Abstract

Laypeople and many social scientists assume that superior reasoning abilities lead to greater well-being. However, previous research has been inconclusive. This may be because prior investigators used operationalizations of reasoning that favored analytic as opposed to wise thinking. We assessed wisdom in terms of the degree to which people use various pragmatic schemas to deal with social conflicts. With a random sample of Americans we found that wise reasoning is associated with greater life satisfaction, less negative affect, better social relationships, less depressive rumination, more positive vs. negative words used in speech, and greater longevity. The relationship between wise reasoning and well-being held even when controlling for socio-economic factors, verbal abilities, and several personality traits. As in prior work there was no association between intelligence and well-being. Further, wise reasoning mediated age-related differences in well-being, particularly among the middle-aged and older adults. Implications for research on reasoning, well-being and aging are discussed.

Keywords: affect, aging, intelligence, reasoning, well-being, wisdom

The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts (Marcus Antonius, 1891).

Scholars since at least the time of Aristotle have speculated that superior reasoning leads to greater well-being. This is consistent with laypeople’s intuitions and beliefs about themselves — those people who report greater well-being believe that they have superior reasoning abilities (Campbell, Converse, & Rogers, 1976; Study 3; Diener & Fujita, 1995). However, various large-scale studies have shown no relationship between standard measures of intelligence and well-being (e. g. Sigelman, 1981; Watten, Syversen, & Myhrer, 1995; Wirthwein & Rost, 2011). Furthermore, abstract reasoning abilities and other types of fluid intelligence decline over adulthood (Salthouse, 2004), yet older adults report greater well-being than their younger counterparts (e.g. Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). Moreover, standard intelligence tests do not do a good job of capturing people’s ability to think about social relations (e.g. Sternberg, 1999) or real-world decision-making (e.g. Stanovich, 2009).

We propose that superior reasoning may in fact be related to well-being, but that this is true for pragmatic (as opposed to abstract) reasoning. By pragmatic reasoning we mean reasoning that is influenced by life experiences and situated in a social context. Such reasoning strategies have been described as “wise” by both philosophers and psychologists. Although wisdom has been defined in many ways (Sternberg & Jordan, 2005), there is some consensus that wisdom involves the use of certain types of pragmatic reasoning that are prosocial, and which helps to navigate important challenges in social life. For instance, Baltes and colleagues (Baltes & Smith, 2008) — who developed the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm — have defined wisdom as knowledge useful for dealing with life problems, including an awareness of the varied contexts of life and how they change over time, recognition that values and goals differ among people, and acknowledgment of the uncertainties of life (together with ways to manage these uncertainties). Similarly, Basseches (1980) and Kramer (1983) — representing the neo-Piagetian view of reasoning — formulated a set of cognitive schemas they believed to be involved in wise thinking, including: acknowledgment of others’ points of view, appreciation of contexts broader than the issue at hand, sensitivity to the possibility of change in social relations, acknowledgment of the likelihood of multiple outcomes of a conflict, concern with conflict resolution, and preference for compromise of opposing viewpoints.

Little work has directly tested the relationship between wise reasoning and well-being. The only two studies that we are aware of that have examined this question used the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm. These studies found inconclusive results. In one study wise reasoning was unrelated to negative affect1, but it was weakly positively related to some aspects of positive affect (e.g. feeling interested or inspired; Kunzmann & Baltes, 2003). In another study wise reasoning was unrelated to people’s positive or negative emotional responses, but negatively related to global judgment of life satisfaction (particularly among top 15 % on wise reasoning; Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). It is important to consider that the materials in these studies included rather abstract descriptions of personal problems. For instance, participants were asked to read and respond to such scenarios as “a14-year-old girl wants to move away from home right away” or “somebody gets a phone call from a good friend. The friend says that she or he cannot go on anymore and that she or he has decided to commit suicide” (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000). Such briefly-described scenarios provided little information about social context, which may be a critical factor in the assessment of wise reasoning (Sternberg, 2004). Thus, it remained unclear if wisdom-related forms of reasoning are linked with well-being. The present work aimed to fill this gap in the literature by using a novel measure of wise reasoning to systematically investigate the relationship to a large number of well-being indicators.

We built on the idea that people acquire wisdom through experience and through successful mastery of various challenging life experiences (Pascual-Leone, 1990; Rowley & Slack, 2009; Sternberg, 1998). Such experiences are heterogeneous in nature, and may result in idiosyncratic ways of thinking about conflict. Therefore, and consistent with the process-oriented view of wisdom (Kramer, 2000; Sternberg, 1998), we conceptualized wisdom as a set of reasoning strategies that may be applicable and beneficial across a large number of social conflicts. In other words, we defined wisdom not through the availability of static knowledge about a particular conflict and its solution, but rather through the use of dynamic reasoning strategies that can be applied in various domains. Building on earlier theoretical work conceptualizing wisdom as an inherently social construct (Rowley, 2006; Sternberg, 2007), we measured wisdom using naturalistic, context-rich materials concerning social conflicts and by examining reasoning in a structured interview with a researcher.

We measured six broad strategies of wise reasoning in our content analyses of participants’ responses to social dilemmas (Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Basseches, 1980; Kramer, 1983; Staudinger & Glück, 2011). These components were: (i) considering the perspectives of people involved in the conflict; (ii) recognizing the likelihood of change; (iii) recognizing multiple ways in which the conflict might unfold; (iv) recognizing uncertainty and the limits of knowledge; (v) recognizing the importance of / searching for a compromise between opposing viewpoints; and (vi) recognizing the importance of / predicting conflict resolution. The validity of these dimensions as measures of wise reasoning has been demonstrated in a recent study, which surveyed a large pool of wisdom researchers and counseling practitioners. The results from this study indicated that wisdom researchers and practitioners rated responses that are high on these dimensions as wiser than those that were low on these dimensions (Grossmann et al., 2010; Study 3).

Overview of the Present Research

In order to address the relationship between wise reasoning and well-being, we measured wise reasoning about real world intergroup and interpersonal dilemmas and various indicators of well-being. To maximize the possibility of detecting conditions under which wise reasoning may or may not be related to well-being, we tested a diverse set of socio-emotional tasks. In addition to exploring the relationship between wise reasoning and well-being, we also addressed the question of how aging impacts this relationship. Specifically, we predicted that older adults would show greater well-being, partly because they are wiser than younger adults when reasoning about social conflicts (Grossmann, et al., 2010; Studies 1–2; Worthy, Gorlick, Pacheco, Schnyer, & Maddox, 2011).

Materials and Methods

Participants

We recruited a stratified random sample of 241 Americans in Washtenaw county, Michigan, with an approximately equal number of participants of both genders, and of each of three age groups (25–40, 41–59, 60–90), and an adequate number of adults from lower educated strata (see Table 1). Participants were informed that we were interested in human reasoning and they were compensated with $70 for taking part in each of the two 2-hour individual experimental sessions.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

| Demographic category | %/ M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 50.9% female |

| Age | 49.48 (16.65) |

| Age group | |

| 25–40 | 38.2% |

| 41–59 | 28.9% |

| 60–90 | 32.9% |

| African American | 12.3% |

| Asian American | 3.5% |

| European American | 80.26% |

| Latino | 3.9% |

| Education | |

| high school or less | 27.90% |

| some college | 11.50% |

| college / post- | 30.30% |

| secondary | 58.20% |

| Family income | |

| under $40,000 | 29.6 |

| $40,000–60,000 | 19.7 |

| $60,000–80,000 | 20.2 |

| over $80,000 | 30.5 |

Procedure and materials

Wise reasoning

Part of the data on wise reasoning came from the Michigan Wisdom Study (Grossmann, et al., 2010). The qualitative part of the study was conducted in a face-to-face interview setting of the Robert Zajonc laboratory at the Institute for Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI. Participants were informed that we are interested in people’s reasoning about various future events. Care was taken to ensure that the setting does not induce fear of cognitive ability testing and possible ageism-related stereotype threat (Hess & Blanchard-Fields, 1999). Specifically, the test setting aimed to provide a social atmosphere (e.g. use of a meeting room instead of a laboratory cubicle, neutral art pictures on the walls of the room), and the wisdom-related stimulus materials were formatted as regular newspaper articles. Further, the interview was conducted using a semi-structured procedure and involved additional probes to each question. In session 1 participants read three newspaper articles describing intergroup tensions (over ethnic differences, politics, and natural resources) in unfamiliar countries (Grossmann et al., in press; Grossmann, et al., 2010). After each story the interviewer instructed participants to talk about the future development of the conflict, guided by three questions in the following order: “What do you think will happen after that?”, “Anything else?” and “Why do you think it will happen this way?” Participants’ responses were audio-recorded. In session 2 participants read three letters describing interpersonal dilemmas (between friends, spouses, and neighbors) selected from the “Dear Abby” advice column. Participants then answered questions similar to those used in session 1. These tasks lasted 30 minutes per session on average.

Coding procedure

Participants’ transcripts were masked, and age-related information was removed. Two hypothesis-blind coders were trained on sample materials until they reached high inter-rater reliability. These coders then scored transcripts of each response on the six aspects of wise reasoning: i) considering the perspective of the parties involved; (ii) recognizing the likelihood of change; (iii) recognizing multiple possibilities regarding how a conflict might unfold; (iv) recognizing limits of one’s own knowledge and acknowledging uncertainty; (v) searching for compromise; and (vi) predicting conflict resolution. Raters coded participants’ transcripts on a scale from 1 = “not at all” to 3 = “a great deal”; see Table 1 for example responses. In order to increase the external validity of these ratings, we employed separate groups of raters for intergroup and interpersonal scenarios. Agreement between two respective raters was good (inter-rater rs ≥ .85; coder discrepancies resolved in group discussion between the coders and the first author). Considering the diverse nature of the scenarios, scores across various scenarios showed acceptable reliability as indicated by internal consistency and intra-class correlation measures (session 1: Cronbach’s α = .61; session 2: Cronbach’s α = .77; across both sessions: Cronbach’s α = .78).

Well-being and Longevity

Participants completed a set of well-being indicators and associated measures of emotion regulation tendencies.

Positive vs. negative affect

Participants were asked to recall ten situations (Kitayama, Park, Sevincer, Karasawa, & Uskul, 2009). Some of these episodes involved social relations (e.g., ‘having a positive interaction with friends’), some were related to study and work (e.g., ‘being overloaded with work’), and some others concerned daily hassles and bodily conditions of the self (e.g., ‘being caught in a traffic jam’). Participants were asked to remember the latest occasion when each of the 10 situations happened to them. They were asked to report the extent to which they experienced a series of emotions in these situations. The list of emotion terms contained 7 positive (e.g. feeling of closeness, pride, elated, happy) and 5 negative (e.g. ashamed, frustrated, angry, unhappy) emotions. Six-point scales that ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 6 = “very strongly” were used in rating emotional experience. To minimize possible age-related positivity effect in memory (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005) we followed the recommendations by Kahneman and colleagues (Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004) and performed our analyses on the episodes from the preceding two days2. We averaged the scores for positive (Cronbach's α = .88) vs. negative emotions (Cronbach's α = .68).

Relationship satisfaction

We asked participants to consider their personal network including people “who are important in your life right now.” Participants reported the initials of such people in three concentric circles, ranging from “people to whom you feel so close that it is difficult to imagine life without them” (inner-most circle) to “people who are close enough and important enough in your life that they should be placed in your personal network” (outer circle). Network members included relatives (44%, M = 12.74, SD = 8.71), non-kin friends (42%, M = 14.86, SD = 14.07) and acquaintances (14%, M = 5.11, SD = 6.20). Next, participants indicated initials of those network members, who “have given you advice and social support during the last month.” We counted the number of such individuals as an index of positive relations (M = 5.39, SD = 4.50). Finally, we asked them to indicate initials of those member who “have caused annoyances and troubles during the last month”, which we counted as an index of negative relations (M = 1.85, SD = 2.11). Following previous research (Fiori, Antonucci, & Akiyama, 2008), we obtained the index of relationship satisfaction by examining the relative proportion of distinctly positive vs. negative relationships. In order to normalize the skewed distribution, the resulting scores were log-transformed.

Rumination

Participants next completed the 5-item Brooding subscale of the Ruminative Response Scale, which examines an emotion regulation tendency to respond to distress by repeatedly reflecting on past negative experiences (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). For instance, one of the questions asked participants to indicate how often they think ‘What am I doing to deserve this?’ from 1 = “almost never” to 4 = “almost always.” In the present study this scale has showed acceptable reliability, which was comparable to previous research (Cronbach’s α = .69).

Life satisfaction

Participants further answered a life satisfaction question (a common technique in well-being research; Kahneman, Diener, & Schwarz, 1999): “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” on a 10 point scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 10 (“very much satisfied”). This measure was administered via a survey distributed a year after completion of the experimental sessions, resulting in a smaller sample size (N = 141).

Longevity

Finally, because subjective well-being is a strong predictor of longevity (Chida & Steptoe, 2008), we explored how wise reasoning relates to longevity five years after completion of the first session of our study by examining publicly available death records.

Emotional discourse

In an attempt to supplement the main well-being measures reported in this study with implicit measures that are less susceptible to demand effects, we explored emotional discourse patterns. We re-analyzed participants’ narratives about the social conflicts using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count program (LIWC; Pennebaker, Francis, & Booth, 2001). This program analyzes texts on a probabilistic basis by comparing files on a word-by-word basis to a dictionary of 2,290 words and word stems that are organized into several different language categories. The analysis computes the percentage of total words found in the text that belong to these language categories. We took the relative percentage of positive to negative affect words contained in the narratives as an index of positive vs. negative thought accessibility. We focused on this index, because previous research indicated that counting positive vs. negative words in verbal and written discourse about oneself and others is positively associated with greater self-report positive affect (Pennebaker, Mehl, & Niederhoffer, 2003), lower neuroticism and greater agreeableness (Pennebaker & King, 1999), and predicts longevity (Danner, Snowdon, & Friesen, 2001).

Covariate Measures: Speed of Processing, Cognitive Abilities and Personality

Given the novelty of our measure of wise reasoning, we also tested its relationships to cognitive abilities and personality traits. Participants completed two tests of processing speed (Hedden et al., 2002) and the digit span sub-test of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (rforward-backward = .49, p < .001). Speed of processing scores were significantly correlated (r = .69, p < .001) and thus were standardized and collapsed into a single index. Participants also completed comprehension and vocabulary subtests of WAIS (r = .52, p < .001).

The Big-Five personality dimensions were measured using the Ten Item Personality Measure, which has shown high convergent validity with other Big-Five personality measures in past research (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann Jr, 2003), and the highest convergence with the 60-item NEO-FFI in comparison to other short Big Five measures (Furnham, 2008). The two items per each dimension were significantly correlated (rextraversion = .53, p < .001; ragreeableness = .19, p < .05; rconscientiousness = .37, p < .001; rneuroticism = .48, p < .001; ropenness = .40, p < .001). Following an established procedure (Gosling, et al., 2003), we collapsed the pairs of scores into a single index for each of the five personality dimensions.

Control Variables: Perceived Health and Social Class

Perceived health was measured with a 3-item health questionnaire (e.g. "Compared to other people your own age, how would you rate your physical health?"; Hedden, et al., 2002; Cronbach's α = .78). Participants also provided demographic information including their age, education, family income, and their occupation. We coded participants’ occupations using the International Socioeconomic Index of Occupational Status (Ganzeboom & Treiman, 1996).

Results

Preliminary Analyses: Inter-item Correlations and Factor Extraction

Results from exploratory analyses are summarized in Table 3. All pair-wise correlations of wise reasoning dimensions were significant except for limits of knowledge being unrelated to change and conflict resolution (mean r = .25). Principal component analyses and a screeplot provided evidence for a single factor, which accounted for over 38 % of the variance. An alternative two-factor solution yielded highly correlated factors (r = .67), with the second factor explaining a comparable amount of variance as each of the six items by itself (17%). In the interest of parsimony and to enhance measurement reliability, we collapsed the scores into a single index3.

Table 3.

Factor Loadings for the 6 Dimensions, and Dimension Inter-correlations.

| Inter-correlations |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings |

2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

| 1. change | .56 | .23*** | .23*** | .26*** | .38*** | .03 |

| 2. compromise | .70 | - | .44*** | .35*** | .27*** | .14* |

| 3. flexibility | .76 | - | .35*** | .25*** | .43*** | |

| 4. perspective | .64 | - | .17** | .17** | ||

| 5. resolution | .55 | - | .03 | |||

| 6. limits of knowledge | .44 | - | ||||

Note.

p ≤ .001.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .05.

Relation to Cognitive Abilities and Personality

As shown in Table 4, speed of processing was negatively correlated with wise reasoning about intergroup conflicts (an artifact of differential age effects on processing speed and wise reasoning, rpartial = .05, ns), whereas verbal cognitive abilities were positively associated with wise reasoning. Specifically, WAIS-Comprehension was positively associated with wise reasoning about interpersonal scenarios, and WAIS-Vocabulary was positively associated with wise reasoning about both intergroup and interpersonal conflicts. Among the Big Five factors, only agreeableness was positively related to wise reasoning.

Table 4.

The Relationship between Wise Reasoning, Well-being, and Analytic Abilities and Personality

| Wise Reasoning |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Intergroup (session 1) |

Interpersonal (session 2) |

Total | |

| Relation to well-being | |||

| Life-satisfaction (n = 144) | .16* | .07 | 17* |

| Positive affect (n = 222) | .03 | −.04 | .01 |

| Negative affect (reverse-scored; n = 222) | .18** | .23** | .27*** |

| Relationship quality (log; n = 166) | .23** | .15* | .25*** |

| Depressive brooding (reverse-scored; n = 185) | .33*** | .18** | .33*** |

| Positive vs. negative words in speech (n = 221) | .16* | .16* | .19** |

| Relation to cognitive abilities and personality | |||

| Analytic abilities | |||

| Speed of processing | −.25*** | −.05 | −.25*** |

| WAIS Digitspan | −.01 | .02 | .01 |

| WAIS Comprehension | .03 | .22** | .08 |

| WAIS Vocabulary | .15* | .31*** | .25*** |

| Big Five personality dimensions | |||

| Neuroticism | −13 | −.11 | −.15 |

| Extraversion | −.06 | −.07 | −.06 |

| Openness | .05 | .01 | .06 |

| Agreeableness | .24* | .20† | .27** |

| Conscientiousness | .09 | .16 | .12 |

Note. Zero-order correlation coefficients. Personality measures were assessed via a mailed questionnaire 2 years upon completion of the laboratory sessions, leading to an attrition (n = 104).

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Relation to Well-being

Table 4 indicates a significant association between wise reasoning and a wide range of well-being indicators. Participants who scored high on wise reasoning reported less negative affect in daily life, better relationship quality, greater life satisfaction, less tendency to brood, and a more positive way of talking about social conflicts, but not more positive affect in daily life. This pattern of results was highly consistent across both intergroup and interpersonal scenarios.

In contrast to wise reasoning, cognitive abilities showed no systematic relationship to the well-being indicators. Faster speed of processing was negatively related to positive affect (r = −.13, p = .06) and relationship quality (r = −.15, p = .05), and positively related to brooding (r = .12, p = .10). Greater crystallized abilities were correlated with less positive affect (rWAIS-Comprehension = −.19, p = .006; rWAIS-Vocabulary = −.26, p = .001), and less negative affect (rWAIS-Vocabulary = −.14, p = .07). However, higher scores on the WAIS-Comprehension task were positively related to frequency of positive vs. negative words in the discourse (r = .13, p = .06). The remaining correlations between cognitive abilities and well-being indicators were negligible (|rs|< .09).

Replicating previous work, personality factors showed a number of significant correlations with well-being (Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). Neuroticism was related to less life-satisfaction (r = −.52, p < .001), less positive affect (r = −.25, p = .01), more negative affect (r = .22, p = .03), and more brooding (r = .51, p <.001). Agreeableness was related to more life-satisfaction (r = .23, p = .03), more positive affect (r = .23, p = .02), less negative affect (r = −.19, p = .05), greater relationship quality (r = .36, p = .001), less brooding (r = .25, p = .02), and more positive vs. negative words in discourse (r = .22, p = .02). Extraversion was related to lower life-satisfaction (r = −.22, p = .04), but also less negative affect (r = −.18, p = .07). Finally, conscientiousness was linked to more positive and less negative affect (r = .24, p = .02 and r = −.21, p = .03, respectively).

Wisdom and well-being: Control analyses with cognitive abilities, personality, and socio-demographic factors

We next ran a series of multivariate regression models, in which we simultaneously included wise reasoning and a set of covariates as predictors of well-being. Specifically, we tested how wise reasoning predicts well-being, when controlling for a set of crystallized cognitive abilities (WAIS comprehension and vocabulary tests), agreeableness, or length of elaboration (quantified as the number of words in the narrative). As Table 5 indicates, wise reasoning remained a significant predictor of the majority of well-being indicators when simultaneously controlling for verbal abilities, agreeableness and response length. There were two exceptions. First, and similar to analyses without covariates, wise reasoning did not predict more positive affect. Second, wise reasoning did not significantly predict more life satisfaction when controlling for agreeableness (β = .14, t = 1.51, p = .13). Moreover, structural equation analyses in which all well-being indicators were modeled as part of a latent well-being construct regressed on wise reasoning and covariates, indicated a significant overall effect of wise reasoning in each of the three models. In addition, Table 6 shows that including wise reasoning in the model with socio-economic factors and perceived health predicting well-being improves the fit of regression models for each well-being indicator except for positive affect, as indicated by the Model II R2 significance level.

Table 5.

Wisdom and Well-being: Control Analyses with Cognitive Abilities, and Personality

| Model | LS | POS | NEG | REL | BROOD | SPEECH | WB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Wise reasoning | .165 / 1.896† | .064 / .961 | .275 / 4.316*** | .251 / 3.138** | .343 / 4.891*** | .201 / 2.970** | .497 / 6.243*** |

| WAIS-Compr | −.057 / .599 | −.083 / 1.103 | .060 / .797 | .012 / .134 | .079 / .992 | .173 / 2.201* | .093 / .983 | |

| WAIS-Vocab | −.012 / .121 | −.218 / 2.748** | .023 / .279 | −.087 / .959 | −0.077 / .957 | −.123 / 1.279 | −.099 / .974 | |

| R2 | .031 / 1.014 | .076 / 2.027* | .081 / 2.331* | .070 / 1.576 | .124 / 2.476* | .065 / 1.749† | .240 / 3.195*** | |

| II | Wise reasoning | .138 / 1.509 | −.007 / .103 | .268 / 4.216*** | .183 / 2.229* | .309 / 4.264*** | .174 / 2.542* | .359 / 3.981*** |

| Agreeableness | .160 / 1.322 | .214 / 2.116* | .158 / 1.600 | .320 / 3.493*** | .183/ 1.749† | .150 / 1.420 | .433 / 3.683*** | |

| R2 | .044 / 1.138 | .046 / 1.056 | .097 / 2.346* | .136 / 2.352* | .129 / 2.585** | .052 / 1.482 | .406 / 3.648*** | |

| III | Wise reasoning | .166 / 1.743† | −.001 / .015 | .271 / 4.044*** | .214 / 2.493* | .355 / 4.993*** | .212 / 3.044** | .491 / 5.998*** |

| Response length | −.011 / .124 | .048 / .661 | .040 / .569 | .051 / .637 | −.065 / .928 | −.064 / .925 | −.030 / −.355 | |

| R2 | .028 / .853 | .002 / .328† | .075 / 2.161* | .048 / 1.396 | .130 / 2.421** | .049 / 1.471 | .232 / 3.125** | |

Note. Standardized beta coefficients and t-values. LS = life satisfaction; POS = positive affect; NEG = less negative affect; REL = relationship quality; BROOD = less rumination; SPEECH = positive vs. negative words when talking about social conflicts. Missing cases estimated with Mplus 6.1 full-maximum likelihood procedure. WB = latent well-being construct with contribution from each wellbeing indicator. Model fit indices (RMSEA): I = .06; II = .04; III = .04.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Table 6.

Model Comparison: Socio-demographic Factors vs. Socio-demographic Factors and Wise Reasoning

| Model | LS | POS | NEG | REL | BROOD | SPEECH | WB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Occupation | −065 / .680 | −221 / 3.018** | .039 / .503 | −103 / 1.194 | −009 / .113 | −070 / .893 | −061 / .623 |

| Edu (years) | .062 / .665 | −006 / .076 | .045 / .595 | .103 / 1.163 | .034 / .421 | .041 / .533 | .076 / .807 | |

| Income (log) | −002 / .023 | −089 / 1.318 | −050 / .735 | −090 / 1.179 | −141 / 1.990* | .122 / 1.787† | −133 / 1.541 | |

| Perceived health | .198 / 2.543** | .282 / 4.520*** | .191 / 2.887** | .160 / 2.145* | .285 / 4.259*** | .070 / 1.033 | .417 / 5.264*** | |

| ♂= ½/♀=−½ | .039 / .491 | .043 / .682 | .044 / .671 | −170 / 2.309* | .053 / .766 | −072 / 1.080 | .034 / .412 | |

| R2 | .043 / 1.384 | .116 / 2.822** | .052 / 1.783† | .072 / 1.846† | .108 / 2.527** | .027 / 1.227 | .198 / 2.934** | |

| V | Occupation | −084 / .887 | −225 / 3.052** | .007 / .089 | −124 / 1.462 | −047 / .606 | −093 / 1.189 | −111 / 1.216 |

| Edu (years) | .052 / .564 | −007 / .098 | .030 / .407 | .083 / .945 | .006 / .081 | .028 / .377 | .047 / .540 | |

| Income (log) | −002 / .029 | −089 / 1.324 | −048 / .729 | −086 / 1.156 | −142 / 2.110* | .120 / 1.801† | −131 / 1.637 | |

| Perceived health | .192 / 2.460* | .280 / 4.487*** | .178 / 2.755** | .144 / 1.944* | .267 / 4.111*** | .058 / .869 | .387 / 5.143*** | |

| ♂= ½/♀=−½ | .051 / .641 | .046 / .721 | .065 / 1.021 | −152 / 2.067* | .078 / 1.189 | −057 / .874 | .064 / .847 | |

| Wise reasoning | .152 / 1.716† | .029 / .452 | .269 / 4.272*** | .208 / 2.573** | .323 / 4.695*** | .191 / 2.834** | .454 / 5.984*** | |

| R2 | .063 / 1.687† | .118 / 2.835* | .112 / 2.915* | .108 / 2.358* | .197 / 3.782*** | .063 / 1.913† | .396 / 4.799*** | |

Note. Standardized beta coefficients and t-values. LS = life satisfaction; POS = positive affect; NEG = less negative affect; REL = relationship quality; BROOD = less rumination; SPEECH = positive vs. negative words when talking about social conflicts. Missing cases estimated with Mplus 6.1 full-maximum likelihood procedure. WB = latent well-being construct with contribution from each well-being indicator. Model fit indices (RMSEA): IV = .05; II = .04; V = .05.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Longevity

Because mortality is quite rare among younger adults, longevity analyses focused on participants above 45 years of age. The results were comparable when exploring the impact of wise reasoning on longevity on the full sample. The results of a probit model regression with wise reasoning and age as predictors, and longevity (1=”dead” vs. 0=“alive”; 13 out of 127) as the dependent variable showed a significant effect of age (B = .048, SE = .019, |t| = 2.58, p = .01), and a marginally significant effect of wisdom on longevity4 (B = −1.325, SE = .782, |t| = 1.70, p = .09). The effect of wise reasoning on longevity remained significant in analyses with such covariates as socio-demographic factors (gender, education, occupational status, income), and perceived health (B = −1.389, SE = .806, |t| = 1.72, p = .09), or verbal cognitive abilities (B = −1.325, SE = .782, |t| = 1.70, p = .09).

Age, Wisdom, and Wellbeing

We subsequently examined whether wise reasoning mediates the relationship between age and well-being by performing a structural equation analysis with well-being indices as indicators of a latent well-being construct. Each well-being indicator showed significant contribution to the latent well-being construct, and the model showed an acceptable fit, χ2 (19) = 27.13, RMSEA = .04, CFI = 96). Indicators such as life-satisfaction (β = .549, t = 6.41, p < .001), negative affect (reverse-coded; β = .516, t = 7.16, p < .001), relationship quality (β = .345, t = 4.00, p < .001) and brooding (reverse-coded; β = .718, t = 10.37, p < .001) showed substantial contribution, whereas the contribution of positive affect (β = .184, t = 2.24, p = .025) and positive speech (β = .238, t = 2.83, p = .005) was comparably smaller.

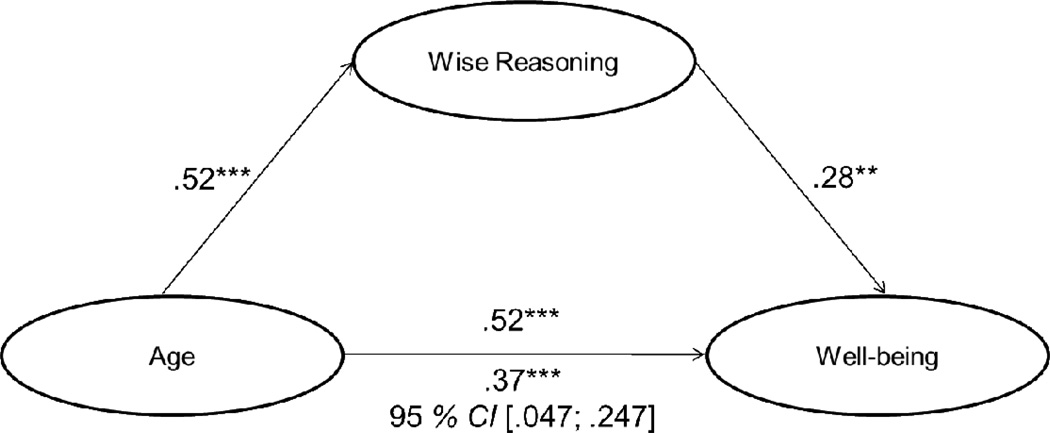

As Figure 1 illustrates, age was positively related to wise reasoning and well-being, and the effect of wise reasoning on well-being was significant when controlling for age. Moreover, the indirect effect of age on well-being via wise reasoning was significant (see Figure 1 for 95% Confidence Intervals from a non-parametric bootstrap test with 2000 random replacements – the technique of choice for assessing indirect effect in smaller samples; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). Follow-up analyses indicated that the indirect effect was significant for middle-aged (at Mage; Sobel Z = 1.90, p = .057; 90 % CI [.001; .004]) and older adults (1 SD above Mage ; Sobel Z = 2.43, p = .015, 90 % CI [.001; .004]), but not for younger adults (1 SD below Mage; Sobel Z = 1.24, ns., 90 % CI [0; .003]), suggesting that the indirect effect of age on well-being via wise reasoning was moderated by age (Preacher, et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Wise reasoning mediating the effect of age on well-being in a structural equation model. Standardized coefficients are shown. The value under the age →well-being path reveals the relationship between age and well-being, after controlling for wise reasoning. Statistical significance is indicated by superscripts (*p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .005). The values in the square brackets correspond to the 95% confidence interval from a bootstrap test performed to assess the significance of the indirect effect. The mediation is significant if the confidence interval does not include zero.

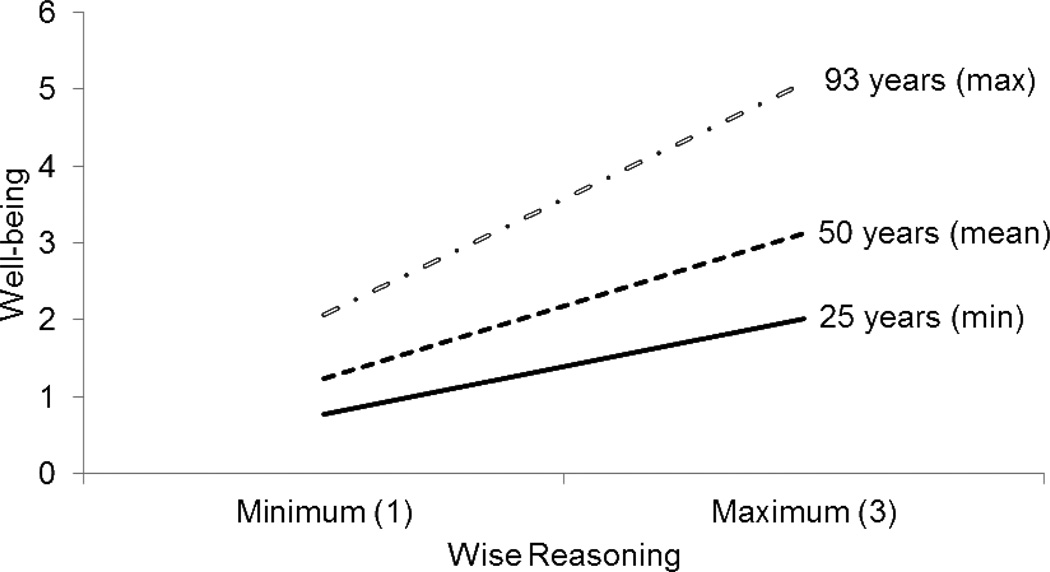

Further analyses with wise reasoning, age and their interactions predicting well-being showed a significant effect of wise reasoning (β = .220, t = 2.19, p =.028), age (β = .367, t = 4.15, p <.001), and a marginal interaction (β = .158, t = 1.77, p =.077). Comparable analyses with gender and wise reasoning predicting well-being showed a significant effect of wise reasoning on well-being (β = .483, t = 6.28, p < .001), but no significant effects of gender (β = .055, t = .69, ns) nor was there a gender X wise reasoning interaction (β = .007, t = .08, ns). Subsequent simple slope analysis (Aiken, Reno, & West, 1996) are illustrated in Figure 2. The relationship between wise reasoning and well-being was marginally significant among the middle-aged (at Mage; B = .297, SE = .159, t = 1.86, p = .06), and significant among the older adults (1 SD above Mage; B = .518, SE = .208, t = 2.49, p < .01), but not significant among the younger adults (1 SD below Mage; B = .076, SE = .218, t < 1, ns.).

Figure 2.

The association between wise reasoning and well-being as moderated by participants’ age in a multivariate regression analysis. Simple slopes for the minimum, mean, and maximum ages in the sample are shown.

Summary

Consistent with prior research, cognitive abilities such as crystallized intelligence, processing speed and working memory showed no systematic relationship to well-being. In contrast, the ability to reason wisely about social conflicts was associated with greater global life satisfaction, greater satisfaction with social relationships, less negative affect in daily life, a lower propensity to brood, relatively positive discussion social conflicts, and greater longevity. This positive association between wise reasoning and well-being was consistent when looking separately at wise reasoning about intergroup and interpersonal conflicts, and when controlling for crystallized cognitive abilities, or individual differences in personality. Importantly, wise reasoning was not related to greater positive affect in daily life. The latter finding suggests that people who reason wisely are more content without being chronically more positive5.

Moreover, wise reasoning explained a greater amount of variance in individual well-being than did gender or various socio-economic indicators. We also observed two age-related patterns. First, the effect of age on well-being was partially mediated by wise reasoning. Second, the link between wise reasoning and well-being was stronger among older adults, and absent among younger adults.

Discussion

Psychologists have long sought to identify strategies that are reliably associated with greater well-being (Seligman, 2002). The observation that wise reasoning improves into old age (Grossmann, et al., 2010; Worthy, et al., 2011) in conjunction with experimental work on the malleability of wise reasoning (Kross & Grossmann, 2012) suggests that it may be possible to train people to reason wisely. Our findings further suggest that wise reasoning is a potential psychological mechanism which may explain age-related differences in well-being. This finding dovetails with work by Carstensen and colleagues demonstrating that as people age they shift their priorities towards interpersonal issues and develop greater emotional competence (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). Extending this work, the present research demonstrated that older adults show greater ability to reason wisely about social conflicts than younger adults, and that among middle-aged and older adults such reasoning is positively linked to socio-emotional benefits.

In interpreting the results of our research, one important consideration deals with the directionality of the relationship between wise reasoning and well-being, as well as between wise reasoning and longevity. In the present paper we suggested that wiser reasoning about social conflicts leads to greater well-being and not vice versa. A reversal would suggest that positive affect facilitates a desire to explore the world (e.g. Fredrickson, 1998), which, in turn, might lead to more experience and stimulate the development of wise reasoning. But positive affect was not related to well-being, thus it seems unlikely that wisdom is the product of chronic positive affect. At the same time, it is plausible that some core emotional and social intelligence may contribute both towards greater wise reasoning and good mental health. Further, well-being has been linked to greater longevity on its own right (Carstensen et al., 2011), suggesting some common underlying mechanism for wise reasoning and well-being has an effect on longevity. Therefore, additional longitudinal research with the simultaneous assessment of wise reasoning, emotion regulation strategies (Gross & John, 2003) and social intelligence (Cantor & Kilhlstrom, 1987) would be useful in order to gain deeper insight into the directionality of the relationship between wise reasoning and well-being and the processes which may underlie this relationship.

Another important question deals with the divergence between the present findings and those of previous research that has explored the relationship between wisdom-related knowledge and well-being (Kunzmann & Baltes, 2003; Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). First of all, in contrast to the previous studies, we provided meaningful contexts, which would help older participants reason in a wise way. Also, due to the lack of contextual information, participants in their studies should have relied on their own knowledge about specific life events (e.g., suicide attempt). We believe that such focus on specific factual knowledge may be problematic. A large body of research in cognitive psychology has demonstrated that knowledge acquired through experiences in one situation often fails to transfer to another (Singley & Anderson, 1989). Therefore, when measuring knowledge about specific life events, it may be important to sample from a heterogeneous set of life domains to make accurate estimations about one’s declarative knowledge about such events. Conflating wise reasoning with specific knowledge about life dilemmas may also be problematic for some other reasons. It is plausible that wiser people may show a lower likelihood of encountering challenging life dilemma, and therefore have less specific knowledge about them. This may be because wiser individuals are more likely to recognize and potentially preempt some of these dramatic life events. Further, scoring individuals with great specific knowledge about life tragedies as wiser could introduce confounds with regard to the link between wisdom and individual well-being: people who have greater knowledge about very difficult situations presumably learned about them from personal experiences, thus their psychological well-being might be lower. An important avenue for future research would be to test the extent to which development of wisdom-related reasoning depends on personal or vicarious life experiences, and if such experiences strengthen or weaken the link between wise reasoning and well-being.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that lay beliefs about the relationship between reasoning abilities and well-being are correct, with one caveat. Whereas wise reasoning about social conflicts contributes to well-being, abstract cognitive abilities (as measured by intelligence tests) do not. On the practical side, the present work suggests that despite the cognitive declines often associated with older age, the increasing number of older adults may be of great value for the social and emotional well-being of our future communities.

Table 2.

Example Responses for the Immigration Story, indicating Low and High Wise Reasoning.

| low | high |

|---|---|

|

Search for a Compromise | |

| I’m sure that each, each culture will keep their original customs. It’s not likely that someone that’s lived a certain way is going to change just because they moved to a new area. (…) People are pretty true to their nature and they’re not really big on change so I’m sure that it won’t be an easy thing for them to change their culture. | They might want to let them continue with their ways and maybe at the same time maybe try to do some kind of promotion to encourage them to better assimilate into the culture though, not throw away their own culture, but to try to make the country more unified, maybe bring customs together that might be similar for both cultures, in order to unify the country. |

|

Recognizing Multiple Ways How the Conflict Might Unfold | |

| Most likely there is going to be very similar things as going on in the United States […] the economic drivers are going to want to keep the immigration going and more traditionalists are going to want to stem it and make laws like only speaking Tajik, instead of both. […] It seems like that’s happened throughout the world history when you get a large number of immigration coming in. | It’s hard to predict in a short period of time if the Kyrgyz will be assimilated with the Tajiks or whether there will begin to be unrest and civil disunity because of this immigration.[…] I don’t think it will necessary happen either way. You have several possibilities. Either taking historically into account what has happened: One you will have assimilation and happiness or two you will have constant bickering and at least social disunity and social warfare. |

|

Considering Perspectives of People Involved in the Conflict | |

| I think eventually it’ll be like what’s happening in the U.S. is that all the different cultures will merge. If it’s really productive for the country I think the cultures will merge and there’ll be more peace within them. […] I think that they’ll let them come in, because they need the labor force. […] There’s going to be some conflict of social interests and their cultures… There’s going to be a little bit of culture difference. It sounds like that’s the main issue here, it’s just the culture. I think usually that ends up working out. | I think there’ll be friction between those two ideas. People do assimilate eventually but it often takes a couple generations to do that. (…) There’ll be influences both ways but people who are in particular countries that receive immigrants, they always see it from their point of view, namely that these immigrants are changing the country. They don’t necessarily see it from the other point of view. Also, immigrants might be upset because their children are not the way they would be if they were back in their homeland. |

Note. Some examples adapted from Grossmann et al., 2010.

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this paper was completed as part of Igor Grossmann’s dissertation research. It supported by the International Max Plank Research LIFE Fellowship, and the Rackham Pre-doctoral Dissertation Fellowship awarded to Igor Grossmann, and the NIA grant 5RO129509-02 awarded to Richard E. Nisbett and Shinobu Kitayama. We thank Robert J. Sternberg and Jacqui Smith for thoughtful comments on the previous version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This was particularly true in analyses with age as a covariate. Zero-order correlations in this study showed a negative relationship between wise reasoning and both forms of affect (positive or negative).

Participants reported at least one positive and one negative episode from the last two days. The main results look very similar when examining all episodes, e.g. wise reasoning was not related to positive affect (r = −.02), but wise reasoning was significantly negatively related to negative affect (r = −.16, p =.02).

In session 1 (intergroup conflicts) we explored wise reasoning about fictional scenarios, which had similar narrative structure. We attempted to increase the external validity in session 2 (interpersonal conflicts) by selecting scenarios from the real newspaper column. The greater diversity likely resulted in somewhat lower internal reliability of wisdom scores in session 2 (Cronbach’s α = .50) than in session 1 (Cronbach’s α = .71). We attempted to increase measurement reliability by performing the main analyses on the composite index across intergroup and interpersonal scenarios (Cronbach’s α on six wisdom dimensions across both sessions = .71). Results were comparable across both types of scenarios (see Table 4).

The association between wise reasoning and longevity/mortality was further moderated by participants’ age (B = .186, SE = .065, |t| = 2.87, p = .004). Simple slopes analyses (Aiken, et al., 1996) indicated that middle-aged participants who scored low (10th quantile) on wise reasoning showed similarly high mortality probability as their older counterparts (B = .022, SE = .037, |t| < 1, ns.). However, middle-aged participants who scored above average (50th quantile) on wise reasoning showed significantly lower mortality probability than their older counterparts (B = 1.208, SE = .036, |t| = 3.33, p < .001). In addition, wise reasoning did not significantly contribute towards greater longevity among participants above 67 years of age (|B|< 2.299, SE = 1.644, |t| = 1.40, p = .16). Note, however, that the death numbers in the present study were fairly small, thus interaction results have to be interpreted with caution.

The null relationship between wise reasoning and positive affect dovetails with some developmental work, suggesting that the greater well-being in older age is mainly accounted by steep declines in negative affect and only a modest increase in positive affect (Stone, Schwartz, Broderick, & Deaton, 2010).

References

- Aiken LS, Reno RR, West SG. Multiple regression : testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, California: SAGE; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Smith J. The fascination of wisdom: Its nature, ontogeny, and function. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(1):56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Staudinger UM. Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. The American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):122–136. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basseches M. Dialectical schemata: A framework for the empirical study of the development of dialectical thinking. Human Development. 1980;23:400–421. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Converse PE, Rogers WL. The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York, NY: Russel Sage Foundation; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor N, Kilhlstrom J. Social Intelligence. New York: Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA. At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(3):117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(4):644–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(1):21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61(1):383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danner DD, Snowdon DA, Friesen WV. Positive emotions in early life and longevity: findings from the nun study. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2001;80(5):804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Fujita F. Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68(5):926–935. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:403–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. Profiles of social relations among older adults: a cross-cultural approach. Ageing & Society. 2008;28:29. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:300–319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A. Relationship among four Big Five measures of different length. Psychological Reports. 2008;102(1):312–316. doi: 10.2466/pr0.102.1.312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom HBG, Treiman DJ. Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations. Social Science Research. 1996;25(3):201–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB., Jr A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality. 2003;37(6):504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, Karasawa M, Izumi S, Na J, Varnum MEW, Kitayama S, Nisbett RE. Aging and wisdom: Culture matters. Psychological Science. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446025. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, Na J, Varnum ME, Park DC, Kitayama S, Nisbett RE. Reasoning about social conflicts improves into old age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(16):7246–7250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001715107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Park DC, Nisbett RE, Ji L, Jing Q, Jiao S. Cultural variation in verbal versus spatial neuropsychological function across the lifespan. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:65–73. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Blanchard-Fields F. Social Cognition and Aging. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone AA. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science. 2004;306(5702):1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park H, Sevincer AT, Karasawa M, Uskul AK. A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(2):236–255. doi: 10.1037/a0015999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer D. Post-formal operations? A need for further conceptualization. Human Development. 1983;26:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D. Wisdom as a classical source of human strength: Conceptualization and empirical inquiry. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Grossmann I. Boosting wisdom: Distance from the self enhances wise reasoning, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012;141(1):43–48. doi: 10.1037/a0024158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U, Baltes PB. Wisdom-related knowledge: Affective, motivational, and interpersonal correlates. Personality & social psychology bulletin. 2003;29(9):1104. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonius Marcus., Emperor of Rome . Theories. In: Edwards T, editor. A Dictionary of Thoughts: Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors, Both Ancient and Modern. New York: Cassell Publishing Company; 1891. p. 644. [Google Scholar]

- Mickler C, Staudinger UM. Personal wisdom: Validation and age-related differences of a performance measure. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(4):787–799. doi: 10.1037/a0013928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(5):1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone J. An essay on wisdom: Toward organismic processes that make it possible. In: Sternberg RJ, editor. Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 244–278. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME, Booth RJ. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC): LIWC. Vol. 2001. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, King LA. Linguistic styles: Language use as an individual difference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(6):1296. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54(1):547–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J. What do we need to know about wisdom? Management Decision. 2006;44(9):1246–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J, Slack F. Conceptions of wisdom. Journal of Information Science. 2009;35(1):110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. What and When of Cognitive Aging. Current directions in psychological science. 2004;13(4):140–144. doi: 10.1177/0963721414535212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Authentic Happiness:Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: The Free Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman L. Is ignorance bliss? A reconsideration of the folk wisdom. Human Relations. 1981;34(11):965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Singley MK, Anderson JR. The transfer of cognitive skill. Cambrdige, Massachusets: Harvard University press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE. What intelligence tests miss : the psychology of rational thought. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM, Glück J. Psychological wisdom research. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):215–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. A balance theory of wisdom. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2(4):347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. The theory of successful intelligence. Review of General Psychology. 1999;3:292–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. Words to the wise about wisdom? Human Development. 2004;47(5):286. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ. Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg RJ, Jordan J. A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Deaton A. A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(22):9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watten RG, Syversen JL, Myhrer T. Quality of life, intelligence and mood. Social Indicators Research. 1995;36(3):287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Wirthwein L, Rost DH. Giftedness and subjective well-being: A study with adults. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21(2):182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Worthy DA, Gorlick MA, Pacheco JL, Schnyer DM, Maddox WT. With Age Comes Wisdom. Psychological science. 2011;22(11):1375–1380. doi: 10.1177/0956797611420301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]