Abstract

The objective of this study was to conduct the systematic evaluation of methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in Korea. The authors conducted a very comprehensive literature search to identify potential CPGs for evaluation. CPGs were selected which were consistent with a predetermined criteria. Four reviewers evaluated the quality of the CPGs using the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. AGREE item scores and standardized domain scores were calculated. The inter-rater reliability of each domain was evaluated using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). Consequently, 66 CPGs were selected and their quality evaluated. ICCs for CPG appraisal using the AGREE Instrument ranged from 0.626 to 0.877. Except for the "Scope and Purpose" and "Clarity and Presentation domains", 80% of CPGs scored less than 40 in all other domains. This review shows that many Korean research groups and academic societies have made considerable efforts to develop CPGs, and the number of CPGs has increased over time. However, the quality of CPGs in Korea were not good according to the AGREE Instrument evaluation. Therefore, we should make more of an effort to ensure the high quality of CPGs.

Keywords: Clinical Practice Guideline, Quality Improvement

INTRODUCTION

Greater attention has been placed on evidence-based medicine in recent years, and as a result, various methods are being used to manage clinical evidence. In particular, considerable efforts have been made to develop clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). CPGs are systematically developed statements that assist practitioners with decisions regarding the appropriate health care of patients under specific circumstances (1). CPGs may have many different objectives. In addition to providing training and information to the health care providers or users, they serve to control cost and volume of medical services (2).

Outside Korea, and particularly in western countries, considerable efforts are being made to develop CPGs. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia, and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), are among the many institutions establishing standards for new CPGs. Nevertheless, these standards do not guarantee the quality of CPGs (3). Subsequently, a group of researchers came together in the mid-1990s to promote the harmonized development and standardized evaluation of CPGs. They formed the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) Collaboration and developed the AGREE Instrument (4). The AGREE Instrument is intended to provide a framework for evaluating major elements of CPG quality, including development method and reporting of CPGs.

Many countries have adopted the AGREE Instrument to assess and validate the quality of CPGs, including CPGs for the management of particular diseases (5-8). It is also used to compare the quality of CPGs across countries (9) and for appraising the overall quality of CPGs developed within a country (10). In the case of Korea, translation work has been undertaken to facilitate the use of the AGREE Instrument (4), but no research has been done to assess the quality of all CPGs developed in Korea. This study aimed to assess the quality of CPGs in Korea using the AGREE Instrument.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To delve into the current state of Korea's clinical practice guidelines, we first identified CPGs according to the following inclusion criteria: 1) documents containing recommendations with the aim of guiding decisions between practitioners and patients on prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and management of diseases; 2) documents citing references that provide the basis for recommendations; 3) all documents published after 2004 were considered as CPGs; and 4) for guidelines that were developed based on a consensus among professional groups, only those that were developed using a formal consensus method (such as a Delphi technique) were considered as CPGs. Documents excluded from the category of professional CPGs were: 1) narrative reviews; 2) primary studies; 3) critical pathways; 4) text-like; 5) training manuals for medical professionals; 6) guidelines for patients; 7) technical guide for assessment and diagnosis; 8) documents on development methods; 9) documents explaining CPGs and how to use them; 10) government's health program guides for disease control; 11) translations of foreign guidelines; 12) guidelines or related documents developed by nursing, dental or oriental medicine societies; and 13) documents for which development methods could not be verified due to the original documents being unavailable.

Search for CPGs

The websites of academic societies engaged in CPG-related activities or other related organizations (i.e. the Korean Medical Guideline Information Center [KoMGI], the Korean Guideline Clearing House [KGC], the Health Insurance Review Agency [HIRA]) were reviewed to identify CPGs. In addition, we tried to gather information about the different CPGs available in Korea. Information specialists in the field of clinical medicine searched electronic documents. PubMed was searched as an international database, and KoreaMed, Medric (KMbase), Richis, NSDL (National Science Digital Library), National Assembly Library and KERIS Riss4u were searched as domestic databases. The search terms are shown in Table 1. Notes in academic conference papers and reports were also searched. The efforts to develop CPGs within clinical academic associations were also examined in parallel with a mail survey of 66 clinical academic associations which are not member societies of the Korean Academy of Medical Sciences (KAMS). All searched documents were reviewed by the chief researcher, and the original versions of the documents deemed to be relevant CPGs were obtained. Data were collected on the details such as development groups, financial source, development year, and revision status on each document identified as a CPG.

Table 1.

List of search terms

*For the National Assembly database, "practice" must be indicated for other searches to access this database.

The AGREE instrument

The AGREE Instrument (4) comprises 23 key items organized into six domains, each of which identifies a unique dimension in terms of practice guideline quality. Domain 1 (Scope and Purpose) includes items 1-3 and evaluates the clarity of the overall aim of the guideline, the specific health questions, and the target population described in the guideline. Domain 2 (Stakeholder Involvement) covers items 4-6 and examines the extent to which the guideline represents the views of its intended users, and domain 3 (Rigor of Development) is concerned with the process of gathering and synthesizing the evidence, the methods used to formulate the recommendations, and updating them (items 7-14). Domain 4 (Clarity and Presentation) comprises items 15-18 and focuses on the language and format of the guideline, whereas domain 5 (Applicability, items 19-21) deals with the organizations likely to use the guideline and the costs of applying the guideline. Domain 6 (Editorial Independence) pertains to the independence of the recommendations and any possible conflicts of interest within the guideline development group (items 22-23). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale: "Strongly Agree (4)", "Agree (3)", "Disagree (2)", and "Strongly Disagree (1)". The higher the score, the higher the quality of each item.

Evaluation of CPGs

To evaluate the CPGs effectively and to strengthen consistency during appraisal, four members of our research team participated in the appraisal panel. Each member contributed his/her knowledge of developing and evaluating CPGs by attending a seminar prior to evaluating the CPGs. A CPG appraisal workshop was conducted so that several CPGs could be appraised in pilot runs. Each appraiser individually appraised CPGs and reviewed the results. Appraisers were given opportunities to hear each other's views on the appraisal results. These discussions were conducted freely, as there was no desire to unify the results.

Analysis

Mean item scores and standardized domain scores for each CPG were calculated by averaging the scores across the four reviewers. Standardized domain scores were calculated as follows:

Standardized scores for each domain according to developing organization, financial source, development year, and revision status were compared using the t-test. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for each domain of the AGREE Instrument using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). We used SPSS for Windows 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was exempted from approval by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2012-0489).

RESULTS

Selection of CPGs

The CPG selection process is presented in Fig. 1. By using various methods to examine the development of CPGs in Korea, we identified 713 documents as potential CPGs. Forty-six were obtained from CPG-related websites, three were identified through note searches, and 647 were identified from database searches. The survey of clinical academic associations gained responses from 43/63 academic societies (a 68.3% response rate), and 17 CPGs from eight academic societies were identified.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing selection of clinical practice guidelines.

The chief researcher reviewed the abstracts or documents and identified 276 documents as potential CPGs. The exclusion criteria eliminated 203 of these. Of the remaining potential documents, three were excluded by 4 reviewers since they were focused primarily on epidemiology and pathophysiology and their recommendations were obscure. Four other documents were actual CPGs, but were excluded from the review as the full document was not available. Sixty-six remaining documents were selected for inclusion in the study.

Finally 66 guidelines were selected for evaluation and several guidelines were published as an academic paper such as practice parameters for pervasive developmental disorder, management of chronic hepatitis B, guideline for chronic renal disease and diagnostic guideline of ulcerative colitis (11-14).

When we examined the developing organization responsible for the 66 selected CPGs, we found that 47 (71.2%) CPGs were developed by academic organizations (i.e. academic societies). In terms of funding, 34 (51.5%) CPGs were supported by Republic of Korea Government and 5 (7.6%) were funded by the academic societies themselves (there were also cases in which private companies provided funding). However, the funding source could not be identified in 26 cases. We also observed an increasing trend in the number of CPGs developed over the years. Fifty-four (81.8%) of the CPGs reviewed were first editions and 12 (18.2%) were revised (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of clinical practice guidelines reviewed in this study

Guideline appraisal results

The majority of the 66 CPGs appraised using the AGREE Instrument obtained very low scores. Except for the "Scope and Purpose" and "Clarity and Presentation" domains, 80% of CPGs scored less than 40. In particular, the median score in the "Applicability" domain was zero and that in the "Editorial Independence" domain was 4.2, indicating extremely low quality in these areas. The variability in the domain scores was quite wide, ranging from 45.8 to 88.9 (Fig. 2). Fifteen out of 23 AGREE items received a score of less than 2. Items in the "Clarity and Presentation" domain (except item 18), obtained relatively good values (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of standardized domain scores for 66 clinical practice guidelines. The top and bottom of the box represents the 75th (Q3) and 25th percentile (Q1), respectively, and the band near the middle of the box indicates the 50th percentile (the median). The upper and lower ends of the whisker represent Q3 + 1.5 × (interquartile range), and Q1-1.5 × (interquartile range), respectively. Small dot (○) represents outlier values which lies more than 1.5 times to 3.0 times interquartile range from either end of the whisker. Asterisk (*) represents extreme outlier values which lies more than 3 times interquartile range from either end of the whisker.

Table 3.

Standardized AGREE domain scores according to clinical practice guideline characteristics

*P < 0.05.

Comparison of the standardized AGREE domain scores according to CPG characteristics showed that the numbers were generally stable before and after 2006, but newer CPGs received higher scores than older ones in the "Scope and Purpose" domain. This result was statistically significant (P = 0.004). CPGs that received governmental support scored lower (P = 0.007) in the "Stakeholder Involvement" domain, but scored higher in the "Applicability domain", than those that were funded by other sources; however, all scores were fairly low. In terms of the developing organization, CPGs developed by research groups or by academic societies obtained significantly higher scores in the "Scope and Purpose" and "Editorial Independence" domains. In terms of revisions, first editions scored significantly higher in the "Stakeholder Involvement" domain. The magnitude of the domain scores according to CPG characteristics varied according to the domain, and the differences between the scores were not statistically significant in most cases (Table 4).

Table 4.

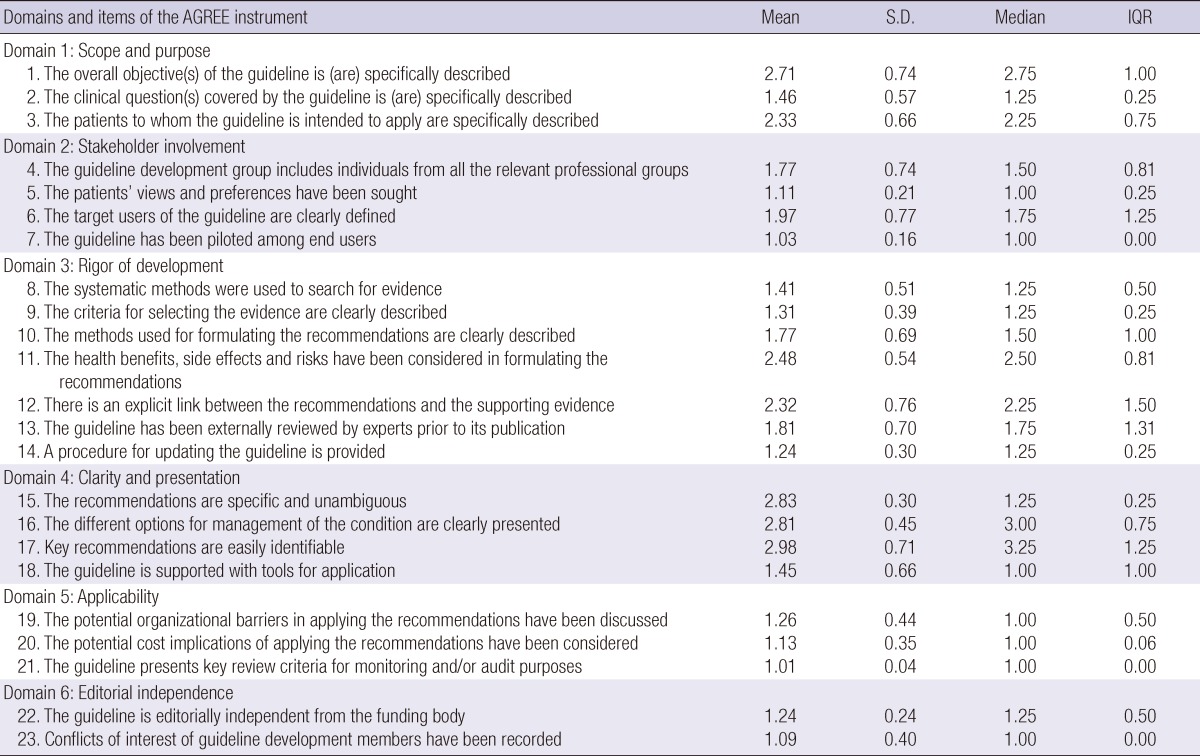

AGREE item scores

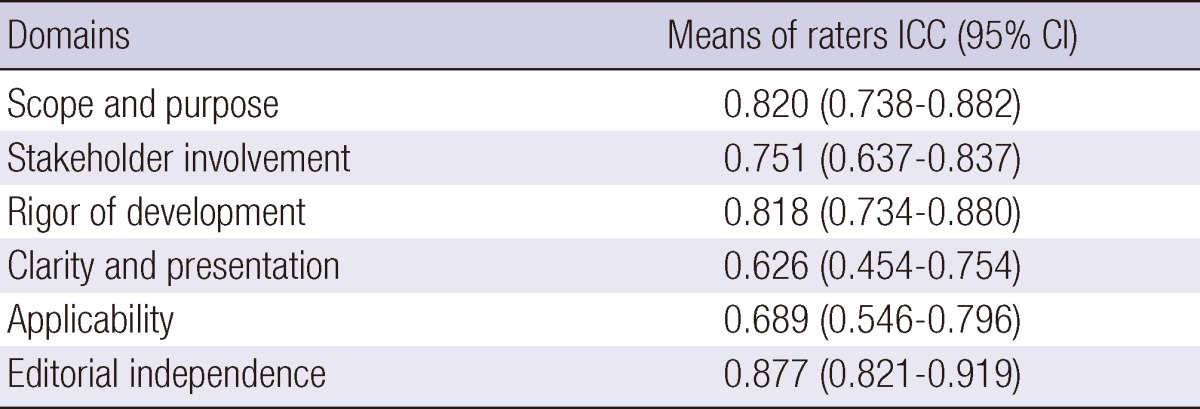

Reliability measures of CPG appraisal using the AGREE Instrument showed high scores in general. The ICCs for AGREE appraisal conducted by the four raters were lowest in the "Clarity" domain (0.626), but higher in the "Scope and Purpose", "Rigor of Development" and "Editorial Independence" domains (all > 0.8) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Intra-class correlation coefficient for mean rater scores by AGREE domain

DISCUSSION

This was the first study to do systematic investigation of the methodological quality of CPGs in Korea. The important findings of this evaluation was that across different clinical areas, academic organizations and research groups have put a considerable amount of effort into developing CPGs, and the number of CPGs has increased every year. However, the overall quality of the CPGs was not good, particularly in the domains of "Applicability" and "Editorial independence"

A total of 66 CPGs was selected from 713 documents identified through the comprehensive search. We can assume that the CPGs not identified in this study have little potential for use in practice. The CPGs evaluated in this report were primarily retrieved from CPGs deposited in the KoMGI database and the KGC. Search results from professional and general websites were added subsequently. Also, to cover CPGs developed by academic societies and research groups, the CPGs identified from surveys returned by academic societies in medical and healthcare fields (excluding those that are subsidiaries of the KAMS). Previous studies also excluded CPGs not identified in professional databases or by internet searches using appropriate search terms (10, 15).

The present study also shows that the quality of CPGs can be reliably evaluated using the AGREE Instrument as other studies applied the AGREE Instrument for CPG quality evaluation showed high reliability (10, 16, 17). We involved four experts with experience in developing or evaluating CPGs. In addition, the seminar and workshop conducted before the appraisals help to improve the general understanding of the AGREE Instrument items and also to achieve good reliability.

AGREE is an instrument used to evaluate the quality of CPGs by appraising development methods and related characteristics, among others (4). It focuses on how effectively the quality has been maintained throughout the CPG development process, clarity of purpose and scope, the involvement of stakeholders in the developmental process, the organization of the searches, and the selection methods used. AGREE does not assess the clinical content of CPGs. Therefore, a low score awarded to a particular CPG by the AGREE Instrument does not necessarily directly imply the low value of clinical contents. However, for CPGs that do not at least specify the use of logical methods, it is difficult for readers to assess suitability based on content alone. Thus, to develop high quality CPGs, the development process should at least be conducted in a systematic manner. This study did not identify an improvement in the quality of the CPGs over time, except in the "Scope and Purpose" domain. Some previous reports show that the various domains scores improved over time (6, 16, 18), whereas other did not (8, 15). However, considering cases in western countries such as UK which have systematic manuals for CPGs the quality of these processes could be improved if the appropriate methodology for CPG development is disseminated.

Compared with recent studies on CPGs developed in many developed countries based on the AGREE Instrument, the present study found that the quality of the CPGs developed in Korea was very low (5-9, 15-20). In particular, the quality of Korean CPGs was lower than those from other countries in terms of the "Applicability" and "Editorial Independence" domains, as reflected by the low absolute scores. Although most studies report relatively low scores in these two domains (6, 7, 10, 16, 18, 19-23), few report a score below 20 (10, 18, 22). For 13 out of 23 items, more than 80% were appraised as "Disagree" or "Strongly Disagree" in the present study. There were several cases in which the appraisal score was low because requirements of the items were met but were not specified in the CPG (i.e. 'the guideline development group includes individuals from all the relevant professional groups'). Yet in most cases, a lack of awareness of each item appeared to be a problem, as suggested in the comments section by the raters. From a technical perspective, the following problems were raised: virtually none of the CPGs specified the development process separately, and the developing entity, source of funding, and ethical issues were hardly discussed. However, in some domains, especially "Scope and Purpose", the scores improved over time. Zhang et al. reported that the quality of CPGs could be improved over time (6). Therefore, if CPG development groups appreciate the importance of scientific methodology, and understand how to achieve it, the quality of CPGs should improve further.

This study has a number of limitations. For instance, despite the various methods used to investigate CPGs, there was some difficulty in obtaining some original documents, which meant that some of the CPGs from the final pool were not appraised. However, most of the original documents were retrieved, so this should not greatly affect the overall appraisal results for Korea's CPGs. Additionally, while the AGREE Instrument is an appropriate tool for evaluating a near-complete spectrum of CPGs, including newly developed, existing or updated ones, it is difficult to comprehensively evaluate CPGs that adaptation method have been applied. Thus, we may need an alternative approach to evaluate CPGs that went through adaptation. Moreover, limitations exist within the AGREE Instrument itself; low scores are inevitable if not specified in the CPGs, even when the requirements are met, since the appraisal is based on the content described in the CPGs. In addition, the AGREE II Instrument has recently been developed and used to evaluate the quality of CPGs (24, 25). Researchers will therefore need to consider the new version of the AGREE Instrument in future. Despite these limitations, this study is useful because it is the first to assess the current CPGs available in Korea, and evaluates the quality of their development process.

Based on this study of CPG development in Korea, we can see that a considerable amount of effort has been put into their development. However, the overall quality was not good through the appraisal process using the AGREE Instrument. To develop high quality CPGs, effective strategies should be established to improve clarification of the subject of CPGs, the application of evidence-based systematic methods, and to deal with ethical issues. In particular, quality appraisals should be conducted, starting with the CPGs funded by the government, and continuous efforts should be undertaken to enhance the overall quality of CPGs in Korea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We deeply thank for Dr. SM Jee who supported collection and organization of clinical practice guidelines. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix 1

Lists of Clinical Practice Guidelines*

*If there was no English subject, researchers arbitrarily translated Korean into English.

Footnotes

This study was done by financial support of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) in the Ministry of Public Health and Social Welfare (2008-E-33038-00, 2008).

References

- 1.Field MJ, Lohr KN. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauly MV, Eisenberg JM, Radany MH, Erder MH, Feldman R, Schwartz JS. Paying physicians: options for controlling cost, volume, and intensity of services. Ann Arbor: Health Administration Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgers JS, Grol R, Klazinga NS, Mäkelä M, Zaat J AGREE Collaboration. Towards evidence-based clinical practice: an international survey of 18 clinical guideline programs. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:31–45. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/15.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AGREE Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagy E, Watine J, Bunting PS, Onody R, Oosterhuis WP, Rogic D, Sandberg S, Boda K, Horvath AR IFCC Task Force on the Global Campaign for Diabetes Mellitus. Do guidelines for the diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes mellitus fulfill the criteria of evidence-based guideline development? Clin Chem. 2008;54:1872–1882. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.109082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:981–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wijkstra J, Schubart CD, Nolen WA. Treatment of unipolar psychotic depression: the use of evidence in practice guidelines. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10:409–415. doi: 10.1080/15622970701599052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurdowar A, Graham ID, Bayley M, Harrison M, Wood-Dauphinee S, Bhogal S. Quality of stroke rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Wees PJ, Hendriks EJ, Custers JW, Burgers JS, Dekker J, de Bie RA. Comparison of international guideline programs to evaluate and update the Dutch program for clinical guideline development in physical therapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:191. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esandi ME, Ortiz Z, Chapman E, Dieguez MG, Mejía R, Bernztein R. Production and quality of clinical practice guidelines in Argentina (1994-2004): a cross-sectional study. Implement Sci. 2008;3:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho IH, Yoo HK, Son JW, Yoo HJ, Koo YJ, Chung US, Ahn DH, Ahn JS. The Korean practice parameter for the treatment of pervasive developmental disorders: pharmacological treatment. J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;18:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KS, Kim DJ Guideline Committee of the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. Management for chronic hepatitis B. Korean J Hepatol. 2007;13:447–488. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2007.13.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Korean Society of Nephrology. Clinical practice guideline for chronic renal disease. Korean J Nephrol. 2009;28:S1–S98. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi CH, Jung SA, Lee BI, Lee KM, Kim JS, Han DS IBD Study Group of the Korean Association of the Study of Intestinal Diseases. Diagnostic guideline of ulcerative colitis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:145–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Haugh MC, Brouwers M, Browman G, Cluzeau F, Philip T. Predictors of high quality clinical practice guidelines: examples in oncology. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:123–132. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, Gich I, Delgado-Noguera M, Rigau D, Tort S, Bonfill X, Burgers J, Schunemann H. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDermid JC, Brooks D, Solway S, Switzer-McIntyre S, Brosseau L, Graham ID. Reliability and validity of the AGREE instrument used by physical therapists in assessment of clinical practice guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimbo T, Fukui T, Ishioka C, Okamoto K, Okamoto T, Kameoka S, Sato A, Toi M, Matsui K, Mayumi T, et al. Quality of guideline development assessed by the Evaluation Committee of the Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0060-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nast A, Spuls PH, Ormerod AD, Reytan N, Saiag PH, Smith CH, Rzany B. A critical appraisal of evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: 'AGREE-ing' on a common base for European evidence-based psoriasis treatment guidelines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:782–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wennekes L, Hermens RP, van Heumen K, Runde V, Schoelen H, Wollersheim HC, Grol RP, de Mulder PH, Ottevanger PB. Possibilities for transborder cooperation in breast cancer care in Europe: a comparative analysis regarding the content, quality and evidence use of breast cancer guidelines. Breast. 2008;17:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone MA, Wilkinson JC, Charpentier G, Clochard N, Grassi G, Lindblad U, Müller UA, Nolan J, Rutten GE, Khunti K. Evaluation and comparison of guidelines for the management of people with type 2 diabetes from eight European countries. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinnunen-Amoroso M, Pasternack I, Mattila S, Parantainen A. Evaluation of the practice guidelines of Finnish Institute of Occupational Health with AGREE instrument. Ind Health. 2009;47:689–693. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.47.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan JK, Wolfe BJ, Bulatovic R, Jones EB, Lo AY. Critical appraisal of quality of clinical practice guidelines for treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, 2006-2009. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2389–2395. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferket BS, Genders TS, Colkesen EB, Visser JJ, Spronk S, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG. Systematic review of guidelines on imaging of asymptomatic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1591–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]