Abstract

The current research examined co-rumination (extensively discussing, rehashing, and speculating about problems) with mothers and friends. Of interest was exploring whether adolescents who co-ruminate with mothers were especially likely to co-ruminate with friends as well as the interplay among co-rumination with mothers, co-rumination with friends, and anxious/depressed symptoms. Early- to mid-adolescents (N = 393) reported on co-rumination and normative self-disclosure with mothers and friends and on their internalizing symptoms in this cross-sectional study. Co-rumination with mothers (but not normative self-disclosure) was concurrently associated with adolescents' co-rumination with friends. In addition, the relation between co-rumination with mothers and adolescents' anxious/depressed symptoms reported previously (Waller & Rose, 2010) became non-significant when co-rumination with friends was statistically controlled. This suggests that the relation between friendship co-rumination and anxious/depressed symptoms may help explain the relation between mother-child co-rumination and anxious/depressed symptoms. Potential implications for promoting adolescents' well-being are discussed.

Co-rumination, or excessively discussing, rehashing, and speculating about problems, and dwelling on negative feelings (Rose, 2002), may carry both risks and benefits. To date, co-rumination primarily has been studied in the friendships of children and adolescents and young adults. In friendships, co-rumination is linked with positive relationship quality (Calmes & Roberts, 2008; Rose, 2002; Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007) but also internalizing symptoms (Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010; Rose et al., 2007; Starr & Davila, 2009; Stone, Uhrlass, and Gibb, 2010).

Given the links between friendship co-rumination and adjustment, considering potential predictors of friendship co-rumination is a critical next step. The current study is motivated by the idea that mothers’ co-rumination with their children may predict the development of the children’s co-rumination with friends. The current study examines the concurrent relation between mother-child co-rumination and adolescents’ co-rumination with friends. Establishing the concurrent association would lay the groundwork for future prospective studies to consider mother-child co-rumination as a factor that may contribute to the development of youths’ co-rumination with friends.

Two published studies have examined parent-child co-rumination. One did not include information about youths’ co-rumination with friends (Waller & Rose, 2010). The other study did find a concurrent relation between undergraduates’ co-rumination with parents and their co-rumination with friends (Calmes & Roberts, 2008). The current study considers this association among adolescents. In adolescence, the relation could be stronger (e.g., because adolescents have more interaction with parents) or weaker (e.g., if adolescents avoid behaving like parents to exercise autonomy).

The current study also extends past research by considering interrelations among mother-child co-rumination, friendship co-rumination, and internalizing symptoms. Co-rumination with mothers (Calmes & Roberts, 2008; Waller & Rose, 2010) and co-rumination with friends (Calmes & Roberts, 2008; Hankin et al., 2010; Rose, 2002, Rose et al., 2007; Starr & Davilla, 2009; Stone et al., 2010) are each associated with internalizing symptoms. However, the relation is weaker for mother-child co-rumination. One possibility is that mother-child co-rumination is not directly related to internalizing symptoms. That is, mothers’ co-rumination with their children may influence the development of their children’s co-rumination with friends, which may be the actual predictor of internalizing symptoms. Because the current data are cross-sectional, the temporal ordering of these relations cannot be tested. However, if the current data indicate that the concurrent association between mother-child co-rumination and internalizing symptoms is at least partially accounted for by co-rumination with friends, this could stimulate future longitudinal work that considers friendship co-rumination as an explanatory factor in regards to the impact of mother-child co-rumination on the development of internalizing symptoms.

Finally, normative self-disclosure is taken into account. The possible relationship between normative self-disclosure with mothers and friendship co-rumination is tested. Also, prior studies indicate that the positive relation between co-rumination and internalizing symptoms becomes stronger when normative self-disclosure is controlled (Rose, 2002; Waller & Rose, 2010). This pattern is expected in the current study too and suggests that aspects of co-rumination that are not shared with normative self-disclosure (e.g., rehashing, dwelling on negative affect) are most strongly related to internalizing symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 393; 86.5% European American) were fifth graders (63 girls; 51 boys), eighth graders (83 girls; 57 boys), and eleventh graders (74 girls; 65 boys).

Measures

Friendship Nominations

Adolescents responded to co-rumination and self-disclosure measures about a specific friend. A friendship nomination measure (Parker & Asher, 1993) was used to select this friend. On student rosters, adolescents circled their three best friends and starred the one of the three who was their “very best friend.” To be included in this sample, participants had to have at least one reciprocal friend (they circled a friend who circled them). Participants reported on their highest-priority reciprocal friendship chosen with this hierarchy (Rose, 2002; Rose & Asher, 1999, 2004): (a) adolescent and friend star each other, (b) adolescent stars friend; friend circles adolescent, (c) adolescent circles friend; friend stars adolescent, and (d) adolescent and friend circle each other.

Co-Rumination

Items on Waller and Rose’s (2010) revision of Rose’s (2002) Co-Rumination Questionnaire were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores were means for: (a) co-rumination with mother about adolescent’s problems (8 items, α = .91), (b) co-rumination with mother about mother’s problems (8 items, α = .94), (c) co-rumination with friend about adolescent’s problems (8 items, α = .95), (d) co-rumination with friend about friend’s problems (8 items, α = .96). An example is “When my Mom and I talk about a problem that she has, we try to figure out everything about the problem, even if there are parts that we may never understand.” The correlation between co-rumination with mothers about mothers’ problems and about adolescents’ problems was .68. The correlation between co-rumination with friends about friends’ problems and about adolescents’ own problems was almost perfect (r = .95). Therefore, a single friendship co-rumination score was computed (16 items, α = .98).

Self-Disclosure

Items on the revised Self-Disclosure Questionnaire (Rose, 2002; adapted from Parker & Asher, 1993) were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores were means for: (a) disclosure with mother about adolescent’s problems (5 items, α = .92), (b) disclosure with mother about mother’s problems (5 items, α = .92), (c) disclosure with friend about adolescent’s problems (5 items, α = .95), and (d) disclosure with friend about friend’s problems (5 items, α = .95). An example is “My Mom tells me about her problems.” The correlation between disclosure with mothers about mothers’ problems and adolescents’ problems was .61. Because the correlation between disclosure with friends about friends’ problems and adolescents’ own problems was .93, a single friendship disclosure score was computed (10 items, α = .97).

Anxious/Depressed Symptoms

The anxious/depressed subscale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used. Items were rated on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “Not true” to 2 “Very true or often true.” An item assessing suicidal ideation was dropped. Scores were the mean rating of the remaining 12 anxious/depressed items (α = .81).

Results

Analyses were conducted with the full sample because preliminary analyses indicated that there were not important gender/grade differences in the associations. Analyses first examined whether mother-child co-rumination and self-disclosure were related to friendship co-rumination. Co-rumination with mothers about the mothers’ problems, co-rumination with mothers about the adolescents’ problems, self-disclosure with mothers about the mothers’ problems, and self-disclosure with mothers about the adolescents’ problems were each positively correlated with friendship co-rumination (Table 1). A hierarchical regression analysis tested the unique associations of these mother-child variables with friendship co-rumination (Table 2). Gender and grade were entered on the first step as controls. The mother-child variables were entered on the second step, which was significant. Mother-child co-rumination (about mothers’ problems and about adolescents’ problems) was associated with greater friendship co-rumination. The self-disclosure variables were not associated with greater friendship co-rumination (in fact, with co-rumination controlled, mother-child disclosure about adolescents’ problems was related to lower friendship co-rumination).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | ||||||||

| 2. Grade | .02 | |||||||

| 3. Co-Rumination with Mothers (Child Problems) | −.23**** | −.08 | ||||||

| 4. Co-Rumination with Mothers (Mother Problems) | −.18*** | .03 | .68**** | |||||

| 5. Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Child Problems) | −.35**** | −.17*** | .70**** | .53**** | ||||

| 6. Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Mother Problems) | −.18*** | .32**** | .55**** | .71**** | .61**** | |||

| 7. Friendship Co-Rumination | −.47**** | .11* | .47**** | .52**** | .33**** | .40**** | ||

| 8. Friendship Self-Disclosure | −.49**** | .21**** | .36**** | .34**** | .34**** | .40**** | .76**** | |

| 9. Youth Anxious/Depressed Symptoms | −.22**** | −.14** | .02 | .08 | .01 | −.02 | .18*** | .10* |

Notes.

p ≤ .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Correlations with gender are point-biserial correlations. Girls were coded as 0 and boys as 1.

Table 2.

Summary of Regression Analyses Examining (a) Effects of Self-Disclosure and Co-Rumination with Mothers on Friendship Co-Rumination, (b) Effects of Self-Disclosure and Co-Rumination with Mothers on Adolescents’ Anxious/Depressed Symptoms, and (c) Effects of Friendship Self-Disclosure and Co-Rumination on Adolescents’ Anxious/Depressed Symptoms

| β | t value | R2 | R2 change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = Friendship Co-Rumination | ||||

| Step 1: | .26**** | |||

| Gender | −.47 | 10.86**** | ||

| Grade | .20 | 4.67**** | ||

| Step 2: | .48**** | .22**** | ||

| Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Youths’ Problems) | −.15 | 2.50* | ||

| Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Mothers’ Problems) | .03 | .46 | ||

| Co-Rumination with Mothers (Youths’ Problems) | .26 | 4.32**** | ||

| Co-Rumination with Mothers (Mothers’ Problems) | .33 | 5.42**** | ||

| DV = Anxious/Depressed Symptoms | ||||

| Step 1: | .07**** | |||

| Gender | −.22 | 4.46**** | ||

| Grade | −.14 | 2.81** | ||

| Step 2: | .09**** | .02* | ||

| Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Youths’ Problems) | −.12 | 1.55 | ||

| Self-Disclosure with Mothers (Mothers’ Problems) | −.09 | 1.16 | ||

| Co-Rumination with Mothers (Youths’ Problems) | −.05 | .64 | ||

| Co-Rumination with Mothers (Mothers’ Problems) | .21 | 2.58* | ||

| DV = Anxious/Depressed Symptoms | ||||

| Step 1: | .07**** | |||

| Gender | −.22 | 4.46**** | ||

| Grade | −.14 | 2.81** | ||

| Step 2: | .09**** | .02** | ||

| Friendship Self-Disclosure | −.13 | 1.66 | ||

| Friendship Co-Rumination | .23 | 3.05** | ||

Notes.

p ≤ .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

Girls were coded as 0 and boys as 1.

Next, relations between mother-child co-rumination and self-disclosure with adolescents’ anxious/depressed symptoms were considered. None of the mother-child co-rumination or self-disclosure variables were correlated with anxious/depressed symptoms (Table 1). A regression analysis tested the simultaneous associations of mother-child co-rumination and self-disclosure with adolescents’ anxious/depressed symptoms (Table 2). Gender and grade were entered on the first step. The second step, which included the mother-child variables, was significant. The self-disclosure variables were not associated with anxious/depressed symptoms. Co-rumination about adolescents’ problems also was not associated with anxious/depressed symptoms. However, co-rumination about mothers’ problems was associated with greater anxious/depressed symptoms.

Regarding friendships, both co-rumination and self-disclosure with friends were correlated with anxious/depressed symptoms (Table 1). A regression tested the associations of friendship co-rumination and disclosure simultaneously (Table 2). Gender and grade were entered on the first step. Co-rumination and self-disclosure with friends were entered on the second step, which was significant. Only co-rumination with friends was associated with anxious/depressed symptoms.

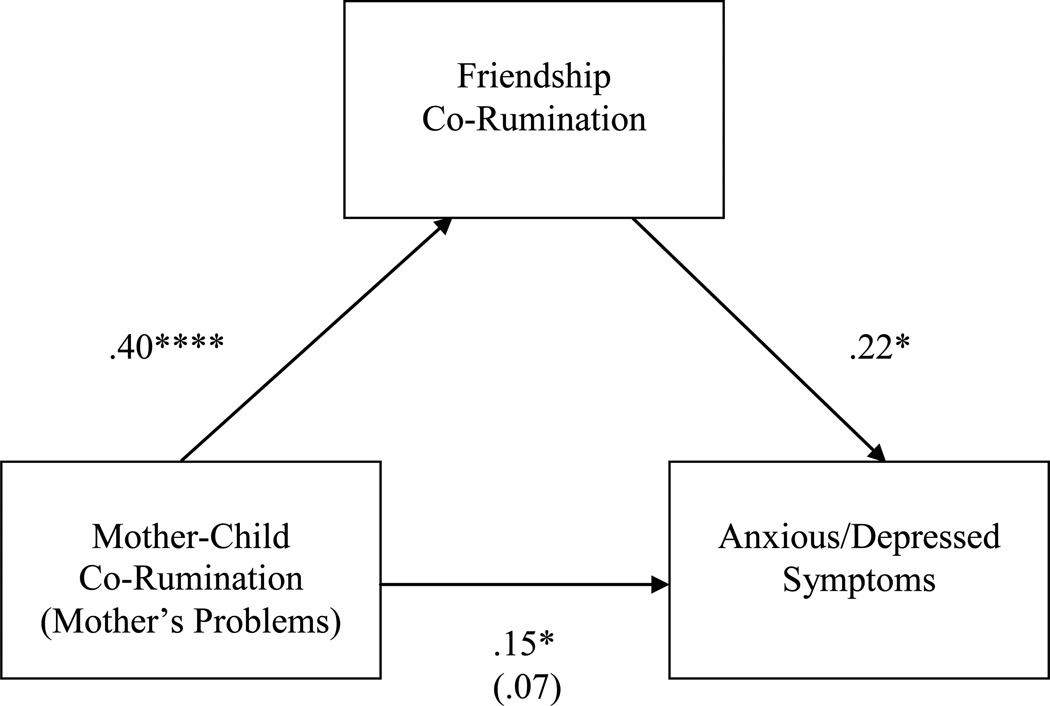

Meditational analyses (Baron & Kenny, 1986) tested whether friendship co-rumination statistically mediated the association of mother-child co-rumination about mothers’ problems with adolescents’ anxious/depressed symptoms (Figure 1). Gender and grade and the motherchild and friendship self-disclosure variables were controlled in all analyses. The first regression indicated that co-rumination with mothers about mothers’ problems was related to anxious/depressed symptoms (β = .15, t = 2.22, p < .05). The second regression indicated that co-rumination with mothers was related to friendship co-rumination (β = .40, t = 9.61, p < .0001). The third regression indicated that friendship co-rumination was related to anxious/depressed symptoms, while controlling for co-rumination with mothers in addition to the covariates (β = .22, t = 2.58, p < .05). In the fourth regression, anxious/depressed symptoms again were predicted from mother-child co-rumination, but this time friendship co-rumination was controlled. Mediation was significant (Sobel’s test, z = 2.49, p < .05), and co-rumination with mothers was no longer significantly associated with anxious/depressed symptoms (β = .07, t = .88).

Figure.

Friendship co-rumination as a statistical mediator of the effect of mother-child co-rumination about mother’s problems on anxious/depressed symptoms. Gender, grade, and self-disclosure variables with mothers and with friends were controlled in analyses. Numbers in this figure represent standardized β coefficients in regression analyses. *p ≤ .05. ****p < .0001.

Discussion

The current study contributes to our growing understanding of the complex construct of co-rumination by providing new information about adolescents’ co-rumination with mothers. Mother-child co-rumination was significantly related to adolescents’ co-rumination with friends. Longitudinal data are now needed to test whether mother-child co-rumination predicts increases in adolescents’ co-rumination with friends over time and to examine the processes through which this may happen (e.g., modeling, reinforcement). This research will be important as third-variable explanations also are possible. For example, there may be heritable aspects of interpersonal styles that mothers’ and their children’s share that contribute to both mothers’ and their children’s co-ruminative styles with each other and with friends. In addition, future research should explore additional nuances of mother-child co-rumination, such as the topics that mothers co-ruminate about with their children.

The results also highlight the importance of simultaneously considering co-rumination and normative self-disclosure. Co-rumination and self-disclosure with mothers both were correlated with friendship co-rumination. However, when co-rumination and self-disclosure were simultaneous predictors, only co-rumination with mothers was associated with greater friendship co-rumination. This suggests that the extreme aspects of co-rumination that are not shared with normative self-disclosure (e.g., rehashing, dwelling on negative affect) are associated with friendship co-rumination.

Results further indicated that the relation between mother-child co-rumination about mothers’ problems and adolescents’ internalizing symptoms became non-significant when co-rumination with friends was controlled. This suggests that co-ruminating with friends may be riskier emotionally than co-ruminating with mothers. However, our ability to draw conclusions is limited by the cross-sectional design. Future longitudinal research is needed to test the proposed temporal ordering of the relations, namely, that mother-child co-rumination predicts friendship co-rumination, which predicts internalizing symptoms. In addition, the possibility of reciprocal relationships should be addressed. For example, bi-directional relations may be present such that co-ruminating contributes to elevated depressive symptoms, which in turn leads to greater co-rumination with mothers and friends (see Rose et al., 2007).

If future research supports the proposed temporal ordering of relations, then there would be notable applied implications. That is, mothers who co-ruminate with their adolescent children should be aware that they may be modeling a communication style that, if replicated with friends, could have negative emotional consequences. Instead, adolescents should be encouraged to develop open communication styles that stop short of co-rumination.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmes CA, Roberts JE. Rumination in interpersonal relationships: Does co-rumination explain gender differences in emotional distress and relationship satisfaction among college students? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Stone L, Wright PA. Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:217–235. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73:1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children's goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:69–79. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Development. 2004;75:749–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM. Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Davila J. Clarifying co-rumination: Associations with internalizing symptoms and romantic involvement among adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LB, Uhrlass DJ, Gibb BE. Co-rumination and lifetime history of depressive disorders in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:597–602. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller EM, Rose AJ. Adjustment trade-offs of co-rumination in mother–adolescent relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]