Abstract

Recent studies have shown a positive correlation between brown adipose tissue (BAT) and bone mineral density (BMD). However, mechanisms underlying this relationship are unknown. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is an important regulator of stem cell differentiation promoting bone formation. IGF binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2) binds IGF-1 in the circulation and has been reported to inhibit bone formation in humans. IGF-1 is also a crucial regulator of brown adipocyte differentiation. We hypothesized that IGFBP-2 is a negative and IGF-1 a positive regulator of BAT-mediated osteoblastogenesis. We therefore investigated a cohort of 15 women (mean age 27.7±5.7 years): 5 with anorexia nervosa (AN) in whom IGF-1 levels were low due to starvation, 5 recovered AN (AN-R), and 5 women of normal weight. All subjects underwent assessment of cold-activated BAT by PET/CT, BMD of the spine, hip, femoral neck, and total body by DXA, thigh muscle area by MRI, IGF-1 and IGFBP-2. There was a positive correlation between BAT and BMD and an inverse association between IGFBP-2 and both BAT and BMD. There was no association between IGF-1 and BAT. We show for the first time that IGFBP-2 is a negative predictor of cold-induced BAT and BMD in young non-obese women, suggesting that IGFBP-2 may serve as a regulator of BAT-mediated osteoblastogenesis.

Keywords: brown adipose tissue (BAT), IGFBP-2, bone mineral density (BMD), anorexia nervosa (AN)

1. Introduction

We have previously demonstrated a positive association between brown adipose tissue (BAT) and bone mineral density (BMD) in young women with anorexia nervosa (AN), recovered AN (AN-R), and women of normal-weight (1). Two subsequent studies, one in adults and one in children, have confirmed a positive association between BAT and BMD (2, 3). Furthermore, studies in a mouse model of impaired brown adipogenesis have shown impaired thermoregulation and reduced weight, body fat, and BMD (4), suggesting a role of BAT in the regulation of bone formation. In addition, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 2 injection into mouse muscle triggered a brown adipocyte-generated hypoxic gradient leading to bone formation (5) and BMP7 has recently been identified as a promoter of BAT differentiation (6). However, there are no studies in humans examining potential mechanisms by which BAT may regulate bone formation.

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is an important regulator of stem cell differentiation, promoting bone formation (7–10). We have previously confirmed a positive association between IGF-1 and BMD and an inverse association with bone marrow fat in obese premenopausal women, supporting the role of IGF-1 as a regulator of the fat and bone lineage (11, 12). IGF binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2) binds IGF-1 in the circulation and in high concentrations has been found to inhibit IGF-1 action when added to osteoblastic cells in culture (13). Studies in mice lacking IGFBP-2 have shown impaired bone formation and suppression of bone turnover (14) suggesting that IGFBP-2 may have an effect on osteoblast recruitment and/or differentiation. However, studies in humans have revealed an inverse association between IGFBP-2 and BMD in aging men and women (15, 16). We have demonstrated a positive correlation between IGFBP-2 and bone marrow fat and an inverse association with BMD in women with AN (17), suggesting a role of IGFBP-2 in stem cell differentiation. The IGF-1 signaling pathway is also a crucial regulator of brown adipocyte differentiation in animals, and disruption of this pathway leads to defective thermogenesis (18–20).

The purpose of our study was to investigate the role IGFBP-2 and IGF-1 in the regulation of brown adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis in young women of normal weight, AN, and AN-R and determine predictors of BMD in this population. We hypothesized that IGFBP-2 is a negative and IGF-1 a positive regulator of BAT-mediated osteoblastogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was approved by Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the nature of the procedure had been fully explained. We studied 15 women with a mean age 27.7±5.7 years; 5 with AN, 5 recovered AN (AN-R), defined as > 85% of ideal body weight and having regular menstrual cycles for at least 3 months, and 5 healthy women of normal weight. Detailed subject characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and assessment of brown fat and BMD have been described previously (1). IGFBP-2 levels and the relationship between IGFBP-2, IGF-1 and BMD have not been previously published. As per study design, BMI of the AN group (18.3±0.9 kg/m2) was lower than that of AN-R (22.4±3.8 kg/m2) and normal weight groups (21.9±1.4 kg/m2) (p=0.04).

All subjects were examined at a single study visit at our Clinical Research Center. IGF-1 was measured by ISYS Multi-Discipline Automated Analyzer (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Inc., Fountain Hills, AZ) with a detection limit of 4.4 ng/ml, detection range of 10–1200 ng/ml, and an interassay variability of 5.1%. IGFBP-2 was measured by ELISA (Alpco, Mediagnost, Salem, NH) with a detection limit of 0.2 ng/ml, intra-assay variability of 5.5% and interassay variability of 3.7%.

2.1. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT)

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging was performed following a standardized 2 hour cooling procedure with subjects wearing a cooling vest (Polar Products Cool flow system, Polar Products, Stow, OH) as previously described (1). Briefly, whole body PET/CT (Biograph; Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, Pa) was performed one hour after the intravenous injection of 10 mCi (370 MBq) 18F-FDG. A low-dose CT scan (120kVp, 11–40 mAS) with 5mm slice thickness was performed for attenuation correction and anatomic localization. Semiquantitative and qualitative evaluation of PET images was performed and standardized uptake values (SUVs) were determined. The volume of BAT (ml) was quantified using OpenPACS and PET-CT Viewer shareware as previously described (21, 22).

2.2.MR imaging

Single axial MR imaging slice through the mid thigh was obtained (Siemens Trio, 3T, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) and thigh muscle area was determined (VITRAK, Merge/eFilm, WI).

2.3.Dual-energy X-ray-absorptiometry (DXA)

DXA was used to measure BMD using a Hologic QDR 4500 scanner (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA). The following parameters were obtained: BMD of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, hip and total body.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP software (version 9.0, SAS Institute, Carry, NC). Variables were tested for normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables that were not normally distributed were log transformed. Linear regression analysis of BAT and IGFBP-2 on BMD, IGF-1 and thigh muscle was performed. Multivariate standard least squares regression modeling was performed to control for IGF-1 levels and disease status. Stepwise regression modeling was used to determine predictors of BMD. P ≤ 0.05 was used to denote significance and p ≤ 0.1 was used to denote a trend.

3. Results

3.1.Clinical characteristics

Of the 15 women, seven were positive for BAT using FDG-PET and eight were negative for BAT. Within the AN group, 1 out of 5, in the AN-R group 2 out of 5, and in the HC group 4 out of 5 subjects were BAT positive. There was no significant difference in the amount of BAT between the three groups (p=0.2).

3.2. Predictors of bone mineral density

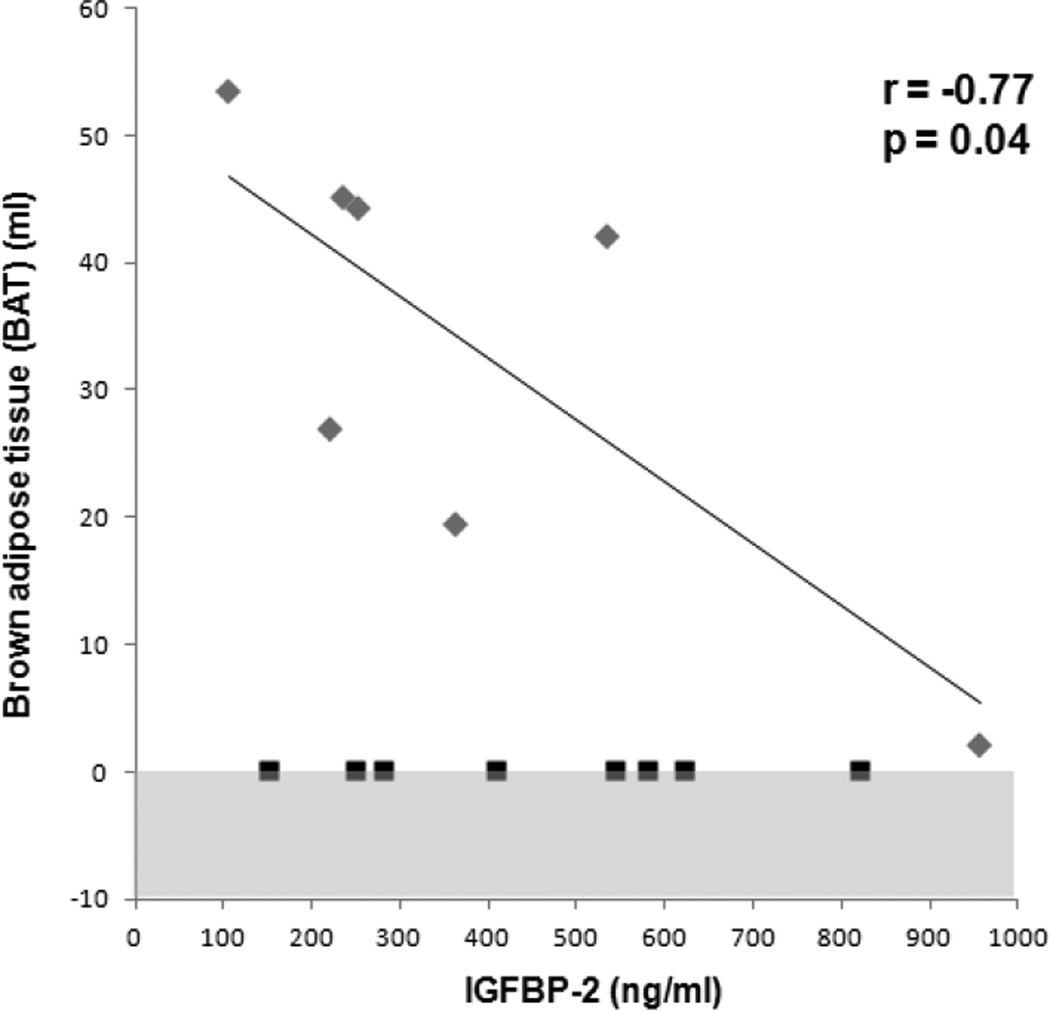

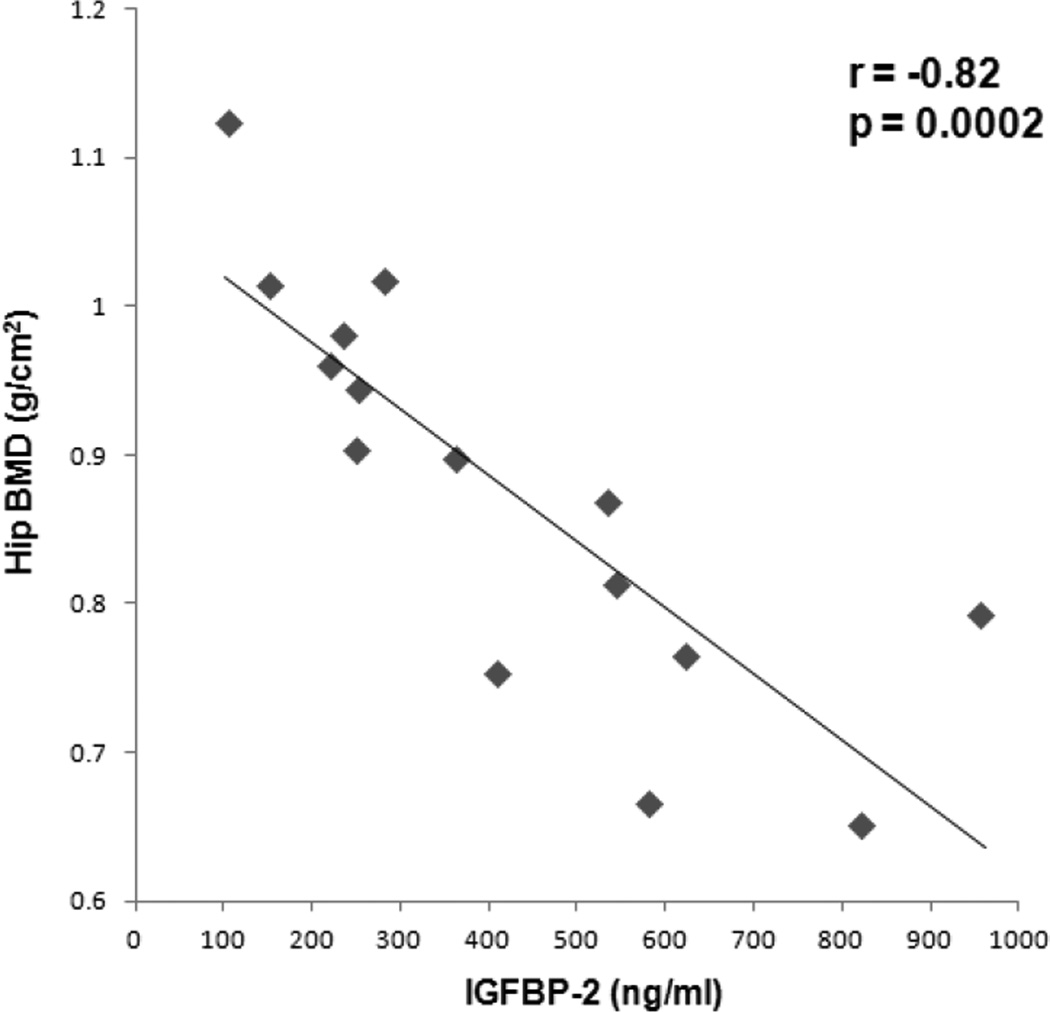

There was an inverse association between IGFBP-2 and BAT (r= −0.77, p=0.04), which remained significant after controlling for IGF-1 levels and disease status (p=0.04) (Figure 1). IGFBP-2 was inversely associated with BMD of the femoral neck (r= −0.89, p<0.0001), total hip (r= −0.82, p=0.0002) (Figure 2), lumbar spine (r= −0.62, p= 0.01), and total body (r= −0.50, p=0.06). The associations between IGFBP-2 and BMD of the femoral neck and total hip remained significant after controlling for IGF-1 levels and disease status (p=0.009 and p=0.01, respectively). The associations between IGFBP-2 and lumbar spine and total body BMD lost significance after controlling for IGF-1 levels and disease status (p=0.2 and p=0.6, respectively). There was a trend of an inverse association between IGF-1 and IGFBP-2 (r= −0.46, p=0.1). There was no correlation between BAT and IGF-1 in the BAT positive subjects (p=0.5) and combined BAT positive and negative subjects (p=0.8).

Figure 1.

Regression analysis of brown adipose tissue (BAT) on IGFBP-2. There was an inverse association between BAT and IGFBP-2 in subjects with detectable BAT. Grey diamonds: subjects with BAT, black squares: subjects without BAT. Shaded area represents undetectable range.

Figure 2.

Regression analysis of hip bone mineral density (BMD) on IGFBP-2. There was an inverse association between hip BMD and IGFBP-2.

Thigh muscle area correlated positively with femoral neck BMD (r=0.55, p=0.03), IGF-1 (r= 0.55, p=0.05) and inversely with IGFBP-2 (r= −0.50, p= 0.06).

As previously reported, there were positive correlations between BAT and BMD of the femoral neck, total hip, total body, and lumbar spine (r=0.58 to r=0.67, p=0.01 to p=0.02), which remained significant after controlling for BMI and disease status (p=0.04) (1).

When hip BMD was entered as a dependent variable and BAT, IGFBP-2, and muscle mass as independent variables in a forward stepwise regression model, only IGFBP-2 was a significant predictor of hip BMD and explained 76% (r-square = 0.76, p= 0.01) of the variability of total hip BMD.

When lumbar spine BMD was entered as a dependent variable in a forward stepwise regression model and BAT, IGFBP-2, and muscle mass as independent variables, only BAT was a significant predictor of hip BMD and explained 57% (r-square= 0.57, p=0.05) of the variability of lumbar spine BMD.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to show that IGFBP-2 is a negative predictor of BAT and BMD and BAT is a positive predictor of BMD in young normal weight women, women with AN and AN-R, independent of disease status and IGF-1 levels, suggesting that IGFBP-2 could be involved in the regulation of BAT-mediated osteoblastogenesis.

Recent studies in humans have suggested a positive effects of BAT on bone formation (1–3, 5, 6). In a study of young normal weight women, women with AN and AN-R, we have demonstrated increased BMD and lower levels of Pref-1 in subjects with BAT compared to subjects without BAT, suggesting that BAT may be involved in the regulation of stem cell differentiation (1). Ponrartana et al. examined PET/CT studies of children who had been treated successfully for malignancies and found positive correlations between BAT volume and femoral cross sectional area, cortical area as well as thigh muscle area (3). However, the contribution of muscle mass as a determinant of bone structure decreased the contribution of BAT, suggesting that the BAT-bone connection could be in part mediated by muscle. In our study, there was no association between BAT and muscle area. This may be due to the small number of subjects and the low range of muscle areas as all of our women were thin. There may also be differences in the BAT-muscle connection in children, who have larger volumes of BAT compared to the subjects in our study. Our findings are concordant with a study by Lee et al, that found higher BMD in adult men and women with positive BAT but no association between BAT and lean mass (2). No studies in humans have investigated hormonal determinants of BAT-mediated bone formation.

IGF-1 has been identified as an important regulator of stem cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage (7, 9–12) and recent studies in animals have established IGF-1 as an important regulator of brown adipocyte differentiation (18–20). In the current study, there was no association between BAT and IGF-1. A potential explanation may be that IGF-1 levels are low in patients with AN. IGFBP-2 is a binding protein that binds IGF-1 in the circulation and is expressed in most tissues, including the skeleton (23). Studies in aging men and women have shown an inverse association between IGFBP-2 and BMD (15, 16). We have previously demonstrated a positive correlation between IGFBP-2 and bone marrow fat and an inverse association with BMD in women with AN (17). In contrast, mice with deletion of the IGFBP-2 gene, exhibit suppression of bone turnover due to impaired osteoclastogenesis, but without an increase in marrow adiposity despite very low bone mass. These data indicate that IGFBP-2 is important for bone acquisition and may modulate marrow adiposity as well (14). In our study, there were strong IGF-1- independent inverse associations between IGFBP-2 and BAT and IGFBP-2 and BMD at various sites, suggesting that IGFBP-2 may be a mediator of BAT-induced bone formation in humans.

Our study had several limitations. First is our small sample size. However, with only 7 BAT positive women we were able to find significant associations between BAT and IGFBP-2 and BMD. Second, our study group was heterogeneous and was comprised of women with AN, AN-R, and normal weight. We therefore controlled for disease status using multivariate standard least squares regression modeling.

In conclusion, BAT is a positive predictor of BMD and IGFBP-2 is an IGF-1-independent negative predictor of both BMD and BAT in young thin women. Our data suggest that IGFBP-2 may serve as a regulator of BAT-mediated osteoblastogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R24 DK084970 and UL1 RR025758

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Freedman LM, Calder G, Lee H, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. Young women with cold-activated brown adipose tissue have higher bone mineral density and lower Pref-1 than women without brown adipose tissue: a study in women with anorexia nervosa, women recovered from anorexia nervosa, and normal-weight women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E584–E590. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee P, Brychta RJ, Collins MT, Linderman J, Smith S, Herscovitch P, Millo C, Chen KY, Celi FS. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue is an independent predictor of higher bone mineral density in women. Osteoporos Int. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2110-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponrartana S, Aggabao PC, Hu HH, Aldrovandi GM, Wren TA, Gilsanz V. Brown adipose tissue and its relationship to bone structure in pediatric patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2693–2698. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanotti S, Stadmeyer L, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Durant D, Canalis E. Misexpression of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta causes osteopenia. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:263–274. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olmsted-Davis E, Gannon FH, Ozen M, Ittmann MM, Gugala Z, Hipp JA, Moran KM, Fouletier-Dilling CM, Schumara-Martin S, Lindsey RW, Heggeness MH, Brenner MK, Davis AR. Hypoxic adipocytes pattern early heterotopic bone formation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:620–632. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng YH, Kokkotou E, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Winnay JN, Taniguchi CM, Tran TT, Suzuki R, Espinoza DO, Yamamoto Y, Ahrens MJ, Dudley AT, Norris AW, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature. 2008;454:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/nature07221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett A, Chen T, Feldman D, Hintz RL, Rosenfeld RG. Characterization of insulin-like growth factor I receptors on cultured rat bone cells: regulation of receptor concentration by glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1577–1583. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Canalis E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:535–559. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hock JM, Centrella M, Canalis E. Insulin-like growth factor I has independent effects on bone matrix formation and cell replication. Endocrinology. 1988;122:254–260. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-1-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen CJ, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Adamo ML, Shultz KL, Rubin J, Donahue LR, Horton LG, Delahunty KM, Beamer WG, Sipos J, Clemmons D, Nelson T, Bouxsein ML, Horowitz M. Congenic mice with low serum IGF-I have increased body, fat reduced bone mineral density, and an altered osteoblast differentiation program. Bone. 2004;35:1046–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Harrington LM, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Miller KK. Determinants of bone mineral density in obese premenopausal women. Bone. 2011;48:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Vertebral Bone Marrow Fat Is Positively Associated With Visceral Fat and Inversely Associated With IGF-1 in Obese Women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feyen JH, Evans DB, Binkert C, Heinrich GF, Geisse S, Kocher HP. Recombinant human [Cys281]insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 inhibits both basal and insulin-like growth factor I-stimulated proliferation and collagen synthesis in fetal rat calvariae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19469–19474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMambro VE, Maile L, Wai C, Kawai M, Cascella T, Rosen CJ, Clemmons D. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 is required for osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:390–400. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin S, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Khosla S. A potentially deleterious role of IGFBP-2 on bone density in aging men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1075–1083. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto T, Nishiyama K, Kuribayashi F, Chihara K. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-2, and IGFBP-3 in osteoporotic patients with and without spinal fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1272–1279. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.8.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR, Breggia A, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:407–413. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boucher J, Mori MA, Lee KY, Smyth G, Liew CW, Macotela Y, Rourk M, Bluher M, Russell SJ, Kahn CR. Impaired thermogenesis and adipose tissue development in mice with fat-specific disruption of insulin and IGF-1 signalling. Nat Commun. 2012;3:902. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cypess AM, Zhang H, Schulz TJ, Huang TL, Espinoza DO, Kristiansen K, Unterman TG, Tseng YH. Insulin/IGF-I regulation of necdin and brown adipocyte differentiation via CREB- and FoxO1-associated pathways. Endocrinology. 2011;152:3680–3689. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng YH, Butte AJ, Kokkotou E, Yechoor VK, Taniguchi CM, Kriauciunas KM, Cypess AM, Niinobe M, Yoshikawa K, Patti ME, Kahn CR. Prediction of preadipocyte differentiation by gene expression reveals role of insulin receptor substrates and necdin. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:601–611. doi: 10.1038/ncb1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbaras L, Tal I, Palmer MR, Parker JA, Kolodny GM. Shareware program for nuclear medicine and PET/CT PACS display and processing. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W565–W568. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]