Abstract

Efforts to characterize the memory system that supports sentence comprehension have historically drawn extensively on short-term memory as a source of mechanisms that might apply to sentences. The focus of these efforts has changed significantly in the past decade. As a result of changes in models of short-term working memory (ST-WM) and developments in models of sentence comprehension, the effort to relate entire components of an ST-WM system, such as those in the model developed by Baddeley (Nature Reviews Neuroscience 4: 829–839, 2003) to sentence comprehension has largely been replaced by an effort to relate more specific mechanisms found in modern models of ST-WM to memory processes that support one aspect of sentence comprehension—the assignment of syntactic structure (parsing) and its use in determining sentence meaning (interpretation) during sentence comprehension. In this article, we present the historical background to recent studies of the memory mechanisms that support parsing and interpretation and review recent research into this relation. We argue that the results of this research do not converge on a set of mechanisms derived from ST-WM that apply to parsing and interpretation. We argue that the memory mechanisms supporting parsing and interpretation have features that characterize another memory system that has been postulated to account for skilled performance—long-term working memory. We propose a model of the relation of different aspects of parsing and interpretation to ST-WM and long-term working memory.

Keywords: Language/memory interactions, Language comprehension

Language comprehension requires memory over time scales ranging from deciseconds (in the case of sound categorization and word recognition) through several seconds and more (to accomplish sentence and discourse comprehension). This article critically reviews recent work on the memory system that supports one aspect of sentence comprehension—the assignment of syntactic structure (parsing) and its use in determining aspects of sentence meaning (interpretation)—and presents a new view of the memory systems that support these aspects of sentence comprehension.

Background

Even adjacent words must be assigned a syntactic relationship, and syntactic relations often span many words. For instance, in (1), the subject and object of grabbed, the subject of lost, and the antecedent of his must be retrieved at the points at which grabbed, lost, and his are encountered (or later, if parsing and interpretation is deferred):

-

1

The boy who the girl who fell down the stairs grabbed lost his balance.

Historically, the memory system that has been most often connected to parsing and interpretation is short-term memory (STM). The hypothesis that the memory system that supports parsing and interpretation utilizes STM is intuitively appealing because the temporal intervals over which parsing and interpretation usually apply are roughly the same as those over which STM operates. In addition, STM is an appealing construct to apply to sentence memory because it is thought to have capacity and temporal limitations that might account for the difficulty of comprehending certain sentences.

However, connecting STM to the memory system that supports parsing and interpretation has proven to be difficult. Kane, Conway, Hambrick, and Engle (2007) introduced a chapter on variability in working memory with the comment that “failed attempts to link STM to complex cognitive functions, such as reading comprehension, loomed large in Crowder’s (1982) obituary for the concept” (p. 21). Kane et al. went on to say that Baddeley and Hitch (1974) “tried to validate immediate memory’s functions” by introducing the concept of working memory (which we will call short-term working memory [ST-WM]). Evidence for a functional role for ST-WM came from interference from concurrent six-, but not three-, item memory loads in reasoning, comprehension, and learning tasks, which suggested that “small memory loads are handled by a phonemic buffer … whereas larger loads require the additional resource of a central executive. Thus working memory was proposed to be a dynamic system that enabled maintenance of task-relevant information in support of the simultaneous execution of complex cognitive tasks” (Kane et al., 2007. p. 21).

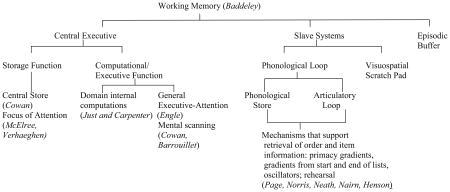

Baddeley’s model of ST-WM represents one influential model among many models of short-term and working memory. We begin this article with an overview of models of these memory systems, beginning with Baddeley’s, which was directly related to sentence comprehension. A guide to terminology and the evolution of models is found in Box 1.

Box 1. Components and processes in models of short-term working memory. This chart summarizes features of models of short term memory, illustrating how components of Baddeley’s “working memory” model are related to other constructs. The outline does not present all models and all mechanisms; it shows aspects of models that are mentioned in the text.

Baddeley’s initial model of ST-WM (e.g., Baddeley, 1986) contained two major components. A central executive (CE) maintained multidimensional representations and was also considered to have some computational functions (see below). Visuospatial and verbal slave systems maintained domain-specific representations. The verbal slave system, the phonological loop (PL), consisted of two components: a phonological store (PS) that maintained information in phonological form subject to rapid decay and an articulatory mechanism that rehearsed items in the PS and transcoded written verbal stimuli into phonological form. Baddeley (2000) introduced a third type of store: the episodic buffer (EB), which retained integrated units of visual, spatial, and verbal information marked for temporal occurrence. The slave systems and the EB had no computational functions themselves.

From approximately 1980 to 2000, a number of researchers sought to relate the memory system that supports aspects of sentence comprehension to components of the model of ST-WM developed by Baddeley and his colleagues. The main question that was considered was what component(s) of the ST-WM system, if any, supported aspects of sentence memory; as has been noted, our focus is on the sentence memory that supports syntactic comprehension. Either the CE or the PL could play this role (the role of the EB, which had not been introduced at the time much of this work was done, has not been investigated). The CE maintains abstract representations that could include syntactic and semantic information, making it suitable for this purpose. The PL maintains phonological representations that are linked to lexical items that contain the needed semantic and syntactic information, and it might be easier for the memory system to maintain such representations in the PL as pointers to the needed information than to maintain what are arguably more complex representations in the CE.1

Data regarding these possibilities come from several sources: interference effects of concurrent tasks that require the CE or the PL on parsing and interpretation (King & Just, 1991;Waters, Caplan, & Hildebrandt, 1987); tongue twister effects (Acheson & Macdonald, 2011; Ayres, 1984; Keller, Carpenter, & Just, 2003; Kennison, 2004; McCutcheon, Bell, France, & Perfetti, 1991; McCutcheon & Perfetti, 1982; Perfetti & McCutchen, 1982; Zhang & Perfetti, 1993); effects of homophones on comprehension (Coltheart, Patterson, & Leahy, 1994; Waters, Caplan, & Leonard, 1992); correlations between measures of the capacity of the CE and performance in parsing and interpretation (Just & Carpenter, 1992; King & Just, 1991; MacDonald, Just, & Carpenter, 1992; Miyake, Carpenter, & Just, 1994; Waters & Caplan, 1996); associations and dissociations of effects of brain damage on the CE or the PL and parsing and interpretation (Caplan & Waters, 1996; Emery, 1985; Grossman et al., 1991; Grossman, Carvell, Stern, Gollomp, & Hurtig, 1992; Kontiola, Laaksonen, Sulkava, & Erkinjuntti, 1990; Lalami et al., 1996; Lieberman, Friedman, & Feldman, 1990; R. C. Martin, 1990; Natsopoulos et al., 1991; Rochon & Saffran, 1995; Rochon, Waters, & Caplan, 1994; Stevens, Kempler, Andersen, & MacDonald, 1996; Tomoeda, Bayles, Boone, Kaszniak, & Slauson, 1990; Waters, Caplan, & Hildebrandt, 1991; Waters, Caplan, & Rochon, 1995); and neural evidence in the form of differences in neural activation in high-and low-span participants during parsing and interpretation and overlap or nonoverlap of brain areas activated in tasks that involve the CE and ones that involve parsing and interpretation (Fiebach, Schlesewsky, & Friederici, 2001; Fiebach, Vos, & Friederici, 2004). In Caplan and Waters (1990), we argued that these sources of data suggested that the PL did not support the memory requirements of the initial assignment of the preferred structure and interpretation of a sentence (what we called first-pass parsing and interpretation) but may play a role in supporting review and reanalysis of previously encountered information and in using the products of the comprehension process to accomplish a task (e.g., in maintaining a sentence in memory to later answer a question about its meaning). We think that it is fair to say that there is a general consensus that this view is correct; for example, in an article relating the memory system that supports syntactic comprehension to ST-WM, Just and Carpenter (1992) explicitly said that they were not advocating a role for the PL, but only the CE, in this process. The role of the CE in parsing and interpretation has been more controversial. In Caplan and Waters (1999), we argued that evidence of the sort described above indicated that, like the PL, the CE does not support first-pass parsing and interpretation, but other researchers have disagreed (Just & Carpenter, 1992).

We will not revisit this literature because developments in models of ST-WM have radically changed constructs in Baddeley’s model of ST-WM. Phonological effects in immediate serial recall and other STM tasks have been discredited as evidence for storage of purely phonological representations (Jones, Hughes, & Macken, 2006, 2007; Jones, Macken, & Nicholls, 2004; see Caplan, Waters, & Howard, 2012, for a review). Neuropsychological data have provided evidence that lexical representations, including semantic features, not purely phonological representations, are stored in ST-WM (N. Martin & Ayala, 2004). These changes have effectively eliminated the PS. Duration-based word length effects in immediate serial recall have been found to be due to lexical properties of words—in particular, neighborhood size (Jalbert, Neath, & Surprenant, 2011)—undermining a critical piece of evidence for a role for articulatory-based rehearsal in sustaining decaying phonological representations. Some contemporary models of ST-WM include a rehearsal mechanism that applies to multidimensional representations (Burgess & Hitch, 1992, 1999; Page & Henson, 2001), a significant departure from the PL model. Many modern models postulate an important role for a mental refreshing process in maintaining representations in ST-WM (Barrouillet, Bernardin, & Camos, 2004). This mechanism is not part of Baddeley’s PL.

The notion of the CE has also undergone changes. One line of research has investigated its computational function. Baddeley and Hitch (1974) limited the computational role of the CE to control processes, attributing domain-specific computations to domain-specific processors. Most recent work has accepted this view and has explored the role of domain-independent executive functions of the CE in supporting performance on memory tasks (Barrouillet et al., 2004; Engle, Kane, & Tuholski, 1999; Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999; Oberauer & Lewandowsy, 2011). The mental refreshing process mentioned above can be seen as one way the CE supports ST-WM; the CE has also been said to support ST-WM by strategically transferring items between primary and secondary memory (Engle, Kane, & Tuholski, 1999; Engle, Tuholski, et al., 1999). Engle and his colleagues have argued that the functional role of the domain-independent executive functions of the CE extends beyond supporting performance on memory tasks to the point of being a major determinant of “fluid intelligence.” They have suggested that the combination of storage and the executive functions of task goal maintenance and inhibition of competing responses constitute an integrated “executive attention” capacity that “is specifically responsible for the covariation between measures of WM and higher order cognition” (Kane & Engle, 2003, p. 47).

Other investigators have conceived of the computational functions of the CE as supporting domain-specific cognitive functions as well as domain-independent executive attention (Craig & Lewandowsky, in press). In the area of sentence comprehension, Just and Carpenter (1992) modeled behavioral results in sentence comprehension in terms of the load exerted on a single “resource” by both memory and computational requirements of parsing and interpretation and argued that that resource was the CE. Just and Carpenter developed a model in which resources could be flexibly allocated to computations (parsing operations) or storage to minimize the effects of overload. However, there have been no other models of this type that specifically relate both computational and storage functions of the CE to parsing and interpretation.

The aspect of the CE that has been examined in recent studies and that has been related to parsing is its memory component. As was noted, Baddeley’s CE includes a limited-capacity memory store of multidimensional representations, which can be accessed by the parser. This store, which has been named the central store (CS; Cowan, 2000; Ricker, AuBuchon, & Cowan, 2010), has been studied separately from the attentional/executive/computational functions of the CE. Entry of items into the CS depend upon attention (Cowan, 1995), but this aspect of the functioning of the CS has not been related to memory used in sentence comprehension (all recent studies have involved attended sentences). The capacity of the CS and the nature of retrieval of items from the CS have been related to the memory processes used in sentence comprehension—in particular, the memory system that supports parsing and interpretation. We now therefore turn to studies of the CS.

The Central Store

The CS is a relatively new concept in theories of STM. As has been noted, it does not correspond to any construct in Baddeley’s working memory model, differing from the CE in not having an executive or computational function and from the EB in not binding different items into an episodic unit. It has some similarity to the constructs of primary memory (PM) and secondary memory (SM) in the pre-Baddeley literature (James, 1890) but differs from both. It is similar to PM in that it is capacity limited. It differs from conceptualizations of PM that maintain that PM contains phonological representations (Colle, 1980; Colle & Welsh, 1976; Conrad, 1963, 1964; Shallice, 1975; Shallice & Vallar, 1990) and is more similar to conceptualizations of PM that maintain that PM contains multidimensional representations (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Craik, 1970; Craik & Levy, 1970). The CS is similar to SM because it contains multidimensional representations and constitutes the activated portion of long-term memory (LTM; see below), but it differs significantly from SM because of its limited capacity. In this section, we briefly outline recent views regarding the capacity of the CS and retrieval of items in STM tasks.

The capacity of the CS has been estimated on the basis of accuracy and speed of recall data. Using tasks that prevent the persistence of sensory stores and the use of rehearsal, the capacity of the CS based on accuracy has been estimated at three to five items (see Cowan, 2000, for a review). For instance, Saults and Cowan (2007) exposed participants to four spoken digits presented in four different voices by loudspeakers in four spatial positions and four colored spots presented at four different locations in a recognition task. Participants recognized three to four items regardless of whether only the visually presented colors or both the visually presented colors and the auditorily presented digits had to be remembered.

Temporal data result in a similar, although more subtle, picture. Verhaeghen and Basak (2005) found that RTs in the n-back task showed an increase from n = 1 to n = 2 and no changes from n = 2 to n = 5. On the assumption that shifts to items outside the focus of attention incur a cost seen in reaction times (RTs) when accuracy is near ceiling, they argued that only one item was maintained in the focus of attention in this task. However, Verhaeghen, Cerella, and Basak (2004) showed that the point at which RTs began to increase was increasingly displaced toward n = 5 with increasing practice with the task. Verhaeghen et al. (2007) argued that the difference in RTs between n = 4 and n = 5 even in highly practiced tasks suggests an upper bound of four on the number of items that can be maintained in the focus of attention. This number is consistent with Cowan’s (2000) conclusion regarding the capacity of the CS, although the fact that an expanded focus of attention requires practice on a task differs from Cowan’s (2000) view of the capacity of the CS.

The capacity of ST-WM has also been studied through the analysis of speed–accuracy trade-offs (SATs). In the SAT approach, participants are presented a stimulus, followed by a probe at a variable lag, and are required to make a two-alternative forced new–old choice within a very short time (usually less than 200 ms; responses less than 100 ms are discarded as anticipations). Asymptotic d′ is considered to be a measure of the availability of an item, and the temporal point at which d′ rises above 0 (the intercept) and the slope of the rise of d′ from the point at which it rises above 0 to its asymptotic level reflect how an item is accessed. McElree and Dosher (1989) found that set size (three and five) affected asymptotic accuracy but not temporal dynamics, except for the set-final item, even when the probe was presented in a different font. McElree (1998) found that there were different retrieval speeds for probes drawn from the last and all other categories when triads of words in different semantic categories were presented. McElree (1996) found that recognizing rhyming words and semantically related words resulted in uniformly slower dynamics than did recognizing previously presented words as wholes. McElree (2006) argued that ST-WM consisted of a focus of attention with one item, which was accessed by a matching procedure based on abstract (nonsensory) features of the retrieval cue, and items outside the focus of attention, in LTM, that were accessed by a content-addressable retrieval mechanism, with chunking of the memory set in accordance with semantic features.

There are important differences among these models regarding the capacity-limited portion of ST-WM. Cowan (2000) argued for a tripartate division of memory, in which items could be in focal attention, in an activated part of LTM outside of focal attention (the CS), or in LTM. McElree (2006) and Verhaeghen et al. (2007) argued for a bipartate division of memory into a state of focal attention and LTM. These models do not include a CS. McElree’s (2006) estimate of the capacity of the focus of attention as one chunk is consistent with results for unpracticed trials of the n-back task reported by Verhaeghen and Basak (2005) but is inconsistent with the expanded capacity of this “store” after practice and with the existence of a CS.

The capacity limit of ST-WM, whether the CS or the focus of attention, is important because, as Lewis (1996) has emphasized, syntactic processing requires at least two items. Therefore, both the CS and an expanded focus of attention provide a capacity-limited memory store that could both satisfy the demands of parsing for access to more than one representation and also impose limits on parsing related to the availability of information, but McElree’s (2006) capacity-limited part of ST-WM (the focus of attention), which is limited to one item, cannot support parsing.2 McElree’s (2006) model therefore entails that parsing involves retrieval from LTM and is not capacity limited, a position that McElree endorses (McElree, personal communication, University of Massachusetts Workshop on Parsing and Memory).

These studies also provide information about the nature of retrieval of items in the different stores available in STM tasks. In general, items could be retrieved by matching features of all items in memory against those of a retrieval cue and selecting the best match (content-addressable retrieval) or by searching for one or more items with particular features (search). Search could proceed in many ways. We consider items inside and outside the limited-capacity portion of ST-WM separately.

McElree (2006) suggested that items within the focus of attention were accessed by direct matching. Verhaegen et al. (2007) considered items in their expanded focus of attention by analyzing the time to report items in the practiced trials of the n-back task reported in Verhaegen et al. (2004). There was a 30-ms/item increase over the n = 1 to n = 4 range, and an ex-Gaussian decomposition of the RT data indicated that the effect was due to changes in the skew of the distribution of RTs (τ). These features suggest a limited-capacity parallel search process, not a content-addressable process. It has also been argued that items within the focus of attention that are not grouped into a higher level chunk are not content addressable but require search to be retrieved (Basak, 2005; Hockley, 1984, Experiment 1; Trick & Pylyshyn, 1994; Verhaeghen et al., 2007).

The flat RT curves for items outside the focus of attention in the work by Verhaeghen and his colleagues cited above are consistent with a content-addressable retrieval model for those items, as are the uniform SAT dynamics for these items reported by McElree and his colleagues. Verhaegen et al. (2007) pointed out, however, that substantial slopes of RTs-over-n for n above the step function have been described for older participants (Basak, 2005) and in unpracticed trials in younger participants when the item to be matched could be any one between 1 and n back. These slopes are much steeper than the ones found for items within the focus of attention and are best modeled by changes in the skew, mean, and standard deviation in ex-Gaussian models, pointing to a search process. McElree (2001) also studied SAT functions for recognition of items either 2 or 3 back in an n-back test and concluded that the best model of the temporal dynamics in this situation was a mixed model, in which some items were accessed by a content-addressable memory and some by a serial search process, and that the extent to which these two mechanism applied differed in different individuals. Verhaeghen et al. (2007) concluded that items outside the focus of attention are content addressable only under what they called “ideal” circumstances—precisely, predictable switching out of the focus of attention on the part of high-functioning individuals—and require search under other circumstances. Items outside the focus of attention are also not content addressable but require search when order, as well as item information, must be retrieved (Hockley, 1984, Experiment 3; McElree & Dosher, 1993).

Despite these differences in models and results, two features of modern models have been considered to be well enough established to warrant exploration as memory mechanisms in sentence comprehension: (1) the notion that a small number of items —at most, four or five— are maintained in a highly accessible form and that this number of available items sets a capacity limit in parsing and interpretation and (2) the view that retrieval of information in parsing and interpretation is content addressable. We shall review studies that suggest that these features of memory are found in parsing and interpretation (see the Mechanisms in ST-WM and Parsing and Interpretation: Empirical Results and Interpretation section).

Retrieval-based parsing

A model of parsing and interpretation that specifies when and how memory is utilized is needed to relate ST-WM to parsing and interpretation. Models that specify such mechanisms in parsing and interpretation have recently been developed in work on retrieval-based parsing. We shall briefly outline the model developed by Lewis and his colleagues, which is one of the most widely cited models (see Lewis, Vasishth, & Van Dyke, 2006, for a summary).

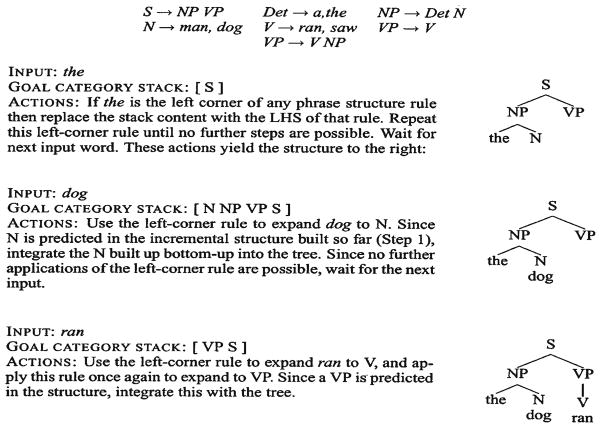

Lewis and his colleagues’ model utilizes Anderson’s ACT-R framework (Anderson, 1976). Information about syntactic structure is maintained in long-term declarative memory as symbols consisting of feature-value pairs. In Lewis and Vasishth (2005), each symbol represents a maximum syntactic projection (the categories are drawn from Chomsky, 1995), and the features include syntactic information about the category (e.g., whether it takes a specifier, head, complement), as well as other syntactic features. Lexical items, containing syntactic information, are also listed in declarative memory. Parsing begins with lexical access, which places a new word and its features in a lexical buffer. Production rules then combine information in the lexical buffer with information in the accruing syntactic representation, based on information about structures of the language that are maintained in declarative memory. The production rules follow a left-corner parsing process: Given a lexical input and a goal category, the input is replaced with the left side of a rewrite rule that then applies, and the process is repeated until no further rules apply (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Rewrite rules from Lewis and Vasishth (2005, Fig. 3)

The phrase marker created by a production rule is stored in a problem state buffer, and the categories that are needed to complete phrase markers in this buffer are stored in a control buffer. Items in the problem buffer decay over time. The syntactic features of the current lexical entry and the structure in the control buffer combine to form retrieval cues, which may retrieve previously constructed constituents or symbols in LTM. On the basis of the retrieved item and the current lexical content, a production creates a new syntactic structure and attaches it to the retrieved constituent. This increases the activation of previously constructed constituents and thereby partially or, at times, fully counteracts the effect of temporal decay. The control buffer is updated, and a production rule then guides attention to the next word.

The retrieval process for lexical items and syntactic symbols in declarative memory is content addressable. It consists of matching features of a retrieval cue to features of items in the memory set. Retrieval success is determined by the ratio of the resonance of the retrieval cue with the retrieved item divided by its resonance with other items in the memory set (Nairne, 1990a; Ratcliff, 1978), subject to noise. This model has two features: (1) Items in the memory set that share features with a retrieval cue interfere with retrieval of a target, and (2) shared features of items in the memory set do not affect retrieval unless these features are part of the retrieval cue.

These developments in models of ST-WM and parsing specify mechanisms in ST-WM that can apply to parsing and interpretation. Work in the past 15 years has made connections between these mechanisms and parsing and interpretation. In the next section, we review research into three phenomena—interference effects, retrieval dynamics, and capacity limitations—that have been interpreted as providing a mutually consistent set of results that establish such links. In the A Critical Look at the Evidence Regarding Features of Retrieval-Based Parsing section, we will argue that, despite its important contributions to describing and modeling new phenomena, the effort to relate these phenomena to mechanisms in ST-WM encounters significant problems. In the An Alternative Framework for Viewing the Memory System for Parsing and Interpretation section, we outline a different perspective on the memory system that supports parsing and interpretation.

Mechanisms in ST-WM and parsing and interpretation: Empirical results and interpretation

In this section, we selectively review representative results that bear on the nature of memory processes in parsing and interpretation. The range of results is summarized in Box 2, along with issues we shall raise in later sections.

Box 2. Phenomena and issues in studies of the memory processes that support parsing and interpretation (with sections of the article where the topic is discussed).

| Empirical phenomenon | Issues raised |

|---|---|

| I. Semantic interference effects (Semantic Similarity Effects) | |

| a. of items in lists (Similarity of External Load Load to Sentence-Internal Items) |

|

| b. of items in sentences (Similarity of Sentence-Internal Items to One Another) |

|

| II. Syntactic Interference Effects (Syntactic Interference Effects) |

|

| III. SAT results (Retrieval Dynamics) |

|

| IV. Capacity Limitations (Capacity Limits and Temporal Decay) |

|

| V. Temporal Decay (Capacity Limits and Temporal Decay) |

|

| VI. Other issues |

|

Interference effects in parsing and interpretation

The first set of studies we shall review are ones that document what have been interpreted as interference effects in retrieval during parsing and interpretation. Two types of interference effects have been described in parsing and interpretation and related to retrieval mechanisms described in ST-WM: those due to semantic features of the items in memory and those due to syntactic features of those items.

Semantic similarity effects

Effects of the semantic similarity of noun phrases on online sentence processing measures have been described for both sentence-internal and sentence-external noun phrases.

Similarity of external load to sentence-internal items

Two studies have been said to show that semantic properties of noun phrases in a sentence and in a to-be-recalled list affect processing times for verbs of relative clauses more in object-than in subject-relative clauses. On the assumption that the verb of an object-relative clause creates a retrieval cue for the noun phrases that serve as its subject and object, whereas the verb of a corresponding subject-relative clause cues only retrieval of its subject, a superadditive interaction between semantic properties (similar, dissimilar) and sentence type (subject or object relative) has been interpreted as being due to interference of semantically similar nouns on retrieval in parsing and interpretation.

Gordon et al. (2002) presented word lists consisting of either three proper nouns (Joel, Andy, Greg) or three common nouns (banker, lawyer, accountant) for recall while participants self-paced their way through cleft subject and cleft object sentences (2), which also contained either proper nouns or common nouns.

-

2

Subject cleft: It was Sam (the manager) that liked Tony (the clerk) before the argument began.

Object cleft: It was Sam (the manager) that Tony (the clerk) liked before the argument began.

The difference in reading times for semantically matched and unmatched list/sentence pairs was numerically greater for object than for subject relatives.

Fedorenko, Gibson, and Rohde (2006) had participants recall either one or three common or proper nouns and self-pace themselves through sentences with subject- or object-relative clauses (3) containing common nouns in a verification task.

-

3

Subject relative: The physician who consulted the cardiologist checked the files.

Object relative: The physician who the cardiologist consulted checked the files.

The interaction of list type and syntactic structure on reading times for the relative clause was significant: The effect of match (longer reading times when participants recalled matching, as compared with nonmatching, lists) was found only in the object-relative clauses in the three-item list condition.

A third study of external load has been taken to show that semantic properties of NPs in to-be-recalled lists interfere with retrieval of NPs in object-relative clauses when they have semantic features specified in the retrieval cue. Van Dyke and McElree (2006) reported self-paced reading times for object clefts with or without concurrent recall of sets of three words that could or could not be integrated into the sentence, as in (4):

-

4

Word list: table–sink–truck

Sentence: It was the boat that the guy who lived by the sea sailed/fixed in two sunny days.

At the verb of the embedded clause, there were longer reading times in the integrated (fixed) than in the unintegrated (sailed) load conditions.

Similarity of sentence-internal items to one another

The second set of semantic similarity effects involves sentence-internal noun phrases. Gordon et al. (2001) reported self-paced reading times in subject- and object-extracted relative clauses (5a, 5b) and clefts (6a, b) with common nouns (definite descriptions), proper nouns, or pronouns:

-

5

The banker that praised the barber/Sue/you climbed the mountain…

The banker that the barber/Sue/you praised climbed the mountain…

-

6

It was the banker/Sue that praised the barber/Dee…

It was the banker/Sue that the barber/Dee praised…

In the relative clauses (5a, 5b), the sentence type effect was reported as being greater in the definite description (the barber) condition than in either the pronoun (you) or the proper name (Sue) condition. In clefts (6a, 6b), there was a greater sentence type effect in sentences in which the NPs were matched for noun type (both definite descriptions or both proper nouns) than in sentences in which they differed. In a follow-up study, Gordon, Hendrick, and Johnson (2004) reported that there was a reduction in the object extraction cost in sentences with two definite descriptions when the relative-clause-internal NP was a quantified pronoun (everyone), but not when it was modified by an indefinite article (a barber) or was a generic noun (barbers) or a superordinate term (the person). Gordon and his colleagues argued that these results could be explained if the verb of an object-relative clause is a retrieval cue for two noun phrases and their order and the verb of a subject-relative clause is a retrieval cue for only one noun phrase. Gordon, Hendrick, and Johnson (2001) argued that “memory for order information is impaired when the items to be remembered are similar because the similarity of the items causes interference in retrieving the order information (Lewandowsky & Murdock, 1989; Murdock & Vom Saal, 1967; Nairne, 1990b) (p. 1420)”.

Syntactic interference effects

Lewis and his colleagues (Lewis, 1996, 2000; Lewis & Vasishth, 2005; Lewis et al., 2006; Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003; Vasishth & Lewis, 2006) have shown that syntactic features of lexical items that intervene between a retrieval cue and the item to be retrieved affect online processing. As in the work by Gordon and his colleagues that we have discussed, these results have been presented as evidence that principles that govern interference in ST-WM models also apply in sentence processing. Lewis and his colleagues have modeled a variety of phenomena in both comprehension and online performance in terms of retrieval-based syntactic interference, including effects of repetition of the same structure, some ambiguity effects, some embedding effects, some “locality” effects, and some “antilocality” effects (Vasishth & Lewis, 2006, present several results). We will describe the phenomenon by presenting one study that is often cited as an example of these effects (Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003).

Van Dyke and Lewis (2003) presented sentences such as (7)–(9). Words in parentheses were omitted in half the presentations of the sentences to produce ambiguities; we have annotated some words with subscripts for ease of reference.

-

7

Short distance:

The secretary forgot (that) the student was2 standing in the hallway.

-

8

Long distance, low interference:

The secretary forgot (that) the student who was1 waiting for the exam was2 standing in the hallway.

-

9

Long distance, high interference:

The secretary forgot (that) the student who knew (that) the exam was1 important was2 standing in the hallway.

Van Dyke and Lewis’s focus was on retrieval of the student as the subject of was standing when was standing was encountered.

Sentences (7) versus (8) and (9) vary the distance between the student and was standing. The critical sentences for syntactic interference effects are (8) versus (9), which vary the syntactic nature of the items between was standing and the student, holding distance constant. We focus here on the unambiguous versions, in which the student is assigned the role of subject when it is first encountered (the ambiguous versions will be discussed below). If was standing is a retrieval cue for a subject, there will be more syntactic interference with retrieval of the student in (9) than in (8) because the exam is a subject in (9) and an object in (8). Van Dyke and Lewis (2003) presented four studies of accuracy and self-paced reading times in an acceptability judgment task with these sentences. In the three of the four studies in which unambiguous versions of these sentences were presented, there was greater acceptance of the well-formednes of (8) than of (9) and longer self-paced reading times for the critical segment was2 in (9) than in (8). The difference between the unambiguous versions of sentences (8) and (9) is consistent with the claim that retrieval cues include syntactic features of items and with the model of interference described in the Retrieval-Based Parsing section. Similar effects of whether an NP intervening between a verb and its subject was in subject or object position were described by Van Dyke and McElree (2011) for reading times and for asymptotes of SAT functions (see below) in sentences where matrix verbs were the retrieval cues.

Retrieval dynamics

McElree and his colleagues have reported a series of studies using the SAT technique that led them to the conclusion that the dynamics of search through memory are similar for items in sentences and in lists. In this application of the SAT paradigm, participants are required to make judgments about the acceptability of sentences. To study retrieval, the last word in the experimental sentence serves as a retrieval cue for an earlier word, and the position of the retrieved word and the number and type of potentially interfering items are varied across sentence types. Asymptotic d′ is taken as a measure of the availability of the earlier word and d′ dynamics as the measure of its accessibility.

McElree and his colleagues have used the SAT technique to study many types of sentences. A. E. Martin and McElree’s (2008, 2009) work on verb phrase ellipsis such as (10), in which the antecedent of the elided verb phrase cannot be anticipated, produced characteristic results. A. E. Martin and McElree varied the distance between the ellipsis and the antecedent (10a, 10b), the length and complexity of the antecedent (10c, 10d), and the amount or proactive or retroactive interference (10e, 10f).

-

10

The editor admired the author’s writing but the critics did not.

The editor admired the author’s writing but everyone at the publishing house was shocked to hear that the critics did not.

The history professor understood Roman mythology but the principal was displeased to learn that the overworked students attending the summer school did not.

The history professor understood Rome’s swift and brutal destruction of Carthage but the principal knew that the over-worked students attending the summer school did not.

Even though Claudia was not particularly angry, she filed a complaint. Ron did too.

Claudia filed a complaint and she also wrote an angry letter. Ron did too.

None of these variables affected SAT dynamics, indicating that retrieval is unaffected by the amount of proactive or retroactive interference or the complexity of the retrieved item. This implies that retrieval uses a content-addressable mechanism, similar to findings in ST-WM reviewed above.

Capacity limits and temporal decay

The idea that parsing is capacity limited has been part of thinking about sentence comprehension for decades (Miller & Chomsky, 1963), and if it is correct that capacity limitations of the parser/interpreter are those found in the capacity-limited portion of ST-WM, this would tie a major feature of parsing and interpretation to a property of ST-WM. Lewis and his colleagues have proposed several such relations.

One is a limit on the number of items of the same type that can be maintained in a syntactic buffer. Working within the SOAR architecture (Newell, 1990), Lewis (1996) developed a model in which lexical items can either be heads or dependents (or both) in structural relations. For instance, in the phrase under the basket, under can be the head of the relation complement of a preposition ([COMP P]), and the basket can be the dependent of the relation complement of a preposition ([COMP P]). When under is encountered, the structure [HEAD –COMP P–under] is placed in a buffer containing head/dependent sets; when the basket is encountered, the structure [DEPENDENT–COMP P–the basket] is created. Parsing consists of connecting heads and dependents under higher nodes. When both under and the basket are encountered, the two structures are combined into a single node [[HEAD–COMP P–under] [DEPENDENT–COMP P–the basket]].

Lewis (1996) argued that capacity limits on parsing arise because the buffer can contain only two constituents of the same type. For instance, in an object-relative clause such as (2b), repeated here for convenience,

-

2b

It was the manager that the clerk liked before the argument began,

when the clerk is encountered, the buffer contains the structure [DEPENDENT–SPEC-IP–the manager; the clerk], which is within the capacity of the buffer. However, in the doubly center-embedded structure (11),

-

11

It was the book that the editor who the secretary who quit married enjoyed, at the secretary

the buffer contains the structure [DEPENDENT–SPEC-IP–the book; the editor; the sectretary], and the sentence becomes difficult because three NPs in the buffer are assigned the value [DEPENDENT–SPEC-IP].

A critical look at the evidence regarding features of retrieval-based parsing

As has been noted, results such as those presented above have been taken as evidence for links between ST-WM and the memory processes that apply in parsing and interpretation. The conclusion that has been suggested is that retrieval of information in parsing and interpretation makes use of a content-addressable retrieval process that derives from retrieval of information in ST-WM and that some parsing limitations are derived from capacity limitations of ST-WM. In this section, we critically consider these results and conclusions.

Empirical issues in results

We begin by noting several weaknesses in some of the empirical results reviewed above.

Empirical issues in studies demonstrating semantic interference effects

Several results cited above were not significant by conventional standards. In the Gordon et al. (2002) study (sentences 2a, 2b), the critical interaction did not approach significance, F1 = 2.4, p = .13; F2 = 1.7, p = .19. The interaction of description/proper-noun condition with structure in relative clauses in Gordon et al. (2001; sentences 5a, 5b) was not significant when the entire relative clause was considered, and differences in length of the clause-final NP in subject- and object-relative clauses could account for the differences when only clause-final words were compared (comparing praised with the barber would be expected to produce less of an effect than comparing praised with Sue). The interaction of noun type (matched, mismatched) with structure in clefts in Gordon et al. (2001; sentences 6a, 6b) was significant only in the analyses by participants. In Fedorenko et al. (2006; sentences 3a, 3b), all sentences contributed to online reading time analyses despite the fact that accuracy in answering the two questions that were asked about each sentence was only 55%.

In two studies, some results were unexpected. In Fedorenko et al. (2006), the difference between reading times for subject and object sentences in the segment that followed the relative clauses in the one-word list condition was larger in the mismatch than in the match conditions, the opposite of what retrieval interference would predict, and the object-relative cost was greater when participants recalled one-word than when they recalled three-word non-matching lists, suggesting that reading times for the object-relative verb were reduced in the three-word nonmatching condition because of strategic choices made regarding performance on the list and sentence comprehension tasks. Van Dyke and McElree (2006) also reported an unusual effect of load (longer reading times in the no-load than in the load unintegrated condition), raising questions about how possible trade-offs between attending to the list and to the sentence might have influenced the results.3

Empirical issues in studies demonstrating syntactic interference effects

As has been noted, Van Dyke and Lewis (2003) found syntactic interference effects in unambiguous sentences. However, these effects were not affected by ambiguity; they were not greater in ambiguous than in unambiguous versions of sentences (8) and (9). We believe that this is an unexpected finding, for the following reasons. In the ambiguous versions of (7)–(9), multiple factors induce the student to be attached as the object of forgot when it is encountered. When was standing is encountered, the student must be detached from forgot and attached as the subject of was standing. Van Dyke and Lewis said that this involves three steps: (1) retrieval of the feature of forgot that allows a sentential complement, (2) deactivation of the NP-complement frame, which makes student available to serve as the subject of was2, and (3) retrieval of the student as the subject of was standing. There should be syntactic interference effects in the retrieval steps (1) and (3), for the following reasons. In step (1), knew in (9) shares allowing a sentential complement with forgot, while waiting in (8) does not. In step (3), the exam creates more interference with the retrieval of a subject in (9) than in (8), as is the case in the unambiguous versions of the sentences. Van Dyke and Lewis described these retrieval processes in the following terms:

when the disambiguating word was[2] occurs, the parser must break the object link between forgot and student in order to attach was[2] into the existing parse tree. In addition, the NP that was the object of forgot must now be reattached as the subject of the IP headed by was[2] and the entire new clause must be attached as the complement of the alternative sentential complement-taking sense of forgot … two retrievals are required: one for the alternative sense of forgot, the assigner of the sentential complement, and one for the subject itself. (p. 287)

The prediction is thus that the syntactic interference effect (longer reading times for was2 in [9] than in [8]) will be greater in the ambiguous than in the unambiguous versions of these sentences. However, this was not the case. Van Dyke and Lewis (2003) concluded that the syntactic interference affects “the process that makes the correct attachment and not those functions related to repairing the incorrect parse” (p. 299). However, since the functions related to repair involve a second retrieval operation, we find these results inconsistent with the model.

Failure to find expected effects of potentially interfering items on retrieval are not restricted to resolution of ambiguities and are not simply null findings (see Phillips, Wagers, & Lau, 2011, for a review). They suggest that some items are not contacted during the retrieval process and, therefore, have implications for retrieval. We return to this issue below.

Empirical issues in studies using the SAT technique

A general issue pertaining to the SAT results is that both asymptotic d′ and dynamics reflect both retrieval and the construction of a syntactic and semantic interpretation, as well as a decision-making process. Equivalent dynamics in different sentence types do not, therefore, necessarily imply equivalent access in retrieval; different combinations of speed of retrieval, computation, and decision making could produce equivalent dynamics. In addition, participants see the same sentence structures many times, possibly promoting the use of particular retrieval strategies, despite the careful selection of stimuli. We will illustrate this second problem with an example.

McElree, Foraker, and Dyer (2003, Experiment 2) studied sentences with relative clauses, shown in (12). (Unacceptable versions of the sentences are indicated by parenthesis and *; the relative clause containing potentially interfering NPs is enclosed in square backets […].)

-

12

The book ripped (/*laughed).

The book [that the editor admired (/*amused)] ripped (/*laughed).

The book [from the prestigious press that the editor admired (/*amused)] ripped (/*laughed).

The book [that the editor who quit the journal admired (/*amused)] ripped (/*laughed).

The book [that the editor who the receptionist married admired] ripped (/*laughed).

The d′ dynamics were the same for sentences (12b), (12c), and (12d), which McElree et al. (2003) took as evidence for a content-addressable retrieval process triggered by a retrieval cue formed by the sentence-final verb. However, there is evidence that participants made judgments about the acceptability of the relative clause incrementally: Correct rejection rates for sentences that became unacceptable at the verb of the relative clause (amused) were at asymptote 50 ms after the end of the sentence (percent correct = 72.3, 76.4, 78.1, 75.3, 75.6, and 80.1 at 50, 300, 500, 800, 1,200, and 3,000 ms) but rose to asymptote over time for sentences that became unacceptable at the verb of the main clause (the sentence-final verb, the retrieval cue–laughed; percent correct = 42.3, 44.5, 63.4, 79.4, 85.1, and 87.7 at 50, 300, 500, 800, 1,200, and 3,000 ms). This indicates that participants made an acceptability judgment about the relative clause when they read the relative clause verb, which would have allowed them to consider only the sentence-initial noun for its plausibility as the subject of the sentence-final verb. In that case, the only item in the memory set at the point of reading the sentence-final verb would have been the sentence-initial NP in (12b), (12c), and (12d), making the d′ dynamics equivalent in those sentences. The repetition of sentences may have been a factor that led to participants making judgments at the relative clause verb.

Other results of this study pertain to the same issue. Rise rates were faster for (12a) and slower for (12e) than for the three other sentences. McElree et al. (2003) attributed the results in (12a) to the immediacy of the NP to the sentence-final verb that served as the retrieval cue, consistent with the results showing that the list-final item, which immediately precedes the retrieval cue, is in a privileged position in cued recall studies of lists. McElree et al. attributed the slowed dynamics in (12e) to computational demands that arise after retrieval has occurred. However, only (12e) did not have a control sentence that became unacceptable at the relative clause verb, so the difference in dynamics for (12e) and the others could have been due to participants considering all NPs in (12e) and not in (12b), (12c), and (12d). Thus, the data from these sentences are consistent with a search process and effects of the task on sentence processing.

Interpretation of results

Despite issues such as those raised above, many results in the studies reviewed in the Mechanisms in ST-WM and Parsing and Interpretation: Empirical Results and Interpretation section and others in the literature demonstrate semantic and syntactic interference effects in online reading times, eye fixations, and SAT asymptotes and are consistent with content-addressable retrieval in many situations. As was noted, these results have generally been taken as providing consistent, converging evidence about the nature of memory processes in parsing and interpretation. There are, however, a number of areas in which there are alternate interpretations of results and others in which the results are hard to reconcile with one another and with other results in the literature.

Number of memory systems needed to account for effects of external load

Fedorenko et al. (2006) argued that an interaction of the semantic similarity of words in recall lists and words in sentences and sentence structure in online processing shows that both sets of words are maintained in a single memory system. However, Henkel and Franklin (1998) found that source memory confusions increased both when items in two contexts were conceptually similar and as the number of similar items in the nonsource list increased. Thus, the effect of match in the high-load condition only in Fedorenko et al. is consistent with separate memory systems for lists and parsing-interpretation, coupled with source memory confusions.

The nature of retrieval

Semantic similarity effects and retrieval

The view that the semantic effects in the articles by Gordon, Fedorenko, and their collaborators are due to interference with retrieval of noun phrases required by the verb of an object-relative clause raises many issues.

First, the semantic similarity effects in these studies cannot be due to the interference-generating mechanism outlined in the Retrieval-Based Parsing section, which maintains that only features that are specified in the retrieval cue affect retrieval. The verb of an object-relative clause may generate a cue to retrieve two noun phrases (and possibly their order), but it cannot generate a cue to retrieve two noun phrases that share a common semantic property or an aspect of form such as being a common or proper noun, because these features of the retrieved items are not present in many sentences. Thus, semantic features of the NPs that are in the memory set are not part of the retrieval cue and cannot give rise to interference by the mechanism outlined above.

In the passage quoted above, Gordon et al. (2001) connected semantic similarity effects to the finding in the ST-WM literature that similarity of items reduces recall of item and order information and did not claim that they were generated by the interference mechanism described in the Retrieval-Based Parsing section. However, suggesting that the semantic effects in these studies are due to the mechanisms that produce similarity effects in the recall of item and order information raises other questions.

One is whether the parser/interpreter makes use of order information; in some models (e.g., Lewis et al., 2006), it does not. Assuming that the parser does use order information, deriving the retrieval mechanism that produced similarity effects in item and order recall in Gordon and his colleagues’ work from mechanisms in ST-WM poses a problem. Two basic mechanisms that could underlie retrieval of order information have been proposed: item-to-item associations (chaining) (Lewandowsky & Murdock, 1989; Wickelgren, 1965, 1966) and an address mechanism (Nairne, 1990a). Address models postulate that items in the recall list are retrieved on the basis of their properties, not on the basis of interitem associations, and negatively affect retrieval only if their features are part of the retrieval cue. Thus, given that semantic features were not part of the retrieval cue in the Gordon and Fedorenko studies, tying their results to models of ST-WM requires that the mechanism for retrieval of order information be some version of chaining. However, chaining models do not appear to be viable. Chaining fails to account for the saw-tooth effect in which similar items are less well remembered in lists of alternating phonologically similar and dissimilar items (Baddeley, 1968, Experiments 5 and 6), the fact that first-in-report errors for dissimilar items (the proportion of errors when responses to all previous items are correct) do not differ in mixed and pure lists (Henson, Page, Norris, & Baddeley, 1996, Experiments 2 and 3), and the fact that relative errors (an erroneous response in the correct position relative to a preceding [necessarily erroneous] response) do not differ between mixed and pure lists (Henson et al., 1996, Experiment 1; see Henson, 1998, for a discussion).

Another concern about attributing semantic interference effects to retrieval is that, if features of items in the memory set that are not part of a retrieval cue interfere with retrieval, other shared properties of items in a sentence that are not part of retrieval cues should affect retrieval. Given the importance of phonological properties in immediate serial recall, which are believed to arise during retrieval, a test case would be phonological similarity of words. The evidence suggests that phonological similarity of words does not affect retrieval at points of syntactic disambiguation (Kennison, 2004) and by the verb of object-relative clauses (Obata, Lewis, Epstein, Bartek, & Boland, 2010; but see Acheson & Macdonald, 2011).

The comparison of the semantic similarity and SAT results also leads to a problem. Similarity of list items does not affect, and may slightly improve, retrieval of item information (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Nairne, 1990b; Nimmo & Roodenrys, 2004; Poirier & Saint-Aubin, 1996; Postman & Keppel, 1977, Experiment 2; Underwood & Ekstrand, 1967; Watkins, Watkins, & Crowder, 1974; Wickelgren, 1965, 1966). Therefore, if semantic similarity effects arise at retrieval, what must be retrieved is item and order information, as Gordon et al. (2001) suggested. However, as was discussed in our review of list memory studies, the content-addressable retrieval suggested by the SAT dynamics results is consistent only with retrieval of item information in ST-WM, not order information (Hockley, 1984, Experiment 3; McElree & Dosher, 1993). Since both the interference and SAT studies involve retrieval of NPs in the same structures (relative clauses), they must be characterizing the same retrieval process. If both sets of results arise during retrieval, the difference between the two studies reflects strategic effects of task or other factors on retrieval mechanisms.

An alternative, suggested by Lewis et al. (2006), is that the semantic similarity effects in the studies by Gordon and his colleagues arose during encoding. One test of an effect of a factor on encoding is whether the effect is increased by a concurrent task (cf. Baddeley, 1968, Experiment 4). Data from some of the studies reviewed above are consistent with this locus of semantic interference. For instance, in Gordon, Hendrick, and Levine (2002), there was an effect of the semantic match of the words in the lists and the sentences in reading times for the sentence-initial segment (but not for the sentence-final segment).

Two points arise if the locus of semantic interference in these studies is at encoding. One is that the results do not bear on retrieval mechanisms. The second is that encoding of words into memory during sentence processing appears to differ from encoding of words in ST-WM, where similarity effects appear to arise during retrieval. Baddeley (1968, Experiment 4) found no effect of presentation in noise on the phonological similarity effect and concluded that the effect did not arise during encoding into ST-WM. Baddeley (1968, Experiments 1–3) also found that the recall of phonologically similar items declined less rapidly that that of phonologically dissimilar items in the Brown–Peterson paradigm, indicating that the phonological similarity effect does not arise during storage. In most models of ST-WM, including feature models in which similarity effects could arise at encoding due to overwriting of features of earlier items (e.g., Neath, 2000), the effect of phonological similarity arises at recall, not encoding. Assuming the principles underlying the effects of phonological and other forms of similarity are the same (which is reasonable in the case of the feature model), if the semantic similarity effects in the studies by Gordon, Fedorenko, and their collaborators arise during encoding, this suggests a difference from the mechanisms found in ST-WM.

Syntactic interference effects and retrieval cues

Syntactic interference effects have been taken as evidence for content-addressable retrieval of items in sentences on the basis of features of retrieval cues created by incoming lexical items and features of their context. However, there is a developing literature that documents the absence of expected effects of potentially interfering items in situations where such effects would be expected if this retrieval mechanism applies.

One phenomenon that has been emphasized is illusions of grammaticality. An example is shown in (13), where the verb agrees with a plural NP that intervenes between it and a singular subject, and many readers initially find the sentence grammatical (Eberhard, Cutting, & Bock, 2005), suggesting that the intervening NP is sometimes retrieved by the agreement features of the verb.

-

*13

The key to the cabinets are on the table.

The critical finding is that illusions of grammaticality are selective. A context that contrasts with subject–verb agreement is a reflexive agreeing with a plural NP that intervenes between it and a singular subject, as in (14), where readers readily report the ungrammaticality (Dillon, Mishler, Sloggett, & Phillips, 2012; cited in Phillips et al., 2011). This argues that the intervening plural NP is not retrieved in (14).

-

*14

The diva that accompanied the harpists on stage presented themselves with lots of fanfare.

Phillips et al. (2011) suggested that the difference between (13) and (14) is due to the nature of the retrieval cues established by the agreement markers on verbs and reflexives. They proposed that reflexives retrieve their antecedents using only structural cues, while verbs create retrieval cues that specify the features of the subject. In their view, this difference is due to the fact that a sentence subject reliably predicts a verb and its agreement features, whereas a reflexive cannot be reliably predicted.

Items in certain syntactic positions appear not to be contacted during the retrieval process even when the retrieval cue specifies their features. For instance, NPs in certain positions do not appear to be contacted when a verb of an object-relative clause retrieves its object. Traxler and Pickering (1996) found evidence for a retrieval cue that specified semantic features of the object of the verb of a relative clause (similar to Van Dyke & McElree, 2006, discussed above) in (15) in the form of longer reading times for shot in the anomalous version of that sentence (with the NP garage), but no prolongation of reading times for wrote in the version of (16) with the NP city:

-

15

That’s the pistol/garage with which the heartless killer shot the hapless man.

-

16

We liked the book/city that the author who wrote unceasingly saw while waiting for a contract.

This suggests that the city/book are not in the list of items contacted by the retrieval cue established by wrote in (16). It been suggested that this is because of the syntactic environment in which the city/book and wrote occur–that the book/city is outside a syntactic “island” that contains wrote.

One common feature of sentences that might serve to restrict the items contacted by a retrieval cue is placing one or more items in linguistic focus. Further consideration of the results in McElree et al. (2003) suggests that this may be the case. Recall that McElree et al. found that SAT dynamics differed for (12e) and (12b–d), repeated here:

-

12

-

b

The book that the editor admired ripped.

-

c

The book from the prestigious press that the editor admired ripped.

-

d)

The book that the editor who quit the journal admired ripped.

-

e)

The book that the editor who the receptionist married admired ripped.

-

b

In other studies, structures comparable to (12e) did not show different dynamics from others tested. There were no differences in d′ dynamics in (17a–17c) (McElree, 2000) or in (18a–18c) (McElree et al., 2003):

-

17

It was the book that the editor enjoyed.

It was the book that the editor who the secretary married enjoyed.

It was the book that the editor who the secretary who quit married enjoyed.

-

18

It was the book that the editor enjoyed.

It was the book that the secretary believed the editor enjoyed.

It was the book that the secretary believed that the journalist reported that the editor enjoyed.

The clefted noun phrase in (17) and (18) is in linguistic focus, which could exclude the other nouns in those sentences from being contacted by the retrieval cue.

The selectivity of syntactic interference effects and grammaticality illusions point to highly detailed features of retrieval cues. Even with highly detailed cues, formulating retrieval cues in such a way that items in “invisible” environments are not contacted by a content-addressable retrieval mechanism has proven challenging. Alcocer & Phillips (unpublished manuscript) described several ways in which retrieval cues could include complex relations of syntactic nodes, such as those needed to account for the possible antecedents of reflexives (“c-command”; Reinhart, 1976). Although it is possible to formulate such cues, they suggested that the memory demands of maintaining the types of annotated syntactic structures that such cues require are too great to be realistic. They advocate hybrid retrieval processes that include both content-addressable retrieval and search mechanisms:

We might conclude that it is attractive to invoke a serial mechanism for accessing memory that explicitly uses the graph structure of a tree to access c-commanding nodes. Such mechanisms capture relational notions such as c-command with far greater ease than do mechanisms that implement parallel access. (ms. pp. 35–36)

On this view, there are two types of retrieval operations in parsing and interpretation: content-addressable retrieval and search. Within the set of search mechanisms, searches that use different retrieval cues would be expected to search a structure held in memory in different ways. Phillips et al. (2011) summarized the picture in the following terms:

We find many situations where on-line language processing is highly sensitive to detailed grammatical constraints and immune to interference from inappropriate material…. Yet in many other situations we find that on-line processes are susceptible to interference and to grammatical illusions. In order to explain this ‘selective fallibility’ profile we have argued that speakers build richly structured representations as they process a sentence, but that they have different ways of navigating these representations to form linguistic dependencies. The representations can be navigated using either structural information or using structure-insensitive retrieval cues. (p. 173)

The role of capacity and temporal limits in parsing and interpretation and their relation to ST-WM

As has been discussed, Lewis (1996) suggested that a capacity limit derived from ST-WM applies in parsing and interpretation. His proposal raises a variety of issues.

One is the number of items of the same type that the buffer can contain. Lewis (1996) set the limit of two on the number, on the grounds that two is the minimum number of items that must be connected in a relation, and it would be of interest to explore the possibility that it is also the maximum number that can be connected in a relation. However, this number does not correspond to any suggestion about the size of a fixed-capacity, capacity-limited portion of ST-WM, which, as we have seen, has been estimated as one by McElree and four to five by Cowan. It would be possible to set the number of items that can be maintained in a flexible-capacity ST-WM store such as that proposed by Verhaeghen to two, but to do so only to relate the capacity limit of a parsing store to one in ST-WM is obviously circular.

In other work, Lewis and his colleagues have proposed a second link between capacity limits in ST-WM and parsing and interpretation—namely, that the structure of their model, with three buffers (a control buffer, a problem state buffer, and a retrieval buffer), “has much in common with conceptions of working memory and short-term memory that posit an extremely limited focus of attention of one to three items, with retrieval processes required to bring items into focus for processing” (Lewis & Vasishth, 2005, p. 380). However, the existence of three buffers differs from the ST-WM concept of a single CS and triples the capacity limit of the CS.

Both these suggestions regarding ways that putative capacity limits on parsing and interpretation might be derived from capacity limits in some part of ST-WM raise broader issues.

One pertains to the nature of items in stores utilized in parsing and interpretation. In Lewis’s model, what is stored in the control and problem state buffers are phrase markers that are formed as the sentence is processed. As was noted above, these representations are created by a left-corner parser that expands the phrase marker associated with each new word according to stored procedures (rules). The contents of these phrase markers must remain accessible. In Fig. 1, the word the triggers the creation of an NP, a VP, and a dominating S node. If the next word is the adjective big, as in the phrase the big dog, it must be attached within the NP that is formed after the word the is encountered. Thus, in the terminology used to characterize the CS, the items in these buffers are chunks (Cowan, 2000; Halford, Cowan, & Andrews, 2007; Miller, 1956; Verhaeghen et al., 2004) that are not “opaque” (Halford et al., 2007).

The accessibility of the elements in a chunk in Lewis’s model differs sharply from the conceptualization of chunks in the ST-WM literature. Halford et al. (2007) made an analogy between chunks and the representation of speed as a point on a line, as in a car dashboard display; the constituents of the concept of speed (distance/time) cannot be accessed from such a representation. The inability to access the contents of a chunk increases memory capacity (in some sense) at the expense of computational capacity. The distance that would be traveled in a given time cannot be calculated from the position of a needle on a car dashboard, but requires access to the constituent concepts. In Lewis’s model, storage demands of memory are reduced because what is stored is a chunk, but the computational capacity of the system is not affected because the contents of the chunk are available. These are not the properties that have been attributed to a capacity-limited CS.

In addition, the transparency of chunks in Lewis’s model differs from applications of models of capacity limits of the CS to other cognitive phenomena. For instance, Halford et al. (2007) argued that the limits of the CS restrict human reasoning to problems with relational complexity (“arity”) of no more than four, but their model requires that the reasoning process cannot access items within a chunk. If the capacity limits in processing in various domains are to be explained because of capacity limits in the CS, the characterization of how chunks are processed must apply universally.4

A second issue is that capacity limits and content-addressable retrieval apply to different stores in models of ST-WM—capacity limits, if they exist, to the CS or an expanded focus of attention, and content-addressable retrieval to items outside the capacity-limited portion of ST-WM (i.e., to items in LTM). If capacity limits exist in parsing and interpretation, this would require that they are due to items being stored in a store from which they are not retrieved by a content-addressable mechanism, a noticeable discrepancy across the models we have been discussing.

A more general issue that arises regarding capacity limitations is whether there are any such limitations in ST-WM. As was reviewed above, in their work on memory, McElree and his colleagues have argued that there are no items in memory that are in an activated but unattended state and that the number of items that can be maintained in focal attention in memory is limited to one. This model does not contain a capacity-limited store. Consistent with this model, McElree and his colleagues have argued that the SAT dynamics for retrieval are the same in sentences as in LTM, which is not capacity limited. As was noted, if this model of retrieval is correct, there are no storage capacity limits on parsing and interpretation. McElree (personal communication) has suggested that phenomena sometimes attributed to capacity limits are due to interference.

A second feature of Lewis’s model is its reliance on a second limitation of ST-WM—temporal decay. Both locality and antilocality effects are attributed to how representations decay and are reactivated by retrieval processes (Vasishth & Lewis, 2006). However, evidence for temporal decay in ST-WM is controversial (Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2008).

In summary, the effort to attribute parsing complexity to capacity (or temporal) limitations of ST-WM encounters a variety of challenges, some related to the details of the proposed limitations in parsing and interpretation and those that have been proposed in some models of ST-WM, some related to the nature of the items maintained in memory in parsing and interpretation, and some related to inconsistencies with proposals about the relation of retrieval dynamics in parsing and interpretation to various ST-WM and in stores.

Overlap and nonoverlap of retrieval mechanisms in ST-WM and in retrieval-based parsing

The lines of research reviewed in the Mechanisms in ST-WM and Parsing and Interpretation: Empirical Results and Interpretation section relate many mechanisms derived from the study of ST-WM to memory in parsing and interpretation: capacity limitations, content-addressable retrieval, retrieval of item and order information, temporal decay of representations, and so forth. In fact, the set of mechanisms attributed to ST-WM that have been appealed to in this literature is greater than our review has indicated. For instance, Johnson, Lowder, and Gordon (2011) suggested that encoding of item versus order information in sentences was affected by the nature of noun phrases in sentences and related their results to the attention-based mechanism postulated in the “the item-order theory of list composition effects” (McDaniel & Bugg, 2008). The invocation of a large number of mechanisms derived from models of ST-WM in models of memory utilized by parsing and interpretation leads to two questions: Are all the mechanisms that have been suggested to apply in parsing/interpretation reasonably well established in the ST-WM literature? Are there mechanisms that are reasonably well established in the ST-WM literature that are not used in parsing and interpretation?

The answer to the first question is almost certainly “no.” We noted above that chaining models, needed to account for semantic interference effects if they arise during retrieval, and decay in ST-WM have little support as features of ST-WM. The answer to the second question seems to be “yes.” Many mechanisms postulated to support memory functions in ST-WM, such as Weber-compressed temporal intervals from retrieved item to retrieval cue or response (Brown, Neath, & Chater, 2007), positional activation gradients measured from both list-initial and list-terminal items (Henson, 1998), temporal oscillators that estimate list length (Brown, Preece, & Hulme, 2000; Henson & Burgess, 1997), and others (for a review, see Henson, 1998), are not plausible candidates for mechanisms that support the memory requirements of parsing and interpretation.

This has consequences for the relation of memory in parsing and interpretation to ST-WM. If mechanisms such as temporal decay or chaining are found in parsing and interpretation and not in ST-WM, they are either specific to parsing and interpretation or derived from memory systems other than ST-WM. If there are mechanisms found in ST-WM and not in parsing and interpretation, parsing and interpretation, at most, select from memory mechanisms found in ST-WM.

The mechanisms listed above that are postulated to apply in ST-WM and that are not plausible candidates for mechanisms underlying memory in parsing and interpretation have been postulated in models of recall, not recognition. One might therefore consider whether parsing and interpretation use only mechanisms that support recognition. This has not been the assumption of researchers in this field, who have invoked mechanisms that apply in either recognition or recall. Uniform SAT dynamics have been found in recognition; they cannot be examined in recall. As has been noted, effects of phonological and semantic similarity occur in immediate serial recall Baddeley (1966), but not item recognition (Wickelgren, 1965). However, it might be possible to restrict consideration of mechanisms to those found in only one task.