Abstract

Infection of macrophages by the human intestinal commensal Enterococcus faecalis generates DNA damage and chromosomal instability in mammalian cells through bystander effects. These effects are characterized by clastogenesis and damage to mitotic spindles in target cells and are mediated, in part, by trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE). In this study we investigated the role of cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) in producing this reactive aldehyde using E. faecalis-infected macrophages and interleukin-10 knockout mice colonized with this commensal. 4-HNE production by E. faecalis-infected macrophages was significantly reduced by COX and LOX inhibitors. The infection of macrophages led to decreased Cox1 and Alox5 expression while COX-2 and 4-HNE increased. Silencing Alox5 and Cox1 with gene-specific siRNAs had no effect on 4-HNE production. In contrast, silencing Cox2 significantly decreased 4-HNE production by E. faecalis-infected macrophages. Depleting intracellular glutathione increased 4-HNE production by these cells. Next, to confirm COX-2 as a source for 4-HNE, we assayed the products generated by recombinant human COX-2 and found 4-HNE in a concentration-dependent manner using arachidonic acid as a substrate. Finally, tissue macrophages in colon biopsies from interleukin-10 knockout mice colonized with E. faecalis were positive for COX-2 by immunohistochemical staining. This was associated with increased staining for 4-HNE-protein adducts in surrounding stroma. These data show that E. faecalis, a human intestinal commensal, can trigger macrophages to produce 4-HNE through COX-2. Importantly, it reinforces the concept of COX-2 as a procarcinogenic enzyme capable of damaging DNA in target cells through bystander effects that contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Cyclooxygenase-2, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, carcinogenesis, colorectal cancer, macrophage, commensal

Introduction

Cyclooxygenases (COX) and lipoxygenases (LOX) produce a variety of biologically important prostanoids, leukotrienes, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, and lipoxins through the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (1). These important signaling molecules help regulate numerous physiological responses including inflammation, cellular proliferation, vascular and bronchial airway tone, and tissue hemostasis. COX occurs as a constitutive form (COX-1) in most tissues and an inducible form (COX-2) that is typically expressed in response to environmental triggers such as infection, physical irritants, growth factors, and cytokines. There are several LOX isoforms with arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX5 or 5-lipoxygenase) expressed primarily in inflammatory cells and dependent upon the arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein. COX and LOX pathways have been implicated in carcinogenesis. For example, prolonged exposure to aspirin, an irreversible COX inhibitor, significantly reduces the overall risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) and mortality from CRC in human trials (2). Observational and randomized clinical trials of NSAIDs and COX-2-specific inhibitors demonstrate reductions in colorectal adenomas (3). Similar decreases in adenoma formation are noted in ApcMin/+ and ApcΔ716 mice when Cox is inactivated (4,5). Finally, ALOX5 is overexpressed in colon polyps and CRC (6), much like COX-2 (7), with inhibition impairing tumor growth and attenuating polyps in ApcMin/+ mice (8). The mechanisms by which COX-2 or ALOX5 initiate mutations to drive the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence, however, remain unclear.

PGE2 and PGD2 are major COX-2-derived products that promote cancer cell growth by modulating signaling cascades for cellular proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and immune surveillance (9). ALOX5 produces 5(S)-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid, a precursor for leukotrienes that are signaling molecules in asthmatic, allergic, and inflammatory reactions (1). Although these lipid mediators promote diverse biological functions, they are not mutagens and seem unlikely to initiate tumors. Each enzyme, however, produces products that can be reduced to hydroxyeicosatetraenoic or hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (1). Arachidonic acid, the primary ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid substrate for COX-2, can also be oxidized by this enzyme to reactive carbonyl compounds such as 4-oxo-2-nonenal, 4-hydroperoxy-2-nonenal, 4-hydroxy-2E,6Z-dodecadienal, and trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) (10). These bifunctional electrophiles can diffuse across cellular membranes to form adducts with proteins, phospholipids, and DNA. Among these, 4-HNE has been most intensively studied. This α,β-unsaturated aldehyde is a signaling molecule for cellular stress (11), induces COX-2 (12), inhibits DNA repair (13), reacts with DNA (1), damages microtubules and mitotic spindles (14,15), and potentially contributes to chromosomal instability (CIN) (15,16).

The carcinogenic effects of non-prostanoid byproducts derived from COX-2 were investigated using rat intestinal epithelial cells overexpressing this enzyme (17). A 3-fold increase in heptanone-etheno-DNA adducts was observed in the presence of ascorbate that served to promote the decompostion of bifunctional electrophiles that were generated (17). Stereoisomeric analysis identified these adducts as lipid peroxidation byproducts of arachidonic acid that were generated by COX-2. Others investigators, however, using colon cancer cell lines failed to correlate DNA adduct levels with COX-2 activity (18). Finally, as mentioned above, ALOX5 also generates products that can be converted to lipid hydroperoxides and potentially decompose into DNA-damaging electrophiles (1).

COX-2 and ALOX5 are not ordinarily expressed in healthy colons. In colonic adenomas, however, COX-2 expression is found in mucosal macrophages, but not epithelial celss where cellular transformation leads to cancer (7). In contrast, ALOX5 is abundantly expressed in epithelial cells in adenomas (6). These temporospatial relationships, when considered in the context of clinical and animal data (2–6,8), implicate these enzymes in colorectal carcinogenesis.

Using interleukin (IL)-10 knockout mice, we have recently linked the common intestinal commensal Enterococcus faecalis to COX-2 induction in macrophages and to transforming events in epithelial cells (19,20). E. faecalis is a minority constituent of the mammalian intestinal microbiota that generates extracellular superoxide and oxidative stress under conditions of heme deprivation (21). The unusual redox physiology activates bystander effects (BSE) in macrophages and causes CRC in IL-10 knockout mice (15,19). BSE is recognized by genomic damage in target cells that are exposed to diffusible clastogens (or chromosome-breaking factors) from activated myeloid and/or fibroblast cells (22,23). Historically, these effects occur following irradiation. However, we discovered that macrophages infected by E. faecalis can also produce BSE that include double-strand DNA breaks, aneuploidy, tetraploidy, and CIN (15,19,20). This genomic damage, whether due to BSE from irradiated or infected cells, depends in part on COX-2 (19,24), although the diffusible mediators remain ill-defined. We and others have suggested 4-HNE as one such mediator because it can cause DNA damage and act as a spindle poison to produce tetraploidy in target cells (15,16). As such, this reactive aldehyde represents a potential link between COX-2 catalysis and CIN.

In this study we show that E. faecalis-infected macrophages produce increased amounts of 4-HNE in a COX-2, but not ALOX5, dependent fashion. In addition, using IL-10 knockout mice colonized by E. faecalis, we demonstrate increased COX-2 expression in colonic macrophages in association with 4-HNE-protein adducts. These data suggest that colonic macrophages, when triggered by an intestinal commensal such as E. faecalis, can induce COX-2 and thereby increase the production of 4-HNE, a diffusible mutagen. These findings reinforce the role of COX-2 as a pro-carcinogenic enzyme that is able to endogenously initiate transforming events leading to CRC.

Materials and Methods

Cells, bacteria, and chemicals

Murine macrophages (RAW264.7 cells; American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin G, and streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. E. faecalis strain OG1RF, a human oral isolate, and the spectinomycin- and streptomycin-derivative strain OG1RFSS were grown in brain heart infusion (BD Diagnostics) and used for macrophage infection and to colonize mice, respectively, as previously described (15). In brief, RAW264.7 cells were treated with OG1RF at a multiplicity of infection of 1000 in antibiotic- and serum-free Dulbecco’s for 2 hrs at 37°C. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated in complete medium supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 gentamicin for 24 hrs at 37°C. Supernatants were collected for 4-HNE analysis and cell pellets lysed for protein and RNA analyses. The COX-2-specific inhibitor celecoxib was kindly provided by C.V. Rao. The ALOX5 specific inhibitor AA861 (2-(12-hydroxydodecane-5,10-diynyl)-3,5,6-trimethyl-p-benzo-quinone), and COX and LOX inhibitor ETYA (eicosatetraynoic acid) were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (25). Buthionine sulphoximine (BSO) was obtained from Sigma.

4-HNE and PGD2 analysis

Lipids were extracted from supernatants by the Folch procedure and reconstituted in 100% ethanol as previously described (15). Extracts were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography using reversed-phase chromatography coupled to a 4-cell electrochemical detector as previously described (15).

COX-2 catalysis of arachidonic acid

Reactions were performed in a thermostatic cuvette (Gilson Medical Electronics) with 1 ml of 100 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4) containing 100 μM arachidonic acid (Cayman), 1 μM hematin (Sigma), and 2 units of human recombinant COX-2 (Cayman) at 37°C. Reactions were terminated at 5 min by adding butylated hydroxytoluene and depletion of oxygen. Mixtures were extracted and separated by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography with 4-HNE and arachidonate metabolites determined by electrochemical detection as previously described (15). Enzyme activity was measured by O2 uptake using an Oxygen Probe Amplifier equipped with a Clarke-type electrode (Harvard Apparatus).

siRNA and RT-PCR

Cox1, Cox2, and Alox5 were silenced by RNA interference using siGENOME SMARTpool siRNAs or with siCONTROL Non-Targeting siRNA Pool (Dharmacon). Transient transfections were performed using DharmaFECT 4 Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol and gene silencing confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blot.

Total RNA was isolated from RAW264.7 cells using the NucleoSpin RNA II Kit (BD Biosciences). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized at 37°C using TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Primers and cycling parameters are shown in the Supplementary Table.

Western blots

Protein extraction, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting were performed as previously described (20). Goat polyclonal antibody for COX-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-ALOX5 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Thermo Scientific) were used as primary antibodies. Rabbit anti-goat IgG HRP conjugate (Millipore) and goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP conjugate (Cell Signaling Technology) were used for secondary antibodies. Signals were generated by Amersham™ ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) and images captured using the ChemiDoc™ XRS+ System (Bio-Rad).

Colonization of Il10−/− mice

Conventionally housed Il10−/− knockout mice (C57Bl/6J, Jackson Laboratory) were orogastrically inoculated with 1 × 109 colony forming units of E. faecalis OG1RFSS, or PBS as sham, as previously described (26). Colonization was confirmed by plating stools on enterococcal agar (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with streptomycin and spectinomycin. After 9 months, mice were sacrificed and colons fixed for immunostaining. Animal protocols were approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center IACUC and Oklahoma City Department of Veterans Affairs Animal Studies Committee.

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously described. For COX-2 staining, slides were blocked with 5% normal rabbit serum, incubated with goat anti-COX-2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz), and stained with rabbit anti-goat IgG HRP conjugate (Millipore). Slides were developed with DAB Enhanced liquid substrate and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin solution (Sigma).

Immunofluorescent staining for macrophages (F4/80) and COX-2 or 4-HNE was performed as previously described (27). Goat anti-COX-2 antibody (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-4-HNE antibody (Alpha Diagnostic International), and rat anti-F4/80 antibody (eBioscience) were used as primary antibodies. Anti-goat IgG FITC, anti-rabbit IgG FITC, and anti-rat IgG Texas Red (Santa Cruz) were used as secondary antibodies. Cells were counterstained with 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and images collected using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as means with SDs. Groups were compared using Student’s t test with P values < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

LOX and COX inhibitors decrease 4-HNE production by macrophages

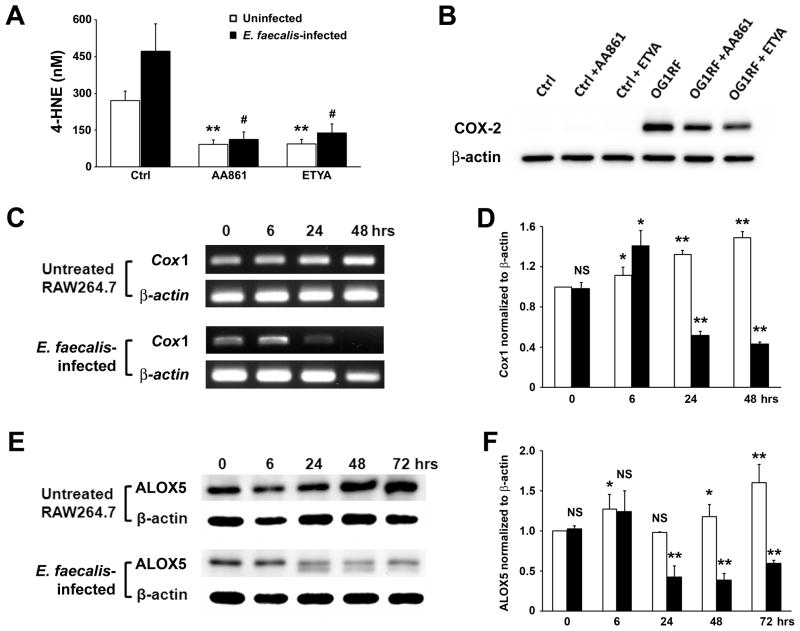

E. faecalis-infected macrophages produce increased 4-HNE, a lipid peroxidation byproduct of arachidonic acid (15). Since cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases catalyze reactions using this ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and 4-HNE is a known breakdown product, we explored the role of these enzymes in increased 4-HNE production from infected murine macrophages. Initially, we treated uninfected macrophages with an ALOX5-specific inhibitor and a dual COX/LOX inhibitor. Both inhibitors decreased background levels of 4-HNE in supernatants from 252 ± 35 to 85 ± 18 and 87 ± 16 nM for AA861 and ETYA, respectively (Fig. 1A, P < 0.01). These inhibitors also decreased 4-HNE production when macrophages were infected with E. faecalis (439 ± 104 to 105 ± 28 and 128 ± 34 nM for AA861 and ETYA, respectively, P = 0.01). Of note, COX-2, which is not measurably expressed by these macrophages under ordinary culture conditions, is strongly induced by E. faecalis (19), and was less strongly induced in the presence of these inhibitors following infection (Fig. 1B). In contrast, COX-1 and ALOX5 were constitutively expressed by uninfected RAW264.7 cells and each decreased following E. faecalis infection (Fig. 1C–F). These changes made it difficult to determine whether the reduction in 4-HNE production caused by these inhibitors was due to enzyme inhibition vs. changes in enzyme expression in infected macrophages.

Figure 1. Inhibitors for ALOX5 and COX decrease 4-HNE production from macrophages.

A, AA861 (ALOX5 inhibitor) and ETYA (inhibitor for ALOX5 and COX) significantly decrease 4-HNE production in supernatants from uninfected (open bar) and E. faecalis-infected macrophages (solid bar, **P < 0.01; #P = 0.01 compared to control). B, Western blots show decreased COX-2 in macrophages by AA861 and ETYA following treatment with E. faecalis. C, RT-PCR shows decreased Cox1 expression in E. faecalis-infected macrophages (lower panel) compared to uninfected macrophages (upper panel). D, Normalized Cox1 expression increases in untreated macrophages (open bar) while decreases following E. faecalis-infection (solid bar). E, Western blots for ALOX5 in uninfected macrophages (upper panel) and E. faecalis-infected macrophages (lower panel). F, Normalized ALOX5 production decreases at 24–72 hrs following E. faecalis-infection (solid bar) compared to uninfected macrophages (open bar; NS, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared to untreated control at zero time point for D and F). Data represent mean ± SD for 3 independent experiments.

COX-1 and ALOX5 are not sources of 4-HNE for infected macrophages

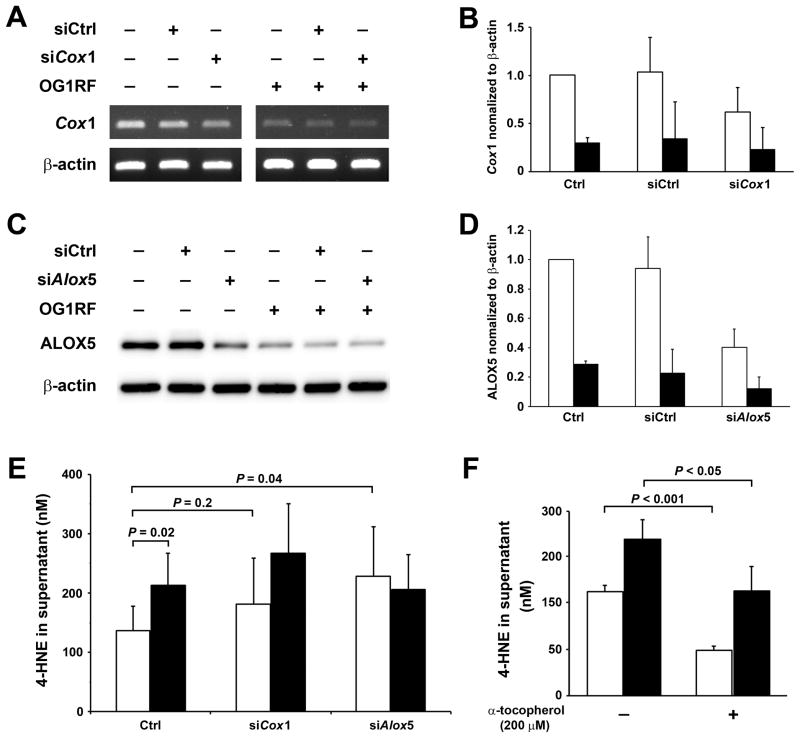

To assess potential contributions of COX-1 or ALOX5 to 4-HNE production in E. faecalis-infected macrophages, Cox1 and Alox5 were silenced using siRNA and 4-HNE production measured. RT-PCR showed a 38% decrease in Cox1 expression for cells transfected with Cox1-specific siRNA compared to cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA (Fig. 2A and 2B). Similarly, a 60% reduction was noted in Alox5 expression using Alox5-specific siRNA compared to control (Fig. 2C and 2D). Although the expression of Cox1 and Alox5 decreased slightly in E. faecalis-infected macrophages transfected with gene-specific siRNAs compared to non-targeting siRNA, these effects were largely overwhelmed by the strong inhibition of gene expression for these enzymes in infected macrophages (Fig. 2A–2D). No decrease was observed in 4-HNE production for Cox1-silenced macrophages compared to controls (P = 0.24 and 0.22, for either uninfected or E. faecalis-infected macrophages, respectively). Similarly, no change was noted in 4-HNE production for Alox5-silenced macrophages following E. faecalis infection compared to control. Of note, 4-HNE production modestly increased in Alox5-silenced uninfected macrophages compared to non-transfected controls (P = 0.04, Fig. 2E). Although ALOX5 expression is typically associated with increased lipid peroxidation (28), this observation may represent a perturbation and increase in non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation from the loss of ALOX5 endproducts.

Figure 2. Silencing Cox1 and Alox5 fail to reduce 4-HNE production.

A and B, RT-PCR shows that Cox1-specific siRNA (siCox1) significantly decreases Cox1 expression in uninfected (open bar) and E. faecalis-infected macrophages (solid bar) compared to non-targeting siRNA (siCtrl). C and D, Western blots show Alox5-specific siRNA (siAlox5) decreases ALOX5 in both uninfected (open bar) and E. faecalis-infected macrophages (solid bar) compared to siCtrl. E, Significantly increased 4-HNE production is seen in E. faecalis-infected macrophages (solid bar) compared with uninfected macrophages (open bar). Of note, silencing Cox1 and Alox5 does not decrease 4-HNE production by E. faecalis-infected macrophages (P = 0.2 and P = 0.8, respectively). F, α-tocopherol significantly decreases 4-HNE production in uninfected (open bar) and E. faecalis-infected macrophages (solid bar). Data represent mean ± SD for 6 independent experiments for 4-HNE assays and 3 independent experiments for other measures.

We tested the hypothesis that 4-HNE produced by macrophages derives in part from non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation using α-tocopherol, a potent terminator of lipid peroxidation chain reactions with no effect on COX-2 expression (19). We found that α-tocopherol significantly decreased 4-HNE production from both uninfected and E. faecalis-infected macrophages, suggesting non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation was in part a source for the basal production of 4-HNE by these cells (Fig. 2F). In summary, the expression of Cox1 and Alox5 decreased in E. faecalis-infected macrophages as these cells otherwise were producing increased amounts of 4-HNE. Partial silencing of these genes resulted in either no change, or a trend toward increased 4-HNE production. These observations indicate that Cox1 and Alox5 were not significant sources for 4-HNE in E. faecalis-infected macrophages.

COX-2 produces 4-HNE

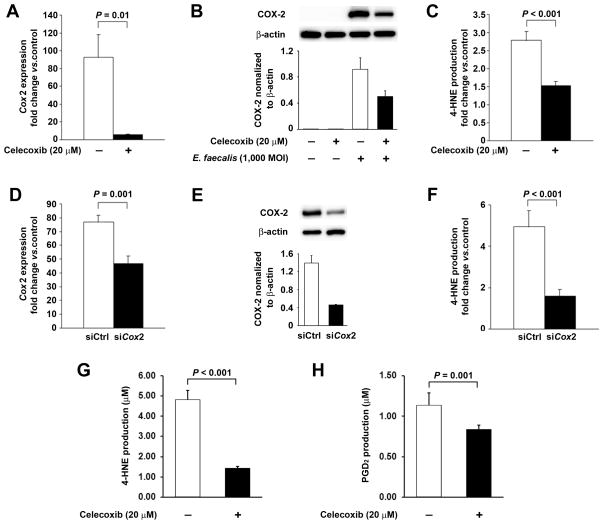

The lack of association of Cox1 or Alox5 with 4-HNE production led us to more closely investigate the role of Cox2. Initially, we pretreated macrophages with celecoxib—COX-2-specific inhibitor—prior to infection with E. faecalis. RT-PCR showed a 94% decrease in Cox2 expression compared to untreated E. faecalis-infected controls (P = 0.01, Fig. 3A). These findings suggest that celecoxib not only blocks the active site of COX-2 but also suppresses Cox2 transcription. Western blotting showed a 46% decrease in COX-2 expression in E. faecalis-infected macrophages that were treated with celecoxib (Fig. 3B). This observation is consistent with previous reports (29). Of note, the inhibition of COX-2 by celecoxib was associated with a 45% decrease in 4-HNE production following E. faecalis infection (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C). Since celecoxib may have off-target effects, we transfected macrophages with Cox2-specific siRNA and observed a 35% decrease in Cox2 expression and 67% decrease in COX-2 protein after E. faecalis infection (P = 0.001, Fig. 3D and 3E). This was associated with a 68% decrease in 4-HNE production compared to infected macrophages that were transfected with non-targeting siRNA (P < 0.001, Fig. 3F). These findings confirm COX-2 as the predominant source for increased 4-HNE in E. faecalis-infected macrophages.

Figure 3. COX-2 is the predominant source for 4-HNE.

A, Celecoxib significantly decreases E. faecalis-induced Cox2 expression in macrophages. B. Western blots confirm significantly decreased COX-2 in E. faecalis-infected macrophages treated with celecoxib. C, Celecoxib significantly decreases 4-HNE production in E. faecalis-infected macrophages. D, Cox2-specific siRNA (siCox2) decreases Cox2 expression in E. faecalis-infected macrophages compared to non-targeting siRNA (siCtrl). E, Western blots shows remarkably decreased COX-2 production in E. faecalis-infected macrophages transfected with Cox2 siRNA (siCox2) compared to non-targeting siRNA (siCtrl). F, siCox2 decreases 4-HNE production in E. faecalis-infected macrophages compared to siCtrl. G, Celecoxib significantly inhibits 4-HNE production by recombinant human COX-2 with 50 μM arachidonic acid as the substrate. H, Similarly, celecoxib significantly decreases PGD2 production by recombinant human COX-2.

To directly assess the ability of COX-2 to generate 4-HNE, we tested recombinant human COX-2 in vitro using arachidonic acid as substrate. We discovered that 4-HNE was produced in a concentration-dependent manner as a significant byproduct of catalysis. When the reaction was allowed to go to completion using 50, 100, or 2000 μmol arachidonate as substrate, 18, 36, and 1,560 μmols 4-HNE were detected, respectively, in final reaction mixtures. Controls using buffer and substrate, but no enzyme, did not produce detectable 4-HNE. Celecoxib decreased 4-HNE production by 71% when 50 μmol arachidonic acid was used as the substrate (Fig. 3G). This was associated with 27% decrease in PGD2 production—a decomposition product of PGH2 (Fig. 3H). These observations offer additional support for COX-2 as the primary source of 4-HNE from infected macrophages.

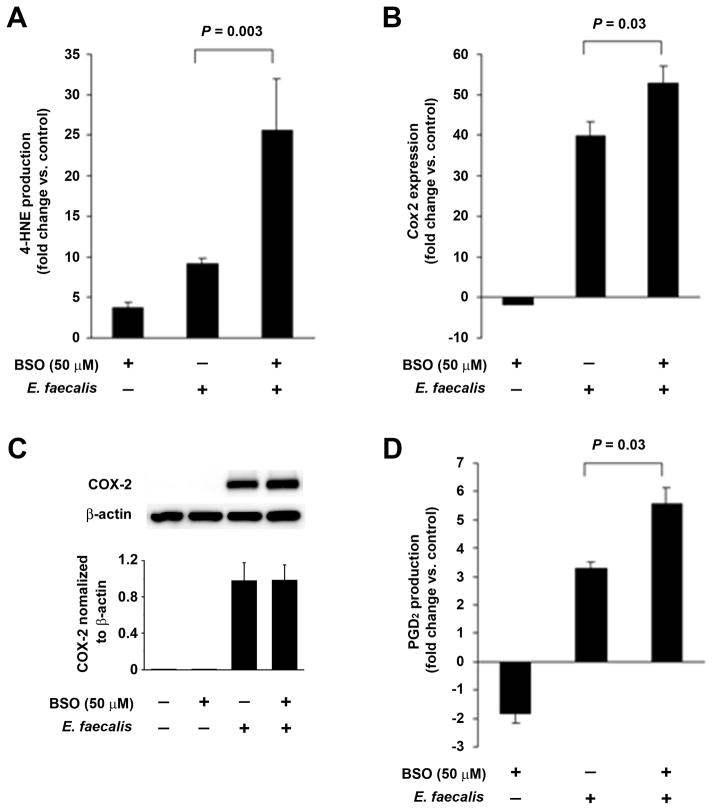

Glutathione depletion increases 4-HNE production by E. faecalis-infected macrophages

We previously showed that 4-HNE mediates genotoxicity through macrophage-induced BSE (15). Since glutathione is required for enzymatic scavenging of 4-HNE by glutathione S-transferase, we investigated the effect of BSO, a γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase inhibitor that depletes intracellular glutathione and enhances genotoxicity (20,30), on 4-HNE production. In comparison to E. faecalis-infected controls, a 2.5-fold increase in 4-HNE production was seen for BSO-treated macrophages that were infected with E. faecalis (P = 0.003, Fig. 4A). A 1.3-fold increase in Cox2 expression was evident in these same macrophages (P = 0.03, Fig 4B). Since 4-HNE can specifically induce COX-2, this response might represent positive feedback by this electrophile (12). Although Cox2 expression appeared slightly suppressed by BSO in uninfected macrophages (Fig. 4B), this was not confirmed at the protein level (Fig. 4C). Finally, COX-2 activity, as measured by production of PGD2, increased 5.7-fold following BSO treatment of E. faecalis-infected macrophages compared to 3.3-fold for untreated macrophages infected with E. faecalis (P = 0.03, Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. 4-HNE increases COX-2 via positive feedback.

A, Normalized to uninfected macrophages, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) increases 4-HNE production in E. faecalis-infected and uninfected macrophages. B, Normalized to uninfected macrophages, Cox2 expression decreases 2-fold following BSO treatment. Normalized to control, BSO treatment of E. faecalis-infected macrophages increases Cox2 expression by 50-fold. Cox2 expression is further increased when BSO is added to E. faecalis-infected macrophages compared to control. C, Western blots show no effect on COX-2 production when BSO is added. D, BSO significantly increases PGD2 in E. faecalis-infected macrophages when normalized to control, suggesting that 4-HNE increases COX-2 activity. Fold changes represent values normalized to untreated macrophages. Data are means ± SD for experiments performed in triplicate.

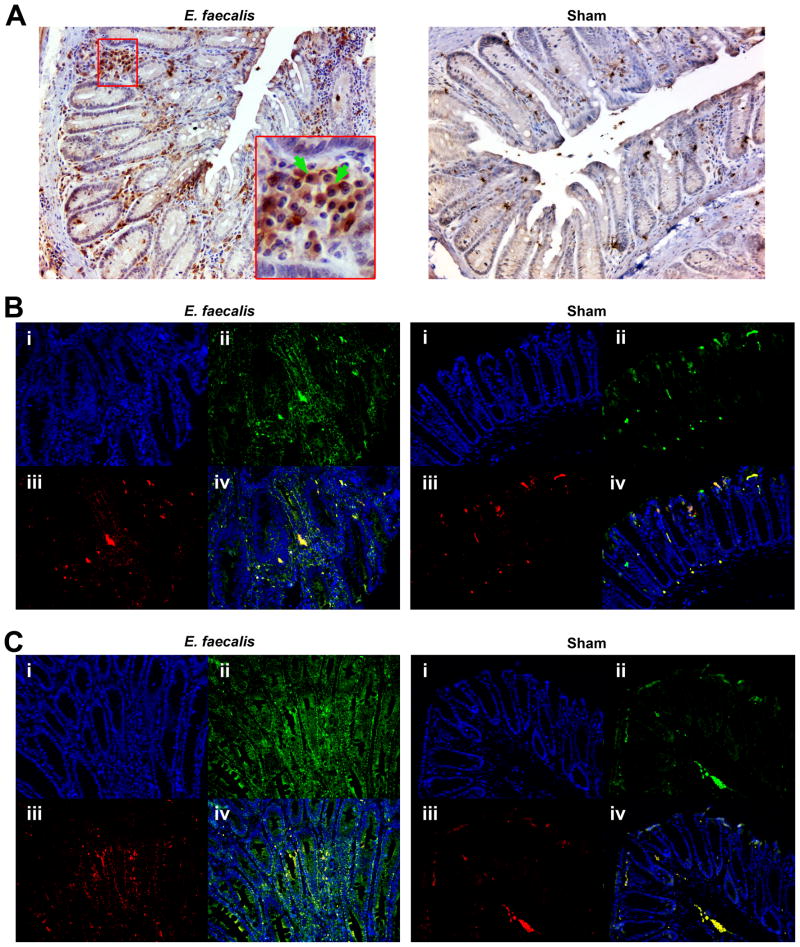

Co-localization of COX-2 and 4-HNE in colonized Il10−/− mice

Il10−/− mice colonized with E. faecalis develop colon inflammation and CRC (31). These pathological changes are associated with increased 4-HNE-protein adducts in colonic mucosal cells and stroma (15). To further examine the mechanism for these events, we stained colon biopsies from E. faecalis-colonized Il10−/− mice for COX-2 and 4-HNE-protein adducts. Immunohistochemistry showed intense staining for COX-2 in macrophages in areas of inflammation (Fig. 5A). In comparison, we saw little to no staining for sham-colonized mice. Immunofluorescence showed similarly increased COX-2 expression in colonic macrophages (Fig. 5B) with markedly increased 4-HNE-protein adduct staining in macrophages and, compared to shams, associated intercellular spaces (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. 4-HNE co-localizes to macrophages expressing COX-2.

A, Immunohistochemical staining for COX-2 (brown) in colon sections from Il10−/− mice colonized with E. faecalis (left) or sham (right) for 9 months. COX-2 is seen in macrophages (green arrows) in areas of inflammation. No COX-2 is noted in colon sections from sham-colonized Il10−/− mice. B, Immunofluorescence staining for COX-2 (ii, green) and F4/80 (iii, red) confirm co-localization of COX-2 to macrophages (iv, yellow). DNA is counter-stained using DAPI (i, blue). Significantly increased COX-2-positive cells are seen in sections from E. faecalis-colonized Il10−/− mice (left) compared to sham (right). C, Immunofluorescence staining for 4-HNE-protein adducts (ii, green) and F4/80 (iii, red) shows focal staining of 4-HNE in macrophages (iv, yellow) and diffuse staining on crypts (green) for E. faecalis-colonized mice (left) compared to minimal staining for sham-colonized mice (right).

Discussion

These data demonstrate COX-2 as a predominant source for 4-HNE following macrophage infection by E. faecalis. In addition, staining for 4-HNE-protein adducts was noted in the colonic stroma and tissue macrophages of Il10−/− mice colonized by E. faecalis. This intestinal commensal is a trigger for colitis and CRC in this model (15,31). By comparison, COX-1 and ALOX5 did not contribute to 4-HNE production. These findings help link COX-2 to clastogenesis caused by BSE (19,24). In the context of associations between this enzyme and carcinogenesis (1,3–5,32), COX-2 should be considered an autochthonous source for mutagenesis leading to cellular transformation.

The role of COX-2 in CRC has been recognized for many years (2,9,33). Several lines of evidence derive from animal models where tumorigenesis is curtailed after Cox is deleted or inhibited (4,5). Although major products downstream from COX-2—PGE2 and PGD2—are diffusible and promote cellular growth (9), these lipid mediators are not mutagenic and seem unlikely to initiate cellular transformation. COX-2, however, can produce less well recognized byproducts that include 4-oxo-2-nonenal, 4-hydroperoxy-2-nonenal, 4-hydroxy-2E,6Z-dodecadienal, and 4-HNE (1). As amphiphilic aldehydes, these compounds can readily form adducts with proteins, phospholipids, and DNA (1,10,11,14).

4-HNE and related carbonyl compounds are most often thought of as being derived from ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids due to oxidative stress (10,11). These reactive aldehydes can form in cellular membranes from fatty acids via non-enzymatic pathways and potentially represent a major source of 4-HNE in tissue culture for cells not expressing COX-2 (28). Our findings, however, describe COX-2 as another important source for 4-HNE. We propose that the induction of this enzyme in macrophages, and subsequent increase in 4-HNE production, overwhelms scavenging mechanisms for this aldehyde in epithelial cells, viz., glutathione S-transferases (15,34), and results in ongoing genomic damage that leads to cellular transformation.

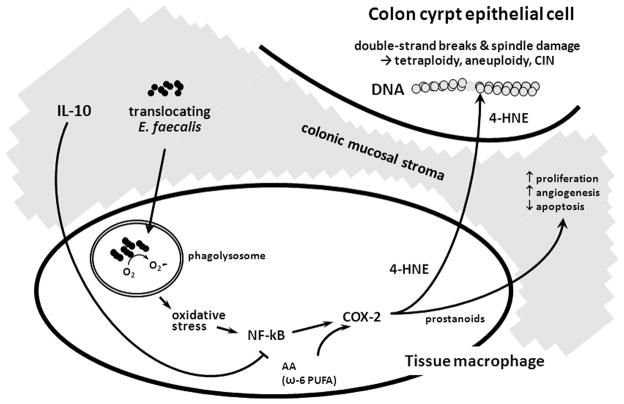

Any plausible theory for sporadic CRC should address the role of COX-2 in carcinogenesis, describe the origin of CIN, and elucidate the relationship between reactive stromal cells and colonic epithelial cells. Our proposed model for autochthonous mutagenesis mechanistically links these characteristics for inflammation-associated and sporadic CRC (Fig. 6). The lack of COX-2 expression in normal colonic mucosa, with strong expression in tissue macrophages in human adenomas, is consistent with a theory for human CRC that is caused by commensal-triggered and macrophage-induced BSE (7). We propose that specific commensals such as E. faecalis serve as triggers for innate immune responses that drive mutagenesis through BSE.

Figure 6. Il10−/− model for bystander effects due to E. faecalis-infected macrophages.

Translocating E. faecalis are phagocytosed by tissue macrophages with superoxide contributing to peroxidation oxidative stress, NF-κB signaling, and COX-2 expression that generates clastogenic lipid peroxidation byproducts (e.g., trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal [4-HNE]). 4-HNE diffuses to nearby colonic epithelial cells to cause bystander effects (BSE). 4-HNE reacts with DNA to form mutagenic adducts and to cause CIN (1,11,15); prostanoids are derived from COX-2 and limit apoptosis, enhance angiogenesis, and promote proliferation in epithelial cells but are not mediators of BSE.

This hypothesis joins the oxidative physiology of E. faecalis to the expression of COX-2 in colonic macrophages. We postulate that extracellular superoxide from E. faecalis generates clastogens by chronically activating macrophages through ongoing infection. E. faecalis must translocate the intact intestinal epithelium for this to occur. This is a trait that has been previously described for this genus (35). In addition, enterococci must persist in macrophages despite the otherwise lethal effects of phagocytosis—again, this is a recognized phenotype for E. faecalis (36). Macrophages respond to E. faecalis infection by activating nuclear factor-κB and inducing COX-2 (37). Following this sequence of signaling events, as shown here, COX-2 is induced and generates mutagenic 4-HNE (and possibly related congeners although they were not specifically investigated in this study). As an amphiphilic aldehyde, 4-HNE can readily diffuse into nearby epithelial cells to stochastically damage DNA that, over long periods, leads to CIN.

The phenomenon of BSE is readily demonstrated using supernatants from irradiated cells to induce CIN in non-irradiated cells (22). Congenic sex-mismatch bone marrow transplant studies kin mice have confirmed that BSE occurs in vivo (38). BSE is not exclusively induced by irradiation. Superoxide also triggers this phenomenon with DNA damage prevented by superoxide dismutase (19,23). Mediators for radiation- or superoxide-induced clastogenesis, however, have remained elusive. Potential candidates include long-lived lipid radicals, byproducts of lipid peroxidation, inositol, and TNF-α (16,23,39). A clue into these mediators was reported by Zhou et al. who described their dependence on COX-2 (24). Our laboratory similarly implicated this enzyme using infected macrophages (19,20). In this paper, we expand on these earlier observations by showing COX-2 is a source for 4-HNE. Further evaluation of this using COX-2 inhibitors in IL-10 knockout mice would be difficult since these drugs paradoxically cause severe colitis (40). Genetically inactivating COX-2 in tissue macrophages using Cre mice is a potential alternative approach. In sum, these results link an intestinal commensal to BSE and provide additional evidence for 4-HNE as a bona fide mediator of clastogenesis (15,16).

A focus on E. faecalis in the Il10−/− model should not be construed to mean that other intestinal commensals do not have the potential to serve as triggers for BSE and clastogenesis. Conversely, it is unlikely that any member of the colonic microbiota can cause CRC. Indeed, the vast majority of commensals co-exist as symbiotes and promote health while excluding potentially pathogenic exogenous bacteria (41). Commensals may even lower the risk for CRC. Strains of Escherichia coli express enterotoxins with anti-proliferative properties (42). Despite these caveats, accumulating evidence provides a strong rationale for considering colonic commensals as sources for endogenous DNA damage in colorectal carcinogenesis. Similar to E. faecalis, E. coli can generate double-strand DNA breaks in mammalian cells and CRC in monoassociated Il10−/− mice when expressing an unusual hybrid peptide-polyketide toxin (43). Strains of Bacteroides fragilis can produce an enterotoxin that induces colonic tumors in ApcMin/+ mice (44). Finally, a role of commensals in colorectal carcinogenesis is found in diverse murine models for CRC where, in nearly every instance, including the IL-10 knockout model, germ-free or pathogen-free derivatives have a reduced tumor burden or fail to develop CRC (31,45–49).

Collectively, these studies suggest that certain commensals or, more accurately, pathobioants can damage epithelial cell DNA and help drive colorectal carcinogenesis. Notwithstanding, these models have weaknesses. Commensals do not cause inflammation or CRC in healthy wildtype mice. Deficiencies in host immunity (e.g., Il10−/−) are typically necessary for cellular transformation by E. faecalis. Despite this caveat, the Il10−/− model, is useful for studying mechanisms that may contribute to human carcinogenesis.

In sum, our findings support a novel mechanism of inflammation-associated and sporadic CRC. This theory involves specific pathobioants (e.g., E. faecalis) that trigger abnormal innate immune responses that induce BSE, cause DNA damage in epithelial cells, and initiate CIN. The key effector in this scheme is COX-2 with its ability to generate 4-HNE. This theory, if confirmed in human tissue, will open new avenues for preventing these cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NIH CA127893 (to M.M.H.), the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology HR10-032 (to X.W.), and the Frances Duffy Endowment.

Abbreviations

- CIN

chromosomal instability

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- 4-HNE

trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- BSO

buthionine sulfoximine

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- LOX

lipoxygenases

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Speed N, Blair IA. Cyclooxygenase- and lipoxygenase-mediated DNA damage. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:437–47. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, Patrono C. The role of aspirin in cancer prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:259–67. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chulada PC, Thompson MB, Mahler JF, Doyle CM, Gaul BW, Lee C, et al. Genetic disruption of Ptgs-1, as well as Ptgs-2, reduces intestinal tumorigenesis in Min mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oshima M, Dinchuk JE, Kargman SL, Oshima H, Hancock B, Kwong E, et al. Suppression of intestinal polyposis in Apc delta716 knockout mice by inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) Cell. 1996;87:803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81988-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melstrom LG, Bentrem DJ, Salabat MR, Kennedy TJ, Ding XZ, Strouch M, et al. Overexpression of 5-lipoxygenase in colon polyps and cancer and the effect of 5-LOX inhibitors in vitro and in a murine model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6525–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapple KS, Cartwright EJ, Hawcroft G, Tisbury A, Bonifer C, Scott N, et al. Localization of cyclooxygenase-2 in human sporadic colorectal adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:545–53. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheon EC, Khazaie K, Khan MW, Strouch MJ, Krantz SB, Phillips J, et al. Mast cell 5-lipoxygenase activity promotes intestinal polyposis in APCΔ468 mice. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1627–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Dubois RN. Prostaglandins and cancer. Gut. 2006;55:115–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negre-Salvayre A, Coatrieux C, Ingueneau C, Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poli G, Schaur RJ, Siems WG, Leonarduzzi G. 4-hydroxynonenal: a membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Med Res Rev. 2008;28:569–631. doi: 10.1002/med.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumagai T, Matsukawa N, Kaneko Y, Kusumi Y, Mitsumata M, Uchida K. A lipid peroxidation-derived inflammatory mediator: identification of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal as a potential inducer of cyclooxygenase-2 in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48389–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng Z, Hu W, Tang MS. Trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal inhibits nucleotide excision repair in human cells: a possible mechanism for lipid peroxidation-induced carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8598–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402794101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neely MD, Boutte A, Milatovic D, Montine TJ. Mechanisms of 4-hydroxynonenal-induced neuronal microtubule dysfunction. Brain Res. 2005;1037:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Yang Y, Moore DR, Nimmo SL, Lightfoot SA, Huycke MM. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal mediates genotoxicity and bystander effects caused by Enterococcus faecalis-infected macrophages. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:543–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emerit I, Khan SH, Esterbauer H. Hydroxynonenal, a component of clastogenic factors? Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;10:371–7. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Williams MV, Dubois RN, Blair IA. Cyclooxygenase-2-mediated DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28337–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma RA, Gescher A, Plastaras JP, Leuratti C, Singh R, Gallacher-Horley B, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2, malondialdehyde and pyrimidopurinone adducts of deoxyguanosine in human colon cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1557–60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Huycke MM. Extracellular superoxide production by Enterococcus faecalis promotes chromosomal instability in mammalian cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:551–61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Allen TD, May RJ, Lightfoot S, Houchen CW, Huycke MM. Enterococcus faecalis induces aneuploidy and tetraploidy in colonic epithelial cells through a bystander effect. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9909–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huycke MM, Moore D, Joyce W, Wise P, Shepard L, Kotake Y, et al. Extracellular superoxide production by Enterococcus faecalis requires demethylmenaquinone and is attenuated by functional terminal quinol oxidases. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:729–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorimore SA, Wright EG. Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects: related inflammatory-type responses to radiation-induced stress and injury? A review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emerit I. Reactive oxygen species, chromosome mutation, and cancer: possible role of clastogenic factors in carcinogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;16:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Gillespie J, Geard CR, Amundson SA, Brenner DJ, et al. Mechanism of radiation-induced bystander effect: role of the cyclooxygenase-2 signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14641–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505473102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong SH, Avis I, Vos MD, Martinez A, Treston AM, Mulshine JL. Relationship of arachidonic acid metabolizing enzyme expression in epithelial cancer cell lines to the growth effect of selective biochemical inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2223–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huycke MM, Abrams V, Moore DR. Enterococcus faecalis produces extracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide that damages colonic epithelial cell DNA. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:529–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Wang X, Moore DR, Lightfoot SA, Huycke MM. TNF-alpha mediates macrophage-induced bystander effects through netrin-1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5219–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider C, Tallman KA, Porter NA, Brash AR. Two distinct pathways of formation of 4-hydroxynonenal. Mechanisms of nonenzymatic transformation of the 9- and 13-hydroperoxides of linoleic acid to 4-hydroxyalkenals. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20831–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak YE, Jeon NK, Kim J, Lee EJ. The cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor celecoxib suppresses proliferation and invasiveness in the human oral squamous carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1095:99–112. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drew R, Miners JO. The effects of buthionine sulphoximine (BSO) on glutathione depletion and xenobiotic biotransformation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:2989–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SC, Tonkonogy SL, Albright CA, Tsang J, Balish EJ, Braun J, et al. Variable phenotypes of enterocolitis in IL-10 deficient mice monoassociated with two different commensal bacteria. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:891–906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer SM, Hawk ET, Lubet RA. Coxibs and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in animal models of cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1728–35. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marnett LJ, DuBois RN. COX-2: a target for colon cancer prevention. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:55–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082301.164620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engle MR, Singh SP, Czernik PJ, Gaddy D, Montague DC, Ceci JD, et al. Physiological role of mGSTA4-4, a glutathione S-transferase metabolizing 4-hydroxynonenal: generation and analysis of mGsta4 null mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells CL, Barton RG, Wavatne CS, Dunn DL, Cerra FB. Intestinal bacterial flora, intestinal pathology, and lipopolysaccharide-induced translocation of intestinal bacteria. Circulatory Shock. 1992;37:117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baldassarri L, Cecchini R, Bertuccini L, Ammendolia MG, Iosi F, Arciola CR, et al. Enterococcus spp. produces slime and survives in rat peritoneal macrophages. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2001;190:113–20. doi: 10.1007/s00430-001-0096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen TD, Moore DR, Wang X, Casu V, May R, Lerner MR, et al. Dichotomous metabolism of Enterococcus faecalis induced by haematin starvation modulates colonic gene expression. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1193–204. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47798-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson GE, Lorimore SA, Macdonald DA, Wright EG. Chromosomal instability in unirradiated cells induced in vivo by a bystander effect of ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5608–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waldren CA, Vannais DB, Ueno AM. A role for long-lived radicals (LLR) in radiation-induced mutation and persistent chromosomal instability: counteraction by ascorbate and RibCys but not DMSO. Mutat Res. 2004;551:255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hegazi RA, Mady HH, Melhem MF, Sepulveda AR, Mohi M, Kandil HM. Celecoxib and rofecoxib potentiate chronic colitis and premalignant changes in interleukin 10 knockout mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:230–6. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitari GM, Zingman LV, Hodgson DM, Alekseev AE, Kazerounian S, Bienengraeber M, et al. Bacterial enterotoxins are associated with resistance to colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2695–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434905100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S, Rhee KJ, Albesiano E, Rabizadeh S, Wu X, Yen HR, et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat Med. 2009;15:1016–22. doi: 10.1038/nm.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maggio-Price L, Treuting P, Zeng W, Tsang M, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Iritani BM. Helicobacter infection is required for inflammation and colon cancer in SMAD3-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:828–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engle SJ, Ormsby I, Pawlowski S, Boivin GP, Croft J, Balish E, et al. Elimination of colon cancer in germ-free transforming growth factor beta 1-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kado S, Uchida K, Funabashi H, Iwata S, Nagata Y, Ando M, et al. Intestinal microflora are necessary for development of spontaneous adenocarcinoma of the large intestine in T-cell receptor beta chain and p53 double-knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2395–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dove WF, Clipson L, Gould KA, Luongo C, Marshall DJ, Moser AR, et al. Intestinal neoplasia in the ApcMin mouse: independence from the microbial and natural killer (beige locus) status. Cancer Res. 1997;57:812–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu FF, Esworthy RS, Doroshow JH. Role of Se-dependent glutathione peroxidases in gastrointestinal inflammation and cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1481–95. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.