Abstract

Helix 69 of E. coli 23S rRNA has important roles in specific steps of translation, such as subunit association, translocation, and ribosome recycling. An M13 phage library was used to identify peptide ligands with affinity for helix 69. One selected sequence, NQVANHQ, was shown through a bead assay to interact with helix 69. Electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy revealed an apparent dissociation constant for the amidated peptide and helix 69 in the low micromolar range. This value is comparable to that of aminoglycoside antibiotics binding to the A site of 16S rRNA or helix 69. Helix 69 variants (human) and unrelated RNAs (helix 31 or A site of 16S rRNA) showed two- to four-fold lower affinity for NQVANHQ-NH2. These results suggest that the peptide has desirable features for development as a lead compound for novel antimicrobials.

Keywords: RNA, modified nucleotides, pseudouridine, antibiotics, phage display

1. Introduction

In the 1960s, newly discovered antibiotics were thought to be the perfect solution to bacterial infections; however, most successful antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, have been compromised due to the emergence of bacterial resistance.1 Bacteria have acquired resistance through a number of pathways, including target modification.2 As a consequence, antibiotic discovery has again gained momentum in the search for new compounds and targets. To design novel antibiotics against which pathogens have not yet acquired resistance, new bacterial target sites with known structures and functions are being explored. Furthermore, focusing on highly conserved regions of pathogen genomes is important for the discovery of broad-spectrum drugs. Detailed knowledge of the bacterial ribosome structure obtained through crystallography and cryoEM studies has provided insight into functionally important, conserved regions of the ribosomal RNA (rRNA).3 The ribosome is still considered an important target for drug discovery because of its essential function and diverse tertiary structure.4 One notable region is the highly modified helix 69 (H69), which is present in the heart of the ribosomal machinery.5 Helix 69 (Fig. 1) is located in domain IV (residues 1906–1924, E. coli numbering) of 23S rRNA and forms a bridge known as B2a with helix 44 of 16S rRNA at the ribosomal subunit interface.3a Helix 69 has a role in a number of different ribosome processes, such as subunit association,6 translational fidelity,7 and ribosome recycling,3c, 3e, 8 due to its presence in the interface region. This multitasking function of H69 is likely related to its ability to undergo dynamic rearrangements.3b, 3e, 8–9

Figure 1.

The secondary structures of wild-type E. coli (Ψm3ΨΨ) and human H69 (Ψ5) show sequence differences (Ψ, pseudouridine; m3Ψ, 3-methylpseudouridine). Nucleotides in upper case letters in the E. coli H69 sequence have >95% conservation and those in lower case have 88-95% conservation across phylogeny.10 The UUU RNA has Us in place of Ψs. The H69 variants referred to as UΨΨ, ΨUΨ, and ΨΨU have Ψ to U substitutions at positions 1911, 1915, and 1917, respectively.

Although H69 is highly conserved in terms of sequence and pseudouridine (Ψ) modifications, comparisons between bacteria (E. coli) and eukaryotes (H. sapiens) reveal some notable differences (Fig. 1).10–11 The first is that one of the three conserved pseudouridines, Ψ1915, is methylated in E. coli, but not in human, rRNA.12 Second, the 3′-loop-closing nucleotide is an A in bacteria and a G in higher organisms.10, 13 Third, the H. sapiens H69 has two additional Ψs in the stem region, including an A-Ψ pair and a G•Ψ mismatch.14 These changes in sequence and modification lead to differences in the solution conformations of the bacterial and human H69 RNAs.11

Sequence and structural differences between bacterial and human H69 combined with functional significance make H69 an ideal antibacterial target. Indeed, recent reports indicated that H69 is a target site for aminoglycoside antibiotics15 and thermorubin.15c Most naturally derived compounds have already given rise to resistance or will lead to resistance before long.1 The goal for this work was to discover new compounds, starting with small peptides that specifically bind to H69. Phage display16 was used previously to isolate peptides that bind to a wide range of targets, including tRNA and rRNA.17 In this study, peptide ligands against H69 were identified after four rounds of selection. Further studies with chemically synthesized, amidated peptides corresponding to these sequences involved determination of apparent dissociation constants (Kd values) with H69 RNA by using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS).18 One peptide, NQVANHQ-NH2, displayed preferential binding for modified H69 over unmodified, variant, and human H69s, as well as unrelated RNAs, with moderate affinity (Kd of low μM) and pH dependence.

2. Materials and Methods

2 .1. Materials

A Ph.D.-7TM phage display library kit was purchased from New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswich, MA), which included the sequencing primers (-96 g3, 5′-CCCTCATAGTTAGCGTAA CG-3′, and -28 g3, 5′-GTATGGGATTTGCTAAACAAC-3′). Streptavidin-coated 96-well plates (Reacti-BindTM), used for immobilizing biotinylated RNA, were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The solutions used for biopanning included LB medium, TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl), PEG/NaCl (20% w/v polyethylene glycol-8000, 2.5 M NaCl), TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20), buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT), buffer B (0.2 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.2, 1 mg/mL BSA), TBS with 0.02% sodium azide (final concentration), and equilibrated phenol (pH >8). Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal), tetracycline, BSA, phenol, and Tween-20 were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The 0.2 M IPTG/0.1 M X-gal and 0.045 M tetracycline stock solutions were prepared in ethanol and stored in the dark at −20 °C. A Sequitherm EXCEL II DNA sequencing kit was obtained from Epicentre Biotech (Madison, WI).

2.2. Instrumentation

For the TentaGel™ bead assay, an ApoTome Axioplan Imaging 2 microscope or Zeiss fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss International, Tübigen, Germany) was used. All ESI-MS experiments were conducted on a Quattro LC tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization (ESI) inlet (Micromass, Manchester, UK).

2.3. RNA preparation

Helix 69 (H69) RNA (5′-GGCCGΨAACm3ΨAΨAACG GUC-3′) was custom synthesized at Dharmacon Research, Inc. (Lafayette, CO). The 3-methylpseudouridine (m3Ψ) phosphoramidite was synthesized in our laboratory.19 H69 was biotinylated at the 5′ end using an oligonucleotide biotin-labeling kit from Amersham GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). Unmodified H69, variant H69 constructs, and unrelated RNAs (helix 31, bacterial A-site RNA, human A-site RNA (F-18S), TAR RNA, and F-TAR RNA) were obtained from Dharmacon Research, Inc. Modified H69 with a 5′-amino-6-carbon linker (5′-NH2-C6-GGCCGΨAACm3ΨAΨAACGGUC-3′) was labeled with fluorescein. The reaction was carried out with 0.0125 μmoles of RNA, diisopropylethylamine (7%), DMSO (35%), and 0.75 μmoles of fluorescein isothiocyanate for 22 h in the dark with agitation. All RNAs were purified on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels (7 M urea). The appropriate RNA bands were visualized by UV shadowing, excised, and subjected to electroelution and desalting. The RNAs were stored in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4. The final RNA concentration was calculated using the extinction coefficients of 187,000 M−1cm−1 for H69 RNAs, 176,900 M−1cm−1 for helix 31, 242,400 M−1cm−1 for the bacterial A-site RNA, 258,100 M−1cm−1 for human A-site RNA (F-18S), and 268,900 M−1cm−1 for TAR RNA and F-TAR RNA. The RNAs were renatured before use.

2.4. Phage display

For the biopanning steps, or affinity selection, the process was carried out according to the protocol provided by NEB (Ph.D-7.TM kit) with only minor modifications. During the first level of stringency (round 1), biotinylated H69 RNA (B-H69, 50 pmoles) was incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking in one well of the streptavidin-coated microtiter plate, in 150 μL buffer A. The binding solution was then poured off and the well was blocked with 3 mg/mL BSA for 1.5 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, the well was washed 6× with 300 μL TBST. The phage solution (10 μL of the original library in 100 μL buffer A, 2 x 1011 pfu, in which pfu is plaque forming unit) was pipetted into a well having no immobilized target RNA and incubated for 1 h at RT with gentle shaking for prescreening of the library. The phage library was then removed, added to the well containing the immobilized target RNA, and incubated for 1 h at RT, with gentle shaking. After 1 h, the library was removed and the unbound phage were washed with 300 μL TBST (12×). The bound phage in rounds 1–3 were eluted with 100 μL 0.2 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.2) containing 1 mg/mL BSA and neutralized immediately with 15 μL 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. The eluate was titered and amplified in ER2738 cells for use in subsequent rounds of panning.

In the next level of stringency (round 2), the phage were incubated with 20 pmoles of B-H69 RNA, the well was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (300 μL, 1 h at 4 °C), and then washed with 300 μL TBST with 0.3% Tween-20. The amplified phage from round 1 were incubated for 30 min at RT with the B-H69 RNA. To remove unbound phage, the timing was 30 sec for even washes and 3 min for odd washes, and 12 (300 μL each) washes with TBST (containing 0.3% Tween-20) were carried out. In the third round, the amount of B-H69 RNA was reduced to 10 pmoles, and blocking of the well containing immobilized RNA was done with 3% BSA. The amplified phage library from round 2 was incubated with target RNA for 15 min at RT with gentle shaking. To remove unbound phage, 14 alternating washes (30 sec and 3 min) were carried out. For round 4, 10 pmoles of B-H69 RNA were immobilized in each of two separate wells on the streptavidin-coated plate in order to carry out specific and non-specific elution of the bound phage. Specific elution was carried out with 30 pmoles of H69 RNA in TBST buffer, and non-specific elution was performed as described above. The other experimental conditions were kept the same as round 3. The conditions for selection are summarized in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). Licor sequencing for rounds 3 and 4 was carried out by using the primer -96 g3 with IR-700 dye at its 5′ end and isolated DNAs from individual plaques as described in the NEB protocol.

2.5. Peptide synthesis

After their sequences were identified, the selected peptides were chemically synthesized using micro TentaGel™ S-NH2 beads (Rapp Polymere GmbH, Germany) by standard Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) procedures.20 The peptide beads were washed thoroughly with DMF and stored in DMF at 4 °C before use. In addition, the free peptides with C-terminal amidation were synthesized by following standard Fmoc-based SPPS on Rink amide AM resin (Novabiochem, Germany). The peptide synthesis was started with addition of resin (mmol) into a peptide-synthesis reaction vessel mounted on a wrist-action shaker. After swelling of the resin, the procedure involved sequential coupling of residues. The Kaiser test was performed to confirm complete coupling. The free peptides were cleaved by adding resin cleavage solution (trifluoroacetic acid, anisole, thioanisole, and triisopropyl silane, 94:2:2:2 ratio) with shaking for 2 h. The solution was separated equally in two 10 mL test tubes, followed by addition of ethyl ether (−20 °C) to reach 20% of total tube capacity. After mixing the solution, the peptide precipitated. The supernatant was removed and the pelleted peptide was thoroughly washed with ether three more times. Finally, the peptide was dissolved in distilled water (5–10 mL), frozen, and lyophilized for 24-48 h until a white powder was obtained. Peptides were characterized by using MALDI mass spectrometry.

2.6. Bead analysis

TentaGel™ beads containing the selected peptide sequences STYTSVS and NQVANHQ were washed with water to remove residual DMF. The beads were then blocked with 500 μL Pierce SuperBlock buffer (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20, Pierce Inc., Rockford, IL) for 3 h, followed by a wash with ddH2O (500 μL, 3×). As a control for background fluorescence, beads without peptide were blocked and washed. To determine RNase activity in the buffer, the RNAs were incubated in each buffer for 16 h and then run on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. No degradation of RNA was observed. A small quantity of the beads (~10–12) was extracted from the solution and 15 μL of 1 μM F-H69 RNA in 10 mM HEPES buffer was added to the beads. The suspension was then agitated on a shaker for 24 h at 4 °C. The RNA was removed and a fresh solution of F-H69 was added to the beads, which were incubated another 24 h. This process was repeated 4× to achieve maximum fluorescence. The beads were washed with ddH2O (500 μL, 3×) and then visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

A second bead assay with quantum dots (Qdots) was carried out. The peptide beads were pre-blocked in buffer A (SuperBlock Buffer, pH 7.2, with 0.05% Tween-20, 0.10 M NaCl, and 0.5 mg/mL fish gelatin) for 4 h at 4 °C in a Nanosep centrifugal device (300K cutoff) from VWR (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI). Fluorescein-labeled RNA (1 nM) and anti-fluorescein Qdot® 655 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) (1 nM) were pre-incubated for 1 h at 4 °C in buffer A. The peptide beads were then incubated with Qdot-labeled RNA for 16 h at 4 °C in the Nanosep columns. The beads were washed 4× with 1× PBS (400 μL), twice with SuperBlock blocking buffer, and once with SuperBlock buffer containing 0.005% TX-100. The beads were evaluated for binding under a fluorescence microscope. The red fluorescence intensity values from each bead arising from Qdot 655 and green fluorescence values from each bead arising from fluorescein were evaluated using Adobe Photoshop software. The relative pixel intensity scale ranges from 1–255. With predefined exposure times, the pixel intensity values correlate to the amount of on-bead binding of labeled RNA. Qdot 655 (excitation ~360 nm (broad excitation); emission 655 nm; Quantum Dot Corp) was used because its far-red narrow emission is very stable and has less background.

2.7. ESI-MS

The binding of free peptides to RNA was evaluated by using ESI-MS as described previously.17b The optimized conditions for these studies employed 50 μL of 1–3 μM RNA, 150 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.2 or pH 7.0, 25% 2-propanol, and 0–120 μM peptide. The mixtures of RNA and peptide were equilibrated for 30 min at RT before each measurement. In the spectra of the free RNA, the 4−and 5−charge states were observed; whereas, in the spectra of the RNA-peptide complexes, the 4−charge state was the dominant species. The formation of 1:1 complex between RNA and peptide NQVANHQ-NH2 was greater than the 1:2 complex. Mass LynxTM 4.0 was used for data collection and analysis. For calculation of the peak areas, the spectra were smoothed once from the full-width at half-height value using the Savitzky-Golay method before integration (command for integration in the Mass LynxTM 4.0). In performing these experiments, it was assumed that the summed peak areas of the charge states of the free RNA, 1:1, and 1:2 complexes was comparative to the concentrations of the free RNA, 1:1, and 1:2 complexes in solution, respectively. This assumption was considered reasonable, since low concentrations of RNA and peptide were employed.

For calculating apparent Kd values, the sum of the peak areas of all observed charge states is generally taken into account.21 Therefore, the peak intensities of free RNA ions, RNA-Na+ and RNA-K+ adduct ions in the 4−and 5−charge states were summed. Similarly, the peak intensities of the RNA-peptide complexes (including 1:1, 1:2) and their Na+ and K+ ion adducts were summed. The fraction of RNA bound was calculated by dividing the peak intensity of RNA-peptide complexes with summation of peak intensities of free RNA and RNA-peptide complexes. The apparent Kd was calculated by plotting the fraction of RNA bound versus the concentration of peptide using non-linear curve fitting with a quadratic equation (Eq. 1).

| (1) |

In equation 1, [R]o is the total concentration of RNA, [P]o is the total concentration of peptide, ΣRPn−is the total concentration of RNA-peptide complexes at a given charge state or all charge states, ΣRn− is the total concentration of free RNA at a given charge state or all charge states (depending upon which approach is used). KaleidaGraph software was employed to fit the data, and apparent Kd values were calculated with Eq. 1. In another approach, the apparent Kd for the 1:1 complex was calculated for the individual charge states of 4−and 5−, in which the peak areas of free RNA H69 and complexed RNA with salt adducts at the individual charge state were summed. The fraction of H69 bound to the peptide at a particular charge state was calculated by dividing peak intensity of the H69-peptide complexes with the summation of the peak intensities of the free RNA and the RNA-peptide complexes. The data were analyzed using Eq. 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection of heptapeptides with affinity for H69

A commercial phage display library was employed, and four rounds of selection against wild-type, fully modified, bacterial H69 (referred to as Ψm3ΨΨ) as the target were carried out as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The phage display process, as applied to selection of peptides for H69 RNA (Ψm3ΨΨ), is summarized. Four rounds were performed with increasing stringencies. B-H69 corresponds to 5′-biotinylated H69.

The library was composed of random, linear heptapeptides (five copies of each) fused to the surface-exposed minor coat protein (pIII) of M13 phage.22 To reduce non-specific interactions and obtain peptides with preferred binding to H69, the stringency of each round was increased, and competitor tRNA was employed (Table S1). The first step of each round involved fresh immobilization of 5′-biotinylated H69 (B-H69) onto streptavidin-coated plates. The amount of target B-H69 was decreased with each round (from 50 to 10 pmoles), with the intention of increasing the population of peptides with higher affinity for H69.23 Blocking buffers were included in each round. In addition, the binding times of the phage library were reduced in each successive round, from 60 to 15 minutes, in order to favor peptides with faster kinetic on rates (kon). The unbound phage population was removed with washing buffer having increasing levels of detergent, Tween-20 (0.1 to 0.5%). In order to obtain peptides with slower off rates (koff), the wash times and numbers were also varied.24 One additional variable was the elution condition, in which removal of the bound phage was performed in either a non-specific or specific manner. The non-specific elution was carried under low pH conditions, and specific elution was carried out with three-times higher concentrations of target H69 RNA at pH 7.5.

After three rounds of selection with non-specific elution, peptides with the consensus sequence TSVS appeared. Peptide sequences not related to that consensus were also obtained (Table S2, Supplementary Material). After the fourth round, non-specific and specific elutions were carried out in parallel. Under non-specific elution conditions, the peptide STYTSVS with consensus TSVS dominated the pool; whereas, specific elution favored two peptides, STYTSVS and NQVANHQ (Table S3, Supplementary Material). Selection was also performed against streptavidin with no immobilized target RNA as a control. In this case, the well-known consensus HPQ/L for streptavidin ligands was obtained (Table S2).

3.2. On-bead analysis of heptapeptide binding to H69

Two peptide sequences, NQVANHQ and STYTSVS, were selected for H69 binding studies. A simple fluorescence-based assay using TentaGel™ beads was developed to establish the relative binding affinities of these peptides for H69. This assay was a modified version of an on-bead combinatorial assay developed by Lam and Lebl.25 The conditions of our modified assay, such as the type of blocking buffer and incubation time of the beads and RNA, were optimized by using two tripeptides, KL-KD-NL and RL-KD-VD, which were obtained in an on-bead selection by Hwang and coworkers,26 and 5′-fluorescein-tagged TAR RNA (F-TAR) (Fig. S1, Supplementary Material) as the model system. The tripeptides were synthesized on TentaGel™ beads, and binding to RNA was carried using a modified literature procedure.17b The peptides were displayed on the beads with a free amino terminus, which is the same orientation as the peptides on phage. The optimized assay conditions were then used to approximate the relative binding affinities of the heptapeptides against 5′-fluorescein-tagged H69 (F-H69). The intensities of the fluorescing beads were used to give a preliminary understanding of the relative binding affinities of the selected peptides for the target H69 and unrelated RNA sequences.

The fluorescence intensity of beads bearing NQVANHQ and incubated with F-H69 was higher than beads with the STYTSVS peptide, indicating that the former has stronger affinity for H69 (Fig. 3A). Control experiments were carried out with free fluorescein and several unrelated, 5′-fluorescein-tagged RNAs, including F-TAR RNA and F-18S RNA (the human decoding region, or A-site, rRNA, shown in Fig. S1). There was no detectable interaction between free fluorescein and the peptide beads (Fig. 3B). Similarly, the NQVANHQ peptide beads did not show any interaction with F-TAR RNA or F-18S RNAs, suggesting specific binding of this peptide to H69. In contrast, the STYSTVS peptide beads showed interaction with one of the unrelated RNAs, F-TAR (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

A) Direct fluorescence images show NQVANHQ- and STYTSVS-containing TentaGel beads incubated with F-H69 (5′-fluorescein-tagged Ψm3ΨΨ). B) The peptide beads when incubated with controls, fluorescein, F-18S RNA (human A-site rRNA), and F-TAR RNA (upper: NQVANHQ; lower: STYTSVS), do not show any fluorescence, with the exception those containing STYTSVS and F-TAR RNA.

The fluorescence assay was repeated with quantum dots (Qdots) attached to an anti-fluorescein antibody.27 The Qdots display brighter fluorescence with prolonged photostability compared to fluorescein.28 The Qdots were incubated with the mixture of peptide beads and F-H69 RNA at concentrations as low as 1 nM. The images of the beads were monitored under a fluorescence microscope using the merged emission of fluorescein (F-H69) and anti-fluorescein Qdot 655. The yellow color of the NQVANHQ beads, along with quantification of both fluorescein and Qdot 655 fluorescence, revealed this peptide to have a two-fold higher affinity for H69 than STYTSVS (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A) TentaGel bead images for both peptides (left: STYTSVS; right: NQVANHQ) are shown with merged emission from fluorescein (labeled Ψm3ΨΨ; F-H69; excitation 494 nm; emission 521 nm) and the anti-fluorescein Qdot 655 (bound to F-H69; excitation 360 nm; emission 655 nm). B) Fluorescence intensities of the two peptides are shown with the control (no peptide).

By comparison, the fluorescein-based bead assay is not very convenient due to the long incubation times and high number of washing steps required, although this assay was useful for evaluating the preliminary binding affinity and specificity of the peptides selected for H69. The Qdot assay proved to be more convenient and quantitative; however, having the peptide attached to a bead could influence binding to H69 RNA. Therefore, binding of the free peptide to H69 needed to be validated.

3.3 ESI-MS analysis of NQVANHQ-NH2 binding to H69 RNAs

ESI-MS was used to determine the affinity of free peptide for H69. In such studies, only nanogram amounts of sample are required, no labeling of the participating molecules is necessary, and the stoichiometry of the complexes can be obtained.18 ESI-MS has been applied successfully for characterizing non-covalent complexes of nucleic acids and proteins, and the apparent Kd values obtained with ESI-MS correlate well with those determined from other solution measurements.29

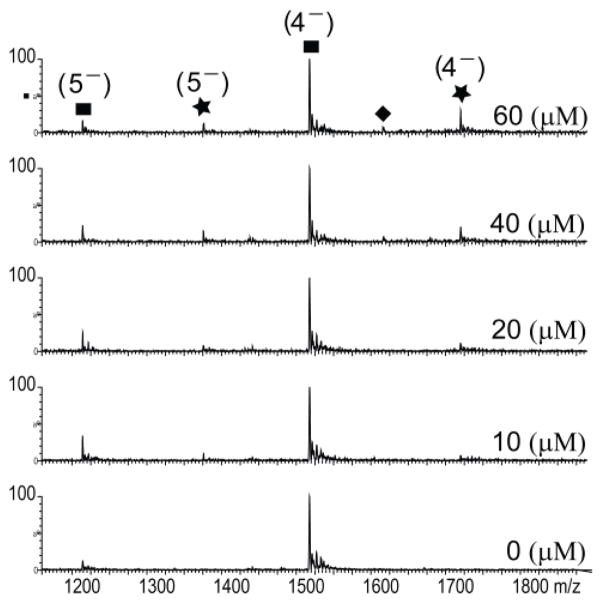

Binding experiments were carried out with Ψm3ΨΨ H69 RNA and a range of concentrations (0–120 μM) of amidated peptide, NQVANHQ-NH2, in 150 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.0. A 1:1 complex of RNA and peptide was observed in the 4–and 5−charge states, with the dominant species in the 4−charge state. The ESI spectra for H69 RNA and peptide from 0 to 60 μM are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The ESI spectra show free Ψm3ΨΨ RNA (4−and 5−charge states; ●) and the 1:1 H69-NQVANHQ-NH2 complex (4−and 5−charge states;★) with increasing peptide concentration (0 to 60 μM) in 150 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.0, and 25% isopropanol. Peptide dimer (◆) is observed at higher ligand concentrations.

In one approach, the fraction of RNA bound to peptide was calculated based on the sum of the total complexes, in which ΣRPn− is the total intensity of RNA-peptide complexes and their salt adducts at all stoichiometries (1:1, 1:1 + 1:2, etc.), and the data were analyzed using a quadratic equation (Eq. 1, Materials and Methods). The apparent Kd for the H69-peptide complex based on the sum of all charge states is 21 ± 3 μM (Fig. 6A). The fraction of RNA bound in a 1:1 complex was also estimated based on the individual charge states. The apparent Kd for the 1:1 complex is 12 ± 1 μM for the dominant 4−charge state and 16 ± 6 μM for the less abundant 5−charge state (Fig. 6B). The error bars shown on each point in the titration plots were based on the standard deviations from three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

A) The apparent Kd was determined from the fraction of Ψm3ΨΨ bound to NQVANHQ-NH2 peptide, including all charge states (4 and 5 ) and complexes (1:1 and 1:2). B) The apparent Kd is determined from the fraction of H69 bound to peptide for the 4−charge state and 1:1 complex with NQVANHQ-NH2. The apparent Kd and corresponding error were obtained by using a quadratic equation. Each point is the average value from three independent titrations.

The accuracy of ESI-MS was challenged by the presence of a low fraction of the complex relative to free RNA, particularly for the 5−charge state. Furthermore, complete disappearance of the free species of RNA in favor of the RNA-peptide complex was not observed due to the low ionization efficiency of the RNA-peptide complex. Thus, relative values of Kd were obtained instead of the absolute values,30 and saturation was considered to be achieved when the fraction of bound RNA no longer changed. Despite these challenges, previous studies demonstrated that the ESI-MS method provides comparable Kd values for peptide-RNA complexes as other biophysical methods such as isothermal titration calorimetry and enzymatic footprinting .17b

The role of Ψ residues in H69 binding to the peptide was investigated by using ESI-MS. For this purpose, three H69 constructs having uridine (U) in place of pseudouridine (Ψ) at positions 1911, 1915, and 1917 (UΨΨ, ΨUΨ, and ΨΨU, respectively, Fig. 1) were employed. An unmodified RNA construct with all Ψs replaced with Us (UUU) was also examined in order to determine the collective effect of Ψs on peptide binding. The apparent Kd values for the 1:1 complexes of NQVANHQ-NH2 with these H69 constructs were determined at pH 7.0, and the results are summarized in Table 1. The apparent Kd for the dominant 4−charge state of the 1:1 complex of UUU-NQVANHQ-NH2 is 19 ± 2 μM. The 1.6-fold higher Kd for the unmodified RNA compared to modified H69 reveals a slight influence of the Ψ residues on peptide binding. Previous studies showed that the UUU and Ψm3ΨΨ RNAs have different loop structures, which could impact peptide binding.11, 19, 31

Table 1.

Apparent dissociation constants for 1:1 complexes of H69 and unrelated RNAs with NQVANHQ-NH2.

| E. coli H69 and variants | Kd at pH 7.0 (μM) | human H69 and unrelated RNAs | Kd at pH 7.0 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ψm3ΨΨ (wt) | 12 ± 1 | ||

| UUU | 19 ± 2 | Ψ5 | 50 ± 8 |

| UΨΨ | 28 ± 5 | h31 | 33 ± 10 |

| ΨUΨ | 28 ± 4 | A site | 49 ± 10 |

| ΨΨU | 28 ± 4 |

The apparent Kd values for the 1:1 complexes of UΨΨ, ΨUΨ and ΨΨU with NQVANHQ-NH2 (4−charge state) were all 28 μM (Table 1). The 2.3-fold higher dissociation constants for the partially modified constructs compared to that of Ψm3ΨΨ indicate roles for the individual Ψ residues in peptide binding that differ from those in the fully modified RNA. These results suggest that peptide binding could be located at or near the H69 loop region. The slightly reduced affinity of the peptide towards these constructs is supported by the fact that individual Ψ residues have subtle, but different, effects on H69 structure and stability than the combination of three Ψs.31 The methyl group at position 1915 does not appear to influence the Kd value, since a modified RNA with three pseudouridines (ΨΨΨ) gives similar results as Ψm3ΨΨ (data not shown).

3.4. pH dependence of NQVANHQ-NH2 binding to Ψm3ΨΨ and UUU H69

The next set of studies determined the effects of pH on NQVANHQ-NH2 binding to H69. Earlier reports revealed pH-dependent conformational switching of H69, both in model studies and in 50S ribosomes.9a, 32 Circular dichroism and NMR spectroscopy, as well as chemical probing results, indicated a conformational state of H69 at pH 7.0 with greater solvent exposure of residue A1913 and decreased stacking of loop nucleotides in comparison to the structure at pH 5.5. ESI-MS titrations of NQVANHQ-NH2 with Ψm3ΨΨ and UUU H69 RNAs were carried out at pH 5.2. The apparent Kd for the 1:1 Ψm3ΨΨ-NQVANHQ-NH2 complex at the 4−charge state is 34 ± 3 μM (Table 2), 2.8-fold higher than the Kd at pH 7.0.

Table 2.

Apparent dissociation constants for 1:1 complexes of wild-type H69 (Ψm3ΨΨ) and UUU RNAs with NQVANHQ-NH2.

| RNA | Kd at pH 7.0 (μM) | Kd at pH 5.2 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Ψm3ΨΨ (wt) | 12 ± 1 | 34 ± 3 |

| UUU | 19 ± 2 | 31 ± 3 |

The binding of NQVANHQ-NH2 to UUU H69 was also compared at pH 7.0 and 5.2. The apparent Kd for the 1:1 complex in the 4−charge state at pH 5.2 is 31 ± 3 μM. This 1.6-fold higher value compared to that at pH 7.0 indicates a slight influence of pH on peptide interactions with UUU H69. The UUU RNA global conformation was previously shown by circular dichroism and NMR spectroscopy to be unaffected by the change in pH.32 Although the difference of the free energy values of UUU H69 at pH 7.0 and 5.2 is almost negligible, the binding affinity of the peptide for the RNA is reduced slightly (Table 2). This result suggests that a change at the peptide level from high to low pH might play a role in reduction of the binding affinity for H69 RNA.

The change in H69 conformational states between pH 7.0 and 5.5 could contribute to decreased peptide affinity. If that is the case, then the binding site of the peptide could be near the H69 loop region. An alternate explanation is that certain peptide functional groups get protonated at lower pH, which could inhibit interactions with H69. A comparison of free energy values (ΔG°37) for modified H69 at the two pH values (−5.3 kcal/mol at pH 5.5 and −4.7 kcal/mol at pH 7.0) indicates that the peptide has a slight preference for the thermodynamically less stable H69 conformer. The low and high pH conformational states of H69 are believed to mimic the structures observed in isolated 50S subunits and 70S ribosomes, respectively.32 Therefore, a preference in binding to 50S or 70S ribosomes would be significant with respect to mechanism-based targeting.

3.5. Selectivity of NQVANHQ-NH2 for H69

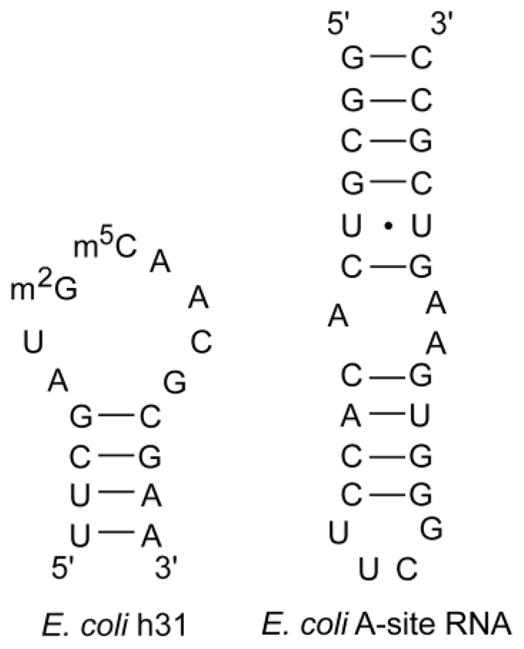

The selectivity in binding of peptide NQVANHQ-NH2 to fully modified H69 (Ψm3ΨΨ) compared to other RNAs was addressed by carrying out ESI-MS studies with three other rRNA constructs, human H69 (Fig. 1), helix 31 (h31), and the bacterial A-site RNA (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The sequences of the unrelated RNAs, E. coli A-site RNA and helix 31 (h31), that were used for ESI-MS experiments are shown.

Helix 31 of E. coli 16S rRNA is located near the P site and involved in translation.33 The A-site RNA is part of the bacterial decoding region and located in h44 of 16S rRNA. This RNA motif plays a crucial role in translation and binds to aminoglycoside antibiotics.34 The apparent Kd values obtained for the small subunit rRNAs (h31 and A site) at pH 7.0 in a 1:1 complex with peptide NQVANHQ-NH2 are three- and four-fold higher, respectively, than for bacterial H69 (Table 1). These results show that the peptide selected for H69 has reduced affinity for unrelated RNAs at physiological pH.

The human sequence of the H69 (referred to as Ψ5) has five Ψ residues compared to three in the E. coli H69.14 The Kd value for this RNA with peptide (50 ± 8 μM) is four-fold higher than value for E. coli H69 (Table 1). This result shows that the peptide also has a preference for bacterial H69 over the human H69. This feature of the peptide is important if it is to be considered as a potential lead for new antibacterials.

3.6 Comparison to ribosome-binding proteins and H69-binding ligands

The selected peptide NQVANHQ has a unique sequence for which no consensus appeared during the selection, but contains an abundance of amino acid residues that are also present in the ribosome recycling factor, RRF, a protein component of the ribosome known to make contacts with H69 (serine (S17), valine (V20), histidine (H23), and asparagine (N24) residues of RRF make contact with H69).3c Another peptide sequence having the consensus TSVS, STYTSVS, also appeared in the selection, but showed weak affinity and low selectivity for H69.

The apparent Kd value for H69 and NQVANHQ-NH2 is only a relative number due to the poor ionization efficiency of the complex in ESI-MS. In contrast, aminoglycoside-RNA complexes, in which electrostatic interactions are known to play a major role, have much higher ionization efficiencies.18, 35 The stoichiometry of the interaction of peptide for H69 is 1:1, revealing the interaction to be relatively specific. This result with NQVANHQ-NH2 is in contrast to binding studies with the well-known aminoglycoside neomycin and H69 RNA, in which comparable Kd values (low μM) are observed, but with higher stoichiometries and lower selectivity with human H69 due to non-specific binding interactions.15b Thus, the selected H69 peptide has several advantages over previously known ribosome-targeting compounds.

The ESI-MS experiments with the H69 variant UUU (Us in place of Ψs at positions 1911, 1915, and 1917) and peptide NQVANHQ-NH2 reveal an approximate two-fold difference in Kd for the 1:1 complex. This difference shows that the presence of the three Ψ residues contributes positively towards binding to the peptide. Furthermore, these results suggest that the peptide may distinguish modified and unmodified H69 in a similar fashion as the aminoglycoside paromomycin, in which a two-fold difference in affinity to the two H69 RNAs was observed.15b

4. Conclusions

A phage display methodology was employed to find peptides that bind to the biologically relevant ribosomal motif known as H69. One of the selected peptides, NQVANHQ-NH2, was found to bind H69 RNA with moderate affinity (low μM). For both direct fluorescence measurements and Qdot analysis, the intensity of the NQVANHQ beads was higher than STYTSVS beads, indicating a higher affinity of NQVANHQ to H69. There is sufficient evidence in the literature to demonstrate that ESI-MS is a reliable method for detecting non-covalent complexes of biological species, including RNA and small molecules.18, 36 ESI-MS revealed the stoichiometry and provided relative Kd values of the H69-peptide complexes. The use of this type of approach is supported by results of ESI-MS titrations with aminoglycosides and the A site of 16S rRNA, which have low μM affinities.36 The apparent Kd obtained with modified H69 and NQVANHQ-NH2 was also in the low micromolar range, suggesting the possible utility of the peptide for discovery of improved H69-targeting compounds.

To learn about the roles of individual Ψs at positions 1911, 1915 and 1917 in binding peptide, experiments were performed with H69 variants UΨΨ, ΨUΨ, and ΨΨU. The observed differences in affinity of these RNAs for peptide suggest that NQVANHQ-NH2 binding occurs at or near the H69 loop region. This result also suggests that small differences in H69 stability due to the presence or lack of single modifications31 may affect peptide binding.

The effects of pH on complex formation of H69 and NQVANHQ-NH2 were also studied, and the decreased affinity at low pH compared to pH 7.0 indicates that protonation of the RNA and/or peptide influences the binding event. Pending further experimentation, the exact protonation site and specific contributions to the binding interactions are not known; however, previous studies indicated that H69 conformational states are influenced by pH, and a more open structure of H69 is favored under more basic conditions. The phage selection against H69 was carried out at pH 7.5, suggesting that an open conformation with exposure of A1913 is favored for peptide binding.32, 37 Prior structure studies revealed that the H69 conformational states are important for ribosome activity such as subunit association.7 Thus, the ability to target one state versus another could be important for selective drug binding and activity.

The selected peptide showed preferential binding to the target H69 over other RNAs such as human H69 or helix 31 and the A site from 16S rRNA, suggesting that the peptide has unique features that give it specificity for modified bacterial H69. We are optimistic that these features, once understood more deeply through high-resolution structure determination or site-specific modification, will allow the peptide to be improved and developed into a lead compound for novel antimicrobials that target H9. Such experiments are currently in progress. Phage display provided a peptide that shares amino acid content with a known H69-binding protein, RRF, and binds to the target H69 RNA by exploiting both hydrophobic and polar amino acids. One limitation of phage display is that amplification of the selected phage requires E. coli. As a consequence, peptides that bind strongly to functional regions of the ribosome might not be amplified efficiently. Thus, peptides with strong affinity for H69 RNA might be lost because the E. coli host does not survive. Nonetheless, the peptide selected for H69 has comparable affinity to that of aminoglycoside antibiotics, which target the ribosome, and better selectivity than the known compounds. Furthermore, it is likely that the selected peptide can be improved through site-specific modifications and/or peptidomimetic chemistry. Therefore, the knowledge gained from such approaches will aid in designing effective peptide-based molecules against bacterial targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Cunningham and A. Saraiya for assistance with DNA sequencing, M. Li and B. Shay for ESI-MS training, J. Herath and Y.-C. Chang for m3Ψ amidite synthesis, S. Abeysirigunawardena for providing the H69 RNA variants, and M. Friedrich and K. Honn for providing access to the fluorescence microscope. This project is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM087596).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wright GD. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1451–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakulenko SB, Mobashery S. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:430–450. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.430-450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Baucom A, Lieberman K, Earnest TN, Cate JH, Noller HF. Science. 2001;292:883–896. doi: 10.1126/science.1060089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schuwirth BS, Borovinskaya MA, Hau CW, Zhang W, Vila-Sanjurjo A, Holton JM, Cate JH. Science. 2005;310:827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1117230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pai RD, Zhang W, Schuwirth BS, Hirokawa G, Kaji H, Kaji A, Cate JH. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1334–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Julián P, Milon P, Agirrezabala X, Lasso G, Gil D, Rodnina MV, Valle M. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Agrawal RK, Sharma MR, Kiel MC, Hirokawa G, Booth TM, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Kaji A, Frank J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8900–8905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401904101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Frank J, Agrawal RK. Nature. 2000;406:318–322. doi: 10.1038/35018597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Gabashvili IS, Agrawal RK, Spahn CM, Grassucci RA, Svergun DI, Frank J, Penczek P. Cell. 2000;100:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80690-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Gao H, Sengupta J, Valle M, Korostelev A, Eswar N, Stagg SM, Van Roey P, Agrawal RK, Harvey SC, Sali A, Chapman MS, Frank J. Cell. 2003;113:789–801. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bashan A, Yonath A. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:326–335. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell P, Osswald M, Brimacombe R. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3004–3011. doi: 10.1021/bi00126a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiväli U, Remme J. RNA. 2004;10:600–604. doi: 10.1261/rna.5220504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kipper K, Hetényi C, Sild S, Remme J, Liiv A. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:405–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson DN, Schluenzen F, Harms JM, Yoshida T, Ohkubo T, Albrecht R, Buerger J, Kobayashi Y, Fucini P. EMBO J. 2005;24:251–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Sakakibara Y, Chow CS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8396–8399. doi: 10.1021/ja2005658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Harms J, Schluenzen F, Zarivach R, Bashan A, Gat S, Agmon I, Bartels H, Franceschi F, Yonath A. Cell. 2001;107:679–688. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannone JJ, Subramanian S, Schnare MN, Collett JR, D’Souza LM, Du Y, Feng B, Lin N, Madabusi LV, Muller KM, Pande N, Shang Z, Yu N, Gutell RR. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sumita M, Jiang J, SantaLucia J, Jr, Chow CS. Biopolymers. 2012;97:94–106. doi: 10.1002/bip.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Kowalak JA, Bruenger E, Hashizume T, Peltier JM, Ofengand J, McCloskey JA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:688–693. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bakin A, Ofengand J. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9754–9762. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumita M, Desaulniers JP, Chang YC, Chui HM, Clos L, 2nd, Chow CS. RNA. 2005;11:1420–1429. doi: 10.1261/rna.2320605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ofengand J. FEBS Lett. 2002;514:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Borovinskaya MA, Pai RD, Zhang W, Schuwirth BS, Holton JM, Hirokawa G, Kaji H, Kaji A, Cate JH. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:727–732. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Scheunemann AE, Graham WD, Vendeix FA, Agris PF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3094–3105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bulkley D, Johnson F, Steitz TA. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith GP, Petrenko VA. Chem Rev. 1997;97:391–410. doi: 10.1021/cr960065d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Jamieson AC, Kim SH, Wells JA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5689–5685. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li M, Duc AC, Klosi E, Pattabiraman S, Spaller MR, Chow CS. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8299–8311. doi: 10.1021/bi900982t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lamichhane TN, Abeydeera ND, Duc AC, Cunningham PR, Chow CS. Molecules. 2011;16:1211–1239. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Eshete M, Marchbank MT, Deutscher SL, Sproat B, Leszczynska G, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. Protein J. 2007;26:61. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-9046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Llano-Sotelo B, Klepacki D, Mankin AS. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Sannes-Lowery KA, Hu P, Mack DP, Mei HY, Loo JA. Anal Chem. 1997;69:5130–5135. doi: 10.1021/ac970745w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sannes-Lowery KA, Mei HY, Loo JA. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1999;193:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chui HM, Desaulniers JP, Scaringe SA, Chow CS. J Org Chem. 2002;67:8847–8854. doi: 10.1021/jo026364m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atherton E, Sheppard RC. Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bligh SWA, Haley T, Lowe PN. J Mol Recognit. 2003;16:139–147. doi: 10.1002/jmr.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marvin DA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:150–158. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett RW, Cwirla SE, Ackerman MS, Olson AM, Peters EA, Dower WJ. Anal Biochem. 1992;204:357–364. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon MD, Sato K, Weiss GA, Shokat KM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3623–3631. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam KS, Lebl M. ImmunoMethods. 1992;1:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang S, Tamilarasu N, Ryan K, Huq I, Richter S, Still WC, Rana TM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman ER, Balighian ED, Mattoussi H, Kuno MK, Mauro JM, Tran PT, Anderson GP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6378–6382. doi: 10.1021/ja0125570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray CB, Norris DJ, Bawendi MG. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8706–8715. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim HK, Hsieh YL, Ganem B, Henion J. J Mass Spectrom. 1995;30:708–714. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z, Weber SG. Trends Analyt Chem. 2008;27:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meroueh M, Grohar PJ, Qiu J, SantaLucia J, Jr, Scaringe SA, Chow CS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2075–2083. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abeysirigunawardena SC, Chow CS. RNA. 2008;14:782–792. doi: 10.1261/rna.779908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Döring T, Mitchell P, Osswald M, Bochkariov D, Brimacombe R. EMBO J. 1994;13:2677–2685. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fourmy D, Recht MI, Blanchard SC, Puglisi JD. Science. 1996;274:1367–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaul M, Barbieri CM, Pilch DS. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sannes-Lowery KA, Griffey RH, Hofstadler SA. Anal Biochem. 2000;280:264–271. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desaulniers J-P, Chang Y-C, Aduri R, Abeysirigunawardena SC, SantaLucia J, Jr, Chow CS. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:3892–3895. doi: 10.1039/b812731j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.