Abstract

Studies suggest obesity is paradoxically associated with better outcomes for patients with pneumonia. Therefore, we examined the impact of obesity on short-term mortality in patients hospitalized with pneumonia. For 2 years clinical and radiographic data were prospectively collected on all consecutive adults admitted with pneumonia to six hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. We identified 907 patients who also had body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) collected and categorized them as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal (18.5 to <25), overweight (25 to <30) and obese (>30). Overall, 65% were >65 years, 52% were female, and 15% reported recent weight loss. Eighty-four (9%) were underweight, 358 (39%) normal, 228 (25%) overweight, and 237 (26%) obese. Two-thirds had severe pneumonia (63% PSI Class IV/V) and 79 (9%) patients died. In-hospital mortality was greatest among those that were underweight (12 [14%]) compared with normal (36 [10%]), overweight (21 [9%]) or obese (10 [4%], p <0.001 for trend). Compared with those of normal weight, obese patients had significantly lower rates of in-hospital mortality in multivariable logistic regression analyses: adjusted odds ratio (OR), 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22–0.97; p 0.04. However, compared with patients with normal weight, neither underweight (adjusted OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.54–2.4; p 0.7) nor overweight (adjusted OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.52–1.69; p 0.8) were associated with in-hospital mortality. In conclusion, in patients hospitalized with pneumonia, obesity was independently associated with lower short-term mortality, while neither being underweight nor overweight were. This suggests a protective influence of BMIs > 30 kg/m2 that requires better mechanistic understanding.

Keywords: Body mass index, community-acquired pneumonia, mortality, obesity, outcomes

Introduction

Obesity is associated with increased co-morbidity (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnoea) and higher mortality directly proportional to increases in body mass index (BMI) [1–3]. Obesity is also independently associated with an increased risk of acquiring infections such as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [4,5]. Furthermore, obesity could lead to worse outcomes in those who develop infections, perhaps as a result of dysregulation of the inflammatory cascade involving increased levels of cytokines, adiponectin and leptin and exaggerated macrovascular and microvascular responses [4,6]. Obesity also leads to impairments in lung function that include adverse changes in mechanics and airway resistance and impaired gas exchange [7,8]. Last, the accumulation of obesity-related co-morbidities might lead to increased pneumonia-related mortality [8].

Conversely, low weight, especially if associated with malnutrition, may also be a risk factor for acquiring infections such as pneumonia and having poorer infection-related outcomes [8–13]. Unlike the case for obesity, the underlying aetiology of the weight loss (e.g. malignancy, substance use, cardiopulmonary cachexia) is often thought to be the mechanism underlying increased mortality and poorer pneumonia-related outcomes [1,8].

Given that obesity is associated with both an increased risk of developing pneumonia and an increased risk of total mortality, it could be assumed that obese individuals would have worse pneumonia-related outcomes. However, a few studies indicate that obesity may have a protective effect against pneumonia-related mortality [12,14,15]. This so-called ‘obesity paradox’ is poorly understood for acute infections, and therefore we examined the relationship between increased BMI and pneumonia-related mortality. We hypothesized that compared with normal weight, obesity would be associated with decreased in-hospital mortality.

Methods

Setting and Subjects

From 2000–2002, data were collected on a prospective cohort of 3415 people (>17 years) with community-acquired pneumonia who were admitted to six hospitals in Edmonton (population ~ 1 million), Alberta, Canada, and managed according to a clinical pathway. Detailed descriptions of the cohort and data collection methods have been previously published [16,17]. To enter the cohort, subjects had to have signs and symptoms of pneumonia (defined as ≥2 of the following: cough, pleurisy, shortness of breath, temperature >38°C, crackles, or bronchial breathing on auscultation) and a chest radiograph interpreted by the treating physicians as consistent with pneumonia. All patients were cared for according to a validated clinical pathway that had triage and site-of-care suggestions based on the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and recommendations for investigations and antibiotic treatments. Patients with tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, immuno-compromised status (e.g. chronic prednisone or other immunosuppressing agents) or frank aspiration, those who were pregnant or breast-feeding and those who required a direct admission to intensive care unit (ICU) were excluded. The study was exempted from the informed consent requirement and approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada).

Measurements

Data collected included patient sociodemographics (age, sex, residence), clinical characteristics (vital signs, co-morbidities, laboratory values), functional status, prescription drug use, vaccination history, and the official chest radiograph report as interpreted by a board-certified radiologist (vs. the interpretation of pneumonia made by the treating physicians). We categorized patients according to Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria [18] and stress hyperglycaemia at admission (plasma glucose >6.1 mM (>110 mg/dL)) [19]. Functional status in the 2 weeks before admission was determined by patient or proxy interview and classified as completely independent ambulation or impaired. The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), a validated tool for predicting short-term mortality in patients with pneumonia, was used to assess disease severity [16,20].

Independent variable of interest

The study cohort included all individuals with pneumonia who had a BMI measured at the time of admission to hospital. Unlike the data prospectively collected for the study described earlier (e.g. the PSI, chest radiographs), height and weight were not mandated items. Thus, BMI was only captured if available in the patients’ medical chart as part of routine hospital care and was recorded in about one-third of cases (see Results and Appendices 1–3). Patients were categorized according to the conventional World Health Organization (WHO) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) BMI classification: <18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 (normal), 25 to 30 kg/m2 (overweight), >30 kg/m2 (obese) [21]. Related to BMI, we also collected information with respect to weight loss, defined as a self- or proxy-reported loss of weight of ≥ 5% over the preceding 1 year.

Appendix 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of patients with available vs. missing body mass index data.

| Characteristic | Available data N = 907 | Missing data N = 2508 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 68 ± 17 | 69 ± 18 | 0.37 |

| Female, n (%) | 476 (52) | 1327 (53) | 0.82 |

| Non-smoker, n (%) | 652 (72) | 1914 (76) | 0.008 |

| Impaired function, n (%) | 101 (11) | 262 (10) | 0.56 |

| Advanced directive, n (%) | 89 (10) | 296 (12) | 0.11 |

| Nursing home, n (%) | 150 (17) | 487 (19) | 0.06 |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular | 456 (50) | 1204 (48) | 0.24 |

| COPD | 299 (33) | 758 (30) | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (6) | 139 (6) | 0.93 |

| Known cancer | 117 (13) | 382 (15) | 0.09 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 134 (15) | 356 (14) | 0.67 |

| >5 medications, n (%) | 155 (17) | 395 (16) | 0.35 |

| Statins, n (%) | 91 (10) | 234 (9) | 0.54 |

| Pneumovax, n (%) | 287 (32) | 775 (31) | 0.68 |

| Flu vaccine, n (%) | 242 (27) | 663 (26) | 0.89 |

| SIRS >2, n (%) | 716 (79) | 2028 (81) | 0.21 |

| Hyperglycaemia >6.1, n (%) | 580 (64) | 1496 (60) | 0.02 |

| Respiratory rate >30, n (%) | 206 (24) | 584 (24) | 0.85 |

| Pneumonia severity index, n (%) | |||

| Class I/II/III | 332 (37) | 955 (38) | 0.43 |

| Class IV/V | 575 (63) | 1553 (62) | |

| Abnormal chest radiograph, n (%) | 680 (75) | 1767 (70) | 0.01 |

Appendix 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of the 30-day rates of readmission to hospital after surviving pneumonia and being discharged to the community.

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted * odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI group | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.53 (0.69–3.41) | 0.29 | 1.48 (0.66–3.33) | 0.34 |

| 18.5–25 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| 25–30 | 0.96 (0.51–1.84) | 0.91 | 0.98 (0.51–1.87) | 0.95 |

| > = 30 | 0.80 (0.41–1.57) | 0.52 | 0.81 (0.41–1.61) | 0.55 |

| Age > 65 years | 1.23 (0.71–2.13) | 0.45 | 1.20 (0.65–2.22) | 0.56 |

| Pneumonia Severity Index Class IV/V | 0.92 (0.55–1.54) | 0.75 | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.36 |

| Impaired function | 1.92 (0.99–3.72) | 0.06 | 1.86 (0.94–3.66) | 0.07 |

| Pneumovax | 1.38 (0.82–2.33) | 0.54 | 1.34 (0.78–2.32) | 0.27 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 0.86 (0.49–1.52) | 0.61 | 0.84 (0.47–1.49) | 0.54 |

c-statistic = 0.68, p <0.001; Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, p 0.68.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included the need for transfer to the ICU and 30-day all-cause readmission to hospital. For endpoints that took place after hospital discharge, we linked our cohort to routinely updated and previously validated administrative healthcare databases using unique but anonymized identifiers [16].

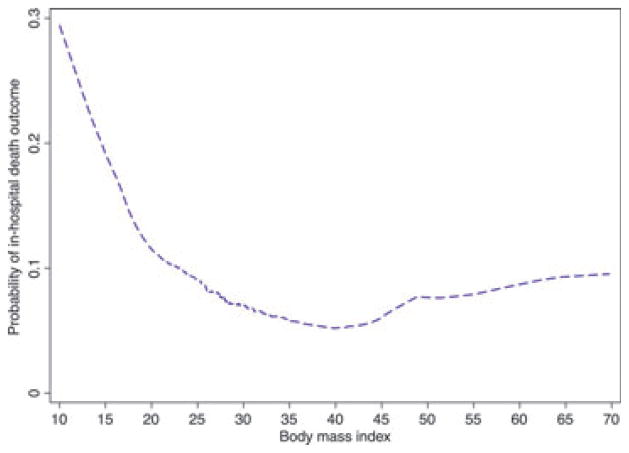

Analysis

We first plotted BMI against mortality using lowess plots. Using multivariable logistical regression, we evaluated the independent association between admission BMI and in-hospital mortality. Individuals with a normal BMI of 18.5–25 kg/m2 served as the reference group. We did not attempt to impute missing values for BMI [22]. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. We only forced pneumonia severity according to PSI class and BMI as an ordinal variable into each model. We then considered variables for inclusion in models if univariate associations with in-hospital mortality were p <0.1 or if the variable was maldistributed across BMI categories or the variable confounded (>10% change in beta coefficient) the association between BMI and mortality. The final multivariable model included age, functional status, prior pneumococcal vaccination, chest radiograph confirmation, PSI and BMI. Hereafter, we refer to this as our fully adjusted model. We used the c-statistic (area under the curve) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test to evaluate our final models.

We then replicated the analysis for in-hospital mortality after excluding those patients with clinically diagnosed pneumonia who eventually had an admission chest radiograph reported as normal. Although chest radiograph abnormalities are conventionally used to confirm the diagnosis of pneumonia, patients presenting with serious lower respiratory tract symptoms and signs are often ‘clinically’ diagnosed with pneumonia, admitted, and treated as such [23].

Finally, we carried out several sensitivity analyses. First, we examined the impact of self-reported weight loss on the outcome of in-hospital mortality. Second, we redid the analyses of in-hospital mortality after excluding patients from nursing homes, as the current definition of ‘community-acquired’ does not include nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Last, we repeated our analytical approach for two non-fatal endpoints: transfer to intensive care unit (ICU) and 30-day hospital readmission rates among those discharged home. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

General characteristics

Of 3415 patients admitted to hospital with pneumonia, 907 (27%) had a BMI measured at admission. There were few clinically important or statistically significant differences between those who had BMI measured and those where it was missing (Appendix 1). The mean age was 68 years (SD = 17), 48% were female and 17% were from nursing homes. Nearly two-thirds of patients (63%) presented with severe pneumonia (Pneumonia Severity Index class IVor V); 79% had two or more SIRS criteria and 64% had stress hyperglycaemia at admission.

BMI and weight

The mean weight for the entire cohort was 73 kg (SD = 23) and the mean BMI was 27 (SD = 8). There were 84 (9%), 358 (39%), 228 (25%) and 237 (26%) individuals in the underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese categories, respectively. (As an aside, in the Edmonton health region, it has been estimated that 34% of adults are overweight and 18% obese [24].) Of note, fully 15% of patients reported recent weight loss. Characteristics of patients stratified by BMI category are presented in Table 1. Compared with normal weight patients (reference group), the underweight patients were more likely to be older, female and nursing home residents, more likely to report recent weight loss, and had more severe pneumonia. Conversely, when compared with normal weight patients, the obese patients were more likely to have diabetes and more likely to present with shortness of breath and tachycardia, but otherwise they had less severe pneumonia (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 907 patients admitted to hospital with pneumonia

| Characteristics | BMI categories

|

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 18.5–25 | 25–30 | >30 | ||

| N (%) | 84 (9) | 358 (39) | 228 (25) | 237 (26) | |

| Weight, kg ± SD | 43 ± 7 | 61 ± 10 | 76 ± 9 | 99 ± 24 | <0.001 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 73 ± 16 | 69 ± 19 | 69 ± 16 | 65 ± 16 | 0.007 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 58 (69) | 161 (45) | 91 (40) | 121 (51) | <0.001 |

| Non-smoker, n (%) | 56 (67) | 261 (73) | 168 (74) | 167 (70) | 0.6 |

| Impaired function, n (%) | 19 (23) | 41 (11) | 23 (10) | 18 (8) | 0.002 |

| Advanced directive, n (%) | 17 (20) | 45 (13) | 14 (6) | 13 (6) | <0.001 |

| Nursing home, n (%) | 23 (27) | 64 (18) | 35 (15) | 28 (12) | 0.009 |

| >5% weight loss, n (%) | 41 (49) | 62 (17) | 16 (7) | 17 (7) | <0.001 |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Cardiovascular | 41 (49) | 171 (48) | 119 (52) | 125(53) | 0.6 |

| COPD | 37 (44) | 117 (33) | 66 (29) | 79 (33) | 0.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (2) | 13 (4) | 12 (5) | 24 (10) | 0.004 |

| Known cancer | 14 (17) | 50 (14) | 32 (14) | 21 (9) | 0.2 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (11) | 55 (15) | 40 (18) | 30 (13) | 0.3 |

| >5 medications, n (%) | 9 (11) | 49 (14) | 44 (19) | 53 (22) | 0.01 |

| Statins, n (%) | 1 (1) | 30 (8) | 29 (13) | 31 (13) | 0.006 |

| Pneumovax, n (%) | 24 (29) | 124 (35) | 69 (30) | 70 (30) | 0.5 |

| Flu vaccine, n (%) | 19 (23) | 109 (30) | 61 (27) | 53 (22) | 0.1 |

| Pneumonia symptoms, n (%) | |||||

| Fever | 30 (36) | 144 (40) | 95 (42) | 95 (40) | 0.8 |

| Cough | 60 (71) | 235 (66) | 160 (70) | 169 (71) | 0.4 |

| Sputum production | 35 (42) | 153 (43) | 116 (51) | 115 (49) | 0.2 |

| Shortness of breath | 57 (68) | 230 (64) | 159 (70) | 180 (76) | 0.03 |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 5 (6) | 34 (10) | 38 (12) | 26 (11) | 0.4 |

| Altered mental status | 20 (24) | 61 (17) | 30 (13) | 26 (11) | 0.02 |

| Pneumonia signs, n (%) | |||||

| Respirations >30 bpm | 23 (28) | 75 (22) | 48 (22) | 60 (27) | 0.4 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 43 (51) | 166 (46) | 91 (40) | 124 (52) | 0.05 |

| Systolic pressure <90 mmHg | 4 (5) | 14 (4) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 0.6 |

| Crackles on auscultation | 30 (36) | 137 (38) | 90 (39) | 88 (37) | 0.9 |

| SIRS ≥2 criteria | 70 (83) | 271 (76) | 176 (77) | 199 (84) | 0.06 |

| Hyperglycaemia >6.1 mM | 51 (61) | 199 (56) | 162 (71) | 168 (71) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 70 (83) | 280 (78) | 169 (74) | 161 (68) | 0.009 |

| Pneumonia severity index, n (%) | |||||

| Class I | 2 (2) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (3) | 0.004 |

| Class II | 5 (6) | 49 (14) | 36 (16) | 57 (24) | |

| Class III | 16 (19) | 64 (18) | 47 (21) | 42 (18) | |

| Class IV | 32 (38) | 158 (44) | 92 (40) | 88 (37) | |

| Class V | 29 (35) | 82 (23) | 51 (22) | 43 (18) | |

| PSI score, mean ± SD | 112 ± 34 | 106 ± 35 | 104 ± 34 | 97 ± 35 | <0.001 |

In-hospital mortality in the overall cohort

Overall, 79 (9%) patients died in hospital. A curvilinear trend with higher rates of unadjusted mortality in the underweight group and much lower unadjusted mortality rates in the obese group was observed (Fig. 1). Specifically, there were 12 (14%) deaths in the underweight, 36 (10%) in the normal weight, 21 (9%) in the overweight and 10 (4%) in the obese category. Table 2 displays those variables significantly associated with in-hospital mortality in univariable analyses. In unadjusted analysis, obesity was associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality compared with the normal weight category (4% vs. 10% mortality for normal weight; unadjusted OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.19–0.81; p 0.01; Table 3). In fully adjusted models, obesity was still independently associated with a significantly lower rate of in-hospital mortality compared with normal weight (adjusted OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22–0.97; p 0.04). However, mortality rates in the underweight (adjusted OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.54–2.4; p 0.7) and overweight groups (adjusted OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.52–1.69; p 0.8) were not significantly different compared with normal BMI (Table 3). The adjusted model for in-hospital mortality performed well according to the c-statistic (0.78, p <0.001) and goodness-of-fit tests (p 0.92).

FIG. 1.

Rates of in-hospital pneumonia-related mortality according to body mass index.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients with pneumonia significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (univariable analysis)

| Characteristics | Alive | In-hospital death | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 828 (91) | 79 (9) | |

| Body mass index categories, n (%) | |||

| <18.5 | 72 (9) | 12 (15) | 0.02 |

| 18.5–25 | 322 (39) | 36 (46) | |

| 25–30 | 207 (25) | 21 (27) | |

| > = 30 | 227 (27) | 10 (13) | |

| Weight, kg ± SD | 74 ± 23 | 68 ± 23 | 0.02 |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 67 ± 17 | 77 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| Non-smoker, n (%) | 585 (71) | 67 (85) | 0.008 |

| Impaired function, n (%) | 80 (10) | 21 (27) | <0.001 |

| Advanced directive, n (%) | 753 (91) | 65 (82) | 0.01 |

| Nursing home, n (%) | 131 (16) | 19 (24) | 0.06 |

| >5% weight loss, n (%) | 117 (14) | 19 (24) | 0.02 |

| Co-morbidities n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular | 401 (48) | 55 (70) | <0.001 |

| Known cancer | 101 (12) | 16 (20) | 0.04 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 117 (14) | 17 (22) | 0.08 |

| Pneumovax, n (%) | 270 (33) | 17 (22) | 0.04 |

| Pneumonia symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Fever | 344 (42) | 20 (25) | 0.005 |

| Cough | 577 (70) | 47 (59) | 0.06 |

| Sputum production | 394 (48) | 25 (32) | 0.007 |

| Pneumonia signs, n (%) | |||

| Respirations >30 bpm | 180 (23) | 26 (35) | 0.02 |

| Systolic pressure <90 mmHg | 24 (3) | 6 (8) | 0.03 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 613 (74) | 67 (85) | 0.03 |

| Pneumonia severity index, n (%) | |||

| Class I | 16 (2) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Class II | 146 (18) | 1 (1) | |

| Class III | 165 (20) | 4 (5) | |

| Class IV | 336 (41) | 34 (43) | |

| Class V | 165 (20) | 40 (51) | |

| PSI score, mean ± SD | 101 ± 34 | 131 ± 30 | <0.001 |

TABLE 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis for in-hospital mortality of 907 patients with pneumonia

| Unadjusted odds ratios | p-value | Adjusted* odds ratios | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index categories | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.49 (0.74–3.00) | 0.3 | 1.13 (0.54–2.39) | 0.7 |

| 18.5–25 (reference) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 25–30 | 0.91 (0.52–1.60) | 0.7 | 0.94 (0.52–1.69) | 0.8 |

| > = 30 | 0.39 (0.19–0.81) | 0.01 | 0.46 (0.22–0.97) | 0.04 |

| Age > 65 years | 3.27 (1.74–6.14) | <0.001 | 2.33 (1.18–4.60) | 0.02 |

| Impaired function | 3.39 (1.95–5.87) | <0.001 | 2.95 (1.64–5.30) | <0.001 |

| Pneumovax | 0.57 (0.33–0.99) | 0.05 | 0.39 (0.22–0.70) | 0.002 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 1.96 (1.04–3.69) | 0.04 | 1.84 (0.95–3.55) | 0.07 |

| Pneumonia Severity Index Class IV/V | 9.66 (3.86–24.2) | <0.001 | 7.11 (2.75–18.38) | <0.001 |

c-statistic for model = 0.78, p <0.001; Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, p 0.92.

In-hospital mortality in those with abnormal chest radio-graphs

When analyses were restricted to the 680 patients with chest-radiograph confirmed pneumonia, the findings were even more striking: there were 12 (17%) in-hospital deaths in the underweight, 30 (11%) in the normal weight, 19 (11%) in the overweight and 6 (4%) in the obese category. Even though the sample size was reduced by 227 patients, the independent association between obesity and in-hospital mortality became larger and more significant: adjusted OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12–0.78; p 0.01 (Table 4). The adjusted model for in-hospital mortality in this subgroup analysis performed well according to the c-statistic (0.79, p <0.001) and goodness-of-fit tests (p 0.87).

TABLE 4.

Fatal and non-fatal endpoints in 907 patients hospitalized with pneumonia, according to categories of body mass index

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | Death, n (%) | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p-value | Transfer to ICU, n (%) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | p-value | 30-day readmission, n (%) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 12 (14) | 1.13 (0.54–2.39) | 0.7 | 13 (15) | 0.55 (0.28–1.09) | 0.1 | 9 (11) | 1.48 (0.66–3.33) | 0.3 |

| 18.5–25 | 36 (10) | 1.00 | REF | 79 (22) | 1.00 | REF | 26 (7) | 1.00 | REF |

| 25.1–30 | 21 (9) | 0.94 (0.52–1.69) | 0.8 | 45 (20) | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 0.6 | 16 (7) | 0.98 (0.51–1.87) | 0.9 |

| >30 | 10 (4) | 0.46 (0.22–0.97) | 0.04 | 42 (18) | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | 0.3 | 14 (6) | 0.81 (0.41–1.61) | 0.6 |

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; REF, reference.

Models adjusted for age, functional status, prior pneumococcal vaccination, chest radiograph confirmation and Pneumonia Severity Index.

Sensitivity analyses

First, inclusion of self-reported weight loss into the multivariable models did not alter the relationship observed between obesity and in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.22–0.99; p 0.05); in addition, the interaction term between weight loss and BMI was not significant (p 0.17).

Second, after excluding 150 nursing home patients from analyses, the association between obesity and in-hospital mortality became even stronger and remained statistically significant (adjusted OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.10–0.63; p 0.004).

Third, there were 179 (20%) ICU transfers and 65 (7%) re-hospitalizations within 30 days. Compared with normal weight, there was no independent association between obesity and ICU transfer (adjusted OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.50–1.21; p 0.3) or 30-day readmission rates (adjusted OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.41–1.61; p 0.6 and Table 4). The same pattern held true when non-fatal endpoints were examined in analyses restricted to patients with abnormal chest radiographs (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Fatal and non-fatal endpoints in 680 patients hospitalized with pneumonia and abnormal chest radiographs according to categories of body mass index

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | Death, n (%) | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p-value | Transfer to ICU, n (%) | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p-value | 30-day readmission, n (%) | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 12 (17) | 1.27 (0.58–2.81) | 0.6 | 12 (17) | 0.56 (0.27–1.16) | 0.1 | 5 (7) | 0.87 (0.31–2.45) | 0.8 |

| 18.5–25 | 30 (11) | 1.00 | REF | 66 (24) | 1.00 | REF | 20 (7) | 1.00 | REF |

| 25.1–30 | 19 (11) | 0.98 (0.52–1.88) | 0.9 | 40 (24) | 0.93 (0.58–1.50) | 0.8 | 10 (6) | 0.80 (0.36–1.76) | 0.6 |

| >30 | 6 (4) | 0.31 (0.12–0.78) | 0.01 | 32 (20) | 0.74 (0.45–1.23) | 0.3 | 12 (7) | 1.09 (0.52–2.31) | 0.8 |

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; REF, reference.

Models adjusted for age, functional status, prior pneumococcal vaccination, chest radiograph confirmation and Pneumonia Severity Index.

Discussion

In a cohort of almost 1000 patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, obese individuals had a significantly lower adjusted mortality rate compared with normal weight patients. This association was relatively strong (56% relative reduction in mortality) and robust in sensitivity analyses. Conversely, although underweight patients had the highest unadjusted mortality, after accounting for recent weight loss and severity of disease, this was not statistically significant.

Our results are broadly consistent with other research. In studies of chronic diseases such as coronary artery disease, heart failure and end-stage renal disease, several studies have demonstrated the obesity paradox [25–28]. The data for acute infections such as pneumonia are sparse and less consistent. In a study of 317 patients Corrales Medina et al. [15] reported a 12% relative reduction (adjusted OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81–0.96; p <0.01) in pneumonia-related mortality per unit of BMI although they did not present data according to BMI category. Inoue et al. [14] found BMI >25 kg/m2 to be associated with reduced mortality from pneumonia (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50–0.80; p <0.001) in a cohort of over 100 000 Japanese residents. In a study of 2600 men Lacroix et al. [12] demonstrated an inverse relationship between BMI quartiles and pneumonia-related mortality similar to what we observed. The few studies that have examined pneumonia have been limited by their lack of clinical data or their lack of information with respect to recent weight loss or the fact that their data were drawn from atypical populations [12–15].

If our findings are not the result of chance, what might explain our results? Obese individuals may have less physiological reserve [6] and present to hospital with less severe pneumonia. Our data show lower PSI scores and fewer radiographically confirmed pneumonias in obese individuals, although all of our analyses were adjusted for these variables. Alternately (or additionally), the threshold for admitting an obese patient may be lower and this would yield spuriously lower mortality rates [26]. In our study, this is not likely as diabetes mellitus was the only maldistributed co-morbidity, and obese individuals were on more medications compared with the reference group. Last, higher BMI may directly lead to better outcomes and lower pneumonia-related mortality [12,14,15].

Why might obese patients with pneumonia have a survival advantage? First, obese patients may have increased nutritional reserves, which may help mitigate metabolic and inflammatory stress [8]. Second, some authors have suggested that ‘casting’ of the thoracic cavity (i.e. ‘strapping’ due to relatively increased chest wall adiposity) can reduce mechanical lung injury in the setting of pneumonia and other conditions by reducing transpulmonary pressure-mediated lung damage [29]. Third, although obesity is associated with impaired inflammation in general [4], it is also true that leptin production is increased in obesity and leptin enhances CD4 lymphocyte response towards T helper type 1 cells [8]. Clearly, much work remains to be done to elucidate the potential mechanism for protection related to obesity, especially in the setting of acute infections.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, only 27% of the cohort had BMI measured and documented and we have no information regarding the reasons for (or for not) documenting weight; in general, it is part of routine care. In comparing the characteristics of individuals with missing and available data (Appendix 1), few statistically significant and no clinically important differences were noted. Second, we could not distinguish between lean and adipose tissue or central and peripheral obesity, and we had no direct measure of nutritional reserves. Third, it is possible that the obese patients in our cohort, admitted to hospital with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, did not in fact have pneumonia but instead had less serious respiratory tract infections such as acute bronchitis or were misdiagnosed with pneumonia but had shortness of breath or fever for other reasons. Although chest radiographs are an imperfect reference standard for pneumonia [23], our results were unaltered when we restricted analyses to patients with abnormal chest radiographs demonstrating pulmonary infiltrates.

In conclusion, our study suggests that obese individuals with pneumonia are at significantly and substantially lower risk of mortality than normal weight individuals. Our study adds importantly to the reverse epidemiology literature and we believe it justifies the need to undertake more fundamental and mechanistic work to better understand the reasons for the obesity paradox in pneumonia.

Appendix 2.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of the need for intensive care unit transfer of 907 patients with pneumonia.

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted * odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI group | ||||

| <18.5 | 0.65 (0.34–1.23) | 0.18 | 0.55 (0.28–1.09) | 0.09 |

| 18.5–25 | 1.00 | REF | 1.00 | REF |

| 25–30 | 0.87 (0.58–1.31) | 0.50 | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 0.55 |

| > = 30 | 0.76 (0.50–1.15) | 0.20 | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | 0.26 |

| Age > 65 years | 0.40 (0.29–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.16–0.36) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia Severity Index Class IV/V | 1.81 (1.26–2.60) | 0.002 | 3.34 (2.17–5.12) | <0.001 |

| Impaired function | 1.97 (1.24–3.12) | 0.004 | 1.96 (1.20–3.20) | 0.008 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | 1.93 (1.26–2.97) | 0.003 | 1.79 (1.14–2.81) | 0.01 |

c-statistic = 0.71, p <0.001; Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, p 0.60.

Acknowledgments

Grants were received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) and grants-in-aid from Capital Health, and unrestricted grants from Abbott Canada, Pfizer Canada and Jannsen-Ortho Canada. SRM holds the Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management (Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta) and receives salary support from AHFMR and Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (Health Scholar). DTE receives salary support from AHFMR and Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (Population Health Investigator) and CIHR (New Investigator).

Footnotes

Transparency Declaration

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributions

SRM had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis and will act as the guarantor. All authors participated in study conception, design, interpretation and critical revisions, and approved the final manuscript. SK wrote the initial draft. JKMS and DTE undertook analyses. SRM, DTE, TJM obtained funding and supervised the study. All authors have seen and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Whitlock G, Lewington S, et al. Prospective Studies Collaboration. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The WHO Global Infobase [Internet] 2011 Available from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ [cited August 20th, 2012]

- 3.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity Lancet. 2005;366:1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falagas ME, Kompoti M. Obesity and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:438–446. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baik I, Curhan GC, Rimm EB, Bendich A, Willett WC, Fawzi WW. A prospective study of age and lifestyle factors in relation to community-acquired pneumonia in US men and women. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3082–3088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murugan AT, Sharma G. Obesity and respiratory diseases. Chron Respir Dis. 2008;5:233–242. doi: 10.1177/1479972308096978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele RM, Finucane FM, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U. Obesity is associated with altered lung function independently of physical activity and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:578–584. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falagas ME, Athanasoulia AP, Peppas G, Karageorgopoulos DE. Effect of body mass index on the outcome of infections: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2009;10:280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedlund J, Hansson LO, Ortqvist A. Short- and long-term prognosis for middle-aged and elderly patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: impact of nutritional and inflammatory factors. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:32–37. doi: 10.3109/00365549509018970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lange P, Vestbo J, Nyboe J. Risk factors for death and hospitalization from pneumonia. A prospective study of a general population. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1694–1698. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Balanzo X, Gonzalez CA. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:349–355. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13234999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaCroix AZ, Lipson S, Miles TP, White L. Prospective study of pneumonia hospitalizations and mortality of U.S. older people: the role of chronic conditions, health behaviors, and nutritional status. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:350–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tejera A, Santolaria F, Diez ML, et al. Prognosis of community acquired pneumonia (CAP): value of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) and other mediators of the inflammatory response. Cytokine. 2007;38:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue Y, Koizumi A, Wada Y, et al. Risk and protective factors related to mortality from pneumonia among middleaged and elderly community residents: the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2007;17:194–202. doi: 10.2188/jea.17.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrales-Medina VF, Valayam J, Serpa JA, Rueda AM, Musher DM. The obesity paradox in community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e54–e57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone J, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Jin Y, Marrie TJ. Long-term morbidity and mortality after hospitalization with community-acquired pneumonia: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Balti-more) 2008;87:329–334. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318190f444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrie TJ, Wu L. Factors influencing in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective study of patients not initially admitted to the ICU. Chest. 2005;127:1260–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0012-3692(15)34475-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Blitz S, Rowe BH, Romney J, Marrie TJ. The relation between hyperglycemia and outcomes in 2471 patients admitted to the hospital with community-acquired pneumonia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:810–815. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1255–1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basi SK, Marrie TJ, Huang JQ, Majumdar SR. Patients admitted to hospital with suspected pneumonia and normal chest radiographs: epidemiology, microbiology, and outcomes. Am J Med. 2004;117:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Canada Health Profile [Internet] 2011 Oct; Available from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/health-sante/82-228/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Tab=1&Geo1=HR&Code1=4834&Geo2=PR&Code2=48&Da-ta=Rate&SearchText=Edmonton%20Zone&SearchType=Contains&SearchPR=01&B1=Health%20Conditions&Custom [cited July 12th, 2012]

- 25.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Salahudeen AK, Kilpatrick RD, Horwich TB. Survival advantages of obesity in dialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:543–554. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fonarow GC, Norris CM, McAlister FA. Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;156:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Norris CM, Mullen JC, Pretorius V, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Effect of obesity on short- and long-term mortality postcoronary revascularization: a meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:442–450. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Kronenberg F, Anker SD, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology of dialysis patients and heart failure patients. Semin Nephrol. 2006;26:118–133. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malhotra A. Low-tidal-volume ventilation in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1113–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct074213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]