Abstract

Centrosomes, the principal microtubule-organizing centers of animal somatic cells, consist of two centrioles embedded in the pericentriolar material (PCM). Pericentrin is a large PCM protein that is required for normal PCM assembly. Mutations in PCNT cause primordial dwarfism. Pericentrin has also been implicated in the control of DNA damage responses. To test how pericentrin is involved in cell cycle control after genotoxic stress, we disrupted the Pcnt locus in chicken DT40 cells. Pericentrin-deficient cells proceeded through mitosis more slowly, with a high level of monopolar spindles, and were more sensitive to spindle poisons than controls. Centriole structures appeared normal by light and electron microscopy, but the PCM did not recruit γ-tubulin efficiently. Cell cycle delays after ionizing radiation (IR) treatment were normal in pericentrin-deficient cells. However, pericentrin disruption in Mcph1−/− cells abrogated centrosome hyperamplification after IR. We conclude that pericentrin controls genomic stability by both ensuring appropriate mitotic spindle activity and centrosome regulation.

Keywords: pericentrin, centrosome, DNA damage response, mitosis, checkpoint

Introduction

The large coiled-coil protein, pericentrin/kendrin, is a conserved component of the periocentriolar material (PCM) of animal centrosomes.1-4 Pericentrin acts as scaffold within the PCM and interacts with a number of partners, in particular γ-tubulin and other members of the γ-tubulin ring complex, providing a structural framework in which the MTOC activities can occur5-7 (reviewed in ref. 8). Assembly of pericentrin at centrosomes requires the microtubule motor, cytoplasmic dynein, with which it interacts in the organization of the mitotic spindle.9,10

Overexpression of pericentrin causes centrosome abnormalities and disrupts mitotic spindle integrity, possibly through its sequestration of dynein.9,11 However, such overexpression also facilitates the de novo centriole duplication process, which exists in addition to the standard templated mechanism by which centrioles normally duplicate.12,13 Pericentrin overexpression caused expansion of the PCM, allowing the formation of multiple daughter centrioles independently of any spatial or numerical control from the mother centrioles.14 This observation prompted the hypothesis that the mother centriole’s principal role in centriole assembly is the regulation and specification of a PCM scaffold, rather than the provision of a template.14

Loss-of-function analyses of pericentrin have demonstrated roles for the protein in controlling centrosome functions during both mitosis and interphase. Injection of anti-pericentrin antibodies disrupted mitotic spindle formation in frog embryos.1 Knockdown or expression of dominant-negative pericentrin caused a p53-p21-dependent delay at G1 phase in telomerase-immortalized human RPE1 cells, as well as centriole splitting.15 A similar cell cycle delay was also seen after Pcnt knockdown in primary human fibroblasts.16 In transformed human cells, Pcnt knockdown disrupted mitotic spindle formation and γ-tubulin, Cep192 and Cep215 recruitment to the centrosome, although no effect on microtubules was observed in interphase cells.7,17,18 Recent findings have indicated that pericentrin cleavage by separase is required for the mitotic centriole disengagement that allows reduplication, although how its removal controls licensing is not yet established.19,20 In Drosophila, P-element-mediated disruption of the gene encoding the pericentrin ortholog, D-PLP, led to reduced centrosomal accumulation of γ-tubulin and of other centrosome components, although no marked impact on mitosis was observed.4 Notably, ciliary abnormalities arose in the d-plp mutant flies, a phenotype reflected in the recent description of defective olfactory cilia formation in mice with a gene trap insertion in the 5′ untranslated region of the first exon of Pcnt.21 Together, these data clearly implicate pericentrin in regulatory and signaling functions of the centrosome.

Loss-of-function mutations in PCNT have been described in microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type II (MOPD II; MIM 210720), a rare condition that is characterized by extremely short stature and microcephaly, but without marked mental retardation.22 PCNT mutations have also been described in SCKL patients,23 although the clinical features of PCNT-SCKL patients could fit with an MOPD II diagnosis.24 Importantly, cells from PCNT-SCKL patients also show defective DNA damage responses.23 One key cell cycle-regulatory step that occurs at the centrosome is the activation of Cdk1-cyclin B at the onset of mitosis.25 It has been reported that centrosomal Chk1 regulates this activation through its inhibition of the Cdk1-activating Cdc25B phosphatase.26-28 In this model, centrosomal Chk1 localization is regulated by pericentrin, with pericentrin being controlled by Mcph1/BRIT1 (hereafter Mcph1), a centrosomal and nuclear protein that also plays a part in the DNA damage response.29 However, an alternative model has also been advanced, in which a nuclear Chk1 signal restrains Cdk1 activation, with a different kinase activating the centrosomal Cdk1.30,31

We wished to test the functions of pericentrin in cell cycle responses to genotoxic stress. Here, we report the generation of Pcnt mutants in the genetically tractable chicken DT40 model. These cells do not show the lethal p53-p21 response seen in non-transformed cells, so are suitable for this analysis. Pericentrin-deficient cells are viable, with mitotic defects and sensitivity to spindle poisons. Notably, loss of pericentrin suppressed the centrosome hyperamplification phenotype that we see in Mcph1-deficient cells,32 supporting the idea that the PCM contributes to genome integrity through checkpoint regulation, as well as through ensuring accurate mitosis.

Results

Gene targeting of Pcnt

We set out to explore pericentrin’s role in genome stability using reverse genetics in the hyper-recombinogenic chicken DT40 cell line. Pericentrin was originally identified in mouse as a 220 kDa protein, with further analysis of this gene predicting a 250 kDa protein.1,33 A human ortholog of the gene encoding pericentrin was described as encoding a larger than 350 kDa protein, dubbed kendrin/pericentrin-B, containing an extended C-terminal region with homology to calmodulin-binding domains.2,3 Pericentrin-A, the shorter form, and kendrin/pericentrin-B arise from alternative splicing of the same transcript,33 and an additional transcript that encodes an N-terminally deleted isoform, denoted pericentrin-S, was identified from Northern analysis of different mouse tissues.34

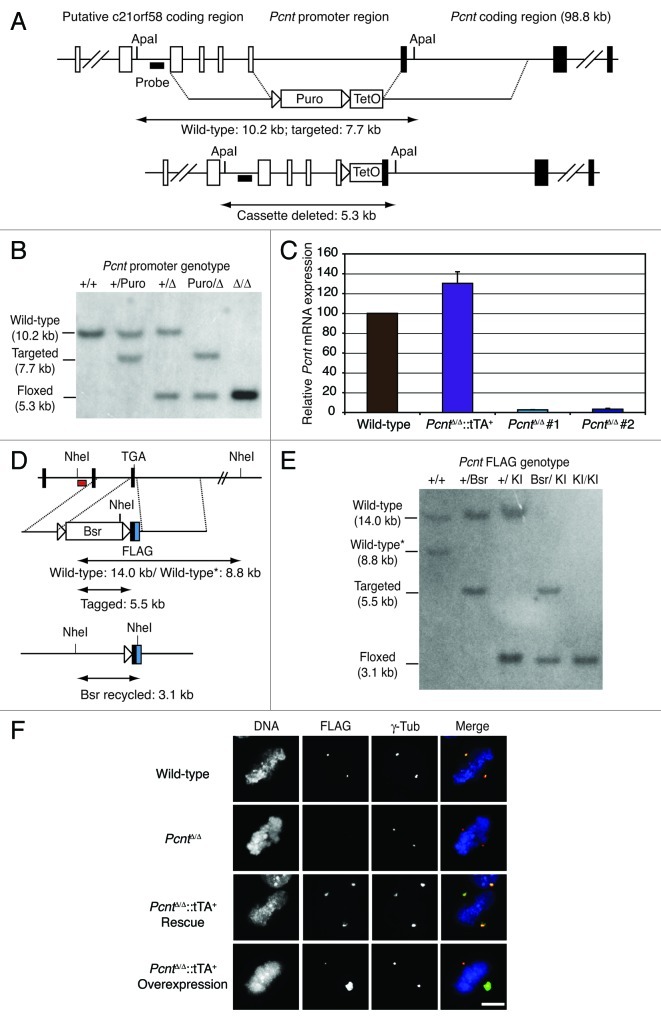

Given the complexities of gene expression from the pericentrin (Pcnt) locus, we employed a promoter-hijack strategy to disrupt Pcnt and to ablate pericentrin expression.35 As shown in Figure 1A, this involved the replacement of 5.5 kb upstream of the Pcnt coding sequence, which we presumed to contain the principal Pcnt promoter sequence, with a Tet operator array, using gene targeting and subsequent Cre recombinase deletion of the selectable cassette. Successful targeting of this sequence and cassette excision were verified by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B) and two targeted, recombined clones were used for further analysis (PcntΔ/Δ #1 and #2). As previously published work had suggested that pericentrin might be essential in cell lines, we transfected Pcnt heterozygote cells with a plasmid that encoded the tet transactivator (tTA) under the control of the Kif4A promoter, pKif4A-tTA2,35 prior to targeting of the remaining Pcnt allele. While PcntΔ/Δ cells showed 2% of wild-type Pcnt expression, the Kif4A promoter-driven tTA led to various levels of Pcnt expression in PcntΔ/Δ clones, as determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). We defined a clone that expressed 130% of the wild-type level of Pcnt as a “rescue” and a clone that expressed 900X of the control message as an overexpressor. To confirm that pericentrin protein expression was ablated by gene targeting, we used gene targeting to introduce a FLAG tag into the 3′ end of the chicken Pcnt locus (Fig. 1D). After Southern blot analysis to confirm this knock-in (Fig. 1E), we used immunofluorescence microscopy to test whether pericentrin was detectable after gene targeting. As shown in Figure 1F, no pericentrin was detectable in PcntΔ/Δ cells, although the rescue and overexpressor clones showed wild-type levels and very large aggregates of pericentrin at their centrosomes, respectively. These data confirm that our promoter hijack of Pcnt abrogated pericentrin expression in DT40 cells.

Figure 1. Disruption of Pcnt by promoter targeting. (A) Diagram of the chicken Pcnt locus and the targeting vector designed to replace the promoter region with a TetO cassette. Puro, puromycin resistance cassette. (B) Southern blot showing targeted integration of the promoter hijack construct and the Cre-mediated excision of the resistance cassette from the two alleles of Pcnt. (C) Histogram showing the expression of Pcnt normalized to β-actin in cells of the indicated genotype. (D) Diagram of the 3′ end of the Pcnt locus showing the vector designed to add a FLAG-tag to the end of the gene. Bsr, blasticidin resistance cassette. (E) Southern blot showing targeted integration of the FLAG-tag construct and Cre-mediated excision of the resistance cassette from the two alleles of Pcnt. Note that there is a polymorphic difference between the two wild-type Pcnt alleles that is detected with this digest; the lower allele (*) is the first one targeted. KI, knock-in. (F) Immunofluorescence micrograph of Pcnt-FLAG knock-in DT40 cells of the indicated Pcnt promoter genotype stained with antibodies to FLAG (green) and γ-tubulin (red). Cells were counter-stained with DAPI to visualize the DNA (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm.

Mitotic delay and spindle abnormalities in pericentrin-deficient cells

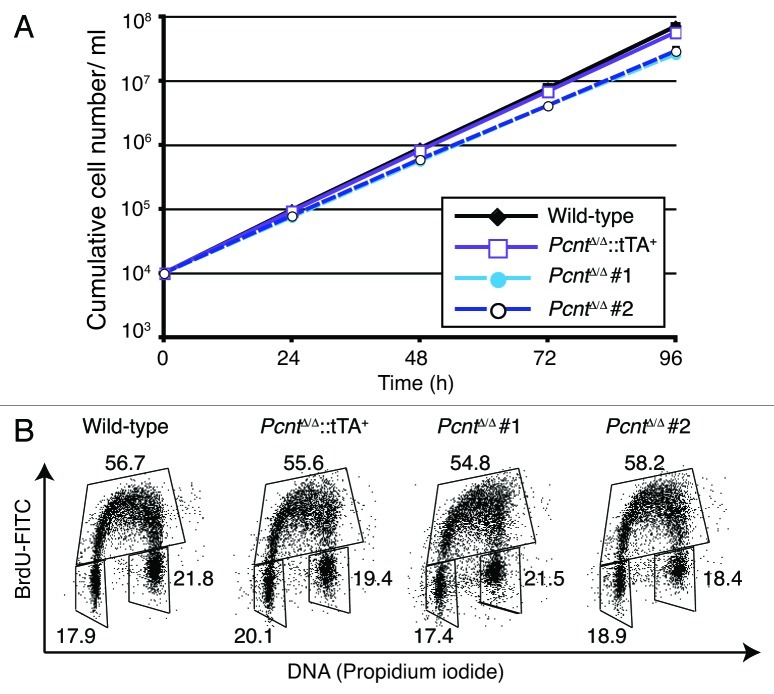

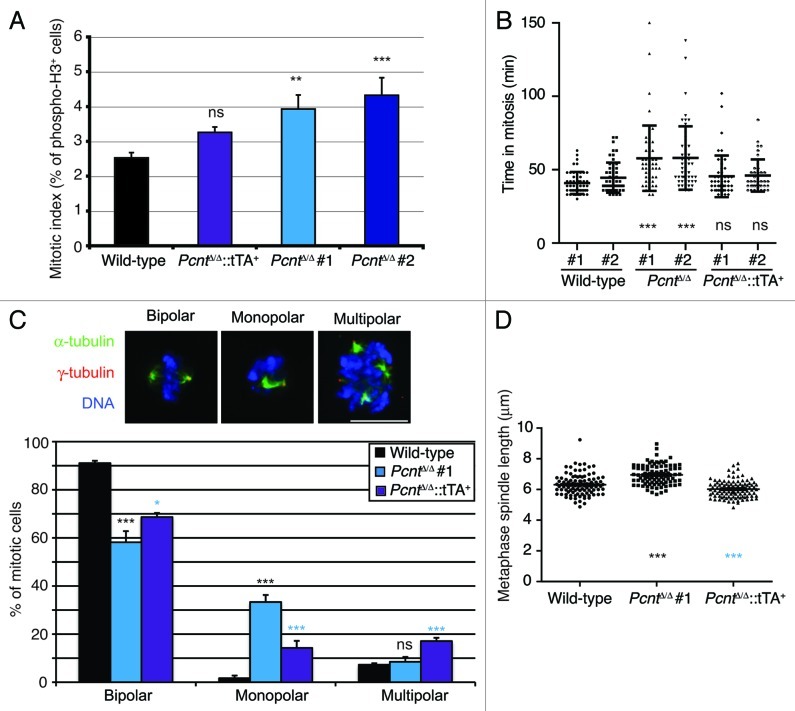

Despite the loss of pericentrin, PcntΔ/Δ cells were viable. While they proliferated more slowly than wild-type or rescued cells (Fig. 2A), the overall proportions of their cell cycle were similar to controls (Fig. 2B). Importantly, this was due to an increase in the fraction of cells in mitosis (Fig. 3A), suggesting a delay in progression through M. As our rescued cell line proliferated at wild-type rates and showed close to a wild-type mitotic index, the impact on cell proliferation was clearly due to pericentrin deficiency. We next performed live-cell microscopy to determine whether the increased mitotic index was due to such a mitotic delay. Histone H2B-RFP was stably transfected into wild-type and PcntΔ/Δ cells as a marker to allow visualization of chromosome dynamics. Time-course microscopy revealed that PcntΔ/Δ cells took longer to complete mitosis, with the mean time taken from chromosome condensation to decondensation being 40.9 ± 7.5 min and 44.6 ± 10.3 min in two wild-type cell lines and 57.8 ± 22.3 min and 58.0 ± 21.6 min in two PcntΔ/Δ cell lines (Fig. 3B). Monitoring the completion of prometaphase, we found that 25.0% of PcntΔ/Δ cells (n = 140) took > 60 min to achieve chromosome alignment and enter anaphase, compared with only 2.6% of wild-type cells (n = 116) and 11.1% of cells in the rescue (n = 108), suggesting a defect in prometaphase chromosome alignment. As shown in Figure 3C, we also saw an increase in the proportion of monopolar mitotic spindles, which was a notable phenotype observed in experiments where PCNT was depleted by siRNA in HeLa cells.7,18 This phenotype was partially rescued by the re-expression of pericentrin, although we also observed an increase in multipolar spindles in the rescued cells, suggesting that there might be some residual problems in spindle formation when Pcnt levels are not the same as in wild-type cells. Furthermore, 54.7 ± 7.9% of the bipolar spindles in PcntΔ/Δ cells were abnormal as against 9.4 ± 4.5% in wild-type cells, with the pole-pole axis not being perpendicular to the metaphase plate, for example. Metaphase spindle lengths were increased in bipolar PcntΔ/Δ cells to 6.95 ± 0.65 µm (n = 103) from 6.31 ± 0.68 µm (n = 93) in wild-type DT40 cells (Fig. 3D). Together, these data indicate significant difficulties in mitotic spindle organization resulting from the absence of pericentrin.

Figure 2. Pericentrin deficiency causes proliferative delay. (A) Proliferation analysis of cells of the indicated genotype. Data points show mean ± s.d. of the results from at least three separate experiments. Doubling times were 7.52 ± 0.34 h and 7.86 ± 0.40 h for wild-type and rescue cells; 8.91 ± 0.58 h and 8.54 ± 0.51 h for two Pcnt-deficient cell lines. (B) FACS plot of cell cycle distributions in asynchronous cells of the indicated genotype. The G1 (lower left), S (top) and G2/M gates are boxed and the numbers refer to the percentage of cells detected in each of the gates.

Figure 3. Pericentrin deficiency causes mitotic delay and spindle defects. (A) Histogram showing mitotic indices in cells of the indicated genotype, as determined by flow cytometry of phospho-histone H3. Data are the mean ± s.d. of three separate experiments. (B) Duration of mitosis in pericentrin-deficient cells. Cells of the indicated genotype were stably transfected with histone H2B-RFP and then imaged by time-lapse microscopy. Mitotic duration was defined as the time taken from chromosome condensation to decondensation. Data show mean ± s.d. for at least 50 individual cells analyzed as data points. (C) Analysis of mitotic abnormalities in the absence of pericentrin. Micrographs show our classification of mitotics in Pcnt-deficient DT40 cells stained with antibodies to α- (green) and γ-tubulin (red). DNA was visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. Histogram shows the analysis of mitotics in cell lines of the indicated genotype with each data point representing the mean + s.d. of 3 experiments in which 100 cells were scored. (D) Pole-pole spindle lengths in metaphase in cells of the indicated genotype. Only cells with chromosomes aligned at a metaphase plate were analyzed. At least 90 cells were quantitated per genotype. Statistical significances shown in black were compared with wild-type; those in light blue were in comparison with Pcnt-deficient cells. NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

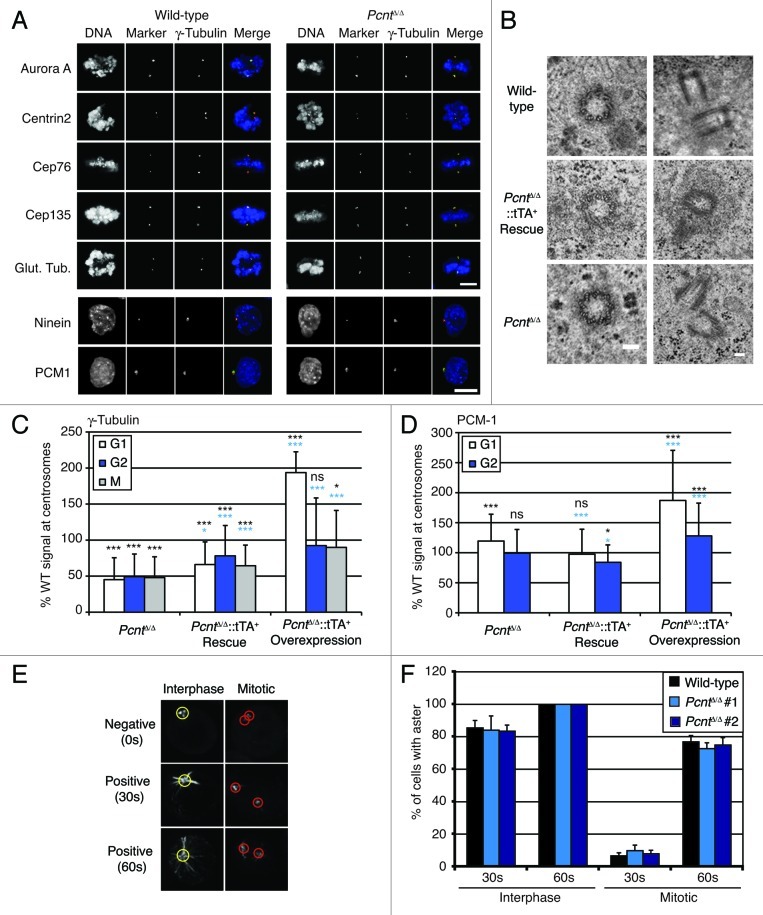

We next assessed the impact of pericentrin deficiency on the centrosome. We saw no impact of pericentrin deficiency on centrosome composition, as determined by fluorescence microscopy using antibodies specific for the centrosome-associated kinase, Aurora A and the centriole components, centrin2, Cep135, glutamylated tubulin, Ninein and Cep76 (Fig. 4A). To confirm these observations at higher resolution, we performed electron microscopy. As shown in Figure 4B, the centrioles in pericentrin-deficient cells were orthogonally connected and composed of nine triplet microtubules, with mean diameters of 216.8 ± 9.6 nm (n = 11) in wild-type cells and 212.5 ± 8.7 nm (n = 6) in PcntΔ/Δ cells, showing no impact of pericentrin deficiency on the characteristic ultrastructure of the centriole. While we observed electron-dense PCM surrounding the centriole in wild-type and PcntΔ/Δ cells, we were not able to determine whether there was any difference in this assembly in the absence of pericentrin.

Figure 4.Pcnt-deficient cells have apparently normal centriolar structures but reduced centrosomal γ-tubulin. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of wild-type and Pcnt-deficient DT40 cells stained with antibodies to the indicated centrosome component (green) and γ-tubulin (red). DNA was visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Transmission electron micrographs of centrosomes in cells of the indicated genotype. Top panel shows individual centrioles and lower panel, pairs. Scale bars, 100 nm. (C) Histogram showing the centrosomal levels of γ-tubulin in cells of the indicated genotype at the indicated cell cycle stage, as determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Histogram shows the mean + s.d. from the analysis of at least 100 cells in three separate experiments, normalized to wild-type. (D) Histogram showing the centrosomal levels of PCM-1 in cells of the indicated genotype at the indicated cell cycle stage, determined as for (C). Statistical significances shown in black were compared with wild-type; those in light blue were in comparison with Pcnt-deficient cells. NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. (E) Microscopy analysis of microtubule nucleation in DT40 cells before and after release from arrest in nocodazole at 4°C. Cells were stained with antibodies to α-tubulin. An aster was defined as an α-tubulin structure of 2.5 µm (yellow circles) or 2 µm (red circles) diameter in interphase or mitotic cells, respectively. (F) Robust aster formation in the absence of pericentrin. Histogram shows the mean + s.d. of three separate experiments in which at least 50 centrosomes were analyzed.

Given the interaction of pericentrin with γ-tubulin,5,7 an obvious possibility for how pericentrin deficiency might affect the mitotic spindle lay in an effect on centrosomal γ-tubulin. We used quantitative fluorescence microscopy to assess how much γ-tubulin lay at centrosomes in pericentrin-deficient cells. As shown in Figure 4C, centrosomal γ-tubulin was reduced in a pericentrin-dependent manner at all stages in the cell cycle. The rescue of pericentrin expression did not restore centrosomal γ-tubulin entirely to wild-type levels, although there were significant increases compared with the knockout cells. This is consistent with the partial rescue of the monopolarity phenotype that we describe in Figure 3. Centrosomal γ-tubulin levels increased notably in G1 cells when pericentrin was overexpressed, consistent with previous reports.14 However, centrosomal levels of PCM-1, another pericentrin interactor, but one that is not directly involved in centrosome organization,3,17 were less affected by pericentrin deficiency, increasing in G1 phase but not in G2 (Fig. 4D). Together, these findings support the role ascribed to pericentrin in centrosomal γ-tubulin localization and thus in PCM organization.7

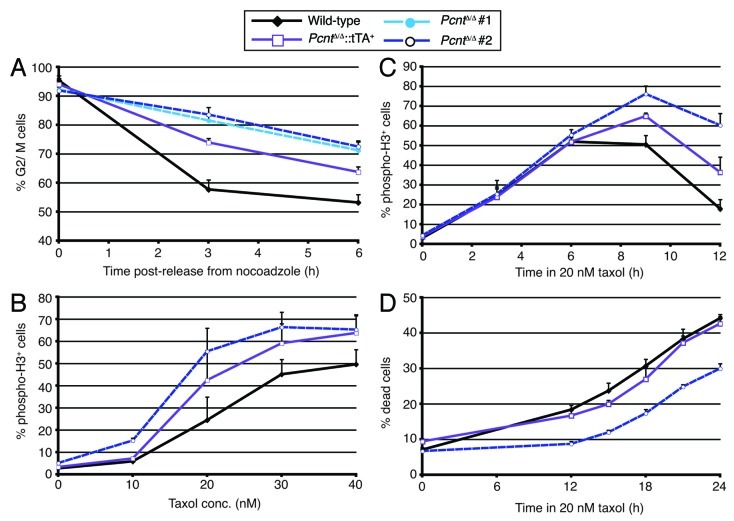

Exploring how pericentrin deficiency might have an impact on the spindle, we saw no impact of pericentrin loss on the ability of cells to nucleate microtubule asters after combined nocodazole and cold depolymerizaton of microtubules (Fig. 4E and F). Assessment of microtubule signals by immunofluorescence microscopy intensity, rather than by quantitation of the cells with a given aster diameter, also showed no difference between wild-type and pericentrin-deficient cells. This observation was unexpected, with the decline in centrosome γ-tubulin. A possibility is that the reduced γ-tubulin at centrosomes is nevertheless sufficient for the microtubule nucleation that we can quantitate. Although our analysis of microtubule nucleation revealed no impact of pericentrin deficiency, this assay might not be sufficiently sensitive to detect a difference in MTOC functions. Therefore, we analyzed cellular responses to spindle poisons at the level of the cell cycle. Figure 5A shows that pericentrin-deficient cells are notably slower than wild-type cells at completing mitosis after release from a nocodazole-induced arrest, with the re-expression of pericentrin partly alleviating this effect. In low doses of taxol, fewer wild-type than PcntΔ/Δ cells were arrested in mitosis after 12 h treatment (Fig. 5B), and subsequent analysis showed that wild-type cells were quicker than PcntΔ/Δ cells to satisfy the spindle assembly checkpoint and leave mitosis (Fig. 5C). This had the effect of retarding the lethality induced by 20 nM taxol treatment in pericentrin-deficient cells (Fig. 5D). These data show that the loss of pericentrin impairs the cellular responses to spindle disruption, possibly through the requirement for pericentrin for a fully functional PCM.

Figure 5.Pcnt-deficient cells show delayed satisfaction of the spindle assembly checkpoint. All graphs show datapoints which are the mean + s.d. of three experiments in which 10,000 events were scored. (A) Exit from nocodazole-induced mitotic delay after drug washout in cells of the indicated genotype, as determined by flow cytometric analysis of DNA content. No increase in sub-G1 fraction was seen in these analyses. (B) Dose-dependence of mitotic arrest imposed by increasing doses of taxol. Mitotic indices were determined by flow cytometry for phospho-histone H3 after 12 h incubation with the indicated taxol concentrations. (C) Taxol-induced arrest and satisfaction of this checkpoint in cells of the indicated genotype, as determined by flow cytometric analyses of phospho-histone H3 over time. No increase in sub-G1 fraction was seen in these analyses. (D) Cell death induced by low-dose taxol treatment in cells of the indicated genotype, as determined by flow cytometry for Annexin V and DNA content. Dead cells were counted as all those with AnnexinVhi signal.

Genetic interactions between Pcnt and Mcph1

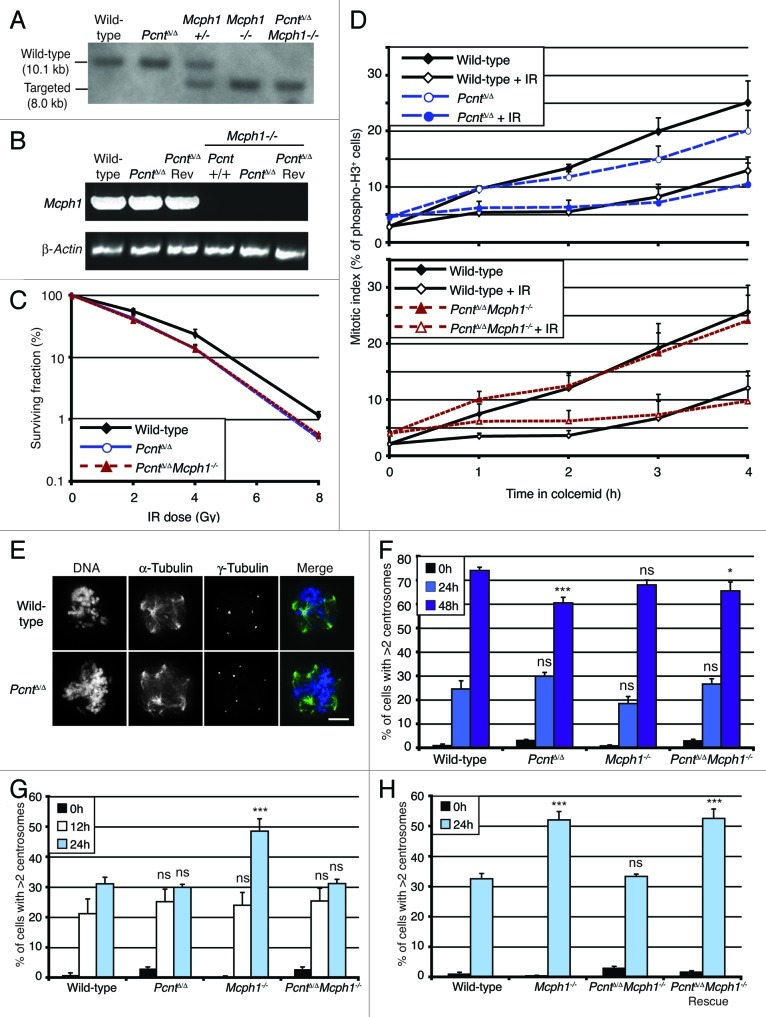

We next examined the role of pericentrin in the DNA damage response.23,29 Current models suggest that pericentrin interacts with Mcph1 and thus affects Chk1 signaling to Cdk1.29,36 To explore this idea, we tested the genetic interactions between Pcnt and Mcph1 by targeting Mcph1 in our PcntΔ/Δ cells using a previously published strategy.32 Southern blot analysis confirmed this targeting (Fig. 6A) and RT-PCR was used to show that Mpch1 expression was abrogated in the double mutant cells (Fig. 6B). In terms of the DNA damage response, PcntΔ/Δ cells were only slightly more sensitive than wild-type controls to ionizing radiation (IR), and PcntΔ/Δ Mcph1−/− showed similar levels of radiosensitivity to the single mutants (Fig. 6C; ref. 32). As shown in Figure 6D, we observed an intact G2-to-M checkpoint response to IR in both PcntΔ/Δ and PcntΔ/Δ Mcph1−/− DT40 cells.

Figure 6. Pericentrin deficiency rescues DNA damage-dependent centrosome hyperamplification in Mcph1-deficient cells. (A) Southern analysis of targeting of the Mcph1 locus in DT40 cells, using the previously published targeting strategy.32 (B) RT-PCR confirmation of the disruption of Mcph1 in cells of the indicated genotype. (C) Clonogenic survival analysis of pericentrin- and Mcph1-deficient cells after treatment with the indicated doses of IR. Data points show mean ± s.d. of the surviving fractions in at least three separate experiments. Mean plating efficiencies were: wild-type 115%; PcntΔ/Δ 89%; PcntΔ/ΔMcph1−/− 70%. (D) Analysis of the G2-to-M checkpoint. Cells were captured in mitosis by 0.1 µg/ml colcemid treatment and mitotic indices assessed by flow cytometry for phospho-histone H3 over time. Where indicated, cells were treated with 2 Gy IR. Data points show mean + s.d. from at least three separate experiments in which 10,000 events were analyzed. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy showing centrosome amplification in cells of the indicated genotype stained with antibodies to α-tubulin (green) and γ- tubulin (red), 24h after treatment with 10 Gy IR. DNA was visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. (F) Quantitation of cells of the indicated genotype with aberrant centrosome numbers at the times described after 4mM HU treatment. Histogram shows mean ± s.d. of three separate experiments in which at least 300 cells per experiment were counted. (G and H) Quantitation of cells of the indicated genotype with aberrant centrosome numbers at the times described after 5 Gy IR treatment. Histograms show mean + s.d. of three separate experiments in which at least 300 cells per experiment were counted. NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Centrosome amplification, which can arise from an extended S-phase delay37 or as a Chk1-dependent response to DNA damage,32,38 occurred robustly in pericentrin-deficient cells (Fig. 6E–G). Although we used the PCM component, γ-tubulin, as our centrosome marker in these experiments, we also verified these results with centriolar centrin3 (Fig. S1). Wild-type, PcntΔ/Δ Mcph1−/− and either single mutant showed similar levels of amplification in response to hydroxyurea (HU) treatment, with Mcph1−/− cells showing greatly elevated levels of centrosomes after IR, as previously reported32 (Fig. 6F and G), indicating that DNA damage-induced centrosome amplification and HU-induced centrosome overduplication involve distinct pathways. However, the hyperamplification of centrosomes in response to IR seen in Mcph1−/− cells32 was suppressed by the deletion of Pcnt (Fig. 6G). Notably, this effect was reversed by the re-expression of pericentrin (Fig. 6H), providing clear evidence for the genetic interaction of Pcnt and Mcph1 in determining how the DNA damage response affects centrosomes.

Discussion

We here report the generation and characterization of pericentrin-deficient cells in the DT40 cell line. Although pericentrin deficiency leads to cell cycle arrest in p53-competent cells,15,16 DT40 cells have defective p53 signaling capacity and were expected to proliferate in the absence of pericentrin.39,40 Nevertheless, we aimed to generate a DT40 cell line conditionally null for Pcnt. Given the size of the Pcnt locus and the multiple spliced transcripts it encodes, the promoter-hijack strategy described by Samejima and coworkers seemed ideal for our purpose.35 This approach allowed us to obtain clones with greatly attenuated Pcnt expression and, importantly, by varying tTA levels, we generated rescue clones that showed both wild-type and increased Pcnt expression.

Pericentrin-deficient DT40 cells were viable, although they took longer than controls to complete mitosis, which resulted in slower proliferation than in wild-type cells. Centriolar structure was apparently normal in the absence of pericentrin, with no evidence of multiple or split centrioles, and the majority of the centrosomal markers that we examined were indistinguishable from those in wild-type cells, even though we did not have access to reagents for many PCM components. However, γ-tubulin localization to pericentrin-deficient centrosomes was reduced, as has been seen in other models.4,5,7,18 We also observed a significant increase in the proportion of monopolar spindles, but not to the extent observed in knockdown experiments in HeLa cells.7,18 Knockdown of HeLa PCNT reduced the centrosomal γ-tubulin to approximately 10% of wild-type levels,18 a more dramatic reduction than we observed and one that could impact sufficiently on centrosome maturation to lead to monopolar spindle formation in almost all cells. However, there was no report of monopolar spindles in lymphoblastoid cells from PCNT-SCKL patients, where the centrosomal γ-tubulin levels were reduced only to some 50% of control levels, similar to what we saw in DT40 cells.23 This raises the possibility that cells can adapt to the constitutive deficiency of pericentrin and recruit sufficient factors to mature their centrosomes. Alternatively, there may be some differences in the relative importance of pericentrin for forming a PCM scaffold between lymphoid cells and HeLa cells. Regarding the recently reported requirement for separase cleavage of pericentrin to allow centriole disengagement and licensing for reduplication,19,20 as this process requires the removal of pericentrin, its loss in our knockout model is not likely to prove an impediment to M phase progression.

Despite the reduction in γ-tubulin recruitment to centrosomes, we detected no impact on microtubule nucleation kinetics of the absence of Pcnt, using an assay that measured aster diameter at fixed times after release from a nocodazole-cold block. However, previous work that depleted centrosomal pericentrin using RNAi or chemical inhibition of its assembly found that its loss did reduce centrosomal microtubule nucleation,7,10 although some workers did not see such a reduction.16 We observed longer and more aberrant spindles in pericentrin-deficient cells than in controls, and when pericentrin-deficient cells were challenged with the spindle poisons, nocodazole or taxol, they were slower than wild-type controls in satisfying the spindle checkpoint. We speculate that these observations may reflect a reduction in K-fiber attachment rate, due to the lower γ-tubulin levels in Pcnt-deficient centrosomes. However, we were unable to determine robustly whether this was due to a pericentrin-dependent decline in the number of microtubules emanating from the centrosomes or in the rate of microtubule plus-end extension.

In previous work, we have described centrosome amplification as a Chk1-dependent checkpoint response to DNA damage, with Mcph1 limiting the extent to which this amplification can occur.32,38 Here, we found that pericentrin is not required for robust IR-responsive G2-to-M checkpoint delay or centrosome amplification, and that only a minor increase in radiosensitivity results from Pcnt deficiency. These observations demonstrate that pericentrin is not a direct activator of Chk1 in response to IR. We have not observed the increase in centrosome number in the absence of DNA damage that was described in PCNT mutant human lymphoblastoid cell lines.23 However, this may be a technical issue. As we noted in our description of Mcph1-deficient DT40 cells,32 where we also did not detect centrosome amplification that had been described in MCPH1 mutant patient cells,41 the analysis in human cells was performed after extended nocodazole treatment, which may confound direct comparison of these results.

When we probed the genetic interactions of Pcnt and Mcph1 in the DT40 system, we found no increase of cell cycle delay in response to IR or radiosensitivity in double mutants. We did, however, find a suppression by Pcnt deficiency of the centrosome hyperamplification seen in Mcph1-deficient DT40 cells. As we have previously found that this hyperamplification derives from altered Chk1 activation in Mcph1 mutant cells,32 these data are supportive of a model in which pericentrin acts as a positive regulator of Chk1. However, we do not propose that pericentrin controls Chk1 activation in general. We observed robust spindle checkpoint responses in the absence of Pcnt, contrary to what has been described in Chk1−/− DT40 cells.42 Furthermore, the DNA damage checkpoint that blocks mitotic entry is intact in Pcnt knockouts, unlike in Chk1 nulls.43 Recent mouse work supports an impact of Mcph1 deficiency on centrosomal Chk1, suggesting that pericentrin may affect Chk1 at the centrosome.36 If the key controls on Chk1 depend on its activation through a nuclear-cytosolic/centrosomal feedback loop,44 localization of even a small fraction of Chk1 within the PCM may be a mechanism by which Mcph1 and pericentrin determine its interactions with its regulators.

Materials and Methods

Cloning

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals and oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma, and enzymes used in cloning were obtained from New England BioLabs. A promoter-hijack approach was employed to disrupt the expression of pericentrin as described previously.35 The 5′ homology arm was PCR-amplified from DT40 genomic DNA using KOD polymerase (Novagen/Merck) with the following primers:

5′-agactagtGCTGTGGGAGCTGCTGGATGATAG-3′ and 5′-ctactagtTTGCCTGCCTGCTCTTTCAGAAG-3′. The 3′ homology arm was amplified using: 5′-agacgcgtGACCGAAACTTCTGTGCCTGCC-3′ and 5′-ctacgcgtGCCAGATGCTCTATTGATTTGCCA-3′. The 5′ and 3′ arms were cloned into the SpeI and MluI sites, respectively, of a modified pTRE-tight plasmid that contains a lox P-flanked puro cassette.35

For knocking a FLAG tag into the Pcnt locus, a small fragment containing part of the last intron and the last exon without a stop codon was amplified using 5′-ggatcCTTTATGTGTGAATGTTTGCTTTTG-3′ and 5′-gcggccgcCTTTTTCATGTTTCTTTGGCAAG-3′, then cloned via the BamHI/NotI sites into pC-SF-TAP.45 Next, the 5′ homology arm was amplified using 5′-actagTCAATCGTACTTCAAGTTAGTCCAAG-3′ and 5′-ggatccACCAATGCTCAATCAGAAGAGTACA-3′ and the 3′ homology arm with 5′-ctcgagTCCGAATGCTTCTGAAATCTGT-3′ and 5′-ggtacCAGCACACTCGAAAGAGGACAC-3′. The two homology arms and the tag were cloned into pBluescript using SpeI/BamHI, BamHI/XhoI and XhoI/KpnI digests for assembly. A lox P-flanked blasticidin cassette was inserted into this construct at the BamHI sites.46

The probes for Southern blot were labeled with digoxigenin using the PCR DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche). The Southern probe for the promoter targeting was amplified from genomic DNA using 5′-GCTCTAAGGATATTGAACAGCAGGT-3′ and 5′-GCCCAGCCTTTTGCTCATC-3′ and that for knockin screening, using 5′-TAGACTTTAACCTGCTGTGGACTTG-3′ and 5′-GAAAACCCATGCAAAGAGGATC-3′.

Reverse-transcriptase PCR and quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from DT40 cells using TRI reagent (Ambion/ABI). Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript First-Strand (Invitrogen) and PCR with KOD Hot Start. Primers to amplify Actb and Mcph1 used were described previously.32

Real-time PCR was performed using the ABI7500fast system (ABI). RNA samples extracted with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) were reverse transcribed as above in a total volume of 20 μl. Five µl of a 1:50 dilution was used as a template for each quantitative PCR reaction. Primers for Pcnt were 5′-ACAACTTAGCCAGCATAGGGACT-3′ and 5′-GTTTGTTGAAGGCAGCTTGTTAG-3′. Primers for Actb were 5′-GACACAGATCATGTTTGAGACCTTC-3′ and 5′-ACCAGAGTCCATCACAATACCAGT-3′. Quantitative PCR was performed using PrecisionTM 2 x Quantitative PCR Mastermix (Primer Design). A relative standard curve was made using amplification of serially diluted samples made from asynchronous wild-type cells. The target quantity of each sample is expressed as the fold difference relative to this wild-type calibrator curve. The relative expression levels of Pcnt were obtained by normalizing their expression to a housekeeping gene, β-actin (Actb).

Cell culture, transfection and irradiation

DT40 cells were maintained at 39.5°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 media (Lonza) with the addition of 10% fetal calf serum (Lonza), 1% chicken serum (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma).47 Clonogenic survival assays were performed as described,47 using irradiation with a 137Cs source at 23.5 Gy/min (Mainance Engineering). HU was from Sigma and a 1 M stock solution was made up in DMSO.

Two rounds of targeting were performed to modify the Pcnt locus. Twenty µg of linearized and purified DNA was added to 10 x 106 cells in 0.5 ml PBS. Gene targeting was performed by electroporation using a GenePulser (BioRad) at 300 V/600 µF or 550 V/25 µF, as previously described.47 Twenty-four h after electroporation, cells were placed under selection for 7–10 d with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin or 25 μg/ml blasticidin (Invitrogen). Single clones were then screened by Southern blot. Cre-mediated excision of the drug resistance cassette was performed using nucleofection of 15 µg of endotoxin-free pMer-Cre-Mer46 (solution T, program B-23; Amaxa). Single colonies were obtained by limiting dilution and drug resistance assessed after their expansion. Antibiotic-sensitive clones were further confirmed by Southern blot. To drive expression through the TetO targeted into the promoter region of Pcnt, pKif4A-tTA2 was linearized and stably transfected into Pcnt heterozygotes before the final round of targeting.35 Targeting of Mcph1 in DT40 cells and identification of knockouts were as previously described.32

For microtubule regrowth assays, cells were cultured with 2 μg/ml nocodazole, diluted from a 10 mg/ml stock made up in DMSO (Sigma) for 2 h at 39.5°C, then incubated on ice for additional 2 h to depolymerise microtubules. Cells were subsequently washed three times in ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% DMSO by centrifugation at 250 g for 5 min, then resuspended in this wash solution and deposited on chilled poly L-lysine slides for 30 min at 4°C. To allow microtubule regrowth, slides were submerged in PBS/1% FBS at 40°C for 30 sec or 1 min before methanol fixation. Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to assess microtubule growth. To examine recovery from mitotic arrest, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 12 h for synchronizaton in M phase. Cells were released from the block by washing four times in pre-warmed medium to remove the drug, then cultured in fresh medium for an additional 6 h. Alternatively, cells were cultured in the presence of taxol (Sigma), diluted from a 50 mg/ml stock made up in DMSO. At the indicated time points, cells were collected and examined by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence microscopy and image acquisition

Immunofluorescent cell staining was performed as described previously.48 Cells were spotted onto poly L-lysine-coated slides and fixed for 10 min in pre-chilled 95% methanol/5 mM EGTA at -20°C or 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized in 0.15% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min at room temperature if PFA fixation had been performed. The cells were then blocked in PBS/1% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 45 min at 37°C. Chromosomes and nuclei were counterstained with 1µg/ml DAPI in DABCO [2.5% DABCO (Sigma); 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH8; 90% glycerol].

The primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence analyses were mouse monoclonal anti-Aurora A (35C1; Abcam) at 1:500; monoclonal anti-centrin2 (poly6288; Biolegend) at 1:250; rabbit anti-Cep76 (a gift from Brian Dynlacht49) at 1:200; mouse anti-Cep135 (a gift from Ryoko Kuriyama50) at 1:1000; rabbit polyclonal anti-Ninein (ab4447; Abcam) at 1:100; rabbit polyclonal anti-PCM-1 (817; a gift from Andreas Merdes17) at 1:5000; mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (B512; Sigma) at 1:2000; mouse monoclonal anti-γ-tubulin (GTU88; Sigma) at 1:150; goat polyclonal anti-γ-tubulin (C-20; Santa Cruz) at 1:250; and mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (M2; Sigma) at 1:500. Secondary antibodies were were labeled with FITC and Texas Red and obtained from Jackson Labs.

Cell counting was performed using a BX51 microscope (Olympus), using a 100x oil objective, N.A. 1.35. Images were collected with a DeltaVision integrated microscope system (Applied Precision) mounted on an IX71 microscope (Olympus) with a PlanApo N100x oil objective, N.A. 1.40 and acquired using SoftWorx software (Applied Precision). For the measurement of PCM-1 and γ-tubulin focal intensities, cells were imaged by an Operetta high content imaging system (PerkinElmer) with a 60x air objective. Images were taken and analyzed using Harmony software version 3.0 (PerkinElmer). All images from a single experiment were treated identically.

Live cell imaging

For live cell imaging, cells were stably transfected with a pmRFP-N1-H2B, which encodes red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged histone H2B.51 Before imaging, cells were cultured in media supplemented with 12.5 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) in poly D-lysine-coated dishes (MatTek) for 3 h. Time-lapse images were acquired for 3h at 3 min intervals on a DeltaVision integrated microscope system using a PlanApo N60x oil objective (N.A. 1.42) and a WeatherStation environmental chamber at 39.5°C (Precision Control).

Electron microscopy

DT40 cells were processed for transmission electron microscopy using an established protocol.52 Cell pellets were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Postfixation was performed in a solution of 2% osmium tetroxide/0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Cell pellets were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes (30%; 60%; 90%; 100%) and then infiltrated with propylene oxide. Thereafter, cell pellets were embedded in agar low-viscosity resin with a polymerizaton temperature of 60°C. Serial sections were cut with a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E microtome (Leica), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, then viewed on a H-7000 Electron Microscope (Hitachi). Images were taken with an ORCA-HRL camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) and processed using AMT version 6 (AMT Imaging).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using BD FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences). For one-dimensional cell cycle analyses, cells were collected, fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol and stained with propidium iodide (PI)/RNase A solution. For two-dimensional cell cycle analyses, cells were cultured with 20 µM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for 10 min and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol. After treatment with 2 M HCl/0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 37°C, cells were incubated with 30% anti-BrdU (B44; BD Biosciences) for 1 h and then with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC) anti-mouse (Jackson) for 30 min with shaking at 37°C. To estimate the mitotic index, cells were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol. After treatment with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 min on ice, cells were incubated with anti-phospho-histone H3 Ser10 antibody (#06–570; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, and #9701; Cell Signaling) for 1 h and then secondary antibody and PI/RNase A solution, as above. Apoptotic cells were quantified with annexin V-FITC (a kind gift from Afshin Samali, NUI Galway). Briefly, cells were collected and labeled with annexin V-FITC and PI in calcium buffer (10 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) for 15 min at room temperature.

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA tests were performed with Prism v5.0 (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kumiko Samejima and Bill Earnshaw for plasmids. T.J.D. received a predoctoral fellowship from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal). We are indebted to a PRTLI4 grant to fund the National Biophotonics and Imaging Platform Ireland (www.nbipireland.ie) that supported the TEM. This work was supported by Science Foundation Ireland Principal Investigator awards 08/IN.1/B1029 and 10/IN.1/B2972.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental materials may be found here:

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/23516

References

- 1.Doxsey SJ, Stein P, Evans L, Calarco PD, Kirschner M. Pericentrin, a highly conserved centrosome protein involved in microtubule organization. Cell. 1994;76:639–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flory MR, Moser MJ, Monnat RJ, Jr., Davis TN. Identification of a human centrosomal calmodulin-binding protein that shares homology with pericentrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5919–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Hansen D, Killilea A, Joshi HC, Palazzo RE, Balczon R. Kendrin/pericentrin-B, a centrosome protein with homology to pericentrin that complexes with PCM-1. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:797–809. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Campos M, Basto R, Baker J, Kernan M, Raff JW. The Drosophila pericentrin-like protein is essential for cilia/flagella function, but appears to be dispensable for mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:673–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dictenberg JB, Zimmerman W, Sparks CA, Young A, Vidair C, Zheng Y, et al. Pericentrin and gamma-tubulin form a protein complex and are organized into a novel lattice at the centrosome. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:163–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi M, Yamagiwa A, Nishimura T, Mukai H, Ono Y. Centrosomal proteins CG-NAP and kendrin provide microtubule nucleation sites by anchoring gamma-tubulin ring complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3235–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman WC, Sillibourne J, Rosa J, Doxsey SJ. Mitosis-specific anchoring of gamma tubulin complexes by pericentrin controls spindle organization and mitotic entry. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3642–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaval B, Doxsey SJ. Pericentrin in cellular function and disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:181–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purohit A, Tynan SH, Vallee R, Doxsey SJ. Direct interaction of pericentrin with cytoplasmic dynein light intermediate chain contributes to mitotic spindle organization. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:481–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young A, Dictenberg JB, Purohit A, Tuft R, Doxsey SJ. Cytoplasmic dynein-mediated assembly of pericentrin and gamma tubulin onto centrosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2047–56. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.6.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Malhotra R, Liotta L, Doxsey SJ. Centrosome defects can account for cellular and genetic changes that characterize prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2212–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khodjakov A, Rieder CL, Sluder G, Cassels G, Sibon O, Wang CL. De novo formation of centrosomes in vertebrate cells arrested during S phase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1171–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Terra S, English CN, Hergert P, McEwen BF, Sluder G, Khodjakov A. The de novo centriole assembly pathway in HeLa cells: cell cycle progression and centriole assembly/maturation. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:713–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loncarek J, Hergert P, Magidson V, Khodjakov A. Control of daughter centriole formation by the pericentriolar material. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:322–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikule K, Delaval B, Kaldis P, Jurcyzk A, Hergert P, Doxsey S. Loss of centrosome integrity induces p38-p53-p21-dependent G1-S arrest. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:160–70. doi: 10.1038/ncb1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srsen V, Gnadt N, Dammermann A, Merdes A. Inhibition of centrosome protein assembly leads to p53-dependent exit from the cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:625–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dammermann A, Merdes A. Assembly of centrosomal proteins and microtubule organization depends on PCM-1. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:255–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee K, Rhee K. PLK1 phosphorylation of pericentrin initiates centrosome maturation at the onset of mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:1093–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo K, Ohsumi K, Iwabuchi M, Kawamata T, Ono Y, Takahashi M. Kendrin is a novel substrate for separase involved in the licensing of centriole duplication. Curr Biol. 2012;22:915–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K, Rhee K. Separase-dependent cleavage of pericentrin B is necessary and sufficient for centriole disengagement during mitosis. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2476–85. doi: 10.4161/cc.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyoshi K, Kasahara K, Miyazaki I, Shimizu S, Taniguchi M, Matsuzaki S, et al. Pericentrin, a centrosomal protein related to microcephalic primordial dwarfism, is required for olfactory cilia assembly in mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:3289–97. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-124420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauch A, Thiel CT, Schindler D, Wick U, Crow YJ, Ekici AB, et al. Mutations in the pericentrin (PCNT) gene cause primordial dwarfism. Science. 2008;319:816–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1151174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith E, Walker S, Martin CA, Vagnarelli P, Stiff T, Vernay B, et al. Mutations in pericentrin cause Seckel syndrome with defective ATR-dependent DNA damage signaling. Nat Genet. 2008;40:232–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willems M, Geneviève D, Borck G, Baumann C, Baujat G, Bieth E, et al. Molecular analysis of pericentrin gene (PCNT) in a series of 24 Seckel/microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type II (MOPD II) families. J Med Genet. 2010;47:797–802. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackman M, Lindon C, Nigg EA, Pines J. Active cyclin B1-Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:143–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krämer A, Mailand N, Lukas C, Syljuåsen RG, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA, et al. Centrosome-associated Chk1 prevents premature activation of cyclin-B-Cdk1 kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:884–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löffler H, Bochtler T, Fritz B, Tews B, Ho AD, Lukas J, et al. DNA damage-induced accumulation of centrosomal Chk1 contributes to its checkpoint function. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2541–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt E, Boutros R, Froment C, Monsarrat B, Ducommun B, Dozier C. CHK1 phosphorylates CDC25B during the cell cycle in the absence of DNA damage. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4269–75. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tibelius A, Marhold J, Zentgraf H, Heilig CE, Neitzel H, Ducommun B, et al. Microcephalin and pericentrin regulate mitotic entry via centrosome-associated Chk1. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1149–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enomoto M, Goto H, Tomono Y, Kasahara K, Tsujimura K, Kiyono T, et al. Novel positive feedback loop between Cdk1 and Chk1 in the nucleus during G2/M transition. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34223–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.051540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuyama M, Goto H, Kasahara K, Kawakami Y, Nakanishi M, Kiyono T, et al. Nuclear Chk1 prevents premature mitotic entry. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2113–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown JA, Bourke E, Liptrot C, Dockery P, Morrison CG. MCPH1/BRIT1 limits ionizing radiation-induced centrosome amplification. Oncogene. 2010;29:5537–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flory MR, Davis TN. The centrosomal proteins pericentrin and kendrin are encoded by alternatively spliced products of one gene. Genomics. 2003;82:401–5. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyoshi K, Asanuma M, Miyazaki I, Matsuzaki S, Tohyama M, Ogawa N. Characterization of pericentrin isoforms in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:745–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samejima K, Ogawa H, Cooke CA, Hudson DF, Macisaac F, Ribeiro SA, et al. A promoter-hijack strategy for conditional shutdown of multiply spliced essential cell cycle genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2457–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712083105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruber R, Zhou Z, Sukchev M, Joerss T, Frappart PO, Wang ZQ. MCPH1 regulates the neuroprogenitor division mode by coupling the centrosomal cycle with mitotic entry through the Chk1-Cdc25 pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1325–34. doi: 10.1038/ncb2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prosser SL, Straatman KR, Fry AM. Molecular dissection of the centrosome overduplication pathway in S-phase-arrested cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1760–73. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bourke E, Dodson H, Merdes A, Cuffe L, Zachos G, Walker M, et al. DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent centrosome amplification. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:603–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takao N, Kato H, Mori R, Morrison C, Sonada E, Sun X, et al. Disruption of ATM in p53-null cells causes multiple functional abnormalities in cellular response to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 1999;18:7002–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sui G, Affar B, Shi Y, Brignone C, Wall NR, Yin P, et al. Yin Yang 1 is a negative regulator of p53. Cell. 2004;117:859–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alderton GK, Galbiati L, Griffith E, Surinya KH, Neitzel H, Jackson AP, et al. Regulation of mitotic entry by microcephalin and its overlap with ATR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:725–33. doi: 10.1038/ncb1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zachos G, Black EJ, Walker M, Scott MT, Vagnarelli P, Earnshaw WC, et al. Chk1 is required for spindle checkpoint function. Dev Cell. 2007;12:247–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zachos G, Rainey MD, Gillespie DA. Chk1-deficient tumour cells are viable but exhibit multiple checkpoint and survival defects. EMBO J. 2003;22:713–23. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J, Han X, Feng X, Wang Z, Zhang Y. Coupling cellular localization and function of checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) in checkpoints and cell viability. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25501–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.350397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gloeckner CJ, Boldt K, Schumacher A, Ueffing M. Tandem affinity purification of protein complexes from mammalian cells by the Strep/FLAG (SF)-TAP tag. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;564:359–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-157-8_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arakawa H. Excision of floxed-DNA sequences by transient induction of Mer-Cre-Mer. Subcell Biochem. 2006;40:347–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-4896-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takata M, Sasaki MS, Sonoda E, Morrison C, Hashimoto M, Utsumi H, et al. Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:5497–508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dantas TJ, Wang Y, Lalor P, Dockery P, Morrison CG. Defective nucleotide excision repair with normal centrosome structures and functions in the absence of all vertebrate centrins. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:307–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsang WY, Spektor A, Vijayakumar S, Bista BR, Li J, Sanchez I, et al. Cep76, a centrosomal protein that specifically restrains centriole reduplication. Dev Cell. 2009;16:649–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohta T, Essner R, Ryu JH, Palazzo RE, Uetake Y, Kuriyama R. Characterization of Cep135, a novel coiled-coil centrosomal protein involved in microtubule organization in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:87–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodson H, Wheatley SP, Morrison CG. Involvement of centrosome amplification in radiation-induced mitotic catastrophe. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:364–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.3.3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liptrot C, Gull K. Detection of viruses in recombinant cells by electron microscopy. In: Spiers RE, Griffiths JB, MacDonald C, eds. Animal Cell Technology: Development, Processes and Production. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1992:653–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.