In this document, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) updates its earlier breast-feeding recommendations1 by presenting evidence on interventions that improve the initiation or duration of breast-feeding (or both). Breast-feeding has been shown in both developing and developed countries to improve the health of infants and their mothers, making it the optimal method of infant nutrition.2,3 Although the prevalence of breast-feeding in Canada has risen, with over three-quarters of mothers now initiating breast-feeding, the duration of this practice remains short of the recommended World Health Organization (WHO) targets of exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months and partial breast-feeding for up to 2 years.4,5 Recent Canadian data indicate that 22% of recent mothers aged 15–49 years breast-feed for less than 3 months, and 35% do so for at least 3 months.6 This premature discontinuation is more a result of difficulty with breast-feeding, including lack of information and support, than of women's choice.7 In fact, the number of Canadian hospitals that would qualify as “baby-friendly” according to WHO–UNICEF criteria8 was 5 of 523 hospitals responding to a 1993 survey,9 and according to UNICEF only a single hospital had that designation in 2002.10

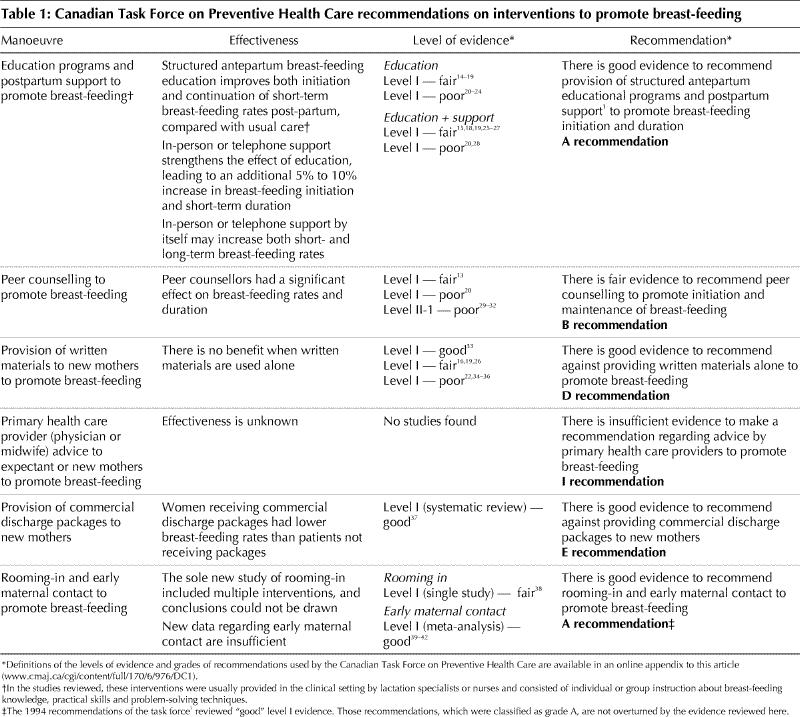

In a joint endeavour, the CTFPHC and the US Preventive Services Task Force systematically reviewed the randomized trial evidence for the effectiveness of all counselling interventions originating in a clinician's practice (such as antepartum and postpartum support groups, education, telephone support or peer counsellors) to increase the rate of initiation or the duration of breast-feeding.11,12 We present here the new CTFPHC recommendations, based on the joint systematic review as well as a key Canadian trial13 published after that review and tailored to the Canadian health care setting (Table 1). Definitions of the levels of evidence and grades of recommendations used in Table 1 are available in an online appendix to this article (www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/170/6/976/DC1).

Table 1

Interventions consisting of antepartum structured breast-feeding education are effective at improving both initiation and continuation of breast-feeding during the first 2 months postpartum, compared with usual care.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28These interventions, consisting of individual or group instruction about breast-feeding knowledge, practical skills and problem-solving techniques, were effective when provided by lactation specialists or nurses, and both single sessions and multiple sessions were effective. Postpartum telephone or in-person support by lactation specialists, nurses or peer counsellors enhanced the effectiveness of these interventions. In addition, the use of peer counsellors improved breast-feeding rates and duration, and these types of programs may represent a cost-effective alternative to professionally delivered services, especially in locations or settings where professional services are scarce or not available.13,20,29,30,31,32 The CTFPHC recommends against the use of written materials (which have not been shown to be effective when used alone,16,19,22,26,33,34,35,36 although no harm was demonstrated) and commercial discharge packages (which have been shown to decrease breast-feeding rates).37 Unfortunately, advice from a woman's primary clinician (such as family physician, obstetrician or midwife) has not been sufficiently evaluated, and a research gap remains in this area.

The recommendations presented here (Table 1) do not address the clinical benefits of breast-feeding, which the CTFPHC felt had been established by its earlier breast-feeding recommendations;1 instead, we have concentrated on recommendations about interventions that change the initiation and duration of breast-feeding.

The Canadian Paediatric Society, Dieticians of Canada and Health Canada have recommended exclusive breast-feeding for at least the first 4 months of life, then continuation of breast-feeding along with complementary foods for up to 2 years and beyond.43 The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended exclusive breast-feeding for approximately the first 6 months after birth and continued breast-feeding for at least 12 months and thereafter for as long as mutually desired.44 Provision of adequate individual and systems-based supports, such as recommended in the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative,8 are also recommended by most groups.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Valerie Palda reviewed the evidence and drafted the recommendations and this commentary. Jeanne-Marie Guise and Nadine Wathen reviewed the evidence and draft recommendations, critically revised the current article and reviewed subsequent revisions. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care critically reviewed the evidence and developed the recommendations according to its methodology and consensus development process. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care is an independent panel funded by Health Canada.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, 117–700 Collip Circle, London ON N6G 4X8; fax 519 858–5112; ctf@ctfphc.org

References

- 1.Wang EEL. Breastfeeding. In: Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Canadian guide to clinical preventive health care. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1994. p. 232-42.

- 2.Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Shapiro S, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA 2001;285(4):413-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet 2002;360(9328):187-95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: report of an expert consultation. Geneva: The Organization; 2002. Available: www.who.int/nut/documents/optimal_duration_of_exc_bfeeding_report_eng.pdf (accessed 2004 Feb 16).

- 5.World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: The Organization; 2003. Available: www.who.int/nut/documents/gs_infant_feeding_text_eng.pdf (accessed 2004 Feb 16).

- 6.Breastfeeding practices. Health Indic [serial online] 2002;2002(1). Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002 May. Cat no 82-221-XIE. Available: www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82-221-XIE/00502/high/canada/cbreast.htm (accessed 2004 Feb 19).

- 7.Barber CM, Abernathy T, Steinmetz B, Charlebois J. Using a breastfeeding prevalence survey to identify a population for targeted programs. Can J Public Health 1997;88(4):242-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.World Health Organization. Evidence for the ten steps to successful breastfeeding. Geneva: The Organization; 1998. Available: www.who.int/child-adolescent-health/New_Publications/NUTRITION/WHO_CHD_98.9.pdf (accessed 2004 Feb 16).

- 9.Dunlop M. Few Canadian hospitals qualify for “Baby Friendly” designation by promoting breast-feeding: survey. CMAJ 1995;152(1):87-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Current status of baby-friendly hospital initiative: March 2002 [table online]. New York: UNICEF; 2002. Available: www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/assets/statusbfhi.pdf (accessed 2004 Feb 16).

- 11.Guise JM, Palda V, Westhoff C, Chan BKS, Helfand M, Lieu TA. The effectiveness of primary care-based interventions to promote breastfeeding: systematic evidence review and meta-analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Fam Med 2003;1:70-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Palda VA, Guise JM, Wathen CN, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Interventions to promote breastfeeding: updated recommendations from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CTFPHC Tech Rep 03-6. London (ON): Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2003 Oct.

- 13.Dennis CL, Hodnett E, Gallop R, Chalmers B. The effect of peer support on breast-feeding duration among primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2002;166(1):21-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Duffy EP, Percival P, Kershaw E. Positive effects of an antenatal group teaching session on postnatal nipple pain, nipple trauma and breastfeeding rates. Midwifery 1997;13(4):189-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Pugh LC, Milligan RA. Nursing intervention to increase the duration of breastfeeding. Appl Nurs Res 1998;11(4):190-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hill PD. Effects of education on breastfeeding success. Matern Child Nurs J 1987;16(2):145-56. [PubMed]

- 17.Kistin N, Benton D, Rao S. Breastfeeding rates among black urban low income women: effect of prenatal education. Pediatrics 1990;86:741-6. [PubMed]

- 18.Brent NB, Redd B, Dworetz A, D'Amico F, Greenberg JJ. Breast-feeding in a low-income population. Program to increase incidence and duration. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995;149(7):798-803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Redman S, Watkins J, Evans L, Lloyd D. Evaluation of an Australian intervention to encourage breastfeeding in primiparous women. Health Promot Int 1995;10(2):101-13.

- 20.Sciacca JP, Dube DA, Phipps BL, Ratliff MI. A breastfeeding education and promotion program: effects on knowledge, attitudes, and support for breastfeeding. J Community Health 1995;20(6):473-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.McEnery G, Rao KP. The effectiveness of antenatal education of Pakistani and Indian women living in this country. Child Care Health Dev 1986;12(6):385-99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rossiter JC. The effect of a culture-specific education program to promote breastfeeding among Vietnamese women in Sydney. Int J Nurs Stud 1994;31(4):369-79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Wiles LS. The effect of prenatal breastfeeding education on breastfeeding success and maternal perception of the infant. JOGN Nurs 1984;13(4):253-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Reifsnider E, Eckhart D. Prenatal breastfeeding education: its effect on breastfeeding among WIC participants. J Hum Lact 1997;13(2):121-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Oakley A, Rajan L. Social support and pregnancy outcome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:155-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Frank DA, Wirtz SJ, Sorenson JR, Heeren T. Commercial discharge packs and breastfeeding counseling: effects on infant-feeding practices in a randomized trial. Pediatrics 1987;80(6):845-54. [PubMed]

- 27.Serafino-Cross P, Donovan P. Effectiveness of professional breastfeeding home support. J Nutr Educ 1992;24(3):117-22.

- 28.Jones D, West R. Lactation nurse increases duration of breastfeeding. Arch Dis Child 1985;60:772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Caulfield LE, Gross SM, Bentley ME, Bronner Y, Kessler L, Jensen J, et al. WIC-based interventions to promote breastfeeding among African-American Women in Baltimore: effects on breastfeeding initiation and continuation. J Hum Lact 1998;14(1):15-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Schafer E, Vogel MK, Viegas S, Hausafus C. Volunteer peer counselors increase breastfeeding duration among rural low-income women. Birth 1998;25:101-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kistin N, Abramson R, Dublin P. Effect of peer counselors on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration among low-income urban women. J Hum Lact 1994;10(1):11-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.McInnes R, Love J, Stone D. Evaluation of a community-based intervention to increase breastfeeding prevalence. J Hum Lact 2000;22:138-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Curro V, Lanni R, Scipione F, Grimaldi V, Mastroiacovo P. Randomised controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of a booklet on the duration of breastfeeding. Arch Dis Child 1997;76(6):500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Kaplowitz DD, Olson CM. The effect of an educational program on the decision to breastfeed. J Nutr Educ 1983;15:61-5.

- 35.Loh NR, Kelleher CC, Long S, Loftus BG. Can we increase breast feeding rates? Ir Med J 1997;90(3):100-1. [PubMed]

- 36.Grossman LK, Harter C, Sachs L, Kay A. The effect of postpartum lactation counseling on the duration of breastfeeding in low-income women. Am J Dis Child 1990;144(4):471-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Donnelly A, Snowden H, Renfrew M, Woolridge M. Commercial hospital discharge packs for breastfeeding women [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 3, 2001. Oxford: Update Software.

- 38.Winikoff B, Myers D, Laukaran VH, Stone R. Overcoming obstacles to breastfeeding in a large municipal hospital: applications of lessons learned. Pediatrics 1987;80(3):423-3. [PubMed]

- 39.De Chateau P, Wiberg B. Long-term effect on mother—infant behaviour of extra contact during the first hour post partum. II. A follow-up at three months. Acta Paediatr Scand 1977;66:145-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Salariya E, Easton P, Cater J. Duration of breastfeeding after early initiation and frequent feeding. Lancet 1978;2:1141-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Thomson M, Hartsock T, Larson C. The importance of immediate postnatal contact: its effect on breastfeeding. Can Fam Physician 1979;25:1374-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Taylor PM, Maloni JA, Taylor FH, Campbell SB. Extra early mother–infant contact and duration of breast-feeding. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 1985;316:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Nutrition for healthy term infants. Statement of the Joint Working Group: Canadian Paediatric Society, Dieticians of Canada, Health Canada. Ottawa: Minister of Health; 1998. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dca-dea/publications/pdf/infant_e.pdf (accessed 2004 Feb 16).

- 44.American Academy of Pediatrics, Work Group on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 1997;100(6):1035-9. Available: aappolicy .aappubli cations .org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics%3b100/6/1035 (accessed 2004 Feb 16).9411381

- 45.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(3 Suppl):21-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.