Abstract

This 3-generation, longitudinal study evaluated a family investment perspective on family socioeconomic status (SES), parental investments in children, and child development. The theoretical framework was tested for first generation parents (G1), their children (G2), and for the children of the second generation (G3). G1 SES was expected to predict clear and responsive parental communication. Parental investments were expected to predict educational attainment and parenting for G2 and vocabulary development for G3. For the 139 families in the study, data were collected when G2 were adolescents and early adults and their oldest biological child (G3) was 3–4 years of age. The results demonstrate the importance of SES and parental investments for the development of children and adolescents across multiple generations.

In contemporary American society, considerable emphasis is placed on individual efforts as means toward achievement. As a result, Americans are more willing to acknowledge the role of internal characteristics in influencing achievement than external factors like socioeconomic status (Lareau, 2003). Despite this emphasis on individual responsibility for achievement, social background still seems to play a role. For example, low socioeconomic status (SES) has been found to limit a) children’s readiness for kindergarten (Ramey & Ramey, 2004), b) access to quality schools and supplies (Lareau, 2003), and c) postsecondary education and career chances (Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998; Sandefur, Meier, & Campbell, 2006).

The influence of SES discrepancies permeates throughout the lifespan, with individuals experiencing effects before kindergarten entry and beyond termination of schooling. SES’s power extends further once individuals reproduce and the next generation experiences continued influence of earlier SES. One way in which parents’ SES may influence the next generation is via early vocabulary development and subsequent educational attainment. That is, parents’ SES has been linked to children’s academic achievement and cognitive and language development (e.g., Roberts, Bornstein, Slater, & Barrett, 1999), but the process by which SES affects these outcomes is not yet understood, especially across multiple generations.

Our goal was to evaluate mechanisms by which two different markers of SES, parent education and family income, influence vocabulary and educational development for children and adolescents. A unique aspect of this study is that SES-related parental investments in children were examined across three familial generations. That is, we consider the relations among first generation (G1) SES and parental investments during the second generation’s (G2’s) adolescence and G2 educational attainment during early adulthood. We then examine the same investment process regarding the children (G3) of these young adults, resulting in an intergenerational examination of the potentially far reaching influence of SES.

Family income and parental education are widely accepted indicators of SES representing different types of capital. Income measures financial capital and education measures human capital (e.g., Conger & Dogan, 2007; Conger & Donellan, 2007; Hoff, Laursen, & Tardif, 2002; Oakes & Rossi, 2003). Theoretically, human capital affects children’s development by shaping parents’ goals for offspring such that their own human capital promotes human capital in the next generation (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). For instance, parents’ education may directly shape expectations for children’s educational attainment as well as investments in children’s learning. More highly educated parents may spend more time communicating with their children and assisting their children with learning efforts (Conger & Dogan, 2007; Guo & Harris, 2000). In contrast to human capital which requires the investment of parents’ time, financial capital provides parents with opportunities to invest in goods, products, and services that enhance learning (Yeung, Linver, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Thus, benefits of parental education and income may have lasting impacts on the development and achievements of children.

These arguments derive from what Conger and colleagues (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Conger & Dogan, 2007) have called the family investment model. This perspective originated in the economics literature (e.g., see Mayer, 1997) and Conger and colleagues as well as others (e.g., Guo & Harris, 2000; Yeung et al., 2000) have extended the model from one solely concerned with income to one encompassing more general aspects of SES (i.e., income and parental education). The model proposes parents with higher income and more educational attainment will make greater interpersonal and material investments in children’s development than lower-SES parents forced to focus on immediate needs (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Schofield, et al., 2011). Such investments likely lead to more positive developmental outcomes.

Some suggest associations among SES, family interaction processes, and child development may vary by gender (see McLoyd, 1998 for a review), but studies addressing such differences often support more similarity than differences in parents’ socialization of boys versus girls (see Lytton & Romney, 1991). Still, since differences have been supported in parents’ teaching with boys versus girls (e.g., Crowley, Callanan, Tenenbaum, & Allen, 2001) and in children’s behaviors toward fathers versus mothers (e.g., Leaper & Gleason, 1996), we examined the predictions in the family investment model separately for males and females when possible.

Evaluating the Family Investment Model across Generations

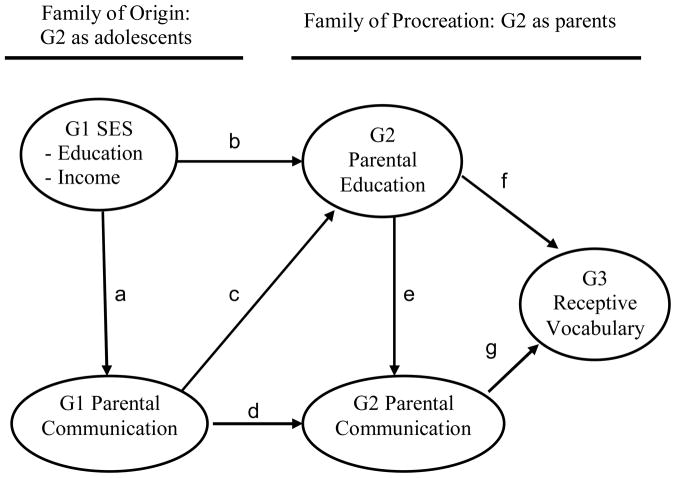

The proposed 3-generation model (Figure 1) guiding this study begins with the direct relation between G1 SES (i.e., income and education) and G2 educational attainment (see Figure 1, Path b). A central proposition is that family SES will lead to greater human capital formation for children as they grow to adulthood (Mayer, 1997). Consistent with this hypothesis, research has shown that children from higher compared to lower income families tend to complete more years of education (e.g., Considine & Zappalà, 2002; Duncan et al., 1998; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Kohen, 2002; Sobolewski & Amato, 2005; Turner & Johnson, 2003) and children with better educated parents experience greater educational success (e.g., Sandefur et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

A 3-Generation Family Investment Model.

The family investment model also proposes that association between parental SES and child development is explained, in part, by both material and interpersonal investments parents make in children. The model in Figure 1 focuses on investments in the form of clear and responsive communication between parent and child. Previous evaluations of the investment model have focused on emotional (e.g., parenting beliefs, parenting behaviors, monitoring, childrearing enjoyment) and material investments (e.g., reading materials, learning materials, neighborhood, health insurance, quality of residence) in the G2 on G3 adaptive outcomes (Schofield et al., 2011), but none have considered intergenerational continuities in parental communication or its impact on learning outcomes during late adolescence (G2) or vocabulary development during early childhood (G3). Admittedly, parental communication probably covaries with other parenting aspects, and is one specific element of investments in children with evident relevance to vocabulary development and educational achievement.

Multiple factors underlie proposed differences in parental communication among higher versus lower SES families. Possibly, having more income reduces stress from financial worries and leaves parents with more time and cognitive resources available for richer, clearer verbal communication. Alternatively, more general lifestyle differences may shape parents’ values and schemas of how to speak with children, meaning higher SES parents spend more time speaking patiently and extensively with children and adolescents out of belief they should do so rather than ability to do so. Indeed, both ideas have been tested, but it appears that SES-related differences in parental communication reflect general differences in verbal communication with all others, not just children (Hoff, 2003a). These overall communication differences include that higher SES mothers tend to generally speak more, speak longer, and use more diverse vocabulary (Hoff, 2003a), thus increasing the likelihood that offspring are exposed to a variety of words used in a rich assortment of ways. When parents deliver this rich verbal communication responsively and flexibly, with expectation and encouragement for reciprocation, they go beyond merely offering word exposure by affording verbal practice opportunities to their offspring.

Consistent with the investment model, we expect G1 SES will influence G2 educational attainment both positively and indirectly via the degree of clear and responsive parental communication during G2’s adolescence (paths a and c). This proposed mediated pathway represents the core explanatory hypothesis of the family investment model, that higher SES parents invest more resources in efforts to promote children’s learning (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Linver et al., 2002; Mayer, 1997). Although previous research demonstrates interpersonal investments enhance cognitive or academic outcomes for children with either income (e.g., Linver et al., 2002) or education used to measure SES (e.g., Hoff, 2003b; see Conger & Donnellan, 2007 for a review), and although recommendations to parents seeking to foster kindergarten readiness have included engaging in rich and responsive communication (Ramey & Ramey, 2004), few studies have considered these dynamics in adolescents’ lives. Consistent with the model, research indicates more parent-adolescent conflict is associated with declines in academic achievement during adolescence (Dotterer, Hoffman, Crouter, & McHale, 2008), while data from our own study has indicated more positive parent communication during adolescence promotes greater academic achievement (e.g., Melby & Conger, 1996).

Noteworthy, however, is that we only predict G2 educational attainment as a marker of later SES because the G2 target participants were assessed relatively early during their adult years, at an average age of about 23 years. Income at this time is not a good indicator of SES inasmuch as many of the participants who will attain the highest SES (i.e., those who eventually will have the highest incomes and years of education) may have relatively low incomes at this age. Indeed, education is considered by many to be the canonical element of SES because of its influence on later income and occupational status (Krieger, Williams, & Moss, 1997). For these reasons, we chose education as the measure of SES for G2 participants.

In a process similar to the dynamic proposed for links between G1 and G2, G2 educational attainment is expected to shape G3’s vocabulary development. Though the reasoning here is the same, more evidence supports this hypothesis during childhood than during adolescence. That is, better educated parents have been found to have young children with more advanced language development (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002; Gest, Freeman, Domitrovich, & Welsh, 2004; Hoff & Tian, 2005; Raviv, Kessenich, & Morrison, 2004; Turner & Johnson, 2003) and higher overall IQ (Linver et al., 2002). Interestingly, more educated mothers seem to expect their children to say first sounds and words and to “think” sooner (Hoff et al., 2002). Expecting more advanced child vocabulary will likely increase parents efforts to encourage younger children’s learning experiences via clear and responsive communication (see also Lareau, 2003).

We selected vocabulary as the G3 outcome because of its critical importance to development across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Schoon, Parsons, Rush, & Law, 2010). Of particular relevance, children’s ability to understand a variety of words is an essential component of kindergarten readiness (Bierman et al., 2008; Doherty, 1997; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). For instance, successful entry into kindergarten requires basic skills, many dependent on vocabulary, including abilities to understand explanations and follow instructions. Children with limited vocabularies should experience more difficulty during classroom activities. Such early academic problems, rather than fading with time, may place students on a persistent trajectory of academic problems (Shonkoff & Philips, 2000), including repeating a grade, requiring special education services, or leaving high school without obtaining a diploma (Brooks-Gunn, Guo, & Furstenberg, 1993; Ramey & Ramey, 2004).

Moreover, young children with more advanced vocabulary do better in school over time and demonstrate greater academic achievement (Jorgenson & Jorgenson, 1996). Consequently, preschool-aged G3 children with larger vocabularies will likely eventually achieve more academically on average and thus have access to more diverse higher educational and career opportunities. Similarly, it is likely that the G2 young adults who achieved the most academically typically had above average vocabulary skills as young children.

Another step involves the direct path (d) from G1 to G2 parental communication. While parental communication style has important implications for children’s vocabulary development, little is known regarding the mechanisms by which parents learn to communicate with children. Possibly, parents learn from interactions with their parents during their own childhood and adolescence (see Conger, Belsky, & Capaldi, 2009: Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005). Indeed, previous research using the same data as the current study demonstrates intergenerational continuity in parenting (e.g., Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scaramella, 2003; Scaramella & Conger, 2003), although none of these previous studies examined continuity in parental communication styles as in the present study. Certainly, evidence suggests continuity over discontinuity in parenting across generations (Belsky et al., 2005; Campbell & Gilmore, 2007; Van IJzendoorn, 1992). Thus, as adolescents transition to adulthood and become parents, they likely adopt communication styles similar to those of their parents. This is an important addition to the basic investment perspective because types of learning promoted by family SES may shape interpersonal processes affecting intergenerational continuities. Consistent with the predictions for G1 and G2, we also propose that G2’s educational attainment will predict responsive communication to their (G3) young children (path e).

The final step in the investment model (Figure 1) involves influence of G2 educational attainment and responsive communication on G3 children’s receptive vocabulary. Receptive vocabulary is defined as the ability to comprehend words through listening or hearing (Dunn & Dunn, 1981). Although nearly all children learn to understand and produce language, the quality and quantity of language acquisition seems dependent on environmental circumstances. During early childhood the diversity and complexity of the words parents utter to children seem to positively influence children’s vocabulary development (Bornstein, Haynes, & Painter, 1998; Hart & Risley, 1995; Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer, & Lyons, 1991). Early vocabulary development may result at least in part from parental investments in communicating with children, as reflected by path g. Previous evidence indicates parents with higher educational attainment use more words and take on a more supportive style of teaching when interacting with children (Duncan & Magnuson, 2003; Richman, Miller, & Levine, 1992). Because we cannot be certain this one form of investment entirely explains the association between G2 young adults’ educational attainment and G3 children’s vocabulary development, we also include a direct path (f) between these two variables.

To summarize, the present study sought to evaluate the hypothesized pathways in the family investment model (Figure 1) with a 3-generation sample. This involves intensive focus on mechanisms of intergenerational continuities in SES and parental communication and the consequences of SES and parental investments on child development than previous studies with this data (e.g., Schofield, et al., 2011). The following analyses addressed four predictions:

G1 parents with more education and income will have children who obtain more education, and this association will be accounted for, in part, because parents with more education and income will demonstrate more clear and responsive communication styles with their children.

G2 adolescents who go on to achieve higher educational attainment will have children with more advanced vocabulary development, partly because they will exhibit clear and responsive communication patterns when interacting with their children.

G1 parents with more income and education will have adolescents who grow up to communicate responsively and clearly with their G3 children, with this parental communication style modeled from a similar style displayed by the G1 parents and partly influenced by greater educational attainment by the G2 adolescents.

G1 parents with greater income and education will have G3 grandchildren who exhibit more advanced vocabulary development, with this intergenerational link being partially shaped by the greater educational attainment of the G2 offspring of G1.

Method

Participants

Participants drew from the Family Transitions Project (FTP), a prospective, longitudinal study of 559 target youth, their families, and selected close relationships. Initial interviews were conducted with G1 and G2 participants between 1989 and 1991, when G2 were either in seventh or ninth grade. In the original sample, 451 adolescents came from two-parent families and 108 came from single-parent, mother-headed families. FTP participants were recruited to examine effects of the economic downturn in agriculture of the 1980s and were recruited from eight rural Iowa counties. Given that there were almost no ethnic minority children living in these counties then (approximately 1% of the population), all participants were White. Most families were characterized as lower-middle- or middle-class based on self-reported incomes.

Data were collected from G1 parents only during G2’s adolescence. Investigators continued to assess G2 participants annually beyond their high school years. To reflect changing focus on family transitions, G3 children of G2 target participants were recruited to participate starting in 1997. Eligible G3 children were the oldest biological child of the G2 target participant, at least 18 months of age, and lived with the G2 target participant at least 2 weekends a month. On average, 90% of the G2 target parents with eligible children agreed to participate in annual assessments with their G3 child. G3 children recruited between 1997 and 2003 were eligible for the present study. Only three-generation families with data available during the adolescent period, the early adult period, and during their child’s preschool years (i.e., 3 or 4 years old) were included in the present analysis. By only including preschool aged children, we were able to measure vocabulary during a developmental period allowing for valid assessments.

Of the 147 families with a 3–4 year old G3 child, 139 had completed the receptive vocabulary assessment and were eligible to be included in the study. Eight vocabulary scores were missing either because of interviewer error or because G3 children were uncooperative during assessments. On average, G3 children were 36.8 months of age during the preschool assessment. Most of the G3 children were boys (55% boys; 45% girls). G2 parents averaged 22.12 years of age at the time of their G3 child’s assessment and included 39.8% men and 60.2% women. Although marital status or cohabitation was not a criterion for participation, 64% of parents were married and 21% were cohabitating with a romantic partner. The remaining 15% of parents were single. Most of the G2 parents (69.8%) were living with the other biological parent of the G3 child. All target G2s were custodial parents.

Procedures: Family of origin assessments of G1 and G2 (1991 – 1994)

Trained interviewers visited all participating families on two occasions during the 9th, 10th and 12th grade assessment periods (i.e., 1991i.e., 1992, and 1994). Each visit lasted about two hours. During the first visit, family members completed a series of questionnaires, some of which included reports of G1 educational attainment and household income. During the second visit, family members participated in four structured videotaped interactions. Family interaction tasks were designed to evoke variations in qualities of family interaction. Only the family discussion task and the problem-solving task involved G1 parents and G2 adolescents and were used in the present report. During the family discussion task parents and adolescents discussed typical daily living issues such as parenting, school performance, and household responsibilities (25 minutes). During the problem-solving task, family members attempted to resolve issues that were presently a source of disagreement within the family (15 minutes).

Trained observers coded the family discussion and problem-solving interactions using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). Behavioral codes examining G1 parents’ communication with G2 participants during adolescence (i.e., 9th, 10th and 12th grade) were included in these analyses.

Procedures: Family of procreation assessments of G2 – G3 (1997 – 2003)

After G2 target participants graduated from high school, they continued to participate annually. Beginning in 1997, G2 participants with an eligible G3 child completed an additional one-hour in home visit with their child. Assessments with G3 children begin when G3 children are between 18 and 27 months of age (2 year old assessment) and continue on an annual schedule until children are 7 years of age. Data for this study were collected when the G3 children were approximately 3 or 4 years of age. These assessments occurred for different families at different points in time, depending on when the G3 child was born. Thus, data used in these analyses involving G3 could have been collected at any time from 1997 to 2003.

During the in home assessments involving G3, children participated in many structured activities, some included in the present report. First, children completed an 8 minute free play activity. For the first three minutes they played alone, and for the next five minutes with the interviewer. This free play was not coded. Next, interviewers administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981) to G3 children. Standard scores from the PPVT-R are used in analyses. G3 children also were videotaped with the G2 parent completing two commonly used structured activities; a puzzle completion task (5 minutes) and a clean-up task (10 minutes). In the puzzle task, G3 children were presented with a puzzle too difficult for them to complete alone. As in other studies using similar tasks for observing parent-child interaction (e.g., Keenan & Wakschlag, 2000, van der Mark, Bakermans-Kranenberg, & van IJzendoorn, 2002), G2 target parents were instructed to let children complete as much of the puzzle on their own as possible, but to offer any assistance they felt was necessary.

The clean-up task occurred at the end of the 60-minute assessment battery. After the G3 child played with various toys for three minutes alone, the interviewer joined the child and played for an additional five minutes. During the joint play, the interviewer dumped out all toys to standardize the amount of toys the G3 children had to clean up. Once free play was over, interviewers retrieved the G2 target parent and instructed the parent that the child needed to clean up all the toys and, while the target parent could offer any assistance necessary, the child was to clean up independently as much as possible. Later, trained observers coded the puzzle and clean-up tasks using the IFIRS (Melby & Conger, 2001). Behavioral codes measuring G2 parents’ communication with their G3 children during both tasks were included in analyses.

Measures for the family of origin: 1991, 1992, and 1994

G1 parent per capita income

During 1991, 1992, and 1994 assessments, G1 provided reports of their current economic circumstances (see Table 1 for data collection timeline summary). First, parents reported on all sources of income including all money from jobs and investments. Second, a household size score was created by summing all family members living in the home. Per capita income was calculated by dividing total income by the number of people in the home. The per capita incomes were averaged across the 3 assessments to create a stable measure of G1 per capita income during G2’s adolescence. To avoid problems with estimation using large numbers, G1 per capita income was divided by 1,000 for final analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of Data Collection: What, When, and From Whom

| Family of Origin: G2s’ adolescence | Family of Procreation: G2’s early adulthood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Construct | 9th grade (1991) | 10th grade (1992) | 12th grade (1994) | G3: 3 – 4 years of age |

| SES | ||||

| 1. Per capita income | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | Not included |

| 2. Parental education | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | G1 mother & father1 self-reports | G2 self-reports |

| Parental communication | Observational ratings: G1 mothers & fathers1 with G2 | Observational ratings: G1 mothers & fathers1 with G2 | Observational ratings: G1 mothers & fathers1 with G2 | Observational ratings: G2 with G3 |

| G3 Receptive vocabulary | Interviewer administered | |||

Most participating families were included the two biological parents of the G2 adolescents, however one-fifth of participating families were from single parent households. The aggregate of mother and father data were used. If fathers were unavailable, only mother data were used.

G1 parent education

During 1991, 1992, and 1994 assessments, G1 mothers and fathers reported highest level of education completed. G1 mother and father education scores thus indicated total number of years of education completed by each parent. Mothers’ and fathers’ highest levels of education also were averaged to create a single G1 parental education score, indicating the average years of formal education completed.

G1 parental communication

The latent construct for parental communication indicated the degree to which parents communicated with adolescents in a clear, positive and cogent manner. This measure also evaluated the degree to which parents listened to and responded to G2, thus promoting the communication and language use skills of G2. Three of 22 dyadic interaction scales in the IFIRS (Melby & Conger, 2001) focus specifically on quality of communication from parent to child. These ratings were generated during the family discussion and problem-solving tasks and were used as three separate indicators for this latent construct. Both the problem solving and family discussion tasks included three to four family members: G1 fathers (when applicable), G1 mothers, G2 target adolescents, and one G2 sibling. Separate scores were originally generated for mothers’ behavior towards target, mothers’ behavior towards sibling, and mothers’ behavior towards father, for instance, and the behavior of other family members was not considered when assigning scores. For the present study, only the ratings based on an individual parent’s behavior directed towards the G2 adolescent were used in analyses. All behaviors were rated on a 9-point continuum ranging from no evidence (1) to highly characteristic (9). The three behavioral rating scales used as indicators of the latent construct were 1) communication, 2) listener responsiveness, and 3) assertiveness.

The communication scale measured the level of G1 parents’ (mothers’ or fathers’) verbal expressive skills as well as content of statements during verbal exchanges with G2. This scale is used to rate the parents’ ability to neutrally or positively express their own point of view, needs, wants, etc., in a clear and reasonable manner, and to demonstrate consideration of the G2 adolescents’ points of view (Melby & Conger, 2001). Behaviors coded within the communication code include use of explanations, clarifications, reasoning, soliciting the views of others that are considerate of the G2 participants’ points of view, encouraging explanations and clarifications, as well as responding reasonably to the ongoing conversation.

The listener responsiveness scale assessed the degree to which G1 parents attend to, show interest in, acknowledge, and validate the verbalizations of the G2 through use of nonverbal backchannels and verbal assents. This scale rated the parents’ nonverbal and verbal responsiveness as a listener to the verbalizations of the G2 through behaviors that validate and indicate attentiveness to the adolescent (Melby & Conger, 2001). Responsive listeners are oriented to the speaker, convey interest in the conversation, and make the speaker feel heard.

Finally, the assertiveness scale measured quality of G1 parents’ verbal presentation by evaluating the degree to which G1 parents express themselves with confidence and forthrightness while expressing points of view clearly. Specifically, this scale evaluated G1 parents’ ability to express themselves through clear, appropriate, neutral or positive avenues using an open, straightforward, nonthreatening, and non-defensive style (Melby & Conger, 2001).

Inter-rater reliability was computed separately for each task by randomly selecting 25% of videotapes to be coded by a second observer (i.e., double-coding). Intraclass correlations are used to asses interobserver agreement, and agreement between single scales like the three used in the current investigation range from .55 to .85 (Kerig & Lindahl, 2001). Twenty-five percent of the interaction tasks were coded by two independent observers and the indicator scores demonstrated substantial inter-rater reliability (average intraclass correlation coefficient = .87).

In addition to its demonstrated reliability, the IFIRS has been validated. First, convergent validity of the scales has been demonstrated when correlated with reports of similar behaviors from self and other family members based on correlational and confirmatory factor analyses (see Conger et al., 2002; Melby, Ge, Conger, & Warner, 1995). In addition, the IFIRS has demonstrated predictive validity with rural Iowa families and minority families from the South and Midwest (Conger et al., 2002). Melby and colleagues report similar findings on the reliability and validity of the IFIRS (Melby, Bryant, & Hoyt, 1998; Melby & Conger, 2001).

Identical coding procedures were used across the adolescent period for all assessments (i.e., 9th, 10th and 12th grades). Data reduction involved averaging scores for each code across the two tasks and three time points separately for each parent. Mothers’ and fathers’ scores were significantly correlated within task. Because some families were recruited when parents had recently experienced a divorce, no father data were available for 22% of G2 adolescents. For initial modeling, G1 mothers’ and fathers’ scores were used separately and we evaluated whether parameter estimates were similar or different by parent gender. When differences were not found between parents, the mean of mother and father scores was used as a composite variable in the final analyses. If data from fathers was not available, then only mother scores were used.

Family of procreation measures: 1997 – 2003

G2 target parent education

When G3 children were 3 or 4 years old, G2 participants reported their highest level of education to date. The G2 parental education score reflects total number of years of formal education completed by the G2 target.

G2 target parental communication

Analyses included G2 target parents’ (either mother or father) communication measured when G3 were 3 or 4 years of age. Observational tasks such as the clean-up and puzzle tasks have been used previously to assess parents’ communication with preschool-aged children (e.g., Landry, Miller-Loncar, Smith, & Swank, 2002; van der Mark et al., 2002). The same communication, listener responsiveness, and assertiveness codes used to measure G1 communication were used as the three indicators for G2 target parents’ latent communication construct. No modifications were made to definitions for behavioral ratings and separate teams of coders rated G1 and G2 parents’ communication. That is, while parents’ behaviors and word choices may differ when addressing a young child as compared to an adolescent, qualitative aspects of communication style remained consistent with the manual.

Observers rated G2 target parents’ communication, listener responsiveness, and assertiveness during interactions with G3 children during the puzzle and clean-up tasks. As with other studies using these observational tasks, only one parent (the G2 target, either a father or a mother) was present with the G3 child. All codes were rated on the same as for G1, ranging from no evidence of the behavior (1) to highly characteristic (9). The three global behavioral ratings were averaged across the two tasks to create three indicators of G2 target parents’ communication, listener responsiveness, and assertiveness with G3 children. Two independent observers also coded 25% of the tasks to measure inter-rater reliability (average intra-class correlation coefficient = .83). Different coders rated G1 and G2 communication.

G3 child receptive vocabulary

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981) was used to measure G3 children’s receptive vocabulary. The PPVT-R consists of a series of words for which respondents are required to select a picture best representing the word from a set of four drawings. Children must achieve a basal, or minimum, score demonstrating they understand how to complete the test and are able to meet basic test criteria. Children continue to identify words until they get eight or more incorrect in a single 12-item block. One advantage of the PPVT-R is that norms have been created based on age. The average score for each age is set at 100 with a standard deviation of 15.

Results

Prior to hypothesis testing, the current sample of 139 G2s and their families was compared to the original sample of 559 G2s on G1 SES and communication. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) procedures were used to evaluate the extent to which these characteristics varied across participants from the current sample versus non-participating members of the original sample. The only statistically significant difference that emerged involved G1 education; G2 targets in the current study had G1 parents completing significantly fewer years of education than non-participating G2 targets (F = 6.84; p < .01; mean of non-participating G1 = 13.72 years). This difference likely reflects that adolescents and young adults with parents with a lower than average level of education tend to have children earlier (Scaramella, Neppl, Ontai, & Conger, 2008). The intergenerational subsample in the present analyses demonstrated no differences in terms of family income or interpersonal investments (i.e., G1 communication).

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations among Study Constructs

Table 2 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and correlations for study constructs. Combined scores for G1 mothers and fathers were used. As expected, all correlations were positive and most were statistically significant. For example, G2 education was positively correlated with G1 income (r = .17) and G1 education (r = .31). G2 targets completed slightly more education (M = 13.57 years; SD = 1.73) than G1 parents (M = 12.92 years; SD =1.46). Consistent with the theoretical model (Figure 1), G1 education and income were positively correlated with G1 communication. Also consistent with the model, G1 communication was significantly correlated with G2 education, G2 communication, and G3 receptive vocabulary. G2 education also was significantly associated with G2 communication and G3 receptive vocabulary. Given this preliminary support for several of the hypothesized pathways in the theoretical model, the next step was to evaluate the full theoretical model depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Summary of the Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Final Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G1 Education | - | 12.92 | 1.46 | |||||

| 2. G1 Income | .41** | - | 6.59 | 4.67 | ||||

| 3. G1 Communication | .27** | .24** | - | 4.60 | 0.94 | |||

| 4. G2 Education | .31** | .17** | .21** | - | 13.57 | 1.73 | ||

| 5. G2 Communication | .23** | .13 | .35** | .48** | - | 5.33 | 1.11 | |

| 6. G3 Vocabulary | .18** | .09 | .16* | .28** | .48** | - | 93.84 | 15.51 |

p < .05 (two-tailed test);

p < .05 (one-tailed test)

Evaluation of the Structural Equation Model (SEM)

Structural equation models were estimated using Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) and full information maximum likelihood. The latter provides more consistent, less biased estimates than ad hoc procedures for dealing with missing data (Arbuckle, 1996; Schafer, 1997). We first evaluated a model which treated G1 mothers’ and fathers’ education and communication as separate constructs. Because each parent contributed to varying degrees to household income, income was not estimated separately by parent sex.

To determine whether mother and father effects were significantly different, we estimated a model with corresponding paths constrained to equality and another with these paths freely estimated. Chi-square values for competing nested models were compared, and a nonsignificant difference in χ2 values indicated constrained parameters were not significantly different. Each pair of paths was tested separately and four of the five pairs of paths were not significantly different. That is, mother and father effects did not differ significantly for these four effects. A significant difference was found for the fifth pair in that income positively and significantly affected mother’s communication, but not father’s. However, testing all five sets of paths simultaneously did not result in a significant deterioration of model fit, indicating that overall, mother and father effects are not significantly different. Given this and the limited utility of separating these effects, we present the results for the more parsimonious model with G1 mother and father measures combined into G1 parent measures as described earlier.

We conducted multiple group analysis to test for G3 child gender differences in the paths directly linked to G3 vocabulary, as well as to test for G2 gender differences in all paths directly linked to G2 constructs. Our results indicated no significant G3 gender differences; however, there were significant differences between G2 males and females. Thus, models were estimated allowing separate estimates on parameters that differed significantly by G2 gender. When no significant gender differences were found, a parameter was constrained to equality across groups. Particularly noteworthy, even when a path coefficient is constrained to be equal across groups, the standardized estimates may differ for females and males because of differences in variances.

Figure 2 presents the results of SEM evaluating the family investment model. Fit indices affirm that the model demonstrated adequate fit with the data: The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is less than .05 and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is greater than .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All factor loadings were significant, in the expected direction and of relatively large magnitude (see Table 3).

Figure 2.

Results of the structural equation model evaluating the family investment model. Standardized estimates for G2 males are left of the slash and to the right for G2 females (male/female). Coefficient in bold indicates significant differences between G2 males and females; χ2=89.852, df=78, comparative fit index=0.982, root mean square error of approximation=0.047; ** p < .05 (two-tailed test); * p < .05 (one-tailed test).

Table 3.

Standardized Factor Loadings for the Full Structural Model

| Construct | Indicator | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|

| G1 Communication | Communication | .97 |

| Listener Responsiveness | .75 | |

| Assertiveness | .92 | |

| G2 Communication | Communication | .87 |

| Listener Responsiveness | .80 | |

| Assertiveness | .84 |

Hypothesis 1: G1 parents with more education and income will have children who obtain more education, and this association will be accounted for, in part, because parents with more education and income will demonstrate more clear and responsive communication styles with their children

The results presented in Figure 2 indicate, consistent with predictions, G1 tended to use a more responsive and clear communication style with adolescents when parents had more education (β = .17; p < .05) or income (β = .17; p < .05). G2 adolescents whose parents used a responsive communication style tended to be more responsive in communicating with their G3 children, both as mothers (β = .24; p < .05) and as fathers (β = .23; p < .05). Similarly, male adolescents whose parents had exhibited more clear and responsive communication attained more years of education (β = .37; p < .05). This pattern was not supported, however, for G2 female adolescents. Also consistent with the model, adolescents of both sexes whose parents had more education attained more education themselves (β = .27; p < .05). However, G1 income was not significantly associated with G2 educational attainment. Although simple correlational analysis indicated G2 adolescents whose parents had higher educational attainment exhibited more clear and responsive communication with their children once they became parents, the findings of the SEM analysis suggest this link is accounted for by the relation between G1 parental communication and G2 adolescents’ eventual educational attainment. This notion was further supported by tests using the delta method to calculate the standard errors of indirect effects (β = .12; p <.05, two-tailed tests; Sobel, 1982).

Hypothesis 2: G2 adolescents who go on to achieve higher educational attainment will have children with more advanced vocabulary development, partly because they will exhibit clear and responsive communication patterns when interacting with their children

G2 educational attainment did predict their level of responsive communication which, in turn, was significantly associated with their children’s vocabulary (see Figure 2). Especially important, the previously significant correlation between G2 parents’ educational attainment and G3 vocabulary (r=.28, Table 2) became non-significant when controlling for degree of responsive communication. Furthermore, the test of the indirect effect of G2 educational attainment on G3 vocabulary via their level of clear and responsive communication was significant (G2 males, β = .18; G2 females, β = .21). Taken together, these results indicate G2 parents’ communication style with their children mediated the positive link between their level of education and G3 vocabulary development, consistent with the investment hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: G1 parents with more income and education will have adolescents who grow up to communicate responsively and clearly with their G3 children, with this parental communication style modeled from a similar style displayed by the G1 parents and partly influenced by greater educational attainment by the G2 adolescents

Support for this hypothesis was mixed. The results depicted in Figure 2 indeed indicate G1 parents who demonstrated clear and responsive communication patterns during G2’s adolescence had offspring who, as parents, tended to use similar communication patterns with their G3 children. G1 educational attainment, on the other hand, seemed to predict G2 parental communication style primarily through G2 educational attainment. Such a pattern indicates socioeconomic factors in G1 predict the degree to which parents present a responsive parental communication style which will likely be emulated by the G2 offspring once they have children.

Hypothesis 4: G1 parents with greater income and education will have G3 grandchildren who exhibit more advanced vocabulary development, with this intergenerational link being partially shaped by the greater educational attainment of the G2 offspring of G1

The findings support this hypothesis. G1 parents with higher income and educational attainment had grandchildren exhibiting more advanced vocabulary development, with this relation explained by G2’s greater educational attainment and more clear and responsive parental communication (G2 males, β = .05; G2 females, β = .06). Furthermore, G1 parents exhibiting a more responsive parental communication style also had G3 grandchildren with significantly higher vocabulary by way of G2 responsive parental communication (G2 males, β = .09; G2 females, β = .11). A similar pattern was supported regarding this indirect path from G1 responsive communication style and G3’s more advanced vocabulary development through G2’s greater educational attainment, but it was only significant for G2 males (β = .07).

Evaluation of alternative models

Finally, a series of alternative models was considered. We re-estimated the model in a number of ways. First, we evaluated the impact of G3 children’s own communication style on their parents’ communication style. Then, since G2 targets had children at different ages and G3 children’s age varied slightly within the sample, we re-estimated the model controlling for age of both G2 and G3 participants. The following section summarizes these findings.

First, we re-estimated the model depicted in Figure 1 considering influence of G3 children’s own communication patterns directed towards parents on parental communication patterns. Importantly, children’s communication was measured using the same indicators of communication, listener responsiveness, and assertiveness as with their parents. To test children’s role in shaping parents’ communication patterns, we added a latent G3 children’s communication construct and added an additional path from children’s communication to G2 parental communication. While results supported a statistically significant relation between communication patterns of G2 and G3 (β = .42, p < .01), inclusion of this path reduced the overall model fit, as indicated by a statistically significant chi-square (χ2 [56] = 104.50; p < .01), a CFI of .94 and a RMSEA of .08. Importantly, including the additional path did not alter the pattern of significant findings or direction of relations reported in Figure 2. Thus, children’s communication to parents does not account for or change the results reported in Figure 2.

Next, we considered the influence of G2 and G3 age on the overall results. Not surprisingly, G2 age emerged as a significant predictor of both educational attainment and communication patterns with G3 children. Again, controlling for G2 target parent age diminished model fit but did not alter the pattern of relations among any constructs. Similarly, when G3 children’s age was added as a control variable, no statistically significant paths resulted. Thus, neither G2 nor G3 participant age altered the set of findings reported in Figure 2.

Discussion

The present study examined continuities in SES and its consequences across three generations. The family investment model guided the analysis (e.g., Conger & Donnellan, 2007) and results present a complex picture of intergenerational relations between SES and adolescent and child development. In particular, structural equation analyses revealed positive associations between G1 parents’ SES and interpersonal investments in their children. Both parental income and education predicted responsive communication to G2 during adolescence which, in turn, predicted educational attainment, but only for G2 sons. In addition, G1 educational attainment was significantly associated with educational attainment of G2 sons and daughters.

Moreover, as expected G2 educational attainment was associated with their communication style with their G3 children which, in turn, predicted more advanced G3 vocabulary development. In contrast to expectations, parental educational attainment was not directly associated with children’s vocabulary and results indicated that G2 target parents’ degree of clear and responsive communication with their children mediated the association between their education level and their children’s vocabulary. This finding is consistent with the most conservative prediction from the family investment model hypothesizing parental investments will completely account for expected association between parent SES and child development. The following sections will first discuss the results related to the family investment model and then describe the limitations, strengths, and the implications of these results for future research.

An Intergenerational Evaluation of the Family Investment Model

The family investment model proposes higher compared to lower SES parents have children exhibting more academic success at school (e.g., Considine & Zappalà, 2002; Linver et al., 2002) and more likely to pursue postsecondary education (e.g., Duncan et al., 1998; Sandefur et al., 2006). Theoretically, benefits accrue because higher SES parents have time for more interpersonal investments and the financial means for more material investments. In this investigation, parents’ use of clear and responsive communication with their children was hypothesized to be an important parental investment through which SES would shape development across generations. Use of a 3-generational design allowed for a direct evaluation of the family investment model as well as a within family replication of the investment process.

Interesting findings emerged regarding parent-adolescent relations between G1 and G2 which may establish the foundation for later parent-child relations between G2 and G3. First, we anticipated G1 SES would predict G2 human capital formation both in terms of educational attainment and eventual parenting skills. Both G1 income and education predicted G1 responsive communication which, in turn, predicted communication quality of G2 offspring. These results add a new marker of human capital (i.e., responsive communication) to outcomes previously considered in tests of the family investment model (e.g., Schofield, et al., 2011).

With regard to prediction of G2 educational attainment, results are more complex. G1 educational attainment predicted G2 educational attainment while their income did not. This is particularly relevant for professionals seeking to bolster educational opportunities for low-income children and adolescents. With the financial aspect of SES less predictive than parental education, we have further evidence that poverty need not be destiny. Low income presents an obvious practical obstacle to educational attainment, but financial limitations may be overcome when parents value academic accomplishment and encourage offspring to pursue postsecondary education. Our findings support G1 parents’ education, then, as the key element of SES molding later generations’ academic readiness and achievement. Parental education appears more relevant to later generations’ success when considering its relation to parental communication.

G1 parents’ personal investments, in the form of clear and responsive communication, were significantly associated with G2 educational attainment at the bivariate level, with this association only reaching significance for G2 sons in SEM analyses. Future research explicitly testing potential sex differences in the relation between parental communication and educational attainment is clearly warranted. Some research indicates family and parenting factors are associated with adolescent educational achievement and attainment differently for boys than for girls (Deslandes, Bouchard, & St-Amant, 1998; Hindin, 2005). Girls possibly profit most from examples parents provide via their own educational attainment. Boys, though, may be affected both by parents as models and by interpersonal investments received from higher SES parents.

In contrast, G2 clear and responsive communication fully mediated the association between their educational attainment and their G3 children’s vocabulary in all estimated models, suggesting such an interaction style may play a critical role in maintaining intergenerational continuities in academic readiness and success. This result provided stronger than expected support for the investment hypothesis inasmuch as there are many material and interpersonal investments that higher SES parents may make to encourage the competent development of their children. For instance, parental education is frequently proposed to have a powerful relation with children’s cognitive ability even during the toddler years (e.g., Roberts et al., 1999). Similarly, an accumulation of social risk has been found to indirectly undermine language development during infancy by affecting parents’ ability to establish an environment supportive of learning and language growth (Burchinal, Vernon-Feagans, Cox & Key Family Life Project Investigators, 2008). Given the difference in developmental stages between G3 children and G2 young adults, finding the relation between G2 education and G3 vocabulary is mediated by G2 communication patterns makes sense. That is, vocabulary development has been found to predict later educational attainment, but actual educational achievement is far off for G3. Nonetheless, the path to ultimate educational attainment begins with transition to kindergarten or first grade. A more successful transition is enhanced with more advanced vocabulary skills and a positive example set by parents. The combination of advanced vocabulary skills and parents’ use of responsive communication may place children on a trajectory of increasing academic competence, thereby affecting their future educational attainment.

Importantly, parents are not the only adults who communicate with preschool-aged children. Young children also may engage in verbal interchanges with other family members, neighbors, and child care providers. Frequency and quality of these verbal exchanges may influence children’s vocabulary development. In fact, quality of out-of-home child care predicts early cognitive and language development even when controlling for family characteristics (Burchinal et al., 2000; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). Interestingly, more affluent parents are more likely to secure high quality child care and may be better able to invest in out-of-home experiences enhancing children’s vocabulary and academic competencies.

In the present study, parents’ clear and responsive communication emerged as a mediator of the intergenerational transmission of educational attainment and vocabulary development. These results are consistent with previous work linking responsive parental communication with more enriched vocabularies during early childhood (e.g. Hart & Risley, 1995; Huttenlocher et al., 1991; Weizman & Snow, 2001). However, our parental communication measure was based on global ratings of parents’ communication during videotaped structured parent-child interactions rather than typical measurement of communication patterns involving counting the variety of words parents use (e.g., Bornstein et al., 1998) or the quantity of verbalizations (e.g., Hart & Risley, 1995; Huttenlocher et al., 1991). In other words, coders rated qualitative aspects parental dialogue. Higher communication scores reflected clearer and more assertive speech that builds upon and responds to the statements and interests of the child. Such a pattern may be effective in teaching adolescents how to communicate clearly and effectively in academic and career settings and may have the added benefit of promoting vocabulary growth in the next generation.

Especially noteworthy, however, is that the current findings at least suggest a similar family investment process across two different generations in the same families. The G2 to G3 findings indicate higher SES in the form of parental education promotes parental investments in children’s learning process. Importantly, these investments appear to explain the link between parental education and aspects of cognitive and language development. Consistent with the family investment model predictions, G1 parental investments may have initiated developmental trajectories influencing G2 educational attainment. That is, the relation between G1 SES and G2 educational attainment likely began with similar parental investments when G2 were young children, not just through patterns of G1 communication during adolescence. Nevertheless, these findings demonstrate parental investments mediate the impact of SES on academic or cognitive outcomes for adolescents in a process similar to that for younger children. In that sense, these results provide a unique contribution to our understanding of SES and family investment process.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations are noteworthy. First, the sample is unique. Intergenerational studies are expensive and require ongoing participation. Indeed the present sample has participated for nearly 20 years. Moreover, only G2 participants with a child 18 months or older and who were willing to complete an additional interview were included. Consequently, the youngest parents in our sample are disproportionately represented. Given that this study is ongoing, we expect to replicate these findings as the number of participating G2 parents increases. Second, the observational tasks used to measure communication were of short duration in specific contexts. Although G1 communication was based on three 35 minute interactions over a 4 year period, the G2–G3 interactions lasted a total of 15 minutes. Replication is clearly needed. Possibly, some of the findings reported here involve genetic mediation, although a recent study found no evidence for genetic influence on sensitive parenting (Fearon, et al., 2006) and McGuire (2010) recently reported observational measures of parenting of the type used in the present study demonstrate little if any evidence of heritability. Nonetheless, genetically-informed research designs will need to be pursued in the future to address possible genetic influences on these processes.

Third, the sample consisted primarily of White families in rural areas, potentially limiting the generalizability of results. Replications with minority and rural families will increase confidence in these results. Fourth, the investigation only assessed one aspect of language competence, receptive vocabulary. While strongly related to measures of expressive language and full scale IQ (Kutsick, Vance, Schwarting, & West, 1988), the PPVT-R only measures the number of words children recognize. Additional research relating parental SES and communication to other measures clearly is warranted. Furthermore, we only considered one type of parental investments, namely quality of parental communication. Previous research using data from the same sample has indicated that emotional and material investments also impact G3 children’s adjustment (e.g., Schofield, et al., 2001). Other factors, such as overall involvement, sensitivity, responsiveness not limited to communication, and breadth of vocabulary also may account for observed associations and likely covary with our communication measure.

Finally, as with other developmental research, our findings may be culture-specific. For example, contemporary American culture places value on education for both males and females. It is likely that results would differ with families living within a culture prohibiting or limiting educational opportunities for females. The fact that our study participants exhibited highly similar levels of educational attainment for males and females is probably a reflection of Western cultural standards and opportunities afforded to females.

Despite limitations, results of the present study indicate benefits of parental investments in the form of clear and responsive parental communication extend beyond family of origin to influence features of parental behavior and vocabulary development within the next generation. More generally, SES in one generation was not only associated with cognitive development and educational achievement in the next generation, SES also appears to promote patterns of communicating that foster outcomes that are adaptive in modern Western academic settings.

Future research also would benefit from studying vocabulary and other language aspects once children enter kindergarten. For example, experiences within formal academic settings may compensate for situations in which parents do not make sufficient interpersonal investments in vocabulary development. In some cases children who lag behind peers in vocabulary development because they are exposed to less verbal communication at home or because parents have language barriers interfering with ability to help children may catch up once they interact with others at school (see Connor, Morrison, & Underwood, 2007). Possibly, parents with more education also are more familiar with the educational system and engage in communication patterns that valued in a school setting. Less well educated parents may communicate with children in ways consistent with behaviors valued within their communities, but these styles may be less compatible with a school setting. Alternatively, such children may enter school at a disadvantage and continue to struggle and fall behind over time (see Lloyd & Hertzman, 2009). Following children longitudinally from the preschool period through early school years would clarify how quality of early parent-child communication influences children’s academic adjustment and would aid intervention efforts to maximize children’s academic success.

Future studies considering measures of other types of human investments also are needed. Although we considered qualitative aspects of parents’ communication with children, quantity of time spent with children and number of learning resources available to children also may influence children’s vocabulary growth and school readiness more broadly. Additionally, children’s exposure to educational media, like television and video games, may augment parents’ efforts to enrich verbal communication. Importantly, these results indicate qualitative features of parents’ communication patterns may have both within and across generational influences.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (HD064687, HD051746, MH051361, and HD047573). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Contributor Information

Sara L. Sohr-Preston, Department of Psychology, Southeastern Louisiana University

Laura V. Scaramella, Department of Psychology, University of New Orleans

Monica J. Martin, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis

Tricia K. Neppl, Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University

Lenna Ontai, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis.

Rand Conger, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of California, Davis.

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee SR, Sligo J, Woodward L, Silva PA. Intergenerational transmission of warm-sensitive-stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3-year-olds. Child Development. 2005;76:384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich RL, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Nelson KE, Gill S. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI Program. Child Development. 2008;79:1802–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes MO, Painter KM. Sources of child vocabulary competence: A multivariate model. Journal of Child Language. 1998;25:367–393. doi: 10.1017/S0305000998003456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Guo G, Furstenberg FF. Who drops out of and who continues beyond high school? A 20-year follow-up of black urban youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1993;3:271–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0303_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Pianta R, Howes C. Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:415–436. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(02)00107-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Riggins R, Zeisel SA, Neebe E, Bryant D. Relating quality of center-based child care to early cognitive and language development longitudinally. Child Development. 2000;71:339–357. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Vernon-Feagans L, Cox M Key Family Life Project Investigators . Cumulative social risk, parenting, and infant development in rural low-income communities. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2008;8:41–69. doi: 10.1080/15295190701830672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Gilmore L. Intergenerational continuities and discontinuities in parenting styles. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2007;59:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Belsky J, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: Closing comments for the special section. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1276–1283. doi: 10.1037/a0016911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Dogan SJ. Social class and socialization in families. In: Grusec J, Hastings P, editors. Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ebert-Wallace L, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the Family Stress Model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella LV. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CM, Morrison FJ, Underwood PS. A second chance in second grade: the independent and cumulative impact of first- and second-grade reading instruction and students’ letter-word reading skill growth. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2007;11:199–233. [Google Scholar]

- Considine G, Zappalà G. The influence of social and economic disadvantage in the academic performance of school students in Australia. Journal of Sociology. 2002;38:129–148. doi: 10.1177/144078302128756543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley K, Callanan MA, Tenenbaum HR, Allen E. Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science. 2001;12:258–261. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes R, Bouchard P, St-Amant JC. Family variables as predictors of school achievement: sex differences in Quebec adolescents. Canadian Journal of Education. 1998;23:390–404. doi: 10.2307/1585754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dotterer AM, Hoffman L, Crouter AC, McHale SM. A longitudinal examination of the bidirectional links between academic achievement and parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:762–779. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07309454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson KA. Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. doi: 10.2307/2657556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RMP, Van IJzendoorn MH, Fonagy P, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Schuengel C, Bokhorst CL. In search of shared and nonshared environmental factors in security of attachment: A behavior-genetic study of the association between sensitivity and attachment security. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gest SD, Freeman NR, Domitrovich CE, Welsh JA. Shared book reading and children’s language comprehension skills: The moderating role of parental discipline practices. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:319–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Harris KM. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development. Demography. 2000;37:431–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hindin MJ. Family dynamics, gender differences and educational attainment in Filipino adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:299–316. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. Causes and consequences of SES-related differences in parent-to-child speech. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003a. pp. 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development. 2003b;74:1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Laursen B, Tardif T. Socioeconomic status and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 2: Biology and ecology of parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Tian C. Socioecomonic status and cultural influences on language. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2005;38:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Haight W, Bryk A, Seltzer M, Lyons T. Early vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:236–248. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson CB, Jorgenson DE. Concurrent and predictive validity of an early childhood screening test. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;84:97–102. doi: 10.3109/00207459608987254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Wakschlag LS. More than the terrible twos: The nature and severity of behavior problems in clinic-referred preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:33–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1005118000977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systematic research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:341–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsick K, Vance B, Schwarting FG, West R. A comparison of three different measures of intelligence with preschool children identified at-risk. Psychology in the School. 1988;25:270–275. doi: 10.1002/1520-6807(198807)25:3<270::AID-PITS2310250308>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Miller-Loncar CL, Smith KE, Swank PR. The role of early parenting in children’s development of executive processes. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2002;21:15–41. doi: 10.1207/S15326942DN2101_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Berkely, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leaper C, Gleason JB. The relationship of play activity and gender to parent and child sex-typed communication. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:689–703. doi: 10.1080/016502596385523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J, Kohen DE. Family processes as pathways from income to young children’s development. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:719–734. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JEV, Hertzman C. From kindergarten readiness to fourth-grade assessment: Longitudinal analysis with linked population data. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, Romney DM. Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:267–296. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SE. What Money Can’t Buy: Family Income and Children’s Life Chances. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S. The heritability of parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2010;3:73–94. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0301_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Bryant CM, Hoyt WT. Effects of observers’ ethnicity and training on ratings of African American and Caucasian parent-youth dyads. In: Cauce AM Chair, editor. Issues in multi-cultural/multi-ethnic observational research; Symposium conducted at the seventh biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Diego. 1998. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. Parental behaviors and adolescent academic performance: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Ge X, Conger RD, Warner TD. The importance of task in evaluating positive marital interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:981–994. doi: 10.2307/353417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and child development: Results from the NICHD study of early child care and youth development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. The relation of child care to cognitive and language development; pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Rossi PH. The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:769–784. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Early learning and school readiness: Can early intervention make a difference? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:471–491. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2004.0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv T, Kessenich M, Morrison FJ. A meditational model of the association between socioeconomic status and three-year-old language abilities: The role of parenting factors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:528–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richman AL, Miller PM, LeVine RA. Cultural and educational variations in maternal responsiveness. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:614–621. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.4.614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E, Bornstein MH, Slater AM, Barrett J. Early cognitive development and parental education. Infant and Child Development. 1999;8:49–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-7219(199903)8:1<49::AID-ICD188>3.0.CO;2-. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur GD, Meier AM, Campbell ME. Family resources, social capital, and college attendance. Social Science Research. 2006;35:525–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children’s negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]