Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this secondary data analysis was to compare event-free survival among four groups of patients with heart failure (HF) that were stratified by presence of depressive symptoms and antidepressants.

Methods

We analyzed data from 209 outpatients (30.6% female, 62 ± 12 years, 54% NYHA Class III/IV) enrolled in a multicenter HF registry who had data on depressive symptoms, antidepressant use, and cardiac rehospitalization and death outcomes during 1 year follow up. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Results

Depressive symptoms, not antidepressant therapy, predicted event-free survival (HR=2.4, 95% CI = 1.2–4.6, p =.009). Depressed patients without antidepressants had 4.1 times higher risk of death and hospitalization than non-depressed patients on antidepressant (95% CI = 1.2–13.9, p=.022) after controlling for age, gender, NYHA class, body mass index, diabetes, medication of ACEI and beta blockers.

Conclusion

Antidepressant use was not a predictor of event-free survival outcomes when patients still reported depressive symptoms. Ongoing assessment of patients on antidepressants is needed to assure adequate treatment.

Introduction

Depressive symptoms are very common among patients with heart failure (HF),1 and are a known risk factor for hospitalization and death.1–4 In a landmark meta-analysis, Rutledge et al., reported that overall, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with HF ranges from 9% to 60%, and on average, one out of every five patients (21.5%) experiences depressive symptoms.1 The prevalence of major depression ranges between 14% to 26% in patients with HF.2, 5, 6 Both major depression and the presence of depressive symptoms are associated with declining functional status and worsening quality of life in patients with HF.1, 2, 4 Furthermore, the presence of depressive symptoms is independently associated with increased risk of frequent hospitalization and death.2–4 HF Patients with depressive symptoms have a 3-fold increased risk of hospitalization and 2-fold increased risk of death at 1 year follow up compared to those without depressive symptoms.1 Increasing evidence suggests that screening and treatment of depressive symptoms is an essential component in the management of HF,7 but pharmacological treatment rates for depression in patients with HF are not well known.

Prescription of antidepressants has become increasingly common for treatment of depression and is often used as a first line of treatment. The safety of using antidepressants and their effectiveness in treating depressive symptoms in patients with HF have been reported.8–13 Categories of antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and miscellaneous antidepressants. SSRIs are currently considered the most favorable choice for depression treatment of HF patients. SSRIs have negligible effects on cardiac conduction and ECG intervals, but patients who are taking multiple drugs should use caution due to the possibility of drug interaction. TCAs are relatively safe in patients with HF for short-term treatment of depression, but they have multiple serious adverse effects, particularly in the elderly. Miscellaneous antidepressants include second-generation antidepressants such as trazodone and bupropion. These antidepressants have not been studied extensively in patients with HF. Buproprion has been suggested as an option; however, there is limited evidence to support its use and it should be used with caution in patients with hypertension. Trazodone is known to have a sedative effect.

The effects of antidepressants on hospitalization and death outcomes in this population are controversial.14–16 Tousoulis15 found that antidepressant use improved survival when treatment was combined with a beta-blocker in 250 patients with end-stage severe HF. On the other hand, O’Connor14 reported that antidepressant use increased the risk of mortality outcomes in hospitalized HF patients (N=1006) but antidepressant use did not predict increased risk of mortality when depression levels were controlled. Furthermore, in a randomized controlled trial of depressed patients with HF (N =469), O’Connor and colleagues found that sertraline treatment did not improve short and long-term morbidity and mortality when compared to placebo.10

Although researchers have reported that failing to improve depressive symptoms using antidepressants increased the risk of mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction,17, 18,16 it is still unclear whether antidepressant use improves hospitalization and death in community-dwelling patients with HF. Knowing that depressive symptoms increase the risk of hospitalization and death, we were interested in whether antidepressant use influenced the association of depressive symptoms with hospitalization and death outcomes in outpatients. Therefore, the purposes of this secondary data analysis were (1) to determine whether depressive symptoms and antidepressant use independently predicted event-free survival (defined as cardiovascular-related hospitalization and all-cause death in outpatients with HF); and 2) to compare event-free survival among four groups that were stratified with regard to depressive symptoms and antidepressant use (i.e., no depressive symptoms without antidepressants, no depressive symptoms with antidepressants, depressive symptoms without antidepressants, and depressive symptoms with antidepressants).

Methods

Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the HF Quality of Life (QOL) registry. The QOL registry is a collaborative effort among investigators at 8 academic medical centers. A detailed summary of registry methods has been previously published.19, 20 Several reports from the QOL registry have examined the relationship between depressive symptoms on cardiac event-free survival.21–23,22 However, in these prior manuscripts, researchers did not evaluate the effects of antidepressant use on cardiac outcomes. This secondary data analysis is unique in that it examines the relationship between depressive symptoms, antidepressant use, and cardiac event-free survival.

Three studies in the HF QOL registry were simultaneously conducted by researchers from the Research and Intervention for Cardiopulmonary Health Heart Program at the College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, and each study collected the desired data for this secondary data analysis. Detailed of these three studies have been reported elsewhere,22 but are summarized here for relevance to the current investigation. The first study tested the effects of biofeedback and cognitive therapy on HF outcomes. The second study was an observational, longitudinal study focused on exploring possible mechanisms for the relationship between depressive symptoms and poor outcomes in patients with HF. The third study examined the associations among nutritional intake, inflammation, and outcomes in patients with HF. 22

Although each study had unique primary specific aims, all study participants were outpatients in clinics in Kentucky recruited using the same inclusion criteria. Eligible patients were those who met the following criteria: 1) physician-confirmed diagnosis of preserved or non-preserved systolic function HF; 2) no acute myocardial infarction in the previous 3 months; 3) not referred for heart transplantation; 4) no terminal illness that would be expected to cause death within the next 12 months; or 5) no valvular or peripartum etiology for HF. A total of 345 patients were enrolled at the data analysis time. For this secondary data analysis, we included 209 unique patients who had not received any intervention and who had data on depressive symptoms, antidepressant use, and hospitalization/death outcomes during the one year follow-up.

Measures

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a valid and reliable instrument for the measurement of depressive symptoms.24, 25 The PHQ-9 has been used to predict quality of life and mortality in HF.23, 26 The PHQ-9 has 9 items that reflect the criteria for diagnosis of clinical depression from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV. All items are rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) and the total score can range from 0 to 27. Higher total scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms during the past 2 weeks. Patients who score above 9 are considered to have moderate to severe depressive symptoms. The cut point of 9 was reported to have 88% sensitivity and 88% specificity for diagnosing major depression.24 Previous researchers have reported the internal reliability of the PHQ-9 with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging between .82 to .89.24, 27 The Cronbach’s alpha was .85 in this study.

Antidepressants

Antidepressant use was determined during the initial assessment. Patients were asked to bring all of their current medication bottles to the appointment. Medications were also confirmed by review of medical charts at the initial assessment. The antidepressants used by study participants included SSRIs, TCAs, and miscellaneous antidepressants such as selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI).

Event-free Survival

The outcome variable in this study was one-year cardiac event-free survival, defined as time to a combined end-point of hospital admission for cardiovascular reasons or death from all causes during the first year of follow-up. The protocol for event coding was developed by investigators prior to subject enrollment in the original studies. A cardiovascular hospitalization was defined as an unanticipated admission for the following reasons: HF exacerbation, shortness of breath, cardiovascular-related chest pain, myocardial infarction, syncope, dysrhythmias (including internal cardiac defibrillator [ICD] firing), ICD or biventricular pacemaker placement due to worsening HF, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and palpitations. As part of the original study protocols, participants received monthly telephone calls for one year to identify hospitalization events. The phone logs were examined and events were coded by a co-author who was blinded to the baseline assessment. Event coding was examined independently by two additional co-authors, who were also blinded to baseline assessment. Any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved by a meeting of the 3 co-authors in order to come to a final coding decision. All hospitalizations were verified with hospital records; dates and causes of death were determined by hospital records, family interview, and death certificates.

The dates and reasons for admission and death were collected by monthly phone call follow up and by reviewing electronic hospital and medical records. Death certificates were obtained to confirm cause of death.

Other Variables of Interest

Demographic data (i.e., age, gender, race, education, and marital status) and clinical characteristics (i.e., New York Heart Association [NYHA] class, etiology, comorbidities, medications, left ventricular ejection fraction, and body mass index) were collected to describe sample characteristics and control for possible confounding factors. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (cm2).

Protocols

The institutional review board approved the individual studies and all patients provided informed, signed consent. After completion of each study, data were de-identified and integrated into the HF QOL registry database at the first author’s institution. The institutional review board approved secondary data analysis with this de-identified dataset as an exempt protocol.

Trained research nurses screened and recruited eligible patients during outpatient clinic visits or via phone calls. After eligible patients provided written informed consent, the baseline assessment was completed. Medical records were reviewed to confirm comorbidities and medications. For safety reasons, suicidality was assessed using item 9 from the Beck Depression Inventory-II. If a patient chose the option “I would like to kill myself” or “I would kill myself if I had the chance,” they would have been referred immediately to a psychiatric nurse practitioner. There were no instances of suicidality that occurred during the original studies.

Data analysis

To accomplish specific aim 1, patients were divided into two groups based on presence of depressive symptoms. Based on the standard cut-point for the PHQ-9, those with depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 > 9) were placed in one group and those without depressive symptoms (PHQ ≤ 9) were placed in a second group.24 Patients were also divided into two groups based on antidepressant use. Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics between groups. To accomplish specific aim 2, Patients were further grouped into four groups according to their depressive symptoms and whether or not they were on antidepressants: 1) no depressive symptoms without antidepressants, 2) no depressive symptoms with antidepressants, 3) depressive symptoms without antidepressants, and 4) depressive symptoms with antidepressants. One-way analysis of variance and chi-square tests were used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics among the four groups.

For both specific aims, cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare event-free survival for cardiovascular-related hospitalization and all-cause death and obtain hazard ratios among the groups in two steps. We first conducted unadjusted analyses, and then adjusted analyses controlling for age, gender, NYHA class, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors use, and beta-blocker use. Data analyses in this study were performed using SPSS version 17, with alpha set at .05. It is not appropriate nor is it statistically valid to conduct a post-hoc power analysis and estimate power for this secondary data analysis.28

Results

Sample characteristics

Depressive symptoms

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The mean of the PHQ-9 was 5.7 (SD = 5.4). Of the entire sample, 45 patients (21.5%) had depressive symptoms (PHQ score > 9). Patients with depressive symptoms were 6 years younger (mean age 57.6 ±9.8 vs. 63.0 ±12, p<.05), had fewer years of education (high school or less 67% vs. 33%, p = .012), and were more likely to have severe functional decline (NYHA class III or IV: 76% vs. 48%, p = .001) compared with patients without depressive symptoms. There was no differences in gender, marital status, ejection fraction, etiology, or body mass index between two groups. Of patients with depressive symptoms, 35.6% of patients were on antidepressants while 64.4% were not on antidepressants (p = .029).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with heart failure (N = 209)

| Characteristics | M ± SD / n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.9 ± 11.7 |

| Female gender | 64 (30.6%) |

| Caucasian | 176 (84.2%) |

| Married | 121 (57.9%) |

| Ischemic etiology for heart failure | 113 (54.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 90 (44.3%) |

| Hypertension | 153 (73.2%) |

| Ejection fraction, % | 34.3 ± 14.0 |

| NYHA Class I | 12 (5.7%) |

| Class II | 85 (40.7%) |

| Class III | 87 (41.6 %) |

| Class IV | 25 (12.0%) |

| ACEI | 156 (74.6%) |

| ARB | 23 (11.0%) |

| Beta-Blocker | 186 (89.0%) |

| Diuretics | 155 (74.2%) |

| ICD | 89 (42.6%) |

| Body mass index | 31.8 ± 7.6 |

| Death (%) | 6 (2.9%) |

| Cardiac hospitalization | 37 (17.7%) |

MI = Myocardial Infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; ACEI = Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB = Angiotensin II receptor Blockers; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Antidepressant use

Of the 209 patients, 48 patients (23%) were on antidepressants at baseline. The use of antidepressants is listed on Table 2. Patients on antidepressants were more likely to be female (46% vs. 26%; p = .012) than patients who were not on antidepressants. There were no differences in age, gender, marital status, education, comorbidity of diabetes mellitus, ejection fraction, body mass index, and etiology between two groups. Of patients who were on antidepressants, 67% had no depressive symptoms while 33% had depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Use of antidepressants (N=48)

| Antidepressant | Example of Generic name | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | Sertraline, Fluvoxamime | 23 (48%) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant (TCAs) | Doxepin, Amitriptyline | 3 (6.3%) |

| Selective norepinephrien reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs) | Duloxetine | 4 (8.3%) |

| Other (noradrenergic/specific serotonergic, antidepressant norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, tetracyclic antidepressant) |

Mitrazapine, Bupropion, Trazodone |

11 (22.9%) |

| Combination (SSRIs + TCAs; SSRIs + Other; TCAs+ Others; SNRI + TCAs) |

7 (14.5%) |

Comparison of groups stratified by antidepressants use and depressive symptoms

As shown in Table 2, 63% of subjects did not have depressive symptoms and were not on antidepressant; 15.3% did not have depressive symptoms but were on antidepressants; 13.9% had depressive symptoms but were not on antidepressant; and 7.6% had depressive symptoms and were on antidepressants. Patients who had depressive symptoms but were not on antidepressants were younger (mean age = 58, p =.025), more likely to have not graduated high from school (69%; p = .004), and more likely to have worse functional status (NYHA class III/IV, 79.3%, p=.008) than those in the other three groups. The patients who had depressive symptoms and were on antidepressants reported the highest level of depressive symptoms among the groups (PHQ-9 mean = 15.5, p < .001). Otherwise, the four groups had similar demographic (i.e., ethnicity, marital status) and clinical characteristics (i.e., comorbidity of diabetes and hypertension, ACE inhibitor, beta blocker, left ventricular ejection fraction, and body mass index).

Hospitalization and death

During the one year follow up period, 68 patients were admitted to the hospital and 6 patients died. Of the 68 hospitalizations, 37 were related to worsening symptoms of HF or another cardiovascular diagnosis and 31 hospitalizations for non-cardiac reasons.

Event-free survival for Specific Aim 1

Table 4 shows the results of an unadjusted Cox proportional hazard regression of predictors for event-free survival. Depressive symptoms were an independent predictor of shorter event-free survival. Patients with depressive symptoms had more than double the risk of cardiac hospitalization or death compared to patients without depressive symptoms (HR = 2.401; 95% CI =1.247 – 4.623, p = .009) without controlling for covariates. However, antidepressant use was not a significant predictor of event-free survival of cardiac hospitalization or death without controlling for covariates (HR = .765, 95% CI, 0.355–1.649, p = .49). There was no difference in the risk of cardiac hospitalization or death between patients who were and were not on antidepressants.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard regression for event-free survival without controlling for covariates (N=209)

| Predictor | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | 2.401 | 1.247 – 4.623 | .009 |

| Prescribed antidepressants | .765 | .355–1.649 | .494 |

| Absence depressive symptoms with prescribed antidepressant (referent group) | 1.0 | - | - |

| Absence depressive symptoms without prescribed antidepressant | 1.708 | .596 –4.895 | .319 |

| Presence of depressive symptom with prescribed antidepressant | 3.270 | .816 – 13.110 | .094 |

| Presence of depressive symptom without prescribed antidepressant | 4.012 | 1.232 – 13.069 | .020 |

Event-free survival for Specific Aim 2

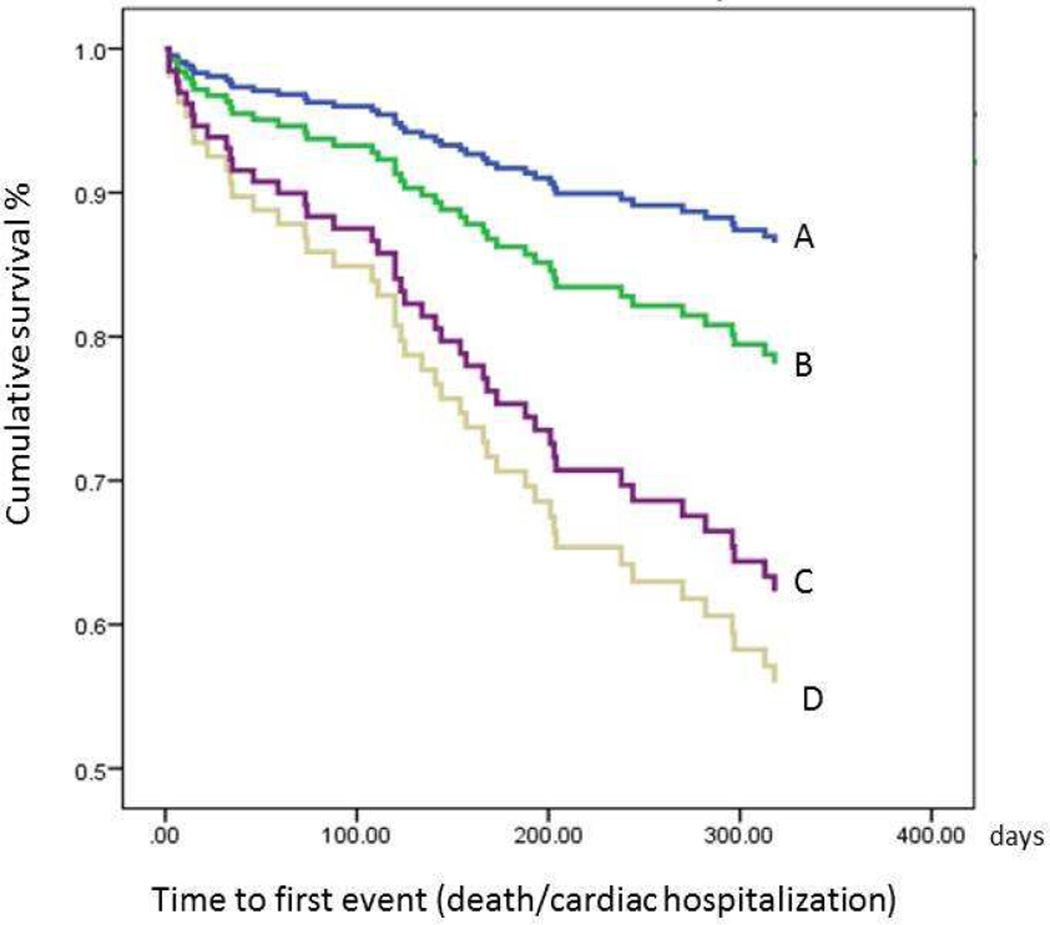

Unadjusted survival curves for the four groups that were stratified by depressive symptoms and antidepressant (Figure 1) showed that non-depressed patients who were on antidepressants had the longest event-free survival while patients who were on antidepressants and reported depressive symptoms had the shortest event-free survival. Regardless of antidepressant use, the two depressed groups experienced comparable event-free survival (Table 4) but, only non-depressed groups without antidepressants groups experienced significantly shorter event-free survival in unadjusted cox proportional hazard regression.

Figure 1.

Event-free survival for patients who were stratified by depressive symptoms and use of antidepressants (N = 209)

Legend:

A=Absence of depressive symptoms with prescribed antidepressants;

B= Absence of depressive symptoms without prescribed antidepressants;

C= Presence of depressive symptoms without prescribed antidepressants;

D=Presence of depressive symptoms with prescribed antidepressants

As shown in Table 5, when we controlled for age, gender, NYHA, body mass index, ACE inhibitor use, beta-blocker use and diabetes, depressed patients who were not on antidepressants had a 4.13 times higher risk of cardiac events (95% CI: 1.23 – 13.89; p = .022) compared to non-depressed patients who were on antidepressants. Depressed patients who were on antidepressants had a 4 times higher risk of cardiac events compared to non-depressed patients who were on antidepressants but there was non-significant trend (p = .061).

Table 5.

Cox regression model predicting cardiac event-free survival after controlling for all covariates (N=209)

| Step /predictors | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | .996 | .967– 1.025 | .76 |

| Gender, Female (male: referent) | .816 | .388 – 1.713 | .64 | |

| NYHA class (I/II) (referent) | 1.0 | – | – | |

| III | 1.350 | .697 – 2.61 | .390 | |

| IV | .858 | .268 – 2.745 | .863 | |

| Body mass index | .942 | .893 – .992 | .019 | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, Yes | .790 | .270 – 1.5721 | .480 | |

| Beta-Blockers, Yes | .682 | .270 – 1.719 | .412 | |

| Diabetes | 1.014 | .532–1.935 | .965 | |

| 2 | Absence depressive symptoms with prescribed antidepressant (referent group) | 1.0 | .025 | |

| Absence depressive symptoms without prescribed antidepressant | 1.363 | .464 – 4.003 | .573 | |

| Presence of depressive symptom with prescribed antidepressant | 4.036 | .940 – 17.321 | .061 | |

| Presence of depressive symptom without prescribed antidepressant | 4.129 | 1.227 – 13.89 | .022 | |

Note: CI = Confidence Interval; NYHA = New York Heart Association

Discussion

The most compelling finding in our study was that patients who were prescribed antidepressants but still reported high levels of depressive symptoms had the highest risk of hospitalization or death compared to the other groups. Antidepressant use by itself was not associated with the risk of cardiac hospitalization or death in patients with HF. Our findings are consistent with those of O’Connor et al.,14 who found that antidepressant use did not impact morbidity and mortality in patients with HF. In contrast, our results did not support other researchers’ findings that antidepressants had beneficial or harmful effects on mortality in patients with HF.14, 15

A significant proportion of patients in our study had high levels of depressive symptoms even though they were taking antidepressants. There are several potential reasons for this finding.21 First, these patients could have treatment-resistant depression—defined as a failure to respond to the standard dose of antidepressants after a minimum of 6 weeks of continuous treatment.29 Treatment-resistant depression is clinically significant because it may lead to a higher risk of mortality. In a large randomized controlled trial of patients with acute myocardial infarction, patients whose depressive symptoms did not respond to antidepressant treatment had a higher risk of late mortality (> 6 months after acute myocardial infarction).17 Patients whose depressive symptoms failed to improve substantially during the treatment with either sertraline or placebo had a 2.39-folder of high risk of death during 7 years of follow up.18

Another potential reason that patients had depressive symptoms despite antidepressant therapy may be non-adherence. Depressed patients with HF often do not follow critical treatment regimens (i.e., HF medications, diet and exercise),30, 31 which may contribute to their poor outcomes.32 Non-adherence to antidepressants may prevent maximum efficacy of the therapy and contribute to persistent depressive symptoms. Finally, some patients may have depressive symptoms despite antidepressant therapy because of inadequate dosage treatment and/or follow-up. The clinical implications of this are that clinicians need to reassess and reevaluate depressive symptoms once patients are started on antidepressants. Ongoing assessment of patients who are taking antidepressants is needed to assure adequate treatment, and clinicians may consider alternate treatment choices if monotherapy does not improve depressive symptoms. Many non-pharmacological strategies including cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, and psychosocial intervention may also be effective in improving depressive symptoms in patients with HF.33–35

In our study, a significant percentage (61.5%) of patients who had high levels of depressive symptoms were not taking antidepressants. The risk of hospitalization and death for these patients was similar to those who had depressive symptoms and were taking antidepressants. This group may represent patients with HF who have undetected or untreated depressive symptoms. Few researchers have reported the rate of undetected or untreated depressive symptoms in patients with HF. 36 Turvey et al reported that 18% of elderly patients with HF experienced mild or major depression (as measured with the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), and that 40% of depressed patients were not taking antidepressants.36

We observed that many patients with advanced HF (NYHA Class III or IV) had depressive symptoms regardless of antidepressant use; 75% of patients with depressive symptoms who were taking antidepressants and 81% of patients with depressive symptoms who were not taking antidepressants had advanced HF. One potential reason that we found such a high rate of untreated or undetected depressive symptoms may be the symptom overlap between depression and advanced HF. For example, symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, loss of energy, and sleep disturbances are found both in depression and advanced HF.37 Patients and health care providers may perceive somatic/affective symptoms of depression as a normal feature of advanced HF. Importantly, researchers have found that patients with HF who have higher levels of somatic/affective symptoms are less likely to remit from depression than those with cognitive/affective symptoms.38

Another potential reason that we had so many patients with untreated depressive symptoms may be that healthcare providers are uncomfortable or reluctant to prescribe antidepressants because of potential adverse effects (i.e., hypotension, alteration in cardiac conduction) and drug interactions.39 Antidepressant therapy may not be acceptable to many patients with HF who have depressive symptoms. According to Holzapefel, out of 320 German HF outpatients with depressive symptoms (as assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9), only 33% accepted psychotherapeutic and/or pharmacologic treatment. Nineteen percent refused the treatment because they did not want to discuss their emotional distress or did not feel the need for any treatment, and 29% refused treatment but said they would consider treatment if their emotional distress worsened. Although routine screening for depression/ depressive symptoms in coronary heart disease has been suggested by the American Heart Association practice guidelines7, health care providers face challenges in increasing the acceptability of treatment option for patients.

This study has several limitations. First, adherence to antidepressant use was not objectively measured. Thus, we cannot guarantee that patients were actually taking antidepressants. However, in order to reduce measurement error, all medications—including prescribed antidepressants—were confirmed by chart review and by looking at medication bottles that patients brought to their baseline appointment for the original studies. Second, we do not have data on the history of depression, nature of depression treatment, duration of antidepressant use, and use of alternative non-pharmacological therapies (i.e. cognitive behavioral therapy) for depressive symptoms. Third, we were unable to examine the association between type of antidepressants and outcomes because of the small number of participants who were taking antidepressants. Although the sample size in this study was somewhat small (N = 209) it was large enough to detect differences in event-free survival between groups. Finally, the average age of our participants was relatively young (61±12 years), which may limit generalizability to older HF populations.

Based on our findings, we believe that prospective studies are needed to examine whether previous episodes of depression, length of antidepressant treatment, changes to treatment, and use of other therapies for depressive symptoms affect health outcomes of patients with HF. Further studies are also needed to determine whether adherence to prescribed antidepressants predicts HF outcomes. The clinical implications of our study are that once antidepressant treatment is initiated, healthcare providers should monitor the patient’s depressive symptom level and adjust antidepressant dosages appropriately. Clinicians should recognize that patients with undetected or untreated depressive symptoms—as well as those with under-treated depressive symptoms—are at higher risk for cardiovascular events.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that depressive symptoms—not antidepressant use—independently predicted death and cardiac hospitalization in outpatients with HF. Taking antidepressants did not alter the relationship between depressive symptoms and poor outcomes in this study. Specifically, antidepressant use did not improve outcomes and in fact was associated with worse outcomes in outpatients who still reported depressive symptoms. Our results also suggest that clinicians should monitor depressive symptoms in patients with HF who are taking antidepressants in order to assure adequate treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether screening for depressive symptoms and providing effective treatment for depressive symptoms can improve outcomes of patients with HF.

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristics among patients stratified by depressive symptoms and use of antidepressants (N=209)

| Absence of depressive symptoms | Presence of depressive symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No antidepressants |

Yes antidepressants |

No Antidepressant |

Yes antidepressant |

p-value* |

| n = 132 (63%) | n=32 (15.3%) | n =29 (13.9%) | n =16 (7.6%) | ||

| Age, years (M ± SD) | 63.6 ± 11.9 | 60.7 ± 12.2 | 58.0 ± 10.26 | 56.9 ± 9.2 | .025 |

| Female, gender (%) | 25.0 | 40.6 | 31.0 | 56.2 | .038 |

| Education ≤ High school (%) | 63.5% | 25.0 | 69.0 | 62.5 | .004 |

| Ethnicity, white (%) | 87.1 | 78.1 | 81.2 | 79.3 | .757 |

| Married (%) | 62.9 | 50.0 | 44.8% | 56.2% | .239 |

| Depressive symptoms (M ± SD)a | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 4.0 ± 2.8 | 13.9 ± 2.5 | 15.5 ± 3.7 | <.001 |

| DM (%) | 43.2 | 40.6 | 34.5 | 66.7 | .266 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.1 | 81.2 | 82.8 | 71.4 | .517 |

| ACEI (%) | 76.5 | 75.0 | 65.5 | 75.0 | .677 |

| Beta-blocker (%) | 88.5 | 87.5 | 89.7 | 100 | .547 |

| Ejection Fraction, % (M ± SD) | 34.2 ± 13.9 | 34.6 ± 13.1 | 33.7 ± 14.7 | 36.9 ± 15.7 | .974 |

| NYHA Class III/IV (%) | 48.5 | 43.8 | 79.3 | 68.8 | .008 |

| Body mass index | 31.1 ± 7.5 | 33.0 ± 9.5 | 32.9 ± 6.0 | 33.8 ± 5.7 | .297 |

| Ischemic etiology | 60.3% | 37.5% | 53.6% | 43.8 | .091 |

P-value for one-way ANOVA or chi-square test among 4 groups;

PHQ-9 score

Methods.

Study design

This study was a secondary data analysis that used combined data collected from three prospective, longitudinal studies conducted between 2002 and 2009 by the Research and Intervention for Cardiopulmonary Health (RICH) Heart research collaborative at the College of Nursing, University of Kentucky. The details of the three studies have been described previously.18 Patients with HF were recruited from outpatient clinics in Kentucky

Protocols

Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Kentucky was obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, Blazing MA, Davenport C, Califf RM, Krishnan RR, O'Connor CM. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Archives of Iinternal Medicine. 2001;161:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Trivedi R, Johnson KS, O'Connor CM, Adams KF, Jr, Dupree CS, Waugh RA, Bensimhon DR, Gaulden L, Christenson RH, Koch GG, Hinderliter AL. Relationship of depression to death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:367–373. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Krone RJ, Smith LJ, Rich MW, Eisenkramer G, Fischer KC. Psychological factors in silent myocardial ischemia. Psychosomatic medicine. 1991;53:13–24. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig HG. Depression in hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20:29–43. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lesperance F, Mark DB, Sheps DS, Taylor CB, Froelicher ES. Depression and coronary heart disease: Recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: A science advisory from the american heart association prevention committee of the council on cardiovascular nursing, council on clinical cardiology, council on epidemiology and prevention, and interdisciplinary council on quality of care and outcomes research: Endorsed by the american psychiatric association. 2008;118:1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glassman AH, Bigger JT, Gaffney M, Shapiro PA, Swenson JR. Onset of major depression associated with acute coronary syndromes: Relationship of onset, major depressive disorder history, and episode severity to sertraline benefit. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:283–288. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr, Krishnan KR, van Zyl LT, Swenson JR, Finkel MS, Landau C, Shapiro PA, Pepine CJ, Mardekian J, Harrison WM, Barton D, McLvor M. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute mi or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Silva SG, Cuffe MS, Callwood DD, Zakhary B, Stough WG, Arias RM, Rivelli SK, Krishnan R Investigators S-C. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: Results of the sadhart-chf (sertraline against depression and heart disease in chronic heart failure) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb SS, Kop WJ, Thomas SA, Katzen S, Vesely MR, Greenberg N, Marshall J, Cines M, Minshall S. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of controlled-release paroxetine on depression and quality of life in chronic heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2007;153:868–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Laliberte MA, White M, Lafontaine S, Calderone A, Talajic M, Rouleau JL. An open-label study of nefazodone treatment of major depression in patients with congestive heart failure. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48:695–701. doi: 10.1177/070674370304801009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artinian NT, Artinian CG, Saunders MM. Identifying and treating depression in patients with heart failure. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19:S47–S56. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200411001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Mehta RH, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, Califf RM, Krishnan RR. Antidepressant use depression, and survival in patients with heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168:2232–2237. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tousoulis D, Antoniades C, Drolias A, Stefanadi E, Marinou K, Vasiliadou C, Tsioufis C, Toutouzas K, Latsios G, Stefanadis C. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors modify the effect of beta-blockers on long-term survival of patients with end-stage heart failure and major depression. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2008;14:456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summers KM, Martin KE, Watson K. Impact and clinical management of depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:304–322. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: The enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease patients (enrichd) randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glassman AH, Bigger JT, Jr, Gaffney M. Psychiatric characteristics associated with long-term mortality among 361 patients having an acute coronary syndrome and major depression: Seven-year follow-up of sadhart participants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1022–1029. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riegel B, Moser DK, Glaser D, Carlson B, Deaton C, Armola R, Sethares K, Shively M, Evangelista L, Albert N. The minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire: Sensitivity to differences and responsiveness to intervention intensity in a clinical population. Nursing Research. 2002;51:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riegel B, Moser DK, Rayens MK, Carlson B, Pressler SJ, Shively M, Albert NM, Armola RR, Evangelista L, Westlake C, Sethares K Collaborat HFT. Ethnic differences in quality of life in persons with heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2008;14:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KS, Lennie TA, Heo S, Moser DK. Association of physical versus affective depressive symptoms with cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Psychosom Meicine. 2012;74:452–458. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824a0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung ML, Lennie TA, Dekker RL, Wu JR, Moser DK. Depressive symptoms and poor social support have a synergistic effect on event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2011;40:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song EK, Moser DK, Frazier SK, Heo S, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Depressive symptoms affect the relationship of n-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide to cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardic Failure. 2010;16:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The phq-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of prime-md: The phq primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faller H, Stork S, Schowalter M, Steinbuchel T, Wollner V, Ertl G, Angermann CE. Depression and survival in chronic heart failure: Does gender play a role? Eur J Heart Fail. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Perkins SM, Gradus-Pizlo I, Kareken D, Kim J, Ding Y, Sauve MJ, Sloan R. Measuring depressive symptoms in heart failure: Validity and reliability of the patient health questionnaire-8. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:146–152. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: The pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat. 2001;55:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rieckmann N, Gerin W, Kronish IM, Burg MM, Chaplin WF, Kong G, Lesperance F, Davidson KW. Course of depressive symptoms and medication adherence after acute coronary syndromes: An electronic medication monitoring study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:2218–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rieckmann N, Kronish IM, Haas D, Gerin W, Chaplin WF, Burg MM, Vorchheimer D, Davidson KW. Persistent depressive symptoms lower aspirin adherence after acute coronary syndromes. American Heart Journal. 2006;152:922–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronish IM, Rieckmann N, Halm EA, Shimbo D, Vorchheimer D, Haas DC, Davidson KW. Persistent depression affects adherence to secondary prevention behaviors after acute coronary syndromes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1178–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Higgins MK, Musselman DL, Smith AL. Combined exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy improves outcomes in patients with heart failure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostis JB, Rosen RC, Cosgrove NM, Shindler DM, Wilson AC. Nonpharmacologic therapy improves functional and emotional status in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1994;106:996–1001. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan MJ, Wood L, Terry J, Brantley J, Charles A, McGee V, Johnson D, Krucoff MW, Rosenberg B, Bosworth HB, Adams K, Cuffe MS. The support, education, and research in chronic heart failure study (search): A mindfulness-based psychoeducational intervention improves depression and clinical symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. American Heart Journal. 2009;157:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turvey CL, Klein DM, Pies CJ. Depression, physical impairment, and treatment of depression in chronic heart failure. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21:178–185. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guck TP, Elsasser GN, Kavan MG, Barone EJ. Depression and congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2003;9:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2003.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang W, Krishnan R, Kuchibhatla M, Cuffe MS, Martsberger C, Arias RM, O'Connor CM. Characteristics of depression remission and its relation with cardiovascular outcome among patients with chronic heart failure (from the sadhart-chf study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2011;107:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glassman AH, Johnson LL, Giardina EG, Walsh BT, Roose SP, Cooper TB, Bigger JT., Jr The use of imipramine in depressed patients with congestive heart failure. JAMA. 1983;250:1997–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]