Abstract

Women may be more vulnerable to certain stress-related psychiatric illnesses than men due to differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis function. To investigate potential sex differences in forebrain regions associated with HPA axis activation in rats, these experiments utilized acute exposure to a psychological stressor. Male and female rats in various stages of the estrous cycle were exposed to 30 min of restraint, producing a robust HPA axis hormonal response in all animals, the magnitude of which was significantly higher in female rats. Although both male and female animals displayed equivalent c-fos expression in many brain regions known to be involved in the detection of threatening stimuli, three regions had significantly higher expression in females: the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), the anteroventral division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTav), and the medial preoptic area (MPOA). Dual fluorescence in-situ hybridization analysis of neurons containing c-fos and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA in these regions revealed significantly more c-fos and CRF single-labeled neurons, as well as significantly more double-labeled neurons in females. Surprisingly, there was no effect of the estrous cycle on any measure analyzed, and an additional experiment revealed no demonstrable effect of estradiol replacement following ovariectomy on HPA axis hormone induction following stress. Taken together, these data suggest sex differences in HPA axis activation in response to perceived threat may be influenced by specific populations of CRF neurons in key stress-related brain regions, the BSTav, MPOA, and PVN, which may be independent of circulating sex steroids.

Keywords: Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, estrous cycle, medial preoptic area, paraventricular nucleus, sexual dimorphism

1

Stress can be an exacerbating or causal factor in the etiology of many diseases, including several psychological disorders. Some of these stress-influenced psychiatric illnesses are at least twice as prevalent in women than men, such as major depression (Linzer et al., 1996; Kessler et al., 2005; Van de Velde et al., 2010) and several anxiety disorders, such as posttraumatic stress and generalized anxiety disorders (Linzer et al., 1996; Stein et al., 2000; Holbrook et al., 2002; Tolin and Foa, 2006; Bekker and van Mens-Verhulst, 2007; Olff et al., 2007; Christiansen and Elklit, 2008; Vesga-López et al., 2008; Ditlevsen and Elklit, 2010). In humans these disorders are associated with dysregulation, either hypo- or hyper-activity, of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis and thus the HPA axis is currently the target of therapeutic treatments for these illnesses (Lanfumey et al., 2008; Lloyd and Nemeroff, 2011). In the brain, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) controls activation of the HPA axis in response to either real or perceived threats, and release of the hormones adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol. If hyperactivity of the HPA axis truly underlies stress-related psychiatric illness in humans, female susceptibility to these illnesses could potentially be explained by differences in HPA axis activation following perceived, or psychological, threats or stressors.

In rats, there is a wealth of evidence that females can have much larger magnitude HPA axis activation to stress than males. Female rats reportedly release more ACTH and corticosterone (CORT) compared to male rats following a wide variety of acute stressful stimuli (Le Mevel et al., 1978; Livezey et al., 1985; Heinsbroek et al., 1991; Aloisi et al., 1994; Handa et al., 1994; Ogilvie and Rivier, 1997; Aloisi et al., 1998; Weinstock et al., 1998; Rivier, 1999; Drossopoulou et al., 2004; Seale et al., 2004; Viau et al., 2005; Larkin et al., 2010). In addition, activation of the PVN is significantly higher in females than males following various acute stressors, as indexed by either mRNA or protein products of the immediate early gene c-fos (Seale et al., 2004; Viau et al., 2005; Larkin et al., 2010). Presumably, gender biased stress-induced activation of the PVN, and subsequent HPA hormone release are the result of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-dependent differences, the primary PVN peptide controlling release of ACTH from the pituitary (at least in rodents). Indeed, basal (Viau et al., 2005) and stress-induced CRF mRNA levels in the PVN have been reported to be higher in female compared to male rats (Aloisi et al., 1998; Iwasaki-Sekino et al., 2009). However, at least one group has reported the opposite effect after restraint stress (Sterrenburg et al., 2012), and Zavala and colleagues (Zavala et al., 2011) reported higher PVN c-fos (FOS) immunoreactivity in male compared to female rats after acute restraint. It remains unclear whether sex differences in PVN activation occurs specifically within CRF, or some other population, of neurons.

Very little research thus far has focused on sex differences in activation of brain regions associated with PVN relative activity following processive stressors, defined as psychological stimuli that activate stress response systems regardless of whether or not the threat is real. However, uncovering how sex might influence these particular pathways may be especially important for understanding sex- and stress-influenced psychiatric disorders in humans. We have previously identified regions that are associated with HPA axis activation to processive stress in male rats using audiogenic stress, including the ventrolateral septum, the anteroventral division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTav), the subiculum, and the medial preoptic area (MPOA), and c-fos mRNA expression in these regions was found to be highly correlated with PVN activity and HPA axis hormone release (Burow et al., 2005). Others have implicated such regions as the medial prefrontal cortex and medial nucleus of the amygdala as limbic structures capable of affecting HPA axis responses to perceived threats (Emmert and Herman, 1999; Herman et al., 2003; Day et al., 2004). Importantly, several studies have shown sex differences in some of these regions. For example, sex differences in activation have been observed after either formalin injection or restraint stress in the septum (Aloisi et al., 1997) and frontal cortex (Figueiredo et al., 2002). Females show less activity in the medial prefrontal cortex after inescapable tailshock than males, despite females having greater HPA axis hormone release following this stressor than males (Bland et al., 2005). Of particular interest however, are potential sex differences in the BSTav and the MPOA that could affect HPA axis activity. Both of these regions have CRF-producing neurons, and they both contain dense numbers of both androgen and estrogen receptors (Simerly et al., 1990). Specifically, CRF-containing neurons in the fusiform nucleus of the BST send direct projections to the PVN (Dong et al., 2001). In addition, a sexually dimorphic population of CRF neurons exists in the MPOA (McDonald et al., 1994; Funabashi et al., 2004), which is a morphologically and functionally sexually differentiated region involved in the control of reproductive behavior containing dense amounts of steroid hormone receptors (Tobet and Hanna, 1997). Furthermore, this region has been found to be the site of inhibitory action of androgens on HPA axis activity in male rats (Viau and Meaney, 1996; Williamson et al., 2010). Indeed, several researchers have named these particular regions as likely candidates for sex-specific influences on stress-induced HPA axis function (Viau, 2002; Herman et al., 2003). However to date, no research has focused on stress-induced sex differences in these areas simultaneously.

Therefore to investigate possible sex differences in stress-induced neurocircuitry following acute stress, we exposed male and female rats to 30 min of restraint. Because many studies have demonstrated estrous cycle influences on both basal (Atkinson and Waddell, 1997) and stress-induced (Viau and Meaney, 1991; Rhodes et al., 2002; 2004; Conrad et al., 2004; Iwasaki-Sekino et al., 2009; Larkin et al., 2010) ACTH and CORT release, we included females in 3 stages of the estrous cycle: diestrus, proestrus, and estrus. In contrast to our previous studies in male rats using noise stress, we used restraint stress in this study due to the large volume of literature examining the effect of sex on responses to this stressor in particular. We first utilized the immediate early gene c-fos as a general marker of neuronal activation, in order to measure stress-induced brain activity across a wide selection of regions with dissimilar neuroanatomical characteristics. We then investigated brain regions that were found to have a sex-specific activation to determine colocalization of CRF with c-fos using dual fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Finally, we manipulated sex steroid levels in females and compared acute stress-induced HPA axis hormone activation in females with prolonged exposure to silastic capsules containing estradiol or vehicle, compared to intact male and female animals.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Experiments 1 and 2: Animals

Young adult (2–3 month old) Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were allowed to acclimate in the colony for at least one week without manipulation upon arrival. All animals were originally group-housed but were singly housed in the same room just prior to stress manipulation (Experiment 1), or following surgery (Experiment 2), and were maintained on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle (lights on at 6 am) under constant temperature and humidity conditions, and were provided access to food and water ad libitum. All experimental manipulations occurred between the hours of 8 am and 12 pm to control for diurnal rhythms of ACTH, CORT, and estradiol. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado at Boulder and conformed to NIH guidelines.

2.2. Experiment 1: Procedure

All females were monitored daily for stage of estrous cycle via vaginal lavage. Only females exhibiting normal 4–5 day cycles were included in this study, and all females were monitored for at least 2 full cycles prior to stressor exposure. All males were handled daily in a similar fashion to control for this manipulation. To increase the likelihood of normal estrous cycling in the female subjects, cages were alternated by sex on racks in the colony room. Males and females predicted to be in each stage of the estrous cycle were run concurrently on each test day, over a total of 5 days. Prior to stressor exposure, animals were habituated to transport in their home cages from the colony to a behavioral testing suite down the hall from the colony room each morning for 5 days. Animals were left in an adjacent room to where restraint took place for 30 min. Similar to the previous 5 days, on the morning of the experiment, males (n = 6) and females that were predicted to be in the following estrous cycle stages: diestrus (n = 9; DI), proestrus (n = 8; PRO), and estrus (n = 6; EST) were transported to the behavioral suite and left untouched for at least 30 min. Animals were weighed, baseline blood samples collected, and then placed into Plexiglas tubes with tails protruding, for a total of 30 min (including basal blood sampling). Due to the significant body weight differences between males and females (data not shown; see Results 3.3), two different sized restrainers were used to achieve similar constraint of the animal within the tube. Males were restrained in tubes that were 20.6 cm in length and 6.3 cm in diameter, and females were restrained in tubes that were 18.1 cm in length and 5.1 cm diameter. The size of all tubes restricted gross movements in all directions, but did not interfere with animals’ breathing. All animals were sacrificed immediately following the 30 min of restraint.

2.3 Experiment 2: Procedure

Experiment 2 was carried out to further explore estrogenic influences on HPA axis responses to restraint stress in our lab. For this experiment, male and female Sprague-Dawley rats were raised in the animal colony at the University of Colorado at Boulder until they were 3 months of age. On days 1 and 2, females were ovariectomized via bilateral incisions and implanted with silastic capsules as described previously (Ström et al., 2008). Briefly, 30 mm long silastic tubing segments (Inner/Outer Diameter: 1.575/3.173 mm, Dow Corning, Fisher Scientific Inc, USA) were filled with 70 μl of either sesame oil vehicle (OVX; n = 10) or 17β-estradiol (E2; 180μg/ml; Sigma) in sesame oil (OVX + E2; n = 10), and were sealed with 5 mm long segments of 2 mm diameter wooden applicator sticks. Other female (intact females; n = 12) and male (intact males; n = 10) rats received sham surgery on the same days: identical bilateral incisions were made into the muscle walls and immediately sutured without removal of any tissues. Other than the day of surgery, all manipulations were performed between 8 am and 12 pm. Animals were given one week to recover from surgery prior to further experimental manipulation. On days 9–14, following the surgical recovery period, rats were habituated to being transported down the hallway from the colony room to a behavioral testing suite. On day 10, prior to being transported to the behavioral suite (8–9 days post-surgery), basal blood samples were taken outside the colony room in which all animals were housed. On day 15 rats were exposed to a loud noise stressor for 30 min (data not shown). On day 17 (15–16 days post-surgery), all animals were again transported from the colony room to the behavioral testing suite and left untouched for at least 15 min, but were then exposed to 30 min of restraint just as in Experiment 1, immediately after which all animals were sacrificed. On the day of restraint males weighed significantly more than females (data not shown), so two different sized restrainers were used as in Experiment 1.

2.4 Experiments 1 and 2: Blood and Tissue Collection

Blood samples before sacrifice were collected from a lateral tail vein. Briefly, animals were removed from their home cages and gently restrained in a towel. A puncture was then made with the corner of a razor blade into one of the lateral tail veins. Samples for ACTH analysis (300–400 μl) were collected into plain glass capillary tubes and placed into chilled tubes containing 15 μl of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; 20 mg/ml). Samples for estradiol and CORT analyses (100–200 μl for experiment 1; 300–400 μl for Experiment 2) were collected into heparinized glass capillary tubes and placed into empty chilled microcentrifuge tubes. The entire procedure lasted less than 5 min per animal to avoid detecting rising hormone levels due to the procedure itself. Whole blood samples were centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 rpm and plasma for each hormone was extracted and stored at −80°C. Following decapitation, blood samples and brain tissue were harvested simultaneously. Trunk blood was collected into chilled EDTA-coated plastic tubes (Vacutainer® EDTA(K2) tubes; BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for determination of ACTH, CORT, and estradiol concentration. Whole blood Vacutainers were then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 2,000 rpm, after which plasma was extracted and stored at −80°C. Brains were rapidly removed, frozen in chilled methylbutane (between −20 and −30°C), and stored at −80°C until further processing.

2.5 Experiments 1 and 2: ACTH Immunoradiometric Assay (IRMA)

Plasma ACTH concentrations were assayed using a commercially available immunoradiometric assay kit (Cat # 27130; DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN, USA); which has a sensitivity of 1.5 pg.ml, and inter- and intra-assay coefficients of ~4.6% and ~ 4.18%, respectively. This IRMA kit recognizes 100% of whole molecule ACTH (detects all 39 amino acids), and as such is very specific, with undetectable crossreactivity for α- and β-MSH, as well as β-Endorphin. All samples from each experiment were analyzed separately within one assay to eliminate interassay variability. The assay was performed according to the kit directions. Briefly, 200 μl of plasma or plasma diluted with zero standard (provided with the kit) was incubated overnight with a 125I-labelled monoclonal antibody specific for ACTH amino acids 1–17, a goat polyclonal antibody specific for ACTH amino acids 26–39, and a polystyrene bead coated with a mouse anti-goat IgG. Only ACTH in the sample with all 39 amino acids bound both antibodies to form an antibody complex on the polystyrene bead. The following day, tubes containing the radioactive beads were washed to remove any unbound reagents and the amount of radioactivity still left on each bead was determined with a gamma counter. The concentration of ACTH for each sample was calculated by fitting values for each sample into a standard curve of known ACTH dilutions processed concurrently.

2.6 Experiments 1 and 2: CORT Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Plasma CORT concentrations were analyzed using a commercially available kit (Cat. # 901-097; Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). This is a highly specific assay (100% cross-recaticvity with CORT, 28.6% with deoxycoticotserone, and 1.7% with progesterone), with a sensitivity of 26.99 pg/ml, and inter-/intra-assay variability of ~ 7.5% and ~ 9.7%, respectively. All samples from each experiment were analyzed within one assay to eliminate interassay variability. The kit directions were followed with the exception of a modification to use a smaller volume of plasma as follows. The steroid displacement reagent (0.5 μl/ml; provided with the kit) was added to the assay buffer. Ten μl of plasma was then diluted 1:50 with the amended assay buffer. The diluted plasma samples were then processed according to the kit directions. This method was found to result in assayed CORT levels equivalent to the method in the kit directions (data not shown). Briefly, plasma samples and diluted CORT standards were incubated in a 96-well plate coated with anti-sheep antibody raised in donkey, together with CORT with a covalently attached alkaline phosphatase molecule, and a sheep polyclonal antibody for CORT. After a 2 hr incubation period the plate was washed to remove all unbound reagents and a substrate was added. After 1 hr the color reaction was stopped and the intensity of color in each well was analyzed at 405 nm using a microplate reader (Biotek EL808; Winooski, VT, USA). The concentration of CORT for each sample was calculated by fitting unknown values into a standard curve of known CORT dilutions processed concurrently.

2.7 Experiments 1 and 2: Estradiol Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

Plasma estradiol concentrations were determined using a double-antibody radioimmunoassay kit (Cat # KE2D1; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA). The antiserum used in this kit is highly specific for estradiol (100% detection of 17β-estradiol) and has virtually undetectable crossreactivity with other naturally occurring steroids; the highest occurring crossreactivity being with estrone at 12.5%. The sensitivity of this assay is 1.4 pg/mL, has intra-assay variability of 4–14% and inter-assay variability of 3.5–5.5%. However, all samples were run in a single assay to eliminate interassay variability. The assay was performed according to kit directions. Briefly, samples, calibrators, and controls were first incubated with anti-estradiol serum for 2 hr, after which 125I-labeled estradiol is added which competes for antibody sites with estradiol already in the tubes for 1 hr. Separation of the bound estradiol from the free estradiol was then achieved by a PEG-accelerated double-antibody method. Then, the antibody-bound fraction was precipitated by centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min, the supernatant was aspirated, and the remaining pellet was counted on a gamma counter. Unknown concentrations of estradiol in the samples were then calculated using a calibration curve run concurrently.

2.8 Experiment 1: Radioactive In Situ Hybridization

The method for in situ hybridization has been described previously (Day et al., 2005). Briefly, whole brains stored at −80°C were mounted on chucks at −20°C. Ten micrometer thick sections were cut on a cryostat (Model 1850; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), thaw-mounted onto polylysine-coated slides and stored at −80°C. Slides were taken from storage and immediately fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hr, acetylated in 0.1M triethanolamine (pH 8.0) with 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min, dehydrated through graded ethanols to 100% and air dried. A riboprobe against c-fos mRNA (680 mer; courtesy of Dr. T. Curran, St. Jude Children’s Hospital, Memphis, TN) was generated using standard transcriptional methods and labeled with 35S-UTP (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Brain sections were hybridized overnight at 55°C with the riboprobe diluted to 1–3 ×106 c.p.m. per 70 μl in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 3X saline sodium citrate, 50mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 1X Denhardt’s solution, 0.1 mg/ml yeast tRNA, and 10mM dithiothreitol. The following day, the probe was washed from the slides, and they were then treated with RNase A (200 μg/ml; pH 8.0) at 37°C for 1 hr, washed to a final stringency of 0.1X saline sodium citrate for 1 hr at 65°C, dehydrated again in graded ethanols to 100%, and air dried. Slides were then exposed to X-ray film (BioMax-MR; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 7–12 days. Films were then analyzed as described below.

Levels of c-fos mRNA were analyzed by computer-assisted optical densitometry by an experimenter blind to the treatment conditions. Images of each individual brain section were captured digitally (CCD camera, model XC-77; Sony, Toyko, Japan), and digital images were then analyzed using Scion Image (Version 4.03 for Windows; ScionCorp). First, the relative optical density of the x-ray film was determined using a macro within Scion Image (written by Dr. S. Campeau) which allowed the automatic determination of a signal above background. Specifically, for each section, a background sample was taken over an area of white matter, and the signal threshold was set as 3.5 standard deviations above the mean gray value of the background. The remaining pixels above this threshold were then analyzed within the brain region of interest. It should be noted that although background criteria were relatively stringent, this method still results in a few pixels above background in areas on the x-ray film not on the brain section, indicating that even weak intensity mRNA signal on the tissue is detected. For consistency, a different template was created for each brain region, and was placed using anatomical landmarks based on the white matter distribution of the unstained tissue, according to a standard rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). The number of pixels above background was multiplied by the signal above background to give an integrated density value for both hemispheres throughout the rostral-caudal extent of each brain region of interest. This method has been reported to reflect both the number of cells expressing mRNA and the expression level per cell, as determined by cell and grain counts of emulsion-dipped slides (Day et al., 2005). Therefore, differences in this measure could reflect changes in cell number and/or mRNA expression levels within cells. The mean integrated density for each animal was then calculated by averaging the highest 2 or 3 values for each hemisphere depending on the brain region resulting in a single value for each animal representing the peak of c-fos mRNA expression for each brain region of interest.

2.9 Experiment 1: Dual Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

In a subset of animals, adjacent sections to those used for radioactive in situ hybridization determination of c-fos mRNA expression were also analyzed using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). This procedure allowed for colocalization of c-fos and CRF mRNA expression within the same cells within brain regions where a sex difference was seen using traditional radioactive in situ hybridization analysis of c-fos mRNA expression. Initial slide processing and probe hybridization was performed using the same procedure described above for radioactive in situ hybridization, except for the following differences. Riboprobes against c-fos mRNA (described above) or CRF mRNA (770 mer; cDNA provided by Dr. R. Thompson at the University of Michigan) were both synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase with fluorescein-12-UTP and digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), respectively. A total of 6–8μl of each labeled probe was added to each slide in hybridization buffer (details above) containing 20mM DTT. After the high stringency wash, slides were placed into 0.05M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4; PBS) overnight at 4°C. On the following day, endogenous peroxidase was quenched in 2% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation, after which slides were washed with 1X Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 (pH 7.5; TBS-T). After a 30 min incubation at room temperature in blocking buffer (FP1012; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), slides were incubated with anti-fluorescein-HRP (1:250 in blocking buffer, 80μl/slide; NEF710, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) in humidified chambers for 30 min. After removing coverslips and washing slides in TBS-T, the fluorescein-UTP-Fos complex was detected using a tyramide signal amplification kit with fluorescein as the fluorophore for 1 hr at room temperature in a humidified chamber (1:100, 80μl/slide; TSA-Plus Kit, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Slides were washed in TBS-T, rinsed in 1X TBS (pH 7.5; no Tween) to remove residual detergent, and transferred to PBS. After repeating the endogenous peroxidase quenching procedure, slides were washed with TBS-T, and then incubated with anti-digoxigenin-peroxidase (1:500 in blocking buffer, 80μl/slide; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) for 30 min at room temperature in humidified chambers. After rinsing with TBS-T, the digoxigenin-UTP-CRF complex was then visualized using Cyanine-3 as the fluorophore as above. After the final tyramide amplification similar to that described above, slides were rinsed with TBS-T, then TBS, and then coverslipped with Vectashield hardset mounting medium (containing DAPI as a counterstain; H-1500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Control slides of the same tissue run without addition of probe or without amplification resulted in sections with no detectable fluorescence.

Cells containing fluorescent markers for c-fos and CRF mRNA were visualized with an upright fluorescence microscope (AxioImager Z1; Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY, USA). Single- and double-labeled cells were counted using AxioVision software (v. 4.8.2) tools ‘aligned rectangle’ placed according to landmarks seen using DAPI counterstaining in order to analyze a consistently sized area between animals, and the ‘measure events’ tool to prevent multiple counts of the same cell.

2.10 Experiment 1: Statistical Analysis

Body weight data for Experiment 1 were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with males and fe males in each stage of the estrous cycle. Baseline and stress-induced ACTH and CORT concentrations were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA, and independent samples t-tests were run on hormone data before and after stress to determine the source of significant interactions. Endogenous estradiol concentrations in female rats were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, and an independent samples t-test was used to test for a sex difference. To test the possible effect of the estrous cycle on c-fos mRNA expression across all brain regions, data in female rats were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. To test whether a significant sex difference in c-fos mRNA expression levels across brain regions, log-transformed data were analyzed using independent samples t-tests. Post-hoc analyses, when necessary, were performed using Tukey’s HSD multiple means comparisons. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for analysis of body weight and hormone data. To further reduce the possibility of Type I error when analyzing c-fos mRNA expression data from several brain regions, statistical significance for these tests was set at p < 0.01. FISH-derived cell counts were first analyzed with one-way ANOVAs in females only to test for estrous cycle effects. Sex differences in these data were then analyzed with subsequent t-tests, with significance set at a p value of 0.05.

2.11 Experiment 2: Statistical Analysis

ACTH and CORT data were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA. Significant main effects in the repeated measures ANOVAs were explored further with one-way ANOVAs. Estradiol concentrations 8–9 days post-surgery and 15–16 days post-surgery were analyzed via one-way ANOVAs separately. Further post-hoc analyses, if necessary, were performed using Tukey’s HSD multiple means comparisons. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all statistical tests for experiment 2. PASW Statistics (formerly SPSS, version 18 for Windows) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: HPA Axis Hormones

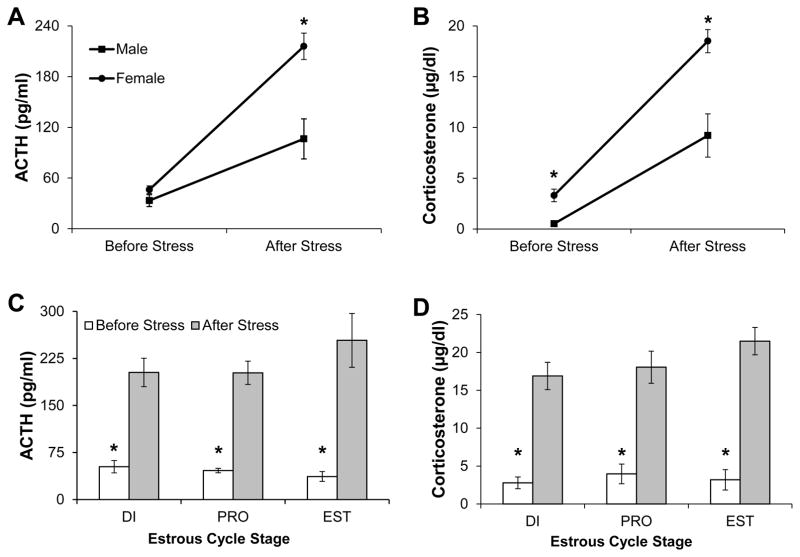

Figure 1 displays HPA axis hormone plasma concentrations immediately prior to and immediately following, 30 min of restraint. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed that restraint significantly increased ACTH levels in both males and females as reflected by a main effect of stress (F1,27 = 46.54, p < 0.001; Fig 1A). In addition, females had higher ACTH levels compared to males, as revealed by a significant main effect of sex (F1,27 = 13.59, p = 0.001). There was also a significant stress by sex interaction (F1,27 = 7.39, p = 0.01). Post-hoc analyses revealed that females had significantly higher concentrations of ACTH only after stress (t(27) = 3.32, p < 0.01) and did not differ significantly before stress (t(27) = 1.33, p = 0.19). Restraint also significantly increased CORT concentration in both males and females, as revealed by a significant main effect of stress (F1,27 = 81.43, p < 0.001; Figure 1B). Overall, females also had significantly higher concentrations of CORT compared to males (F1,27 = 17.12, p < 0.001). In addition, there was a significant stress by sex interaction on CORT concentration (F1,27 = 6.04, p = 0.02). Post-hoc analyses revealed that although females had significantly higher CORT concentrations before and after stress, the effect of sex on CORT concentration was larger after restraint (t(27) = 3.73, p = 0.001) than before restraint (t(27) = 2.2, p = 0.03).

Figure 1.

HPA axis hormone concentrations immediately prior to (Before Stress) and following (After Stress) 30 min of restraint stress in Experiment 1. All values represent group means ± 1 SEM. (A,B) Plasma concentrations of ACTH (A) and CORT (B) in intact male and female rats. * P < 0.05 compared to males at the same timepoint. (C,D) Plasma concentrations of ACTH (C) and CORT (D) in females across three stages of the estrous cycle. *P < 0.05 compared to stress condition within the same estrous cycle stage.

Restraint significantly increased ACTH concentration (F1,20 = 101.62, p <0.001; Fig 1C) and CORT concentration (F1,20 = 153.49, p <0.001; Fig 1D) in all females. However, there was no main effect of estrous cycle stage on either ACTH (F2,20 = 0.63, p = 0.54) or CORT (F2,20 = 1.06, p = 0.37) concentrations, and no significant stress by estrous cycle interactions on either hormone concentration (p’s > 0.05).

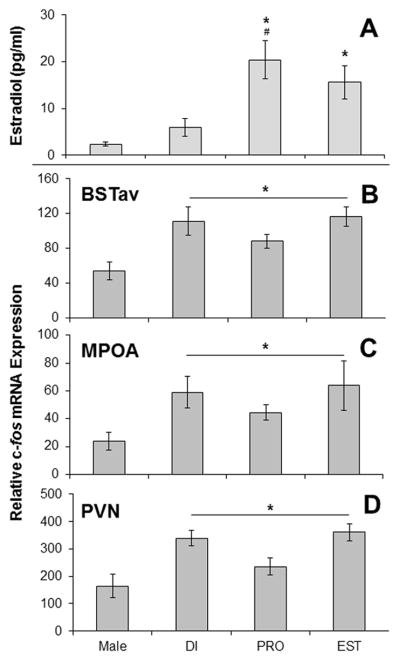

3.2. Experiment 1: Plasma Estradiol Concentration

Figure 2A displays plasma estradiol concentrations for all groups from Experiment 1. There was a significant effect of group (F3,25 = 7.99, p = 0.001) on estradiol concentration. Post-hoc analyses revealed that females in proestrus and in estrus had significantly higher estradiol concentrations than male rats (p’s < 0.05), and females in proestrus also had significantly higher estradiol concentration than females in diestrus (p = 0.005). Females in proestrus did not differ significantly from females in estrus (p = 0.68), and females in diestrus did not differ significantly from males (p = 0.82).

Figure 2.

All values represent group mean ± 1 SEM. A: Plasma estradiol concentrations on the day of stress in Experiment 1. *P < 0.05 compared to males. #P < 0.05 compared to DI. B,C,D: Relative c-fos mRNA expression immediately after stress in Experiment 1 within the BSTav (B), the MPOA (C), and the PVN (D). *p < 0.05 for all females compared to males. Abbreviations: BSTav – Bed Nucleau of the Stria Terminalis; MPOA – Medial Preoptic Area; PVN – Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus; DI – diestrus; PRO – proestrus; EST – estrus.

3.3. Experiment 1: In situ Hybridization c-fos mRNA Expression

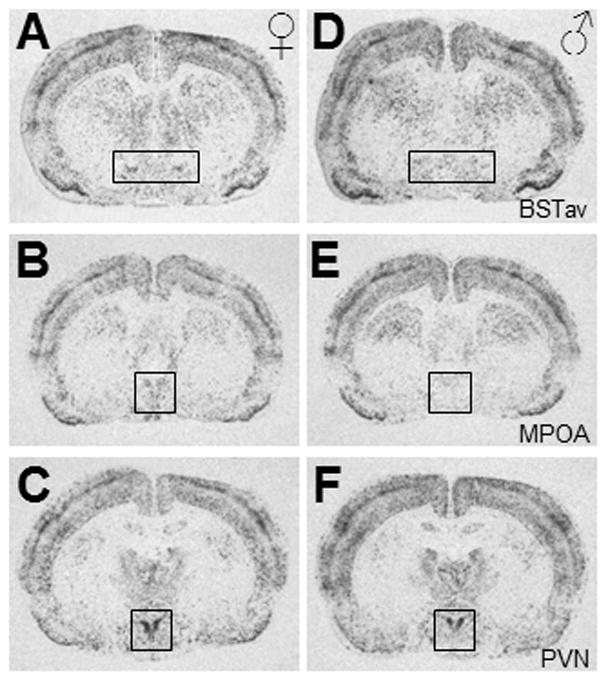

As expected, female rats displayed c-fos mRNA expression in all of the regions analyzed, indicating a qualitatively similar pattern of brain activation in male and female rats overall in response to restraint stress. Within females only, there was no effect of the estrous cycle on c-fos mRNA expression in any brain region analyzed, and so data were pooled for females across estrous cycle. Body weight analysis revealed a main effect of sex (F3,25 = 129.73, p < 0.001; data not shown), and post-hoc tests verified that males weighed significantly more than females in each stage of the estrous cycle (p’s < 0.001), however there was no effect of estrous cycle in females alone (p’s > 0.05; data not shown). Due to this difference in body weights, several brain regions were analyzed which could reflect the amount of somatosensory processing induced by restraint stress: the cuneate nucleus within the brainstem (p = ), the ventroposterolateral and ventroposteromedial nuclei of the thalamus (p = ), and the barrel field region of the primary somatosensory cortex (p = ). The remaining regions were analyzed due to their high correlations with stress-induced ACTH and c-fos mRNA expression in the PVN as demonstrated previously in male rats following loud noise stress (Burow et al., 2005), or due to their reported involvement in stress responses. No significant effect of sex was found in the following regions (p’s > 0.01; data not shown): the anterior medial prefrontal cortex, the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex, the infralimbic region of the prefrontal cortex, the oval nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the lateral septum, the septohypothalamic area, the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, the medial nucleus of the amygdala, and the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala. However, female rats did display significantly higher c-fos mRNA expression compared to male rats in the following brain regions: the BSTav (t(27) = 4.2, p < 0.001; Figure 2B), the MPOA (t(27) = 3.3, p = 0.002; Figure 2C), and the PVN (t(27) = 3.8, p = 0.001; Figure 2D). Note that the pattern of c-fos mRNA expression seen across the estrous cycle in these 3 regions (Figure 2B–D) does not mimic plasma estradiol levels (Figure 2A). Figure 3 depicts representative photomicrographs of brain regions from both sexes that exhibited higher c-fos mRNA expression in females compared to males.

Figure 3.

Representative photomicrographs displaying the effect of sex on c-fos mRNA expression of female (A,B,C) and male (D,E,F) brains; within the anteroventral region of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTav; A,D), the medial preoptic area (MPOA; B,E), and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN; C,F).

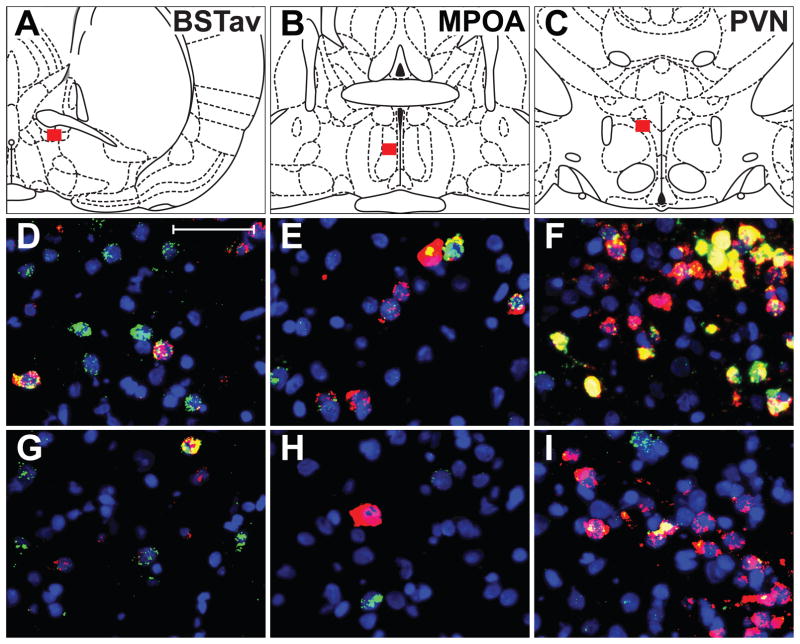

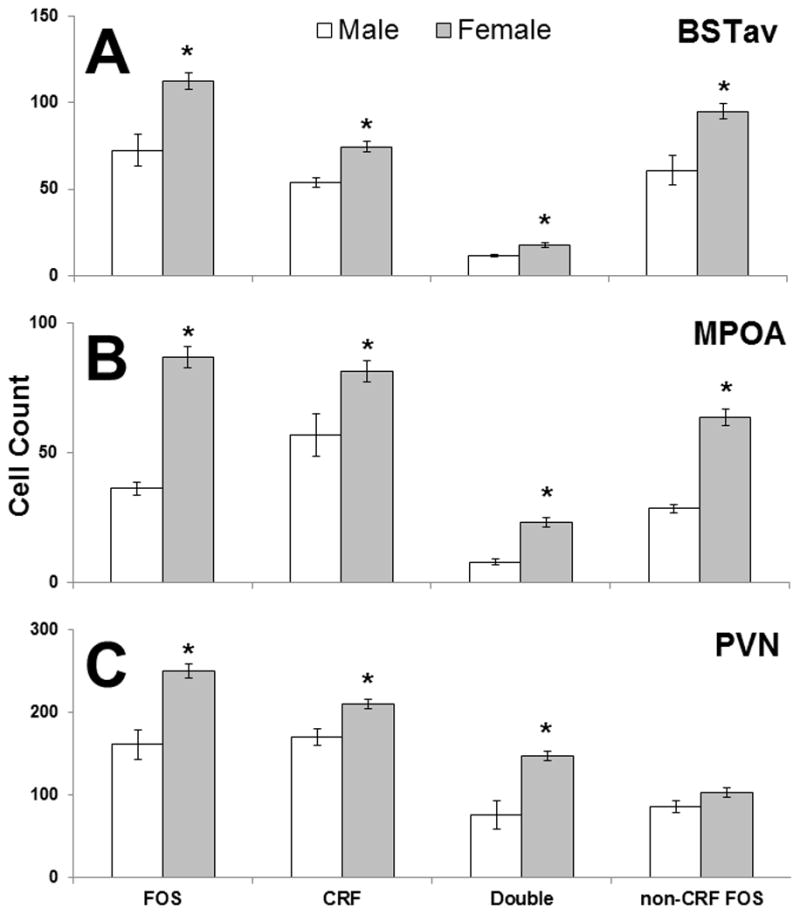

3.4. Experiment 1: Dual FISH CRF and c-fos mRNA expression

Adjacent sections from within the regions where a significant effect of sex was seen with in situ quantification of c-fos mRNA alone (BSTav, MPOA, and PVN) within a subset of rats from Experiment 1 were also analyzed for double-labeling of CRF and c-fos mRNAs. Figure 4 displays examples of FISH labeled brain sections from areas analyzed, with red boxes in A–C approximating the Bregma locations of photomicrographs in D–I (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Figure 4 panels D, E, and F are photomicrographs taken from a representative female brain, and panels G, H, and I exhibit the same for a representative male brain. In this figure, blue color represents a fluorescent DNA marker (DAPI) which displays cell nuclei, the color red represents CRF mRNA single-labeling, a green color represents single-labeling for c-fos mRNA, and the color yellow indicates areas of overlapping green and red, which represents cells double-labeled for CRF and c-fos mRNAs. Qualitatively, the BSTav and MPOA contained not only drastically fewer labeled cells as the PVN, but the cells in these regions were also much more sparse compared to the densely packed cells of the PVN, although all 3 regions exhibited cells labeled green, red, and yellow.

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs of c-fos and CRF mRNA labeled neurons using dual FISH in the BSTav (A,D,G), MPOA (B,E,H) and PVN (C,F,I). A,B,C: Representative bregma images with red boxes showing the approximate location of photomicrographs in D–I. D,E,F: Magnified images from a female brain; Scale bar in D = 50μm. G,H,I: Images of a representative male brain at same magnification as in D,E,F. Blue=DAPI stain for nuclei; Red=CRF mRNA; Green=c-fos mRNA; Yellow= overlap of CRF and c-fos mRNA.

No effect of the estrous cycle was observed on any FISH measure quantified (p’s > 0.05; data not shown), therefore all subsequent analyses for sex differences compared all females collapsed across estrous cycle to males. As demonstrated in Figure 5, females had significantly more c-fos-labeled cells in the BSTav (t(18) = 3.8, p < 0.01), MPOA (t(18) = 6.0, p < 0.0001), and PVN (t(18) = 4.3, p < 0.001). In all three of these regions, the number of cells labeled for c-fos mRNA was approximately 2-fold higher in the female compared to male brain, which was qualitatively similar to the increased expression observed via in situ hybridization with radioactive nucleotides (see Figure 2 and Results Section 3.3). Significantly more CRF-labeled neurons were also observed in the female BSTav (t(18) = 3.2, p < 0.01), MPOA (t(18) = 2.7, p < 0.05), and PVN (t(18) = 3.0, p < 0.01) compared to the male brain. Importantly, the number of CRF and c-fos double-labeled neurons was also significantly higher in the female BSTav (t(18) = 2.4, p < 0.05), MPOA (t(18) = 4.3, p < 0.001), and PVN (t(18) = 5.1, p < 0.0001) compared to the male brain. Finally, the female BSTav (t(18) = 3.5, p < 0.01) and MPOA (t(18) = 5.3, p < 0.001) had significantly more c-fos-labeled neurons that did not contain CRF compared to the male brain, but there was no significant sex difference in this cell type in the PVN (p > 0.05). Indeed, only within the PVN did females exhibit a higher percentage (t(18) = 3.6, p < 0.01) of c-fos-labeled neurons containing CRF than males (data not shown).

Figure 5.

The effect of sex on CRF and c-fos mRNA containing cells as visualized by FISH in Experiment 1, and colocalization of both genes in the BSTav (A), the MPOA (B), and the PVN (C) after 30 min of restraint. * = p < 0.05 compared to males.

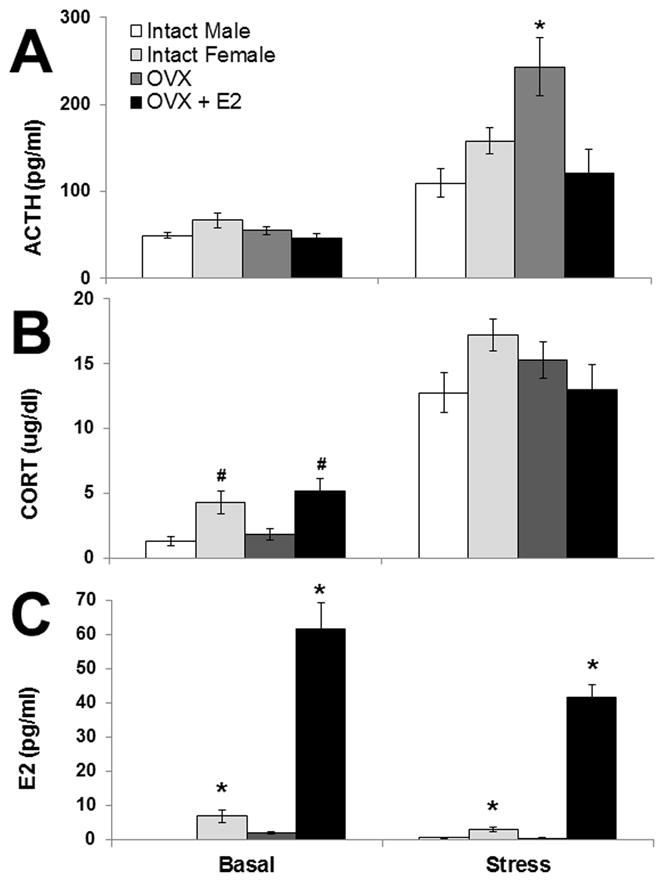

3.5. Experiment 2

All data from Experiment 2 are presented in Figure 6. Repeated measures ANOVAs on plasma hormone concentrations revealed that restraint stress significantly increased both ACTH (F1,38 = 78.88, p < 0.001; Figure 6A) and CORT concentrations (F1,38 = 190.69, p < 0.001; Figure 6B). A significant interaction between stress condition and treatment group existed for ACTH concentrations (F3,38 = 5.88, p = 0.002), and post-hoc tests revealed a significant effect of group only after stress (F3,38 = 6.4, p = 0.001). Specifically, OVX females had significantly higher ACTH concentration than all other groups following restraint stress (p’s < 0.05), but none of the other groups differed significantly from each other (Figure 6A). There was a significant main effect of treatment group on basal (F3,38 = 3.34, p = 0.03), but not stress-induced CORT concentrations (Figure 6B). Specifically, intact females and OVX + E2 females had significantly higher basal CORT concentrations than males, and OVX + E2 females were also significantly higher than OVX females (p’s < 0.05). Male and OVX females’, as well as intact and OVX females’ CORT concentrations did not differ significantly (p’s > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Experiment 2: Plasma hormone concentrations (means ± 1SEM) from intact males (n = 10) and females (n = 12) given sham surgery, and ovariectomized females with (OVX + E2; n = 10) or without (OVX; n = 10) estradiol replacement at baseline (Basal) and after 30 min of restraint (Stress). * = p < 0.05 compared to all other groups within the same stress condition. # = p < 0.05 compared to intact males and OVX females within that stress condition.

Ovariectomy alone or with estradiol replacement had a robust effect on estradiol concentrations (Figure 6C). Estradiol concentrations in male rats were only analyzed following restraint stress, due to the assumed stability of the concentration of this hormone in these animals. One week after ovariectomy (Basal), there was a significant effect of treatment group on estradiol concentrations (F2,29 = 59.90, p < 0.001). Ovariectomy significantly decreased estradiol concentration compared to intact females (p = 0.02), whereas ovariectomy with estradiol replacement (OVX + E2) significantly increased estradiol concentrations compared to OVX and intact females (p’s < 0.001). Following restraint stress (15–16 days post-surgery; Stress Group), there was still a significant effect of treatment group on estradiol concentrations (F3,38 = 113.19, p < 0.001). OVX + E2 females had significantly higher estradiol concentrations than all other groups, and intact females also had significantly higher estradiol concentrations than males and OVX females (p’s < 0.001). Males and OVX females did not have significantly different estradiol concentrations (p > 0.05). In the intact females only (n=12), overall there was no significant effect of stage of estrous cycle on plasma ACTH, CORT or E2 (p’s > 0.05; data not shown).

4. Discussion

The fact that HPA axis activation in response to a variety of stressful stimuli can be affected by sex and sex steroids is well established; the exact mechanism by, and level at, which this can occur remains obscure. The present study focuses on the forebrain neural circuit associated with stress-induced HPA axis activation, whether sex differences in stress-induced HPA axis hormone release are accompanied by differences in regulation of processive stress, and the extent to which HPA axis hormone release in females can be attributed to circulating endogenous or exogenous sex steroids. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated sex differences in extended neural circuits, and specifically extra-PVN CRF populations thought to influence subsequent HPA axis responses following acute processive stress. Similar to previous findings using restraint (Seale et al., 2004; Iwasaki-Sekino et al., 2009; Larkin et al., 2010), females in the present study had significantly higher HPA axis hormone induction in addition to significantly higher activation of the PVN compared to male rats. In addition to central HPA axis differences, many regions that were previously linked to HPA axis activation following processive stress in male rats (Campeau and Watson, 1997; Burow et al., 2005) also displayed activation in the female brain, including the lateral septum, septohypothalamic area, infra- and pre-limbic regions of the prefrontal cortex, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, and several stress-responsive amygdaloid nuclei, indicating that the pattern of activation in the female brain in response to stress is qualitatively similar to that seen in the male brain. Since we have previously reported that c-fos mRNA expression in the anteroventral region of both the BST and the MPOA correlate highly with measures of HPA axis activation following acute stress in male rats (Burow et al., 2005), we expected that these two regions specifically might be contributing to sex differences in the magnitude of HPA axis responses, and our data support this hypothesis.

The generally accepted, current hypothesis of sex differences in stress-induced HPA axis function is that estrogens stimulate, and androgens inhibit, this neuroendocrine axis by directly affecting its central effector, the PVN (Bohler et al., 1990; Viau and Meaney, 1991; Vamvakopoulos and Chrousos, 1993; Patchev et al., 1995; Alves et al., 1998; Laflamme et al., 1998; Roy et al., 1999; McCormick et al., 2002; Lunga and Herbert, 2004; Figueiredo et al., 2007; Larkin et al., 2010). It is also possible that sex steroids indirectly affect HPA axis function due to dense numbers of estrogen and androgen receptors in stress-responsive brain regions other than the PVN (Laflamme et al, 1998; Ostlund et al., 2003; Bingham et al, 2006; Williamson and Viau, 2007; Byrnes et al., 2009; Williamson et al., 2010) through regions such as the BSTav and MPOA, regions which both send direct projections to the PVN (Cullinan et al., 1993; Campeau and Watson, 2000; Dong et al, 2001; Forray and Gysling, 2004; Radley et al., 2009; Radley and Sawchenko, 2011). However, in agreement with lack of estrous cycle effects on stress responses that have been reported (Guo et al., 1994; Rivier, 1999; Bland et al., 2005), no effect of estradiol on HPA axis function was observed under the current conditions. If estradiol had a truly augmenting activational effect on stress-induced HPA axis activation, females in PRO, with the highest estradiol concentrations, would be expected to have the highest HPA axis activity, as well as more c-fos and CRF double-labeled neurons in the PVN, but they did not differ significantly from females in other estrous cycle stages on any of these measures. Estrous cycle also did not affect any measures in PVN afferent regions analyzed here, the BSTav and MPOA. Experiment 2 targeted higher concentrations of this hormone that can be seen on the afternoon of proestrus in normally cycling females (Bridges and Byrnes, 2006; Strom et al, 2008), although these females received constant exposure to this normally fluctuating hormone. Contrary to estradiol augmenting HPA axis responses, ovariectomy significantly increased stress-induced ACTH concentrations, and HPA axis hormone induction in females given estradiol did not differ significantly from males. At least one study has demonstrated an inhibitory effect of either estradiol alone, or estradiol in conjunction with progesterone administration on restraint stress-induced ACTH secretion (Young et al., 2001), and this, along with our data, conflicts with other published reports (Viau and Meaney, 1991; 2004). Estradiol administered after an extended hormonal deprivation period induced by ovariectomy can suppress both stress-induced HPA axis hormone induction and Fos labeling in the PVN (Dayas et al., 2000), and even PVN CRF mRNA expression (Grino et al., 1995). It is possible that activational effects of estradiol can only be seen in the context of normal underlying background levels of estradiol, and possibly also progesterone, and this idea has been suggested by others (Viau and Meaney, 2004). However, data from intact females presented here provide no evidence for activational effects of female sex steroids on central HPA axis neurocircuitry following acute stress. This leads to the conclusion that circulating sex steroids in females may not always play a significant role in the magnitude of stress-induced HPA axis responses.

Our data do support the hypothesis that sex may affect development (i.e. the organization) of stress neurocircuitry, since overall female compared to male rats exhibited higher c-fos mRNA expression in several brain regions, despite no evidence of activational effects of circulating sex steroids (McCormick et al., 1998; Berenbaum and Beltz, 2011). Not only did females overall exhibit significantly more single-labeled FOS and CRF neurons within the PVN, but also significantly more neurons double-labeled with both FOS and CRF in this region. Furthermore, the augmented number of activated neurons in the female PVN can be attributed to increased activation of specifically CRF-producing neuroendocrine cells, as there was no significant sex difference in the number of non-CRF-containing cells double-labeled with FOS, and the percentage of FOS-labeled neurons also labeled with CRF was significantly higher in the female PVN. Zavala and colleagues (2011) found no effect of sex in cells containing both FOS and AVP, but did observe that females had significantly higher FOS in cells that also contained glucocorticoid receptors, which mimics the pattern of FOS and CRF co-expression observed here. Because almost all CRF-expressing neurons in the medial parvocellular PVN also express glucocorticoid receptors (Liposits et al, 1987; Ceccatelli et al, 1989), the results of Zavala et al (2011) are likely synonymous with these results.

Lesion studies in male rats support the idea that anteroventral nuclei of the BST mediate some excitation of the HPA axis (Choi et al., 2007; 2008), and because we observed significantly more cells expressing c-fos mRNA in this region in females, this is a potential mechanism contributing to augmented HPA axis hormone release following stress in females. Chemoarchitectural analysis of the male BST illustrates the fusiform nucleus as having the most dense population of CRF neurons within the anteroventral region, in stark contrast to the surrounding nuclei (Ju et al., 1989), and we demonstrate a significantly larger population of this cell type in this region in females compared to males. CRF neurons in the BSTav receive direct innervations from both serotonin (Phelix et al., 1992) and norepinephrine (Phelix et al., 1994) cell groups, so the observed increased size of this cell population in the BSTav might reflect increased innervation of the female BSTav from serotonin and/or norepinephrine cell groups. Further, given the important role of the BST in anxiety, it is possible that these results could have important implications for sex differences in anxiety-like behavior, and not just for HPA axis function (Toufexis 2007; Walker et al., 2009). In addition to females displaying a more activated BSTav, we also observed higher stress-induced activation of the female MPOA, and this sex difference could also contribute to the observation of higher HPA axis hormone release in female compared to male rats. Here we also confirmed previous reports of a larger population of CRF neurons within the female MPOA (McDonald et al., 1994; Funabashi et al., 2004), and the role of these cells could have important function in stress and/or anxiety responses. It should be noted that the majority of activated cells in the female BSTav and MPOA occurred mostly in cells that do not contain CRF, and the neurochemical phenotype of these cells remains to be determined. Higher stress-induced activation of these regions in the female brain may underlie sex differences in HPA axis function, most likely through a non-CRF cell population.

CONCLUSION

In summary, these results demonstrate that HPA axis responses to acute restraint stress are affected by sex in a complex way, and that regions outside of the PVN should be considered when exploring sex differences in brain activation following acute stress. Following restraint, similar stress responsive neurocircuitry is activated in the female compared to male brain, although the magnitude of this activation in certain brain regions is gender specific, despite displaying similar activation of somatosensory regions likely to be involved in the perception of restraint. Females were found to have more CRF-producing and more activated neurons in three brain regions: the BSTav, the MPOA, and PVN, areas known to be involved in the perception of threat and that are likely candidates for gender-specific stress responses, and increased activation in the female PVN occurs specifically within CRF-containing neurons. Furthermore, this study suggests that endogenous or exogenous sex steroid hormones do not significantly and consistently contribute to the magnitude of HPA axis responses to restraint stress. Finally, it is possible that different types of stressors, or even different lab procedures for the same stressor could result in differential sex differences in HPA axis responses, and analysis of stress-induced activation from a wider perspective of brain neurocircuitry may aid in understanding the nature of sex effects on stress responses in general.

Highlights.

Similar qualitative stress-induced neurocircuitry activation in male and female brain

Females have higher activation of PVN, BST, and MPOA after restraint stress

Females have higher stress-induced activation of CRF circuitry

Estradiol doesn’t always augment stress-induced HPA axis activity

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 MH077152 awarded to S. Campeau. The authors would like to thank Dr. Robert Spencer (University of Colorado at Boulder, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience) for generously providing the authors with the restraint tubes used in this experiment and for his invaluable support of this work. The authors would also like to thank Jon Roberts (University of Colorado at Boulder, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Staff member) for providing technical assistance with Figure 4.

Abbreviations

- 3V

3rd ventricle

- ac

anterior commissure

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BSTav

anteroventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- CORT

corticosterone

- CRF

corticotropin releasing factor

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

- DI

diestrus

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- E2

17β-estradiol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EST

estrus

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FOS

c-fos

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- MPOA

medial preoptic area

- OVX

ovariectomized

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PRO

proestrus

- PVN

paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

- TBS-T

tris-buffered saline containing tween-20

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aloisi AM, Albonetti ME, Carli G. Sex differences in the behavioural response to persistent pain in rats. Neurosci Letters. 1994;179:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi AM, Zimmermann M, Herdegen T. Sex-dependent effects of formalin and restraint on c-fos expression in the septum and hippocampus of the rat. Neurosci. 1997;81:951–958. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi AM, Ceccarelli I, Lupo C. Behavioural and hormonal effects of restraint stress and formalin test in male and female rats. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves SE, Lopez V, McEwen BS, Weiland NG. Differential colocalization of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) with oxytocin and vasopressin in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the female rat brain: an immunocytochemical study. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:3281–3286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson HC, Waddell BJ. Circadian variation in basal plasma corticosterone and adrenocorticotropin in the rat: sexual dimorphism and changes across the estrous cycle. Endocrinol. 1997;138:3842–3848. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker MH, van Mens-Verhulst J. Anxiety disorders: sex differences in prevalence, degree, and background, but gender-neutral treatment. Gender Med. 2007;4(Suppl B):S178–S193. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum SA, Beltz AM. Sexual differentiation of human behavior: Effects of prenatal and pubertal organizational hormones. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:183–200. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B, Williamson M, Viau V. Androgen and estrogen receptor-beta distribution within spinal-projecting and neurosecretory neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the male rat. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:911–923. doi: 10.1002/cne.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland ST, Schmid MJ, Der-Avakian A, Watkins LR, Spencer RL, Maier SF. Expression of c-fos and BDNF mRNA in subregions of the prefrontal cortex of male and female rats after acute uncontrollable stress. Brain Res. 2005;1051:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohler HC, Zoeller RT, King JC, Rubin BS, Weber R, Merriam GR. Corticotropin releasing hormone mRNA is elevated on the afternoon of proestrus in the parvocellular paraventricular nuclei of the female rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1990;8:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges RS, Byrnes EM. Reproductive experience reduces circulating 17beta-estradiol and prolactin levels during proestrus and alters estrogen sensitivity in female rats. Endocrinol. 2006;147:2575–2582. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow A, Day HE, Campeau S. A detailed characterization of loud noise stress: Intensity analysis of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis and brain activation. Brain Res. 2005;1062:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes EM, Babb JA, Bridges RS. Differential Expression of Oestrogen Receptor α Following Reproductive Experience in Young and Middle-Aged Female Rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:550–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau S, Watson SJ. Neuroendocrine and behavioral responses and brain pattern of c-fos induction associated with audiogenic stress. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:577–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau S, Watson SJ. Connections of some auditory-responsive posterior thalamic nuclei putatively involved in activation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in response to audiogenic stress in rats: an anterograde and retrograde tract tracing study combined with Fos expression. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:474–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccatelli S, Cintra A, Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Wikstrom AC, Gustafsson JA. Coexistence of glucorticoid receptor-like immunoreactivity with neuropeptides in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 1989;78:33–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00230684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DC, Evanson NK, Furay AR, Ulrich-Lai YM, Ostrander MM, Herman JP. The anteroventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially regulates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis responses to acute and chronic stress. Endocrinol. 2008;149:818–826. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DC, Furay AR, Evanson NK, Ostrander MM, Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis subregions differentially regulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: implications for the integration of limbic inputs. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2025–2034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4301-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen DM, Elklit A. Risk factors predict post-traumatic stress disorder differently in men and women. Annals Gen Psychiatry. 2008;7:24–36. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad CD, Jackson JL, Wieczorek L, Baran SE, Harman JS, Wright RL, Korol DL. Acute stress impairs spatial memory in male but not female rats: influence of estrous cycle. Pharm, Biochem, Behav. 2004;78:569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Watson SJ. Ventral subicular interaction with the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: evidence for a relay in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332:1–20. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Masini CV, Campeau S. The pattern of brain c-fos mRNA induced by a component of fox odor, 2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline (TMT), in rats, suggests both systemic and processive stress characteristics. Brain Res. 2004;1025:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Nebel S, Sasse S, Campeau S. Inhibition of the central extended amygdala by loud noise and restraint stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:441–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Xu Y, Buller KM, Day TA. Effects of chronic oestrogen replacement on stress-induced activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis control pathways. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:784–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditlevsen DN, Elklit A. The combined effect of gender and age on post traumatic stress disorder: do men and women show differences in the lifespan distribution of the disorder? Annals Gen Psychiatry. 2010;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Petrovich GD, Watts AG, Swanson LW. Basic organization of projections from the oval and fusiform nuclei of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in adult rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:430–455. doi: 10.1002/cne.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossopoulou G, Antoniou K, Kitraki E, Papathanasiou G, Papalexi E, Dalla C, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z. Sex differences in behavioral, neurochemical and neuroendocrine effects induced by the forced swim test in rats. Neuroscience. 2004;126:849–857. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert MH, Herman JP. Differential forebrain c-fos mRNA induction by ether inhalation and novelty: evidence for distinctive stress pathways. Brain Res. 1999;845:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo HF, Dolgas CM, Herman JP. Stress activation of cortex and hippocampus is modulated by sex and stage of estrus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2534–2540. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo HF, Ulrich-Lai YM, Choi DC, Herman JP. Estrogen potentiates adrenocortical responses to stress in female rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1173–E1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00102.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forray MI, Gysling K. Role of noradrenergic projections to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;47:145–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabashi T, Kawaguchi M, Furuta M, Fukushima A, Kimura F. Exposure to bisphenol A during gestation and lactation causes loss of sex difference in corticotropin-releasing hormone-immunoreactive neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:475–485. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grino M, Héry M, Paulmyer-Lacroix O, Anglade G. Estrogens decrease expression of the corticotropin-releasing factor gene in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and of the proopiomelanocortin gene in the anterior pituitary of ovariectomized rats. Endocrine. 1995;3:395–398. doi: 10.1007/BF02935643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo AL, Petraglia F, Criscuolo M, Ficarra G, Nappi RE, Palumbo M, Valentini A, Genazzani AR. Acute stress- or lipopolysaccharide-induced corticosterone secretion in female rats is independent of the oestrous cycle. Eur J Endocrinol. 1994;131:535–539. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1310535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Burgess LH, Kerr JE, O’Keefe JA. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav. 1994;28:464–476. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinsbroek RP, van Haaren F, Feenstra MG, Endert E, van de Poll NE. Sex- and time-dependent changes in neurochemical and hormonal variables induced by predictable and unpredictable footshock. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:1251–1256. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90359-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, Cullinan WE. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Stein MB, Sieber WJ. Gender differences in long-term posttraumatic stress disorder outcomes after major trauma: women are at higher risk of adverse outcomes than men. J Trauma. 2002;53:882–888. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki-Sekino A, Mano-Otagiri A, Ohata H, Yamauchi N, Shibasaki T. Gender differences in corticotropin and corticosterone secretion and corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and the central nucleus of the amygdala in response to footshock stress or psychological stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2009;34:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju G, Swanson LW, Simerly RB. Studies on the cellular architecture of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in the rat: II. Chemoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:603–621. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERalpha and ERbeta) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:357–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980905)36:3<357::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfumey L, Mongeau R, Cohen-Salmon C, Hamon M. Corticosteroid-serotonin interactions in the neurobiological mechanisms of stress-related disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin JW, Binks SL, Li Y, Selvage D. The role of oestradiol in sexually dimorphic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrena axis responses to intracerebroventricular ethanol administration in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Mevel JC, Abitbol S, Beraud G, Maniey J. Dynamic changes in plasma adrenocorticotrophin after neurotropic stress in male and female rats. J Endocrinol. 1978;76:359–360. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0760359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linzer M, Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Hahn S, Brody D, deGruy F. Gender, quality of life, and mental disorders in primary care: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. Am J Med. 1996;101:526–533. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liposits Z, Uht RM, Harrison RW, Gibbs FP, Paull WK, Bohn MC. Ultrastructural localization of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in hypothalamic paraventricular neurons synthesizing corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) Histochem. 1987;87:407–412. doi: 10.1007/BF00496811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livezey GT, Miller JM, Vogel WH. Plasma norepinephrine, epinephrine and corticosterone stress responses to restraint in individual male and female rats, and their correlations. Neurosci Lett. 1985;62:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd RB, Nemeroff CB. The role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the pathophysiology of depression: therapeutic implications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:609–617. doi: 10.2174/1568026611109060609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunga P, Herbert J. 17Beta-oestradiol modulates glucocorticoid, neural and behavioural adaptations to repeated restraint stress in female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:776–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Furey BF, Child M, Sawyer MJ, Donohue SM. Neonatal sex hormones have ‘organizational effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of male rats. Dev Brain Res. 1998;105:295–307. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Linkroum W, Sallinen BJ, Miller NW. Peripheral and central sex steroids have differential effects on the HPA axis of male and female rats. Stress. 2002;5:235–247. doi: 10.1080/1025389021000061165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Wilson MA. A sexually dimorphic population of CRF neurons in the medial preoptic area. Neuroreport. 1994;5:653–656. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199401000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie KM, Rivier C. Gender difference in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to alcohol in the rat: activational role of gonadal steroids. Brain Res. 1997;766:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BP. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund H, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor gene expression in relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Annals NY Acad Sci. 2003;1007:54–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 5. Burlington, MA, USA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Phelix CF, Liposits Z, Paull WK. Serotonin-CRF interaction in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: a light microscopic double-label immunocytochemical analysis. Brain Res Bull. 1992;28:943–948. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90217-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelix CF, Liposits Z, Paull WK. Catecholamine-CRF synaptic interaction in a septal bed nucleus: afferents of neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:109–119. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley JJ, Gosselink KL, Sawchenko PE. A discrete GABAergic relay mediates medial prefrontal cortical inhibition of the neuroendocrine stress response. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7330–7340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley JJ, Sawchenko PE. A common substrate for prefrontal and hippocampal inhibition of the neuroendocrine stress response. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9683–9695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6040-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ME, Balestreire EM, Czambel RK, Rubin RT. Estrous cycle influences on sexual diergism of HPA axis responses to cholinergic stimulation in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2002;59:217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00868-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ME, Kennell JS, Belz EE, Czambel RK, Rubin RT. Rat estrous cycle influences the sexual diergism of HPA axis stimulation by nicotine. Brain Res Bull. 2004;64:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C. Gender, sex steroids, corticotropin-releasing factor, nitric oxide, and the HPA response to stress. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:739–751. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy BN, Reid RL, van Vugt DA. The effects of estrogen and progesterone on corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the paraventricular nucleus and supraoptic nucleus of the rhesus monkey. Endocrinol. 1999;140:2191–2198. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.5.6684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale JV, Wood SA, Atkinson HC, Bate E, Lightman SL, Ingram CD, Jessop DS, Harbuz MS. Gonadectomy reverses the sexually diergic patterns of circadian and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in male and female rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, Chang C, Muramatsu M, Swanson LW. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Therapy. 2000;38:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterrenburg L, Gaszner B, Boerrigter J, Santbergen L, Bramini M, Roubos EW, Peeters BW, Kozicz T. Sex-dependent and differential responses to acute restraint stress of corticotropin-releasing factor-producing neurons in the rat paraventricular nucleus, central amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:179–192. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström JO, Theodorsson E, Theodorsson A. Order of magnitude differences between methods for maintaining physiological 17beta-oestradiol concentrations in ovariectomized rats. Scan J Clin Lab Investig. 2008;68:814–822. doi: 10.1080/00365510802409703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Hanna IK. Ontogeny of sex differences in the mammalian hypothalamus and preoptic area. Cell Molec Neurobiol. 1997;17:565–601. doi: 10.1023/A:1022529918810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis D. Region- and sex-specific modulation of anxiety behaviours in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:461–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakopoulos NC, Chrousos GP. Evidence of direct estrogenic regulation of human corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression. Potential implications for the sexual dimophism of the stress response and immune/inflammatory reaction. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1896–1902. doi: 10.1172/JCI116782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Velde S, Bracke P, Levecque K. Gender differences in depression in 23 European countries. Cross-national variation in the gender gap in depression. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesga-López O, Schneier FR, Wang S, Heimberg RG, Liu S, Hasin DS, Blanco C. Gender differences in generalized anxiety disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1606–1616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V. Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:506–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Bingham B, Davis J, Lee P, Wong M. Gender and puberty interact on the stress-induced activation of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons and corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the rat. Endocrinol. 2005;146:137–146. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Meaney MJ. Variations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress during the estrous cycle in the rat. Endocrinol. 1991;129:2503–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Meaney MJ. The inhibitory effect of testosterone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress is mediated by the medial preoptic area. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1866–1876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01866.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Meaney MJ. Alpha1 adrenoreceptors mediate the stimulatory effects of oestrogen on stress-related hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in the female rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Miles LA, Davis M. Selective participation of the bed nucelus of the stria terminalis and CRF in sustained anxiety-like versus phasic fear-like responses. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1291–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M, Razin M, Schorer-Apelbaum D, Men D, McCarty R. Gender differences in sympathoadrenal activity in rats at rest and in response to footshock stress. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1998;16:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M, Bingham B, Gray M, Innala L, Viau V. The medial preoptic nucleus integrates the central influences of testosterone on the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and its extended circuitries. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11762–11770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2852-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M, Viau V. Androgen receptor expressing neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the male rat. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:717–740. doi: 10.1002/cne.21411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Altemus M, Parkison V, Shastry S. Effects of estrogen antagonists and agonists on the ACTH response to restraint stress in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;25:881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]