Abstract

Presently, radiation-attenuated Plasmodia sporozoites (γ-spz) is the only vaccine that induces sterile and lasting protection in malaria-naïve humans and laboratory rodents. However, γ-spz are not without risks. For example, the heterogeneity of the γ-spz could explain occasional break-through infections. To avoid this possibility, we have constructed a double knockout P. berghei parasite by removing two genes, UIS3 and UIS4, upregulated in infective sporozoites. In this study we evaluated the double-knockout, Pbuis3(−)/4(−) parasites for protective efficacy and the contribution of CD8+ T cells to protection. Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induced sterile and protracted protection in C57BL/6 mice. Protection was linked to CD8+ T cells as mice deficient in β2m were not protected. Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune CD8+ T cells consisted of effector/memory phenotypes and produced IFN-γ On the basis of these observations we propose that the development of genetically-attenuated P. falciparum parasites is warranted for tests in clinical trials as a pre-erythrocytic stage vaccine candidate.

Keywords: malaria, liver-stages, genetically-attenuated Plasmodia, memory CD8 T cells, protection

Introduction

Malaria claims millions of lives annually [1] and a malaria vaccine is urgently needed [2]. Although pre-erythrocytic stage subunit vaccines are promising, it is unclear whether they will engage the required components of the innate and adaptive immune responses to confer long-term protection. Following the report [3] that immunization with x-irradiated Plasmodium gallinaceum sporozoites confers protective immunity, the use of radiation-attenuated P. falciparum sporozoites (Pf γ-spz),a non-replicating, live parasites as an effective vaccine has been demonstrated in humans [4].

Presently, Pf γ-spz are the only vaccine inducing lasting and sterile protection in malaria-naïve subjects of diverse HLA backgrounds [5]. The use of radiation for sporozoite attenuation is, however, not without risk as it yields heterogeneously attenuated sporozoites. This process is also radiation dose-sensitive [6] and under-irradiated sporozoites remain infectious, while over-irradiated sporozoites are not sufficiently immunogenic to prevent infection [6, 7]. These problems prompted a search for other forms of attenuation that would render the parasite a more reliable vaccine.

Recently, we described the development of two genetically-attenuated P. berghei parasites, each with a targeted disruption of a single but different gene up-regulated in infective sporozoites and thus designated UIS3 [8] and UIS4 [9]. Both genes are essential for the development of liver-stage parasites. The protein encoded by the UIS4 gene localizes to the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) membrane [9]. PV localization was also recently shown for UIS3 [10]. UIS3 interacts with liver-fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) within hepatocytes and L-FABP expression levels directly correlate with liver stage growth [10]. Immunizations of C57BL/6 mice with either P.berghei {Pbuis3(−)} or Pbuis4( −) mutants confer protection against WT homologous challenge [8, 9].

A single gene knock-out parasite might not be suitable as a vaccine for humans as it could give rise to break-through infections. To safeguard against this possibility, we developed a double knock-out parasite, Pbuis3(−)/4(−)parasite in which both genes, UIS3 and UIS4, were deleted (manuscript in preparation, K. Matuschewski et al). The question remained, however, whether the double knock-out parasite is sufficiently immunogenic to induce protection. The mechanism of induction and maintenance of protection by the genetically-attenuated Plasmodia is unexplored, although it likely stems from the inability of arrested early liver-stage parasites to develop into mature liver-stage schizonts [8, 9]. We and others have shown that treatment with primaquine, a drug that disrupts liver-stage parasites and hence prevents the expression of protein Ags, results in the loss of γ-spz-induced long-term protection in rodents [11, 12] and a shorter time to re-infection in humans [13]. It is believed, therefore, that proteins from the arrested liver-stage parasites provide the key Ags required for the induction of effector CD8+ T cells and possibly for the maintenance of protection by memory CD8+ T cells [14].

The evidence that CD8+ T cells are the sine qua non effectors against liver-stage infection comes from the observations that adoptively transferred γ-spz-immune CD8+ T cells confer protection [15] and that γ-spz do not protect mice deficient in CD8+ T cells either as a result of in vivo depletion of these cells [16] or β2m [17] or MHC class I (KbDb) disruption [14]. In the Pfγ-spz model, both CD8+ CTL [18] and IFN-γ responses are critical for protection against liver-stage parasites and most of the current focus has shifted towards cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells. We have demonstrated that Pbγ-spz-induced long-lasting, protective immunity is MHC class I-dependent [17] and is accompanied by the presence of CD8+ effector memory (TEM) and central memory (TCM) cells in the liver [12]. While CD8+ TEM cells produce IFN-γ in response to infectious challenge, CD8+ TCM cells undergo homeostatic proliferation (U. Krzych, manuscript in preparation) and thereby form the reservoir of memory T cells [14].

In this study we tested the protective efficacy of Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz against P.berghei sporozoite challenge. We also asked whether protection induced by Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz involves MHC class I molecules and CD8+ T cells. The results demonstrate for the first time that similar to Pbγ-spz, Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induced intrahepatic CD8+ TEM and TCM cells and that Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induced IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells that were recalled even after a re-challenge at 6 months. This and other studies [8, 9, 19] showing that genetically-attenuated Plasmodia sporozoites are efficient at inducing and maintaining protective immunity support our efforts to develop genetically-attenuated P. falciparum sporozoites as a pre-erythrocytic-stage vaccine for human use.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 and β2m−/− (6 – 8 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were housed at WRAIR and SBRI animal facilities and handled according to institutional guidelines. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of both institutes and were performed in facilities accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

Generation and propagation of sporozoites

We generated a Pbuis3(−)/4(−)double knock-out strain by targeting the UIS4 locus in the uis3(−) mutant parasite line [8] with a second selectable marker (hDHFR). Details of the double gene disruption will be published elsewhere (Matuschewski et al., manuscript in preparation). The phenotypic analysis of the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) parasite revealed no impairment of blood-stage development, sporogeny, salivary gland invasion or hepatocyte invasion. Liver-stage development was completely arrested as shown previously [8, 9].

For P. berghei WT or Pbuis3(−)/4(−) sporozoite production, Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes were fed on gametocyte-infected mice. Sporozoites were dissected [12] from the salivary glands of mosquitoes 16–21 days after the blood meal and used either immediately or after attenuation with γ-radiation (15,000 rad) (Cesium-137 source Mark 1 series or Cobalt-60 Model 109; JL Shepard & Associates, San Fernando, CA).

Immunizations

Mice were primed (i.v.) with 75K of either Pbγ-spz [12] or Pbuis3(−)/4(−)spz followed by two boost immunizations of 20K homologous sporozoites one week apart and were challenged with 10K infectious sporozoites one week later. In some experiments mice were re-challenged 6 months after challenge. In addition, various regimens of immunization and challenge were performed with Pbuis3(−)/4(−)spz. These included 3 immunizations of 10K Pbuis3(−)/4(−)spz given one week apart followed by a challenge of 10K infectious sporozoites on day7 or day118 after the last immunization.

Thin blood smears were prepared from individual mice starting on day 2 after challenge and parasitemia was determined microscopically using Giemsa stain. Mice were considered protected if parasites were not detected in 40 fields by day 14 after challenge.

Cell preparation

At various time points after immunization, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Livers were perfused with 10ml PBS, removed and pressed through a 70µM nylon cell strainer (BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and the cell suspension was processed as previously described [12]. Briefly, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 35% Percoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotec, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged at 2,000rpm for 20 min. Erythrocytes were lysed with lysis buffer (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and the remaining hepatic mononuclear cells (HMC) were resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium. Spleens were removed aseptically and a single cell suspensions prepared as described above. For isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), venous blood was collected into microtone tubes containing K2EDTA (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Erythrocytes were lysed and the remaining PBMC were washed in PBS and resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium.

Flow cytometry

Four-color staining of HMC, spleen cells or PBMC was performed using a combination of the following mAb: FITC-anti-CD45RB (16A), PE-anti-CD44 (IM7), PerCP-anti-CD8a (Ly-2), and APC-anti-CD44 (IM7), (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Briefly, 2–10 × 105 cells were resuspended in cold assay buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA (Sigma) and 0.01% sodium azide) and incubated with anti-FcR 24G2 (BD Biosciences) and 0.5 µg of the relevant mAb at 4°C for 30 min. Cells were washed and resuspended in cold assay buffer. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was performed using CELLQUEST (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

IFN-γ secretion assay

IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells were detected as described previously [12] using the secretion assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). Briefly, 1×106 cells were resuspended in 90µl cold assay buffer (PBS with 2mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA) containing 10µl of mouse IFN-γ and incubated on ice for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in 10 ml RPMI and were incubated at 37°C/5%CO2 for 45 min. under continuous shaking. After washing, the cells were resuspended in 90µl cold buffer containing 10µl PE-labeled IFN-γ detection reagent, 1µl anti-CD3 FITC and 1µl anti-CD8 APC and incubated on ice for 10 min. After washing, the cells were resuspended in 500µl of cold buffer. 10µl 7-AAD (25µg/ml) was added to the cell suspension and the sample immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Abs determinations

Sera from Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune WT and β2m−/− mice were tested for CS protein-specific Abs by ELISA. Briefly, two-fold serial dilutions of serum were dispensed into duplicate wells, previously coated with P. berghei GST-CS protein (provided by Dr. E. Angov, WRAIR). The plates were incubated at 22°C for 1hr. Following washes, 100µl of anti-mouse IgG AP conjugate (1µg/ml) was added and incubated at 22°C for 1hr. Following washes, 100µl of alkaline phosphate was added and incubated at 22°C for 1hr. Reaction was stopped with 10% SDS/H20 and the plates read on an ELISA plate reader (SPECTRAmax M2, Molecular Devices) using SoftmaxPro program at 450nm.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the means ± SD, and the differences among groups were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test using the Graphpad Prism software. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Immunization with Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz confers sterile protection

P. berghei parasites deficient in a single gene induce protection in mice [8, 9, 19]. However, single knock-out parasites may not be sufficiently attenuated and may compensate for loss of a single gene, resulting in an occasional break-through infections [9, 19]. To preclude this possibility, we constructed a novel, double knock-out Pbuis3(−)/4(−) strain and tested its ability to confer sterile protection against homologous WT sporozoite challenge in C57BL/6 mice. After weekly immunizations with 75K, 20K, 20K Pbγ-spz or Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz, mice were challenged one week later with 10K sporozoites. In some cases, mice were re-challenged 6 months after the primary challenge. Whereas naïve mice became parasitemic within 5 – 7 days after challenge, both Pbγ-spz- and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune mice were fully protected against primary and secondary (d 180) challenges (Table 1). A further investigation showed that 3 immunizations with 10K Pbuis3(−)/4−) spz also conferred full protection at challenge 118 days later (Table 1).

Table 1.

Protection of C57BL/6 Pbuis3(−)/4(−)spz-immunized mice against challenge with WT P. berghei sporozoites

| Priming* (Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz) |

Boosts* (Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz) |

Challenge dose (time point)† |

Number protected/ number challenged†† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75,000 | 20,000 (d 7)/20,000 (d 14) | 10,000 (d 7) (d 180) | 27/27(d 7); 6/6 (d 180) |

| 10,000 | 10,000 (d 14)/10,000 (d 28) | 10,000 (d 7) | 14/14 |

| 10,000 | 10,000 (d 14)/10,000 (d 28) | 10,000 (d 118) | 14/14 |

Data are presented as numbers of sporozoites used for priming and first/second boost immunizations. Day of boost is indicated in parentheses.

Mice were challenged with infectious P. berghei WT sporozoites. Time points in parentheses indicate the day of challenge after the final boost.

Data represent results from representative experiments; however, in total more than 100 mice were immunized with different doses of Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz and remained protected against challenge with infectious P. berghei sporozoites.

An age-matched naïve control group was included in each experiment and these mice all became blood stage patent at day 5–7 after challenge (not shown).

These data show for the first time that multiple immunizations with double knock-out Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz confer sterile and long-lasting protection against P. berghei liver-stage infection. Collectively, more than 100 mice remained solidly (100%) protected. experiments are in progress to assess the duration of protective immunity beyond the initial 6-month period.

Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induce hepatic CD8+TEM cells

Pbγ-spz enter hepatocytes where they undergo aborted development into liver-stage parasites that induce sterile immunity characterized by the presence of activated/memory hepatic CD8+ T cells. Because the knock-out parasites also colonize hepatocytes [8, 9], we asked whether Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced protective immunity against P. berghei liver-stage infection is also associated with the presence of activated/memory hepatic CD8+ T cells.

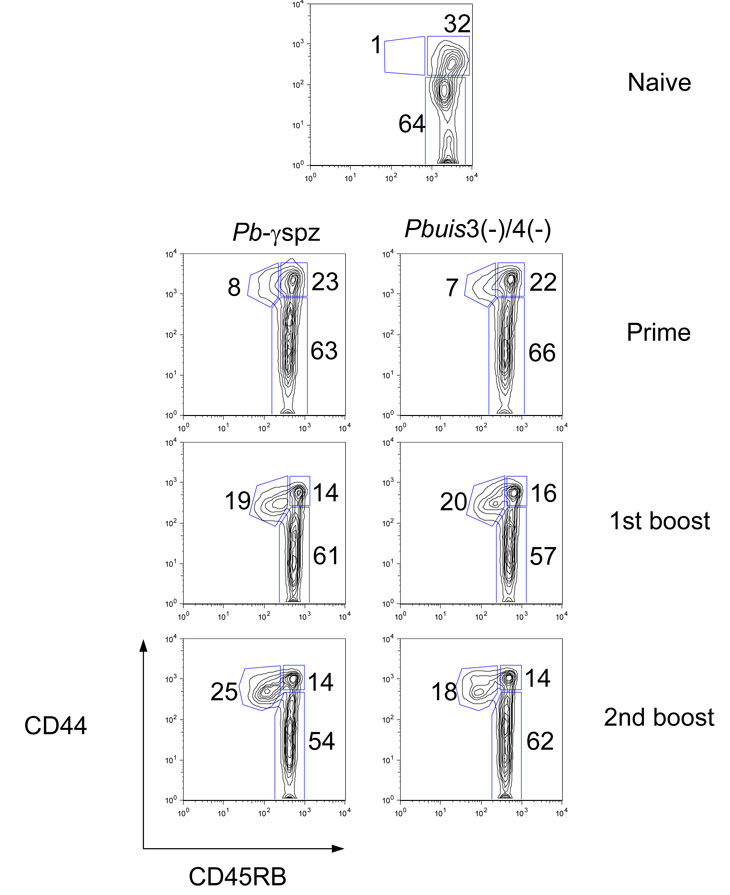

Hepatic and splenic CD8+ T cells isolated from Pbγ-spz- and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune mice were analyzed for the expression of the activation-related surface markers, CD44 and CD45RB, at different time points after priming and boost immunizations. Consistent with our previous observations with Pbγ-spz [12], Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced hepatic CD8+ T cells consisted of two distinct populations: CD8+ TCM cells (CD44hiCD45RBhi) and CD8+ TEM cells (CD44hiCD45RBlo) (Fig. 1). Naïve liver CD8 T cells contained a negligible percentage and number of CD8+ TEM cells, but ~30% already exhibited a TCM cell phenotype. After priming, the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced CD8+ TEM cells represented 10% ± 2 % of the hepatic CD8+ T cells and after the last boost immunization they increased to 28% ± 5% (Fig. 1), while CD8+ TCM cells concomitantly decreased from 25% ± 2% after priming to 17% ± 2% after boost immunization. The percentage of each CD8+ T cell subset at each time point examined was remarkably similar between the Pbγ-spz- and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune mice (Fig. 1). As previously reported for the Pbγ-spz [12, 20], only a small percentage (< 10%) of CD8+ TEM cells was found in the spleens of Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune mice (data not shown), thus confirming the enrichment of CD8+ TEM cells in the liver, a non-lymphoid organ, which is the site of liver-stage malaria infection.

Fig. 1. Pbγ-spz and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induce similar populations of phenotypically distinct subsets of CD8+ T cells.

(A) Hepatic mononuclear cells (HMC) were isolated from livers of 3 individual naïve or 3 immune mice 6 days after the indicated immunization and analyzed by flow cytometry. Lymphocytes labeled with anti-CD8 mAbs were gated on a forward-side scatter plot, and gates were applied to identify CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cell subsets were revealed using anti-CD45RB and anti-CD44 mAbs and percentages of subsets are shown as a dot plot from a representative mouse. The experiments were performed 3 times, with 3 mice/group and cells from individual mice were assayed. The data in the text are shown as the mean ± SD of responses observed in 9 individual mice.

Protracted protection induced by Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz is associated with the persistence of hepatic CD8+ TEM cells

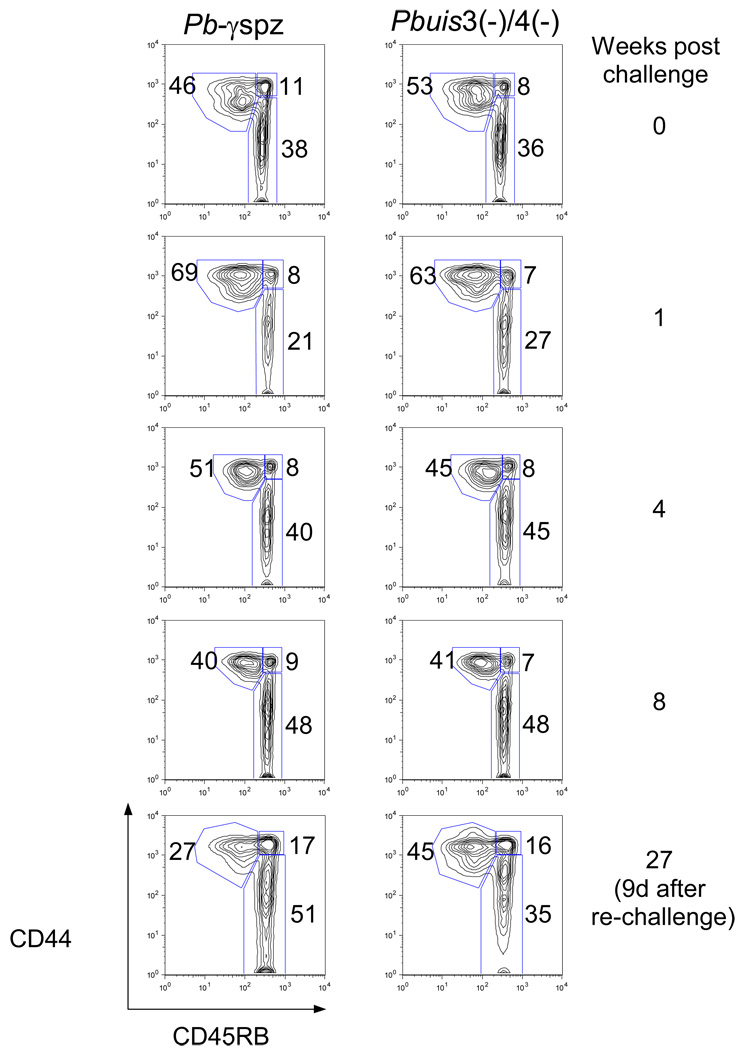

We asked if similar to Pbγ-spz-induced immunity [12] the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced hepatic CD8+TEM cells are maintained during protracted protection. In a longitudinal study we measured the levels of CD8+ TEM and TCM cells at the indicated time points after the challenge and re-challenge (Fig. 2A). One week after challenge, the accumulation of CD8+ TEM cells peaked (~60%) in both groups of mice, owing to either recruitment from the CD8+ TCM cells, or influx of extrahepatic cells into the liver, or both. The hepatic CD8+ TEM cells in both groups declined after the first week, presumably due to attrition as observed during infections [21]. At 8 weeks after challenge, CD8+ TEM cells remained at ~40% of in both groups (Fig. 2A). To examine the recall of memory responses, mice were re-challenged at 6 months, and CD8+ T cells were analyzed for subset distribution. In the Pbγ-spz-protected mice, 25% ± 6% of the hepatic CD8+ T cells were CD8+ TEM cells, while in Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-protected mice the CD8+ TEM cells represented 42% ± 5% of the total liver CD8+ T cells. The differences, however, were not statistically significant.

Fig. 2. CD8+ TEM cells are maintained after challenge and re-challenge of Pbγ-spz and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized mice.

(A) HMC were isolated from livers of individual mice at the indicated time points after immunization and challenge and analyzed as described in Fig. 1. The percentages of CD8+ T cell subsets are shown as a dot plot from a representative mouse. The experiments were performed 3 times, with 3 mice/group and cells from individual mice were assayed. The data in the text are shown as the mean ± SD of responses observed in 9 individual mice. (B) Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood of naïve mice or immune mice 6 days after the 2nd boost with Pbγ-spz or Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz, and analyzed as in (A). Results are from 1 of 3 representative experiments.

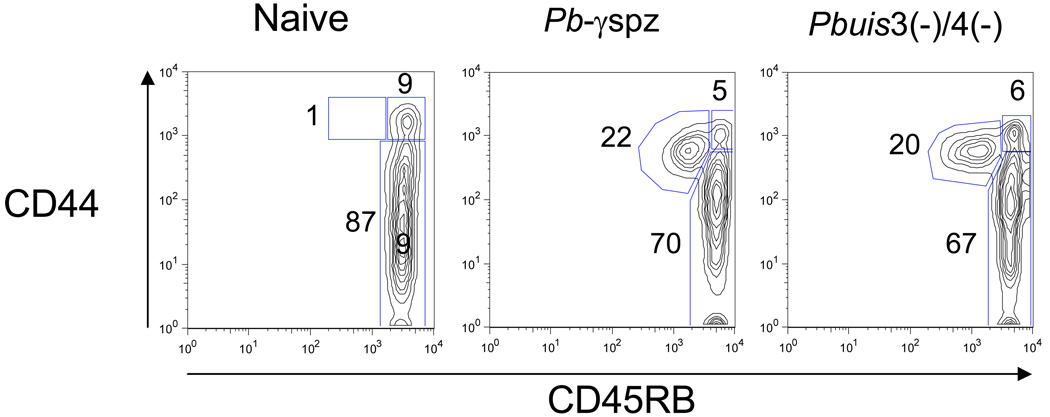

We also detected ~20 % of circulating CD8+ TEM cells in the blood 6 days after sporozoite challenge of both Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz- and Pbγ-spz-immune mice but not in the blood of naïve mice (Fig. 2B). These observations demonstrate the feasibility of using peripheral blood CD8+ T cell subsets as a surrogate indicator of hepatic CD8+ T cells in human subjects participating in malaria vaccine trials, including those planned with the double knock-out P. falciparum sporozoites.

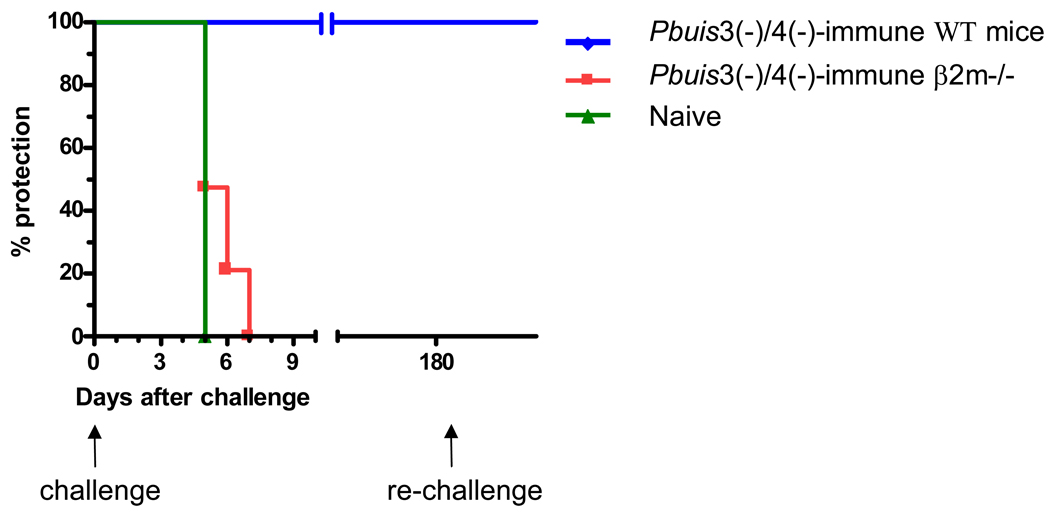

CD8+ T cells mediate protection against liver-stage infection in Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized mice

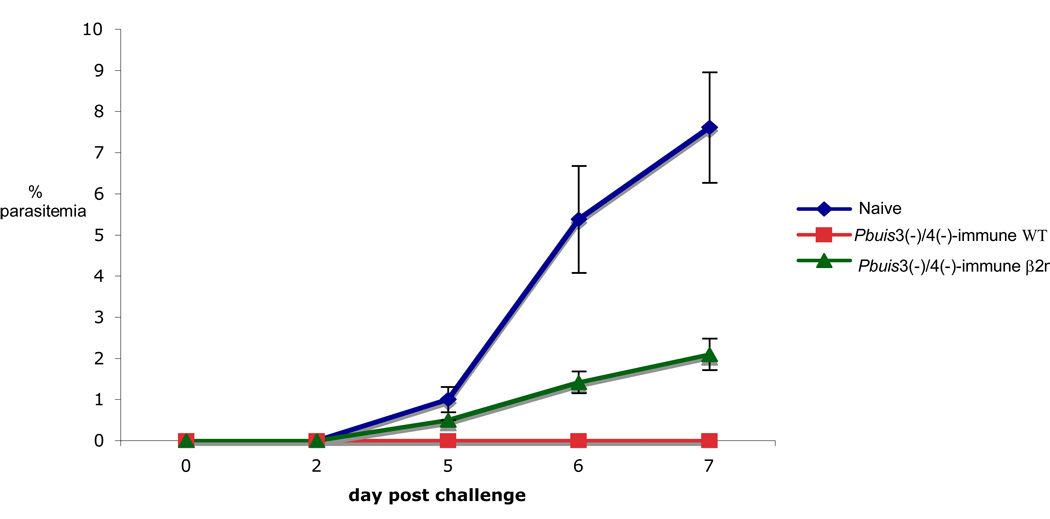

The relevance of the CD8+ T cells to Pbuis3(−)/4(−)spz-induced protection is not known and, therefore, we investigated their contribution using the CD8+ T cell deficient β2m−/− mouse model. Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized WT and β2m−/− mice were challenged with 10K sporozoites one week after the last immunization. As expected, Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune WT mice remained sterily protected. However, consistent with our observations with Pbγ-spz [17], all of the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized β2m−/− mice became parasitemic by day 7 after challenge (Fig. 3A). In contrast to naive WT mice, which developed parasitemia by day 5, the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized β2m−/− mice had a slight delay in the onset of parasitemia and by day 5 only 50% of mice were parasitemic. In addition, although the level of parasitemia in both groups was 1% at day 5, it increased in the WT naïve mice to 8% on day 7, while it remained at 2% in the β2m−/− mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Genetically-attenuated P. berghei fail to induce protective immunity in β2m−/− mice.

WT (n=5) and β2m−/− mice (n=19) were immunized with 75K, 20K and 20K Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz given one week apart. One week after the final immunization, mice were challenged with 10K infectious P. berghei spz. Naïve WT (n=5) were used as infectivity controls. Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune WT mice were re-challenged with 10K infectious P. berghei spz 6 months after the first challenge. Parasitemia was monitored by microscopy of Giemsa stained blood smears every other day, starting 2 days after challenge. (A) The percentage of mice remaining parasite-free at the indicated time points. (B) Results indicate the average % +/− SEM of parasitized red blood cells per mouse. Naïve WT control mice are indicated by a filled square and a solid line; immunized WT mice are indicated by a diamond and a broken line; immunized β2m −/− mice are indicated by a filled circle and a dashed line.

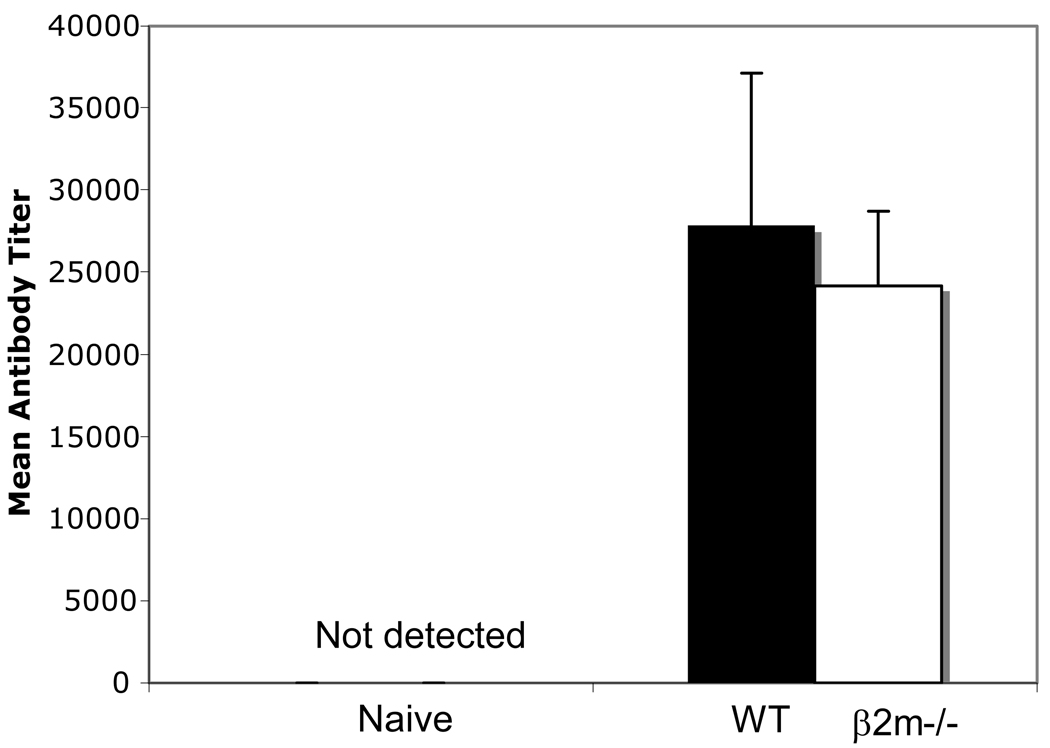

Although the failure to achieve sterile protection in β2m−/− mice likely stems from the absence of surface expression of MHC class I molecules hence CD8+ T cells, we wanted to rule out a possible defect in the Ab response as a contributor to this failure. It is well established that Pbγ-spz-induced protection is multifactorial [22] and that CD4 T helper cells [22] and B cells [23] play a significant role in mediating protective immunity. P. berghei CS protein-specific Ab titers of Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized β2m−/− and WT mice were 24,150 vs 27,875 respectively, and these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 4). We presume that the delayed onset and the lower level of parasitemia seen in the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized β2m−/− mice were controlled in part by the CS protein-specific Abs. This observation confirms previous findings from the Pbγ-spz [24] and Py-spz [25] models that although essential, Ab responses alone cannot mediate protection.

Fig. 4. Similar levels of anti-P. berghei CS protein antibodies in β2m−/− and WT mice.

β2m−/− (n = 5) and WT (n = 5) mice were immunized with 75K, 20K and 20K Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz given one week apart. Sera were obtained 6 days following tertiary immunization and assayed for anti-P. berghei CS protein antibodies by ELISA. Sera from naïve mice served as negative controls. Filled bar = WT mice; open bar = β2m −/− mice

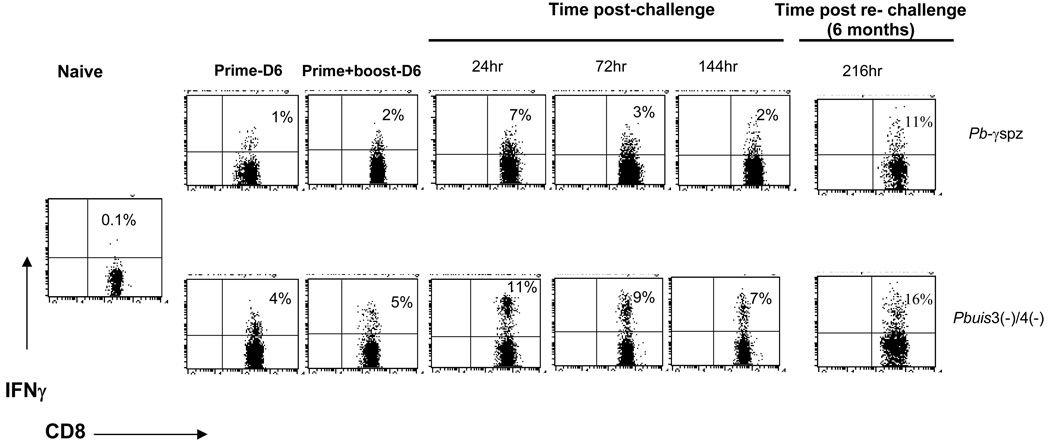

Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune CD8+ T cells are efficient IFN-γ producers

The exact mechanism by which CD8+ T cells confer protection is still not understood, although it is known that IFN-γ can mediate the destruction of liver-stage infection [16, 26] . We [12] and others [27] have demonstrated that IFN-γ-producing liver CD8+ T cells are linked to both induction and persistence of protective immunity. To determine whether Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced CD8+ T cells functioned similarly, we analyzed IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells after prime-boost immunizations with Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz and after infectious challenge. Immunizations with either Pbγ-spz or Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induced IFN-γ-producing hepatic CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5). However, priming with Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz induced a 4-fold higher response than Pbγ-spz (4% ± 1% vs 1% ± 0.2%) and following boost immunization a 2.5-fold increase (5% ± 1% vs 2% ± 1% ) was still evident. The peak response in both groups occurred at 24hrs post challenge, although the percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells at this time was 1.6-fold higher in the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz- vs. the Pbγ-spz -immune-challenged mice (11% ± 2% vs 7% ± 2%). The Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune-challenged mice continued to exhibit a more robust response than the Pbγ-spz -immune-challenged mice at 72hrs and 144hrs after challenge with an ~3-fold higher percentage of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells at both time points (9% ± 0.5% vs 3% ± 0.6% and 7% ± 0.2% vs 3% ± 0.5% at 72hrs and 144hrs, respectively). The fluorescence data also revealed a higher intensity of IFN-γ production by the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-induced CD8+ T cells compared with the Pbγ-spz-immune CD8+ T cells. Likewise, the attrition or contraction of the IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells was lower in the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz- than in the Pbγ-spz-immune mice. To determine the recall of memory responses, mice in both groups were re-challenged at 6 months, and CD8+ T cells were analyzed for IFNγ production. In the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-protected mice, 19% ± 2% of the hepatic CD8+ T cells produced IFNγ, while in Pbγ-spz-protected mice the IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells represented 14% ± 6% of the liver CD8+ T cells. The differences, however, were not statistically significant. IFNγ-producing hepatic CD8+ T cells were not detected in the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immune-challenged β2m−/− mice (data not shown).

Fig. 5. Higher frequency of IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells in the liver of Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-immunized vs Pbγ-spz-immunized mice.

HMC were isolated 6 days after both prime and prime-boost immunizations and at 24hr, 72hr, 144hr and 216hr after challenge from livers of Pbγ-spz or Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz immunized mice. IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells were identified by fluorescent labeling using an IFN-γ secretion assay (see Materials and Methods). The percentage of IFNγ-secreting T cells in the gated CD3+CD8+ T cell populations were determined by flow cytometry and are indicated in the upper quadrants. Dots plots are representative of 3 mice per group.

The data presented herein show for the first time that genetically-attenuated P. berghei sporozoites with double gene deletions induced protective immunity, which was long-lived and linked to MHC class I dependent, IFN-γ producing hepatic memory CD8+ T cells. Although both Pbγ-spz and Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz promoted differentiation of CD8+ T cells into phenotypically similar TEM and TCM cell subsets, collectively, the data suggest that the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz might be superior for the induction of protection. Although the mechanisms for this improved efficacy remain to be investigated, a number of scenarios could be considered. First, the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz might be more immunogenic than Pbγ-spz owing to differences in the state of the genes between the two parasite strains. Genetic attenuation disrupts specific genes creating homogenously arrested parasites, while attenuation by γ-radiation may damage genes randomly, leading to the loss of highly antigenic proteins. In addition, it is possible that genetic arrest is at a stage that best reflects the repertoire of protective Ags against subsequent transmission. In contrast, only a subpopulation of γ-spz might arrest at this point. Hence, relative to Pbγ-spz, the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz could produce a broader spectrum of parasite Ags, some with high binding affinities to MHC class I molecules, which might be reflected in the robust IFN-γ response.

The Pbuis3(−)/4(−) spz-derived proteins might engage antigen processing and presentation pathways more efficiently than proteins derived from Pbγ-spz. It is relevant that the UIS4-encoded protein is associated with the PV membrane [9] that surrounds the parasite subsequent to its invasion of hepatocytes. Although Pyuis4(−) parasites form a PV membrane (S. Kappe, manuscript in preparation), it is likely that the PV membrane has compromised function and may not protect the parasite from the host’s intracellular proteolytic enzymes, instead it might allow for a provision of a broader universe of antigenic proteins. Both the Pyuis3(−) and Pyuis4(−) parasites disappear by 40hrs after invasion (S. Kappe, manuscript in preparation), which might be partly explained by the leaky PV membranes surrounding the Pbuis3(−)/4(−) parasites. In turn it is also possible that the leaky membranes might trigger early apoptosis of the invaded hepatocytes, thus leading to efficient cross presentation by DC, of a wide spectrum of these liver-stage Ags [19] . Alternatively, some of these Ags may also be exported by the hepatocyte, possibly in the form of exosomes and subsequently taken up by DC for presentation to CD8+ T cells [28]. It should be also noted that long term retention of parasite antigens, possibly in the form of Ag-Ab complexes bound to follicular dendritic cells could account for protracted recruitment of CD8+ T cells subsequent to the demise/disappearance of the parasite.

Finally, 3 doses of 10K Pbuis3(−)/4(−) can protect against an infectious sporozoite challenge given 3 months after the last boost immunization without an intermittent infectious sporozoite challenge. In conclusion, these are compelling data in support of the genetically-attenuated Plasmodia as a pre-erythrocytic vaccine candidate and thus the development of genetically-attenuated P. falciparum parasites for the use in Phase Ia trials in humans is fully warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their appreciation to: Dr. D. Grey Heppner for his support and encouragement; Isaac Chalom, Gina Donofrio and Caroline Ciuni for the provision of hand dissected P. berghei sporozoites; the entire Krzych Lab for many useful discussions.

The views of the authors do not purport to reflect the position of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

U.K , S.H.I.K. and K.M. are partially supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through the Foundation at the National Institutes of Health Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative. This work was also supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health AI43411 (UK) and The U.S. Army Medical Research Command.

Abbreviations

- Pf

Plasmodium falciparum

- Pb

Plasmodium berghei

- Py

Plasmodium yoelii

- PV

parasitophorous vacuole

- UIS3 and UIS4

up-regulated in infective sporozoites genes 3 and 4

- γ-spz

radiation-attenuated sporozoites

- CS

circumsporozoite protein

Footnotes

Competing interests: S.H.I.K., K.M. and A.M. are inventors listed on U.S. Patent No. 7,22,179 and international patent application PCT/US2004/043023 each titled “Live Genetically Attenuated Malaria Vaccine.”

References

- 1.Breman JG, Alilio MS, Mills A. Conquering the intolerable burden of malaria: what's new, what's needed: a summary. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Alessandro U, Buttiens H. History and importance of antimalarial drug resistance. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:845–848. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulligan H, Russel FP, Mohan BN. Active immunization of fowls against Plasmodium gallinaceum by injections of heat killed sporozoites. J Mal Inst Ind. 1941;4:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clyde DF, Most H, McCarthy VC, Vanderberg JP. Immunization of man against sporozite-induced falciparum malaria. Am J Med Sci. 1973;266:169–177. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman SL, Goh LM, Luke TC, et al. Protection of humans against malaria by immunization with radiation-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1155–1164. doi: 10.1086/339409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellouk S, Lunel F, Sedegah M, Beaudoin RL, Druilhe P. Protection against malaria induced by irradiated sporozoites. Lancet. 1990;335:721. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90832-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvie O, Semblat JP, Franetich JF, Hannoun L, Eling W, Mazier D. Effects of irradiation on Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite hepatic development: implications for the design of pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines. Parasite Immunol. 2002;24:221–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2002.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller AK, Labaied M, Kappe SH, Matuschewski K. Genetically modified Plasmodium parasites as a protective experimental malaria vaccine. Nature. 2005;433:164–167. doi: 10.1038/nature03188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller AK, Camargo N, Kaiser K, et al. Plasmodium liver stage developmental arrest by depletion of a protein at the parasite-host interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3022–3027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408442102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikolajczak SA, Jacobs-Lorena V, Mackellar DC, Camargo N, Kappe SH. L-FABP is a critical host factor for successful malaria liver stage development. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheller LF, Azad AF. Maintenance of protective immunity against malaria by persistent hepatic parasites derived from irradiated sporozoites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4066–4068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berenzon D, Schwenk RJ, Letellier L, Guebre-Xabier M, Williams J, Krzych U. Protracted protection to Plasmodium berghei malaria is linked to functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous liver memory CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2024–2034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owusu-Agyei S, Binka F, Koram K, et al. Does radical cure of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum place adults in endemic areas at increased risk of recurrent symptomatic malaria? Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:599–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krzych U, Schwenk J. The dissection of CD8 T cells during liver-stage infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;297:1–24. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29967-x_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero P, Maryanski JL, Corradin G, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Zavala F. Cloned cytotoxic T cells recognize an epitope in the circumsporozoite protein and protect against malaria. Nature. 1989;341:323–326. doi: 10.1038/341323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss WR, Sedegah M, Beaudoin RL, Miller LH, Good MF. CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic/suppressors) are required for protection in mice immunized with malaria sporozoites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:573–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White KL, Snyder HL, Krzych U. MHC class I-dependent presentation of exoerythrocytic antigens to CD8+ T lymphocytes is required for protective immunity against Plasmodium berghei. J Immunol. 1996;156:3374–3381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wizel B, Houghten RA, Parker KC, et al. Irradiated sporozoite vaccine induces HLAB8-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against two overlapping epitopes of the Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite surface protein 2. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1435–1445. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Dijk MR, Douradinha B, Franke-Fayard B, et al. Genetically attenuated, P36p-deficient malarial sporozoites induce protective immunity and apoptosis of infected liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12194–12199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzych U, Schwenk R, Guebre-Xabier M, et al. The role of intrahepatic lymphocytes in mediating protective immunity induced by attenuated Plasmodium berghei sporozoites. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:123–134. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.00013h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahl K, Kim SK, Calcagno C, et al. IFN-induced attrition of CD8 T cells in the presence or absence of cognate antigen during the early stages of viral infections. J Immunol. 2006;176:4284–4295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nardin EH, Nussenzweig RS. T cell responses to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria: role in protection and vaccine development against pre-erythrocytic stages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:687–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egan JE, Hoffman SL, Haynes JD, et al. Humoral immune responses in volunteers immunized with irradiated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:166–173. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman SL, Oster CN, Plowe CV, et al. Naturally acquired antibodies to sporozoites do not prevent malaria: vaccine development implications. Science. 1987;237:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.3299709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar KA, Sano G, Boscardin S, et al. The circumsporozoite protein is an immunodominant protective antigen in irradiated sporozoites. Nature. 2006;444:937–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schofield L, Villaquiran J, Ferreira A, Schellekens H, Nussenzweig R, Nussenzweig V. Gamma interferon, CD8+ T cells and antibodies required for immunity to malaria sporozoites. Nature. 1987;330:664–666. doi: 10.1038/330664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sano G, Hafalla JC, Morrot A, Abe R, Lafaille JJ, Zavala F. Swift development of protective effector functions in naive CD8(+) T cells against malaria liver stages. J Exp Med. 2001;194:173–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delcayre A, Le Pecq JB. Exosomes as novel therapeutic nanodevices. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2006;8:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]