SLLTEVETPIRNEWGSRSN, swine type-SLLTEVETPTRSEWESRSS, avian I type-SLLTEVETPTRNEWESRSS, and avian II type-SLLTEVETLTRNGWGCRCS were chemically synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ), and used in this study.

Preparation of M2e5x VLP. M2WT VLPs with influenza matrix protein M1 were prepared as described.30 A synthesized DNA fragment of M2e5x construct was cloned into the pFastBac vector plasmid which was subsequently used to make recombinant Bacmid baculovirus DNAs (rAcNPV) using DH10Bac competent cells (Invitrogen). A recombinant baculovirus expressing M2e5x was generated by transfection of sf9 insect cells following the manufacturer's instruction. To produce influenza VLPs containing M2e5x protein, recombinant baculoviruses expressing M1 and M2e5x protein were coinfected into sf9 insect cells at multiplicity of infection of 1:2. At 2 days after infection, the infected cell culture supernatants were clarified by centrifugation (6,000 rpm, 30 minutes) and then were concentrated by the QuixStand hollow fiber-based ultrafiltration system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). M2e5x VLPs were purified by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation with layers of 20 and 60% (wt/vol) as previously described.30 Influenza A virus M2 monoclonal antibody 14C2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used for detection of M2e5x protein by western blot.

Immunization and challenge. For animal experiments, 10 µg (total protein) of M2e5x VLP or M2WT VLP was dissolved in 100 µl of phosphate-buffered saline and used to intramuscularly immunize each 6–8-weeks-old female BALB/c mouse (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) at a 4-week interval. Three weeks after prime or boost immunization, mice were bled to test immune responses. Six weeks after boost immunization, mice (n = 8) were challenged with 4xLD50 (50% mouse LD50) of A/Philippines/2/82 (H3N2) and A/California/4/2009 (H1N1) influenza viruses. To determine the long-term protective efficacy, additional groups of mice (N = 3) were challenged with a LD (4xLD50) of A/Philippines/2/82 influenza virus 8 months after boost vaccination. Mice were monitored daily to record weight changes and mortality (25% loss in body weight as the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) endpoint). Full details of this study and all animal experiments presented in this manuscript were approved by the Emory University and Georgia State University (GSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee review boards (approval nos. 179-2008 and A11026, respectively). Approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols operate under the federal Animal Welfare Law (administered by the US Department of Agriculture) and regulations of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Determination of antibody responses. M2e-specific serum antibody responses were determined by ELISA using synthetic human, swine, avian I, and avian II type M2e peptides or inactivated purified virions (4 µg/ml) as a coating antigen as previously described.30 Briefly, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, or IgG2a were used as secondary antibodies to determine total IgG or IgG isotype antibodies. The substrate TMB (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was used to develop color and 1 mol/l H3PO4 was used to stop developing color reaction. The optical density at 450 nm was read using an ELISA reader.

Preparation of BALF and lung extracts. Lung tissues were isolated from mice pre-challenged or killed at day 5 post-challenge with influenza A/Philippines/2/1982 (H3N2) virus. Lung extracts were prepared using a mechanical tissue grinder with 1.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline per each lung and viral titers were determined using 10-days-old embryonated chicken eggs.45 Lung cells were recovered from mechanically grinded lung samples by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 5 minutes) for the determination of T-cell response. BALF were obtained by infusing 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline using a 25-gauge catheter (Exelint International, Los Angeles, CA) into the lungs via the trachea, and used for antibody response.

Determination of T-cell responses. Splenocytes and lung cells were isolated from mice pre-challenge or at day 5 post-challenge and single cell suspensions were prepared as described.46 IFN-γ– and IL-4–secreting cell spots were determined on Multi-screen 96 well plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) coated with cytokine-specific capture antibodies as described.47 Briefly, 0.5 × 106 spleen cells per well and 0.2 × 106 lung cells were cultured with M2e human type peptide (2 µg/ml) as an antigenic stimulator. After 36 hours of incubation, the spots of IFN-γ– or IL-4–secreting T cells were counted using an ELISpot reader (Biosys, Miami, FL).

Cross-protective efficacy test of immune sera. To test cross-protective efficacy of immune sera in vivo, serum samples were collected from mice immunized with M2e5x VLP and M2WT VLP on 3 weeks and 8 months after boost immunization. Four or eight times diluted sera were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 minutes and the serum samples were mixed with same volume of 8xLD50 of influenza virus and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes as described.44 A mixture (4xLD50) of a lethal infectious dose of A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) or A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) influenza virus with sera was administered to naive mice (N = 4, BALB/c), and body weight and survival rates were monitored daily.

Statistical analysis. To determine the statistical significance, a two-tailed Student's t-test was used when comparing two different conditions. A P value <0.05 is considered to be significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI0680003 (R.W.C.), AI093772 (S.-M.K.), and AI087782 (S.-M.K.), and Animal, Plant, and Fisheries Quarantine Inspection Agency grant (I-1541781-2012-15-01), Republic of Korea. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Viboud C, Miller M, Olson D, Osterholm M., and, Simonsen L. Preliminary Estimates of Mortality and Years of Life Lost Associated with the 2009 A/H1N1 Pandemic in the US and Comparison with Past Influenza Seasons. PLoS Curr. 2010;2:RRN1153. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholm MT. Preparing for the next pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1839–1842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Munster V, Wallensten A, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Smith D.et al. (2005Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls J Virol 792814–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush RM, Bender CA, Subbarao K, Cox NJ., and, Fitch WM. Predicting the evolution of human influenza A. Science. 1999;286:1921–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin JB., and, Dushoff J. Codon bias and frequency-dependent selection on the hemagglutinin epitopes of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7152–7157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132114100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zou P, Ding J, Lu Y., and, Chen YH. Sequence comparison between the extracellular domain of M2 protein human and avian influenza A virus provides new information for bivalent influenza vaccine design. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neirynck S, Deroo T, Saelens X, Vanlandschoot P, Jou WM., and, Fiers W. A universal influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of the M2 protein. Nat Med. 1999;5:1157–1163. doi: 10.1038/13484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Liang X, Horton MS, Perry HC, Citron MP, Heidecker GJ.et al. (2004Preclinical study of influenza virus A M2 peptide conjugate vaccines in mice, ferrets, and rhesus monkeys Vaccine 222993–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filette M, Fiers W, Martens W, Birkett A, Ramne A, Löwenadler B.et al. (2006Improved design and intranasal delivery of an M2e-based human influenza A vaccine Vaccine 246597–6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T., and, Bachmann MF. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol. 2004;172:5598–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu RM, Przysiecki CT, Liang X, Garsky VM, Fan J, Wang B.et al. (2006Pharmaceutical and immunological evaluation of human papillomavirus virus-like particle as an antigen carrier J Pharm Sci 9570–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessa J, Schmitz N, Hinton HJ, Schwarz K, Jegerlehner A., and, Bachmann MF. Efficient induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by virus-like particles administered intranasally: implications for vaccine design. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:114–126. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins SM, Zhao ZS, Lo CY, Misplon JA, Liu T, Ye Z.et al. (2007Matrix protein 2 vaccination and protection against influenza viruses, including subtype H5N1 Emerging Infect Dis 13426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu TM, Grimm KM, Citron MP, Freed DC, Fan J, Keller PM.et al. (2009Comparative immunogenicity evaluations of influenza A virus M2 peptide as recombinant virus like particle or conjugate vaccines in mice and monkeys Vaccine 271440–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst WA, Kim HJ, Tumpey TM, Jansen AD, Tai W, Cramer DV.et al. (2006Protection against H1, H5, H6 and H9 influenza A infection with liposomal matrix 2 epitope vaccines Vaccine 245158–5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson DG, El Bakkouri K, Schön K, Ramne A, Festjens E, Löwenadler B.et al. (2008CTA1-M2e-DD: a novel mucosal adjuvant targeted influenza vaccine Vaccine 261243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huleatt JW, Nakaar V, Desai P, Huang Y, Hewitt D, Jacobs A.et al. (2008Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin Vaccine 26201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley CB, Rupp RE, Johnson C, Taylor DN, Wolfson J, Tussey L.et al. (2011Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant M2e-flagellin influenza vaccine (STF2.4xM2e) in healthy adults Vaccine 295145–5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Yuan XY, Li J., and, Chen YH. The co-administration of CpG-ODN influenced protective activity of influenza M2e vaccine. Vaccine. 2009;27:4320–4324. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Peng Z, Liu Z, Lu Y, Ding J., and, Chen YH. High epitope density in a single recombinant protein molecule of the extracellular domain of influenza A virus M2 protein significantly enhances protective immunity. Vaccine. 2004;23:366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filette M, Min Jou W, Birkett A, Lyons K, Schultz B, Tonkyro A.et al. (2005Universal influenza A vaccine: optimization of M2-based constructs Virology 337149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen PP, Rijsewijk FA, de Boer-Luijtze EA., and, Bianchi AT. Vaccination of pigs with a DNA construct expressing an influenza virus M2-nucleoprotein fusion protein exacerbates disease after challenge with influenza A virus. J Gen Virol. 2002;83 Pt 8:1851–1859. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers W, De Filette M, Birkett A, Neirynck S., and, Min Jou W. A “universal” human influenza A vaccine. Virus Res. 2004;103:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filette M, Ramne A, Birkett A, Lycke N, Löwenadler B, Min Jou W.et al. (2006The universal influenza vaccine M2e-HBc administered intranasally in combination with the adjuvant CTA1-DD provides complete protection Vaccine 24544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarza JM, Latham T., and, Cupo A. Virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine conferred complete protection against a lethal influenza virus challenge. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:244–251. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushko P, Tumpey TM, Bu F, Knell J, Robinson R., and, Smith G. Influenza virus-like particles comprised of the HA, NA, and M1 proteins of H9N2 influenza virus induce protective immune responses in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2005;23:5751–5759. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright RA, Carter DM, Daniluk S, Toapanta FR, Ahmad A, Gavrilov V.et al. (2007Influenza virus-like particles elicit broader immune responses than whole virion inactivated influenza virus or recombinant hemagglutinin Vaccine 253871–3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan FS, Huang C, Compans RW., and, Kang SM. Virus-like particle vaccine induces protective immunity against homologous and heterologous strains of influenza virus. J Virol. 2007;81:3514–3524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02052-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JR, Dokken L, Wiley JA, Cawthon AG, Bigger J, Harmsen AG.et al. (2009Influenza-pseudotyped Gag virus-like particle vaccines provide broad protection against highly pathogenic avian influenza challenge Vaccine 27530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JM, Wang BZ, Park KM, Van Rooijen N, Quan FS, Kim MC.et al. (2011Influenza virus-like particles containing M2 induce broadly cross protective immunity PLoS ONE 6e14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filette M, Martens W, Roose K, Deroo T, Vervalle F, Bentahir M.et al. (2008An influenza A vaccine based on tetrameric ectodomain of matrix protein 2 J Biol Chem 28311382–11387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang BZ, Liu W, Kang SM, Alam M, Huang C, Ye L.et al. (2007Incorporation of high levels of chimeric human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins into virus-like particles J Virol 8110869–10878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada A, Matsushita S, Ninomiya A, Kawaoka Y., and, Kida H. Intranasal immunization with formalin-inactivated virus vaccine induces a broad spectrum of heterosubtypic immunity against influenza A virus infection in mice. Vaccine. 2003;21:3212–3218. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Renshaw M, Clements JD., and, Katz JM. Mucosal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine induces B-cell-dependent heterosubtypic cross-protection against lethal influenza A H5N1 virus infection. J Virol. 2001;75:5141–5150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5141-5150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendi P, Locher R, Bucheli B., and, Battegay M. Intranasal influenza vaccine in a working population. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:974–980. doi: 10.1086/386330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendi P, Locher R, Bucheli B., and, Battegay M. The decision to get vaccinated against influenza. Am J Med. 2004;116:856–858. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bakkouri K, Descamps F, De Filette M, Smet A, Festjens E, Birkett A.et al. (2011Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection J Immunol 1861022–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JM, Van Rooijen N, Bozja J, Compans RW., and, Kang SM. Vaccination inducing broad and improved cross protection against multiple subtypes of influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:757–761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber VC, Lynch JM, Bucher DJ, Le J., and, Metzger DW. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis makes a significant contribution to clearance of influenza virus infections. J Immunol. 2001;166:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber VC, McKeon RM, Brackin MN, Miller LA, Keating R, Brown SA.et al. (2006Distinct contributions of vaccine-induced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a antibodies to protective immunity against influenza Clin Vaccine Immunol 13981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozdzanowska K, Feng J, Eid M, Zharikova D., and, Gerhard W. Enhancement of neutralizing activity of influenza virus-specific antibodies by serum components. Virology. 2006;352:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasekera JP, Moseman EA., and, Carroll MC. Natural antibody and complement mediate neutralization of influenza virus in the absence of prior immunity. J Virol. 2007;81:3487–3494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02128-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JM, Kim YC, Barlow PG, Hossain MJ, Park KM, Donis RO.et al. (2010Improved protection against avian influenza H5N1 virus by a single vaccination with virus-like particles in skin using microneedles Antiviral Res 88244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan FS, Compans RW, Nguyen HH., and, Kang SM. Induction of heterosubtypic immunity to influenza virus by intranasal immunization. J Virol. 2008;82:1350–1359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01615-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEN HS., and, WANG SP. Mouse adaptation of the Asian influenza virus. J Infect Dis. 1959;105:9–17. doi: 10.1093/infdis/105.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan FS, Kim YC, Yoo DG, Compans RW, Prausnitz MR., and, Kang SM. Stabilization of influenza vaccine enhances protection by microneedle delivery in the mouse skin. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JM, Hossain J, Yoo DG, Lipatov AS, Davis CT, Quan FS.et al. (2010Protective immunity against H5N1 influenza virus by a single dose vaccination with virus-like particles Virology 405165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]