Abstract

Objective

Mutations in SCN9A have been reported in (1) congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP); (2) primary erythromelalgia; (3) paroxysmal extreme pain disorder; (4) febrile seizures and recently (5) small fibre sensory neuropathy. We sought to investigate for SCN9A mutations in a clinically well-characterised cohort of patients with CIP and erythromelalgia.

Methods

We sequenced all exons of SCN9A in 19 clinically well-studied cases including 6 CIP and 13 erythromelalgia (9 with family history, 10 with small-fibre neuropathy). The identified variants were assessed in dbSNP135, 1K genome, NHLBI-Exome Sequencing Project (5400-exomes) databases, and 768 normal chromosomes.

Results

In erythromelalgia case 7, we identified a novel Q10>K mutation. In CIP case 6, we identified a novel, de novo splicing mutation (IVS8-2A>G); this splicing mutation compounded with a nonsense mutation (R523>X) and abolished SCN9A mRNA expression almost completely compared with his unaffected father. In CIP case 5, we found a variant (P610>T) previously considered causal for erythromelalgia, supporting recently raised doubt on its causal nature. We also found a splicing junction variant (IVS24-7delGTTT) in all 19 patients, this splicing variant was previously considered casual for CIP, but IVS24-7delGTTT was in fact the major allele in Caucasian populations.

Conclusions

Two novel SCN9A mutations were identified, but frequently polymorphism variants are found which may provide susceptibility factors in pain modulation. CIP and erythromelalgia are defined as genetically heterogeneous, and some SCN9A variants previously considered causal may only be modifying factors.

Keywords: Pain, Neurogenetics

Introduction

The sensation of pain provides a crucial protective mechanism. The loss of pain sensation or exaggerated pain has serious consequences in health. Inherited erythromelalgia (IEM) is characterised by attacks of red, painful extremities, and small fibre neuropathy has been documented.1–3 By contrast, patients with congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP) can feel stimulus, but do not perceive them as painful or noxious even with bone fractures, cuts, burns or corneal abrasions. CIP is distinguished from patients with ‘indifference to pain’ where there is an asymbolia to pain on the basis of central emotional neglect which can occur in schizophrenia, pervasive developmental delay and psychosis with catatonia.4

Previous studies identified mutations of voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.7 gene (SCN9A) in both CIP and IEM.5 6 SCN9A belongs to a family of nine sodium channel α subunits (Nav1.1-Nav1.9).7 They all share an important characteristic of transporting positively charged sodium ions, playing a key role in generating and transmitting electrical signals. Each subunit exhibits a specialised function and distinct expression pattern. Nav1.8 is mainly expressed by A- and c-fibres important in nociception, Nav1.9 is selective for a subset of c-fibres, while Nav1.7 (SCN9A) is universally expressed in all sensory neurones and recognised as a key molecule involved in peripheral pain processing.8 SCN9A mutations have now been linked with a diverse group of disorders beyond CIP and erythromelalgia,9 including paroxysmal extreme pain disorder,10 seizures11 and most recently idiopathic small-fibre neuropathy. 12 13 In patients with IEM, gain-of-function SCN9A heterozygous mutations are found enhancing channel activity; while in patients with CIP, loss-of-function SCN9A mutations are found attenuating channel activities. Anosmia (inability to sense smell) has also been reported in patients with CIP,14 and animal studies support the role of SCN9A in olfaction.15 Despite a large number of SCN9A mutations being reported in this highly polymorphic gene,16 how frequently these mutations occur in these disorders is mostly unknown.16

In this report, we genetically analysed SCN9A in 19 indexed patients who have either CIP or IEM (6 CIP and 13 erythromelalgia) with or without evidence of small fibre sensory loss. The neurological and genetic abnormalities of these patients were characterised using various clinical tests, web-based SNP database, and DNA sequence of normal controls.

Methods

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Mayo Clinic, and all patients were consented for participation. Utilising our electronic medical record retrieval system, we searched for patients with CIP or erythromelalgia whose transformed lymphoblast cell lines are available for DNA extraction. Standard techniques for DNA Sanger sequencing were performed to sequence the 26 coding exons of SCN9A including 30 bp of flanking intron sequence (primer sequences are available upon request). We assessed the identified variants in dbSNP135, 1K genome and NHLBI-Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) (5400-exomes) databases, also screened 768 normal chromosomes for novel mutations. Our normal controls have northern European ancestry, and were clinically examined by neurologists at Mayo Clinic, assessed by nerve conductions and quantitative sensory testing over many years as part of the Rochester Diabetic Study Controls.17

Patients with CIP

All patients with CIP patients had dramatic histories of recurrent self-injurious events dating back to infancy or childhood without behavioural or cognitive explanation, that is, not ‘indifferent to pain’.18 None were from families with known consanguinity, and had no other family members affected. Bone fractures, joint dislocations, burns, corneal abrasions were all reported without pain. For all CIP diagnosis, we performed conventional histopathologic review of sensory nerves, including skin biopsy stained with PGP9.5, or detailed morphometric analysis of whole sensory nerve biopsies. Each affected CIP person was able to identify pain as a unique sensation, but had no withdrawal response to noxious stimulus including hot-plate testing to 45°C. CIP case 4 used her condition to garnish attention. She would dislocate her hips, place pencils through her flesh. Over time, most adult patients learned to avoid injury by using other cues beyond pain. They, nevertheless, did have occasional major mishaps, most commonly burns, crush or puncture injuries. One adult CIP patient (CIP case 2) jammed his hand in a car door but failed to realise the situation, he pulled his arm, nonetheless, leading to disfiguring injury.

Patients with erythromelalgia

All patients with erythromelalgia were selected based on the clinical definition and had paroxysmal extremity painful burning sensation associated with redness and increased heat of the skin.2 Detailed clinical descriptions and laboratory testing were reviewed in exclusion of other neurologic cause. Erythromelalgia evaluations included vascular studies with laser Doppler, thermoregulatory sweat test (TST), and autonomic reflex screens (ARS) with quantitative sudomotor autonomic reflex testing (QSART). Each patient had multiple tests for primary metabolic, inflammatory immune or haematologic derangements, including HGBA1c or fasting glucose, complete blood count (CBC) with differential, antinuclear antigen (ANA), extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), rheumatoid factor, CRP and many others. Family history of erythromelalgia (EM), or absence of discoverable family history (adopted status, or by family discord), was required. Reduced small fibre function by autonomic testing (quantitative sensory testing, ARS, TST) was also assessed.

Specialised physiologic clinical testing

Quantitative sensation testing to assess somatic sensory fibres (α-vibration, a-δ-cooling, c-heat pain) was utilised. The magnitude of detectable stimulus is expressed as a percentile of the measurement established from a normal population of persons of the same age and sex. Insensitivity for each modality is judged when showing ≥95th percentile or hyperalgesia when showing ≤5th percentile.19 ARS was utilised to assess a set of autonomic functions for severity of involvements and distribution of sudomotor, cardiovagal and adrenergic deficits. Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART) measures only the integrity of the postganglionic sudomotor axon's contribution to the sweat response.20 TST is a quantitative measure of total body sweating.21 It assesses the integrity of sudomotor pathways involved in the thermoregulatory response to environmental temperature, also provides the distribution of sweat loss and measurement of anterior body surface anhidrosis. TST also helps in establishing the site of lesion relative to the autonomic ganglia (preganglionic vs postganglionic) when combined with QSART. TST was conducted in a sweat cabinet (43–46°C air temperature, 35–40% relative humidity). Average skin temperature was kept between 38.5°C and 39.5°C. Sweating is demonstrated by a change in colour of an indicator powder applied on the surface of a patient lying in a sweat cabinet. Laser Doppler studies measured microvessel flow with elevations in heat-elevated regions typical of erythromelalgia.2

Results

Neurologic testing in 19 identified patients

We identified 19 indexed patients with either CIP (n=6) or erythromelalgia (n=13). All patients had been evaluated by specialists in peripheral nerve disease and/or dermatology with expertise in CIP and erythromelalgia. All patients had normal comprehensive nerve conductions (motor and sensory, upper and lower extremities) and needle electromyography studies in exclusion of a large-fibre peripheral neuropathy.

All six patients with CIP disorder had either sural nerve biopsy (n=5) or skin biopsy stained by PGP9.5 (n=1). The 5 patients with CIP who underwent sural nerve biopsy had epoxy-embedded preparations for electron microscopy and c-and a-δ nerve-fibre analysis. A histopathologic interstitial abnormality was not found among the six patients with CIP. One CIP patient (CIP case 4) was the subject of an earlier detailed clinical report, but had not been evaluated by SCN9A sequencing.22 She had reductions of a-δ fibres, while the remaining five cases had no fibre loss compared with age-matched controls.

Nine of 13 EM persons had documental family history with at least one first-degree relative having been affected (2–6 family members affected). All but three of the 13 patients with erythromelalgia had evidence of small nerve fibre function loss by TST, QSART and quantitative sensory testing. A summary of their clinical characteristics and electrophysiological findings are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and genetic summary of congenital insensitivity to pain and erythromelalgia cases

| Case | Onset | Sex | Family history | SCN9A mutation | EMG† | QST‡ for heat pain | Laser doppler tested§ | TST¶ or ARS†† anhidrosis | Nerve biopsy‡‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Infancy | M | No | Nl | >99% | No | Nl | Yes | |

| #2 | Infancy | M | No | Nl | >99% | No | Nl | Yes | |

| #3 | Infancy | F | No | Nl | >99% | No | Nl | Yes | |

| #4 | Infancy | M | No | Nl | >99% | No | Nl | Yes | |

| #5 | Infancy | F | No | Nl | No | No | Nl | Yes | |

| #6 | Infancy | M | No | *R523>X, IVS8-2A>G, K655>R | Nl | No | No | No | Yes |

| Erythromelalgia | |||||||||

| #1 | Twenty | F | Yes | Nl | <1% | Yes | Global | No | |

| #2 | Teens | F | Yes | Nl | >99% | Yes | Nl | No | |

| #3 | Teens | F | No | Nl | <1% | No | Regional | No | |

| #4 | Sixties | F | No | Nl | No | No | No | No | |

| #5 | Teens | F | Yes | Nl | No | Yes | Nl | No | |

| #6 | Teens | F | No | Nl | No | Yes | Regional | Yes | |

| #7 | Thirties | F | Yes | Q10K* | Nl | No | No | No | No |

| #8 | Teens | F | No | Nl | Nl | Yes | Regional | No | |

| #9 | Sixties | F | Yes | Nl | >99% | Yes | Nl | No | |

| #10 | Infancy | M | Yes | Nl | No | Yes | Regional | No | |

| #11 | Forties | F | Yes | Nl | Nl | Yes | Regional | No | |

| #12 | Fifties | F | Yes | Nl | No | Yes | Regional | No | |

| #13 | Teens | F | Yes | Nl | >99% | Yes | Regional | No | |

*Novel mutant variants.

†EMG is electromyography and inclusive of sural and median sensory, peroneal, tibial and ulnar motor nerve conduction studies.

‡QST is quantitative sensory testing that measures heat pain recognition where >95% represents insensitivity and <5% hyperalgesia compared with matched age and gender controls.19

§Erythromelalgia laser Doppler-tested patients who had findings consistent with erythromelalgia by having elevated skin temperature and blood flow at symptomatic distal extremities.2 3

¶TST is thermoregulatory sweat test with regions of anhidrosis noted.38

††ARS is autonomic reflex screen with abnormalities limited to sudomotor sweat function loss by quantitative sudomotor reflex testing with regions of anhidrosis noted.38

‡‡All congenital insensitivity to pain patients had whole sural nerve biopsy studied with normal sensory fibre evaluation apart from CIP index case #6 who had skin biopsy nerve studied by PGP9.5 immunostaining.

CIP, congenital insensitivity to pain; Nl, tested and normal; QST, quantitative sensation testing.

Novel SCN9A genetic findings

Of the 19 indexed cases (6 CIP and 13 erythromelalgia), 1 CIP and 1 erythromelalgia had what appeared to be novel mutations. Their detailed genetic and clinical phenotypes are described below.

CIP case 6

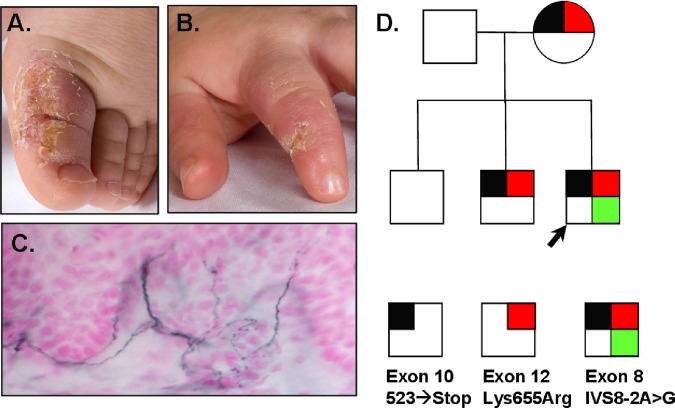

This otherwise developmentally normal 3-year-old toddler had insensitivity to pain. The disorder was first recognised when he started growing teeth and he would bite his lips and extremities to ulceration (figure 1). His parents wrapped the hands and feet to prevent injury, and arranged for continual surveillance to prevent major injuries. He frequently had major injuries including both at the head and extremities with major insults without crying, which was different from his two older brothers who have normal pain sensation. He now wears a safety helmet and requires constant care to avoid major injuries. His nerve conductions were normal, including the sural sensory amplitude of 22 uV. He did not cry or appear distressed during the nerve conduction study. On skin biopsy, he had a normal small fibre nerve density by PGP9.5 immunostaining with 7.84 fibres/mm with calculated 95%CI (6.83 to 8.95 fibres/mm) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Healing, painless mutilating injuries on the extremities (A, B) of a 3-year-old boy with CIP (case 6) who has normal sensory nerve conductions, needle EMG and skin small c-fibre density by PGP9.5 immunostaining (C). Family pedigree (D) of this patient with compound heterozygous mutation (R523>X, K655>R) of SCN9A including de novo splicing mutation IVS8-2A>G not found in his unaffected siblings or parents. EMG, electromyography.

Direct DNA sequencing identified a heterozygous splicing mutation at intron 8/exon 9 junction (IVS8-2A>G). The patient is the only one in his family who has this splicing mutation, none of his family members carried it, indicating a de novo mutation (figure 1). The mutation was not present in dbSNP135 database, 1K-genome database or NHLBI-ESP database. Additionally, we screened 768 chromosomes from our normal controls and confirmed its absence. The patient also had a heterozygous nonsense mutation at exon 11, R523>X, this mutation in homozygous state was previously reported as casual in patient with CIP.23 Our patient's mother and one sibling (sibling 1) carried heterozygous R523>X, but they appear normal with no apparent deficit in nociception. Interestingly, another heterozygous mutation K655>R in exon 13 was also found in the patient and his mother, as well as the same sibling with R523X. Heterozygous mutation K655>R was previously found as causal for febrile seizures.11 Since the patient's father was negative for all mutations, it is expected that the patient and one sibling inherited the allele containing R523X and K655>R from the mother. It is likely that R523X played an unexpectedly protective role in the mother and the one sibling, since neither of them has seizure disorder.

Since CIP case 6 has a nonsense mutation inherited from his mother on one allele, and has a de novo splicing mutation at the acceptor consensus site of exon 9 on the other allele, the mRNA from both alleles is likely to be prematurely degraded, causing the absence of functional SCN9A product—similar to the effect of a homozygous nonsense mutation. To confirm the detrimental effect of two compound heterozygous mutations, we used TaqMan expression assay to examine the SCN9A expression level. The total RNA samples were collected from CIP case 6 and his first-degree family members. The TaqMan assay probe was selected to hybridise across the junction of exon 18-exon 19 of SCN9A cDNA, so that the full length mRNA expression level can be examined. The result indicated that the patient has almost no detectable transcript compared with his father who did not carry any mutation, while his mother and the sibling 1 showed ∼50% of mRNA level. This confirmed that the loss of SCN9A protein is the cause for CIP case 6, indicating that there is a threshold of SCN9A level for causing CIP phenotype, since normal pain sensation was observed in CIP case 6's mother and sibling 1 despite their having the reduced SCN9A transcript level.

Erythromelalgia case 7

The patient is a 36-year-old woman, previously healthy, with a 12-month history of episodic foot burning pain, swelling, superficial venous dilatation, and increased local skin temperature, with redness affecting both feet. Attacks were reliably precipitated by leg dependence, prolonged standing, exercise or increase in body temperature, and initially relieved by cooling or elevation. Clinical examination and nerve conduction studies revealed no features of an underlying neuropathy. Haematological parameters were normal. Appropriate imaging of brain, spine and peripheral vasculature were normal. Symptoms were refractory to extensive therapeutic trials including aspirin, nortriptyline, gabapentin, carbamazepine, mexiletine, clonidine, topical lidocaine and lacosamide. The rapidity of symptom onset with dependence increased over time interfering with walking. The patient developed additional episodes of spontaneous non-painful cutaneous flushing affecting various body regions. There were no other autonomic derangements. Family history was notable for a diagnosis of chronic immune demyelinating neuropathy in her father which came years after having had burning feet from mid-late adulthood. The details of her clinical examinations were not available. The sequencing results showed that erythromelalgia case 7 has Q10K heterozygous mutation in exon 2. Previous study has identified SCN9A Q10R as causal in a patient with erythromelalgia with clinical onset in the second decade.24 Both Q10R and Q10K are absent in dbSNP135, 1K-genome, NHLBI ESP database, and 768 chromosomes of our normal controls.

Variants identified previously considered pathogenic

Splicing deletion mutation IVS24-7GTTT (RS77944059)

A splicing deletion mutation IVS24-7delGTTT was previously reported to cause CIP when compounded with a heterozygous stop-gain mutation (p.Glu693X).14 We found IVS24-7delGTTT in all 19 indexed patients, with homozygous in three CIP and all 13 erythromelalgia patients, and heterozygous in the other three patients with CIP. The allele frequencies of this variant are unknown in the dbSNP135 and NHLBI ESP databases. We screened 384 chromosomes using our normal controls, and found IVS24-7delGTTT was, in fact, the major allele (95%). Based on our results, three patients with CIP with heterozygous variant should be noted as IVS24-7het_InsGTTT with minor allele frequency of 5%. It is unlikely that IVS24-7GTTT variant contributed to CIP significantly.

P610>T (rs41268673)

The SCN9A variant P610>T was initially reported as a causal mutation for erythromelalgia.25 However, a recent study raised doubts on its disease-causal feature.26 We found P610>T in our CIP case 5, also in her unaffected family member. Additionally, P610>T has 2% minor allele frequency (MAF) in 1K-genome and NHLBI ESP database.

R1150>W (rs6746030)

The variant R1150>W was initially identified as causal mutation for primary erythromelalgia, but was subsequently found to have minor allele (T) frequency of 10% and is no longer considered as a causal mutation. Interestingly, a recent study indicated that the minor allele of R1150>W was significantly associated with the increased pain perception.27 We did not find any of our patients with erythromelalgia with this polymorphism, but two of our six patients with CIP carried its minor allele, which is conflicting with the notion of increased pain sensation. Our cohort is not large enough for association study, but our results emphasised the complexity of the genetic factors involved in the pain-related disorders, and the pain perception-altering mechanism of R>1150W needs further investigation.

Discussion

SCN9A encodes the α subunit of Nav1.7 and is important in nociception signalling function. It is highly expressed in the peripheral nervous system, including dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurones and sympathetic ganglion neurones.28 Seventeen out of our 19 indexed patients with either CIP or IEM did not have SCN9A mutations. We identified two novel mutations: (1) A de novo, novel splicing mutation IVS8-2A>G was identified in CIP case 6. This novel splicing mutation compounded with a heterozygous nonsense mutation, which leads to significantly reduced SCN9A expression. The identification of the de novo splicing mutation expands the spectrum of SCN9A gene abnormality associated with CIP phenotype. In total, 19 mutations have been linked to CIP disorder, four of them are homozygous missense mutations, nine are nonsense mutations, and the rest are small deletion/insertions which lead to either frame shift or premature stop codons, causing truncated transcript subjected to mRNA early decay or protein degradation.16 (2) Novel Q10K heterozygous mutation was identified in IEM case 7. Previous study24 identified a Q10R mutation as causal for erythromelalgia, and demonstrated that Q10R is associated with a smaller degree of DRG neurone excitability and later onset of phenotype. Arginine and lysine are both hydrophilic amino acids, and Q10K in erythromelalgia case 7 appeared to have similar effects as Q10R. Erythromelalgia case 7 had late onset at the age of 36 years, and her father did not have any symptom until mid-late adulthood. Our findings support a previous study that the mutations at Q1024 are linked with late onset age, emphasising that different SCN9A mutation, or polymorphism, has varied impact on nociception.

The large number of variants identified in SCN9A, and its association with various pain-related phenotypes, have made SCN9A a focus in pain-related disorders. However, our study suggests the pathogenic cause for a large percentage of patients with CIP and IEM with pain sensitivity disorders remains to be determined. SCN9A is composed of 1977 amino acids with 26 coding exons. It is a highly polymorphic gene, with more than 130 coding non-synonymous variants having been reported in several web-based variant databases, and 73 mutations have been associated with various clinical phenotypes in Human Genome Mutation Database.16 Recently, a large number of exomes have been sequenced, and more polymorphisms have been recognised in the human genome.29

Some SCN9A variants that were considered causal have now been found having greater than 1% allele frequencies (considered as polymorphisms), and appeared in persons without any phenotypes, suggesting a more complicated phenotype-genotype correlation involving other factors, including possible acquired pathogenic component. We found some patients in our cohort had variants previously considered causal, but without the associated phenotypes. Specifically, P610>T25 was initially reported as causal for erythromelalgia, but a recent study has suggested that P610T may only modify the phenotype in the proband.26 P610T is also showing 2% minor allele frequency in current SNP database. We identified P610>T in CIP case 5 and in her unaffected family member, indicating it is just a polymorphism of SCN9A. A splicing junction mutation IVS24-7delGTTT was previously reported to cause CIP when compounded with a stop-gain insertion mutation (p.Glu693X),14 but we found IVS24-7DelGTTT in all 19 indexed patients. Through screening 384 chromosomes of normal controls, we realised that IVS24-7delGTTT was, in fact, the major allele with a frequency of 95%.

Rare polymorphisms of SCN9A may have clinical modifying significance. It has been suggested that even a small impact on the channel function can contribute to the pain-related disorders.12 SCN9A polymorphism rs6754031 has been linked with severe fibromyalgia,30 and rs6746030 (R1150>W) was found significantly associated with increased pain perception.27 A recent study identified eight SCN9A mutations among 28% of 28 patients with biopsy confirmed idiopathic small-fibre neuropathy(I-SFN).13 These studies expanded the clinical implication of SCN9A and provided a new potentially exciting aspect in understanding of SCN9A channel function. However, the penetrance and the expressivity of these mutations may vary among different individuals and are likely influenced by other factors since many of these discovered mutations are present in 1000 genome or NHLBI ESP database. Also, many of these reported mutations have not yet been confirmed to track with the phenotype in families due to lack of family history information.13 It is conceivable to believe that certain SCN9A variants exert smaller effects on the channel function, and contribute to the variation of nociception and pain susceptibility among the population, while more detrimental SCN9A mutations can severely affect the channel's function with strong family histories with erythromelalgia or CIP. Why small fibre sensory nerves would undergo degeneration by the mechanism of hyperexcitable voltage-gated Na+ channels is not clear. However, previous studies showed Na+ influx imposes an energetic load on neurones and neuronal processes,31 and it was postulated that axonal degeneration may be resulted from intracellular Ca++ overload as a result of continued influx of Na+.32

Despite a large number of SCN9A mutations that were found in pain-related disorders, our study suggests the mutation frequency in CIP and erythromelalgia is low, and the pathogenic cause for the majority of the patients remains to be discovered. Accurate clinical diagnosis for diverse causes of pain disturbance should include investigating inherited sensory dysfunction and assessing possible complex genetics or occult-acquired abnormalities. It has been recognised that multiple membrane receptors and channels are involved in responding to pain-provoking stimuli and modulating nociceptive and inflammatory pain, including TRPV1 heat receptor,33 catechol-O-methyltransferase34 and tetrahydrobiopterin.35 Additionally, autoimmune mechanisms for chronic idiopathic pain have been suggested among some patients,36 including those with limited sensory small-fibre neuropathy attributed to IgG autoantibodies binding to voltage-gated potassium complexes.37 Many SCN9A variants can alter the sensitivity to pain, but for a majority of patients with CIP, EM or idiopathic small fibre neuropathy, the pathogenic causes are likely more complex than a single-mutation mechanism.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Mayo Foundation Clinical Research Grant and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant (K08 NS065007-01A1, NS36797).

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design, collecting the data, drafting and revising the manuscript and interpretation of the data: CJK, YW, DHK, PS, MDD, RHG, PAL, PJD. Obtaining the funding, CJK, PJD.

Funding: The authors acknowledge the support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant K08 NS065007 and NS36797.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic.

Disclosures: Christopher J Klein is a coeditor of The Journal of Peripheral Nervous System. Peter J Dyck is a coeditor of Diabetes Care and receives an honorarium.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open Access: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

References

- 1.Davis MD, Weenig RH, Genebriera J, et al. Histopathologic findings in primary erythromelalgia are nonspecific: special studies show a decrease in small nerve fiber density. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:519–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis MD, Sandroni P, Rooke TW, et al. Erythromelalgia: vasculopathy, neuropathy, or both? A prospective study of vascular and neurophysiologic studies in erythromelalgia. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1337–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandroni P, Davis MD, Harper CM, et al. Neurophysiologic and vascular studies in erythromelalgia: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 1999;1:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein CJ. HSAN's clinical features, pathologic classification, and molecular genetics. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK. eds. Peripheral neuropathy . Philadelphia, Saunders, 2005:1809–44 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Mutations in SCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary erythermalgia. J Med Genet 2004;41:171–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox JJ, Reimann F, Nicholas AK, et al. An SCN9A channelopathy causes congenital inability to experience pain. Nature 2006;444:894–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG, International Union of Pharmacology XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev 2005;57:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rush AM, Cummins TR. Painful research: identification of a small-molecule inhibitor that selectively targets Nav1.8 sodium channels. Mol Interv 2007;7:192–5, 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waxman SG. Neuroscience: channelopathies have many faces. Nature 2011;472:173–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fertleman CR, Ferrie CD, Aicardi J, et al. Paroxysmal extreme pain disorder (previously familial rectal pain syndrome). Neurology 2007;69:586–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh NA, Pappas C, Dahle EJ, et al. A role of SCN9A in human epilepsies, as a cause of febrile seizures and as a potential modifier of Dravet syndrome. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han C, Hoeijmakers JG, Ahn HS, et al. Nav1.7-related small fiber neuropathy: impaired slow-inactivation and DRG neuron hyperexcitability. Neurology 2012;78:1635–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faber CG, Hoeijmakers JG, Ahn HS, et al. Gain of function Na(V) 1.7 mutations in idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. Ann Neurol 2012;71:26–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg YP, MacFarlane J, MacDonald ML, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the Nav1.7 gene underlie congenital indifference to pain in multiple human populations. Clin Genet 2007;71:311–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss J, Pyrski M, Jacobi E, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in sodium channel Nav1.7 cause anosmia. Nature 2011;472:186–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Human Genome Mutation Database HGMD SCN9A. 2012. http://www.biobase.com/hgmd [cited (accessed Jun 2012)]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyck PJ, Litchy WJ, Lehman KA, et al. Variables influencing neuropathic endpoints: the rochester diabetic neuropathy study of healthy subjects. Neurology 1995;45:1115–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein CJ, Sinnreich M, Dyck PJ. Indifference rather than insensitivity to pain. Ann Neurol 2003;53:417–18; author reply 8-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyck PJ, O'Brien PC, Johnson DM, et al. Quantitative sensation testing. In: Dyck PJ. ed. Peripheral neuropathy. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005:1063–93 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low PA, Caskey PE, Tuck RR, et al. Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test in normal and neuropathic subjects. Ann Neurol 1983;14:573–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fealey RD, Low PA, Thomas JE. Thermoregulatory sweating abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc 1989;64:617–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyck PJ, Mellinger JF, Reagan TJ, et al. Not ‘indifference to pain’ but varieties of hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy. Brain 1983;106:373–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurban M, Wajid M, Shimomura Y, et al. A nonsense mutation in the SCN9A gene in congenital insensitivity to pain. Dermatology 2010;221:179–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han C, Dib-Hajj SD, Lin Z, et al. Early- and late-onset inherited erythromelalgia: genotype-phenotype correlation. Brain 2009;132(Pt 7):1711–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drenth JP, te Morsche RH, Guillet G, et al. SCN9A mutations define primary erythermalgia as a neuropathic disorder of voltage gated sodium channels. J Invest Dermatol 2005;124:1333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuels ME, te Morsche RH, Lynch ME, et al. Compound heterozygosity in sodium channel Nav1.7 in a family with hereditary erythermalgia. Mol Pain 2008; 4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reimann F, Cox JJ, Belfer I, et al. Pain perception is altered by a nucleotide polymorphism in SCN9A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:5148–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raymond CK, Castle J, Garrett-Engele P, et al. Expression of alternatively spliced sodium channel alpha-subunit genes. Unique splicing patterns are observed in dorsal root ganglia. J Biol Chem 2004;279:46234–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Server EV NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ (accessed 24 May 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vargas-Alarcon G, Alvarez-Leon E, Fragoso JM, et al. A SCN9A gene-encoded dorsal root ganglia sodium channel polymorphism associated with severe fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ames A., 3rd CNS energy metabolism as related to function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev [Review] 2000;34:42–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persson AK, Black JA, Gasser A, et al. Sodium-calcium exchanger and multiple sodium channel isoforms in intra-epidermal nerve terminals. Molecular Pain [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.]. 2010;6:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung MK, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Role of TRP channels in pain sensation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2011;704:615–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science 2003;299:1240–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tegeder I, Costigan M, Griffin RS, et al. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nat Med 2006;12:1269–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paticoff J, Valovska A, Nedeljkovic SS, et al. Defining a treatable cause of erythromelalgia: acute adolescent autoimmune small-fiber axonopathy. Anesth Analg 2007;104:438–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein CJ, Lennon VA, Aston PA, et al. Chronic pain as a manifestation of potassium channel-complex autoimmunity. Neurology 2012;79:1136–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low VA, Sandroni P, Fealey RD, Low PA. Detection of small-fiber neuropathy by sudomotor testing. Muscle Nerve 2006;34:57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]