Abstract

Purpose

Myocardial perfusion studies using dynamic contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) could provide valuable, quantitative information regarding heart physiology in diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), that lead to diffuse myocardial damage. The goal of this effort was to develop an intuitive but physiologically meaningful method for quantifying myocardial perfusion by CMRI and to test its ability to detect global myocardial differences in a dog model of DMD.

Methods

A discrete-time model was developed that parameterizes contrast agent kinetics in terms of an uptake coefficient that describes the forward flux of contrast agent into the tissue, and a retention coefficient that describes the rate of decay in tissue concentration due to contrast agent efflux. This model was tested in 5 dogs with DMD and 6 healthy controls which were imaged using a perfusion sequence on a 3T clinical scanner. CINE and delayed-enhancement CMRI acquisitions were also used to assess cardiac function and the presence of myocardial scar.

Results

Among functional parameters measured by CMRI, no significant differences were observed. No myocardial scar was observed. Increased perfusion in DMD was observed with an uptake coefficient of 6.76% ± 2.41% compared to 2.98% ± 1.46% in controls (p=0.03). Additionally, the retention coefficient appeared lower at 82.2% ± 5.8% in dogs with DMD compared to 90.5% ± 6.6% in controls (p=0.12).

Conclusions

A discrete-time kinetic model of uptake and retention of contrast agent in perfusion CMRI shows potential for the study of DMD.

Keywords: Myocardial perfusion, MRI, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, contrast agents, kinetic models

INTRODUCTION

The use of first-pass contrast-enhanced CMRI to identify myocardial perfusion deficits at rest or under stress has shown prognostic value in detecting significant coronary occlusive disease, assessing the risk of cardiovascular events, and identifying the presence of hibernating myocardium post infarct [1–7]. Perfusion CMRI studies may also provide quantitative information regarding myocardial physiology through approaches based on contrast agent kinetic modeling [8] Such quantitative information can be especially valuable in cardiac pathologies leading to diffuse changes in myocardial properties that are too subtle to recognize based on direct inspection of the images themselves.

One potential application of quantitative perfusion CMRI is assessing the degree of cardiac involvement in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). DMD is a fatal, X-linked, recessive muscle disease caused by lack of dystrophin due to mutations in the dystrophin gene. DMD affects both skeletal and cardiac muscles [9, 10]. Due to the increasingly common use of ventilatory support, cardiomyopathy has become the leading cause of morbidity (seen in nearly all patients) and mortality (~40%) in DMD patients [11, 12]. In addition, more than 50% of DMD carriers also present with cardiac symptoms [11–13]. CMRI may be helpful in staging and detecting early impacts of DMD in the myocardium. In particular, perfusion CMRI may reveal vascular changes or the existence of diffuse fibrosis in the myocardium. Previous reports have shown that DMD patients exhibit a high prevalence of scar by delayed enhancement CMRI [14–16]. Perfusion studies involving PET and SPECT imaging have reported deficits in patients with DMD [17, 18]. Studies involving perfusion CMRI, however, have not been reported.

Among the challenges in applying quantitative perfusion CMRI to diseases such as DMD is the potential for global changes in perfusion that cannot be recognized as regional differences. This challenge is compounded by the lack of a concise display and simple interpretation of the quantitative results. Previous methods for quantifying perfusion CMRI results have focused either on semi-quantitative measurements, such as the upslope of the myocardial uptake curve, or kinetic models with specific physiological measurements, such as the mean transit time [8, 19–24]. These measurements often lack a clear physiological context or else portray information that is difficult to understand by those who are not well-versed in the underlying model.

Thus, the purpose of this study was two-fold. First, we sought to develop an analysis approach that automatically extracts a map of perfusion characteristics and communicates the characteristics in terms of intuitive but physiologically meaningful parameters. Second, we sought to test this approach in a canine model of DMD. DMD-affected dogs represent the only animal model that faithfully mimics human DMD, reproducing many of its elements including cardiomyopathy. The affected dogs typically die from cardiac or respiratory malfunctions within 2 to 4 years of birth [25], making this a meaningful preclinical model for testing out the approach.

METHODS

Canine model

Research was performed according to the principles outlined in the Guide for Laboratory Animal Facilities and Care prepared by the National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council. Dogs were housed in kennels certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. All dogs were immunized for leptospirosis, distemper, hepatitis, papillomavirus and parvovirus, dewormed, and observed for disease for at least 2 months before study.

MRI protocol

All dogs were imaged with a CMRI protocol that included CINE imaging, dynamic contrast enhanced CMRI and delayed enhancement imaging. For scanning, the animals were sedated with acepromazine 0.025 mg/kg; 0.04 mg/kg/atropine; and butorphanol 0.1–0.2 mg/kg, iv. All studies were conducted on a 3T MRI system (Philips Achieva, Best, Netherlands). CINE images were acquired with a turbo field echo (TFE) sequence that generated 30 cardiac phases for 8 to 10 short axis slices spanning the left ventricle. Acquisition parameters included a repetition time (TR) / echo time (TE) of 4.7/2.3 msec, a 15 degree flip angle, 4 mm slice thickness with 2 mm gaps, and an in-plane resolution of 2 mm × 1.67 mm. The dynamic perfusion sequence was a mid-ventricle, single-slice, single-shot saturation recovery TFE acquisition with TR/TE of 3.0/1.4 msec, 20 degree flip angle, 5 mm slice thickness and in-plane resolution of 1.99 mm × 1.96 mm. During the acquisition, 0.1 mmol/kg Gd-DTPA (Magnevist, Bayer Schering Health Care Limited, UK) was manually injected, followed by a saline flush. At 10 minutes after injection, three-dimensional delayed-enhancement images were acquired with an inversion-recovery TFE sequence. Acquisition parameters were TR/TE of 4/1.27 msec, 15 degree flip angle, resolution of 1.48 mm × 1.76 mm × 10 mm, TFE factor 24 and SENSE factor 1.5.

Kinetic model

To model the contrast agent dynamics, we used a discrete time approximation of the Kety model as previously used in perfusion CMRI [21] and given by

| (Equation 1) |

where Ktrans is the transfer constant and kep is the transfer rate constant, Cp(t) is the plasma concentration, and Ct(t) is the tissue concentration. Equation 1 has also been formulated in terms of the myocardial blood flow (MBF), extraction efficiency (EE), and partition coefficient (λ) [24]. The resulting equation is obtained by making the following replacements in Equation 1:

Numerical integration of Equation 1 under an assumption of piece-wise constant plasma concentration yields

| (Equation 2) |

where Cp[n] and Ct[n] are, respectively, the plasma and tissue concentrations in frame n of the image series,

and ΔT is the time step between image frames. Alternatively, this model can be written

| (Equation 3) |

which invites a simple interpretation of the model components. First, UCp[n] is the total forward flux of contrast agent into the tissue over one time frame. The term RCt[n − 1] is the amount of contrast agent still remaining in the tissue from the previous time frame (i.e. the amount not lost to efflux). We refer to the parameters U and R as the uptake and retention, respectively.

To solve for U and Rwe set up the linear equation

| (Equation 4) |

which has a closed-form solution. Finally, to eliminate the dependence of the model parameters on ΔT, we normalize the results to 1-second intervals and define the uptake and retention coefficients as

Quantitative perfusion analysis

Quantitative perfusion analysis was performed by an expert in kinetic modeling (WK) with 10 years experience. The discrete kinetic model was implemented into a custom quantitative perfusion analysis package programmed in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) and based on similar analysis tools for perfusion analysis of artery wall images [26, 27]. In this program, a time series of frames was extracted from the dynamic sequence starting at the frame immediately before bolus arrival in the right ventricle and ending 30 seconds later. The frame with approximately maximal enhancement of the left ventricle chamber was also identified. Then, an automatic registration algorithm [26] was run in both directions from the frame of maximal enhancement within an 8.75 cm × 8.75 cm region of interest centered on the left ventricle. Each frame was matched to the previous one by identifying the in-plane shift that minimized the sum of the square roots of the absolute differences between pixel values.

Next, an automatic arterial input function (AIF) extraction algorithm [27] was used to identify an enhancement-versus-time curve representing the blood within the left ventricle chamber. Enhancement-versus-time curves were extracted from all pixels within a 7-pixel × 7-pixel region at the center of the chamber. For each pixel, all pixels with similar curves were identified via a mean shift algorithm, and the mean curve for those pixels was found. The AIF was identified as the mean curve based on at least 5 pixels, with maximal enhancement.

Finally, maps of the uptake and retention coefficients were computed for every pixel within the region of interest using Equation 4. Concentration was assumed to be proportional to the change in signal intensity. In addition, an average tissue curve for the entire myocardium was extracted by averaging all pixels within manually drawn epicardial and endocardial boundaries. The model parameters were then extracted from this average curve to obtain a single overall value for the myocardium. For the overall value, model parameters were obtained from the non-linear Equation 2 using a gradient descent algorithm with R constrained to be less than or equal to 100%. The non-linear formulation was found to yield less fitting error than Equation 4 for quantitative analyses.

Cardiac functional analysis

In addition to the perfusion analysis, functional parameters were computed from the CINE images using a ViewForum Workstation (Philips, Best, Netherlands). Epicardial and endocardial boundaries of the left ventricle were interactively traced at end-diastole and end-systole by an expert (AN) with 9 years experience in cardiac analysis. Based on the boundaries, the following measurements were obtained: end-systolic volume (ESV), end-diastolic volume (EDV), stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), cardiac output (CO), and left ventricular mass (LVM). Finally, delayed enhancement CMRI results were qualitatively assessed for the presence of focal areas of enhancement.

Data analysis

Comparisons between measurements from DMD dogs and normal controls were assessed by two-sided Student’s t-tests. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study involved 5 dogs with DMD and 6 normal controls. Ages for dogs with DMD averaged 41 ± 38 months (range: 12 to 98) and weight averaged 14.33±1.8 kg (range 11.7 to 16.5kg). Healthy controls had mean age 20 ± 4 months (range: 15 to 25) and weight averaged 12.2±3.26 kg (range 9.3 to 16.3 kg). All DMD dogs were confirmed by genotyping and increased serum creatine kinase level. Clinical signs of the disease varied among the 5 dogs. While the 3 younger DMD-affected dogs (aged 12, 13 and 17 months) showed obvious clinical symptoms, including difficulties in eating, walking and breathing, the two older affected dogs (aged 5 years 2 months, and 8 years 2 months) were in generally good health.

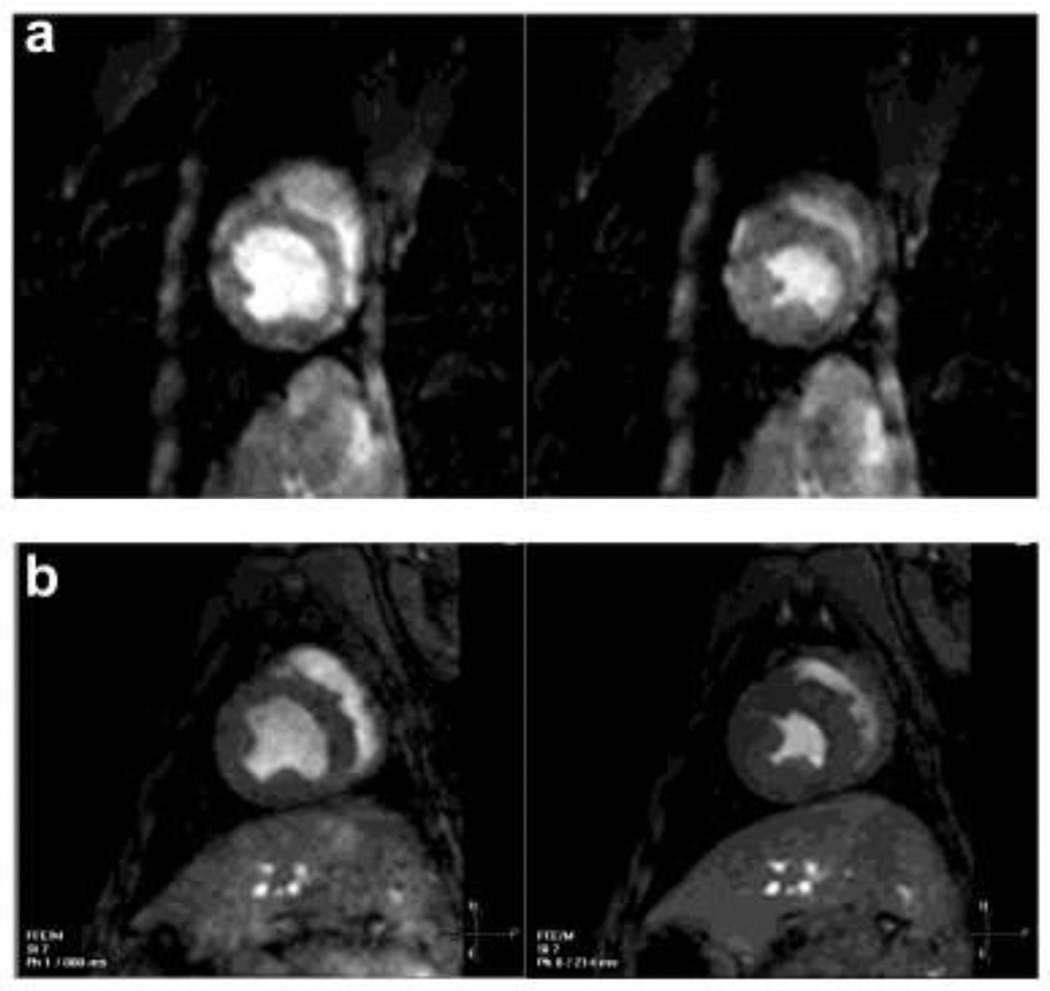

Cardiac functional parameters for dogs with DMD and healthy controls are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in functional parameters were observed other than dogs with DMD having higher heart rates compared to normal controls (170 versus 111 bpm, p=0.01). Although not significantly different, EF tended to be lower in dogs with DMD. Of the 5 dogs exhibiting EF<55%, 4 (80%) were from the DMD group. Comparisons of end-diastolic and end-systolic images from dogs with DMD and normal controls are shown in Figure 1. The statistical comparison of EF was impacted by an outlying value from a dog with DMD that exhibited the highest EF (71.4%) and was by far the oldest in the study at more than 8 years. Without this dog, the difference in EF approached statistical significance (p=0.06). Finally, no evidence of focal delayed enhancement was observed in any dogs, indicating a lack of identifiable infarcted tissue.

Table 1.

Cardiac functional parameters (mean ± standard deviation) comparing dogs with DMD to healthy controls

| Parameter | DMD | Control | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (BPM) | 170±39 | 111±20 | 0.01 |

| End-systolic Volume (ml) | 17.4±12.1 | 14.6±6.2 | 0.6 |

| End-diastolic Volume (ml) | 32.6±14.7 | 32.6±9.3 | 1.0 |

| Stroke volume (ml) | 15.1±4.5 | 18.0±3.5 | 0.3 |

| Cardiac Output (l/min) | 2.4±0.2 | 2.0±0.7 | 0.2 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 50.5±14.8 | 56.6±6.4 | 0.4 |

| (45.2±10.4*) | (0.06*) | ||

| LV Mass (g) | 46.5±9.8 | 46.9±12.8 | 0.8 |

With one influential outlier from the DMD group removed

Figure 1.

Examples of CINE images at end-diastole and end-systole from a dog with DMD with ejection fraction (EF) of 52.0% (a) and a normal control with EF 57.2% (b).

Perfusion analysis was successfully performed for all dogs with DMD and 5 (83%) healthy controls. In the one remaining healthy control, weak enhancement was observed within the chamber, but no measurable tissue enhancement was seen. This was attributed to partial failure of the injection and this dog was excluded from further analysis.

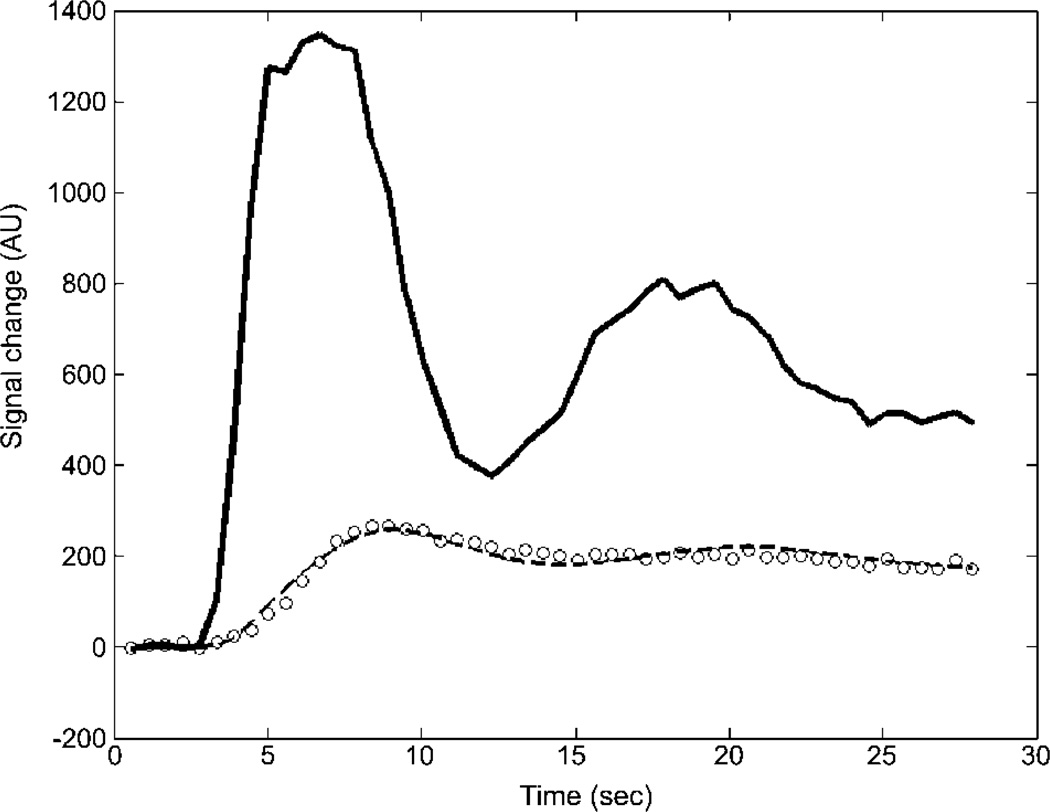

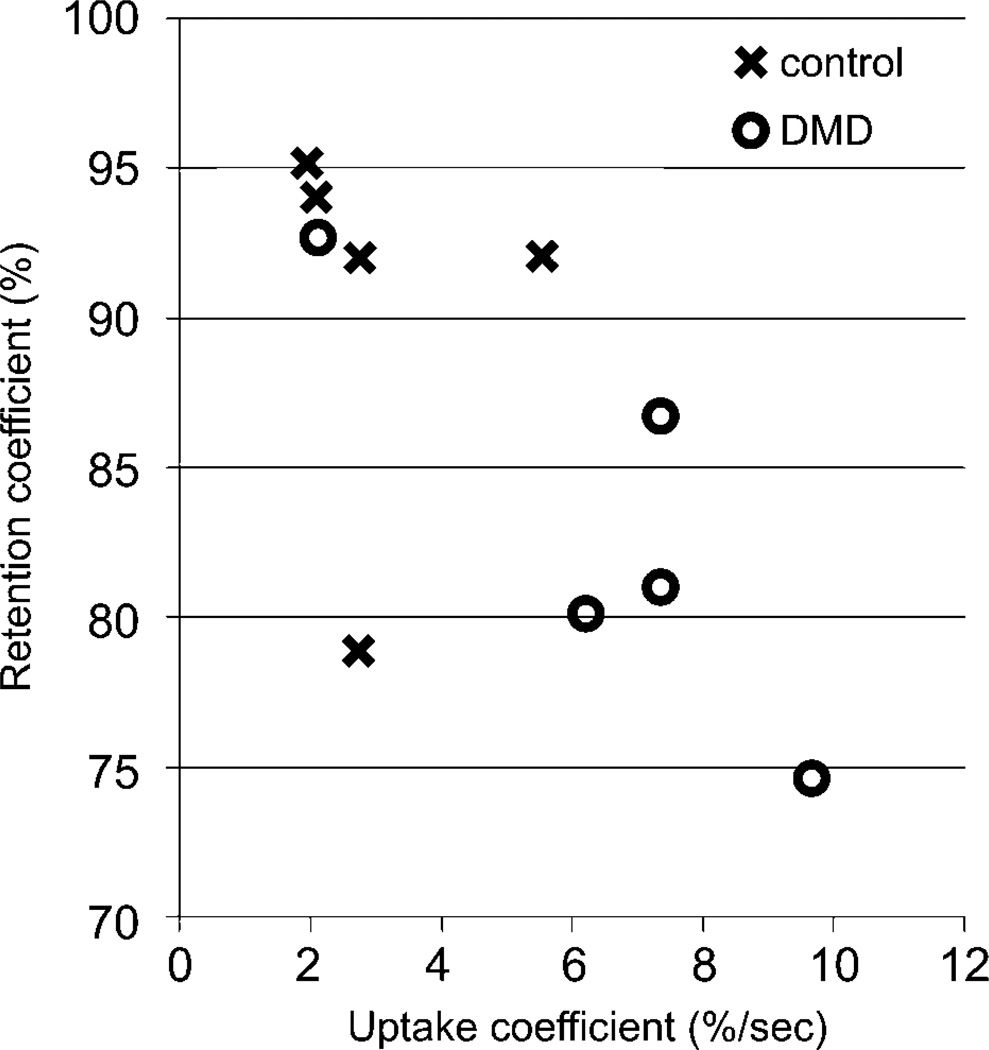

In the remaining dogs, visual evaluation confirmed that the automatic registration algorithm effectively eliminated translational motion due to breathing. The AIF extraction algorithm generated similar curves for all dogs, consisting of a fast-rising first peak followed by a second smaller peak due to bolus recirculation. The model produced qualitatively excellent fit results for the average myocardial enhancement curve (Figure 2). Average values of U1sec and R1sec for both groups are plotted in Figure 3. Dogs with DMD exhibited significantly higher uptake with mean U1sec (± standard deviation) of 6.76% (± 2.41%) compared to 2.98% (± 1.46%) in controls (p=0.03). Additionally, retention appeared lower with mean of R1sec 82.2% (± 5.8%) in dogs with DMD compared to 90.5% (± 6.6%) in controls (p=0.12).

Figure 2.

Example of model fit to average data from one dog with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The solid curve is the automatically extracted arterial input function (AIF) and the circles are data points measured in the myocardium of the left ventricle. The dashed curve shows the best model fit based on the AIF.

Figure 3.

Values of the uptake and retention coefficients measured in 5 dogs with DMD versus 5 healthy controls.

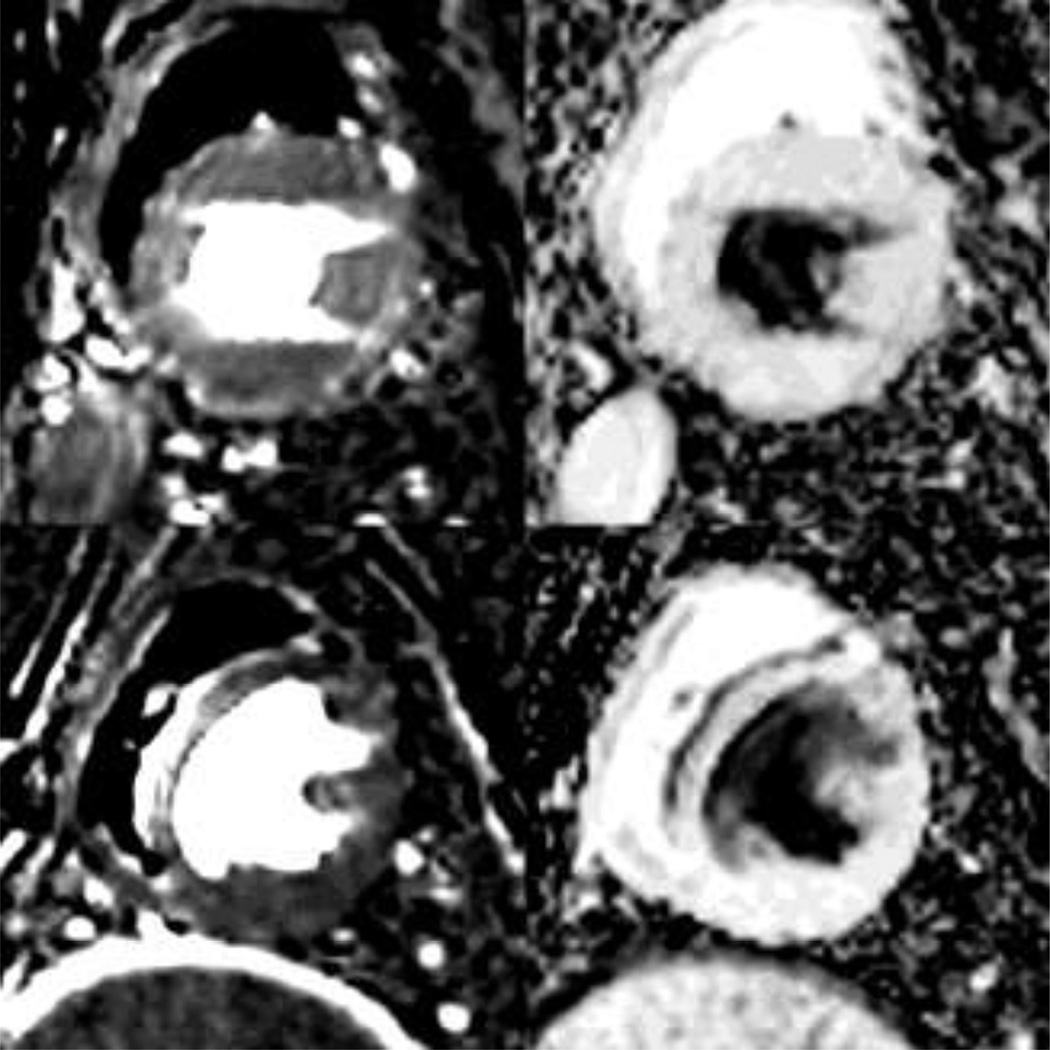

Representative perfusion maps of the uptake and retention coefficients are shown in Figure 4 for a dog with DMD and a healthy control. Maps of both U1sec and R1sec show fairly uniform values within the myocardium, which is easily distinguished from surrounding regions. These examples confirm on a pixel scale the observed tendency for higher uptake and reduced retention in dogs with DMD. We also observe that the left ventricle chamber is characterized by 100% uptake and 0% retention. The right ventricle chamber, on the other hand, exhibits a non-physical model result with 0% uptake and 100% retention. This is attributed to the time lag between bolus arrival in the right and left ventricles, which is not captured in the model.

Figure 4.

Parametric maps of the uptake coefficient (left) and retention coefficient (right) for a dog with DMD (top) and a health control (bottom).

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates the potential utility of a discrete approximation of the Kety model for quantitative perfusion analysis by CMRI. By parameterizing the model in terms of uptake and retention coefficients, perfusion maps are presented in an intuitive representation of the rates of wash-in and wash-out, respectively. Using this framework, the clinician can quickly assess whether abnormal contrast enhancement is due to altered delivery of the agent, increased retention of the agent, or both. On the other hand, a direct relationship exists between U1sec and R1sec and the kinetic parameters Ktrans, kep, MBF, EE, and λ.. This permits the discrete parameters to be translated into those more traditional physiological quantities.

The application of this technique to a study of DMD in dogs demonstrated its ability to reliably and automatically extract qualitative and quantitative representations of cardiac perfusion. Few prior studies of contrast agent uptake in DMD exist. A study in skeletal muscle in a mouse model found that early in the disease, enhanced perfusion is likely due to active degeneration/regeneration processes in muscle, with reduced perfusion in later stages of the disease [28]. In humans, a high prevalence of myocardial scar has been observed which typically is associated with perfusion deficits [14–16]. In this study, no myocardial scar was observed; however, it does not exclude ongoing inflammation or fibrosis. Because of the lack of scar and enhanced perfusion in dogs with DMD, our results are consistent with an early-stage disease model. If confirmed in further studies, this finding could have implications for studies relating perfusion responses to treatment in dogs versus humans.

A major motivation for this study was a desire to use this technique in the future to monitor changes in cardiac function over time for disease staging or monitoring therapy, first in the preclinical DMD dogs and then translating into human DMD patients. Whether myocardial perfusion transitions from a hyperperfused state to a hypoperfused state in later stages of DMD remains to be determined. In principle, the technique described here provides a robust, automated, and quantitative approach to address such questions.

In addition to investigating myocardial perfusion in DMD, this study also examined quantitative cardiac function based on cross-sectional CINE images. Reduced EF has been frequently observed in echocardiographic studies of DMD [29–31]. The results here indicated a trend toward reduced EF in dogs with DMD. We also observed elevated heart rates within the DMD group. One question that arises is whether the apparent changes in perfusion observed are a consequence or contributing cause of the altered functional parameters. Investigating this question will prove critical in determining which parameters are of most value for assessing cardiac involvement in DMD.

Regarding the discrete kinetic model implementation, insight can be gained by considering a hypothetical case in which the AIF rises to a concentration C for one time interval before returning to zero. In this case, the tissue concentration would rise to UC over the interval and then decay at a rate proportional to Rt. In actual situations, the contrast agent kinetics can be viewed as the superposition of such impulse responses due to the concentration in each interval [8]. From this, we see that two aspects of contrast agent dynamics are neglected in the model. First, changes in the AIF over the interval are not modeled, and second, the model does not account for any contrast agent that enters and leaves the tissue within the same interval. The impact of both of these assumptions is minimized by using short intervals, such as single heart beats. In this study, the interval was typically on the order of 0.5 sec.

In this study, we also explored two methods for fitting the model to the data. For producing parametric images, we used the linear solution of Equation 4, which could be rapidly computed for every pixel in the image. The results, however, were not as accurate as those from direct fitting of Equation 2 because the presence of tissue concentrations on both sides of Equation 4 can lead to numerical instabilities. The differences were not apparent when viewing parametric images, but for quantitative reporting, we chose to use non-linear fitting of Equation 2.

The major limitation for this study is its small size. In many cases, compelling trends were observed, such as the reduced retention coefficient in dogs with DMD, but did not achieve statistical significance. The small size also precluded multiparametric analyses to assess interactions between variables. Most notably, the influence of the larger distribution in ages of the dogs with DMD compared to the healthy controls was not assessed. Nevertheless, the small study size was sufficient to demonstrate the potential of this approach for future studies.

In conclusion, this study illustrates the potential utility of a discrete model of contrast agent kinetics to investigate myocardial perfusion characteristics. Model parameters describing uptake and retention of the contrast agent were automatically extracted in all cases on a pixel level. When applied to the study of DMD in dogs, the model was consistent with enhanced perfusion associated with the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Baocheng Chu and Jennifer Totman for technical assistance with MRI; A. Joslyn, E. Zellmer, Jennifer Duncan, DVM, M. Spector, DVM and their team for their care of the dogs. We further thank S. Carbonneau, H. Crawford, B. Larson, K. Carbonneau, J. Vermeulen, and D. Gayle for administrative assistance and manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH U54-HD47175; NIH R01-AR056949; and by a Career Development Grant (to Z. Wang) from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA 114979).

Contributor Information

William S. Kerwin, Email: bkerwin@u.washington.edu.

Anna Naumova, Email: nav@u.washington.edu.

Rainer Storb, Email: rstorb@fhcrc.org.

Stephen J. Tapscott, Email: stapscot@fhcrc.org.

Zejing Wang, Email: zwang@fhcrc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cury RC, Cattani CA, Gabure LA, Racy DJ, de Gois JM, Siebert U, Lima SS, Brady TJ. Diagnostic performance of stress perfusion and delayed-enhancement MR imaging in patients with coronary artery disease. Radiology. 2006;240:39–45. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401051161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingham SE, Hachamovitch R. Incremental prognostic significance of combined cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, adenosine stress perfusion, delayed enhancement, and left ventricular function over preimaging information for the prediction of adverse events. Circulation. 2011;123:1509–1518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.907659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korosoglou G, Elhmidi Y, Steen H, Schellberg D, Riedle N, Ahrens J, Lehrke S, Merten C, Lossnitzer D, Radeleff J, Zugck C, Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Prognostic value of high-dose dobutamine stress magnetic resonance imaging in 1,493 consecutive patients: assessment of myocardial wall motion and perfusion. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56:1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doesch C, Seeger A, Doering J, Herdeg C, Burgstahler C, Claussen CD, Gawaz M, Miller S, May AE. Risk stratification by adenosine stress cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with coronary artery stenoses of intermediate angiographic severity. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2009;2:424–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukiji M, Nguyen P, Narayan G, Hellinger J, Chan F, Herfkens R, Pauly JM, McConnell MV, Yang PC. Peri-infarct ischemia determined by cardiovascular magnetic resonance evaluation of myocardial viability and stress perfusion predicts future cardiovascular events in patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2006;8:773–779. doi: 10.1080/10976640600737615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selvanayagam JB, Jerosch-Herold M, Porto I, Sheridan D, Cheng AS, Petersen SE, Searle N, Channon KM, Banning AP, Neubauer S. Resting myocardial blood flow is impaired in hibernating myocardium: a magnetic resonance study of quantitative perfusion assessment. Circulation. 2005;112:3289–3296. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerber BL, Raman SV, Nayak K, Epstein FH, Ferreira P, Axel L, Kraitchman DL. Myocardial first-pass perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance: history, theory, and current state of the art (Review) Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2008;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerosch-Herold M. Quantification of myocardial perfusion by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (Review) Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2010;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyler KL. Origins and early descriptions of "Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Muscle & Nerve. 2003;28:402–422. doi: 10.1002/mus.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muntoni F, Torelli S, Ferlini A. Dystrophin and mutations: one gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes (Review) Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:731–740. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finsterer J, Stollberger C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies (Review) Cardiology. 2003;99:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000068446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan D. Challenges and opportunities in dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy gene therapy. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(Spec. No. 2):R253–R261. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoogerwaard EM, van der Wouw PA, Wilde AA, Bakker E, Ippel PF, Oosterwijk JC, Majoor-Krakauer DF, van Essen AJ, Leschot NJ, de Visser M. Cardiac involvement in carriers of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders. 1999;9:347–351. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(99)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva MC, Meira ZM, Gurgel GJ, da Silva MM, Campos AF, Barbosa MM, Starling Filho GM, Ferreira RA, Zatz M, Rochitte CE. Myocardial delayed enhancement by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with muscular dystrophy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49:1874–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puchalski MD, Williams RV, Askovich B, Sower CT, Hor KH, Su JT, Pack N, Dibella E, Gottliebson WM. Late gadolinium enhancement: precursor to cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy? The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2009;25:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9352-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilchick KC, Salerno M, Plitt D, Dori Y, Crawford TO, Drachman D, Thompson WR. Prevalence and distribution of regional scar in dysfunctional myocardial segments in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2011;13:20. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perloff JK, Henze E, Schelbert HR. Alterations in regional myocardial metabolism, perfusion, and wall motion in Duchenne muscular dystrophy studied by radionuclide imaging. Circulation. 1984;69:33–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura T, Yanagisawa A, Sakata H, Sakata K, Shimoyama K, Ishihara T, Yoshino H, Ishikawa K. Thallium-201 single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in patients with duchenne's progressive muscular dystrophy: a histopathologic correlation study. Japanese Circulation Journal. 2001;65:99–105. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelle S, Graf K, Dreysse S, Schnackenburg B, Fleck E, Klein C. Evaluation of contrast wash-in and peak enhancement in adenosine first pass perfusion CMR in patients post bypass surgery. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2010;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagel E, Klein C, Paetsch I, Hettwer S, Schnackenburg B, Wegscheider K, Fleck E. Magnetic resonance perfusion measurements for the noninvasive detection of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2003;108:432–437. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080915.35024.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diesbourg LD, Prato FS, Wisenberg G, Drost DJ, Marshall TP, Carroll SE, O'Neill B. Quantification of myocardial blood flow and extracellular volumes using a bolus injection of Gd-DTPA: kinetic modeling in canine ischemic disease. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1992;23:239–253. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pack NA, Dibella EV, Wilson BD, McGann CJ. Quantitative myocardial distribution volume from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;26:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Springer CS, Jr, Jerosch-Herold M. First-pass dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with extravasating contrast reagent: evidence for human myocardial capillary recruitment in adenosine-induced hyperemia. NMR in Biomedicine. 2009;22:148–157. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel PP, Koppenhafer SL, Scholz TD. Measurement of kinetic perfusion parameters of gadoteridol in intact myocardium: effects of ischemia/reperfusion and coronary vasodilation. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1995;13:799–806. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(95)00032-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentine BA, Cooper BJ, de Lahunta A, O'Quinn R, Blue JT. Canine X-linked muscular dystrophy. An animal model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: clinical studies. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1988;88:69–81. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerwin WS, Cai J, Yuan C. Noise and motion correction in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for analysis of atherosclerotic lesions. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2002;47:1211–1217. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerwin WS, Oikawa M, Yuan C, Jarvik GP, Hatsukami TS. MR imaging of adventitial vasa vasorum in carotid atherosclerosis. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;59:507–514. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad N, Welch I, Grange R, Hadway J, Dhanvantari S, Hill D, Lee TY, Hoffman LM. Use of imaging biomarkers to assess perfusion and glucose metabolism in the skeletal muscle of dystrophic mice. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2011;12:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melacini P, Vianello A, Villanova C, Fanin M, Miorin M, Angelini C, Dalla VS. Cardiac and respiratory involvement in advanced stage Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular Disorders. 1996;6:367–376. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(96)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanza GA, Dello RA, Giglio V, De Luca L, Messano L, Santini C, Ricci E, Damiani A, Fumagalli G, De Martino G, Mangiola F, Bellocci F. Impairment of cardiac autonomic function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: relationship to myocardial and respiratory function. American Heart Journal. 2001;141:808–812. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Bockel EA, Lind JS, Zijlstra JG, Wijkstra PJ, Meijer PM, van den Berg MP, Slart RH, Aarts LP, Tulleken JE. Cardiac assessment of patients with late stage Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2009;17:232–237. doi: 10.1007/BF03086253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]